Mycological Indicators in Evaluating Conservation Status: The Case of Quercus spp. Dehesas in the Middle-West of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

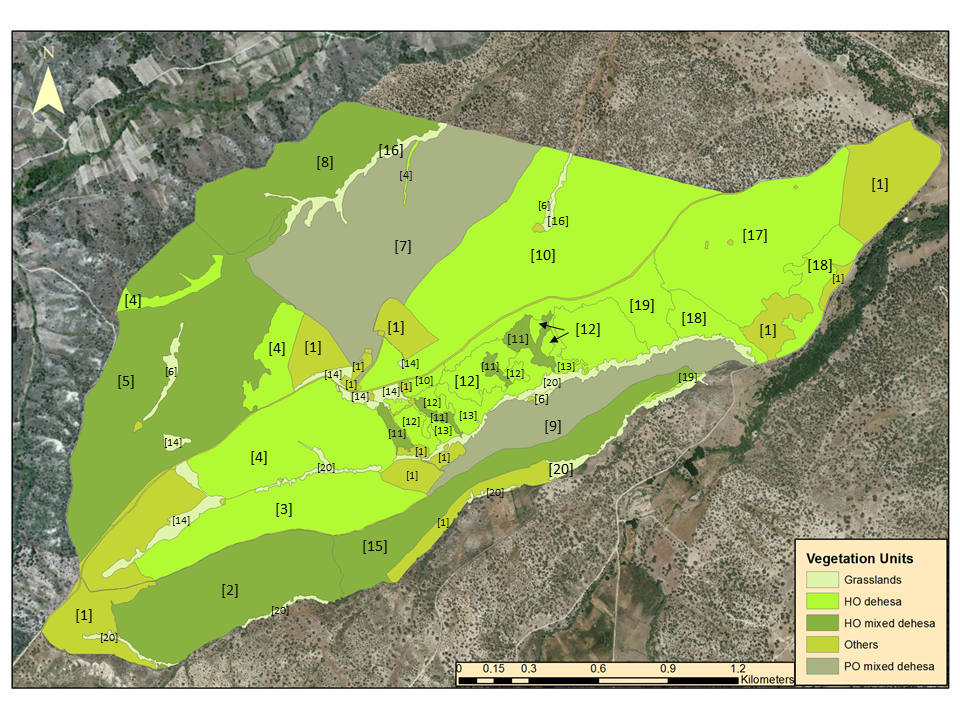

2.2. Delimitation of Vegetation Units

2.3. Mycological Surveys

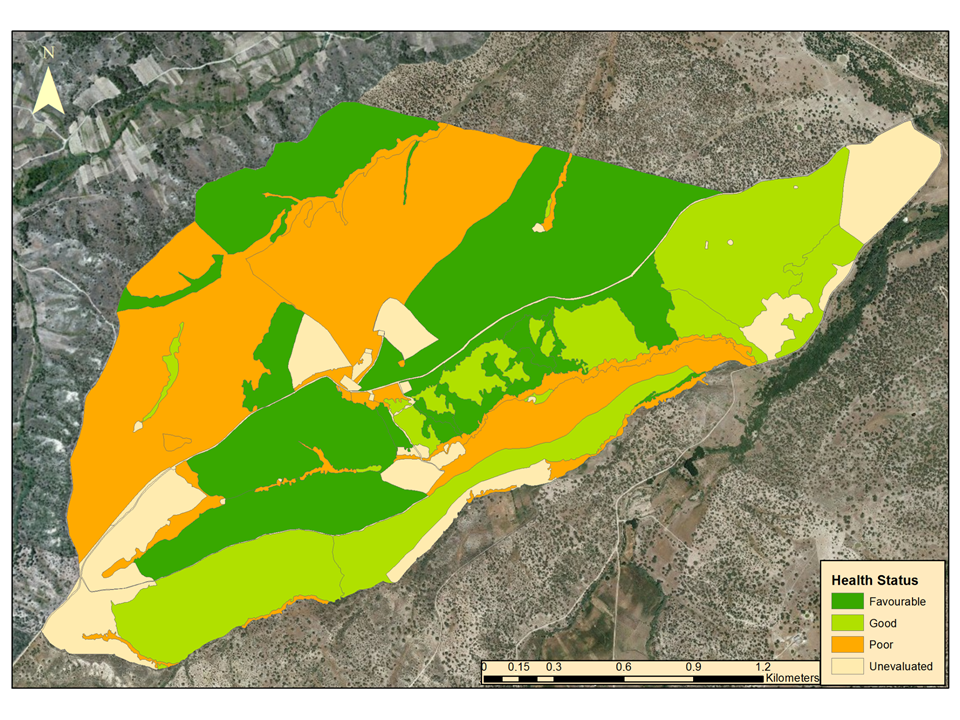

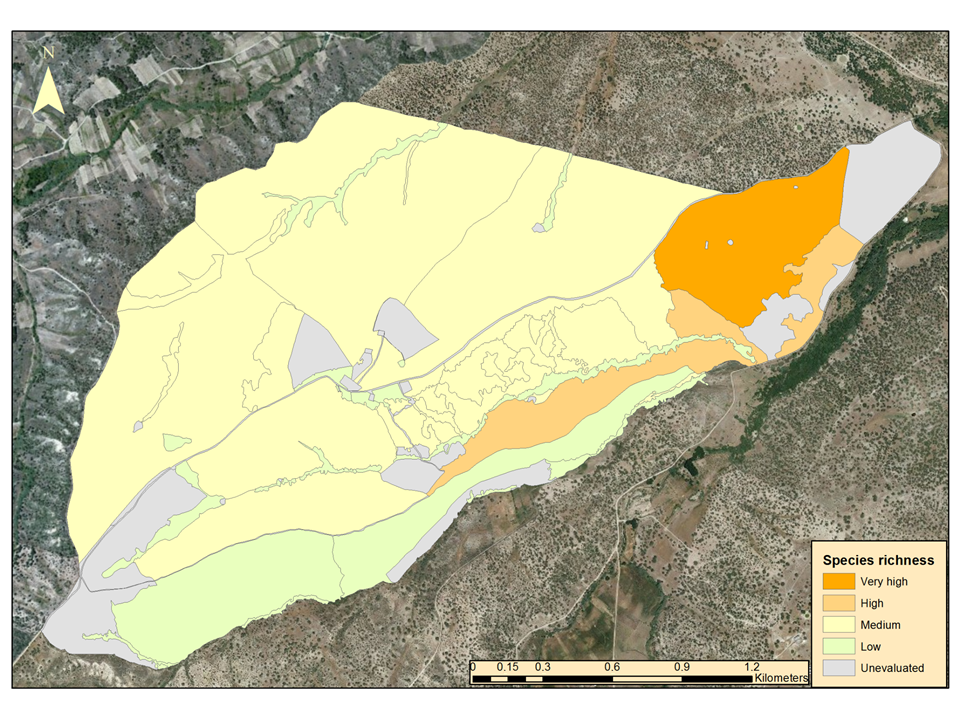

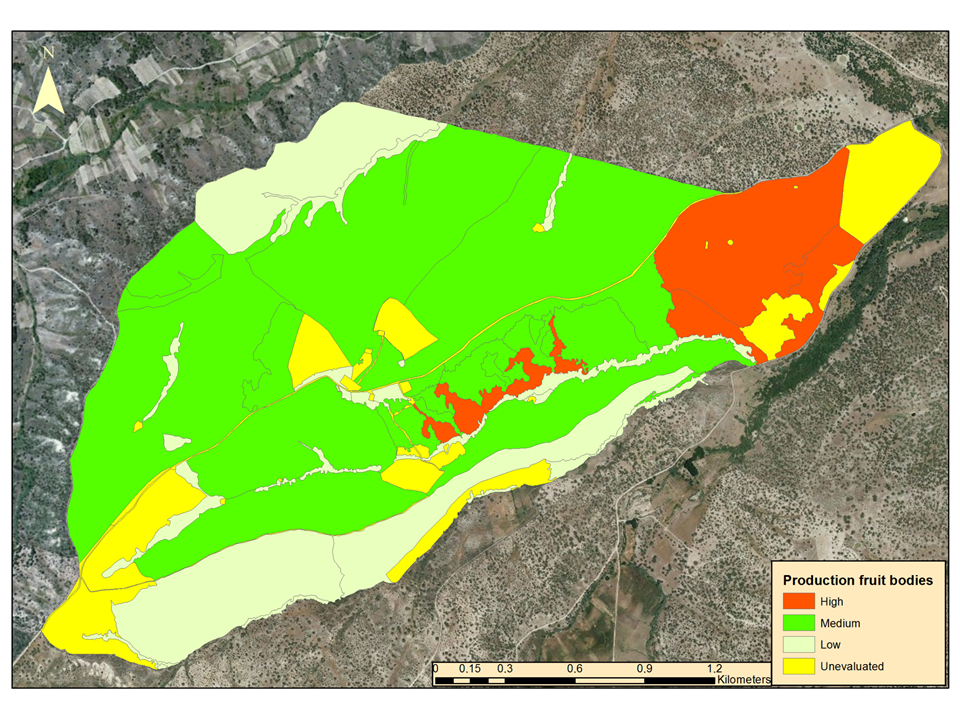

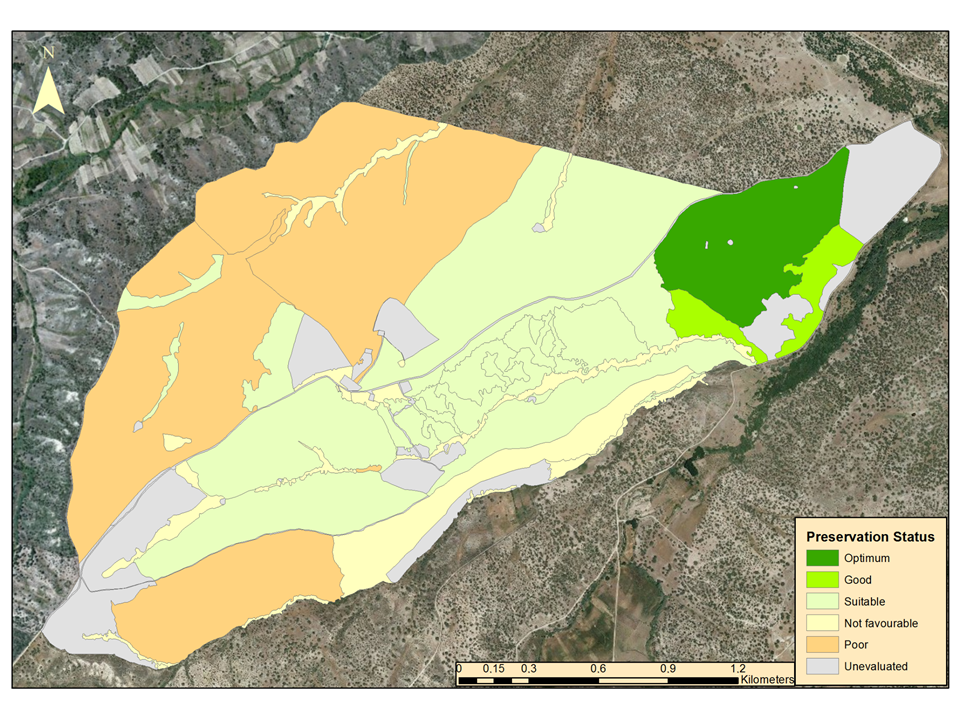

2.4. Assessment of the Conservation Status

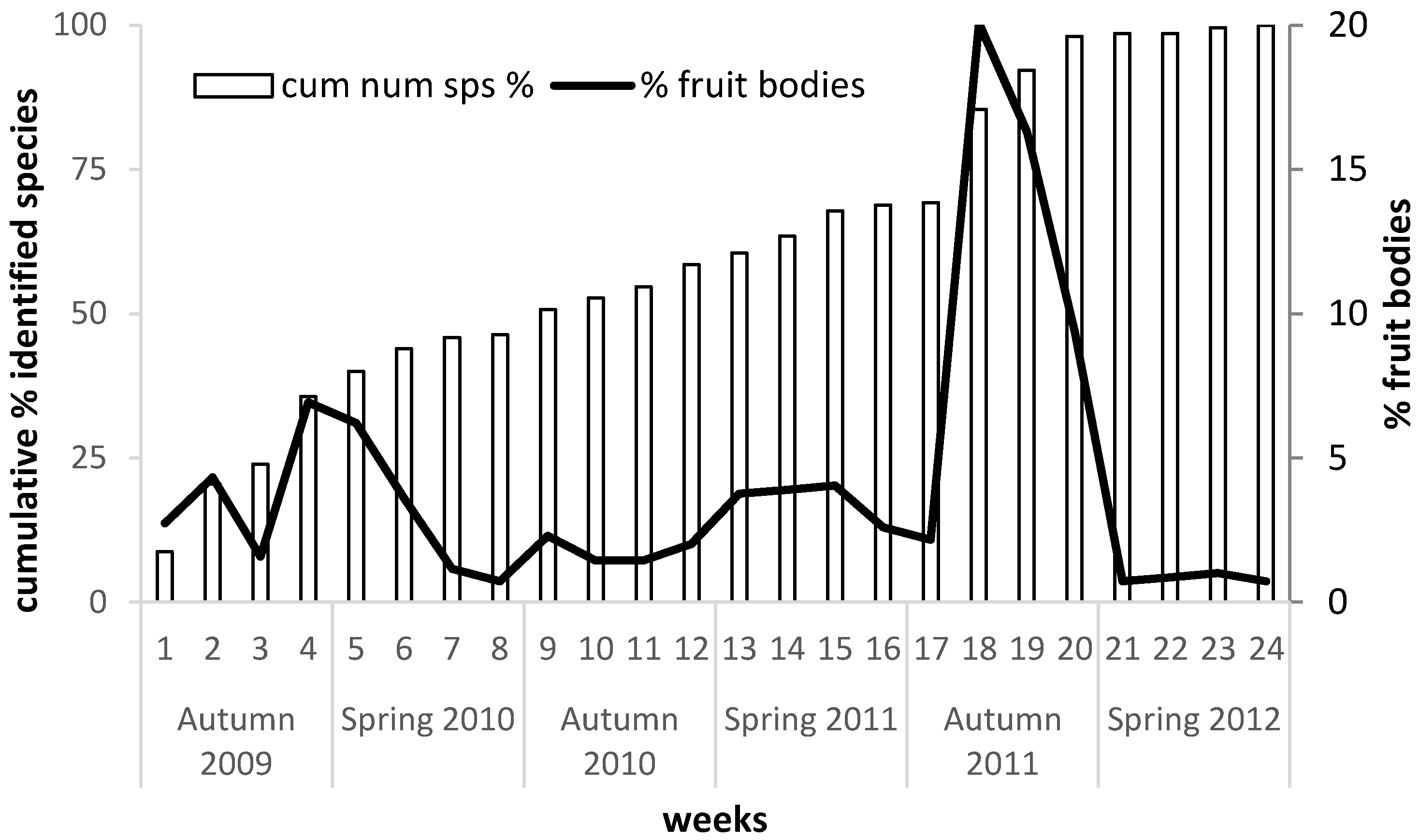

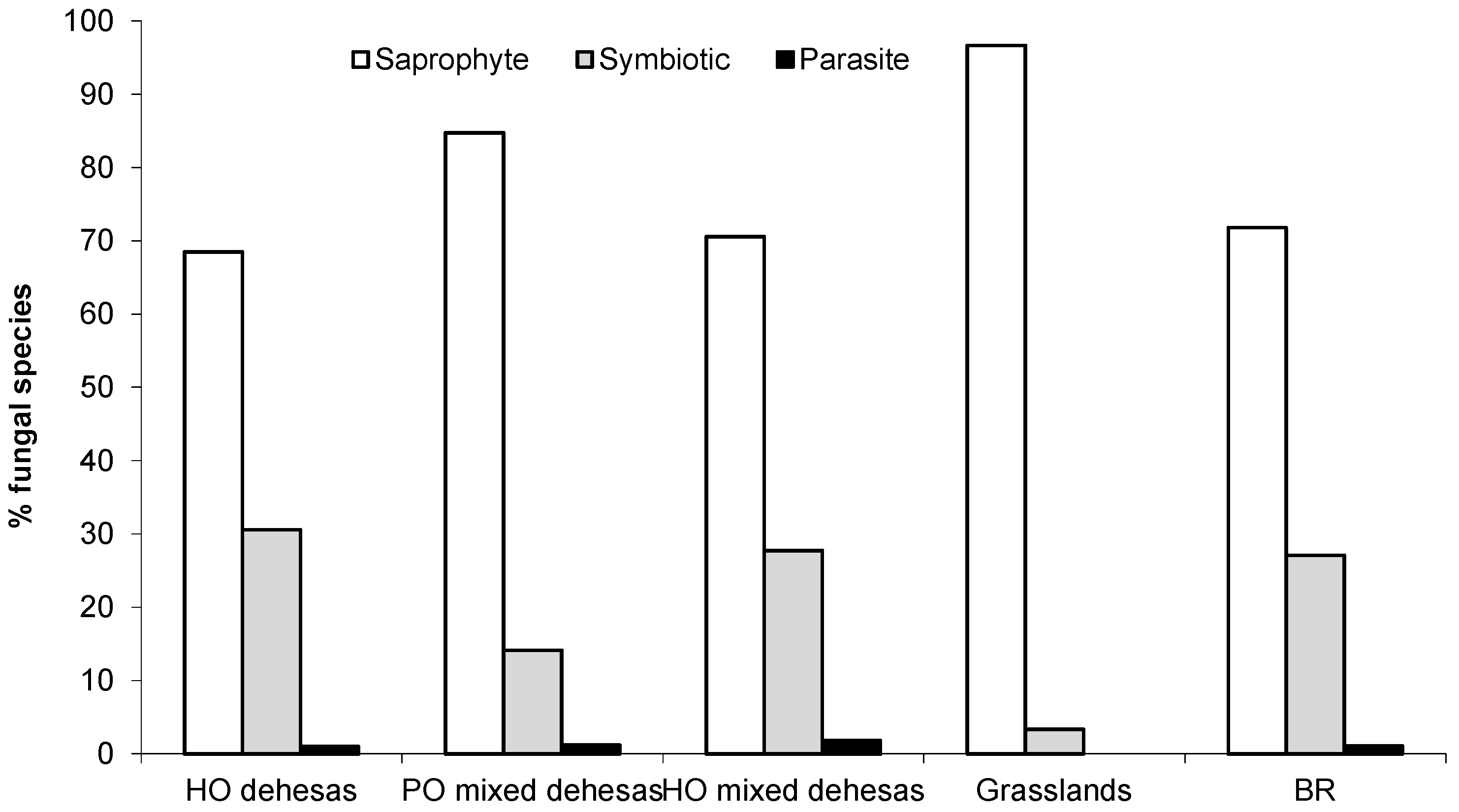

3. Results and Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gratton, L.; Hone, F. Les défis de la forêt privée: La conservation, l’utilisation durable de la forêt et l’écotourisme. Téoros 2006, 25, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Goldmann, K.; Schöning, I.; Buscot, F.; Wubet, Y. Forest Management Type Influences Diversity and Community Composition of Soil Fungi across Temperate Forest Ecosystems. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- du Bus de Warnaffe, G.; Devillez, F. Quantifier la valeur écologique des milieux pour intégrer la conservation de la nature dans l’aménagement des forêts: Une démarche multicritères. Ann. Sci. 2002, 59, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sacchis Lopes, M.; Kozhikkodan Veettil, B.; Saldanha, D.L. Assessment of Small-Scale Ecosystem Conservation in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest: A Study from Rio Canoas State Park, Southern Brazil. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baldrian, P. Forest microbiome: Diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perotto, S.; Angelini, P.; Bianciotto, V.; Bonfante, P.; Girlanda, M.; Kull, T. Interaction of fungi with other organisms. Plant. Biosyst. 2013, 147, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lonsdale, D.; Pautasso, M.; Holdenrieder, O. Wood-decaying fungi in the forest: Conservation needs and management options. Eur. J. For. Res. 2008, 127, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Pavlov, I.N.; Kim, M.-J.; Park, M.S.; Oh, S.-Y.; Park, K.H.; Fong, J.J.; Lim, Y.W. Investigating Wood Decaying Fungi Diversity in Central Siberia, Russia Using ITS Sequence Analysis and Interaction with Host Trees. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chávez, D.; Pereira, G.; Machuca, Á. Estimulación del crecimiento en plántulas de Pinus radiata utilizando hongos ectomicorrícicos y saprobios como biofertilizantes. Bosque 2014, 35, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, A.F.S.; Alexander, I. The ectomycorrhizal symbiosis: Life in the real world. Mycologist 2005, 19, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniati, E.; Arfarita, N.; Imai, T.; Higuchi, T.; Kanno, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Sekine, M. Potential bioremediation of mercury-contaminated substrate using filamentous fungi isolated from forest soil. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ibarra, E.; Gómez-Martín, M.B.; Armesto-López, X.A. Climatic and Socioeconomic Aspects of Mushrooms: The Case of Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnolds, E.; de Vries, B. Conservation of fungi in Europe. In Fungi of Europe—Ivestigation Recording and Mapping, 1st ed.; Pegler, D.N., Boddy, L., Ing, O., Kirk, P.M., Eds.; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 1993; pp. 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, F.; Moreau, P.A.; Selosse, M.A.; Gardes, M. Diversity and fruiting patterns of ectomycorrhizal and saprobic fungi in an old-growth Mediterranean forest dominated by Quercus ilex L. Can. J. Bot. 2004, 82, 1711–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abrego, N.; Bässler, C.; Christensen, M.; Heilmann-Clausen, J. Implications of reserve size and forest connectivity for the conservation of wood-inhabiting fungi in Europe. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 191, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, G.; Pulido, F.J. The Functioning, Management and Persistence of Dehesas. In Agroforestry in Europe: Current Status and Future Prospects, 1st ed.; Rigueiro-Rodríguez, A., McAdam, J., Mosquera-Losada, M.R., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media, B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 127–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Martínez, C.; Benito-Peñil, D.; García de Enterría, S.; Barajas-Castro, I.; Martín-Herrero, N.; Pérez-Ruiz, C.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Sánchez-Agudo, J.A.; Rodríguez-de la Cruz, D.; Galante-Patiño, E. Manual de Gestión Sostenible de Bosques Abiertos Mediterráneos; Castilla Tradicional: Valladolid, Spain, 2012; pp. 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Calcerrada, R.; Novillo, C.J.; Millington, J.D.A.; Gómez-Jiménez, I. GIS analysis of spatial patterns of human-caused wildfire ignition risk in the SW of Madrid (Central Spain). Landsc. Ecol. 2008, 23, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Off. J. Eur. Union 1992, L 206, 7–50. [Google Scholar]

- VV.AA. Bases Ecológicas Preliminares Para la Conservación de los Tipos de Hábitat de Interés Comunitario en España; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural y Marino: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.F.S. Fungal diversity in ectomycorrhizal communities: Sampling effort and species detection. Plant. Soil. 2002, 244, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, P.; Poumarat, S. Amaniteae. Fungi Europaei; Candusso: Origgio, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- García Jiménez, P.; Pérez Gorjón, S.; Sánchez Rodríguez, J.A.; Sánchez Sánchez, J.; Valle Gutiérrez, C.J. Setas de Salamanca; Diputación de Salamanca, Naturaleza y Medio Ambiente: Salamanca, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, J. Boletus s.l. Fungi Europaei; Candusso: Origgio, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, L.A. Agaricus s.l. Fungi Europaei. Volume 1; Candusso: Origgio, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, L.A. Agaricus s.l. Fungi Europaei. Volume 2; Candusso: Origgio, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CABI Index Fungorum. Available online: http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/names.asp (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Baptista, P.; Martins, A.; Tavares, R.M.; Lino-Neto, T. Diversity and fruiting pattern of macrofungi associated with chestnut (Castanea sativa) in the Trás-os-Montes region (Northeast Portugal). Fungal Ecol. 2010, 3, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreno, G. Setas Micorrrizógenas, Parásitas y Saprófitas; Una Forma de Valorar el Impacto Ambiental en Nuestros Bosques; Congress Communication: Laredo, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Saitta, A.; Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Brocca, L.; Tedersoo, L. Tree species identity and diversity drive fungal richness and community composition along an elevational gradient in a Mediterranean ecosystem. Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, F.; Millot, S.; Gardes, M.; Selosse, M.A. Diversity and specificity of ectomycorrhizal fungi retrieved from an old-growth Mediterranean forest dominated by Quercus ilex. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtomäki, J.; Tomppo, E.; Kuokkanen, P.; Hanski, I.; Moilanen, A. Applying spatial conservation prioritization software and high-resolution GIS data to a national-scale study in forest conservation. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 2439–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Lambraño, R.E.; Rodríguez de la Cruz, D.; Sánchez-Agudo, J.A. Spatial oak decline models to inform conservation planning in the Central-Western Iberian Peninsula. Ecol. Manag 2019, 441, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, A.; Croneborg, H. 33 Threatened Fungi in Europe; Complementary and Revised Information on Candidates for Listing in Appendix I of the Bern Convention: Uppsala, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, A.; Mueller, G.M. Applying IUCN red-listing criteria for assessing and reporting on the conservation status of fungal species. Fungal Ecol. 2011, 4, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calonge, D. Apuntes para la futura Lista Roja de hongos españoles. Bol. Soc. Micol. Madr. 2004, 28, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann-Clausen, J.; Barron, E.S.; Boddy, L.; Dahlberg, A.; Griffith, G.W.; Nordén, J.; Ovaskainen, O.; Perini, C.; Senn-Irlet, B.; Halme, P. A fungal perspective on conservation biology. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ortega, A.; Lorite, J. Macrofungi diversity in cork-oak and holm-oak forests in Andalusia (southern Spain); an efficient parameter for establishing priorities for its evaluation and conservation. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2007, 2, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azul, A.M.; Castro, P.; Sousa, J.P.; Freitas, H. Diversity and fruiting patterns of ectomycorrhizal and saprobic fungi as indicators of land-use severity in managed woodlands dominated by Quercus suber—A case study from southern Portugal. Can. J. Res. 2009, 39, 2404–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández, A.; Sánchez, S.; García, P.; Sánchez, J. Macrofungal diversity in an isolated and fragmented Mediterranean Forest ecosystem. Plant. Biosyst. 2019, 154, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A. Diversidad Macrofúngica del Monte de la Orbada (Salamanca, España), un Ecosistema Forestal Mediterráneo Aislado y Fragmentado. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, G.; Manjón, J.L.; Álvarez-Jiménez, J. Los hongos y el cambio climático. In Los Bosques y la Biodiversidad frente al Cambio Climático: Impactos, Vulnerabilidad y Adaptación en España; Herrero, A., Zavala, M.A., Eds.; Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain; pp. 129–135.

- Perini, C.; Barluzzi, C.; De Dominicis, V. Seasonal fruit body production of macrofungi in Mediterranean vegetation. Bocconea 1996, 5, 359–373. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, L.; Büntgen, U.; Egli, S.; Gange, A.C.; Heegaard, E.; Kirk, P.M.; Mohammad, A.; Kauserud, H. Climate variation effects on fungal fruiting. Fungal Ecol. 2014, 10, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, C.; Heegaard, E.; Høiland, K.; Senn-Irlet, B.; Kuyper, T.W.; Krisai-Greilhuber, I.; Kirk, P.M.; Heilmann-Clausen, J.; Gange, A.C.; Egli, S.; et al. Explaining European fungal fruiting phenology with climate variability. Ecology 2018, 99, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jarvis, S.G.; Holden, E.M.; Taylor, A.F.S. Rainfall and temperature effects on fruit body production by stipitate hydnoid fungi in Inverey Wood, Scotland. Fungal Ecol. 2017, 29, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágreda, T.; Águeda, B.; Olano, J.M.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Fernández-Toirán, M. Increase evapotranspiration demand in a Mediterranean climate might cause a decline in fungal yields under global warming. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 3499–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salerni, E.; Laganà, A.; Perini, C.; Loppi, S.; Dominicis, V.D. Effects of temperature and rainfall on fruiting of macrofungi in oak forests of the Mediterranean area. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2002, 50, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágreda, T.; Águeda, B.; Fernández-Toirán, M.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Òlano, J.M. Long-term monitoring reveals a highly structured interspecific variability in climatic control of sporocarp production. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2016, 223, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azul, A.M.; Mendes, S.M.; Sousa, J.P.; Freitas, H. Fungal fruitbodies and soil macrofauna as indicators of land use practices on soil biodiversity in Montado. Agroforest. Syst. 2011, 82, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doveri, F. Occurrence of coprophilous Agaricales in Italy, new records, and comparisons with their European and extraeuropean distribution. Mycosphere 2010, 1, 103–140. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M.J. Diversity and occurrence of coprophilous fungi. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Dios, R.; Benito-Garzón, M.; Sainz-Ollero, H. Present and future extension of the Iberian submediterranean territories as determined from the distribution of marcescent oaks. Plant. Ecol. 2009, 204, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Quintano, P.; Caudullo, G.; de Rigo, D. Quercus pyrenaica in Europe: Distribution, habitat, usage and threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species, 1st ed.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publ. Off. EU: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 158–159. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, G.; López-Díaz, M.L. The Dehesa: The Most Extensive Agroforestry System in Europe. In Agroforestry Systems as a Technique for Sustainable Land Management, 1st ed.; Mosquera-Losada, M.R., Fernández-Lorenzo, J.L., Rigueiro-Rodríguez, A., Eds.; Unicopia: Lugo, Spain, 2009; pp. 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Zotti, M.; Pautasso, M. Macrofungi in Mediterranean Quercus ilex woodlands: Relations to vegetation structure, ecological gradients and higher-taxon approach. Czech. Mycol. 2013, 65, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, M.; Oria-de-Rueda, J.A.; Martín-Pinto, P. Post-fire fungal succession in a Mediterranean ecosystem dominated by Cistus ladanifer L. Ecol. Manag 2013, 289, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, A.; Salerni, E.; Barluzzi, C.; Perini, C.; De Dominicis, V. Macrofungi as long-term indicators of forest health and management in central Italy. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2020, 23, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Azul, A.M.; Nunes, J.; Ferreira, I.; Coelho, A.S.; Veríssimo, P.; Trovão, J.; Campos, A.; Castro, P.; Freitas, H. Valuing native ectomycorrhizal fungi as a Mediterranean forestry component for sustainable and innovative solutions. Botany 2014, 92, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágreda, T.; Cisneros, Ó.; Águeda, B.; Fernández-Toirán, L.M. Age class influence on the yield of edible fungi in a managed Mediterranean forest. Mycorrhiza 2014, 24, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egli, S. Mycorrhizal mushroom diversity and productivity—An indicator of forest health? Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jönsson, M.T.; Ruete, A.; Kellner, O.; Gunnarsson, U.; Snäll, T. Will forest conservation areas protect functionally important diversity of fungi and lichens over time? Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 2547–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, A.; Agbowo, J.; Bruns, T.D. Detection of plot-level changes in ectomycorrhizal communities across years in an old-growth mixed-conifer forest. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, H.; Jonsson, B.G. Nested plant and fungal communities; the importance of area and habitat quality in maximizing species capture in boreal old-growth forests. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 112, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, A.; Genney, D.R.; Heilmann-Clausen, J. Developing a comprehensive strategy for fungal conservation in Europe: Current status and future needs. Fungal Ecol. 2010, 3, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, A.O.; Borges, J.G. Designing decision support tools for Mediterranean forest ecosystems management: A case study in Portugal. Ann. Sci. 2005, 62, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molina, J.R.; Rodríguez y Silva, F.; Herrera, M.A. Integrating economic landscape valuation into Mediterranean territorial planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 56, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorestani, E.Z.; Kamkar, B.; Razaci, S.E.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A. Modeling and mapping diversity of pathogenic fungi of wheat fields using geographic information systems (GIS). J. Crop Prot. 2013, 54, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Health Status | Species Richness | Production Fruit Bodies | Preservation Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Health | Value | N species | Values | Carpophores | Value | Estimation |

| 3 | Optimum | 3 | Very high | 2 | High | 8–7 | Optimum |

| 2 | Good | 2 | High | 1 | Medium | 6–5 | Good |

| 1 | Favourable | 1 | Medium | 0 | Low | 4–3 | Suitable |

| 0 | Poor | 0 | Low | 2–1 | Poor | ||

| 0 | Not favourable | ||||||

| VEGETATION UNITS | EU HABITAT NAME | EU_CODE | PRIORITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holm oak dehesas | Pseudo-steppe with grasses and annuals of the Thero-Brachypodietea | 6220 | * |

| Endemic oro-Mediterranean heaths with gorse | 4090 | Np | |

| Dehesas with evergreen Quercus spp. | 6310 | Np | |

| Mixed dehesas of holm oak and Pyrenean oak | Pseudo-steppe with grasses and annuals of the Thero-Brachypodietea | 6220 | * |

| Endemic oro-Mediterranean heaths with gorse | 4090 | Np | |

| Dehesas with evergreen Quercus spp. | 6310 | Np | |

| Galicio-Portuguese oak woods with Quercus robur and Quercus pyrenaica | 9230 | Np | |

| Mixed dehesas of Pyrenean oak and holm oak | Pseudo-steppe with grasses and annuals of the Thero-Brachypodietea | 6220 | * |

| Mediterranean tall humid herb grasslands of the Molinio-Holoschoenion. | 6420 | Np | |

| Endemic oro-Mediterranean heaths with gorse | 4090 | Np | |

| Dehesas with evergreen Quercus spp. | 6310 | Np | |

| Galicio-Portuguese oak woods with Quercus robur and Quercus pyrenaica | 9230 | Np | |

| Pseudo-steppe with grasses and annuals of the Thero-Brachypodietea | 6220 | * | |

| Mediterranean tall humid herb grasslands of the Molinio-Holoschoenion. | 6420 | Np |

| Number sps | Tmax | Tmin | Tmean | Dif. Temp | Rainfall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n carpophores | 0.8437 ** | −0.2133 | 0.1926 | −0.1001 | −0.3791 | 0.4136 * |

| Number sps | −0.4502 * | −0.0063 | −0.3346 | −0.5363 ** | 0.5358 ** |

| Vegetation Unit | Plot | N sps | Fungal Lifestyle (%) | N Fruit Bodies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saprophte | Symbiotic | Parasite | ||||

| Culture | 1 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Grasslands | 6 | 16 | 59 | 41 | 0 | 240 |

| 14 | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 90 | |

| 16 | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 60 | |

| 20 | 11 | 91 | 9 | 0 | 165 | |

| HO dehesas | 2 | 13 | 62 | 38 | 0 | 195 |

| 3 | 24 | 71 | 29 | 0 | 465 | |

| 4 | 33 | 76 | 24 | 0 | 555 | |

| 10 | 35 | 70 | 30 | 0 | 645 | |

| 12 | 21 | 54 | 46 | 0 | 360 | |

| 13 | 49 | 76 | 24 | 0 | 930 | |

| 17 | 82 | 68 | 31 | 1 | 1905 | |

| 18 | 56 | 51 | 46 | 3 | 1095 | |

| 19 | 36 | 69 | 29 | 2 | 675 | |

| HO mixed dehesas | 5 | 39 | 89 | 9 | 2 | 645 |

| 8 | 12 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 180 | |

| 11 | 23 | 78 | 22 | 0 | 345 | |

| 15 | 18 | 47 | 48 | 5 | 285 | |

| PO mixed dehesas | 7 | 21 | 83 | 17 | 0 | 360 |

| 9 | 51 | 85 | 13 | 2 | 930 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García Jiménez, P.; Fernández Ruiz, A.; Sánchez Sánchez, J.; Rodríguez de la Cruz, D. Mycological Indicators in Evaluating Conservation Status: The Case of Quercus spp. Dehesas in the Middle-West of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 10442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410442

García Jiménez P, Fernández Ruiz A, Sánchez Sánchez J, Rodríguez de la Cruz D. Mycological Indicators in Evaluating Conservation Status: The Case of Quercus spp. Dehesas in the Middle-West of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain). Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410442

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía Jiménez, Prudencio, Abel Fernández Ruiz, José Sánchez Sánchez, and David Rodríguez de la Cruz. 2020. "Mycological Indicators in Evaluating Conservation Status: The Case of Quercus spp. Dehesas in the Middle-West of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain)" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410442

APA StyleGarcía Jiménez, P., Fernández Ruiz, A., Sánchez Sánchez, J., & Rodríguez de la Cruz, D. (2020). Mycological Indicators in Evaluating Conservation Status: The Case of Quercus spp. Dehesas in the Middle-West of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain). Sustainability, 12(24), 10442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410442