Does Social Capital Matter for Total Factor Productivity? Exploratory Evidence from Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- −

- the creation, transmission, and absorption of knowledge (in particular: R&D, trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), which are a knowledge transfer channel and are necessary for the effective implementation of new technologies);

- −

- factor supply and efficient allocation—human capital, physical infrastructure, physical capital, structural change, and the financial system;

- −

- institutions, integration and policy—(Among others, democracy vs. autocracy, the location of countries and their overall economic development such as per capita income levels and inflation);

- −

- competition, social dimension, and the environment.

- Reducing transaction costs; social norms can work to reduce “transaction costs” by generating expectations, informal rules and shared understandings that allow people to conduct their personal interactions and business dealings efficiently. Reducing transaction costs; thus, it is crucial for the efficient functioning of modern economies [51,52,53] and the optimisation of the size of an organisation to maximise efficiency [54]. Social capital lowers uncertainty [55,56]. Trust within social networks serves as a substitute for a legal system; for example, in contract monitoring and enforcement. When fewer resources have to be used for securing individuals and firms from theft and other dishonest practices, more resources can be devoted to production and improving technology. This also means that investment decisions can be made using a longer time horizon, and it is possible to invest in riskier, but eventually more productive, projects [57].

- Facilitating the dissemination of information, knowledge and innovations; social capital—foster the diffusion of information and knowledge [58,59,60], not only among the workers of the same firm, but also through the professional networks and relationships with friends and former colleagues. In this way, it also helps to use various company resources, including intangible ones, such as intellectual capital [61]. These ties enable to lower the cost and time of information search and exchange, as well as allow to adopt innovations earlier. Hence, in this sense, social capital also contributes to the economy’s absorptive capacity, which is very important for productivity [27,57].

- Promoting cooperative and/or socially minded behaviour [56]; several researchers reported that social capital contributes to efficiency by enabling collaboration between individuals with conflicting interests towards the achievement of increased output, and allows more effective use of resources and fair distribution [32,62,63]. Many social norms have evolved to limit self-interested behaviour and to encourage cooperation in such circumstances. Within organisations, a workplace culture of openness and trust can promote cooperation and information sharing among staff, and thereby advance corporate goals. Such a culture may override the narrow self-interest of each staff member, which might be to withhold information from colleagues, who are often potential competitors for promotion or others favoured within that organisation. Networks are claimed to have a synergy effect, bringing together skills and different ideas which may lead to radical breakthroughs, remarkably improving productivity [64]. Social capital enhances productivity and value development in teams through enabling collaboration among the team members using virtual or face-to-face contact [53].

- Does social capital affect TFP in Polish regions?

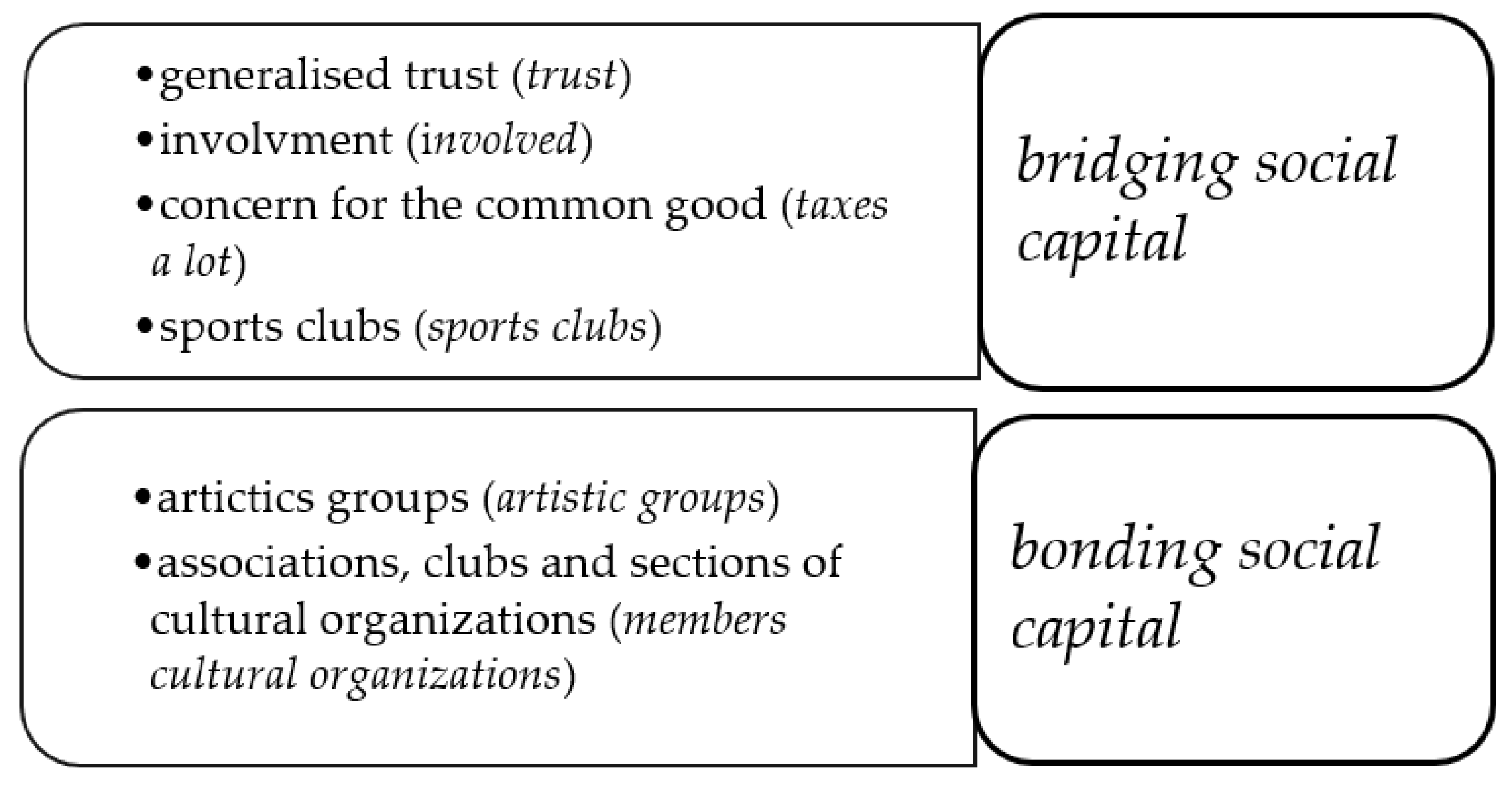

- Which type of capital, bridging or bonding, is good for TFP?

- H#1: Bridging social capital is one of the factors significantly influencing the level of TFP in Poland.

- H#2: Bonding social capital is one of the factors significantly influencing the level of TFP in Poland.

- H#3: Bridging social capital has a positive effect on TFP levels in Polish regions.

- H#4: Bonding social capital has a negative effect on TFP levels in Polish regions.

2. Methods

2.1. TFP

2.2. The Impact of Social Capital on TFP—Technique, Data and Variables

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of TFP in Poland

3.2. Social Capital in Polish Regions

3.3. Econometric Analysis of the Impact of Social Capital on TFP

- H#1—whether ;

- H#2—whether ≠ 0;

- H#3—whether ;

- H#4—whether

- the level of GDP per capita (GDP per capita)

- share of employed in sector III (III sector)

- level of entrepreneurship (SME)

- the age structure of the population—demographic characteristics of inhabitants (non-working)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- social capital is an essential factor of productivity;

- the context of the post-transformation economy is vital in the case of a culturally, socially and politically conditioned factor;

- this context is still hardly recognised;

- although it may be crucial for further long-term economic growth.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Description | Unit of Measurement | Source | Available for: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | Total factor productivity | - | Own calculation based on data from Statistics Poland | 2000–2016 |

| trust | generalised trust | the percentage of positive answers to the question: “can most people be trusted?” (1 = “most people can be trusted”) | Social Diagnosis | Every two years from 2003 to 2015 |

| involved | commitment | the percentage of positive answers to the question: “Did you get involved in the local community this year? (1 = “yes”) | Social Diagnosis | 2000 and every two years from 2003 to 2015 |

| taxes a lot | concern for the common good | participation of the answer “a lot” to the question “How much do you care that someone pays taxes less than they should?” (4 = “I care a lot”) | Social Diagnosis | Every two years from 2005 to 2015 |

| artistic groups | artistic groups per 1000 inhabitants | number per 1000 inhabitants | Statistics Poland | 2007, 2009, 2011–2016 |

| sports clubs | sports clubs per 1000 inhabitants | number per 1000 inhabitants | Statistics Poland | 2000–2002 and 2004–2016 and every two years |

| members cultural organisations | Members of associations, clubs and sections of cultural organisations per 1000 inhabitants | number per 1000 inhabitants | Statistics Poland | 2007, 2009, 2011–2016 |

| education | Participation of the economically active with higher education in the economically active total | percentage | Statistics Poland | 2000–2016 |

| non-working | Number of people in non-working age per 100 people in working age | percentage | Statistics Poland | 2002–2016 |

| employed foreign capital | Number of persons employed in entities with foreign capital per 100 total employees | number per 100 employees | Statistics Poland | 2003–2016 |

| SME | The number of SMEs per 1000 people of working age | number per 1000 people of working age | Statistics Poland | 2005–2016 |

| III sector | Share of employed in sector III | percentage | Statistics Poland | 2000–2016 |

References

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future—Call for Action*. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdgate, M.W. The sustainable use of tropical coastal resources—A key conservation issue. Ambio 1993, 22, 481–482. [Google Scholar]

- Dańska-Borsiak, B. Determinants of Total Factor Productivity in Visegrad Group Nuts-2 Regions. Acta Oecon. 2018, 68, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welfe, W. A Knowledge-Based Economy: New Directions of Macromodelling. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2008, 14, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, M. Resource and Output Trends in the United States Since 1870; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1956; pp. 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, D.W.; Griliches, Z. The Explanation of Productivity Change. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1967, 34, 249–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Goulder, L.; Daily, G.; Ehrlich, P.; Heal, G.; Levin, S.; Mäler, K.-G.; Schneider, S.; Starrett, D.; et al. Are We Consuming Too Much? J. Econ. Perspect. 2004, 18, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.J.; Dasgupta, P.; Goulder, L.H.; Mumford, K.J.; Oleson, K. Sustainability and the measurement of wealth. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2012, 17, 317–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, V.; Landau, S.; Welham, S.J. Measuring sustainability. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 1994, 1, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B. Sustainability Assessment: A Review of Values, Concepts, and Methodological Approaches; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the Immeasurable? Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-1-84407-299-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.W.; Lorne, F.T. Understanding and Implementing Sustainable Development; Nova Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-1-59033-796-7. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam, J. Sense and sustainability: Sustainability as an objective in international agricultural research. Agric. Econ. 1989, 3, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.X. Sustainability of China’s Growth Model: A Productivity Perspective. China World Econ. 2016, 24, 42–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Gawankar, S.A. Sustainable Industry 4.0 framework: A systematic literature review identifying the current trends and future perspectives. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 117, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrchota, J.; Pech, M.; Rolínek, L.; Bednář, J. Sustainability Outcomes of Green Processes in Relation to Industry 4.0 in Manufacturing: Systematic Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoa, M.; Román, V.M.-S.; Pérez, P. Do R&D activities matter for productivity? A regional spatial approach assessing the role of human and social capital. Econ. Model. 2017, 60, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, D.; Pieri, F. R&D offshoring and the productivity growth of European regions. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1581–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, D.T.; Helpman, E.; Hoffmaister, A.W. International R&D spillovers and institutions. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2009, 53, 723–741. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, R.; Redding, S.; van Reenen, J. Mapping the Two Faces of R&D: Productivity Growth in a Panel of OECD Industries. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2004, 86, 883–895. [Google Scholar]

- Pop Silaghi, M.I.; Alexa, D.; Jude, C.; Litan, C. Do business and public sector research and development expenditures contribute to economic growth in Central and Eastern European Countries? A dynamic panel estimation. Econ. Model. 2014, 36, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabadi, A.; Kimiaei, F.; Afzali, M.A. The Evaluation of Impacts of Knowledge-Based Economy Factors on the Improvement of Total Factor Productivity (a Comparative Study of Emerging and G7 Economies). J. Knowl. Econ. 2018, 9, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S. Openness, Productivity and Growth: What Do We Really Know? Econ. J. 1998, 108, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalles, J.T.; Tavares, J. Trade, scale or social capital? Technological progress in poor and rich countries. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2015, 24, 767–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F.; Rodrik, D. Trade Policy and Economic Growth: A Skeptic’s Guide to Cross-National Evidence; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Dettori, B.; Marrocu, E.; Paci, R. Total Factor Productivity, Intangible Assets and Spatial Dependence in the European Regions. Reg. Stud. 2012, 46, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, A. Determinants of Total Factor Productivity: A Literature Review; UNIDO: Vienna, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ortego-Marti, V. Loss of skill during unemployment and TFP differences across countries. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2017, 100, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Salinas-Jiménez, M.M.; Salinas-Jiménez, J. Corruption and total factor productivity: Level or growth effects? Port. Econ. J. 2011, 10, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, M.C.; Severgnini, B. Total factor productivity convergence in German states since reunification: Evidence and explanations. J. Comp. Econ. 2018, 46, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erken, H.; Donselaar, P.; Thurik, R. Total factor productivity and the role of entrepreneurship. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 1493–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knack, S.; Keefer, P. Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 1251–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, E. Needed: A Theory of Total Factor Productivity. Int. Econ. Rev. 1998, 39, 525–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Demokracja w Działaniu: Tradycje Obywatelskie we Współczesnych Włoszech; Wydawnictwo Znak: Kraków, Poland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Social capital and the modern capitalist economy: Creating a high trust workplace. Stern Bus. Mag. 1997, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Grootaert, C. Social Capital: The Missing Link? Social Capital Initiative; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Smulders, S. Bridging and Bonding Social Capital: Which Type is Good for Economic Growth; European Regional Science Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2003; pp. 147–184. [Google Scholar]

- Blume, L.; Sack, D. Patterns of social capital in West German regions. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2008, 15, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growiec, K.; Growiec, J. The Impact of Bridging and Bonding Social Capital on Individual Earnings: Evidence for an Inverted U; NBP: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, B. Bridging and Bonding: A Multidimensional Approach to Regional Social Capital; Martin Prosperity Institute: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, F. Social capital and the quality of economic development. Kyklos 2008, 61, 466–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, S.; Halpern, D.; Fitzpatrick, S. Social Capital: A Discussion Paper; Performance and Innovation Unit: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Poder, T.G. What is Really Social Capital? A Critical Review. Am. Soc. 2011, 42, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, B.; Roberts, J. Social capital: Exploring the theory and empirical divide. Empir. Econ. 2020, 58, 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubos, R. Social Capital: Theory and Research; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-351-49053-5. [Google Scholar]

- Schuller, T.; Field, J.; Baron, S. Social Capital: A Review and Critique. In Social Capital: Critical Perspectives; Baron, S., Field, J., Schuler, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Productivity Commission. Social Capital: Reviewing the Concept and its Policy Implications; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Social capital, civil society and development. Third World Q. 2001, 22, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. AMR 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözbilir, F. The interaction between social capital, creativity and efficiency in organisations. Think. Skills Creat. 2018, 27, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jankauskas, V.; Šeputienė, J. The relation between social capital, governance and economic performance in Europe. Bus. Theory Pract. 2007, 8, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Méon, P.-G. The Productivity of Trust. World Dev. 2015, 70, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasa, A. Social Capital, Institutional Quality and Productivity: Evidence from European Regions. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 9, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F. Does social capital improve labour productivity in Small and Medium Enterprises? Int. J. Manag. Decis. Mak. 2008, 9, 454–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, E.; Shin, I. Heterogeneity, Trust, Human Capital and Productivity Growth: Decomposition Analysis. J. Econ. Econom. 2012, 55, 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Van Schaik, T. Social capital and growth in European regions: An empirical test. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2005, 21, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska, A. Zarządzanie kapitałem intelektualnym w małym przedsiębiorstwie; Polskie Towarzystwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.D.; Ashman, D. Participation, social capital, and intersectoral problem solving: African and Asian cases. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.J. Observations on social capital. In Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective; Dasgupta, P., Seregeldin, I., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kaasa, A. Effects of different dimensions of social capital on innovative activity: Evidence from Europe at the regional level. Technovation 2009, 29, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M. The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. Can. J. Policy Res. 2001, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.-W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.J.; Prusak, L. In good company: How social capital makes organisations work. Ubiquity 2001, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q. Trust, Social Capital and Organizational Effectiveness; Virginia Tech: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aghion, P.; Algan, Y.; Cahuc, P.; Shleifer, A. Regulation and distrust. Q. J. Econ. 2010, 125, 1015–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; De Groot, H.L.; Van Schaik, A.B. Trust and economic growth: A robustness analysis. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2004, 56, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C. How does social trust affect economic growth? South. Econ. J. 2012, 78, 1346–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearmon, J.; Grier, K. Trust and development. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2009, 71, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabellini, G. Culture and institutions: Economic development in the regions of Europe. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2010, 8, 677–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.; Johnson, P.A. Social capability and economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1998, 113, 965–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, P.F. Economic growth and social capital. Polit. Stud. 2000, 48, 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, P.J.; Knack, S. Trust and growth. Econ. J. 2001, 111, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F. Economic Growth and Social Capital in Asia; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, G.; Plümper, T.; Baumann, S. Bringing Putnam to the European Regions on the Relevance of Social Capital for Economic Growth. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2000, 7, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. Civic Capital as the Missing Link; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, E.C. Moral Basis of a Backward Society; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bilson, J.F. Civil liberty—An econometric investigation. Kyklos 1982, 35, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volland, B. Trust, Confidence and Economic Growth: An. Evaluation of the Beugelsdijk Hypothesis; Jena Economic Research Papers; Friedrich Schiller University and Max Planck Institute of Economics: Jena, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, D.L.; Kahn, M.E. Understanding the American decline in social capital, 1952–1998. Kyklos 2003, 56, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacinto, V.D.; Nuzzo, G. Explaining labour productivity differentials across Italian regions: The role of socio-economic structure and factor endowments. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2006, 85, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Ibrahim, M.H.; Mirakhor, A. Ethical behavior and trustworthiness in the stock market-growth nexus. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2015, 33, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijek, A.; Kijek, T. Nonlinear Effects of Human Capital and R&D on TFP: Evidence from European Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komare, L. Determinants of total factor productivity in eight european countries. J. Econ. Manag. Res. 2018, 7, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C. Corruption and Social Capital; Citeseer: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Claridge, T. Is Corruption a Dark Side of Social Capital? Correlation or Causality? Available online: https://www.socialcapitalresearch.com/corruption-dark-side-social-capital-correlation-causality/ (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Rothstein, B.; Uslaner, E.M. All for All: Equality, Corruption, and Social Trust. World Polit. 2005, 58, 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, F.; Wallace, C. Patterns of Formal and Informal Social Capital in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, F. Mapping social capital across Europe: Findings, trends and methodological shortcomings of cross-national surveys. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2008, 47, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowski, J.; Jasińska-Kania, A. Voluntary organisations and the development of civil society. In European Values at the Turn of the Millennium; Arts, W.A., Halman, L., Eds.; Brill Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Fidrmuc, J.; Gërxhani, K. Mind the gap! Social capital, East and West. J. Comp. Econ. 2008, 36, 264–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paldam, M.; Svendsen, G.T. Missing Social Capital and the Transition in Eastern Europe. J. Inst. Innov. Dev. Transit. 2001, 5, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, F.; Makarovic, M.; Roncevic, B.; Tomsic, M. The Challenges of Sustained Development: The Role of Socio-cultural Factors in East-Central Europe; Central European University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-963-9241-96-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova, D. Social Capital in Central and Eastern Europe. A Critical Assessment and Litererature Review; Central European University: Budapeszt, Hungary, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Młokosiewicz, M. Social capital in Poland compared to other member states—The analysis of the phenomenon at macro-level. Sociology 2009, 2, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiser, M.; Haerpfer, C.; Nowotny, T.; Wallace, C. Social Capital in Transition: A First Look at the Evidence. Sociol. Časopis Czech Sociol. Rev. 2002, 38, 693–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.; Pichler, F. Bridging and Bonding Social Capital: Which is More Prevalent in Europe. Eur. J. Soc. Sec. 2007, 9, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIESR; IVIE; The University of Valencia. TFP Growth: Drivers, Components and Frontier Firms; Prepared for the European Commission, DG GROW, under Specific Contract; NIESR: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Janc, K. Zróżnicowanie Przestrzenne Kapitału Ludzkiego i Społecznego w Polsce; Institute of Geography and Regional Development, University of Wrocławski: Wrocław, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, J. Kraina nieufności: Kapitał społeczny, rozwój gospodarczy i sprawność instytucji publicznych w polskiej literaturze akademickiej. In Szafarze Darów Europejskich. Kapitał Społeczny a Realizacja Polityki Regionalnej w Polskich Województwach; Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarski, T. Przestrzenne zróżnicowanie łącznej produkcyjności czynników produkcji w Polsce. Gospod. Narodowa 2010, 238, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semykina, A.; Wooldridge, J.M. Estimating panel data models in the presence of endogeneity and selection. J. Econom. 2010, 157, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 5th ed.; Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-111-53104-1. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. Introduction to Econometrics, 4th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thrane, C. On the Relationship between Length of Stay and Total Trip Expenditures: A Case Study of Instrumental Variable (IV) Regression Analysis. Tour. Econ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Pinto, P. Social Capital as a Capacity for Collective Action. In Assessing Social Capital: Concept, Policy and Practice; Cambridge Scholars Publishing in association with GSE Research: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2012; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Działek, J. Kapitał Społeczny Jako Czynnik Rozwoju Gospodarczego w Skali Regionalnej i Lokalnej w Polsce; Jagiellonian University Publishing: Cracow, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski, J. Więź społeczna a aktywność stowarzyszeniowa. In Teorie Wspólnotowe a Praktyka Społeczna; Gniewkowska, A., Gliński, P., Kościański, A., Eds.; IFiS: Warszawa, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Kapitał Społeczny na Poziomie Mezo—Współpraca Organizacji Trzeciego Sektora; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Downward, P.; Pawlowski, T.; Rasciute, S. Trust, Trustworthiness, Relational Goods and Social Capital: A Cross-Country Economic Analysis; North American Association of Sports Economists. 2011. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/spe/wpaper/1110.html (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Markowska-Przybyła, U.; Ramsey, D. The Association between Social Capital and Membership of Organisations amongst Polish Students. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Skrok, Ł.; Majcherek, D.; Nałęcz, H.; Biernat, E. Impact of sports activity on Polish adults: Self-reported health, social capital & attitudes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS Kultura fizyczna w latach 2017 i 2018. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/kultura-turystyka-sport/sport/kultura-fizyczna-w-latach-2017-i-2018,1,5.html (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- Hlavacek, P.; Bal-Domańska, B. Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Economic Growth in Central and Eastern European Countries. Inz. Ekon. Eng. Econ. 2016, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.; Tamura, R.; Mulholland, S.E. How important are human capital, physical capital and total factor productivity for determining state economic growth in the United States, 1840–2000? J. Econ. Growth 2013, 18, 319–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, T.; Parhi, M.; Diebolt, C. Human capital accumulation and spatial TFP interdependence. Hist. Soc. Res. 2008, 33, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dańska-Borsiak, B.; Laskowska, I. The Determinants of Total Factor Productivity in Polish Subregions. Panel Data Analysis. Comp. Econ. Res. 2012, 15, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciołek, D.; Brodzicki, T. Spatial Dependence Structure of Total Factor Productivity in Polish Local Administrative Districts. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Oecon. 2017, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowska-Przybyła, U. Diagnoza Zasobów Kapitału Społecznego w Rozwoju Regionalnym Polski z Wykorzystaniem Metody EKONOMII eksperymentalnej; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, T.P. Making Capitalism Work: Social Capital and Economic Growth in Italy, 1970–1995; Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei: Milan, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Higón, D.A.; Mañez, J.A.; Rochina-Barrachina, M.E.; Sanchis, A.; Sanchis, J.A. The impact of the Great Recession on TFP convergence among EU countries. J. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2017, 25, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarzewska-Borowiec, I.E. Łączna produktywność czynników produkcji (TFP) i jej zróżnicowanie w krajach członkowskich Unii Europejskiej. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Oecon. 2018, 3, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Prochniak, M. Changes in Total Factor Productivity. In Poland. Competitiveness Report 2016. The Role of Economic Policy and Institutions; World Economy Research Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2016; pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sarracino, F.; Mikucka, M. Social Capital in Europe from 1990 to 2012: Trends and Convergence. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 131, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organisations Across Nations; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1-4522-0793-3. [Google Scholar]

- Åberg, M.; Sandberg, M. Social Capital and Democratisation: Roots of Trust in Post-Communist Poland and Ukraine; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-7546-1936-9. [Google Scholar]

- Badescu, G.; Uslaner, E. Social Capital and the Transition to Democracy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-415-25814-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, R. Getting Things Done in an Anti-modern Society: Social Capital Networks in Russia. In Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective; Dasgupta, P., Seregeldin, I., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, R.; Mishler, W.; Haerpfer, C. Social capital in civic and stressful societies. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 1997, 32, 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunioka, T.; Woller, G.M. In (a) democracy we trust: Social and economic determinants of support for democratic procedures in central and eastern Europe. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 1999, 28, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif, A. Cultural Beliefs and the Organization of Society: A Historical and Theoretical Reflection on Collectivist and Individualist Societies. J. Polit. Econ. 1994, 102, 912–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubun, K. Social capital may mediate the relationship between social distance and COVID-19 prevalence. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.09939. [Google Scholar]

- Elgar, F.J.; Stefaniak, A.; W ohl, M.J.A. The trouble with trust: Time-series analysis of social capital, income inequality, and COVID-19 deaths in 84 countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovi, F.; Andrieu, E. Bowling Together by Bowling Alone: Social Capital and COVID-19. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkoski, V.; Utkovski, Z.; Jolakoski, P.; Tevdovski, D.; Kocarev, L. The socio-economic determinants of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.07947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Miao, X.; Lu, X.; Ma, X.; Guo, X. The Emergence of a COVID-19 Related Social Capital: The Case of China. Int. J. Sociol. 2020, 50, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, D.; Li, S.; Yang, N. Social Capital and Sleep Quality in Individuals Who Self-Isolated for 14 Days During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in January 2020 in China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | TPF 2002 | TFP 2016 | TFP 2002–2016 | The Average Annual Growth of TFP Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 871.8 | 1277.0 | 35.81 | 2.76% |

| Kujawsko-pomorskie | 723.0 | 1063.1 | 32.57 | 2.79% |

| Lubelskie | 553.2 | 919.3 | 41.92 | 3.69% |

| Lubuskie | 728.6 | 976.5 | 22.36 | 2.11% |

| Łódzkie | 684.7 | 1087.5 | 40.99 | 3.36% |

| Małopolskie | 705.0 | 1143.0 | 39.73 | 3.51% |

| Mazowieckie | 961.1 | 1544.4 | 39.38 | 3.45% |

| Opolskie | 657.1 | 1020.0 | 39.46 | 3.19% |

| Podkarpackie | 643.5 | 950.6 | 32.87 | 2.83% |

| Podlaskie | 611.5 | 920.3 | 37.92 | 2.96% |

| Pomorskie | 826.8 | 1162.4 | 29.69 | 2.46% |

| Śląskie | 900.6 | 1260.7 | 27.27 | 2.43% |

| Świętokrzyskie | 626.2 | 955.1 | 38.62 | 3.06% |

| Warmińsko-mazurskie | 694.0 | 985.9 | 34.25 | 2.54% |

| Wielkopolskie | 805.1 | 1236.0 | 38.34 | 3.11% |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 787.3 | 1048.6 | 25.80 | 2.07% |

| Parameter | Value | Standard Error | t-Student Statistics | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α 0 | 0.098 | 0.051 | 1.899 | 0.078 |

| α1 | −0.011 | 0.008 | −1.345 | 0.200 |

| Variable | N | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Standard Deviation | Correlation with TFP (r-Pearson) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| trust | 240 | 0.040 | 0.280 | 0.124 | 0.034 | 0.238 *** |

| involved | 240 | 0.079 | 0.260 | 0.147 | 0.030 | 0.163 ** |

| taxes a lot | 240 | 0.088 | 0.236 | 0.159 | 0.033 | 0.433 *** |

| artistic groups | 240 | 0.229 | 0.805 | 0.459 | 0.110 | −0.571 *** |

| sports clubs | 240 | 0.131 | 0.622 | 0.345 | 0.094 | 0.080 |

| members cultural organizations | 240 | 0.403 | 16.181 | 7.316 | 3.851 | 0.596 *** |

| Variable | N | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFP | 240 | 553.17 | 1544.41 | 962.07 | 194.76 |

| education | 240 | 11.69 | 41.83 | 22.98 | 6.20 |

| employed foreign capital | 240 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| bridging sc | 240 | 0.74 | 2.64 | 1.64 | 0.41 |

| bonding sc | 240 | 0.21 | 1.90 | 0.84 | 0.32 |

| GDP per capita | 240 | 15,299.00 | 77,359.00 | 31,966.50 | 11,096.07 |

| SME | 240 | 1066.80 | 2414.80 | 1510.63 | 268.33 |

| III sector | 240 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.06 |

| non-working | 240 | 20.70 | 37.00 | 26.51 | 3.49 |

| OLS (1) | FE (2) | GLS (3) | IV (5) | IV (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| constant | 149.380 (73.181) | −65.801 (104.311) | −1.937 (91.181) | 564.813 (678.359) | 82.171 (406.514) |

| ln education | 418.039 (24.561) *** | 432.083 (27.586) *** | 427.036 (26.164) *** | 385.530 (120.792) *** | 371.893 (128.057) *** |

| ln employed foreign capital | 162.810 (8.038) *** | 117.890 (20.913) *** | 117.890 (16.355) *** | 318.697 (187.680) * | 165.148 (74.716) ** |

| bridging sc | 20.338 (69.627) | 181.093 (61.390) *** | 174.608 (60.113) *** | 1243.15 (465.705) *** | 1437.27 (440.647) *** |

| bonding sc | −85.160 (40.989) ** | −132.597 (42.123) *** | −134.224 (40.504) *** | −997.442 (244.716) *** | −958.753 (271.816) *** |

| Number of regions | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Number of periods | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| N | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| estimation method | OLS | FE | RE | TSLS FE | 2GSLS RE |

| R2 = 0.859 | LSDV R2 = 0.9503 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markowska-Przybyła, U. Does Social Capital Matter for Total Factor Productivity? Exploratory Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239978

Markowska-Przybyła U. Does Social Capital Matter for Total Factor Productivity? Exploratory Evidence from Poland. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):9978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239978

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkowska-Przybyła, Urszula. 2020. "Does Social Capital Matter for Total Factor Productivity? Exploratory Evidence from Poland" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 9978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239978

APA StyleMarkowska-Przybyła, U. (2020). Does Social Capital Matter for Total Factor Productivity? Exploratory Evidence from Poland. Sustainability, 12(23), 9978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239978