1. Introduction

Attention to students enrolled in schools must set out from the basis of inclusive education to be able to meet all educational needs. This involves structural, organizational, and methodological changes… and leads us to the conviction that the educational system is responsible for educating everyone [

1]. In turn, Ainscow [

2] advocates for educational inclusion to respond to the right to quality education. For inclusive education to exist, it is important to promote the idea that these three factors must intervene satisfactorily: presence, academic performance, and participation. On the other hand, Echeita [

3] (p. 17) warns that the school is faced with “the challenge of attempting to ensure educational equity, a necessary condition to achieve a school education that is more inclusive.”

For more inclusive education to be achieved, it is necessary for all educational agents to be involved in the new school culture.

It must be taken into account that according to data collected from the reports of the Ministry of Education [

4], foreign students in non-university education constitute almost 10% (9.9) of the total student population, a figure that increased last year by 8.6% (the highest increase since the 2016–2017 academic year), with the highest concentration in state schools. To understand the reality of immigrant pupils in our schools, it is necessary to know what the most common difficulties are that arise and what actions are taken in the classroom to alleviate them by the teachers. The most common difficulties are usually that these students do not share the cultural values of the context in which they are inserted; they do not always have the same language, which hinders their learning; and they tend to have educational needs derived from situations of inequality in the social and economic spheres [

5]. For their part, teachers, apart from temporary classrooms (a specific resource for this group), and especially in the secondary education stage, do not apply an intercultural education model, but rather a compensatory education model [

6]. Both issues lead to failures and early school dropouts.

Based on this reality and to provide an answer, one of the aspects that needs to be updated and promoted is training in intercultural education. In particular, there should be more specific training for practicing teachers [

7,

8,

9], as well as for university students on education-related degree courses and receiving initial training, as “in the majority (63%) of study plans or curricula there are no specific modules that deal with the issue of cultural diversity” [

10] (p. 119). In this line, [

11] emphasize that an effective connection between the initial training of students in the primary education degree course and the multicultural reality of the classrooms in today’s society is essential. As stated above, although it is important for teachers to acquire a level of training in the management of cultural diversity, the response received by immigrant students from educational administrations is also very significant. To this end, we highlight as the main resource or device the special Spanish learning classroom for immigrant students recently incorporated into the Spanish educational system, which goes by different names throughout Spain and its autonomous regions. In the case of Andalusia, the so-called Temporary Classrooms for Linguistic Adaptation (hereinafter ATALs) have been up and running for over a decade, taking in pupils who do not know or have difficulties with Spanish: up to a maximum of 10 h per week in primary, from the second cycle, and up to a maximum of 15 in secondary [

12] (p. 71). On one hand, “ATALs are an educational resource of the Ministry of Education of the Junta de Andalucía, managed by its provincial delegations, whose teachers are part of compensatory education, in some cases incorporated into the Educational Guidance Teams or school staff” [

13] (p. 3). For [

14] they are “special classrooms,” in most cases separated from the “ordinary” classes, in which foreign or immigrant newcomers with little or no Spanish receive support for their incorporation into the school.

Considering the regulations that govern it, the Order of 15 January 2007 [

15], the ATALs are “programmes for the teaching and learning of Spanish as a vehicular language, linked to specific teachers, which allow the integration of immigrant pupils in the school and their incorporation into the rhythms and learning activities of the level at which they are enrolled, taking into account their age and curricular competence.” Their main functions include the provision of inclusive support, i.e., within the ordinary classroom, except when the level of knowledge of the language discourages it.

In any case, this support should not last more than two academic years. ATALs have their own teachers (in some places, colloquially, “intercultural teachers”), whose primary function is teaching the language, but also the school inclusion of foreign pupils in collaboration with conventional teachers.

Along these lines, numerous studies and research works have been carried out in the Andalusian scope [

12,

14,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], which mainly tackle the following topics: creation, system, operation, and evolution of ATALs; reception of students of immigrant origin; and ATAL language teaching and teacher training. The majority of these research works have been carried out mainly based on the beliefs, attitudes, and actions of the ATAL teaching staff [

14,

15,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Hence, it is important to note that ATAL teachers become a decisive agent in direct educational care and monitoring of immigrant pupils with deficiencies in the knowledge of Spanish as a vehicular language in the teaching–learning process.

ATAL teachers work alongside the team of tutors and the rest of the teaching staff, but they mostly collaborate and coordinate with the counselor and the special education teacher [

45] to such an extent that the ATALs have been considered within compensatory education with the main objective of compensating for socio-cultural and context inequalities [

17,

20,

27,

34,

37,

46,

47].

The need remains to further document the relationships and collaborations with the school counselor and, therefore, the role they play in managing diversity and promoting intercultural education. The work and roles of counselors [

48,

49,

50] have been undergoing changes in recent years following the demands from teachers and schools and, ultimately, in response to the great challenges of the society in which we live.

In general, we detect that “the functions most carried out by counselors are those included in counseling and consultation, followed by guidance, evaluation and coordination; few mediation functions are carried out, the follow-up being almost non-existent” [

51] (p. 36). In this way, the school counselor assigned to the Educational Guidance Teams, in early childhood and primary education and in the guidance departments in secondary education, takes on a lesser role than that described in previous studies in terms of ATAL operation.

Related to the above, we find works whose main objective is to discover the opinion of counselors about how attention to diversity is articulated in public secondary schools [

45,

52,

53], and for this purpose they have designed an instrument that helps identify the measures in attention to diversity in each of the contexts analyzed [

54,

55].

In this line, interesting contributions are compiled on the role of the school counselor in their task of advising immigrant students, charged with promoting knowledge of culture and being responsible for multicultural processes [

52,

56,

57]. However, other studies highlight the lack of training and intercultural skills in school counselors [

58].

Likewise, the school counselor, in addition to advising the pupils at an academic and professional level, must also encourage coexistence in the school, promote intercultural relations, and accompany the students in their personal development processes [

59]. In this line, an essential part of the counselor’s job consists of helping students face social, psychological, linguistic, and academic difficulties they might encounter in their process of cultural adjustment and family reorganization. In this line, an essential part of the counselor’s job consists of attending to the social, psychological, linguistic, and academic difficulties that students may encounter in their process of cultural adjustment and family reorganization [

60].

In Spain, it is still necessary to increase the output in this line of work, although we found some important contributions, for example, on the emotional competencies of the school counselor when working under the aegis of inclusive education [

61].

In connection with the previous idea about the roles of school counselors as managers of cultural diversity, in these lines we take as a theoretical grounding the basic models of psychopedagogical orientation distinguished by [

62] a clinical model of individualized care, the program model, and the consultation model, in each of which the functions and roles of the counselor have their own characteristics, to put forward the idea of the “emergence of other collaborative work models strongly incorporating the role of support and advice to teachers into the counselor’s profile” [

63] (p. 41). Thus, this model makes the counselor’s intervention with the student not so direct but rather through the teaching staff. This way, the counselor–teacher binomial becomes stronger and the work is carried out in a linked-up manner, so that the counselor provides the teacher with tools and strategies to intervene with their pupils. There is no doubt that the counselor also intervenes directly with the diversity service pupils [

64,

65] in psychopedagogical diagnosis and evaluation, reception of foreign students, orientation, and tutoring, etc. In relation to this, if we analyze the guidance models that are endorsed in counseling practice, we find studies that emphasize the dominant use of a clinical intervention model with isolated and specific collaborations with teachers and other educational agents (managers, educators, social workers, families) and firmly focusing on intervention-based guidance models that are more alternative and participatory with which to better manage cultural diversity [

45].

Finally, as an important aspect, we examine the counselor’s work in the field of application, organizational aspects, operation, monitoring of foreign pupils, and organizing of the ATAL teaching staff. Counselors’ role is key for the promotion of change in schools; their work is essential to helping schools manage cultural diversity, interculturality, and inclusion in the best possible conditions. The role that these professionals play is key to promoting change and enabling schools to be in the best conditions to manage cultural diversity [

66] and because of that, play an essential role in matters related to interculturality, inclusion, and diversity [

67,

68].

As analyzed in the Order of 15 January 2007 of the Junta de Andalucía [

15], counselors, through the Provincial Technical Educational and Professional Guidance Teams, play a very important role in the measures and actions developed for the care of immigrant students and especially Temporary Language Adaptation Classrooms. In this sense, we summarize articles 1, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 12 of this Order, in which aspects of the advice that these professionals provide to schools are compiled: attending tutoring meetings with the tutor; offering advice to the Head of Studies and ATAL staff on the detection, reception, and psychopedagogical and curricular evaluation and to faculty to indicate the possibilities of immigrant pupils taking part in specific programs; participating in decision-making regarding the continuity or not of immigrant students; coordinating the teaching staff of the Temporary Language Adaptation Classrooms in each province; collaborating in development of the teaching staff of the Temporary Language Adaptation Classrooms of each school; having knowledge of the classroom programming developed by the ATAL teachers.

In short, the counselor is a key part in the operation, organization, monitoring, and evaluation of the ATALs, immersed in all the tasks related to the reception of immigrant pupils, organizing their work with the corresponding tutor, coordinating with the ATAL teaching staff for the inclusion of these students in the ordinary classroom, being involved in the tasks that these pupils perform within the ATAL classroom, and co-organizing different actions on intercultural education in the school. School counselors must therefore have a leadership role in this important process [

52,

69].

Therefore, it seems appropriate to reflect on the perceptions and assessments that they make regarding the educational attention received by immigrant pupils and the opportunities that the ATAL and school counseling can generate for the promotion of intercultural education. In this line we agree with the idea that [

70] school guidance counselors have become true points of reference for educational attention to immigrant students.

2. Materials and Methods

This work is based on a qualitative ethnographic study, using in-depth interviews as the information-gathering procedure. When we draw up the ethnography of a certain educational social unit (a family, a school, a class, a faculty, etc.), we are trying to build a theoretical structure that responds to what is going on in the social unit being studied [

71].

2.1. Research Aims

In this work, we propose three general objectives:

To ascertain the perceptions of counselors on the educational attention received by immigrant pupils;

To analyze the educational counselors’ assessments of the ATAL as an intercultural device; and

To determine the functions implemented and the role of the counselor in promoting intercultural education.

2.2. Participants

The sample that took part in this study consisted of a total of four counselors: two of them from Educational Guidance Teams in the provinces of Huelva and Cádiz, and two counselors assigned to the counseling departments of two secondary schools in Huelva province. The sampling type used to select the cases was intentional, as the participants were chosen because they presented different trajectories and professional paths of special interest to achieve a richer and more diverse view regarding the object of study and, in addition, their schools had temporary language adaptation classrooms.

Next, we briefly describe the main characteristics of the counselors. First of all, it should be noted that the four informants were women, although it was not a prerequisite of the research, between 36 and 55 years of age. Their teaching experience ranged from 11 to 33 years, and three of them had gone through other educational stages. They had been working as school counselors for between 1 and 18 years. All had experience in contexts of cultural diversity and had worked with immigrant pupils and in schools with ATALs. Their academic qualifications were in teaching, pedagogy, psychology and psychopedagogy. Only one counselor’s locality and province of birth coincided with her usual place of residence. The rest either came from outside the Andalusian community, or their town and province of birth did not coincide with their usual residence due to where they were assigned after joining the teaching staff.

2.3. Data Gathering Instrument: In-Depth Interviews

The in-depth interview is a qualitative strategy that enables us to ask a series of open questions in order to collect descriptive information and opinions from the informants to whom it is applied. The authors of [

72] (p. 458) add that in-depth interviews reveal “how individuals conceive their world and how they explain or give meaning to important events in their lives.” In-depth interviews are designed under a protocol of questions organized under a previously designed script, although at the same time it remains open to some of the questions that are developed to help increase understanding of the topic being addressed.

This in-depth interview protocol (

Table 1) was divided into two parts: The first part included aspects carried out with the project and features of the interview itself (date, time, duration, place, contextualization, etc.) and the personal data of the interviewee (sex, age, locality and province of birth, habitual place of residence, training, time on the job, and teaching experience). The second part of the interview, object of analysis, revolved around the main dimensions or categories established from the research questions that guided the study, namely:

- (1)

Educational care received by immigrant pupils: main measures applied and critical issues (problems or challenges);

- (2)

Assessment of the ATAL as a key device in the educational response received by immigrant students: functions, importance, and impact on the management of cultural diversity; and

- (3)

Role of the school counselor in the management of cultural diversity and the promotion of interculturality: functions, implemented actions, strengths, and weaknesses.

Setting out from these initial dimensions and depending on the contributions of the counselors, different categories of analysis emerged, which helped to specify the object of study. Among others, these included the family–school relationship as an educational issue or challenge, the learning of Spanish as a condition for the educational inclusion of immigrant pupils, coexistence as the main scope of action of school counselors, and the relationships and collaboration networks that ATAL counselors and teachers establish for the promotion of intercultural education.

2.4. Data Gathering and Analysis Procedure

As mentioned previously, a qualitative study was carried out using the in-depth interview as the information gathering procedure. The four interviews were held in person, previously arranged with the counselors. They took place in the schools and were recorded under informed consent. The interviews were subsequently transcribed and contrasted with the informants.

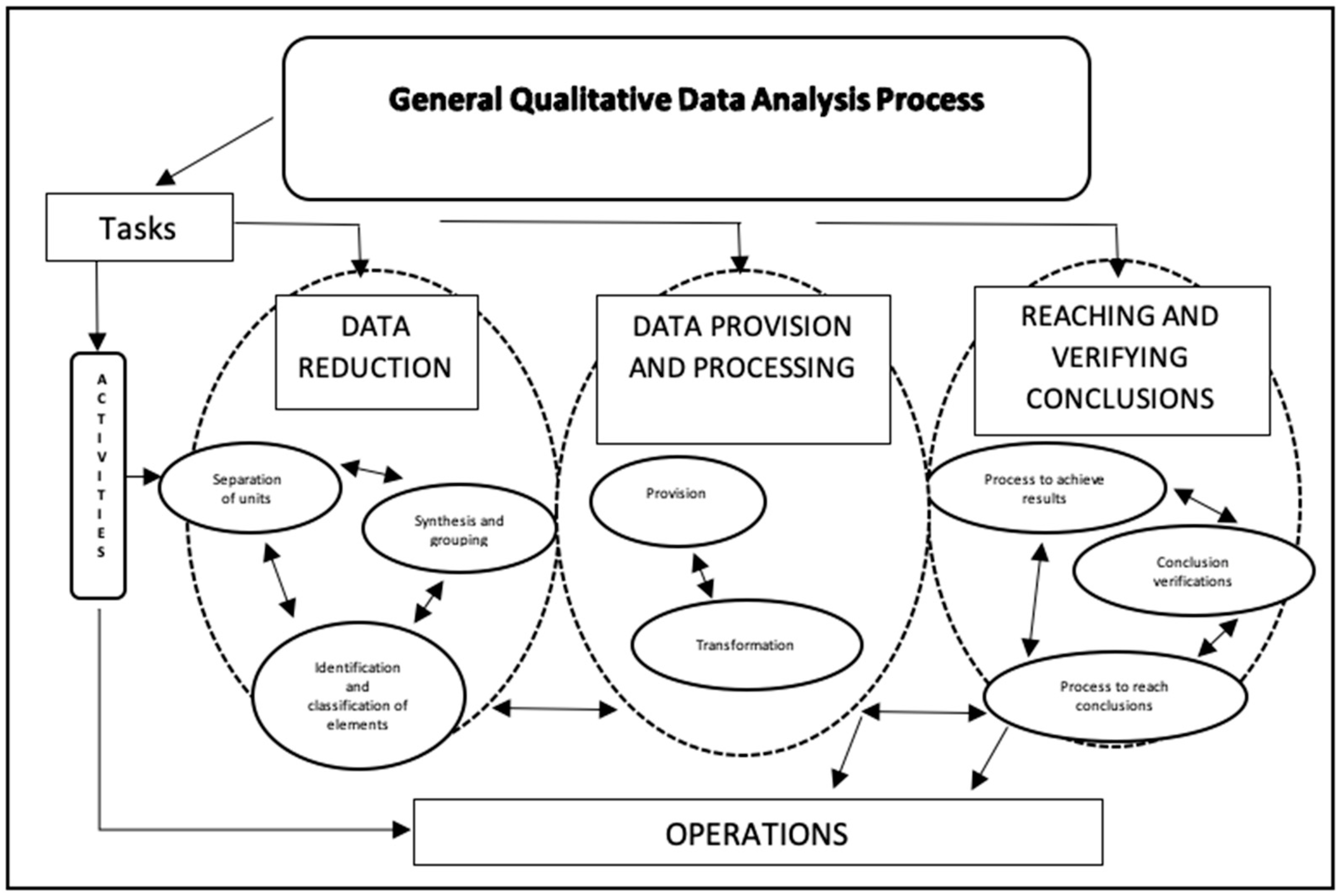

Analysis of the interviews was carried out taking data reduction into account [

73], drawing up a table of categories organized on the basis of the questions asked, establishing categories and organizing the texts of the interviews based on this categorization.

In

Figure 1 [

71] (p. 206), we can observe the general qualitative data-analysis process. It is based on the data-reduction process, where the first step is segregation of the transcribed text into units or elements that will help organize all the information collected in the interviews held.

The qualitative analysis process of the text is carried out, on the one hand, through the deductive construction of categories following one of the methods proposed by [

74,

75], i.e., from a system of pre-set categories. An inductive process is also carried out because other categories emerge from the previous dimensions or categories that guide access to the data. This way, the data manage to reflect the voices and constructions of the participants, with new interpretations of meanings being developed.

Table 1 summarizes the deductive and inductive process followed. In it, we describe the dimensions that respond to the three research questions formulated and the categories that were finally analyzed.

Each transcribed interview was identified according to the order given to the counselors from each school, using the following codes: ENTOR1, ENTOR2, ENTOR3, ENTOR4. In addition, after each code the minute where the informant intervenes was included, alluding to the category being analyzed. Use of the MAXQDA 20 program to categorize, encode, and segment the transcribed interviews facilitated interpretation of the data. The total minutes analyzed after the course of the four interviews was 201, with each interview taking between 39 and 52 min. It should be noted that the total number of entries from the key informants over the course of these interviews was 219.

2.5. Ethical Aspects of the Research

The details of the counselors interviewed were protected, using different names in each of the files corresponding to the interviews held with the four counselors. Before carrying out the interviews, we ensured the informed consent of each of the informants, with no objections being raised.

3. Results

The results are presented based on the three main dimensions or categories for the analysis of qualitative data from the in-depth interviews.

The following sections include the most significant results arising from the analysis of the information of the three dimensions examined that equally respond to the general research objectives.

3.1. Educational Care Received by Immigrant Pupils: Critical Issues (Measures, Problems, or Challenges Pending)

We begin this results section by showing the main most critical issues or pending challenges. One of the challenges in attending to immigrant students in school, according to the team of counselors, focuses on two essential variables: schooling and life (academic trajectory and educational inclusion). On the one hand, these challenges are directed especially towards the attitudinal and not so much towards the academic. One of the informants noted that the main problem that she finds in her school in general, both in Spanish and immigrant students, is “especially in terms of indiscipline, bad behavior in class. The vast majority are children who do not work in class, they are bored, they do nothing, they come without equipment, with their hands in their pockets, that is, they do not bring anything, no backpack or anything, so they are children who get bored in class” (ENTOR1:16′). Another issue they detected is the lack of attention: “That’s the fashion. Life is very fast and then the child also has everything and has very scattered attention. Now almost all the demands that come to me regarding the child are about lack of attention” (ENTOR2:22′). On the other hand, relationships with families were also a challenge, especially with families of pupils of foreign origin: “They already come with the baggage of family issues and you come up against more problems because the family does not help very much. They come here to make money and then leave. Therefore they do not place much importance on education. They are usually working all day; we tell them to come, but it requires an effort from them” (ENTOR2:24′). Finally, another challenge that arose was related to “access to the curriculum on the issue of language because students, even those who come from Latin America, who know the language, also have their difficulties: They have different levels and it is difficult, in principle, even to adapt to our way of speaking because we speak very quickly” (ENTOR3:26′).

In terms of results regarding the schooling process, they show that it is carried out in its natural context and following the school’s guidelines for this task, considering it an open, flexible process that responds to all pupils in the school: “The Head of Studies determines which group the student will be included in, taking into account the ratio of each class. They will be assigned to the group with the fewest students, to compensate [the numbers] a little” (ENTOR1:10′). The high ratio is thus considered a negative aspect and therefore schools should try to organize groups in a heterogeneous way, taking into account their diversity and not trying to create “ghettos” of immigrant pupils by class.

Despite the fact that the schools and the professionals who work in them do everything possible to ensure true inclusion, on some occasions it does not come to fruition due to the characteristics of the pupils: “There is still a long way to go there. I mean, we try to treat them the same, but many times it is also down to them; they can be very peculiar and they can also show a tendency to form closed groups. Many come with prejudices that are very hard for us to get rid of” (ENTOR2:08′).

In general, the counselors’ assessments of the life of the school were positive and they considered that there are usually no problems of coexistence in schools with immigrant pupils: “Of course, I can only comment from the standpoint of the educational teams on the issue of coexistence that these pupils, in general, do not cause any more problems than others. The teachers do not see immigrant pupils as a problem, even though the added effort required to help them may be, but nevertheless, there is no rejection of immigrants” (ENTOR3:35′). In some cases, there may be times when the tutors do not manage to provide personalized attention to this type of student body and it is the ATAL teacher who is responsible for knowing what is happening to them and responding to their needs: “Some children have difficulties in first and second year, and the tutor is not able to attend to them properly, so it would be convenient for the ATALs to look after them. The situation is different depending on the type of school and pupils” (ENTOR4:23′).

Another critical aspect that has to be improved involves the training of teachers in attention to diversity. The counselors outlined that such training is in place, but that it is not provided in a varied format where didactic and organizational strategies are analyzed in terms of attention to diversity or educational inclusion: “There has been something, there have been CEP (Teacher Training Centre) activities... Training is difficult, because requesting a CEP course was not possible, as they are spread throughout the province and more so with this very dispersed province. So, we have some sessions that are held throughout Andalusia, once a year, although last year they were not held, and two days that we do here every year, in which we start by describing what each one does in their class, what materials you use… This way, a very interesting exchange of experiences takes place” (ENTOR4:17′). “I think they should have training to address diversity in general, not specifically. I believe that when the student works, and does not display bad behavior, the teachers try to help” (ENTOR3:12′).

Another of the categories that was analyzed was the relationship with the families of foreign pupils. Our informants emphasized that the families are not 100% involved, but that this happens with all the pupils’ families: “With the family there is a lack of involvement, but that is the case in general, not only with the immigrants. Immigrant families attend and participate at much the same level as other families” (ENTOR1:21′). On the other hand, relationships with families are established like links in a chain, in other words, “management team, families, and pupils last, that is, the tutors and last, the pupil. I do not like to work just with the pupil, because I do not believe that they are the only ones with problems. I believe more in systemic counseling” (ENTOR2:16′). Along this line, it also became apparent that the main problem with families is the language: “It is quite clear that most of the families from Morocco are already settled, they live here and have their lives here, as do many of them from the Eastern European countries too. Some of the children were even born here, so I see another problem of another kind, because the problem of immigration for us is the language, not the student who has been here for 10, 8, or 7 years” (ENTOR3:07′).

Another one of the analysis categories focused on determining the most notable actions on cultural diversity registered by the counselors that help us understand the specific attention to immigrant pupils and that do not pose any pending challenge. In other words, the programs and initiatives that contribute to the reception and inclusion of these pupils in school life. In addition to learning about institutional programs, schools organize other intercultural projects in response to the work carried out with the group of foreign pupils from their schools. In general, the counselors showed some of the activities that take place in their schools: talks, multicultural meetings, cultural gatherings, theatre events: “Normally, many interculturality activities are carried out” (ENTOR2:15′). “Activities are prepared: For example, an Arabic alphabet workshop was held with the children in the class and they got the Arab children involved. It is more about making their culture known to the natives than the other way around, because you could say they are already integrated” (ENTOR1:09′). In addition, organized activities are held under the tutorial action plan, so they are not unscheduled activities: “Then we do some tutoring activities to raise awareness of the issue of interculturality and we show films on racism, xenophobia, that deal with the issue of interculturality and some groups receive tutoring on these issues” (ENTOR3:20′).

Along the same lines, the actions, programs, and initiatives that the key informants were particularly aware of were those derived from the social services of the local authorities corresponding to the municipalities: “With the Coexistence and Social Cohesion Foundation we work very well, also with the city council and with social services, although in terms of actions, let’s say of a more cultural nature, there is no communication” (ENTOR1:25′). “There are other programs such as: ‘Children like me around the world…’ and it is very good, very didactic. It is good to have in classroom libraries” (ENTOR2:28′). Other experiences were also considered: “The regional government issued some boxes that each school had at its disposal to work on in the classrooms. Then there was a program from the Cervantes Institute, on teaching Spanish for foreigners (which is no longer free). The Head of Studies had to register the pupil and check that they were passing the exams that were done online” (ENTOR4:33′). Finally, the Linguistic Support for Immigrants program by the Junta de Andalucía was focused on students learning the language of the host country and thus contributing to their social integration: “They also have accompaniment and minor adaptations in some vocabulary areas” (ENTOR3:40′).

3.2. Assessment of the ATAL as a Key Device in the Educational Response Received by Immigrant Students

In this second dimension of analysis, we present the main results of the assessments of the ATAL as an intercultural device that is made available to immigrant students in schools.

Regarding the functioning of ATALs, although all the classrooms have the same objective, each of them is organized according to the availability of the schools in terms of spaces, schedules, etc. and under joint coordination between the counselor and ATAL teachers: “Regarding how the ATALs operate in schools, location has always been a problem. They have not usually had a classroom for their exclusive use and have had to adapt to the possibilities of each school. At first, we came across teachers and we did not know who they were or what they were doing there. And the relations with the tutors were usually discreet, as the support within the classroom could not be carried out due to lack of time” (ENTOR4:45′). In this sense, some schools had information on the students who came from early childhood education and primary and who would access the secondary stage: “At the outset we see the list of students who are likely to need support for these levels and we have information from the school, specifically the transit program. We draw up a list, an assessment, and an organization of schedules” (ENTOR3:47′).

In addition, one of the informants placed special emphasis on the importance of the ATAL classroom as a space where intercultural relations are promoted: “We are very lucky to have the ATAL classroom, because each student contributes their culture, their points of view, their knowledge, their ways of proceeding… This is very positive because it enriches the teaching–learning processes, helps us understand their cultures, helps us to open our minds, and, above all, to work on the main values: respect, tolerance, and empathy” (ENTOR2:42).

On the other hand, the counselors’ personal evaluations of the ATAL teaching staff were very positive, considering them a key part in the teaching–learning processes of foreign students in schools: “Very positive. She is a woman who has been around for many years, she knows the children and the families. She also teaches support classes in the afternoon; she is a person who is a heavyweight in this school, they ask her opinion on everything” (ENTOR2:35′). “The assessment is highly positive. As for the schools, families, and the rest of the teaching staff, the role of the ATALs has been fundamental to achieving the incorporation of students of foreign origin into the educational system” (ENTOR4:48′).

Although ATAL teachers do not actively participate in faculty and department meetings, there is a very good relationship with the teachers who work with them, informing them of the academic and attitudinal aspects of the children who attend the ATAL: “All this is assumed by M., so the rest of the school staff simply participate, but she is the one who organizes it” (ENTOR1:34′). The involvement of ATAL teachers is very important for this device to respond to the needs of immigrant pupils both outside and within the ATAL classroom: “She is unaware of the measures we take at the department level in general. I tell her about it afterwards” (ENTOR1:36′).

Finally, the most important assessment of ATAL teachers described the importance of the relationships they establish with the students, not only academically but also on a personal level, as they offer confidentiality, understanding, support, and trust: “Well, for me, the main thing is the relationship that the teacher has with the pupils. She is a person who really motivates them and afterwards the students feel very safe. I really like how she organizes the work with the different ages, the type of work she proposes through the teaching units. The student feels very comfortable and well looked after in that classroom, because in the ordinary classrooms there are many students” (ENTOR3:47′).

3.3. Role of the School Counselor in Management of Cultural Diversity and Promotion of Interculturality

Finally, in this third dimension, we analyze the important role played by the school counselor as a manager of cultural diversity and promoter of intercultural education.

The group of counselors intervenes from various standpoints, for example, by proposing activities in a coordinated manner with other professionals from the school: “We coordinate, I propose, there are ETCP (Educational and Psychopedagogical Guidance Team) meetings at which I am present, I propose, they propose…” (ENTOR2:09′). In addition, they act in response to the demands from families, so another one of their functions consists of offering guidance to families: “Yes, I intervene. We usually get a lot of parents coming and the tutors delegate the cases to me when they have difficulties with a parent and do not know how to act. Years ago, we used to hold meetings to explain things better; we have translated documents, but they are becoming less and less necessary. There are times that if we do a specific awareness-raising activity, maybe I go with a tutor, because I do not feel prepared and I will do that tutoring session with them, but it is not usually necessary.” (ENTOR3:16′).

On the other hand, although we highlighted in the category of schooling process in general that all pupils follow the same schooling procedure whether they are foreigners or not, it is necessary to specify some nuances regarding this process of immigrant students. In this sense, “the Head of Studies determines which group they will be placed in, and depending on the number of students, we try to insert them…” (ENTOR1:05′). The counselors play an important role in this schooling process because although this work is carried out by the Head of Studies, this professional will contribute their premises so that the students can adapt to the school, the classroom, their peers, the system: “Normally, the study department together with the guidance department are in charge of studying where to place each immigrant student so that, first, they can help them with the language.” In addition, the Head of Studies and the counselor are responsible for “informing the educational team and the ATAL teacher about the new immigrant pupils, as well as their characteristics and all the information they have available” (ENTOR3:10′). “We are adapting it, for example, in reception so that they feel comfortable because on many occasions they are apprehensive when they come. Then we talk with the children, we see what level they have, we see what class we are placing them in…we monitor them” (ENTOR2:11′). It is also possible to proceed in other ways when it comes to educating immigrant pupils, such as resorting to telephone calls to find out about the schooling possibilities for students arriving in that locality: “The ECE and primary schools notify us that they have immigrant pupils and ask whether they can come to school in our secondary.” (ENTOR4:08′).

Another function of the counselors brought to light in the results consists of advising and guiding families about their children’s teaching–learning process and being receptive to this type of support or guidance: “Many times, the problem is not with the children, but rather in the family. They are given a lot of guidance and advice on where to go.” We give a lot of guidance to families on how to work at home with their children” (ENTOR2:39′). Sometimes this task is complicated due to the low participation and involvement of families in the schools for various reasons, as was also commented in the first dimension of analysis regarding the relationship with the families of foreign pupils: “With the family, there is a lack of involvement. Most of these parents are farmworkers and it is difficult for them to come, not because they do not want to, but because they cannot. However, when they are called for tutoring, they usually come” (ENTOR1:40′).

Coordination work is essential so that students feel integrated in the school and especially in their classroom. ATALs must therefore coordinate with the teaching staff: “She also does a lot of work with people from the language department and with other departments. She attends the evaluation sessions for the children who have levels where they do not yet know the language and participates in the decisions that are made jointly about the type of reinforcement that should be given to each pupil” (ENTOR1:13′).

In addition, they coordinate with the management team, with whom they have numerous meetings: “I meet with the principal first, because I tell the management team all the actions I take. Then, with the ATAL teacher—we are very coordinated and she always asks me for an opinion on didactic planning and assessment. We do coordinate with each other quite closely, otherwise it is impossible to do any follow-up” (ENTOR2:30′). They also coordinate, of course, with the group tutors: “The tutors are the key part; you will see that I work alongside the tutor. It is they who talk to the family, but always through the tutor. I never skip that figure, as the tutor is the one who knows the children and their families the most.” (ENTOR2:32′).

The counselors state that the roles they play are diverse. Among others, there is that of advising, guiding, coordinating, monitoring, and diagnosing the entire educational community: families, tutors, teachers, management teams, and students: “A little of everything, especially advising the family, teachers, and students. The thing is, in order to talk to the pupils first I have to talk to the families, and before that with their tutors. Especially with immigrants, if they come from another school, we will have a look at what they bring; if they have curricular adaptations, more or less the level of language they bring, if they have to be placed in a lower course… usually they ask me for my opinion on everything. We work in a highly coordinated manner, which is important. Other functions also include detecting the needs the children may have, diagnosis and monitoring… Giving a lot of advice to tutors and parents, but it is really hard work. Some pupils do need adaptations, but the majority do not, and simply need to get up to date with the language so they can keep up with the pace of the class” (ENTOR2:40′).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Intercultural education is conceived as an educational approach that must respond to the needs of students and attend to the diversity of schools in the pursuit of total educational inclusion. To this end, it is essential to set out from respect for cultural diversity and promote positive spaces for coexistence. If we start with this idea, we are responding to the main goal of education, which is responsible for ensuring education for all [

1]. Certainly, to achieve this end, it is the task of all members of society to become aware of the importance of intercultural education to ensure quality education. Sometimes it is necessary to generate changes and this “would encourage a better integration of cultural diversity in the life of schools, instead of treating it as something negative/deficient, as an occasional, individual problem isolated from the sum of activities for schoolchildren and other members of the educational community” [

76] (p. 615).

In recent years, the arrival of immigrant pupils in schools has been a major challenge for schools in general, and for counseling professionals in particular, since they must attend to, assist, and give advice to the students they encounter in their process of cultural adjustment and family reorganization [

60].

The educational administrations have also helped by increasing the resources destined for attention to diversity, both for students in schooling issues and towards positions closer to social justice. On one hand, as the main resource or device we find the special Spanish learning classroom for newly incorporated immigrant students, called ATAL in Andalusia [

13,

14]. And, on the other hand, access to school for new professionals (intercultural mediators, social educators, Spanish teacher) and their collaboration with school counselors has also made it possible to improve these cultural diversity management processes, advocating for inclusive leadership, a collaborative leadership where tasks are distributed and in which all the agents involved are leaders in favor of the principles of inclusion [

69].

Next, we would like to present the main conclusions drawn from the analysis of the interviews, connecting them to the three dimensions set in this study:

- (1)

The educational care received by immigrant pupils: main measures applied and critical issues (problems or challenges);

- (2)

An assessment of the ATAL as a key device in the educational response received by immigrant students: functions, importance, and impact on the management of cultural diversity; and

- (3)

The role of the school counselor in the management of cultural diversity and the promotion of interculturality: functions, implemented actions, strengths, and weaknesses.

Regarding the first dimension, we would like to highlight that the indiscipline and lack of attention on the part of the pupils, the limited involvement and participation of families, and the limited access to the curriculum by these students due to the language issue [

77] have also posed challenges to educational counselors’ remit. To this end, they insist on the imminent collaboration of the teaching staff and on activating processes to motivate the students and define strategies to combat these issues. In this sense, teachers present some training needs related to educational attention to diversity in cultural contexts, although we appreciate that the training that is offered is not very broad, despite the insistence on the need for all professionals to be trained in intercultural education and even more so, practicing teachers and future teachers who are being trained in universities [

8,

10]. In addition, counselors must also seek new opportunities for ongoing and up-to-date training on multicultural counseling to become multiculturally competent [

58].

Regarding coexistence in school, there are usually no major problems. In some cases, there may be times when tutors do not achieve personalized attention to this type of student body and it is the ATAL teaching staff who are charged with knowing what is happening to them and responding to their needs. Likewise, the school counselor, in addition to advising the pupils at an academic and professional level, must also encourage coexistence in the school, promote intercultural relations, and accompany the students in their personal development processes [

59].

In relation to the participation of the families of immigrant pupils in their children’s education, we can say that it is very scarce, almost nil. Many of the arguments are grounded in hypotheses and beliefs that are usually based on stereotypes and prejudices towards other cultures [

59,

78,

79]. Despite these drawbacks in the participation of the families of immigrant pupils, the school counselor offers them help and advice in everything related to their children’s education, both at the outset and throughout the school year.

As for considerations and evaluations made from the point of view of educational counseling, it is noted that these services for immigrant pupils are essential, on the one hand, in supporting the acquisition of linguistic and communicative skills and, on the other, in allowing the integration of these pupils in the school and social environment in the shortest possible time and with assurances of progress in the ordinary classroom [

15]. In this sense, all the classrooms have the same objective. Each of them is organized according to the availability of the schools in terms of spaces, schedules, etc. and under the coordination between the counselor and the ATAL teacher.

As a conclusion in this dimension, we would like to pinpoint that school guidance counselors have become true points of reference for educational attention to immigrant students.

The second dimension refers to the assessment of the ATAL as a key device in the educational response received by immigrant students: functions, importance, and impact on the management of cultural diversity. It is worth highlighting in this study the very positive assessments expressed by the counselors on a personal level about ATALs, assigning ATAL teachers an essential task in the educational care of immigrant students. They know the pupils and their families, they have specific training to care for these students and their integration into the classroom, they are points of reference in their schools, and they always participate in the most important school decisions. The main assessment shows that the ATAL teaching staff is important in the lives of immigrant pupils, becoming so more personally than academically.

The coordination role in general but specifically among these professionals becomes relevant: counselors, ATAL teachers, special education teachers, and tutors. For this reason, the counselors valued very positively the degrees of collaboration with the rest of the educational agents [

45] so that this work forms part of the school culture.

One of the counselor’s tasks is to advise immigrant pupils as a facilitator of cultural knowledge and as the manager of multicultural processes [

52,

56,

57] both on arrival and throughout the academic year. In line with [

80], we insist on the idea that it is necessary to give another or a different approach to the task of the counselors towards the personal work that they carry out with each student as well as promoting further studies and research that take into account the type of cultural orientation and accompaniment provided to them.

Finally, in the third dimension, the main results are presented in relation to the role of the school counselor in the management of cultural diversity and the promotion of interculturality: functions, implemented actions, strengths, and weaknesses.

We agree with [

52] in that counselors have different roles in their work with immigrant pupils: They are charged with promoting assimilation of the dominant culture, self-facilitators in a process of inclusion more individual than collective, immigration and school affairs specialists, and cultural “translators” who see this process as an exchange rather than merely adaptive.

Another role of counselors is related to the development of specific projects and programs to address diversity. On the one hand, professional counselors know the actions, programs, and initiatives that emanate from the educational administrations, but our research reveals that the design and development of cultural projects is especially valued, with the work and organization of ATAL teachers being the main promoters in the organization and management of cultural diversity programs and experiences. In this sense, counselors are not primarily responsible for promoting knowledge of culture and managing multicultural processes [

52,

56,

57]. The design and development of training programs that especially work on emotional competences and favor an inclusive climate takes on a special urgency [

60].

After the launch of our study and the results obtained, the measures and actions that counselors have to carry out to care for immigrant students were confirmed, according to the Order of January 15, 2007 of the Junta de Andalucía. We conclude by summarizing these actions carried out by counselors:

- −

Design and development of intercultural education measures;

- −

Participation in the initial meetings with the tutor to determine the degree of linguistic competence of the immigrant pupils in school;

- −

Advising both the Head of Studies and the ATAL teaching staff to coordinate the tasks of detection, reception, and psychopedagogical and curricular assessment;

- −

Guiding teachers on the relevance of each pupil’s program attendance, as well as establishing the appropriate curricular adaptations;

- −

Participating in the decision-making on the continuity or not of immigrant pupils in the ATAL support groups;

- −

Coordinating with the ATAL teachers in each province; and

- −

Knowing the classroom programming designed by the ATAL faculty, where individualized actions with each student in the program are recorded.

This study highlights the importance of the school having the possibility and assuming the responsibility of transforming itself into a scenario where it is committed to promoting interculturality. To do so, it must count on the imminent collaboration of all educational agents and the community. In this sense, the counselor is an important cog in the machinery of cultural diversity management in schools. To this end, the possible changes in teaching–learning methodologies or in curriculum flexibility also acquire special relevance because, on occasion, teachers are strictly focused on teaching their disciplines, leaving aside the acquisition of tools and strategies for educational attention to diversity. These teachers delegate the attention to immigrant pupils to the Spanish teachers and counselors [

45,

81].

Coinciding with [

66,

67,

68], the key to getting schools to commit to educational inclusion lies not only in the role played by the counselor as manager and promoter of cultural diversity, or other specialists, but also in the inclusive leadership that the school institution is capable of implementing. To this end, the involvement of all members of the educational community is essential, with school counselors (due to the skills and functions they deploy and perform in the management of cultural diversity) as key figures in the achievement of a school for all.

Among the limitations of the study, we would like to note the small size of the sample. It was applied to a reduced number of counselors, so it would be convenient to expand the sample for future studies on this topic. It would also be interesting to interview them a greater number of times. In this way, we could both define other recurring themes in terms of cultural diversity, and comment on useful strategies they implement.

The results are an approximation to the study of the role of counselors on cultural diversity. For future lines of action, it would be necessary to continue deepening the subject using different approaches and methodological designs that provide us with a broader and deeper vision of the phenomenon, such as case studies that include other data collection strategies such as discussion groups.