Disaster Risk Reduction in Bushfire Prone Areas: Challenges for an Integrated Land Use Planning Policy Regime

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Cross-Sectoral Synergies—Rise of an Integrated Approach to Disaster Risk Reduction

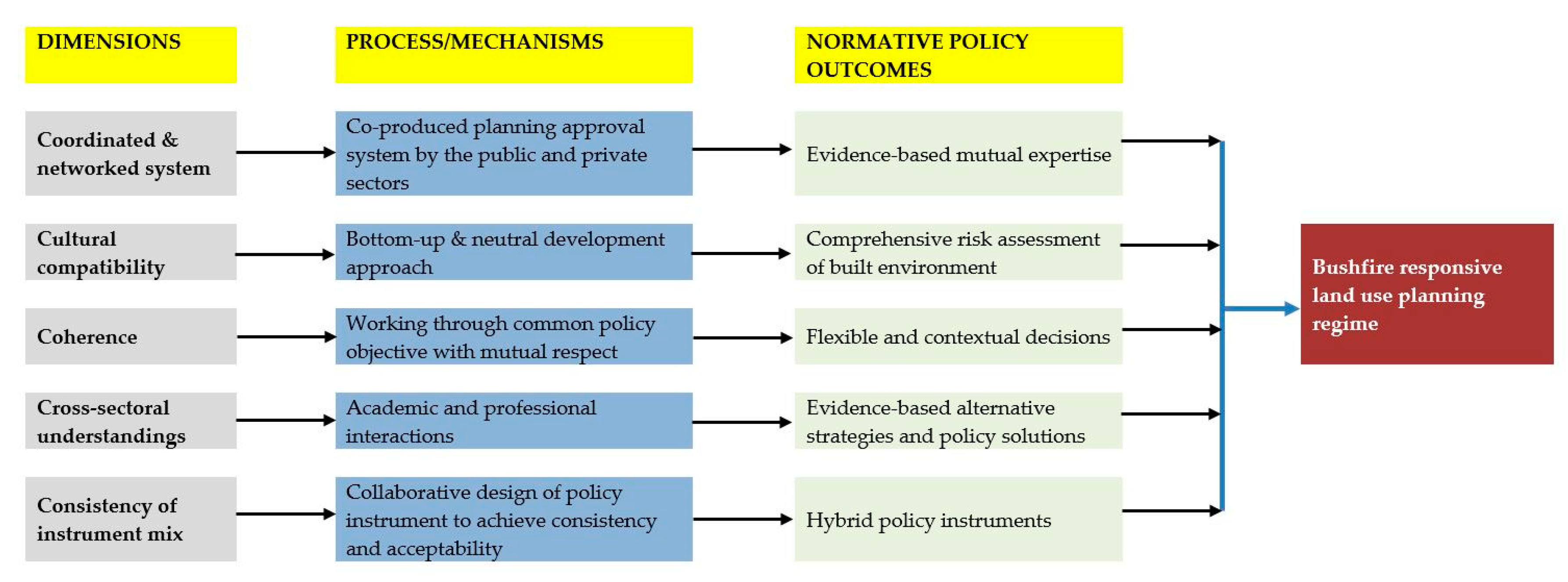

2.2. Defining Policy Integration

2.3. Conditions that Enable and Constrain Policy Integration

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. The Emergence of an Integrated Policy Regime for “Bushfire Protection”

4.2. The Challenges of Policy Integration for Planning in Bushfire Prone Areas

4.2.1. Coordinated Subsystem Interaction

4.2.2. Cultural Compatibility

“bushfire risk should have been considered in all planning decisions…but it wasn’t… No-one was enforcing it… the guidelines talked about local government designating bushfire prone areas, which they didn’t do” (DFES). This situation, according to another interviewee, “was increasing the vulnerability of communities at risk” (DFES).

“…a lot of development in the past happened in vegetated areas where development should have NEVER ever happened from a bushfire point of view… At least there’s a check and balance now…it’s great for community protection” (Bushfire Consultant).

“DFES have a very strong command and control structure. Similar to the army, similar to the police. People should obey their orders and they should do what they want” (Local Government Planner).

the WAPC planning area is often quite pro-development… the development industry, which is incredibly powerful, has a huge amount of influence on government, promotes land development as economic growth… The state government certainly sees [land development] as a very strong economic driver for growth and for local governments it can be too (Local Government Planner).

“There’s a lot of vested interested in development, and preventing development at a local government level by designating any areas as bushfire prone [would result in] political backlash for [local governments], because [the developers] are often their local rate payers and voters” (DFES).

4.2.3. Coherence of Subsystem Goals

“to try and figure out what our shared goals would be. And that is ongoing…there’s goodwill there, but each agency is looking at its own patch.”

DFES’s role is to ensure that people and property are not put at any risk. For planning, though, in decision-making, we need to consider a whole raft of things. We need to consider the demand for housing. We need to consider risks including bushfire. But there’s a whole raft of risks, other environmental policies, and protection of vegetation is a key one for planners (DPLH).

“[Planners] are not responsible for the response when things go wrong… they won’t be the ones that get pulled out in front of the coronial inquiry…It’s DFES and DFES’ leadership that will be held accountable. But the actual problem was caused through planning decisions” (DFES).

4.2.4. Cross-Sectoral Understandings

“So, we have planners with no bushfire experience and then we have DFES staff, who are the reverse, they have a lot of technical expertise in the fire space and not so much in the planning space.”

So when I’ve questioned [DFES] on the assumptions and been told, ‘you’ll need this much amount of research to back that up before DFES will support that.’ And when I asked them what research supports their current position, they have none…so you start to question the integrity of the whole thing.

DFES doesn’t appear to have the expertise or resources to assess an alternative solution-so they can’t approve it… DFES is always going to be risk averse…it’s in their nature, they’re never going to go out on a limb and say, “Oh look, we don’t really understand this alternative solution, but yeah, it looks fine… go for it.”

“Let’s have a scientific basis for our mapping or a new methodology and that’s how we should proceed, not on any other basis.”

4.2.5. Consistency of Instrument Mix to Address Policy Goals

“They’ve brought it all back to central advice point. But what that also means is the people providing that advice are not familiar with the location.”

the crux of the development of the policy, and the guidelines is that the policy is developed under the Planning Development Act…So, even though the guidelines are co-badged, it can be frustrating because it’s not done under our regulation, it’s not done by our agency, the state planning policy is not out policy. So, our ability to influence the content is curtailed.

Our role is to assess the Bushfire Management Plan against the policy and the guidelines and provide advice—not back to the consultant, but to the decision maker—and it’s advice only. So, it’s not mandatory…We’re just one referral agency and planning proposals get referred to other organizations, environment and so forth.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharples, J.J.; Cary, G.J.; Fox-Hughes, P.; Mooney, S.; Evans, J.P.; Fletcher, M.-S.; Fromm, M.; Grierson, P.F.; McRae, R.; Baker, P. Natural hazards in Australia: Extreme bushfire. Clim. Chang. 2016, 139, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, S.M.; Sarre, A. Editorial: The 2019/20 Black Summer bushfires. Aust. For. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.M. Landscape fires as social disasters: An overview of ‘the bushfire problem’. Environ. Hazards 2005, 6, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Cochrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; DeFries, R.; Johnston, F.H.; Keeley, J.E.; Krawchuk, M.A.; et al. The human dimension of fire regimes on Earth. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 2223–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kornakova, M.; March, A.; Gleeson, B. Institutional Adjustments and Strategic Planning Action: The Case of Victorian Wildfire Planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2018, 33, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, A.; de Moraes, L.N.; Riddell, G.; Stanley, J.; van Delden, H.; Beilin, R.; Dovers, S.; Maier, H. Practical and Theoretical Issues: Integrating Urban Planning and Emergency Management: First Report for the Integrated Urban Planning for Natural Hazard Mitigation Project; Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, E.; Minnery, J. Bushfires and land use planning in peri-urban South East Queensland. Aust. Plan. 2015, 52, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintosh, A.; Foerster, A.; McDonald, J. Policy design, spatial planning and climate change adaptation: A case study from Australia. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 1432–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buti, T. Bushfire Planning and Policy Review: A Review into the Western Australian Framework for Planning and Development in Bushfire Prone Areas; Government of WA: Perth, Australia, 2019.

- March, A. Integrated Planning to Reduce Disaster Risks: Australian Challenges and Prospects. Built Environ. 2016, 42, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Mathiesen, C. Nine design features for bushfire risk reduction via urban planning. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2014, 29, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- March, A.; Rijal, Y. Interdisciplinary action in urban planning and building for bushfire: The Victorian case. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2015, 30, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Mathiesen, C.; Ruane, S.; March, A. Integrating wildfire risk management and spatial planning—A historical review of two Australian planning systems. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, A.; Rijal, Y. Reducing Bushfire Risk by Planning and Design: A Professional Focus. Plan. Pract. Res. 2015, 30, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Mathiesen, C.; March, A. Establishing Design Principles for Wildfire Resilient Urban Planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2018, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, P. Urban planning and transport policy integration: The role of governance hierarchies and networks in London and Berlin. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trein, P.; Meyer, I.; Maggetti, M. The Integration and Coordination of Public Policies: A Systematic Comparative Review. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2019, 21, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren-Hamakers, I.J. Integrative environmental governance: Enhancing governance in the era of synergies. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbeck, R.; Steurer, R. Multi-sectoral strategies as dead ends of policy integration: Lessons to be learned from sustainable development. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2015, 34, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.; Howlett, M. Introduction: Understanding integrated policy strategies and their evolution. Policy Soc. 2009, 28, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Djalante, R.; Holley, C.; Thomalla, F.; Carnegie, M. Pathways for adaptive and integrated disaster resilience. Nat. Hazards 2013, 69, 2105–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Johannessen, Å. Meeting at the crossroads? Developing national strategies for disaster risk reduction and resilience: Relevance, scope for, and challenges to, integration. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 45, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D.; Buergelt, P. Risk, Transformation and Adaptation: Ideas for Reframing Approaches to Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- UNISDR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- UNIDSR. Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction-New York UNHQ Liason Officer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/46052_disasterriskreductioninthe2030agend.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Commonwealth of Australia. National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework; Affairs, D.O.H., Ed.; 2018. Available online: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/emergency/files/national-disaster-risk-reduction-framework.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Cumiskey, L.; Priest, S.J.; Klijn, F.; Juntti, M. A framework to assess integration in flood risk management: Implications for governance, policy, and practice. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Candel, J.J.L.; Biesbroek, R. Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sci. 2016, 49, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Metz, F.; Angst, M.; Fischer, M. Policy integration: Do laws or actors integrate issues relevant to flood risk management in Switzerland? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 61, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Lang, A. Policy integration: Mapping the different concepts. Policy Stud. 2017, 38, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.J.; Jochim, A.E. Policy Regime Perspectives: Policies, Politics, and Governing. Policy Studies J. 2013, 41, 426–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wison, C.A. Policy Regimes and Policy Change. J. Public Policy 2000, 20, 247–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, E.; Stead, D. Policy integration: What does it mean and how can it be achieved? A multi-disciplinary review. In Proceedings of the Berlin Conference on the Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change: Greening of Policies-Interlinkages and Policy Integration, Berlin, Germany, 3 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Briassoulis, H. Policy Integration for Complex Policy Problems: What, Why and How. In Proceedings of the Greening of Policies: Interlinkages and Policy Integration, Berlin, Germany, 3–4 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Underdal, A. Integrated marine policy: What? Why? How? Mar. Policy 1980, 4, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochim, A.E.; May, P.J. Beyond Subsystems: Policy Regimes and Governance. Policy Studies J. 2010, 38, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Vince, J.; Río González, P.D. Policy Integration and Multi-Level Governance: Dealing with the Vertical Dimension of Policy Mix Designs. Politics Gov. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vince, J. Integrated policy approaches and policy failure: The case of Australia’s Oceans Policy. Policy Sci. 2015, 48, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, J.; Pereira, L. Towards integrated food policy: Main challenges and steps ahead. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 73, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Rayner, J.; Goehler, D.; Heidbreder, E.; Perron-Welch, F.; Rukundo, O.; Verkooijen, P.; Wildburger, C. Overcoming the Challenges to Integration: Embracing Complexity in Forest Policy Design through Multi-Level Governance; IUFRO (International Union of Forestry Research Organizations) Secretariat: Wien, Austria, 2010; pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Adelle, C.; Russel, D. Climate Policy Integration: A Case of Déjà Vu? Environ. Policy Gov. 2013, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, J.J.L. The expediency of policy integration. Policy Studies 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Da Costa Canoquena, J.M. Reconceptualising policy integration in road safety management. Transp. Policy 2013, 25, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillard, J.J.; Heal, K.V.; Ball, T.; Reeves, A.D. Policy integration for adaptive water governance: Learning from Scotland’s experience. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 33, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D.; Meijers, E. Spatial Planning and Policy Integration: Concepts, Facilitators and Inhibitors. Plan. Theory Pract. 2009, 10, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.N.; Persson, A.S. Framework for analysing environmental policy integration. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2003, 5, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.; Howlett, M. Conclusion: Governance arrangements and policy capacity for policy integration. Policy Soc. 2009, 28, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burrows, N.; McCaw, L. Prescribed burning in southwestern Australian forests. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, e25–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Hughes, L.; Pearce, A. The Heat is on: Climate Change, Extreme Heat and Bushfire in Western Australia; Climate Change Council of Australia Ltd.: Sydney, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ruane, S. Applying the principles of adaptive governance to bushfire management: A case study from the South West of Australia. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, D. It’s all about mechanisms—What process-tracing case studies should be tracing. New Political Econ. 2016, 21, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahoney, J. Process Tracing and Historical Explanation. Secur. Studies 2015, 24, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience. Victoria and South Australia Ash Wednesday Bushfire, 1983. Available online: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/resources/bushfire-ash-wednesday-1983 (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Miller, S.; Carter, W.; Stephens, R. Report of the Bushfire Review Committee: On Bush Fire Disaster Preparedness and Response in Victoria, Australia, Following the Ash Wednesday Fires 16 February 1983; Government Printer: Melbourne, Australia, 1984.

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment and Conservation. Bushfires and the Australian Environment; Milton, P., Ed.; Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra, Australia, 1984.

- Norman, B.; Weir, J.K.; Sullivan, K.; Lavis, J. Planning and Bushfire Risk in a Changing Climate: Final Report for the Urban and Regional Planning Systems Project; Bushfire CRC: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- State Planning Commission. Planning for Better Bushfire Protection; Government of WA: Perth, Australia, 1989.

- State Planning Commission. Policy for Development Control 4.2: Planning for Hazards and Safety; Government of WA: Perth, Australia, 1991.

- Shire of Augusta-Margaret River. Shire of Augusta-Margaret River Rural Stategy; Shire of Augusta-Margaret River: Margaret River, Australia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- State of Western Australia. Planning for Bush Fire Protection Guidelines, 2nd ed.; Western Australian Planning Commission and the Fire and Emergency Services Authority: Perth, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Western Australia. A Shared Responsibility: The Report of the Perth Hills Bushfire February 2011 Review; Government of WA: Perth, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Western Australian Planning Commission. State Planning Policy 3.7: Planning in Bushfire Prone Areas; Western Australian Planning Commission: Perth, Australia, 2015.

- DFES. Map of Bush Fire Prone Areas. Available online: https://www.dfes.wa.gov.au/bushfire/bushfireproneareas/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Bosomworth, K. Climate change adaptation in public policy: Frames, fire management, and frame reflection. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2015, 33, 1450–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, M.A.; Batllori, E.; Bradstock, R.A.; Gill, A.M.; Handmer, J.; Hessburg, P.F.; Leonard, J.; McCaffrey, S.; Odion, D.C.; Schoennagel, T.; et al. Learning to coexist with wildfire. Nature 2014, 515, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, C.; Brooks, B.; Curnin, S.; Bearman, C. Enhancing Learning in Emergency Services Organisational Work. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2018, 77, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosomworth, K.; Owen, C.; Curnin, S. Addressing challenges for future strategic-level emergency management: Reframing, networking, and capacity-building. Disasters 2017, 41, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruane, S. Using a worldview lens to examine complex policy issues: A historical review of bushfire management in the South West of Australia. Local Environ. 2018, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosomworth, K. A discursive–institutional perspective on transformative governance: A case from a fire management policy sector. Environ. Policy Gov. 2018, 28, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buizer, M.; Kurz, T. Too hot to handle: Depoliticisation and the discourse of ecological modernisation in fire management debates. Geoforum 2016, 68, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heazle, M.; Tangney, P.; Burton, P.; Howes, M.; Grant-Smith, D.; Reis, K.; Bosomworth, K. Mainstreaming climate change adaptation: An incremental approach to disaster risk management in Australia. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 33, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kickert, W.J.M.; van Der Meer, F.-B. Small, Slow, and Gradual Reform: What can Historical Institutionalism Teach Us? Int. J. Public Adm. 2011, 34, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. Taking path dependence seriously: An historical institutionalist research agenda in planning history. Plan. Perspect. 2015, 30, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capoccia, G. When Do Institutions “Bite”? Historical Institutionalism and the Politics of Institutional Change. Comp. Political Studies 2016, 49, 1095–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Streeck, W.; Thelen, K. Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning in Perspective. Plan. Theory 2003, 2, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macintosh, A.; Mcdonald, J.; Foerster, A. Designing spatial adaptation planning instruments. In Applied Studies in Climate Adaptation; Palutikof, J.P., Boulter, S.L., Barnett, J., Rissik, D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2015; pp. 34–42. ISBN 9781118845011. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Enabling Condition | Constraining Condition | Key Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinated subsystem interaction | Political will and a government mode supportive of policy integration. | Lack of political support and a government favoring sector specialization. | Rode [16], Candel and Biesbroek [28], Rouillard et al. [44], Meijers and Stead [33], Briassoulis [34], Stead and Meijers [45] |

| Effective administrative, financial and legislative structures. | Administrative fragmentation, insufficient resources and inadequate legislation. | Rode [16], Briassoulis [34], Rouillard, Heal, Ball and Reeves [44], Nordbeck and Steurer [19], Metz, Angst and Fischer [29], Stead and Meijers [45] | |

| A lead subsystem and other committed subsystems. | Lack of leadership and subsystem commitment. | Briassoulis [34], Meijers and Stead [33], Rode [16], Stead and Meijers [45] | |

| Cultural Compatibility | Subsystems share similar worldviews. | Subsystems have diverging worldviews. | Briassoulis [34], Candel and Biesbroek [28], Metz, Angst and Fischer [29] |

| Subsystems have a collaborative culture and willingness to share decision-making. | Subsystems prefer sectorial specialization and retaining decision-making power. | Metz, Angst and Fischer [29], Nordbeck and Steurer [19], Cumiskey, Priest, Klijn and Juntti [27], Stead and Meijers [45] | |

| Subsystems share a common understanding of the policy problem/s. | Subsystems frame the policy problem/s differently. | [27], Nilsson and Persson [46], Candel and Biesbroek [28], Stead and Meijers [45] | |

| Coherence of sectorial goals | Congruent and compatible policy goals. | Incoherent goals and an absence of an overarching strategic vision. | Candel and Biesbroek [28], Metz, Angst and Fischer [29], Rouillard, Heal, Ball and Reeves [44], Candel and Pereira [39], Meijers and Stead [33], Cumiskey, Priest, Klijn and Juntti [27], Rayner and Howlett [20], Briassoulis [34] |

| Subsystems’ specific specialized responsibilities align with overarching policy regime goals. | Misalignment of subsystems’ specialized responsibilities with overarching policy regime goals. | Meijers and Stead [33], Briassoulis [34], Cumiskey, Priest, Klijn and Juntti [27] | |

| All relevant subsystems of the regime are involved in developing policy goals. | Failure to involve all relevant subsystems in developing policy goals. | Stead and Meijers [45], Candel and Biesbroek [28] | |

| Cross-sectoral understandings | Policy actors willing to engage with new knowledge, and information is shared across subsystems. | A reluctance of policy actors to embrace new knowledge, and information and data sharing is constrained. | Cumiskey, Priest, Klijn and Juntti [27], Briassoulis [34], Stead and Meijers [45] |

| Various opportunities available for cross-disciplinary learning for actors. | Limited opportunities for actors to gain knowledge outside of their core discipline. | Metz, Angst and Fischer [29], Cumiskey, Priest, Klijn and Juntti [27], Metz, Angst and Fischer [29], Briassoulis [34] | |

| New knowledge and policy frames produced through instrument co-design and policy learning processes. | Instruments designed by the dominant subsystem with limited opportunities for policy learning and knowledge sharing. | Cumiskey et al. [27], Briassoulis [34], Rayner and Howlett [47] | |

| Consistency of instrument mix | Policy instruments are compatible with the overarching policy goals. | Instruments are inconsistent and fail to address the overarching regime policy goals. | Rayner and Howlett [20], Briassoulis [34], Candel and Biesbroek [28], Trein, Meyer and Maggetti [17] |

| Instruments mix cuts across the subsystems and merges the professional expertise of subsystems. | The instrument mix is the result of policy layering and characterized by duplication, gaps and failure. | Candel and Biesbroek [28], Trein, Meyer and Maggetti [17] Howlett, Vince and Pablo del [37] | |

| Flexible instruments with review and monitoring mechanisms that allow for readjustment and adaptation. | Rigid policy instruments with inadequate review and monitoring mechanisms to enable readjustment and adaptation. | Meijers and Stead [33], Briassoulis [34],Stead and Meijers [45] |

| Sector Organization/Policy Subsystem | Number of Interviewees |

|---|---|

| Department of Fire and Emergency Services (DFES) | 3 |

| Department of Planning Lands and Heritage (DPLH) | 2 |

| Western Australian Local Government Association (WALGA) | 1 |

| Bushfire Consultants | 4 |

| Local Government Planners | 6 |

| Local Government Senior Executive Staff | 2 |

| Local Government Environmental Managers | 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruane, S.; Swapan, M.S.H.; Babb, C. Disaster Risk Reduction in Bushfire Prone Areas: Challenges for an Integrated Land Use Planning Policy Regime. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410496

Ruane S, Swapan MSH, Babb C. Disaster Risk Reduction in Bushfire Prone Areas: Challenges for an Integrated Land Use Planning Policy Regime. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410496

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuane, Simone, Mohammad Shahidul Hasan Swapan, and Courtney Babb. 2020. "Disaster Risk Reduction in Bushfire Prone Areas: Challenges for an Integrated Land Use Planning Policy Regime" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410496

APA StyleRuane, S., Swapan, M. S. H., & Babb, C. (2020). Disaster Risk Reduction in Bushfire Prone Areas: Challenges for an Integrated Land Use Planning Policy Regime. Sustainability, 12(24), 10496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410496