Multidisciplinary Composition of Climate Change Commissions: Transnational Trends and Expert Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Evolving Climate Change Governance Architecture: A Review

3. Justification, Materials and Methods

3.1. Justification

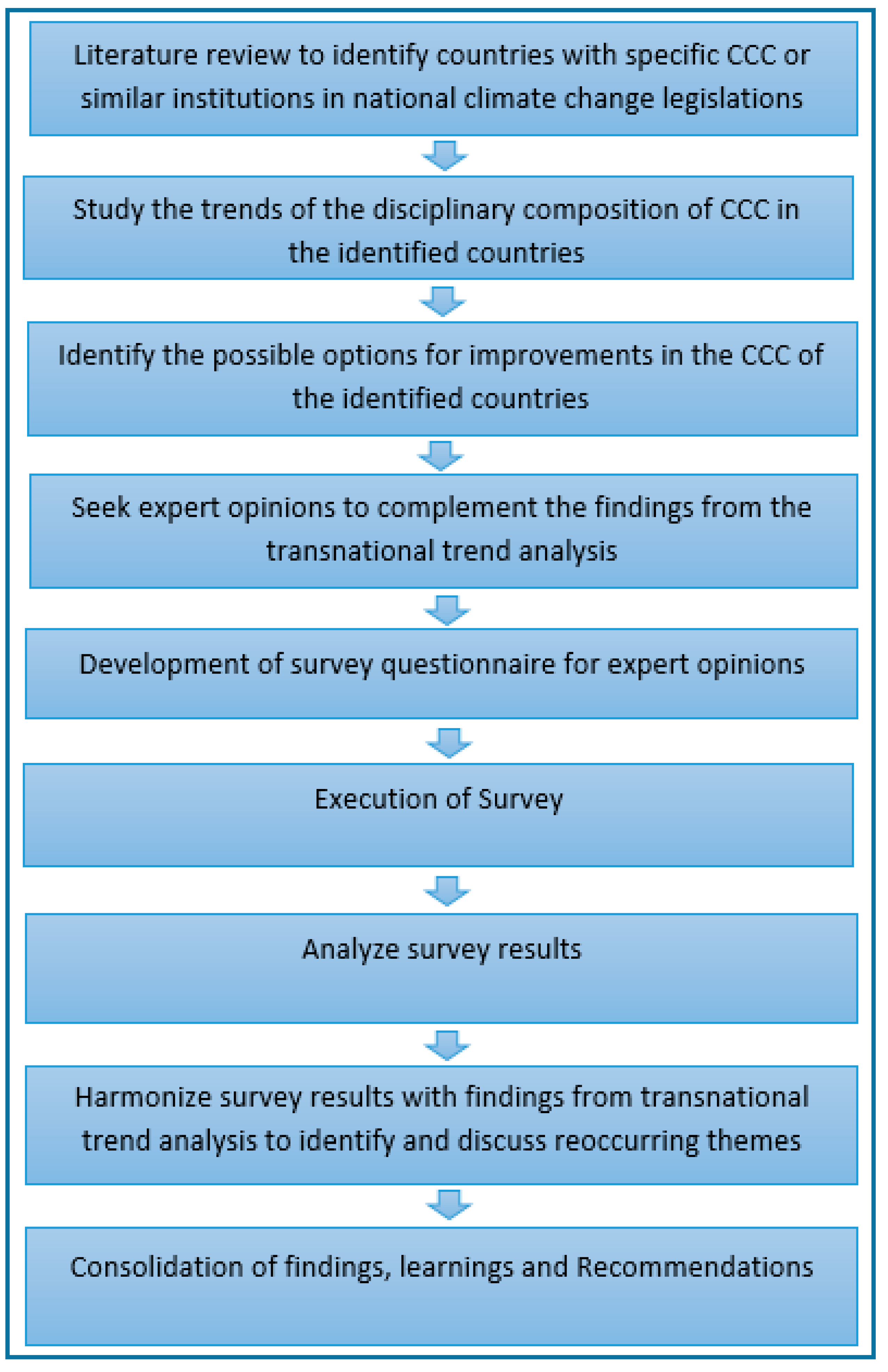

3.2. Materials and Methods

3.2.1. Participant Selection and Survey Administration

3.2.2. Method for Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Transnational Trends

4.2. Expert Survey Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. A Synthesis

5.2. Caveats on CCCs and Their Multidisciplinary Composition

5.3. Reflecting on Quasi-Institutions

5.4. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cribb, J. Surviving the 21st Century: Humanity’s Ten Great Challenges and How We Can Overcome Them; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.J. Super wicked problems and climate change: Restraining the present to liberate the future. Environ. Law Rep. 2010, 40, 10749–10756. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, K.; Cashore, B.; Bernstein, S.; Auld, G.; Levin, K.; Cashore, B.; Bernstein, S.; Auld, G. Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sci. 2012, 45, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobuta, G.; Dubash, N.K.; Upadhyaya, P.; Deribe, M.; Höhne, N. National climate change mitigation legislation, strategy and targets: A global update. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 1114–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barton, B.; Campion, J. Climate change legislation: Law for sound climate policy making. In Innovation in Energy Law and Technology: Dynamic Solutions for Energy Transitions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 23–37. ISBN 9780198822080. [Google Scholar]

- Eskander, S.M.S.U.; Fankhauser, S. Reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from national climate legislation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, S.L.; Steurer, R. Taking stock of climate change acts in Europe: Living policy processes or symbolic gestures? Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 1052–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachmany, M.; Fankhauser, S.; Setzer, J.; Averchenkova, A. Global Trends in Climate Change Legislation and Litigation; Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Heijden, J. Studying urban climate governance: Where to begin, what to look for, and how to make a meaningful contribution to scholarship and practice. Earth Syst. Gov. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, W.; Chelleri, L.; van Herk, S.; Zevenbergen, C. City-to-city learning within climate city networks: Definition, significance, and challenges from a global perspective. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weart, S. Rise of interdisciplinary research on climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Bruin, W.B.; Granger Morgan, M. Reflections on an interdisciplinary collaboration to inform public understanding of climate change, mitigation, and impacts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jagers, S.C.; Stripple, J. Climate Govenance beyond the State. Glob. Gov. 2003, 9, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, J.; Knieling, J. Conceptualising climate change governance. In Climate Change Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.; Huitema, D.; Van Asselt, H.; Forster, J. Governing Climate Change: Polycentricity in Action? Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, T.; Johnston, S. Global Environmental Problems and International Environmental Agreements: The Economics of International Institution Building; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J. International Cooperation on Climate Change: What Can other Regimes Teach Us? Available online: https://www.wri.org/blog/2012/05/international-cooperation-climate-change-what-can-other-regimes-teach-us (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Dowd, R.; McAdam, J. International cooperation and responsibility sharing to combat climate change: Lessons for international refugee law. Melb. J. Int. Law 2017, 18, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okereke, C.; Bulkeley, H.; Schroeder, H. Conceptualizing climate governance beyond the international regime. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asselt, H. The Fragmentation of Global Climate Governance: Consequences and Management of Regime Interactions; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhani, R. Understanding private-sector engagement in sustainable urban development and delivering the climate agenda in northwestern Europe—A case study of London and Copenhagen. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Nicol, D.; Niemeyer, S.; Pemberton, S.; Curato, N.; Bächtiger, A.; Batterham, P.; Bedsted, B.; Burall, S.; Burgess, M.; et al. Global citizen deliberation on genome editing. Science 2020, 369, 1435–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhetri, N.; Ghimire, R.; Wagner, M.; Wang, M. Global citizen deliberation: Case of world-wide views on climate and energy. Energy Policy 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Lankao, P.; Hughes, S.; Rosas-Huerta, A.; Borquez, R.; Gnatz, D.M. Institutional capacity for climate change responses: An examination of construction and pathways in Mexico City and Santiago. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 785–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Climate Change Governance; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kamarck, E. The Challenging Politics of Climate Change; The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deere-Birkbeck, C. Global governance in the context of climate change: The challenges of increasingly complex risk parameters. Int. Aff. 2009, 85, 1173–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham-Dukuma, M.C.; Okpaleke, F.N.; Hasan, Q.M.; Dioha, M.O. The limits of the offshore oil exploration ban and agricultural sector deal to reduce emissions in New Zealand. Carbon Clim. Law Rev. 2020, 14, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, P.G.; Kim Swales, J.; Winning, M.A. A review of the role and remit of the committee on climate change. Energy Policy 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, J. Developing a long-term climate change mitigation strategy. Polit. Sci. 2008, 60, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nullmeier, F. Knowledge and decision-making. In Democratization of Expertise? Democratization of Expertise? Exploring Novel Forms of Scientific Advice in Political Decision-Making; Maasen, S., Weingart, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Biesbroek, R.; Peters, B.G.; Tosun, J. Public bureaucracy and climate change adaptation. Rev. Policy Res. 2018, 35, 776–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biesbroek, R.; Lesnikowski, A.; Ford, J.D.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Vink, M. Do administrative traditions matter for climate change adaptation policy? A comparative analysis of 32 high-income countries. Rev. Policy Res. 2018, 35, 881–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munck af Rosenschöld, J.; Rozema, J.G.; Alex Frye-Levine, L. Institutional inertia and climate change: A review of the new institutionalist literature. Wires Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levitt, P.; Jaworsky, B.N. Transnational migration studies: Past developments and future trends. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2007, 33, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swanson, D.L. Transnational trends in political communication: Conventional views and new realities. In Comparing Political Communication: Theories, Cases, and Challenges; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; pp. 45–63. ISBN 9780511606991. [Google Scholar]

- Iriste, S.; Katane, I. Expertise as a research method in education. Rural Environ. Educ. Personal. 2018, 11, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, A.L.; Cunningham, S.W.; Banks, J.; Roper, A.T.; Mason, T.W.; Rossini, F.A. Forecasting and Management of Technology; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M.; Henrion, M. Uncertainty: A Guide to Dealing With Uncertainty in Quantitative Risk and Policy Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman, S.; Dowlatabadi, H.; Satterfield, T.; McDaniels, T. Expert views on biodiversity conservation in an era of climate change. Glob. Env. Chang. 2010, 20, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative content analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Scott, W., Metzler, K., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, S.; Watson, B.R.; Riffe, D.; Lovejoy, J. Issues and best practices in content analysis. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2015, 92, 791–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australia’s Climate Change Authority Who we are | Climate Change Authority. Available online: https://www.climatechangeauthority.gov.au/about-cca/who-we-are (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- The Finnish Climate Change Panel The Finnish Climate Change Panel—Ilmastopaneeli.fi. Available online: https://www.ilmastopaneeli.fi/en/ (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Norway’s Climate Risk Commission Norway’s Climate Risk Commission. Available online: https://nettsteder.regjeringen.no/klimarisikoutvalget/mandate/ (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- The Swedish Climate Policy Council The Swedish Climate Policy Council | Klimatpolitiska Rådet. Available online: https://www.klimatpolitiskaradet.se/en/summary-in-english/ (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Spash, C.L. The development of environmental thinking in economics. Environ. Values 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Ecological economics: Themes, approaches, and differences with environmental economics. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munda, G. Environmental economics, ecological economics, and the concept of sustainable development. Environ. Values 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norgaard, R.B. Environmental economics: An evolutionary critique and a plea for pluralism. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessai, S.; Lu, X.; Risbey, J.S. On the role of climate scenarios for adaptation planning. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsafon, B.E.K.; Butu, H.M.; Owolabi, A.B.; Roh, J.W.; Suh, D.; Huh, J.S. Integrating multi-criteria analysis with PDCA cycle for sustainable energy planning in Africa: Application to hybrid mini-grid system in Cameroon. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski, J.E.; Xie, H.; Olson, I.R. Understanding social hierarchies: The neural and psychological foundations of status perception. Soc. Neurosci. 2015, 10, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harré, N. Psychology for a Better World: Strategies to Inspire Sustainability; Department of Psychology, University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lachapelle, E.; Borick, C.P.; Rabe, B. Public attitudes toward climate science and climate policy in federal systems: Canada and the United States compared: Public attitudes toward climate science and climate policy in federal systems. Rev. Policy Res. 2012, 29, 334–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziegler, A. Political orientation, environmental values, and climate change beliefs and attitudes: An empirical cross country analysis. Energy Econ. 2017, 63, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Shao, M.; Gale, W.; Li, L. Global pattern of soil carbon losses due to the conversion of forests to agricultural land. Sci. Rep. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, L.H.; Barbosa, S.; Bhadwal, A.; Cowie, K.; Delusca, D.; Flores-Renteria, K.; Hermans, E.; Jobbagy, W.; Kurz, D.; Li, D.; et al. Climate Change and Land: Land degradation; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Burck, J.; Hagen, U.; Höhne, N.; Nascimento, L.; Bals, C. The Climate Change Performance Index 2020; Germanwatch Nord-Süd Initiative eV: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf, F.W. Games Real Actors Play: Actor-Centered Institutionalism in Policy Research; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018; ISBN 9780429968822. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document: Report from The Commission to the European Parliament and The Council on the Implementation of the EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change; European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, F.; Leal Filho, W.; Casaleiro, P.; Nagy, G.J.; Diaz, H.; Quasem Al-Amin, A.; Baltazar Salgueirinho Osório de Andrade Guerra, J.; Hurlbert, M.; Farooq, H.; Klavins, M.; et al. Climate change policies and agendas: Facing implementation challenges and guiding responses. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 104, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torney, D. Environmental politics climate laws in small European states: Symbolic legislation and limits of diffusion in Ireland and Finland. Environ. Polit. 2019, 28, 1124–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torney, D. If at first you don’t succeed: The development of climate change legislation in Ireland. Ir. Polit. Stud. 2017, 32, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, M.I.; Dougill, A.J.; Stringer, L.C.; Vincent, K.E.; Pardoe, J.; Kalaba, F.K.; Mkwambisi, D.D.; Namaganda, E.; Afionis, S. Climate change adaptation and cross-sectoral policy coherence in southern Africa. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 2059–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Somanathan, E.; Sterner, T.; Sugiyama, T.; Chimanikire, D.; Dubash, N.K.; Essandoh-Yeddu, J.K.; Fifita, S.; Goulder, L.; Jaffe, A.; Labandeira, X.; et al. National and Sub-National Policies and Institutions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dioha, M.O.; Abraham-Dukuma, M.C.; Bogado, N.; Okpaleke, F.N. Supporting climate policy with effective energy modelling: A perspective on the varying technical capacity of South Africa, China, Germany and the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andonova, L.B.; Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H. Transnational climate governance. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2009, 9, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Andonova, L.B.; Betsill, M.M.; Compagnon, D.; Hale, T.; Hoffmann, M.J.; Newell, P.; Paterson, M.; Roger, C.; Vandeveer, S.D. Transnational Climate Change Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781107706033. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H. Governance and the geography of authority: Modalities of authorisation and the transnational governing of climate change. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 2428–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Gregorio, M. Building authority and legitimacy in transnational climate change governance: Evidence from the governors’ climate and forests task force. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 64, 102126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category 1 | Legal | i.e., law/policy/international relations |

| Category 2 | Industry | i.e., energy/transport/agriculture/food |

| Category 3 | Biosciences | i.e., biology/oceanography/biodiversity/biotechnology/Geography/geology/meteorology/hydrology/forestry |

| Category 4 | Economics | i.e., finance/economic |

| Category 5 | Planning | i.e., engineering/development/management |

| Category 6 | Social Sciences | i.e., psychology/sociology/anthropology/history/political science/education |

| Category 7 | Ethics | i.e., religion/philosophy/moral |

| Category 8 | Governance | i.e., politicians/interest groups/community groups |

| Category 9 | Health | i.e., medicine/public health/environmental health |

| Category 10 | Communication | i.e., media/marketing |

| Category 11 | Uncategorized |

| Country | Institution | Establishment | Summary of Objectives | Disciplinary Composition | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Climate Change Authority | Climate Change Authority Act 2011 |

| Not specifically prescribed. The law requires a Chair to head the Authority, a Chief Scientist and up to seven other members. However, at the time of writing, the Authority’s membership was composed of experts from the domains of public policy, energy, business and economics, agriculture, maritime science, numerical modelling, and engineering [43]. | There is an opportunity to incorporate a wide multidisciplinary composition of experts, even as Australia considers a bill to abolish the existing Climate Change Authority for a new Climate Change Commission. The present Authority could be reconfigured to include more diversity of experts. Alternatively, the likely successor commission could also consider the results of this study. |

| Denmark | The Danish Council on Climate Change (The Climate Council) | Climate Change Act 2014 and the Climate Act 2019 |

| Experts with broad expertise in energy, buildings, transport, agriculture, environment, nature, economy, climate science and behavioural research. | The Climate Council shows relevant multidisciplinary composition, but there remains an opportunity to incorporate a wide multidisciplinary composition of experts with other relevant skills. |

| Finland | Scientific Expert Body—Finland’s Climate Panel (The Finnish Climate Change Panel) | Climate Change Act 2015 |

| Not specifically prescribed, but the law requires the representation of different fields of science in the expert body. | At the time of writing, the Panel’s members represented different branches of science from educational sciences to atmospheric sciences [44]. However, there is an opportunity for the law to specifically prescribe multidisciplinary fields of expertise. |

| France | High Council on Climate Change | Law No. 2019-1147 on Energy and the Climate and Executive promulgation in November 2018 |

| Scientific, technical and economic expertise in the fields of climate and ecosystem sciences, the reduction of GHG emissions, adaptation and resilience to climate change. | The multidisciplinary character of the High Council on Climate Change aligns with the logic of an ideal framework, but needs broader multidisciplinary. composition for well-informed and efficacious policymaking. |

| Germany | Council of Experts on Climate Change | Climate Protection Act 2019 |

| Five specialized persons from the fields of climatology, environmental science and social matters; and possessing outstanding scientific knowledge and experience in required prescribed fields. | Similar to New Zealand’s CCC, Germany’s Council of Experts on Climate Change evinces an array of relevant multidisciplinary fields. This framework can also potentially support well-informed climate policy responses, although it is still possible to capture other multidisciplinary fields and industry components. |

| Ireland | The Climate Change Advisory Council | Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Act 2015 |

| Not prescribed, but the establishing law provides that, in constituting the membership of the Advisory Council, the Government shall have regard to the range of qualifications, expertise and experience necessary for the proper and effective performance of the functions of the Advisory Council. | There is a clear acknowledgement in the law of the need to appoint experts with requisite expertise and experience into the Climate Change Advisory Council. The lack of useful prescription of the required experts or fields of expertise presents a good opportunity for the Irish Republic to amend its climate change law. This study becomes useful in this respect. |

| New Zealand | Climate Change Commission | Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019 |

| Understanding of climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as likely effects of policy responses; work experience with local and central governments; knowledge of public policy and regulatory processes; technical and professional skills, experience, and expertise in, and an understanding of innovative approaches relevant to the environmental, ecological, social, economic and distributional effects of policy interventions; sectoral representation at regional and local levels. | The multidisciplinary and multidimensional spectra of New Zealand’s CCC represent a robust framework for formulating well-informed climate policy responses. |

| Norway | Climate Risk Commission | Executive appointment pursuant to the Climate Act 2018 |

| Not prescribed. | Not an ideal CCC that provides a living framework for continuous advisory functions. The Norwegian Climate Risk Commission seems to rather be a financial risk-prevention commission that was to deliver its recommendation on climate risks in Norway by 14 December 2018 [45]. |

| Philippines | Climate Change Commission | Republic Act No. 9729 (Climate Change Act 2009) |

| Not prescribed. The establishment legislation presupposes an “independent autonomous” institution, but also requires the country’s President to serve as Chairman of the CCC. The President, as Chairman, can then appoint three Commissioners. | Two key areas in need of consideration include: the practical autonomy/independence of the CCC and capturing multidisciplinary fields. |

| Sweden | Climate Policy Council | Climate Act 2017 and the Swedish Climate Policy Framework |

| Not specifically prescribed. However, at the time of writing, the Council comprised members from the fields of political science, environmental social science, industrial energy policy, economics, climatology, and environmental history [46]. | The absence of disciplinary composition requirements of the Climate Policy Council represents a policy gap. This can be filled by the prescription of suitable multidisciplinary fields. |

| United Kingdom | Committee on Climate Change | Climate Change Act 2008 (Amended in 2019) |

| Experience and knowledge in business competitiveness; climate policy and its national impact; climate science and other branches of environmental science; understanding of the peculiarities of the four British countries—England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland; economics analysis and forecasting; emissions trading; energy production and supply; financial investment; technology development and diffusion. | This premier climate governance framework provides an early insight for understanding the modalities for enacting a dedicated climate change legislation, as well as instituting a multidisciplinary CCC. |

| Characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Age (Years) | IN | ES | AD | MI | EP |

| Australia | 9 | ◯ | ◯ | ⊙ | ◯ | ☐ |

| Denmark | 6 | ⊙ | ◯ | ⊙ | ◯ | ⊙ |

| Finland | 5 | ⊙ | ☐ | ◯ | ◯ | ⊙ |

| France | 1 | ⊙ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ⊙ |

| Germany | 1 | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ☐ |

| Ireland | 5 | ⊙ | ☐ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| New Zealand | 1 | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ☐ |

| Norway | 2 | ⊙ | ☐ | ⊙ | ◯ | ⊙ |

| Philippines | 11 | ◯ | ☐ | ◯ | ⊙ | ◯ |

| Sweden | 3 | ◯ | ◯ | ⊙ | ◯ | ☐ |

| United Kingdom | 12 | ⊙ | ◯ | ⊙ | ◯ | ⊙ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abraham-Dukuma, M.C.; Dioha, M.O.; Bogado, N.; Butu, H.M.; Okpaleke, F.N.; Hasan, Q.M.; Epe, S.B.; Emodi, N.V. Multidisciplinary Composition of Climate Change Commissions: Transnational Trends and Expert Perspectives. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410280

Abraham-Dukuma MC, Dioha MO, Bogado N, Butu HM, Okpaleke FN, Hasan QM, Epe SB, Emodi NV. Multidisciplinary Composition of Climate Change Commissions: Transnational Trends and Expert Perspectives. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410280

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbraham-Dukuma, Magnus C., Michael O. Dioha, Natalia Bogado, Hemen Mark Butu, Francis N. Okpaleke, Qaraman M. Hasan, Shari Babajide Epe, and Nnaemeka Vincent Emodi. 2020. "Multidisciplinary Composition of Climate Change Commissions: Transnational Trends and Expert Perspectives" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410280