Communication Strategies for the 2030 Agenda Commitments: A Multivariate Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptual Framework and Research Hypothesis

1.1.1. The 2030 Agenda as a Point of Convergence for CSR Actions

1.1.2. Communication Strategies on SDGs: Legitimacy Theory vs. Impression Management Theory

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Sample

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.1.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Degree of Commitment to the SDGs

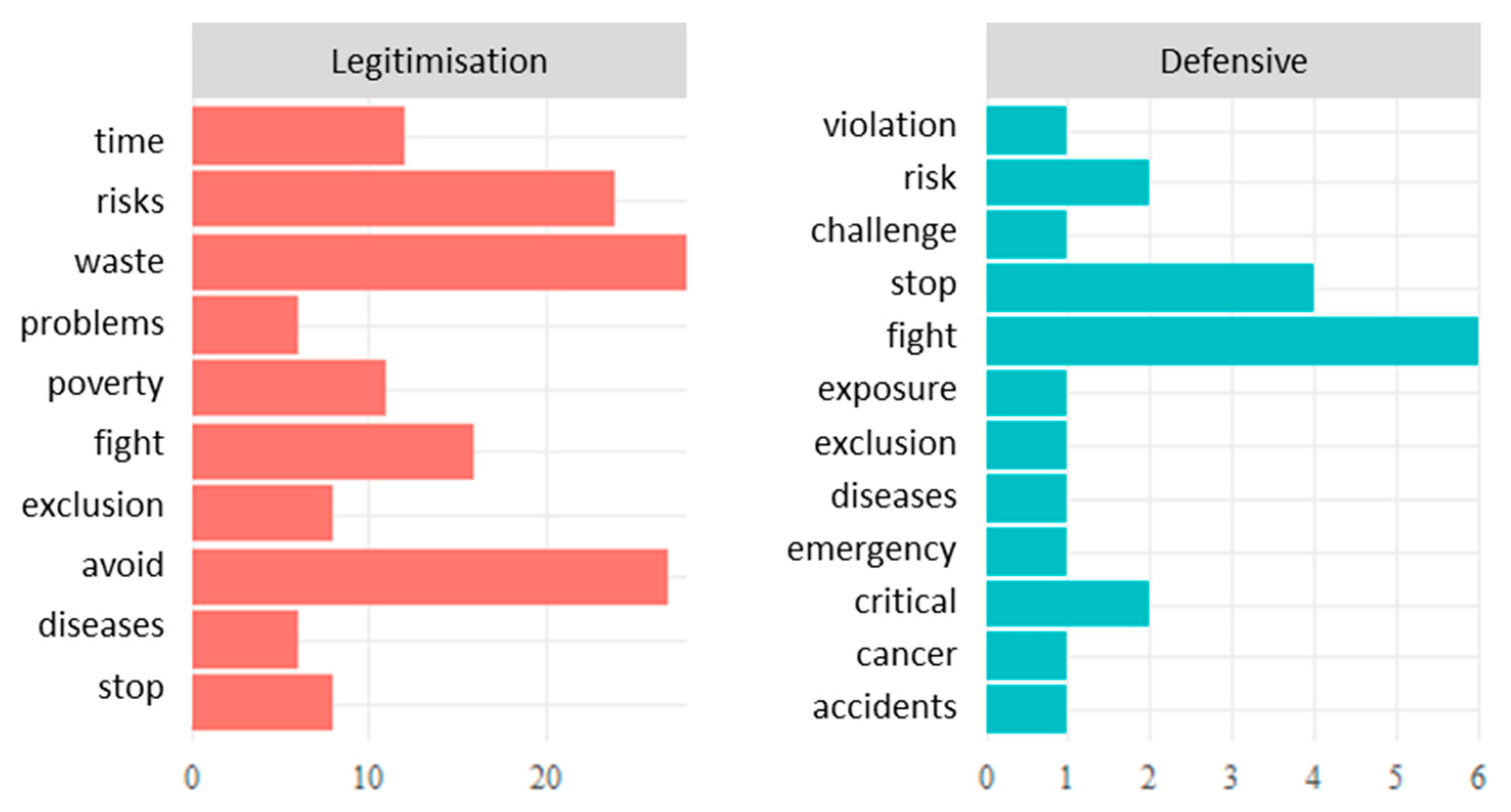

3.1.2. Descriptive Textual Analysis

3.1.3. Descriptive Textual Analysis at the Sector Level

3.2. Results Strategies for Legitimation and Impression Management

3.2.1. Overall Results

3.2.2. Sector Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Aibar-Guzmán, B.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. “Sell” recommendations by analysts in response to business communication strategies concerning the Sustainable Development Goals and the SDG compass. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Deegan, C. The public disclosure of environmental performance information—A dual test of media agency setting theory and legitimacy theory. Account. Bus. Res. 1998, 29, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value. How to Reinvent Capitalism—And Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Aibar-Guzmán, B.; Aibar-Guzmán, C. Do institutional investors drive corporate transparency regarding business contribution to the sustainable development goals? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2019–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Implications of Organizational Legitimacy for Corporate Social Performance and Disclosure. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-implications-of-Organizational-Legitimacy-for-Lindblom/98df7ea8cd1d19bf94d0a235f6385d71ed253360 (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The legitimising effects of social and environmental disclosures—A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, M.J.; Patten, D.M. Securing organizational legitimacy: An experimental design case examining the impact of environmental disclosures. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 372–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Gómez-Miranda, M.-E.; David, F.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. The explanatory effect of CSR committee and assurance services on the adoption of the IFC performance standards, as a means of enhancing corporate transparency. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 10, 773–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Gómez-Miranda, M.; David, F.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. Board independence and GRI-IFC performance standards: The mediating effect of the CSR committee. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Pollach, I. The Perils and Opportunities of Communicating Corporate Ethics. J. Mark. Manag. 2005, 21, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbach, K.D. Organizational Perception Management. Res. Organ. Behav. 2003, 25, 297–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Ferrero, J.; Suárez-Fernández, O.; García-Sánchez, I.-M. Obfuscation versus enhancement as corporate social responsibility disclosure strategies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbach, K.D.; Sutton, R.I. Acquiring organizational legitimacy through illegitimate actions: A marriage of institutional and impression management theories. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 699–738. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Suárez-Fernández, O.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Female directors and impression management in sustainability reporting. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Crit. Sociol. 2008, 34, 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Michelon, G.; Patten, D.M. Enhancement and obfuscation through the use of graphs in sustainability reports: An international comparison. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2012, 3, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Heras, I.; Brotherton, M.-C. Assessing and Improving the Quality of Sustainability Reports: The Auditors’ Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Brotherton, M.-C.; Bernard, J. Ethical Issues in the Assurance of Sustainability Reports: Perspectives from Assurance Providers. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1111–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Araújo-Bernardo, C. What colour is the corporate social responsibility report? Structural visual rhetoric, impression management strategies, and stakeholder engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Lülfs, R. Legitimizing Negative Aspects in GRI-Oriented Sustainability Reporting: A Qualitative Analysis of Corporate Disclosure Strategies. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkl-Davies, D.M.; Brennan, N.M.; McLeay, S.J. Impression management and retrospective sense-making in corporate narratives. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2011, 24, 315–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVinney, T.M. Is the Socially Responsible Corporation a Myth? The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; García-Sánchez, A. Corporate Social Responsibility during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesi, R.; Houston, J.F.; Naranjo, A. Corporate socially responsible investments: CEO altruism, reputation, and shareholder interests. J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 26, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölbel, J.F.; Busch, T.; Jancso, L.M. How Media Coverage of Corporate Social Irresponsibility Increases Financial Risk. Strategy Manag. J. 2017, 38, 2266–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. The effect of institutional ownership and ownership dispersion on eco-innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 158, 120173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Dou, J.; Jia, S. A meta-analytic review of corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: The moderating effect of contextual factors. Bus. Soc. 2015, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medne, A.; Lapiņa, I. Sustainability and Continuous Improvement of Organization: Review of Process-Oriented Performance Indicators. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeMartini, P. Why and How Women in Business Can Make Innovations in Light of the Sustainable Development Goals. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balcerzak, A.P.; Pelikánová, R.M. Projection of SDGs in Codes of Ethics—Case Study about Lost in Translation. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor-Esteban, V.; Galindo-Villardón, M.P.; David, F. Study of the Importance of National Identity in the Development of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices: A Multivariate Vision. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silvius, G.; Schipper, R. Planning Project Stakeholder Engagement from a Sustainable Development Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Maddaloni, F.; Derakhshan, R.; Maddaloni, D. A Leap from Negative to Positive Bond. A Step towards Project Sustainability. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations a Resource Dependence Perspective; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, J.; Pfeffer, J. Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1975, 18, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, A.; Cataldo, A.J.; Rowlands, J. A multi-case investigation of environmental legitimation in annual reports. Adv. Environ. Account. Manag. 2004, 1, 45–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Villiers, C.; Van Staden, C.J. Where firms choose to disclose voluntary environmental information. J. Account. Public Policy 2011, 30, 504–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Maximizing Business Returns to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of CSR Communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siueia, T.T.; Wang, J. La asociación entre las Actividades de Responsabilidad Social Corporativa y la calidad de los ingresos: Evidencia de la industria extractiva. Rev. Contab. Span. Account. Rev. 2019, 22, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.; Rahman, A. Web-based impression management? Salient features for CSR disclosure prominence. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 99–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Hussain, N.; Khan, S.-A.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Do Markets Punish or Reward Corporate Social Responsibility Decoupling? Bus. Soc. 2020, 2020d, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 1036–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M. Corporate social responsibility as strategic auto-communication: On the role of external stakeholders for member identification. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Fondevila, M.; Moneva-Abadía, J.M.; Scarpellini, S. Divulgación ambiental y la interrelación de la ecoinnovación. El caso de las empresas españolas. Rev. Contab. Span. Account. Rev. 2019, 22, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tata, J.; Prasad, S. CSR Communication: An Impression Management Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 132, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, D.; Boiral, O. The quality of sustainability reports and impression management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. A commentary on: Corporate social responsibility reporting and reputation risk management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, B.A. Obfuscation, Textual Complexity and the Role of Regulated Narrative Accounting Disclosure in Corporate Governance. J. Manag. Gov. 2003, 7, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzolan, S.; Cho, C.H.; Michelon, G. Impression Management and Organizational Audiences: The Fiat Group Case. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 126, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa Concordia Disaster. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Costa_Concordia_disaster (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Merkl-Davies, D.M.; Brennan, N.M. Discretionary disclosure strategies in corporate narratives: Incremental information or impression management? J. Account. Lit. 2007, 26, 116–194. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C.H.; Laine, M.; Roberts, R.W.; Rodrigue, M. Organized hypocrisy, organizational façades, and sustainability reporting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2015, 40, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Pilonato, S.; Ricceri, F.; Roberts, R.W. Behind camouflaging: Traditional and innovative theoretical perspectives in social and environmental accounting research. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, I.; Lodhia, S.; Narayan, A.K. Value creation attempts via photographs in sustainability reporting: A legitimacy theory perspective. Meditari Account. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.; Narayan, A.K.; Ali, I. Photographs depicting CSR: Captured reality or creative illusion? Pac. Account. Rev. 2019, 31, 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrasky, S. Carbon footprints and legitimation strategies: Symbolism or action? Account. Audit. Account. J. 2012, 25, 174–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, J. In visible intangibles: Visual portraits of the business elite. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, D.; Boiral, O. GHG Reporting and Impression Management: An Assessment of Sustainability Reports from the Energy Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, V.D. The disclosure of industrial greenhouse gas emissions: A critical assessment of corporate sustainability reports. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 29–30, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F. Beyond the Bounded Instrumentality in Current Corporate Sustainability Research: Toward an Inclusive Notion of Profitability. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H. Legitimation strategies used in response to environmental disaster: A French case study of Total SA’s Erika and AZF incidents. Eur. Account. Rev. 2009, 18, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, P.; Giacalone, R.A.; Riordan, C.A. Impression Management in Organizations: Theory, Measurement, Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Gardner, W.L.; Paolillo, J.G.P. A taxonomy of organizational impression management tactics. Adv. Compet. Res. 1999, 7, 108–130. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Martínez-Ferrero, J.; Garcia-Benau, M.-A. Integrated reporting: The mediating role of the board of directors and investor protection on managerial discretion in munificent environments. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farneti, F.; Casonato, F.; Montecalvo, M.; De Villiers, C. The influence of integrated reporting and stakeholder information needs on the disclosure of social information in a state-owned enterprise. Meditari Account. Res. 2019, 27, 556–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L.K.; Arvidsson, A.; Nielsen, F.A.; Colleoni, E.; Etter, M. Good Friends, Bad News—Affect and Virality in Twitter. In Cyberspace Data and Intelligence, and Cyber-Living, Syndrome, and Health; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, M.P. Una alternativa de representacion simultanea: HJ-Biplot. Qüestiió Quad. Estad. Investig. Oper. 1986, 10, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M.; Nielsen, K.U. The ‘Catch 22’ of communicating CSR: Findings from a Danish study. J. Mark. Commun. 2008, 14, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.C.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L.; Vohs, K.; Mogilner, C. Non-Profits are Seen as Warm and For-Profits as Competent: Firm Stereotypes Matter. SSRN Electron. J. 2010, 37, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Frost, G.R. Accessibility and functionality of the corporate web site: Implications for sustainability reporting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Companies by Sector | Frequency | % | Frequency | % |

| Consumer Goods | 29 | 18.1 | 10 | 14.5 |

| Basic Materials | 43 | 26.9 | 18 | 26.1 |

| Oil and Energy | 15 | 9.3 | 11 | 15.9 |

| Consumer Services | 21 | 13.1 | 10 | 14.5 |

| Financial Services | 24 | 15.0 | 12 | 17.4 |

| Real Estate Services | 18 | 11.3 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Technology and Telecommunications | 10 | 6.3 | 7 | 10.1 |

| Total | 160 | 100.0 | 69 | 100.0 |

| Words by Industry | Different Words | Words | Companies | Average Number of Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Goods | 1020 | 2018 | 10 | 201.80 |

| Basic Materials | 1573 | 3815 | 18 | 211.94 |

| Oil and Energy | 993 | 1964 | 11 | 178.55 |

| Consumer Services | 1136 | 1965 | 10 | 196.50 |

| Financial Services | 1532 | 3539 | 12 | 294.92 |

| Real Estate Services | 141 | 180 | 1 | 180.00 |

| Technology and Telecommunications | 867 | 1424 | 7 | 203.43 |

| Total | 7262 | 14,905 | 69 | 209.59 |

| Axis | Eigenvalue | % Variance | % Accumulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 | 56.52 | 26.17 | 26.17 |

| Axis 2 | 54.37 | 25.17 | 51.34 |

| Axis 3 | 35.32 | 16.35 | 67.69 |

| Axis 4 | 28.34 | 13.12 | 80.81 |

| Axis 5 | 22.84 | 10.57 | 91.38 |

| Axis 6 | 18.61 | 8.62 | 100.00 |

| Variable | Axis 1 | Axis 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer Goods | 3 | 608 |

| Basic Materials | 459 | 5 |

| Oil and Energy | 554 | 9 |

| Consumer Services | 177 | 281 |

| Financial Services | 114 | 223 |

| Technology and Telecommunications | 262 | 385 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Amor-Esteban, V.; Galindo-Álvarez, D. Communication Strategies for the 2030 Agenda Commitments: A Multivariate Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410554

García-Sánchez I-M, Amor-Esteban V, Galindo-Álvarez D. Communication Strategies for the 2030 Agenda Commitments: A Multivariate Approach. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410554

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Sánchez, Isabel-María, Víctor Amor-Esteban, and David Galindo-Álvarez. 2020. "Communication Strategies for the 2030 Agenda Commitments: A Multivariate Approach" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410554