1. Introduction

There has been abundant literature produced on urban resilience over the past few decades, particularly in the areas of environmental science and urban planning. Currently, the mainstream theories and discourses of technical managerialism inform and are informed by standardized, universal guidelines directing the ways in which global societies perceive and respond to climate change. From the Kyoto Protocol to the Paris Agreement, the consensus established in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) symbolizes a shift towards postpolitical regulatory regimes, in which concerns about local politics and public participation have become less salient than common interests in implementing resilience-oriented planning strategies and design techniques. Nevertheless, urban resilience encompasses not only keeping the physical environment durable in the face of natural or human-induced risks and disasters but also the involvement of a diverse population and different communities in decision-making mechanisms for pursuing urban sustainability. As part of this special issue, “Planning Resilient Community: Public Participation and Governance”, this article aims to provide theoretical insights into the socioecological systems behind the practices and policies of planning for urban resilience, informing institutional approaches for engaging societies in municipality-led integrative mechanisms for sustainable development.

Indeed, any innovative strategy for urban resilience needs to tackle the goal of incorporating local wisdom into integrative mechanisms. What kind of “integrative mechanism” is desired in creating cities of “just sustainabilities” [

1] instead of cities planned with only universal knowledge and gold standards in mind? To what extent and under what circumstances can the local state engage civil society in institutional reforms so that non-governmental organizations (NGOs), community coalitions, local businesses and city officials can benefit from one another’s viewpoints in planning resilient communities without regularly confronting grassroots resistance or even large civic rivalry? In other words, it is crucial to investigate the complexity underlying bureaucratic behaviors, managerial regimes, and intersystem coordination in relation to the shaping of local politics and reshaping of policy mechanisms and institutional frameworks of urban resilience. To this end, this paper reviews urban political ecology (UPE) as a critical theory for investigating the significance of socioecological multiplicity and its influence on shaping a resilient city. This article examines a critical debate on the ways in which UPE can be provincialized and situated to be more sensitive to the nuances in local governance in the cities of the Global South. Furthermore, it compares two different strands of research that both aim to provincialize UPE: one is postcolonial urban theory, and the other is an ecological political economy that applies the strategic-relational approach (SRA) to UPE. The conclusion comments on the strength of an integrative framework that combines UPE and the SRA, reiterating the critical role of the local state in municipality-led programs to build urban resilience.

2. Urban Political Ecology and Its Paradigm Shift

Political ecology emerged in the 1980s as a theoretical paradigm examining the issue of environmental deterioration resulting from the exploitation of nature due to industrialization and the underlying condition of social inequality as a result of rapid yet unbalanced economic development. It began as a type of structuralist ethnography analyzing the power, knowledge, and discourse of the environment; the issues of modernization and development are its analytic foci [

2,

3,

4]. There has always been a common research agenda among political ecologists and Marxist geographers in their queries of citizens’ unequal rights to land, resources, and ecologies in the face of capitalist economies.

During the 1990s, political ecology began to incorporate poststructuralism to explore the diffuse forms of power. Meanwhile, political ecology started to detach from eco-Marxism that focuses on the social production of nature [

5,

6]. However, by 2000, poststructuralist political ecology and eco-Marxism had become largely integrated [

7]; therefore, political ecology draws on the merits of both poststructuralism and political economy [

8,

9]. As the theoretical framework became enriched by the two paradigms, the topics also became more diverse, incorporating topics such as ecosystem services, air pollution, and climate change [

10,

11]. Geographically speaking, political ecology has since been extended from the Global South to regions in the Global North. However, the field research settings remain primarily rural areas at this stage [

12].

Towards the end of the 1990s, scholars started shifting their interrogation of the interrelationship of capital, society and nature in the rural environment to that in the urban milieu. In doing so, they developed urban political ecology, which delves into the dialectic relationship between society and nature, shaping and reshaping cities. Unlike political ecology, with its varied theoretical roots, UPE is a direct descendant of Marxist geographical theories. Such a theoretical perspective questions the power relationship embedded in the natural environment as well as in human’s social nature. The task of UPE is therefore twofold—it examines the biophysical aspects of the built environment, but it also critically tackles the capitalist quality of the seemingly natural environment. On the one hand, this perspective suggests that nature shapes the city through an exertion of power relations over capital accumulation. The benefits of natural resources and networked infrastructures are often unequally distributed and shared among citizens of different socioeconomic classes [

12]. Urban infrastructures, such as water sewage, electricity networks, and riverbanks, are all environmental hybrids shaped by power and capital [

13,

14,

15,

16]. During this period, UPE departed significantly from political ecology by focusing on urban space and landscapes rather than on rural environments and resources. The common agenda pursued in various empirical cases is exploring the way in which nature, through various policy initiatives, planning strategies, and governance schemes, catalyzes capital accumulation for urban development and economic growth. In sum, UPE incorporates constructivism into its Eco-Marxist framework by emphasizing the ways in which the city mediates the social production of nature through urban policies and environmental discourses. Some of the key terms, such as hybrid nature, socioecological assemblage, cyborg urbanization [

17,

18] no longer distinguish between first nature and second nature, but instead recognize the fluidity and compound feature inherent to socionatures. Scholars then extended these notions into the scope of analyzing the process driven by the material flow of society-nature exchange, that is, the theory of “urban metabolism” [

18,

19]. Discourses of urban metabolism have adopted Deleuze and Guattari’s [

20] assemblage theory, informed by actor-network theory [

21], to study the rhizomic networks constituted by actors and actants. This body of work formed the first wave of UPE.

The second wave of UPE went on to strengthen its actor-network perspectives to dilute Marxist ontological approaches while engaging a methodological adjustment blurring a looming urban–rural boundary in the first wave [

21]. UPE in this phase has more formally incorporated posthumanism into interrogating a world composed of human and nonhuman entities to enrich its social constructivist analysis and to correct “an overly deterministic emphasis on the production and meaning of urban nature” ([

22], p. 601). Nevertheless, this body of UPE literature stands in contrast to assemblage urbanism, grounded in the sociology of technology and science, which continues the tradition of poststructuralism (see, for example, [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].) However, these two paradigms later become partially integrated, even though some of their respective advocates were determined to criticize their counterparts’ viewpoints [

31,

32]. The difference is that UPE has found its roots in Marxism, Actor-Network Theory (ANT), and posthumanism consecutively, while assemblage urbanism has completely rejected both Marxism and any presumed social structure. For instance, Brenner, Madden, and Wachsmuth [

31] argued that “UPE applies selected logics from ANT to build upon and reformulate the treatment of socionatures within critical urban political economy” (p. 232), unlike the ANT-based assemblage urbanism that insists on depoliticizing urban studies by treating all kinds of materiality and actors symmetrically in its posthumanist analysis of cities.

A call for moving beyond cityism in UPE marks another contribution of the second wave. Angelo and Wachsmuth criticized the first wave of UPE for its “methodological cityism”, suggesting that it limits the analysis of urban metabolism within only “cities” [

33]. Brenner echoes this critique by examining the meaning of “operational landscapes” appearing on the hinterlands outside cities [

34]. He borrows Lefebvre’s notion of planetary urbanization to redefine contemporary urbanization as a spatial representation of global capitalism instead of a process of social agglomeration [

34]. The second wave of UPE, therefore, has moved beyond interrogating urbanization as a dynamic, networked, and extensive phenomenon, extending into new realms of theorizing the urban–rural nexus [

33,

35].

3. Advocating a Provincialized UPE from Postcolonial Urbanists and Southern Theorists

Urban political ecology overall considers capitalism to be the major force driving urban metabolism [

36]. UPE prioritizes the influence of capitalism itself over the influence of other factors, such as those of the diffuse forms of power, heterogeneity in governance, everyday practice and grassroots resistance. Additionally, most UPE empirical cases have been conducted in the Global North, making some question the Eurocentrism underlying the UPE framework. As such, postcolonial scholars have advocated a “provincialized UPE” or a “situated UPE”, which means that UPE should engage more cases from countries in the Global South to avoid universalism as well as economic determinism in UPE. (This article acknowledges variability in neo-Marxism or political economy as many sub-theories have extended, modified, or enriched Marxism in varied ways, giving more nuances among different arguments in critical urban theory. Therefore, this article uses “economic determinism” or similar terms with no intentions of homogenizing the contributions of either UPE, or urban political economy, but rather, to highlight and to question one of the major roots of their analytic vectors.) Rejecting the idea that a pre-existing political-economic structure determines singular urban transformation patterns, postcolonial theories emphasize such concepts as environment, knowledge, and power and the ways these analytic components can influence the development of urban change [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The term “provincialize” is a major critique that postcolonial scholars adopt to criticize political economy, as it tends to universalize, totalize, and eventually homogenize urban experiences in various geopolitical contexts. From critics’ perspectives, political economy is less concerned with local variation than with identifying the general logic of capitalism.

By incorporating posthumanist thinking, urban political ecology has developed a sophisticated analysis of human and nonhuman relationships. Meanwhile, UPE has started looking beyond business elites but paying attention to a variety of actors involved in urban governance. Postcolonial scholars deliberately draw on knowledge from southern urbanism in an attempt to yield conceptual vectors based on various parts of the Global South. As Lawhon, Ernstson and Silver argued, “this frames the ‘global South’ as an epistemological location—rather than a geographical container—through which a provincialization of dominating theory can be crafted” ([

7], p. 505). In order to avoid homogenizing and oversimplifying their findings, which are based on different field locations, scholars argue that UPE needs to become provincialized, and they have explained this in the following way:

To provincialize UPE is to develop a way of framing that is more attentive to place and that can question taken-for-granted ideas in order to broaden the scope for theorizing with more urban experiences in mind. We refer to the outcome of this provincialization as a situated UPE.

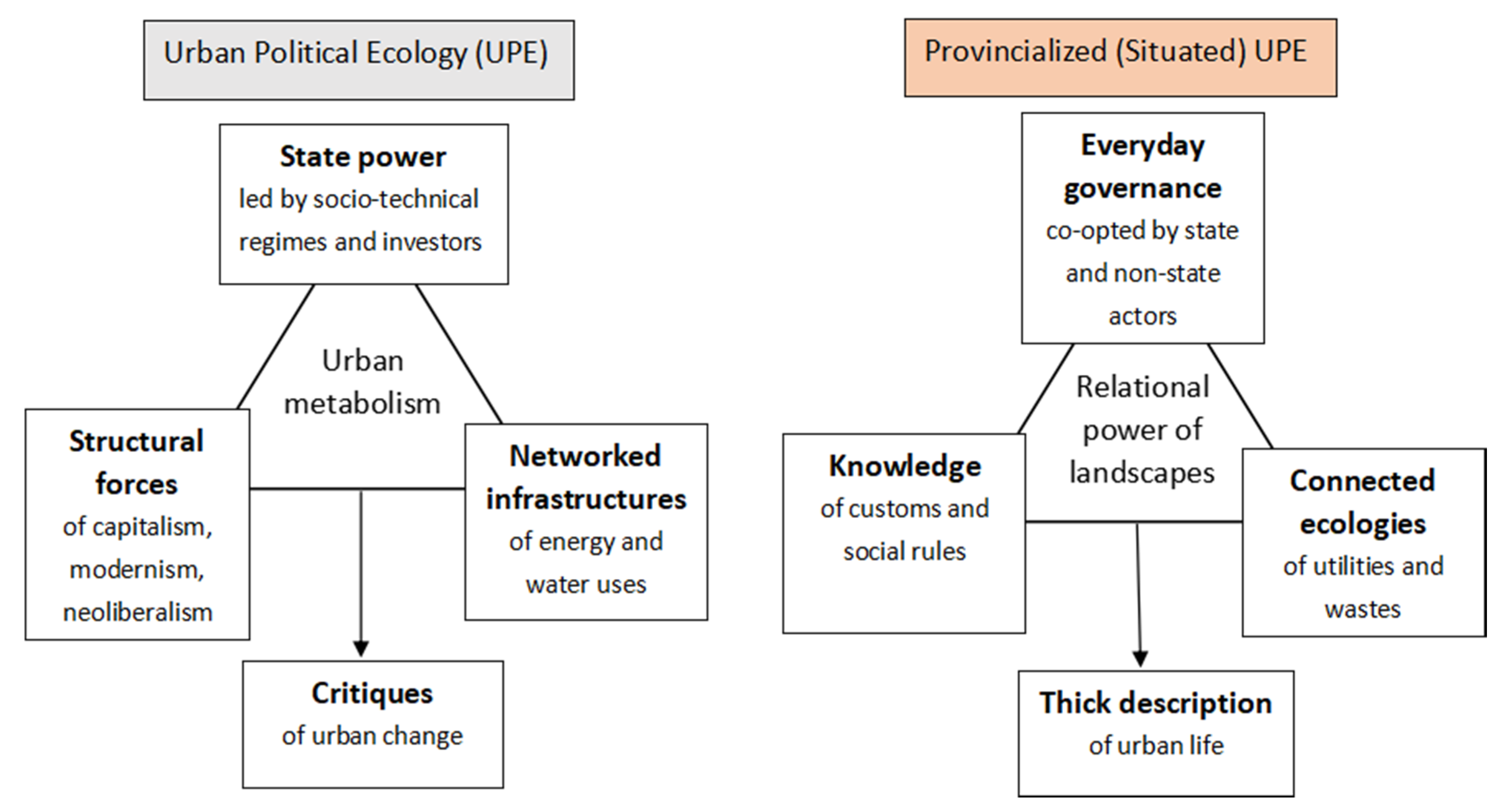

A group of postcolonial geographers have rhetorically unpacked provincialized UPE. To compare the conceptual vectors of (Marxist) UPE, as opposed to situated UPE, Lawhon et al. identified three dimensions of each framework. UPE firmly believes in the existence of an economic structure dominating any progression of urban metabolism in the form of material flow and socioecological exchanges. Both physical and abstract exchanges are channeled through urban infrastructure providing water, electricity, transportation services, and so on, as seen in most highly urbanized settings. These are scenarios in which “large actors” such as municipal officials and corporate investors collaborate on mega urban infrastructures that reshape urban ecologies appear to be universal [

43], and this formula of urban development often seems uncontested, albeit largely questioned in UPE, and it meets with only a little resistance in reality. This means that UPE’s main critiques remain consistently and conveniently subjects such as capitalism, modernism, and neoliberalism [

7].

Situated UPE, on the other hand, considers powers as distributed, situated, and often relational and holds that “this is complemented by a variety of logics, intentionality and assemblages of the non-state, non-elite majority” ([

7], p. 507). The everyday practices of various scales of community units and events thus play a larger role in city making than state-led projects do. Instead of taking Marxism as a framework for its theoretical construction, situated UPE questions the logic of city-making by contextualizing its arguments based upon on-site observations and the interpretation of incremental changes. For example, Truelove [

42] examined social and political power from the non-state political actors and residents operating in accordance to and in relation to the bureaucracies. As such, it is the combination of the state and non-state actors that constitutes the hybrid networks of “everyday infrastructural governance”. On top of a decentered notion of power and governance, postcolonial scholars also advocate a consideration of ecological connections between networked infrastructures and fragmented, scattered sources of utilities (see, for example, water supply in Jakarta, [

37]). What is common in postcolonial, or situated UPE is their theoretical reorientation towards a more heterogeneous and relational urban political ecology, one that offers situated critiques of city making [

7], instead of the critiques of capitalism or neoliberalism.

In fact, postcolonial theory argues that the growth trajectory of cities in the Global South is a nonlinear process, often contradictory to what some Marxist theorists predict. This is because local governments in the Global South tend to negotiate various interests in their search for a balance between citizens’ livelihoods and corporate interests. Additionally, citizens sometimes build social infrastructures by mobilizing their social network to gain access to essential resources, such as water, energy and electricity, rather than solely depending on the local state to provide such necessities [

44,

45]; therefore, the provision of infrastructure does not necessarily follow the paths of privatization, corporatization, and commodification, as seen in the context of the Global North. In other words, there is a wider social hierarchy shaped by diffuse but connected power relationships among various power exercisers, not by social elites and the upper classes demarcated by capitalism [

44,

46]. If we acknowledge this fact, we can conceptualize the local politics in cities in the Global South, compared to those in cities in the Global North, as a more complex, heterogenous system of “assemblage governance” in which local state policies engage deeply with both formal and informal ruling systems and grassroots ideas. This political climate makes it more challenging for both domestic and international corporations, capitalists and investors to profit in developing countries than in developed ones [

47].

There are essential differences between the research agendas of UPE and situated UPE that deserve closer attention. UPE aims to yield theoretically informed critiques of urban change, while situated UPE is inclined to depict urban life in place-specific contexts (

Figure 1). Nevertheless, this promise of provincialized UPE and the critiques of socioecological change are not necessarily mutually exclusive. To name a few, some of the recent studies have linked both the voices of the community and the local state to a centralized ecological regime though their grounded, field research that well informs both social resilience and local governance. For instance, in their study of a wetland of Xochimilco in Mexico City, Eakin and Manuel-Navarrete [

48] find residents’ and city administrators’ experience of losses of livelihood and place identity as a salient response to socioecological change produced by the municipal policies of land and water uses. Their work recognizes the power of a local state apparatus restructuring natural landscapes, while valuing the significance of community members’ resilience in negotiating socioecological change. Linking social constructivism to political economy, Moore situates ecological crisis of capitalism in the historically formed human–environment relationship, tracing the origin of the crises back to centuries ago, way earlier than the era of industrialization [

49].

4. Capitalism as a Set of Institutionalized Forces?

Based on experiences in the Global South, another group of scholars specializing in Asia tends to adhere to the framework of political economy in exploring urban development. For example, the studies on the modernization of Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea see a clear path of East Asian capitalism explaining these regions’ rapid industrialization under state-led development projects. In fact, the growth of previous Asian Tigers or ASEAN countries now reflects the argument of some Western-trained scholars that neoliberalism is path-dependent and flexible in policy implementation (see, for example, [

50,

51]); critics assume that capitalism has the same resilience in adapting to various geopolitical contexts, often morphing into new forms in order to compromise the local political climate, social reality and historical contingency. These critics suggest that capitalism is never a “one scheme fits all” model; rather, it is meant to evolve over time and acts in repose to various geopolitical contexts. However, Marxists believe that capitalism presents certain common patterns in its influence on different societies even when it presents place-based variation and flexibility in actual practice [

52].

The debates over whether political economy or postcolonial theory is more applicable to urban issues remain heated, and the decision about which theory to adopt may indeed depend on the choice of topic. The “hottest” topic in the Global North cities has predominantly been infrastructure, which involves the provision of utilities such as electricity and water. As these material flows fundamentally support human life and the functions of the urban environment, their provision is more likely to be commodified and thus easily enters the cycle of urban metabolism in UPE. In contrast, research on Indian and African cities is more interested in the “lack” of infrastructure and the ways citizens cope with such a shortage to maintain their livelihoods [

21]. For example, lacking waste-processing systems on individual properties, Indian citizens utilize the river as an alternative to public toilets [

45]. Even in the West, developers investing in natural resources do not necessarily profit from the need of the public or the private for them. In neighborhoods where communities are evicted or displaced because of rezoning initiatives that aim to replace residential property with green space, parks or greenery become green locally unwanted land uses (LULUs) [

53,

54]. As such, the role of local government is crucial in UPE, and the significance of local politics is indeed largely neglected in the current UPE framework, a major problem that southern theorists have attempted to correct through “provincializing UPE”.

Nevertheless, the omission of capitalism as an institutional force creates another problem for studying Asian cities, where the built environment is largely being reshaped by real estate markets. State-led urban renewal, slum clearance, and infrastructure upgrading have all clear goals of boosting the real estate market to benefit poverty owners and developers, which typically come at the price of unjust land speculation and the social exclusion of the disadvantaged. However, understanding the extent to which a local government can strike a balance between economy and equality and in exactly which ways the local state can show more nuances in municipality-led urban agendas indeed requires additional theories that politicize UPE, that is, to “bring the state back in”, as such theorists have suggested. In other words, it is essentially a capitalist state with its major collaborators that direct urban change; yet, this jointly created state power is intertwined with the secondary influences from a set of formal and informal power holders, such as those from the land proprietors, borough leaders, local politicians, and the media. Therefore, we would need a more relational analysis of state power ruling the democratic societies. Besides, the theory of situated UPE in its current form has not analyzed the ecological reconfiguration of the built and natural environments by the human and non-human actants as relationally as the theory treats the practice, action, and power shaping such configurations. Exactly what makes situated UPE a subset of postcolonial urban theory, or what is “ecological” about situated UPE, is by far unclear (see [

37] for one of the few exceptions). In fact, a similar group of analytic vectors exists in both situated UPE and the early political ecology, leaving the choice of field settings in the two theoretical paradigms to be their only distinct difference.

Now it is time to take the question slightly further—is there an alternative way to provincialize UPE other than what has been offered by postcolonial theory? Since Asian capitalism is not imagined, finding alternative ways to address it properly is crucial. In what ways can we provide a grounded yet critical analysis of urban ecologies without losing sight of the forces of capitalism mobilizing sustainable city making? In the following, I will introduce a few theories that are appropriate for examining the local state and related empirical works. The ways the state theories contribute to UPE can shed light on the path towards situated UPE, one that considers diffuse power relationships embedded in sustainability politics, as well as the influence of green capitalism.

5. An Alternative Approach to Provincializing UPE: Applying the Strategic-Relational Approach (SRA) to UPE

Stone [

55] developed the term urban regime to describe the informal arrangement established between a local government and business elites that forms a system that can govern urban affairs more effectively than the government alone. The reasons for this efficacy lie in the fact that the urban regime is based on trust and mutual understanding, yielding a flexible yet pragmatic governing strategy. The idea of the urban regime supports the social construction of governance. This suggests that no urban policy has a predetermined structure influencing state decisions but does have a public–private coordinating mechanism subject to contingent changes, well-established customs and ongoing relations between the actors taking part in the plan. Capitalism, or neoliberalism, is therefore a far-flung yet indefinite structural force of urban development. It is truly an urban regime that exercises immediate influence over policy implementation, shaping the optimal outcomes that may elicit the least contestation.

Similarly, Bob Jessop suggested the strategic-relational approach (SRA) as a theoretical lens for analyzing the behaviors of the modern state. Unlike the urban regime, which highlights the balanced action of the state and businesses, the SRA focuses on the state’s strategic thinking while paying more attention to both capitalism and resilience against capitalism in influencing state decisions [

56,

57,

58]. One can find evidences for social constructivism in neo-Marxism in one of its classics, Molotch’s “The city as a growth machine” [

59], in which he holds that city officials, developers, the media, and financial services constitute a growth coalition as the key agent responsible for property-led urban growth. An anti-growth coalition, made of residents, environmentalists, and pro-poor NGOs, tend to contest a growth regime by accentuating the use values of property and the local community’s attachment to the neighborhoods. And yet, this binary category neglects the state’s agency of shifting its roles to ensure both harmony and success in urban development.

As an alternative, the SRA acknowledges both historical materialism and social constructivism in neo-Marxism, and it adds complexity to the framing of them. Specifically speaking, the real state is a system of social relations capable of mediating between the positive and the negative forces for the successful implementation of policy initiatives. As such, Jessop suggested the importance of the role of “strategic selectivity”, as opposed to institutional structures such as capitalism or socialism. Strategic selectivity is an institutional field constructed by the state but co-opted by multiple actors in the hope of balancing different forces for the making of optimal decisions for both the public and private sectors, and most of all, for the state itself. However, Jessop emphasizes the fact that strategic selectivity is driven by a variety of power holders, which makes the formation of strategic selectivity a highly contested procedure [

60]. Therefore, the SRA modifies economic determinism in neo-Marxism by arguing that state power cannot be reduced to class-based hegemony. Rather, the foundation of state power is a contested institutional field (ibid.).

There are three primary contributions that the SRA can bring to the study of the local governance of environmental issues. First, the SRA politicizes UPE while resonating with its inherent economic focus. Second, the SRA reveals that a state apparatus is not a preexisting entity but is socially constructed by multiple actors as they exercise individual power in their constant negotiation and communication with one another. They do so in order to compromise when making decisions or to resolve their differences. Therefore, a state apparatus is an ultimate representation of balanced forces among the actors participating in a strategic game [

56]. When discussing the forces, the SRA covers the forces deployed within an institution as well as the exterior and interinstitutional forces. Therefore, the SRA captures the dynamics and complicated networks existing among the government, private groups, and civil societies, exploring the interrelationship among different sectors within and outside any political institution. This feature makes the SRA a more thoughtful theoretical lens than the urban regime concept. Third, recent SRA studies have linked the concepts of politics and social relationships to environmental research. For example, Quastel [

61] characterized environmental studies utilizing the SRA as a unique type of “ecological political economy.” This shows that the employment of the SRA in ecological studies is an emerging trend and a legacy of political economy.

The SRA has been widely applied to empirical studies of the environment and resources, and it is specifically linked to UPE in some cases by analyzing the ways in which the state mediates the interaction between nature (ecologies, resources) and society (civil society and industries). As examined in a group of case studies on green economies, there have been both successful cases of state mediation and failing cases. Adopting the SRA to a study of the privatization of the oil sector in Mexico, Heigl [

62] found that the interaction of actor strategies and governmental institutes enables alternative historical paths beyond a post-Fordist accumulation regime. Despite being considered a neoliberal public institution in Mexico, the Ministry of Finance in Mexico demonstrates decisive resistance against oil sector privatization. Ioris [

60] incorporated the SRA into the UPE of the water management problem in an area in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil: Threatened by multiple problems imposed by having a precarious water supply, regular flooding and severe river degradation, state interventions favoring selected groups and areas only strengthen the politicization of water management. In South Korea, the path dependency of the state-driven water resource policy under the former authoritarian regime persists even after democratization, making it difficult for the government in power to transform pre-existing authoritarian and hierarchical water governance into newly democratic and environmentally friendly governance [

63].

Theoretically, the SRA is also compatible with UPE, as the two theories share assemblage thinking (

Figure 2). The SRA suggests that any state, government, or governing entity is an assemblage in itself. As Jessop [

58] frames it, “state projects may originate outside a given state (e.g., through intellectuals allied to different social forces), may be elaborated within (parts of) the state apparatus, or may be copied from elsewhere or imposed by external forces. Enduring projects are usually embedded in a constitutional settlement or institutionalized compromise” (p. 85). In addition to the role of formal institutions, the SRA emphasizes the existence of an informal arrangement of governance: “Indeed, the bureaucratic preconditions for the formal unity of the state system may limit the substantive efficacy of policies oriented to accumulation, legitimacy, and social cohesion. This is reflected in the coexistence of formal bureaucracy governed by clear procedures and more informal, flexible, or ad hoc modes of intervention. ([

58], p. 68)”. The SRA analyzes the behaviors and attitudes of a government institution by considering not only inputs but also outputs and with inputs existing both between institutions and among agents.

In terms of the idea of political support in a democratic regime, Jessop [

58] has made such a claim:

In modern states such political support is not reducible to ‘consensus’ but depends on specific modes of mass integration (or indeed exclusion) that channel, transform, and prioritize demands and manage the flow of material concessions necessary to maintain the underlying ‘unstable equilibrium of compromise’. Nor does it exclude conflict over specific policies, as long as this occurs within an agreed institutional framework and an accepted ‘policy paradigm’, which establishes the parameters of political choice. Social bases are heterogeneous and different social forces vary in their commitment to the state in different conjunctures.

(p. 72)

The abovementioned quotes make the SRA particularly applicable to democratic politics influenced by different local elections. As such, it properly grounds the economic influence on the sociopolitical mechanism. In doing so, it builds up a hierarchical analysis of any regime by diversifying the power relations rather than depicting a flat analysis of the regime without distinguishing the spectrum in power variations among those actors. That kind of flat analysis is explicit in urban regime theory, as it emphasizes a political balance established between the local state and the business community, whereas that balance is always destabilized, contested and thus subject to politicization.

6. Conclusions

Both the urban regime and the SRA approach the nuances in local governance. Both concepts, when combined with UPE, can enrich the political analysis of the green economy, sustainable development, and changing landscapes. If the rationales for and promises of advocating for provincialized UPE are searching for a refined framework capable of uncovering the diffuse forms of power deployed within the modern green economy and making UPE more sensitive to different geopolitical contexts, the strength of the SRA can justify itself as a strong addition to UPE. The SRA alone, however, does not contribute well enough to the study of sustainable development, as the SRA as a theory lacks spatial dimensions and an urban focus. Combining the SRA with UPE therefore makes a framework that is more concrete for the following reasons.

First, one of UPE’s major concepts is “socioecological assemblage”, which not only applies to the urban environment but also tackles the multiplicity and heterogeneity in the formation of initiatives, systems and people who contribute to urban resilience. The concept places human and nonhuman systems in a balanced position so the two systems’ mutual influence and interactions become thoroughly pronounced. By incorporating the SRA, UPE builds a holistic network of all these actors and actants without losing political insight into the strategic thinking behind all of the network building. Furthermore, the integrative framework brings the public–private relationship to the font line. In doing so, this provincialized UPE approaches the notion of a “resilient community” by simultaneously analyzing the aspects of public participation and governance, that is, the actions and mindsets pertaining to civic society and the local government, respectively. For practical implications, the community can then contribute to strengthening urban resilience by cooperating with both established institutions and self-organized coalitions in a way that allows civic voices to be heard and the communities’ needs to be addressed.

Second, the theory examines the critical role of the state. On the levels of policy making and professional practice, there has been an increasing demand that local government be taken into fuller consideration in planning for sustainable development. In achieving sustainable development, the UN New Urban Agenda specifically identifies local economy, municipal finance and local implementation as three dimensions that are equally important to the other national and urban level principles and standards [

64]. The actors involved in the local governance of sustainability have therefore been expanded to include “civil society organizations, the private sector, and constituent groups” ([

65], p. iv), in addition to municipal officials and political leaders. Applying the SRA to UPE responds theoretically to the New Urban Agenda’s paradigm shift, which values the important role of the municipality as the integrative analysis lays out a framework to study urban resilience, which requires abundant efforts by local states. This social constructivist framework of the SRA allows for the academic and the practitioner to brainstorm policy innovations that are adaptive to the unique features and institutional frameworks of local politics.

Last but not least, UPE critically examines the forces, process and effects of urbanization driven by the power of the social production of nature. A holistic framework applying SRA to UPE, then, helps promote the strategies of operationalization in addition to the critiques of neoliberal urbanization. On the one hand, UPE explains the ways in which urbanization impacts the three pillars of sustainability. On the other hand, it questions whether the city as a symbol of socioecological assemblage can allow solutions, interventions, and opportunities for overcoming climate change to emerge. In other words, any innovative approaches to a socially just and ecologically friendly city must start from a world of human and nonhuman assemblages. The changes of achieving this goal lie on the degree to which a regime of strategic selectivity can balance conflicting, yet relational interests of various stakeholders in order to implement a series of pragmatic solutions in terms of the discourses, the policy initiatives, and the actual programs (

Figure 2). Be it an eco-city master plan, or a set of green building design guidelines, a solution representative of a socioecological assemblage is always situated, destabilized, and then stabilized in a web of sociopolitical power relationships within a specific geopolitical context for “an engaged pluralism” [

65], advocated by critical urban theory today.

This perspective on urbanization not only resonates with the UN New Urban Agenda but also fits the essential spirits of urban resilience discourses. The nature of urban resilience as a concept suggests that urbanization, as an inevitable process, needs to be accompanied by possibilities for balancing the growth of a city with ideal environmental qualities. Urban resilience therefore does not condemn urbanization or aim to slow planetary urbanization down; rather, it supports urbanization if, and only if, different parts of the planet are to be urbanized with mostly green infrastructures and low-impact building strategies. However, the underlying technical managerialism often minimizes, if not denies, the social exclusion and uneven development incurred by “ecological gentrification” [

66], namely, the social exclusion caused by rising property values following state-led infrastructure upgrades, such as the construction of urban parks, waterfront areas, and public transit. UPE aims to uncover the issues of social inequality and land justice in order for us to rethink and reevaluate all of the social impacts of policy initiatives and programs in the name of urban resilience. Only by including the voices of a wide variety of actors and power holders within communities as well as in civil societies can we truly expect innovation to cultivate the capacity of social resilience in governance and policy implementation.