Harnessing Corporate Sustainability Decision-Making Complexity: A Field Study of Complementary Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To provide a global picture of research into the sustainable supplier selection problem;

- To propose a new decision-making tool using combined AHP-DEMATEL-BN methods in an uncertain environment for evaluating and selecting sustainable suppliers;

- To validate the proposed approach in a real case and provide some managerial and research insights.

2. Literature Review

- The three techniques are frequently used in the literature and combined with other techniques that help to build on each other’s capabilities, overcoming some of their weaknesses.

- Despite the large number of studies proposing the use of AHP, DEMATEL and BN (Table 1), there is no study that considers sustainability criteria and examines the interrelationships among them in order to evaluate and select the right supplier using AHP-DEMATEL-BN simultaneously.

- There is still limited literature that illustrates the use of these methods through a case example for the sustainable supplier selection problem in a practical and actual manufacturing setting.

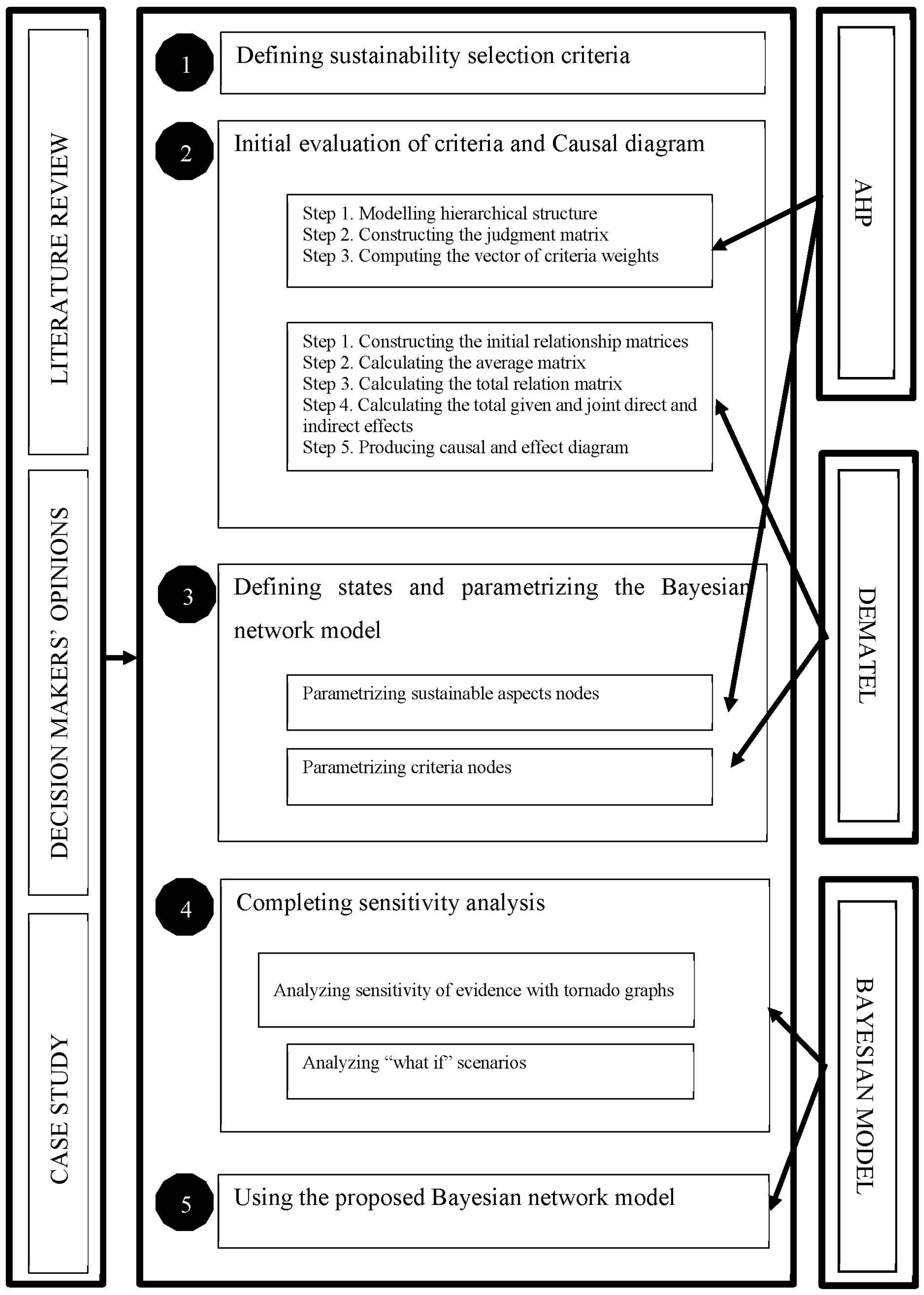

3. The AHP-DEMATEL-BN Approach

- AHP evaluates the decision problems hierarchically by decomposing the complex problem into simpler subproblems, while the DEMATEL approach effectively evaluates decision-makers’ priorities at an initial level of decision-making. The supplier selection problem is decomposed to three goal levels, sustainable aspects and criteria. The importance weights of each sustainability dimension for decision makers are calculated using AHP. Then, these weights are integrated into a BN model.

- AHP does not consider relations among the evaluation criteria and assumes that they are independent. DEMATEL’s complementarity deals with this issue. Using DEMATEL, the causal relations among the evaluation criteria are analyzed and the initial causal graph is proposed to build the BN model.

- AHP and DEMATEL cannot be used alone as a decision-making tool to explicitly evaluate uncertainties and limited information. However, BNs have dominant properties for making probabilistic calculations despite the unknown information for some evaluation criteria.

- By combining AHP, DEMATEL and BN, we model the sustainable supplier performance from both short-term and long-term viewpoints.

3.1. Defining Sustainability Selection Criteria

- Overall costs (Eco1): This is a key criterion for evaluating a supplier because it dictates the total supply chain cost. This criterion includes transportation and purchasing costs.

- Quality of product (Eco2): This is the capability of products and material to meet the quality standards for production processes. Scrap rate is used to determine the quality of delivered parts in this study.

- Quality of service (Eco3): This criterion represents the ability of a partner to satisfy demand and perform various functions in terms of delivery.

- Reducing pollution (Env1): The total emitted CO2 by each supplier is used to determine their performance regarding reducing pollution.

- Resource consumption (Env2): Suppliers are evaluated regarding the amount of energy consumption. Building energy performance indicator in kwh/m2/year is used.

- Environmental management system (Env3): The level of effort to reduce environmental impact is measured by an environmental management system certification (ISO 14001) (https://nbs.net/p/3-ways-smes-can-tackle-iso-14001-70c12e6b-8c15-428b-9c15-c248f08cf098). ISO 14001 has a progressive approach that breaks down the certification process into three successive levels.

- Employment practices (Soc1): This critical criterion defines the total commitment of a potential partner regarding employment. It refers to the level of temporary workers in this study.

- Health and safety (Soc2): Partners in the sustainable supply chain should aim to improve activities by minimizing health and safety incidents and implementing security practices to enhance the quality of life for employees. Number of incidents per year per 1000 employees is considered to evaluate the supplier.

- Responsibility to stakeholders and community (Soc3): Funds given by a supplier for educational, charitable purposes and to support community projects and social programs could be considered when evaluating suppliers in terms of social responsibility.

3.2. Initial Criteria Evaluation and Causal Diagram Construction

3.2.1. AHP for Sustainability Dimension Weights and Hierarchical Structure

3.2.2. DEMATEL for Direct Relations and Causal Graph

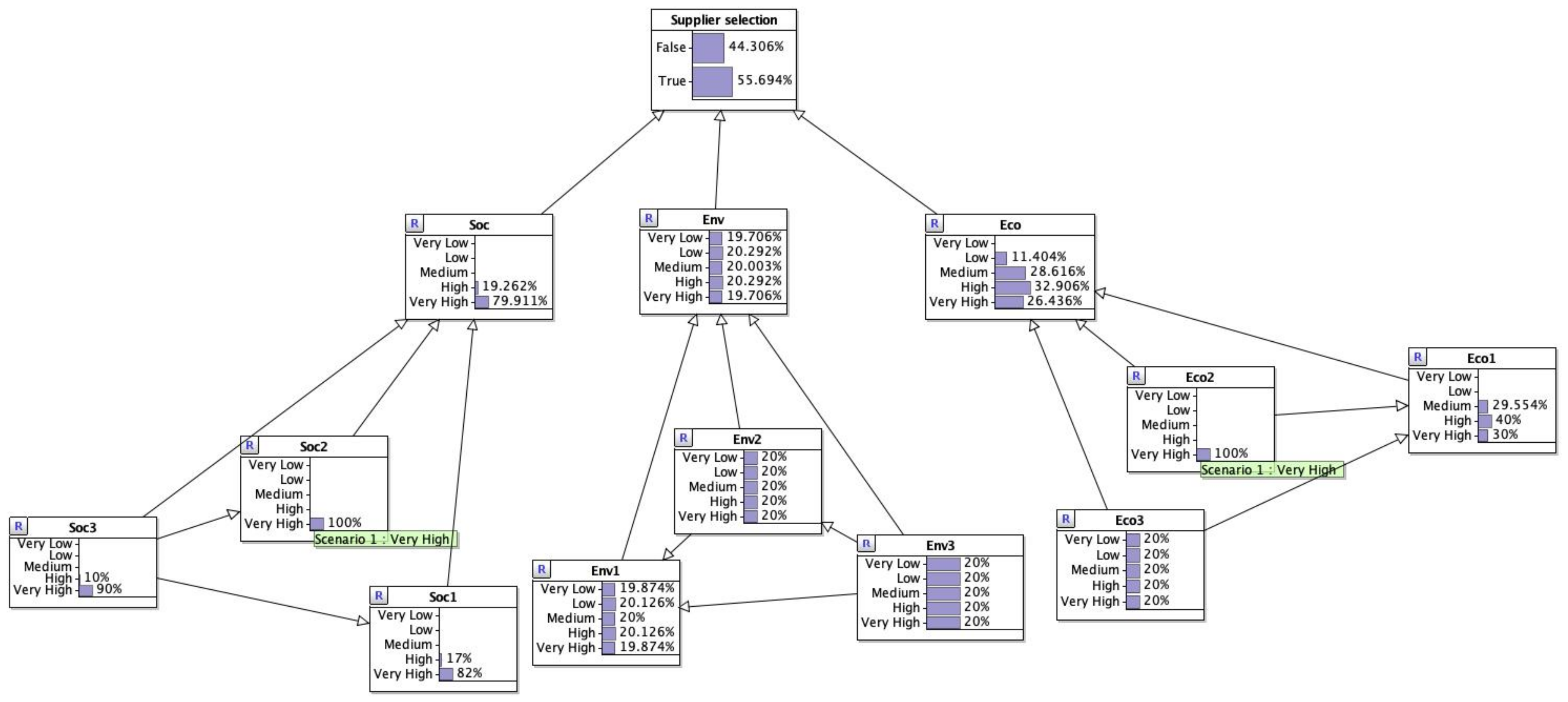

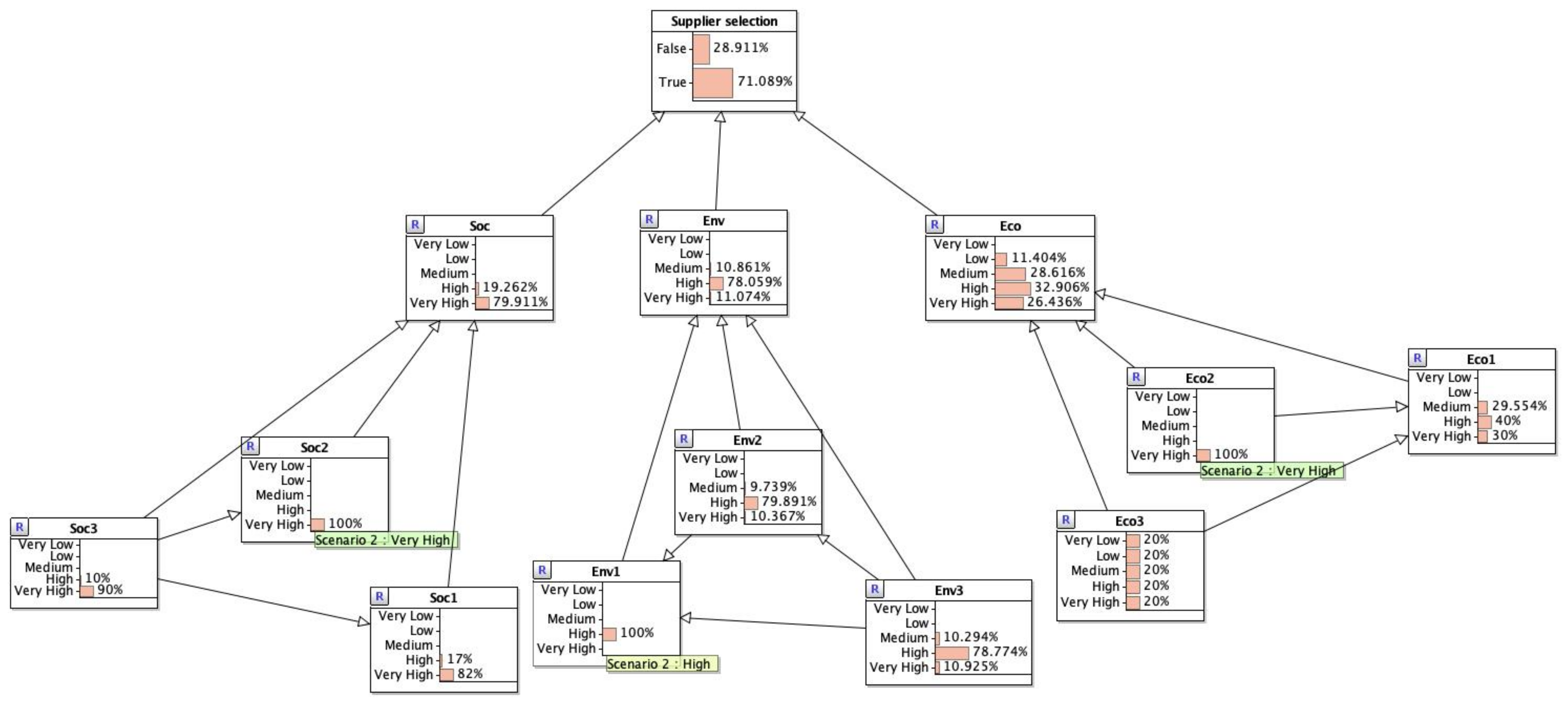

3.3. Defining the States and Parametrizing the Bayesian Network Model

- Qualitative variables have ranked responses with five ordinal states including very low, low, medium, high and very high for dimensions and criteria levels. These variables are represented by a ranked nodes method that reduces the number of parameters needed for each variable and simplifies the definition of NPTs for decision-makers. Ranked nodes assume a truncated normal (TNormal) distribution with a central tendency towards the probability of parent nodes due to a weighted function [24]. In this study, a weighted average (wmean) function for the ranked nodes is used. This function requires a coefficient and a variance parameter for every parent variable. These parameters are defined using AHP results for sustainable dimension nodes. The DEMATEL results are used for the criteria nodes.

- Boolean variables have binary responses with true or false states. These variables are represented in the supplier selection node. For example, if (parents > 0.6, “True”, “False”), meaning “if the sum of the parent values is greater than 0.6 then the value is ‘True’; otherwise, it is ‘False’”.

3.4. Completing a Sensitivity Analysis

3.5. Applying the Proposed Bayesian Network Model

4. Results Analysis and Managerial Implications

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings and Contributions

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Future Research Directions

- This study was more methodologically oriented as the research showed how the methodology can integrate various complex issues in managerial decision-making. As the problem size increases, the applicability and accuracy of the model will require further investigation. For example, what if the number of factors increases regarding the number of alternatives or criteria?

- A complete validation of the study will be undertaken by considering more scenarios. Experimenting with the methodology would be worthwhile to determine if all scenarios are supportive. For example, what if all the data were known, or only known data were utilized? What if none of the data were known and it was a completely new product with new suppliers? How well can the model learn? These are all questions that may be asked in various experimental scenarios or in long-term longitudinal studies.

- It will be also useful to expand the BN model with indicators for some criteria and to consider the decision-maker characteristics; for example, would supply chain managers differ from engineering or marketing managers?

- Furthermore, the proposed model can be solved by using other approaches and the obtained results can be compared with each other using the Spearman rank correlation method, such as multiple criteria tools including ANP, TOPSIS and PROMETHEE, to name a few. Otherwise, different methods can be compared regarding the time, the complexity and the restriction on the number of alternatives or criteria used in the selection process in order to identify which method is more robust.

- Additionally, this study can be extended to other domains for evaluation and selection decision-making problems. The update of the evaluation criteria according to each specific case will be necessary.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rostamzadeh, R.; Ghorabaee, M.K.; Govindan, K.; Esmaeili, A.; Nobar, H.B.K. Evaluation of sustainable supply chain risk management using an integrated fuzzy TOPSIS- CRITIC approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Ahmadi, H.B.; Sarkis, J. Social sustainable supplier evaluation and selection: A group decision-support approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7046–7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Liu, J.N.K.; Ngai, E.W.T. Application of decision-making techniques in supplier selection: A systematic review of literature. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 3872–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Chandra, C. An integrated buyer initiated decision-making process for green supplier selection. J. Manuf. Syst. 2016, 41, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, K.; Fröhling, M.; Schultmann, F. Sustainable supplier management—A review of models supporting sustainable supplier selection, monitoring and development. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 1412–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konys, A. Green Supplier Selection Criteria: From a Literature Review to a Comprehensive Knowledge Base. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P.; Paul, S.K. Applications of MCDM methods in research on corporate sustainability: A systematic literature review. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 31, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Xiao, J. A Novel Decision-Making Framework for Sustainable Supplier Selection Considering Interaction among Criteria with Heterogeneous Information. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Dhavale, D.G. Supplier selection for sustainable operations: A triple-bottom-line approach using a Bayesian framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 166, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Rajendran, S.; Sarkis, J.; Murugesan, P. Multi criteria decision making approaches for green supplier evaluation and selection: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 98, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweiri, F.; Kumar, S.; Khan, S.A.; Jain, V. Designing an integrated AHP based decision support system for supplier selection in automotive industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 62, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Kumar, D.T.; Shankar, K.M.; Kannan, D.; Chen, G. Analyzing criteria and sub-criteria for the corporate social responsibility-based supplier selection process using AHP. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 68, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.; Govindan, K.; Gold, S. Multi-tier sustainable global supplier selection using a fuzzy AHP-VIKOR based approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 195, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Fang, Z.; Shah, S.A.A.; Akbar, M.A.; Alsanad, A.; Gumaei, A.; Solangi, Y.A. A Hybrid Multi-Criteria Approach for Evaluation and Selection of Sustainable Suppliers in the Avionics Industry of Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafa, N.; Hani, Y.; El Mhamedi, A. Evaluating and selecting partners in sustainable supply chain network: A comparative analysis of combined fuzzy multi-criteria approaches. Opsearch 2018, 55, 14–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalalah, D.; Hayajneh, M.; Batieha, F. A fuzzy multi-criteria decision making model for supplier selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 8384–8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Chang, C.-W.; Wu, C.-H. Fuzzy DEMATEL method for developing supplier selection criteria. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 1850–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.; Hsu, C.-W.; Li, J.-Y. Developing a green supplier selection model by using the DANP with VIKOR. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1661–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Kumar, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Industry 4.0 as an enabler of sustainability diffusion in supply chain: An analysis of influential strength of drivers in an emerging economy. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1505–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.; Borenstein, D. A fuzzy-Bayesian model for supplier selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 7834–7844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, N.; Neil, M. Risk Assessment and Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan, I.; Aydin, N. Combining Bayesian Networks and Total Cost of Ownership method for supplier selection analysis. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2011, 61, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Z.U.; Ali, H.M.K.; Hussain, S.; Wasim, A.; Jahanzaib, M. Supplier selection in an industry of short lifecycle products using bayesian network analysis. Pak. J. Sci. 2016, 68, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, R.; Yet, B. Building Bayesian Networks based on DEMA℡ for Multiple Criteria Decision Problems: A Supplier Selection Case Study. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 134, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Barker, K. A Bayesian network model for resilience-based supplier selection. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 180, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.; Shankar, R.; Yadav, S.S.; Thakur, L.S. Supplier selection using fuzzy AHP and fuzzy multi-objective linear programming for developing low carbon supply chain. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 8182–8192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Xu, G.; Dong, J. Supplier selection using ANP and ELECTRE II in interval 2-tuple linguistic environment. Inf. Sci. 2017, 385–386, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Govindan, K.; Kannan, D.; Mangla, S.K.; Garg, C.P. An integrated framework for sustainable supplier selection and evaluation in supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1686–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Pamucar, D.; Zavadskas, E.K. Evaluating the performance of suppliers based on using the R’AMATEL-MAIRCA method for green supply chain implementation in electronics industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Jiang, S.; Song, W.; Ming, X. A Rough Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Approach for Sustainable Supplier Selection under Vague Environment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Zarate, P.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E.; Turskis, Z. A combined compromise solution (CoCoSo) method for multi-criteria decision-making problems. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 2501–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Jiang, D.; Ullah, A.M.M.S.; Noor-E-Alam, M. Resilient supplier selection in logistics 4.0 with heterogeneous information. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 139, 112799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahriri, F.; Osman, M.R.; Ali, A.; Yusuff, R.M.; Esfandiary, A. AHP approach for supplier evaluation and selection in a steel manufacturing company. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2008, 1, 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabus, A.; Fontela, E. World Problems, an Invitation to Further Thought within the Framework of DEMATEL; Battelle Geneva Research Center: Geneva, Switzerland, 1972; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, T.; Pearl, J. Causal networks: Semantics and expressiveness. In Machine Intelligence and Pattern Recognition; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; Volume 9, pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Eckert, C.; Yannou-Le Bris, G.; Petit, G. A fuzzy decision tool to evaluate the sustainable performance of suppliers in an agrifood value chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 127, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J.D. Models and managers: The concept of a decision calculus. Manag. Sci. 1970, 16, B-466–B-577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Henderson, J.C. An Evolutionary Strategy for Implementing a Decision Support System. Manag. Sci. 1981, 27, 1309–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Year | Decision Criteria | Methods | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco. | Env. | Soc. | |||

| [22] | 2011 | x | BN, Total cost of ownership | ||

| [16] | 2011 | x | DEMATEL, TOPSIS | ||

| [17] | 2011 | x | Fuzzy DEMATEL | ||

| [20] | 2012 | x | BN fuzzy logic | ||

| [26] | 2012 | x | x | Fuzzy AHP, fuzzy LP | |

| [12] | 2013 | x | x | x | AHP |

| [18] | 2015 | x | x | DEMATEL, VIKOR | |

| [9] | 2015 | x | x | x | BN, Markov chain |

| [23] | 2016 | x | BN | ||

| [11] | 2016 | x | AHP | ||

| [25] | 2016 | x | x | BN | |

| [27] | 2017 | x | Interval 2-tuple, ANP, ELECTRE | ||

| [28] | 2017 | x | x | x | AHP, VIKOR |

| [29] | 2018 | x | x | DEMATEL, ANP, MAIRCA | |

| [13] | 2018 | x | x | x | Fuzzy AHP, VIKOR |

| [15] | 2018 | x | x | x | AHP, PROMETHEE, TOPSIS |

| [30] | 2018 | x | x | x | ELECTRE |

| [2] | 2019 | x | BWM, TODIM | ||

| [31] | 2019 | x | CoCoSo | ||

| [24] | 2019 | x | BN, DEMATEL | ||

| [32] | 2020 | x | TOPSIS | ||

| [14] | 2020 | x | Fuzzy AHP, fuzzy TOPSIS | ||

| This study | x | x | x | AHP, DEMATEL, BN | |

| Economic Criteria (ECO) | Environmental Criteria (ENV) | Social Criteria (SOC) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco1 | Eco2 | Eco3 | Env1 | Env2 | Env3 | Soc1 | Soc2 | Soc3 |

| 1 | 1/3 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1/5 | 1/3 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 1/5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| 1/5 | 1/3 | 1 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1 | 3 | 1/5 | 1 |

| Dimensions Weights | Criteria | Total Weights | Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECO (0.618) | Eco₁ | 0.350 | CR = 0.090 |

| Eco₂ | 0.067 | ||

| Eco₃ | 0.199 | ||

| ENV (0.297) | Env₁ | 0.193 | CR = 0.086 |

| Env₂ | 0.038 | ||

| Env₃ | 0.066 | ||

| SOC (0.086) | Soc₁ | 0.008 | CR = 0.078 |

| Soc₂ | 0.017 | ||

| Soc₃ | 0.060 |

| Eco1 | Eco2 | Eco3 | q | p | q + p | q − p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco1 | 0.143 | 0.114 | 0.171 | 0.484 | 1.286 | 1.714 | −0.857 |

| Eco2 | 0.571 | 0.057 | 0.085 | 0.714 | 0.228 | 0.943 | 0.486 |

| Eco3 | 0.571 | 0.057 | 0.086 | 0.714 | 0.343 | 1.057 | 0.371 |

| Env1 | Env2 | Env3 | q | p | q + p | q − p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Env1 | 0.303 | 0.376 | 0.254 | 0.932 | 1.971 | 2.904 | −1.038 |

| Env2 | 0.696 | 0.226 | 0.182 | 1.104 | 1.441 | 2.545 | −0.337 |

| Env3 | 0.972 | 0.839 | 0.215 | 2.026 | 0.651 | 2.677 | 1.375 |

| Soc1 | Soc2 | Soc3 | q | p | q + p | q − p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soc1 | 0.053 | 0.114 | 0.111 | 0.278 | 0.659 | 0.937 | −0.381 |

| Soc 2 | 0.098 | 0.068 | 0.111 | 0.278 | 0.841 | 1.119 | −0.563 |

| Soc 3 | 0.508 | 0.659 | 0.111 | 1.278 | 0.333 | 1.611 | 0.944 |

| State | Eco1 (Cost) | Eco2 (Scrap Rate) | Eco3 (Delivery on Time) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | >200$ | >10% | 97% |

| Low | (150$, 200$) | (5%, 10%) | (97%, 98%) |

| Medium | (100$, 150$) | (2%, 5%) | 0,98% |

| High | (50$, 100$) | (1%, 2%) | (98%, 99%) |

| Very high | Price < 50$ | <1% | >99% |

| State | Env1 (Total Emitted kgCO2e/kg Product) | Env2 (Energy Performance Indicator in kwh/m2/year) | Env3 (Environmental Certification ISO 14001) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | >750 | >160 | Supplier has no environmental certification |

| Low | (500, 750) | (130, 160) | Supplier has green practices |

| Medium | (250, 500) | (100, 130) | Supplier is in level 1 of ISO 14001 |

| High | (25, 250) | (70, 100) | Supplier is in level 2 of ISO 14001 |

| Very high | <25 | <70 | Supplier is in level 3 of ISO 14001 |

| State | Soc1 (Temporary Workers) | Soc2 (Number of Incidents Per Year Per 1000 Employees) | Soc3 (Responsibility Budget as Percent of Sales) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | >60 | >100 | <0% |

| Low | (50, 60) | (80, 100) | (1%, 2%) |

| Medium | (35, 50) | (60, 80) | (2%, 5%) |

| High | (20, 35) | (40, 60) | (5%, 10%) |

| Very high | <20 | <40 | >10% |

| Parameters | How Much Does Cost (Eco1) Influence the Economic Dimension (Eco)? | How Much Does Quality of Product (Eco2) Influence the Economic Dimension (Eco)? | How Much Does Quality of Service (Eco3) Influence the Economic Dimension (Eco)? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.350 | 0.067 | 0.199 |

| Variance | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Parameters | How Much Does (Eco2) Influence (Eco1)? | How Much Does (Eco3) Influence Cost (Eco1)? |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 3.33 | 3.33 |

| Variance | 0.333 | 0.333 |

| Criteria | S1 | S2 | S3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eco1 | High | Medium | Medium |

| Eco2 | High | High | High |

| Eco3 | High | High | Very high |

| Env1 | No information | High | No information |

| Env2 | Medium | No information | No information |

| Env3 | High | No information | High |

| Soc1 | High | High | No information |

| Soc2 | Low | Medium | No information |

| Soc3 | Medium | Medium | High |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kafa, N.; Jaegler, A.; Sarkis, J. Harnessing Corporate Sustainability Decision-Making Complexity: A Field Study of Complementary Approaches. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410584

Kafa N, Jaegler A, Sarkis J. Harnessing Corporate Sustainability Decision-Making Complexity: A Field Study of Complementary Approaches. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410584

Chicago/Turabian StyleKafa, Nadine, Anicia Jaegler, and Joseph Sarkis. 2020. "Harnessing Corporate Sustainability Decision-Making Complexity: A Field Study of Complementary Approaches" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410584

APA StyleKafa, N., Jaegler, A., & Sarkis, J. (2020). Harnessing Corporate Sustainability Decision-Making Complexity: A Field Study of Complementary Approaches. Sustainability, 12(24), 10584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410584