Towards Heritage Community Assessment: Indicators Proposal for the Self-Evaluation in Faro Convention Network Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

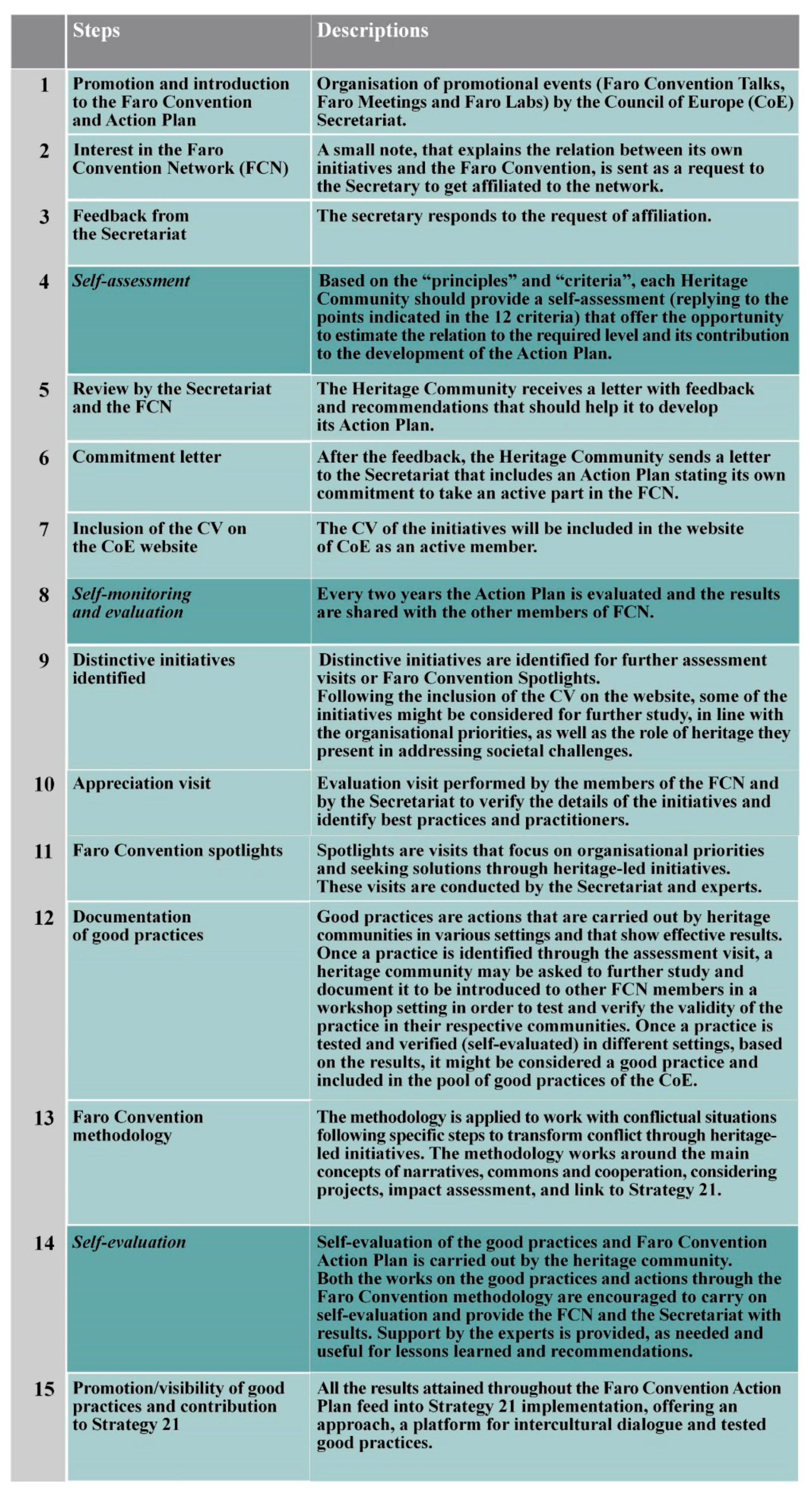

2.1. The Faro Process

- 1.

- connection to a community and territory determines a sense of belonging;

- 2.

- social cohesion is founded on various levels of cooperation and commitment;

- 3.

- democracy is practised by the engagement of civil society in dialogue and action, through shared responsibilities based on capacities.

2.2. Evaluation Tools for Heritage Community: Indicators Proposal for the Self-Assessment

3. Results

3.1. The Case Study: Friends of Molo San Vincenzo

3.2. The Heritage Community of Friends of Molo San Vincenzo: Testing the Methodology

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- The first aspect underlines that the term “cultural commons” can combine the concepts of cultural heritage and the common good, expression of the interplay relationship between the culture of communities and their shared values.

- The second aspect, complementary to the first one, highlights the concept of “heritage community” [51]) and its definition, developed by the Faro Convention and interpreted as a group of persons that recognise the value of the cultural heritage and that aims to support it and transmit it to future generations. The heritage community is formed during the process of involvement and enhancement of cultural heritage. It is the result of a process of sharing values and experiences, which contributes to generating the bonds that structure a community.

- The Faro Convention is an important reference as it provides principles, criteria, and tools (the affiliation process with the self-management grid and the Faro action plan) and is the support to the heritage communities (Faro Convention Network), leaving them free to define and experiment new patterns of urban regeneration.

- The in-depth analysis of the Faro Convention tools has revealed the necessity to structure the evaluation of these processes based on clearly defined indicators to compare the different experiences, and to understand and to interpret the progressive results.

- The hypothesis of the indicators seems promising to guarantee the required objectivity. However, the process has been built as a learning tool and as a platform for dialogue. Therefore, defining precise options could reduce its learning value.

- The self-evaluation process is relevant to redefine and redesign the relations between actors working on the heritage and between those who are involved in its governance.

- The tool of the self-management process is, therefore, of fundamental importance, since it supports the ex-ante and ex-post phases of the evaluation. It is also a potent tool through which the community may reflect on the project, sharing the results with other stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bandarin, F. World Heritage—Challenges for the Millenium, 1st ed.; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, L. Ereditare Il Futuro: Dilemmi Sul Patrimonio Culturale; Il Mulino: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Parowicz, I. Cultural Heritage Marketing: A Relationship Marketing Approach to Conservation Services; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bleibleh, S.; Awad, J. Preserving cultural heritage: Shifting paradigms in the face of war, occupation, and identity. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 44, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorkildsen, A.; Ekman, M. The complexity of becoming: Collaborative planning and cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 3, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borona, G.; Ndiema, E. Merging research, conservation and community en-gagement: Perspectives from TARA’s rock art community projects in Kenya. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K. Introduction. Capturing the Public Value of Heritage. In Proceedings of the London Conference, London, UK, 25–26 January 2006; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; The Belknap Press of Harward University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D.; Robert, L.; Raffaella, N. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, G.L.; Peter, N. Le Valutazioni per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile della Città e del Territorio, 3rd ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.; Ferilli, G.; Blessi, G.T. Understanding culture-led local development: A critique of alternative theoretical explanations. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2806–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roders, A.P.; Oers, R. Van Editorial: Bridging cultural heritage and sustainable development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe (CoE). Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. In Faro Declaration of the Council of Europe’s Strategy for Developing Intercultural Dialogue; 2005; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- European Commission (EC). Council Conclusions on Participatory Governance of Cultural Heritage. 2018. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52014XG1223(01)&from=EN (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo (MiBAC). Innovazione e Tecnologia: Le Nuove Frontiere Del MiBAC Direzione Generale per La Valorizzazione Del Patrimonio Culturale; MiBAC: Rome, Italy, 2009.

- Council of Europe. Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the European Cultural Heritage Strategy for the 21st Century. 2017. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806f6a03 (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Montella, M. La Convenzione Di Faro e La Tradizione Culturale Italiana. In Il Capitale Culturale: Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage; Available online: http://riviste.unimc.it/index.php/cap-cult/article/view/1567/1072 (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Bieczyński, M. The ‘Right to Cultural Heritage’ in the European Union: A Tale of Two Courts. In Cultural Heritage in the European Union; Jakubowski, A., Hausler, K., Fiorentini, F., Eds.; Brill Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 9, pp. 113–140. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). A New European Agenda for Culture-SWD (2018) 267 Final. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/culture/document/new-european-agenda-culture-swd2018-267-final (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Zhang, Y. Heritage as Cultural Commons: Towards an Institutional Approach of Self-Governance. In Cultural Commons A New Perspective on the Production and Evolution of Cultures; Enrico, B., Giangiacomo, B., Massimo, M., Walter, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; Volume 259. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, P.A. From a Given to a Construct. Cult. Stud. 2014, 28, 359–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 0521405998. [Google Scholar]

- Settis, S. Azione Popolare: Cittadini per Il Bene Comune; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bollier, D.; Parrella, B. La Rinascita dei Commons; Stampa Alternativa: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, C.; Rheingold, H.; Nannery, R.S.; Kashwan, P.; Mcginnis, M.; Cole, D.; Walker, J.; Anh, L.; Long, N.; Arnold, G.; et al. Mapping the New Commons. Syracuse Univ. Surf. 2008, 6, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccoli, L. Commons/Beni Comuni. Il Dibattito Internazionale; GoWare: Florence, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bertacchini, E.; Bravo, G.; Marrelli, M.; Santagata, W. Defining Cultural Commons. In Cultural Commons A New Perspective on the Production and Evolution of Cultures; Bertacchini, E., Bravo, G., Marrelli, M., Santagata, W., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Chelteman, UK, 2012; p. 259. [Google Scholar]

- Mattei, U. Patrimonio Culturale e Beni Comuni: Un Nuovo Compito per La Comunità Internazionale. In Protecting Cultural Heritage as a Common Good of Humanity: A Challenge for Criminal Justice; Stfefano, M., Arianna, V., Eds.; 2015; Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/congress/background-information/Transnational_Organized_Crime/ISPAC_Protecting_Cultural_Heritage_2014.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Navrud, S.; Ready, R.C. Valuing Cultural Heritage: Ap- plying Environmental Valuation Techniques to Historic Buildings, Monuments and Artifacts. J. Cult. Econ. 2003, 27, 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- Clarck, K. Forward Planning: The Function of Cultural Heritage in Changing Europe—Experts’ Contributions; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2001; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, A. Beni Comuni, Patrimonio Culturale e Turismo. Introduzione; Società di Studi Geografici: Florence, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-88-908926-2-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zagato, L. The Notion of “Heritage Community” in the Council of Europe’s Faro Convention. Its Impact on the European Legal Framework. 2015. Available online: https://books.openedition.org/gup/220 (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). General Comment Number 21, on the Right to Participate in Cultural Life. 2009. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ed35bae2.html (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Ostrom, E.; Roy, G.; James, W. Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning in Perspective. Plan. Theory 2003, 2, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forester, J. Planning in the Face of Conflict: The Surprising Possibilities of Facilitative Leadership; American Planning Association Planners Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin, J. The Zero Marginal Cost Society; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ciolfi, L.; Areti, D.; Eva, H.; Monika, L.; Laura, M. Introduction. In Cultural Heritage Communities: Technologies and Challenges; Luigina, C., Areti, D., Eva, H., Monika, L., Laura, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, M.; Caterina, A.; Eleonora, G.d.G.; Fortuna, P. Trans-Disciplinary Approach to Maritime-Urban Regeneration in the Case Study ‘Friends of Molo San Vincenzo’, Port of Naples, Italy. In Proceedings of the Joint Conference Citta 8th Annual Conference on Planning Research Aesop Tg/Public Spaces & Urban Cultures Meeting Generative Places, Smart Approaches, Happy People, Porto, Portugal, 24–25 September 2015; pp. 701–718. [Google Scholar]

- Cass, N. Participatory-Deliberative Engagement: A Literature Review; Manchester University: Manchester, UK, 2006; Available online: http://geography.exeter.ac.uk/beyond_nimbyism/deliverables/bn_wp1_2.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Cerreta, M. Thinking Through Complex Values. In Making Strategies in Spatial Planning. Urban and Landscape Perspectives; Cerreta, M., Concilio, G., Monno, V., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 9, pp. 381–404. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Panaro, S. From Perceived Values to Shared Values: A Multi-Stakeholder Spatial Decision Analysis (M-SSDA) for Resilient Landscapes. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Daldanise, G.; Sposito, S. Culture-led regeneration for urban spaces: Monitoring complex values networks in action. Urbani Izziv 2018, 29, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamagni, S.; Vera, Z. La Cooperazione; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.L.; Guido, F.; Giorgio, T.B. Cultura e Sviluppo Locale. Verso il Distretto Culturale Evoluto; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. FCN Principles and Criteria. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/fcn-principles-and-criteria (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- Council of Europe. Faro Convention Network (FCN). Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-community#portlet_56_INSTANCE_5mjl2VH0zeQr (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- Council of Europe. Steering Committee for Culture, Heritage and Landscape (CDCPP) Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society the Faro Action Plan 2016–2017. 2016. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=09000016806abda0 (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Council of Europe Steering Committee for Culture, Heritage and Landscape. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806a487d (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- Friends of Molo San Vincenzo. 2018. Available online: https://friendsofmolosanvincenzo.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- De Nito, E.; Andrea, T.; Alessandro, H.; Gianluigi, M. Collaborative Governance: A Successful Case of Pubblic and Private Interaction in the Port City of Naples. In Hybridity and Cross-Sectoral Relations in the Delivery of Public Services; Andrea, S., Luca, G., Alessandro, H., Fabio, M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Graeme, E.; Phyllida, S. A Review of Evidence on the Role of Culture in Regeneration; Department for Culture Media and Sport: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Knowledge for Action; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, D.J.; Davison, R.; Martinsons, M.G.; Kock, N. Teaching/learning action research requires fundamental reforms in public higher education. Inf. Syst. J. 2004, 14, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, D.J.; Levin, M. Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 9781412925976. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, M.; Eleonora, G.d.G. Friends of Molo San Vincenzo: Heritage Community per il recupero del Molo borbonico nel porto di Napoli. In Il Valore del Patrimonio Culturale per la Società e le Comunità, la Convenzione del Consiglio d’Europa tra Teoria e Prassi; Luisella, P.W., Simona, P., Eds.; CoE Venezia, Linea Edizioni: Venezia, Italy, 2019; pp. 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Heritage Walk. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/venice/heritage-walk (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- Giovene di Girasole, E. Passeggiata Patrimoniale al Bacino di Raddobbo Borbonico e Molo San Vincenzo—Friends of Molo San Vincenzo. Available online: https://friendsofmolosanvincenzo.wordpress.com/2017/10/13/passeggiata-patrimoniale-al-bacino-di-raddobbo-borbonico-e-molo-san-vincenzo/ (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- Hess, C. Constructing a New Research Agenda for Cultural Commons. In Cultural Commons: A New Perspective on the Production and Evolution of Cultures; Bertacchini, E., Bravo, G., Marrelli, M., Santagata, W., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; p. 259. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Poli, G. Landscape Services Assessment: A Hybrid Multi-Criteria Spatial Decision Support System (MC-SDSS). Sustainability 2017, 9, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Timmeren, A.; Henriquez, L.; Reynolds, A. Ubikquity & the illuminated city. In Illuminated City. From Smart to Intelligent Urban Environments, 1st ed.; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria: “Who?” | |

|---|---|

| Indicators | Value |

| 1. Presence of an active civil society (heritage community) that has a common interest in a specific heritage. A heritage community consists of people who value specific aspects of cultural heritage which they wish, within the framework of public action, to sustain and transmit to future generations. | |

| No presence | 1 |

| Presence from 1 to 5 persons | 2 |

| Presence of more persons and stakeholders (entrepreneurs, associations, etc.) or academics | 3 |

| Constitution of an association with a formal process that include these actors | 4 |

| Affiliation to the Faro Convention Network | 5 |

| 2. Presence of people who can convey the message (facilitators) | |

| No presence | 1 |

| 1 facilitator | 2 |

| More facilitators | 3 |

| Presence of a multidisciplinary group of facilitators that take care of the regeneration of the specific cultural heritage | 4 |

| Presence of a group of facilitators that is formally responsible for the regeneration of the specific cultural heritage | 5 |

| 3. Engaged and supportive political players in the public sector (local, regional, national institutes, and authorities) | |

| No presence | 1 |

| Only 1 of these political players: local, regional, national institutes, and authorities | 2 |

| Only 2 of these political players: local, regional, national institutes, and authorities | 3 |

| Only 3 of these political players: local, regional, national institutes, and authorities | 4 |

| All of these political players: local, regional, national institutes, and authorities, and subscription to a protocol agreement/memorandum of understanding for the regeneration | 5 |

| Note: political players must be actively involved (e.g., municipality, region, local state authority, holding institutions (national or regional level), CoE, etc.). | |

| 4. Engaged and supportive stakeholders in the private sector (businesses, non-profit entities, academia, CSOs, NGOs, etc.) | |

| No presence | 1 |

| Only 1 of these stakeholders: businesses, non-profit entities, academia, CSOs, and NGOs | 2 |

| Only 2 of these stakeholders: businesses, non-profit entities, academia, CSOs, and NGOs | 3 |

| Only 3 of these stakeholders: businesses, non-profit entities, academia, CSOs, and NGOs | 4 |

| Subscription to a memorandum of understanding for the regeneration between businesses, non-profit entities, academia, CSOs, and NGOs | 5 |

| Note: private stakeholders must be actively engaged. | |

| Values | Semantic Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 | No action |

| 2 | Realisation of and/or participation in events, meetings, initiatives, etc. |

| 3 | Signing of memorandum of understanding, manifestos, etc., on a shared vision for action |

| 4 | Approval of shared projects and/or action of enhancement |

| 5 | Realisation of shared projects and/or actions of enhancement |

| Criteria: “How?” | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5. Consensus on an expanded common vision of heritage | |||

| Semantic definition | HC | PI | PS |

| No consensus | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Participation in events to clarify the different visions on the CH | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Signing of memorandum of understanding on common heritage visions | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Approval of projects or actions of shared regeneration of the CH | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Implementation of actions or shared projects | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 6. Willingness of all stakeholders to cooperate (local authorities and civil society) | |||

| Semantic definition | HC | PI | PS |

| No cooperation | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cooperation limited to the realisation of joint events | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Signing of memorandum of understanding, manifestos, etc.. | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Cooperation to define projects or actions of shared regeneration of the CH | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Cooperation to implement the project or actions of regeneration of the CH | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 7. A defined common interest of a heritage-led action | |||

| Semantic definition | HC | PI | PS |

| No interest | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Participation in events to present the different visions on heritage-led development actions | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Signing of memorandum of understanding, manifestos on a common vision on heritage-led development actions | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Participation in the definition of actions, policies, or projects of heritage-led regeneration actions | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Implementation of actions, policies, or projects of heritage-led regeneration actions | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 8. Commitment and capacity for resource mobilisation | |||

| Semantic definition | HC | PI | PS |

| No engagement or capability | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No engagement or capability | No engagement or capability | No engagement or capability | |

| Provision of funds, knowledge, experience and skills | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Volunteering for events and exhibitions | Economic or logistical support for events and exhibitions | Economic support, knowledge, experience and skills for events and exhibitions | |

| Definition of or participation in fundraising for conservation of the CH | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Initiation of crowdfunding initiatives for the conservation of the CH | Tax reduction, (lottery for monuments, Sisal betting) or similar for the conservation of the CH | Economic support, knowledge, experience and skills for the conservation of the CH | |

| Definition of and participation in funds for actions and projects of CH regeneration | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Initiation of crowdfunding initiatives for the regeneration of the CH | Granting of long-term funding for regeneration actions and projects | Economic support/knowledge, experience and skills for regeneration actions and projects | |

| Development of a common strategy to mobilise resources for heritage regeneration experience and skills | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Involvement of experts with significant experiences and different skills | Involvement of experts with significant experiences and different skills | Involvement of experts with significant experiences and different skills | |

| Cultural Heritage [CH]; Heritage Community [HC]; Public Institution [PI}; Private Sector [PS] | |||

| Criteria: “What?” | |||

|---|---|---|---|

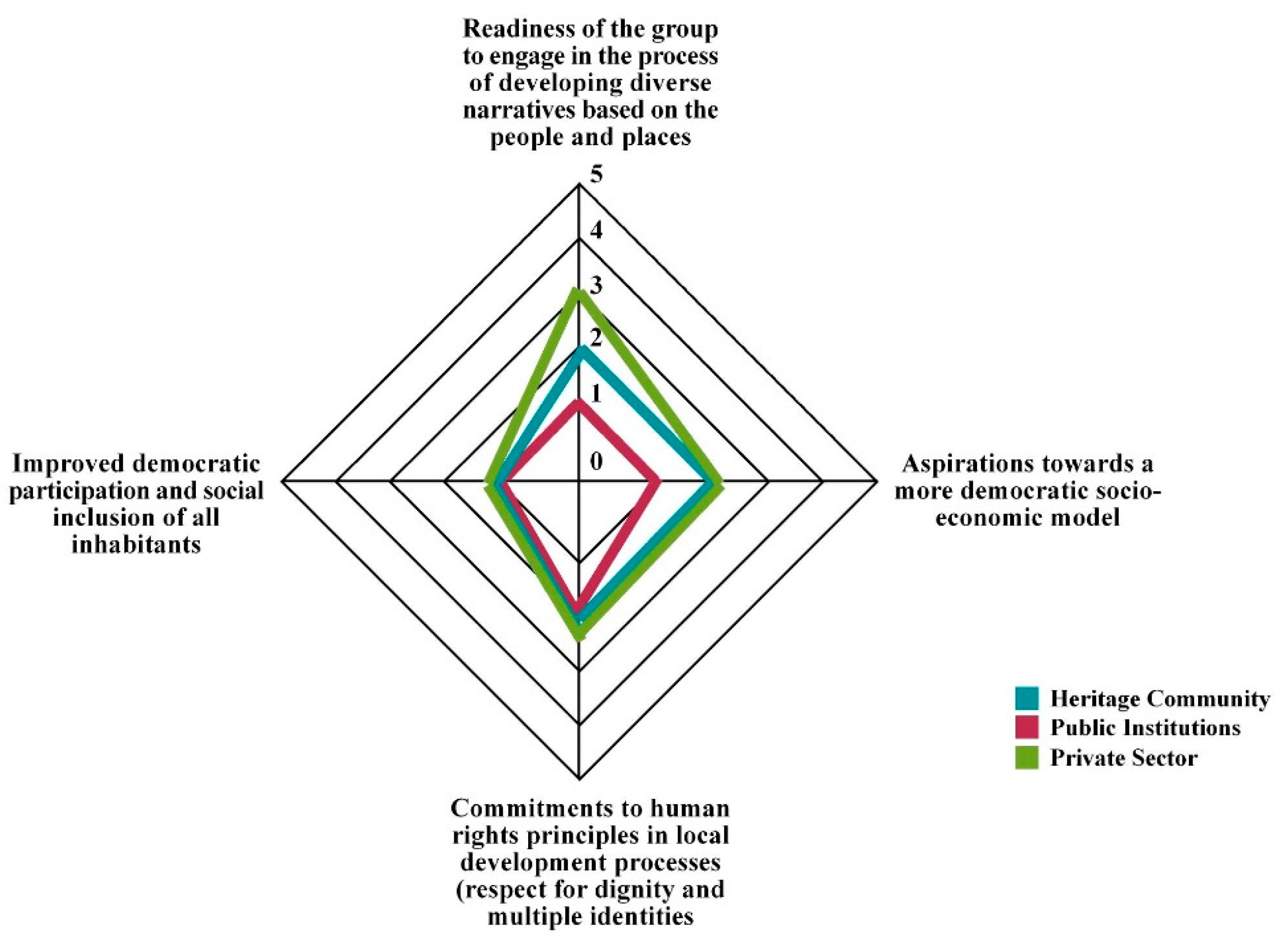

| 9. Readiness of the group to engage in the process of developing diverse narratives based on the people and places | |||

| Semantic definition | HC | PI | PS |

| No involvement | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Organisation of events to present diverse narratives based on the people and places | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Definition of reports, research, etc. to clarify the diverse narratives based on the people and places and identify the shared vision | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Approval of shared regeneration projects (action projects) based on shared vision and narratives based on the people and places | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Implementation of shared regeneration projects (action projects), based on the shared vision and narratives based on the people and places | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 10. Aspirations towards a more democratic socio-economic model | |||

| Semantic definition | HC | PI | PS |

| No aspiration | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Participation in meetings aimed at increasing inclusion and participation in the relevant choices | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Definition of protocols articulating the requests expressed by the whole community and the sustainable economic models | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Definition of projects that respect the requests expressed by the whole community and the sustainable economic models | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Implementation of projects that respect the requests expressed by the whole community and the sustainable economic models | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 11. Commitment to human rights principles in local development processes (respect for dignity and multiple identities) | |||

| Semantic definition | HC | PI | PS |

| No action | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Organisation of, or participation in, events to develop knowledge of the cultural heritage of all cultural communities | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Definition of memorandum of understanding, manifestos, etc., that consider all the relevant knowledge and viewpoints | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Definition of shared projects that include all the knowledge and viewpoints represented. | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Implementation of shared projects that include all the knowledge and viewpoints represented. | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 12. Improved democratic participation and social inclusion of all inhabitants | |||

| Semantic definition | HC | PI | PS |

| No action | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Organisation of, or participation in, campaigns, events, or actions for the involvement of all inhabitants | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Definition of memorandum of understanding, manifestos, etc., that express the shared vision for action built on the social inclusion of all inhabitants | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Definition of projects that express the shared vision for action built on the social inclusion of all inhabitants | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Implementation of regeneration projects that express the shared vision for action built on the social inclusion of all inhabitants | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Heritage Community [HC]; Public Institution [PI}; Private Sector [PS] | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cerreta, M.; Giovene di Girasole, E. Towards Heritage Community Assessment: Indicators Proposal for the Self-Evaluation in Faro Convention Network Process. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239862

Cerreta M, Giovene di Girasole E. Towards Heritage Community Assessment: Indicators Proposal for the Self-Evaluation in Faro Convention Network Process. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):9862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239862

Chicago/Turabian StyleCerreta, Maria, and Eleonora Giovene di Girasole. 2020. "Towards Heritage Community Assessment: Indicators Proposal for the Self-Evaluation in Faro Convention Network Process" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 9862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239862

APA StyleCerreta, M., & Giovene di Girasole, E. (2020). Towards Heritage Community Assessment: Indicators Proposal for the Self-Evaluation in Faro Convention Network Process. Sustainability, 12(23), 9862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239862