Abstract

The sharing economy (SE) has drawn significant attention from several society stakeholders in the last five years. While business actors are interested in financial opportunities to meet consumer needs, new business models, academia and governmental organisations are concerned with potential unintended effects on society and the environment. Despite its notable global growth, there is still a lack of more solid ground in understanding its origins and respective mechanisms through which it has been evolving as a category. This research addresses the problematics of the origins and ascendency of the SE by examining the process by which it is arising as a new category, searching for conceptual clarification, and pinpointing the legitimacy granted by stakeholders. Our guiding research questions are: how the SE was formed and evolved as a category, and as a category, is the SE legitimate? Additionally, we attempt to identify the nature of the SE as a category. Making a historical analysis of the expression SE and its equivalents, this paper deepens the discussion about the SE’s nature by providing evidence that it has predominantly been formed by emergence processes, comprising social movement, similarity clustering, and truce components, which render the SE a particular case of category formation and allow communication, entrepreneurship, regulation, and research about what it is. Moreover, the findings reveal a generalised legitimacy granted to the SE by a vast number of stakeholders, although still lacking the consolidation of socio-political legitimation. The SE’s nature seems to fall into a metaphorical approach, notably, the notion of radial categories.

1. Introduction

The sharing economy (SE) is growing at an impressive rate across the globe [1]. It involves using information technologies to link different stakeholders to use surplus resources to create valuable products and services. As a new phenomenon, there is a lack of shared understanding of the nature of the SE and its underlying mechanisms [2], as well as empirical research into the increasing diversity of SE business models and the implications for business growth, community development, sustainability and public policy [3].

Despite increased awareness of the SE, its nature and establishment as a legitimate category are not well understood. Some companies are often classified as SE exemplars, and at the same time, lack the required legitimacy to operate in specific markets. Uber is one such case. In Korea [4], for example, taxi unions objected strongly to Uber, and as a consequence, the Korean government banned many of the company’s services. Several European countries, namely France, Germany, Spain, and the UK, saw prominent protests by taxi driver associations against the company, giving rise to concerns that government regulators may favour those associations over Uber. In this respect, the Court of Justice of the European Union has recently emphasised the need to resolve this issue:

“The Court finds that we must regard that intermediation service as forming an integral part of an overall service whose main component is a transport service and, accordingly, must be classified not as an ‘information society service’ but as a ‘service in the field of transport’” [5].

The Court’s explicit use of the expression “must be classified,” reveals how vital categories are. Clarifying how one should label and categorise the company has profound consequences on Uber’s operation and its substitutes (taxis). In this case, the two competing categories are an information society service versus a transport service. Being classified in one of these categories—information society or transport—makes a decisive difference. In the same vein, the Portuguese Federation of Taxis also considers it urgent to find the right “label” for Uber to identify it as belonging to a correct category: “Today, Uber has written on its forehead: a company of transportation” [6]. Oddly, during all this controversy, and to the best of our knowledge, Uber has never presented itself as an SE company, but rather as a platform. It is an exciting way to use membership to a category in a purely strategic way and not as self-definition, as it predicts the social actor’s view of organisational identity [7]. The SE seems to be a label used by some actors but not others, and it is not clear how this category was formed and by whom.

In this research, we shed light on the SE’s categorisation mechanisms, showing how different audiences provide legitimacy to the SE as a category over time. In doing so, we address the calls by Cheng [8] and Parente et al. [9] to set up a relevant future research agenda and broaden current theories by exploring why, when and how SE commercial platforms expand into societies. We also address the call by Cohen and Kietzmann [1] regarding the urgency in studying the phenomenon and Knote and Blohm’s [2] concern about finding a common understanding of the SE and its underlying mechanisms. In this paper, we analyse how the meaning of the SE evolved. We examine the process by which the SE is arising as a new category, searching for conceptual clarification and pinpointing the legitimacy granted by critical stakeholders. Thus, our guiding research questions are (RQ1) how the SE was formed and evolved as a category; (RQ2) as a category, is the SE legitimate? Additionally, we attempt to identify the nature of the SE as a category.

By interpreting keywords, concepts, and patterns of discourse used by a range of stakeholders in construing the dimensions associated with the formation of the category of SE and its evolution through time, we constructed a timeline that ranges from 2002 to 2019, comprising three main phases—“revelation phase,” “clairvoyance phase” and “knowledge proliferation phase,” each one containing distinct formation processes and different actors playing prominent roles. The SE has been formed mainly by emergence processes [10] in which social activists, through a process of social movement [11], have claimed its value as a means to achieving a more sustainable world, which was followed by the process of similarity clustering [11] significantly benchmarked by an appropriation of the field by the scientific community, striving to give sense to and clarify the nature of this emergent phenomenon, which allowed the achievement of a truce momentum [12], thus allowing communication, entrepreneurship, regulation, and research into what the SE is, despite the evident lack of agreement regarding both the label and its content. Complementarily, we suggest that the SE is a category that is closer to a radial category [13,14] than to a more conventional prototype category [15,16,17]. In our view, it is the combination of all the processes mentioned above that renders the SE a particular case of category formation.

This article is organised as follows. We begin by presenting a theoretical framework, including a brief review of the idea of the SE, explaining what categories are and how new categories are formed and legitimacy construed. After describing the data collection processes, we present a historical analysis of how the category of SE has been formed and evolved, highlighting each of the milestone events and shedding light on critical dimensions associated with forming a legitimate category. After that, we discuss the study’s limitations and avenues for further research. Finally, the conclusion section provides a summary of the main findings.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Conceptualising the SE

Sharing is as old as humankind. People often have shared assets. The SE, however, is a relatively new phenomenon by way of technology standards [18], born of the Internet age [19], and in which you are not helping a friend for free or with the expectation of reciprocity, but instead providing SE services to a stranger for money [14]. Sharing and collaborative consumption are growing in popularity today. The growth of these practices generates a debate around the implications for businesses still using traditional models of sales and ownership [19]. Although in 2004, Benkler [20] had already introduced a discussion about a new emergent economic practice, a modality of economic production which he called “sharing,” it is believed that the term Sharing Economy itself has been used since 2007, when a law professor named Lawrence Lessig at Harvard Law School used the term in a New York Times story about the Internet’s effect on work, followed by publication in 2008 of a book called Remix: Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. He explained:

“The traditional company is just making money selling widgets or iTunes. The Internet exploded a sharing economy with things like Wikipedia, where people are doing work that creates a lot of value, not for money but just because it’s their hobby. We’ve seen a pattern of hybrid companies like this trying to figure out ways to leverage that for a profit” [21].

These hybrid companies referred to by Lessig may also be perceived as what Cohen and Kietzmann [1] call commercial sharing services that allow people to share resources in creative new ways. Malhotra and Van Alstyne [22] say that thanks to these SE sharing services, people can have access to rooms—Airbnb, Roomorama—cars and bicycles—Relay Rides, Wheelz—and taxi services—Uber, Lyft. These creative business models have spotlighted the SE and its massive growth in sources ranging from Fortune Magazine to President Barack Obama [23]. Further, the SE was nominated as one of ’10 ideas that will change the world’ [24], and its value was estimated at $26 billion in 2013 [25,26], being projected to grow to $335 billion in 2025 [27].

Attempts to label this emergent phenomenon have appeared. In a report issued in June 2016, the Economics and Statistics Administration (ESA) of the US Commerce Department attempted to define and map out the contours of this emerging business sector, labelling its participants as digital matching firms. The report describes this sector through four main characteristics [28]: (a) they use information technology (IT systems), typically available via web-based platforms, such as mobile “apps” on Internet-enabled devices, to facilitate peer-to-peer transactions; (b) they rely on user-based rating systems for quality control, ensuring a level of trust between consumers and service providers who have not previously met; (c) they offer the workers who provide services via digital matching platforms flexibility in deciding their typical working hours; (d) to the extent that tools and assets are necessary to provide a service, digital matching firms rely on the workers using their own.

But the term SE itself raised significant concerns. A PwC report [29] on assessing the SE used the label broadly to define the emergent ecosystem that is upending mature business models worldwide. The report has concluded that no single label can neatly encapsulate this movement, after having spoken to industry specialists, as for some, the word “sharing” was a misnomer, a savvy-but-disingenuous spin on an industry they felt was more about economic opportunism than altruism. We believe that this duality, involving the selfish exploitation of an opportunity and some sort of contribution to others’ welfare, goals that usually do not go together, is a crucial cornerstone in grasping the nature of this movement.

There is much ambiguity surrounding the SE. For example, these new related business and consumption practices have been described as sharing [30], collaborative consumption [31], the mesh [32], commercial sharing systems [33], co-production [34], co-creation [35,36], prosumption [37,38], product-service systems [39], access-based consumption [40], consumer participation [41], and online volunteering [42].

Others argue that the SE seems to be paradoxical [43]. Tensions and uncertainties regarding its real boundaries, effects and logics highlight the SE [44], where some perceive it as an alternative to market capitalism, but at the same time, it might instigate capitalism [45]. Even if it defends and promotes “more sustainable consumption and production practices,” it might also “reinforce the current unsustainable economic paradigm” [46] (p. 159).

The paradoxical features associated with the SE converge on the dual nature of this emergent process. However, this ambiguous context does not inhibit further efforts to construe more solid common ground in broaching the SE. For example, Frenken and Schor [47] (pp. 4–5) have defined the SE as a phenomenon where “consumers grant each other temporary access to under-utilised physical assets (‘idle capacity’), possibly for money,” where prototypical “goods that are currently shared are cars and homes.” Further, SE platforms should be defined in alliance with the notion of sharing as a historical practice, in the sense that people were already involved in practices of lending, renting and, particularly, sharing goods with well trusted social contacts, long before the emergence of Internet platforms [47]. On that premise, Frenken and Schor [47] argue that what is new today is that people lend goods to others they do not know due to the simple fact that the Internet allows an enormous decrease in transaction costs. Today, because of Internet platforms, we can lower the costs of the search and contract. Based on this definition, the authors advocate that the SE is different from three other types of platforms pre-dating the Internet: (1) second-hand economy (consumers selling goods to each other); (2) product-service economy (renting goods from a company rather than from another consumer); and (3) on-demand economy (peer-to-peer service delivery instead of fair peer-to-peer sharing).

Given the complexity and uncertainties associated with the SE, representing the absence of shared understanding about both the label and the SE content, we find further attempts to construe more consistent building blocks regarding what the SE is and what its constituent activities are. This follows below.

2.2. SE as a Complex Category: Organising the Diversity under an Ambiguous Umbrella

In the face of various new businesses likely to be categorised as SE, some researchers have developed typologies anchored in very different dimensions [48,49,50]. The duality between maximization of individual benefits and a collective orientation seems to be one of the primary sources of discussion, divergence and unsettled discourse among the academic community. In an attempt to organise the wide range of non-ownership forms of consumption practices, Habibi et al. [50] suggest the sharing-exchange continuum as a fundamental dimension against which all those forms can be mapped, thus, helping to distinguish the degree to which actual sharing (from “pure sharing” to “pure exchange”) is being offered by an SE practice (called an SBP—Sharing-Based Program). The continuum uses a rating given to an SBP in measuring its sharing scores (on a 5-point scale), which is based on several sharing and exchange-related characteristics drawn from Belk’s work [30,51]. Habibi et al.’s [52] results reveal that (1) Zipcar SBP was rated as being at the “pure exchange” end of the continuum, (2) Couchsurfing SBP was rated as being at the “pure sharing” end of the continuum, and (3) Airbnb SBP was rated as being a “hybrid” practice, having a mix of “pure exchange” and “pure sharing” characteristics, thus situated in the middle of the continuum.

Other authors have attempted to organise the diversity of business forms using more than one dimension. For instance, Schor [48] proposes market orientation (for-profit vs non-profit) and market structure (peer-to-peer vs business-to-peer) as useful measurements to highlight differences and similarities between SE elements. In Schor’s account, these dimensions shape the activities’ business models, logics of exchange, and potential to disrupt conventional businesses. The author pinpoints SE activities according to the shared sameness with other category members and the individual distinctiveness from other members. Although the for-profit or non-profit orientation seems to mirror the sharing-exchange fundamental motivation of the service provider, as suggested by Habibi et al. [50], thus highlighting the essential duality of self-interest versus others’ interest that seems to cross the discussion of the nature of the SE, Schor’s [48] typology also includes the level of formalisation of one of the elements of the exchange relationship: is a business involved or not? This is relevant because, typically, business type stakeholders tend to be exclusively concerned with making profits, thus stressing the duality’s interest. Thus, Schor’s typology can also be mapped on just one dimension.

As an attempt to give meaning to SE, other dimensions have been added. For instance, Constantiou et al. [49] suggest combining the level of control applied by the platform owner over platform participants (loose vs. tight) and the magnitude of rivalry among the platform participants adopted by the platform owner (low vs high). In this approach, what differentiates SE platforms from more traditional marketplaces, supplier networks, third-party intermediaries, and service integrators is how they combine organisational and market mechanisms to coordinate platform participation and engender value. According to Constantiou et al. [49], there are four distinct combinations (or models), which they call Franchiser, Principal, Chaperone and Gardener, according to the variety of the control and rivalry dimensions: control is governed by extending organisational coordination mechanisms into the platform’s user base, whereas rivalry is governed by the market coordination mechanism designed by the platform owner.

In short, scholars have used variety in understanding the nature of the SE. Some attempts have been made to categorise the field, thus recognising intra-category diversity, and SE has been perceived as an umbrella concept. Different dimensions have been used to describe the field, but the self-others interest seems to be the most relevant. Finally, most authors do not question the legitimacy of specific business models, except for Uber, which leads to terminological ambiguity surrounding the SE [53]. In our view, this happens because, even though some studies (e.g., [54]) already draw special attention to the dynamics of the SE in terms of how resource-sharing markets emerge and change, and the intended and unintended consequences of resource sharing, there is a lack of research analyzing its actual roots, highlighting where it comes from and how its conceptualisation has been evolving.

Interestingly, this lack of consensus in defining the SE, with disagreement as to both the label and the content of the category, did not prevent the growth of the SE, both as a dynamic economic activity and as a subject of study for a growing number of researchers. We join this discussion by exploring how categories are formed and evolve. We believe this article can shed light on SE dynamics and can be another step in reducing the ambiguity associated with the SE. Reducing diversity and ambiguity is precisely the primary function of categories, both at the individual and collective levels. To assess whether the SE is a legitimate new category, it is essential first to understand how new categories emerge, and legitimacy is construed. This follows below.

2.3. How New Categories Emerge, and Legitimacy Is Construed

2.3.1. Categories

Categories are essential for daily human functioning. They help humans deal with the great diversity of objects, events and ideas surrounding them, thus performing basic sense-making and communication functions. It is almost impossible to perceive, think or talk without resorting to some kind of category [13]. Additionally, shared categories enable effective communication. Categorisation happens automatically and unconsciously. Every time we wake up, we organise our physical world into categories, including people, animals and material objects. But we also categorise almost our entire abstract world, regarding events, emotions, social relationships, governments or theories [13]. Curiously, the first thing people want to know about us before we are born is the classic categorical question heard by pregnant women: is it a boy or a girl? In ordering a beer, knowing whether it is artisanal or made by a large producer can be decisive for some consumers.

At the individual level, the function of categories is to reduce uncertainty and allow thinking to interact in a reasonably cognitive productive manner. The economic sphere is no exception to this human tendency to minimise variability and increase predictability: countries classify their enterprises based on comprehensive sets of categories that describe their core activities. Other more complex categories concern different types of activity and place organisations in the public, private or non-profit sectors, in relation to the type of ownership and purpose. In its most basic sense, the meaning of categorisation is simple: members of a category are similar to each other and different from members of another category. Based on this sense of belonging, the members of a category can define themselves according to what unites them and what differentiates them. As categories are eminently social, external elements can look at an entity as a member of a category, and based on this, form expectations about the actions of that entity, without the need for a great deal of individualised information processing.

Metaphorically, categories are conceptualised as containers of similar objects separating those that are in from those that are out [13]. This is also the dominant perspective of categories shared by laypeople. But this view was challenged by at least two perspectives, namely the prototype approach [15] and the metaphorical approach [13]. These two alternative views of categories posit that members of categories do not need to share their properties as belonging to that category. Those category boundaries are not necessarily definite, thus threatening the very meaning of what a category is.

Following a wide range of experiments, the prototype view of categories [16,17] established that subjects perceive some subcategory or category members as more representative than others, becoming more prototypical members. For example, a robin is a more prototypical member of the bird category than a chicken. Members of a category can be rated as more or less prototypical. Thus, categories have a prototypical structure, and these prototypes play an essential role in making inferences about category members, thus acting as cognitive reference points. Reference points are especially relevant in categories without rigid boundaries, like SUV as a vehicle category, in which prototype effects result from the degree of category membership.

Like the prototypical view, the metaphoric approach to categories [13] suggests that categories are not homogeneous sets of elements, but it proposes different structural properties in some categories, named radial categories. Using a combination of a container and centre-periphery metaphors, according to which humans view concepts as containers of something (meaning) and everything necessary is perceived as being located in the centre [14], this approach describes radial categories as including central subcategories and non-central subcategories whose characteristics cannot be inferred from the prominent members. Non-central members of the category belong to the category because conventions render them variations of the principal members and must be learned with a specific culture. Non-central subcategories are not created from the central ones following general rules and are seen as variations of the central subcategories, extended according to conventions. The central subcategory determines the possibilities for extension and establishes the relationships between a prominent model and the others [13]. Thus, radial categories are characterised by a conventionalised centre, with several usually metaphoric extension principles describing what links central and less central categories, and specific conventional extensions that cannot be predicted from the centre and have to be understood and learned as separate independent elements [13]. For example, in the mother category, the primary subcategory is defined by the convergence of the cognitive models of birth, nurture, etc.

In contrast, non-central extensions are all possible variations of the mother condition—adoptive mother, birth mother, foster mother, surrogate mother, etc. In other words, the non-central extensions are understood via their relationship to the central model. Radial categories are essential not only because they equip us with the vocabulary required for characterising relationships between subcategories, but also because they do not prescribe limits for inclusion, which permit the category’s extension. In this sense, radial categories give us a more flexible cognitive tool to accommodate novelty, a property not theorised within the prototype perspective.

A more flexible approach to categories can stress that, beyond prototypical gradients, categories can be formed based on the existence of similar goals or the presence of an identical causal relationship in actors [55]. In markets, belonging to categories is vital to organisations’ strategic and symbolic action, as categories provide essential labels for an organisation to stand out in its field [56]. For example, when creating a new organisation, entrepreneurs can use the new venture’s membership of an established category to gain immediate legitimacy from external audiences through rituals of compliance with regulators. This organisation can counterbalance this pressure for isomorphism by strategically developing a differentiated value proposition that captures customers, suppliers or investors [56]. But how are categories born and formed? This follows below.

2.3.2. The Formation of Categories

When used as lenses to look at markets and organisations, “categories provide a cognitive infrastructure that enables evaluations of organisations and their products, drives expectations, and leads to material and symbolic exchanges” [55] (p. 1102). Categories are, thus, fundamental cognitive devices required for actors to navigate in complex environments like markets. In line with other domains, categories include entities grouped under a label. The formation of these features is mostly socially constructed by relevant actors in a specific field or ecosystem.

As Hannan et al. [57] (p. 47) point out, the process of assigning explicit labels or names to sets of entities means that it “crystallise (s) the sense that (individuals) have identified commonality”. In the same vein, Galperin and Sorenson [58] suggest that a label representing a category tends to emphasise similarities between entities, facilitates communication about the whole of entities, and smoothes the cognitive process of storing and transferring information about the attributes of specific category members. Thus, studying the emergence of a label, and evolution of the meaning attached to it, can inform us about the origins and change of a category. In this regard, a fundamental question arises: how are categories formed?

In recent years, scholars have addressed questions about the origins of categories and how new ones emerge [56,59,60,61]. In a recent review, Durand and Khaire [10] suggest that the formation of a category, which demands the rearrangement, reinterpretation and reassessment of existing elements and features, is a process that defies the status ordering of actors in an ecosystem. In describing category formation, the authors propose a clear distinction in the category formation process, distinguishing category emergence from category creation. Emergence occurs when it “crosses over categorical systems and hierarchies and results in the existence of new actors and organisational forms” [10] (p. 89), whereas creation “contributes to the rejuvenation of existing category systems but preserves the social structuration of markets” [10] (p. 89). According to Durand and Khaire [10], seven critical dimensions allow assessment of whether we are in the presence of one or the other: nature of the novelty, origin, organisational agency, mechanism for distinction, the basis of discourse, legitimacy through which it is acquired, and outcome. According to this framework, category emergence happens when the category’s formation arises from elements extraneous to an existing market. Complementarily, category creation occurs when there is a redesigning of cognitive boundaries around a subset of features within a pre-existing category system [10].

Emergence and creation are not the only processes explaining how categories are formed. In assessing the literature to explain the emergence of the Tex-Mex food category, Wheaton and Carroll [11] noted the existence of two theoretical streams explaining how categories emerge, namely the social-movement and the similarity-clustering approaches. The social movement highlights the role of activists who attempt to articulate a “theory” of the nascent category and persuade others about its value. Often, very well identified activists tend to use the label as much as possible and attempt to present a compelling and positive story about the label to influence the audience’s acceptance of the category. Rao et al.’s [62] explanation of the emergence of nouvelle cuisine is an example of this perspective.

The similarity-clustering approach shares with the social-movement perspective the key role of activists. Instead of promoting the nascent category, these actors are portrayed as aiming to cluster entities, most organisations, according to similar characteristics [11]. Different enthusiasts engage in similarity judgments in the early stages of category formation. Still, they do not achieve consensus [57], and the process of comparison between new entities and between those and existing ones continue until individuals reach consistent groupings of entities and a label is assigned. Unlike the social-movement perspective, these individuals are genuinely interested in the meaning of the category and are not necessarily motivated to sell the label and others’ content. After this refined labelling process of clusters, including similar entities, actors usually develop more general frameworks that allow observers to decide if an entity can be included in a particular group and receive the label. The process of assigning the label entails expectations of specific entities, and when enough agreement is achieved between different stakeholders, the category is said to emerge [11].

Using a process approach, Rhee et al. [12] theorised on the existence of four types of categories’ initial formation, namely proof, consensus, fiat, and truce. These four processes result from the combination of two underlying dimensions describing the degree of agreement about the meaning of a category between different constituencies (high or low) and the level of authority granted to specific actors to establish new categories (centralised or decentralised). Categories are formed by consensus when both audiences and the constituents of an emergent category agree about the meaning of a new category, and category legitimacy does not need official endorsement from authorities. Categories are formed by proof when an established authority, or existing influential experts or actors, uses institutionalised rules to develop a new category. Other actors concur and accept its meaning. Sometimes, centralised authorities establish new categories and use their power to impose the category on actors who do not recognise or want it, a process named fiat. Finally, a category might be set up by truce, a mechanism representing the lack of agreement about the meaning of a category between relevant actors. Still, power relationships prevent the possibility of one actor imposing the importance of a category upon others, which leads to the existence of categories that are largely controversial, or at least, showing great variability in both label and content.

According to Rhee et al. [12], understanding these fundamental mechanisms explaining categories’ initial formation is essential because their prevalence affects subsequent categories’ evolution. This evolutionary perspective is relevant to understand the category formation process because, as categories evolve, both the label and the practices or features represented can change or, according to Kennedy et al. [63], be subject to redefinition, subsumption, or recombination. Some categories are more stable than others, and the critical mechanism involved in their emergence can be imprinted in subsequent category evolution.

In summary, the process of category formation is by no means straightforward. It involves multifaceted mechanisms through which newcomer entities, namely new entrepreneurial organisations or businesses, must pass. Along this process of screening and evolution, there is an element that is granted by a vast spectrum of external audiences and whose role becomes crucial in conferring meaning, appropriateness and viability to the new entities, in finding a place for them in society’s pre-established, conventions, conformities, norms or, in a nutshell, legitimacy.

2.3.3. New Categories and Entrepreneurship: The Central Role of Legitimacy

Entrepreneurial ventures require legitimacy to succeed, and categories can grant this valuable resource [64]. Even though entrepreneurs put a lot of effort into seeking success and gaining a legitimate place in the market [65], that may not be enough as there may be cases where the establishment of new market categories can flop if they do not gain legitimacy [56], cultural recognition [66] or understanding from the consumers or investors they seek to influence [67]. Legitimacy, thus, is a precondition of survival.

According to Suchman [68] (p. 574), legitimacy originates from the perception that a venture is “desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions.” Moreover, it is often achieved through isomorphism, in other words, conformity to institutionalised preferences [69], which means that entrepreneurial ventures must face established constraints [70]. However, this conformity is the opposite of entrepreneurship’s true nature, which is more associated with novelty, distinctiveness, and nonconformity [71]. Entrepreneurship legitimacy must then coexist with its contradiction and imply a sort of interchange between entrepreneurs’ emancipating aspects and the accommodation of constraints needed to acquire resources [70]. A legitimately distinctive entrepreneurial identity has paradoxical features as it embeds both conformity and deviation—circumscribing identity elements that are contradictory or oppositional [71].

The appearance of new markets, in other words, “business environments in an early stage of formation” [61] (p. 644), brings along new opportunities for entrepreneurial ventures which, despite their attraction, imply great uncertainty, as technologies, products, or processes are experimental and only partly understood [72], and product definitions are unclear or unknown [73]. The nascent category is characteristically ambiguous or ill-structured [74]. Further, this uncertainty becomes more condensed when the new market space’s entrepreneurial firms are also new [56]. Because new ventures are often incompletely formed, deficient in resources, and lacking clear or coherent identities, the achievement of legitimacy can be a particularly critical challenge for new ventures operating in new market categories [56]. Reflecting this in an SE context, the SE’s category could be an essential resource for new organisations to anchor their identity claims, especially new ventures.

The legitimation of a new category results from the interaction of actors internal to the category, i.e., the strategic and symbolic actions of entrepreneurial organisations, and actors external to the category, i.e., the interested audiences who judge its feasibility, credibility, and appropriateness [56]. Moreover, a new category exists when two or more products or services are perceived to be of the same type or close substitutes for each other in satisfying market demand. The organisations that produce or supply these related products or services are grouped as members of the same category [56]. However, although all members share the category’s collective identity, not all members are equivalent. Such collective and organisational identities lend meaning to a category. They also pose an identity challenge: member organisations need to navigate their shared sameness with other category members and their distinctiveness [56]. Resolving the dilemma of sameness and identity difference becomes critical because identities are consequential for legitimacy [71,75].

Besides sameness and distinctiveness, the construction of legitimacy also requires cognitive and socio-political processes. Cognitive legitimation comes from the spread of knowledge about a new venture, while socio-political legitimation is the extent to which key stakeholders, the general public, key opinion leaders, or governmental officials accept a venture as appropriate and right, given existing norms and laws [64]. The first may be assessed by measuring the level of public knowledge about a new activity—the highest form of cognitive legitimation is achieved when a new product, process, or service is taken for granted. In contrast, the second may be measured by assessing the public’s acceptance of the industry, government subsidies to the industry, or its leaders’ public prestige [64].

In the case of SE, however, the processes that led to establishing it as a legitimate category are not deeply understood. In this context, a historical examination of the evolution of the category, as portrayed by several stakeholders, can identify these formation processes. This is the focus of our analysis.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

To conduct a historical analysis, that is, to establish when, how, and by whom the SE category was formed, we compiled data from several publicly available sources: the scientific community, analysts, governmental organisations, international organisations, and other interested audiences. The rationale for searching for a wide range of stakeholders and not merely concentrating, for example, on the scientific community’s contribution, was related to the scope of our two research questions. Since the literature on how categories are formed and stakeholders grant legitimacy advocates there must be an analysis of how “external audiences” (comprising a vast panoply of societal agents, actors, stakeholders) judge their feasibility, viability and ultimately confer legitimacy, hence, playing different roles in the formation of the category and granting various types of legitimacy, we followed a strategy of searching and compiling the most heterogeneous range of external audiences possible from different quadrants of society. The aim was to qualitatively observe, analyse their content and subsequently extract the most relevant material that would support us in deducing how each of these would surface, define, describe and confer legitimacy to a new phenomenon—the SE and its constituent entities—and consequently, the formation of the SE as a legitimate category.

The initial source we used was Sundararajan’s [76] book “The Sharing Economy: The end of employment and the rise of crowd-based capitalism.” This source is relevant because the author reveals some possible historical roots that lead to today’s SE. From this specific source, we then progressively searched for other publicly available sources by searching various online platforms, such as Google, Google Scholar, Research Gate, Scopus and Web of Science using the keyword “sharing economy” and other equivalent expressions such as “collaborative economy,” “collaborative consumption,” “access-based consumption,” “connected consumption,” “peer-to-peer,” “sharing paradigm,” “crowdsourcing” or “sharing business.” At the end of this process, we ended up with a collection of contributions (corresponding to a gross total of 32 sources and 2433 pages read) from diverse stakeholders, such as the scientific community (with 81% of analytical importance)—[3,19,20,31,32,40,47,48,49,50,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92]—analysts (6% of analytical importance)—[29,93] governmental organizations—(3% of analytical importance) [94,95,96]; international organizations and organisms (6% of analytical importance)—[97,98,99]; and other interested audiences (3% of analytical importance)—[100].

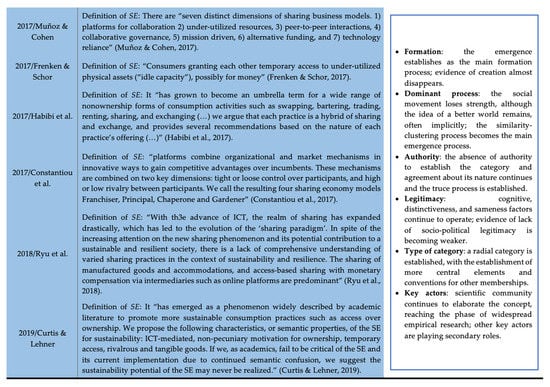

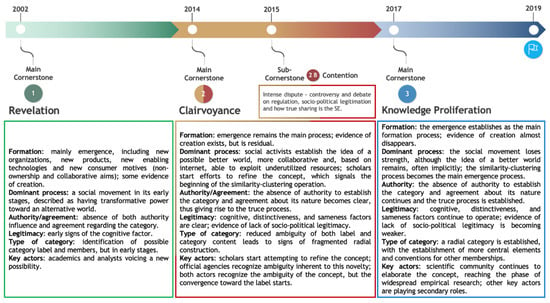

We started by distilling and depicting 28 key ideas and conceptualisations of the SE and related labels, chronologically ordered, to grasp how the meaning evolved. Although this time-based ordering is essential to our analysis, we are aware that publication dates do not correspond precisely to the time of the authors’ thought. Moreover, close dates can largely overlap, inhibiting the detection of a clear shift in evolution. Despite these limitations, we believe that a chronological display is the best approach to answer how the SE as a category has been formed and evolved. This timeline also enabled us to become aware of the approximate moment in which different stakeholders played an important role, from the beginning of using the SE term until its institutionalisation in commonly accepted language, a momentous event represented by its inclusion in the Oxford Dictionary in 2015. This analysis also enabled us to list the SE related terms, or competitive labels, like collaborative consumption, access-based consumption, or connected consumption.

3.2. Data Analysis and Interpretation

Once the timeline was established and considering that the study’s primary purpose was to analyse the process underlying the formation of a new category, we interpreted all definitions and related meaning provided by authors. We fine-tuned our interpretation by reading the entire documents and searching for complementary meanings to contextualize the SE formation. In essence, we applied a qualitative method in which we observed, content analysed, and subsequently, extracted relevant material from the data reported in the documents, and the literature that would resonate as describing the various category formation processes we had previously identified in the contextual scientific literature about how categories are formed and legitimacy is granted. Thus, in attaching meaning to SE, we used several theoretical sources, namely Durand and Khaire’s [10] distinction between category formation by creation or emergence; the dominant processes of emergence of social-movement or similarity clustering as suggested by Wheaton and Carroll [11]; Rhee et al.’s [12] influence of authority and agreement between actors, generating the processes of proof, consensus, fiat and truce; Navis and Glynn’s [56] legitimacy granting processes of sameness or close substitution and distinctiveness; and Aldrich and Fiol’s [64] cognitive and sociopolitical approach. In searching for evidence about these different processes describing category formation, we attempted to identify an evolution pattern in which different actors and different processes played distinct roles in forming the SE category. Finally, we used Rosch’s [15,16] and Mervis and Rosch’s [17] prototype and Lakoff’s [13], Lakoff and Johnson’s [14] metaphorical approaches to categories in an attempt to grasp the type of the SE as a nascent category.

4. Results

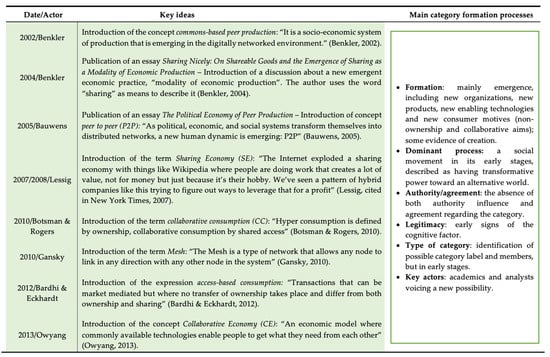

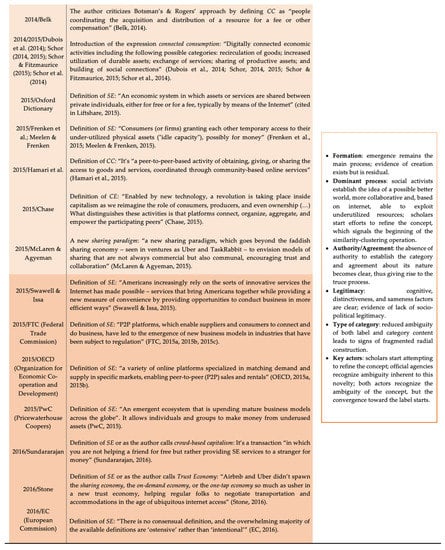

The gross overall results (Figure 1) demonstrate that it can be traced to a timeline ranging from 2002 to 2019. Moreover, we identify a pattern in the evolution of the conceptualisation of the SE with some fundamental cornerstones. The first of these is in 2002, the first time someone broached the theme in the Era of the Internet (Benkler’s [77] contribution with the introduction of the concept “commons-based peer production”). The second one occurs in 2014, when there was a rise of multiple SE practices together with the first substantial discussions on the SE (represented by Belk’s [19] contribution in criticising Botsman and Rogers’s [31] book “What’s mine is yours: The rise of the Collaborative Consumption”). We may dissect this second cornerstone into one sub-cornerstone: in 2015, which we believe to be the beginning of intense debate around the regulation of the SE, represented by Swawell and Issa’s [93] launch of The Congressional Sharing Economy Caucus. We identify the third cornerstone in 2017, which benchmarks a new phase (ranging from 2017 to 2019) characterised by an unprecedented number of scientific articles on the SE, whose main common trends of thinking were around finding a settling discourse around the SE (some examples are Muñoz and Cohen [3]; Frenken and Schor [47]; Ryu et al. [91]; and Curtis and Lehner [92]).

Figure 1.

Gross overall results—key ideas, chronologically ordered, from different actors in establishing the sharing economy (SE) as a legitimate category.

Although these cornerstones are indicative, in the sense that they do not mean to represent specific dates, they are informative in supporting an attempt to identify phases in the processes of the formation of the SE. Moreover, the phases we identify are not entirely discrete, in the sense that the same processes can operate in different stages but with different emphases.

- Phase 1. The revelation: activists disclose the possibility of a better world

The very first overall observation derived from our analysis is the identification of clear main phases in the formation and evolution of the SE as a category. Although we can extend it until 2016, the first main phase is mainly concentrated between 2002 and 2013. This phase can be named the “Revelation”. Key actors are mostly ‘general analysts’ and some academics like Lessig [79] (in 2007/2008) and Benkler [20,77] (in 2002, 2004), who seek to make sense of a new phenomenon, even though not based on empirical studies, and are concerned about suggesting a name for it. Because they are in the very early stages of a new phenomenon, there is no consensus about the label and the aspects of the situation covered. For instance, Benkler [77] (in 2002) and Bauwens [78] (in 2005) use different labels (commons-base peer production and peer to peer production, respectively) to describe a similar novel economic system in which people can exchange outside the common capitalist system. It is, at the same time, the reconnaissance of a new reality, but also a suggestion of an alternative better future, in which people can share resources and experiences to their advantage, sometimes without searching to maximise individual profits, as noted by Lessig [79] (in 2007/2008), the author to whom the SE label is attributed. Labels can become subcategories of broader overarching categories, like the suggestion of the “collaborative economy,” a new economic model that can include the newly popularised term “shared economy,” as pointed out by Owyang [80] (in 2013). Illustrative quotes are:

“It is a socio-economic system of production that is emerging in the digitally networked environment. Facilitated by the technical infrastructure of the Internet, the hallmark of this socio-technical system is a collaboration among large groups of individuals, sometimes in the order of tens or even hundreds of thousands, who cooperate effectively to provide information, knowledge, or cultural goods without relying on either market pricing or managerial hierarchies to coordinate their common enterprise (…) examples: GNU/Linux operating system, the Apache webserver, Perl and BIND (…) SETI (…) Clickworkers (…) Wikipedia (…) Slashdot (…) Kuro5hin (…) Open Directory Project“ [101] (pp.394–400); and “As political, economic, and social systems transform themselves into distributed networks, a new human dynamic is emerging: P2P”. This new dynamic is giving rise to “a third mode of production, a third mode of governance, and a third mode of property” and, ultimately, “it is poised to overhaul our political economy in unprecedented ways” [78] (p. 33).

This new world is made possible by the Internet 2.0, a technology that enables evolution to a more tied global community (Botsman and Rogers [31]—in 2010), and opening new exchange possibilities including business, as highlighted by Gansky [32] (in 2010). In this new world, classical external constraints like advertising, market price, or managerial hierarchies can now be replaced by active consumers pursuing their motivations. Consumption and ownership can be separated in people who do not define themselves by their possessions but by the possibility to share access to consumption. Variously labelled, this new reality encompasses a vast array of elements, such as individual consumers, hybrid companies, entire economic systems, or peer-to-peer projects.

- Phase 2. Clairvoyance: scientific community searches for clarification while official organisations seek peace

Some proposals made by authors included in the “Revelation” phase faced serious challenges from new actors. Therefore, a new (second) main phase took place, named the “Clairvoyance” phase. Although there are exact overlaps in terms of dates, we believe that significant events from 2014 to 2016 represent a qualitative shift in SE formation. Two key actors, each owning its power base, played critical complementary roles in this move: scholars attempted to discuss and refine the concept. At the same time, official agencies recognised the ambiguities but assumed the label. Contributions made by Schor [48] (in 2014), Schor and Fitzmaurice [83] (in 2015), and Schor et al. [84] (in 2014) are good examples of the conceptual refinement process initiated during this period. An illustrative quote is:

“Digitally connected economic activities including the following possible categories: recirculation of goods (i.e., Craigslist, eBay); increased utilisation of durable assets (i.e., Zipcar, Relay Rides, Uber, CouchSurfing, Airbnb); exchange of services (i.e., Time banking, TaskRabbit, Zaarly); sharing of productive assets; and building of social connections (i.e., Mama Bake, Soup Sharing, and EatWithMe)”. The critical distinguishing elements are: “(a) the ability of facilitating exchange among strangers rather than among kin or within community; (b) the strong reliance on technology that may also favor offline activities; and (c) the participation of high cultural capital consumers rather than being limited to a survival mechanisms among the most disadvantaged (as was mostly the case for older forms of sharing and collaborative consumption), as it remains for some socially oriented current not for profit initiatives” (Dubois et al., Schor, Schor and Fitzmaurice, and Schor et al. cited in [99], p. 6).

Schor [48] (in 2014) not only questions the motivations of people involved in SE activities but also raises a vital categorisation question when stating that most commercial platforms included do not belong there. In line with the process of category meaning refinement, authors engage in the discussion of what types of activities and organisations should be included, such as those that re-circulate goods that increase the use of durable assets, as well as the critical dimensions that can be used as bases for other classificatory activities, like the ability to facilitate exchange among strangers or the participation of high cultural capital consumers. Frenken et al.’s [85] (in 2015) and Meelen and Frenken’s [86] (in 2015) definition, although shorter, also entails the effort to identify critical defining elements, despite the purpose underlying the exchange activity, namely for profit or not. The search for good examples of what the SE is, is a core element characterising this phase. It seems that the label is being widely shared, but the discussion about the features remains.

This “Clairvoyance” phase includes a specific feature: the rise of controversy and debate on regulation and how far the SE is real sharing. This dispute involves the role of official agencies in stabilising the label, despite recognising several ambiguities regarding its elements and criteria for inclusion. Concerned about competition, consumer protection, and other economic issues raised by the SE, in 2015, the US Federal Trade Commission [94,95,96] refers to “P2P platforms which enable suppliers and consumers to connect and to do business, have led to the emergence of new business models and industries that have been subject to regulation”. In the same year, the OECD [97,98] does not present a specific definition but refers to “a variety of online platforms specialised in matching demand and supply in specific markets, enabling peer-to-peer sales and rentals.” The label seems to be assumed. Still, the inclusion requirements are left open enough to avoid entering into the discussion. During the same period, the European Commission [99] (in 2016) issued a comprehensive report, based on a review recognising that there are “ambiguous answers to some of the fundamental questions about the sharing economy,” and that the field requires policy attention, especially regarding regulatory, consumer protection, and unfair competition issues. Illustrative quotes are:

“No single label can neatly encapsulate the movement, as for some the word ’sharing´ was a misnomer, a savvy-but-disingenuous spin on an industry they felt was more about economic opportunism than altruism, while for others, more appropriate titles included the Trust Economy, Collaborative Consumption, the On-Demand or Peer-to-Peer Economy” [23] (p. 14); “Together, these companies have come to embody a new business code that has forced local governments to question their faithfulness to the regulatory regimes of the past” [90] (p. 10); and “there still are ambiguous answers to some of the fundamental questions about the ‘sharing economy’ (…) (a) there is no consensual definition and (b) the overwhelming majority of the available definitions are ‘ostensive’ rather than ‘intentional’” [99] (pp. 3–7).

The result of this convergence process can be observed in SE entering the Oxford Dictionary [100] (in 2015), according to which SE refers to “an economic system in which assets or services are shared between private individuals, either for free or for a fee, typically by means of the Internet.” As happened, for example, with the OECD approach, the label is coined. Still, the definition is left open enough to accommodate great variability regarding the category’s members and their motives.

It should be noted that some key ideas included in the “Revelation” phase can also be observed in the “Clairvoyance” phase. Several authors issue books calling people’s attention to a new world being constructed. This is the case of McLaren and Agyeman’s [89] (in 2015) propositions of a new, broader and more inclusive framing for the SE, named “sharing paradigm,” Sundararajan’s [76] (in 2016) book about the end of employment and the rise of crowd-based capitalism, and Stone’s [90] (in 2016) book about how Uber, Airbnb, and killer companies of the New Silicon Valley are changing the world.

- Phase 3. Knowledge proliferation: scientific community takes over and sharing economy becomes a research object

In our view, the period from 2017 to 2019 also represents a clear shift in the SE formation—a new third main phase. In this phase, we see the SE label being globally adopted, and original proponents of related terms as labels for a new world losing prominence, the same happening with official agencies, and a straightforward take over from academia. We call this the “Knowledge Proliferation phase.” An illustrative quote is:

“Sharing of resources, goods, services, experiences, and knowledge is one of the fundamental practices that has been widely embedded in human nature. With the advance of information and communication technology, the realm of sharing has expanded drastically, which has led to the evolution of the ‘sharing paradigm.’ Despite the increasing attention on the new sharing phenomenon and its potential contribution to a sustainable and resilient society, there is a lack of comprehensive understanding of varied sharing practices in the context of sustainability and resilience. This study maps out the academic landscape of sharing and examines what and how we share by a systematic literature review. We discuss research gaps in sharing paradigm studies and the potential contribution of sharing in building sustainable and resilient societies. Our results show regional and sectoral imbalances in the sharing studies. The findings also illustrate that sharing manufactured goods and accommodations and access-based sharing with monetary compensation via intermediaries such as online platforms are predominant. Our evaluation provides a bird’s-eye view of existing sharing studies and practices, enabling the discovery of new opportunities for sustainable and resilient societies. Beyond sharing businesses, we need to have a closer look at how our nature of sharing is linked to sustainability and resilience of our societies” [91] (p. 515).

In 2017, Muñoz and Cohen [3] published a paper mapping out the SE with special attention to existing business models. Frenken and Schor [47] (in 2017) provided an overview of the concept, refining its nature, and also discussing future possibilities. Other scientific articles progressively came to light, their main focus being to contribute to settling the discourse around the SE, particularly (i) identifying and arranging its main activities, practices, and businesses, (ii) explaining its implications, impacts and effects, and (iii) bringing the theme into the sustainability field. Examples of this trend are Habibi, et al. [50] (in 2017); Constantiou, et al. [49] (in 2017); Ryu, et al. [91] (in 2018); Curtis and Lehner [92] (in 2019). Today, academia is mostly focused on contributing to further theoretical and empirical refinement of the current literature. The profusion of research has led to comprehensive review work, such as that of Laurenti et al. [102] (in 2019).

5. Discussion

This research’s overriding goal was to investigate how the SE was formed and evolved as a legitimate category. Our analysis reveals a sequential category construction process involving three phases: the revelation, clairvoyance, and knowledge proliferation. Initiated as a social movement with a subsequent take over by a similarity clustering process, with different actors playing distinct roles with rapid adoption and institutionalisation by official entities and fast integration by the academic community as a new subject that deserves attention; all this despite the lack of consensus between actors and the questionable awareness of the category by the members themselves and the general public. Key actors are aware of the ambiguity around membership of the SE, but this possible divide did not prevent the label’s widespread use. As a category, the SE is performing the essential functions of these fundamental cognitive devices: it allows humans to deal with the vast diversity of initiatives, events, and ideas that characterise this new phenomenon, thus assuring basic collective sense-making and communication functions while maintaining enough cognitive flexibility to accommodate novelty and not prevent development [13,14,15,16,17]. As a category in formation, the SE is a unique cognitive framework guiding how different stakeholders evaluate new organisations and their products, determines expectations regarding organisational actions, and enables both material and symbolic exchanges [55].

In the first instance, regarding how the SE has been forming and evolving as a category through time, we note a timeline ranging from 2002 to 2019. We suggest that this evolution may be split into three distinct main phases representing different formation processes. Figure 2 summarises our proposition.

Figure 2.

Timeline evolution of the formation of the SE as a category.

The first main phase—Revelation—is the primordial period of conceptualisation and cognition. It is a phase mainly characterised as being full of significant dazzle, appeal and fascination, revealing that we were in the presence of a new phenomenon disrupting the preceding status-quo as if announcing the solution to heal the world and turn it into a fairer, wiser, equable, rational, well balanced and more sustainable one—a solution defending the interests of what Lindenberg and Foss [103] call a “supra-individual entity” with collectivistic, normative and altruistic concerns towards more communal causes; in other words, a solution goal-orientated around the “We,” “a collective self, oriented toward acting appropriately in an exemplary fashion in terms of what is good for the collective goals” [103] (p. 505).

This phase’s critical formation process is emergence, although some signs of creation are present [10]. This emergence of a new reality was led by activists, indicating a social movement process [11]. At a very early stage, no actor emerged as having the authority to impose the category. The lack of consensus among actors regarding both the label and the content was evident, paving the way for future truce processes [12].

The second main phase, clairvoyance, represents a clear shift in the formation of the SE. This is a period where there is a consolidation of cognition penetration and diffusion into society. It is a phase mainly characterised and benchmarked by the emergence of critical discussion in questioning SE’s true nature and identifying various prototypical activities. It is a more sceptical, less glamorous, and more grounded phase as if the announced solution to heal the world was a mere illusion and some analysts and scholars began to come to terms with the harsh reality, becoming more discerned, and realising that this new SE disruptive paradigm had brought with it many more layers, rather than just being a noble service of a supra-individual entity. The SE seems to be a mere pretext for a vast spectrum of individualistic and opportunistic stakeholders (i.e., incumbents, start-ups, various types of businesses, customers, etc.) to come into play and gain benefits from their involvement (selfish exploitation of an opportunity without any kind of collectivist concerns about contributing to others’ welfare and participating in something that is for the good of society and the community as a whole). The various agents, particularly businesses and customers/users, participate in the SE because their goal orientation is around the I, either with hedonic or gain purposes discarding normative or collective-oriented motivations [103].

This second phase includes contention elements, representing controversy and debate on regulation and socio-political legitimation and how real SE sharing is. In this phase, we notice the increase in the number of stakeholders involved in the discussion, mainly with official organisations entering the scene and activists and scholars. Altogether, the clairvoyance phase represents a period dominated by a debate on the content, but the SE label tends to stabilise. The critical formation process is emergence [10], with the social movement explanation starting to lose its prominent role, as happened in the revelation phase, due to the arrival of more academic scrutiny, indicating a shift to a similarity-clustering process [12]. In the absence of authority from specific key actors to impose the category and the presence of profound disagreement about the nature of the category, the truce process [12] enables the accommodation of ambiguity without preventing development.

The third main phase, knowledge proliferation, is mainly characterised by a high number of scientific articles, whose primary focus is to help settle the discourse around the SE, particularly identifying and arranging its main activities, practices and businesses. This is the effect of the scientific community’s predominant role. In this phase, the SE becomes a research object, and activists and official agencies become secondary players in understanding and communicating what the SE is. The primary category formation process is emergence [10], and perhaps due to the prominent role of researchers, evidence of creation is now absent. Thus, similarity clustering becomes the dominant process of emergence. As observed in the clairvoyance phase, the truce process allows key actors to continue to talk about the SE, although the lack of consensus regarding the meaning and content of this new trend remains evident.

Complementarily, we foresee the possibility of forming a new phase that may currently be under construction (from 2020 onwards) and may lead to further developments in clarifying and settling the whole contention discourse initiated in 2015.

Altogether, our analysis contributes to the existing literature on the formation of categories because the SE is a case that does not fall into just one, significantly narrowed process. Instead, we are in the presence of multiple processes of diverse natures that are intertwined, with each one being dominant in distinct phases.

Regarding whether the SE is a new legitimate category, we used the data to support the generalised legitimacy granted to the SE. Several products and services are perceived to be of the same type in satisfying market demand and grouped as members of that same category, thus meeting the sameness requirement for legitimacy [56]. On the other hand, not all members are equal within the category, corresponding to the distinctiveness requirement [56]. Signs of public knowledge of this new activity and its products and services abound [29], which supports the cognitive need for legitimacy [64]. The debate around the appropriateness of some organisations usually included in the SE, namely Uber, is far from closed, which is an indication that socio-political legitimation is currently under construction.

The SE’s nature seems to fall into the metaphorical approach of how categories are structured, particularly the notion of radial categories [13,58]. These categories include central and less central members whose features cannot be inferred from the central ones’ characteristics. Non-central elements’ attributes have to be determined, usually metaphorically, by convention or institutionalised agreements between relevant actors. Thus, consistent with the truce process previously highlighted [12], the SE gives us a cognitive infrastructure to understand this new reality as a radial category. Still, it does not prescribe limits for inclusion, which allows the extension and change of the category by a succeeding process of collective sense-making and entrepreneurship.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study is not without limitations. First, the literature we used to map the evolution of the SE did not come from a systematic search of both academic and non-academic sources, limiting the scope of our analysis by leaving important constitutions out of the corpus. In addition, our findings do not reveal clear, finite, separated periods. We believe that the definite establishment of these milestone events will be impossible to ascertain. That is to say, as the SE’s consolidation as a category shows signs of still being a continuous process of evolution, it is more than predictable that new milestone events may arise in its evolution. Finally, entrepreneurs of the several forms of SE projects were left out of the analysis, which lessens understanding of the category formation process. However, we suspect that in the early stages of category formation, with the characteristics we identify in the SE, the label itself is not a feature for those who are involved in launching new ventures. Indeed, this will not be the case when starting new ventures in well established categories, such as private versus non-profit organisations. Entrepreneurs can claim category membership on which to base their organisations’ identity.

In the same way, customers of several types of offers made by SE organisations were not analysed. The motivations underlying consumption decisions, especially when compared to substitutes from non-SE, could be subject to study. Besides addressing these issues, future research could shed light on the interaction processes by which different stakeholders craft a category based on a truce, considering that actors engage in reciprocal influence processes.

6. Conclusions

Keeping in mind our research questions—(RQ1) how the SE was formed and evolved as a category; and (RQ2), as a category, is the SE legitimate?—our findings reveal that the SE is arising (associated mainly with emergence formation processes, comprising social movement, similarity clustering, and truce components) as a new legitimate category, even though it still lacks a degree of socio-political legitimation.

Moreover, from a perspective of how categories are structured, our results reveal that the nature of the SE seems to fall into a metaphorical approach, particularly the notion of radial categories, where there is a growing truce in conventionally agreeing to use the metaphor “sharing economy” to refer to a wide range of apparently divergent, contradictory, paradoxical, opposite categories and subcategories. This is why we have been witnessing major, sometimes, inconclusive discussions, interpretations amongst diverse stakeholders about what the SE really is (how it should be addressed). This unsettled discourse has, therefore, been contributing to an increasing number of stakeholders interested in this discussion, as well as affecting and changing the way those stakeholders have been communicating with each other.

In short, this study offers an additional layer in making sense of the SE from a category formation standpoint. It highlights how the category of the SE was formed, evolved, and the legitimacy gained. It can serve as another vital benchmark in grasping the reasons for the impressive growth of the SE in recent years across the globe.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.C., F.N.; methodology, J.M.C., F.N.; validation, F.N.; formal analysis, J.M.C.; investigation, J.M.C.; resources, J.M.C., F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.C.; writing—review and editing, J.M.C., F.N., R.L.; visualization, J.M.C., F.N., R.L.; supervision, F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cohen, B.; Kietzmann, J. Ride On! Mobility Business Models for the Sharing Economy. J. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knote, R.; Blohm, I. Deconstructing the Sharing Economy: On the Relevance for IS Research. In Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik (MKWI); Ilmenau: Göttingen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, P.; Cohen, B. Mapping out the Sharing Economy: A Configurational Approach to Sharing Business Modeling. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lee, S. Adaptive governance and decentralization: Evidence from regulation of the sharing economy in multi-level governance. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court of Justice of the European Union. The Service Provided by Uber Connecting Individuals with Non-Professional Drivers is Covered by Services in the Field of Transport; Judgment in Case C-434/15 Press and Information Asociación Profesional Elite Taxi v Uber Systems Spain SL. Available online: https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2017-12/cp170136en.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Observador. Tribunal de Justiça Europeu Decide: Uber é Uma Empresa de Transportes e tem de Cumprir com a Legislação em Vigor. Available online: https://observador.pt/2017/12/20/tribunal-de-justica-europeu-decide-uber-e-uma-empresa-de-transportes-e-tem-de-cumprir-com-a-legislacao-em-vigor/ (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Whetten, D.A.; Mackey, A. A Social Actor Conception of Organizational Identity and Its Implications for the Study of Organizational Reputation. Bus. Soc. 2002, 41, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, R.C.; Geleilate, J.M.G.; Rong, K. The Sharing Economy Globalization Phenomenon: A Research Agenda. J. Int. Manag. 2018, 24, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, R.; Khaire, M. Where Do Market Categories Come From and How? Distinguishing Category Creation from Category Emergence. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, D.R.; Carroll, G.R. Where did “Tex-Mex” come from? The divisive emergence of a social category. Res. Organ. Behav. 2017, 37, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, C.; Dantes, R.; Epstein, L.; Murphy, D.J.; Seymour, C.W.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Kadri, S.S.; Angus, D.C.; Danner, R.L.; Fiore, A.E.; et al. Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009–2014. JAMA 2017, 318, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakoff, G. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live By; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch, E. Principles of categorization. In Cognition and Categorization; Rosch, E., Lloyd, B., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1978; pp. 27–48, Reprinted in Fuzzy Grammar. A Reader; Aarts, B., Denison, D., Keizer, E., Popova, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch, E. Human categorization. In Studies in Cross-Cultural Psychology, Vol. 1; Warren, N., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1977; pp. 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mervis, C.B.; Rosch, E. Categorization of natural objects. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1981, 32, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zifkin, A. Interview. Politik Media Inc. 2015. Available online: http://www.politik.io/articles/the-sharing-economy/ (accessed on 16 June 2016).

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkler, Y. Sharing nicely: On shareable goods and the emergence of sharing as a modality of economic production. Yale Law J. 2004, 114, 273–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The New York Times. A Boston Newspaper Prints What the Local Bloggers Write. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/07/business/media/07boston.html (accessed on 11 August 2017).

- Malhotra, A.; Van Alstyne, M. The dark side of the sharing economy… and how to lighten it. Commun. ACM 2014, 57, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Bardhi, F. The Sharing Economy Isn’t About Sharing at All—HBR. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar]

- Teubner, T. Thoughts on the Sharing Economy. In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Commerce, Hong Kong, China, 1–2 May 2014; Volume 11, pp. 322–326. [Google Scholar]

- Geron, T. Airbnb and the Unstoppable Rise of the Share Economy; Forbes: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, S.; Summers, L.H. How Uber and the Sharing Economy Can Win Over Regulators—HBR. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 13, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tabcum, S. The Sharing Economy Is Still Growing, and Businesses Should Take Note. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeslacouncil/2019/03/04/the-sharing-economy-is-still-growing-and-businesses-should-take-note/#781918874c33 (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Penn, J.; Wihbey, J. Uber, Airbnb and Consequences of the Sharing Economy: Research Roundup. Available online: http://journalistsresource.org/studies/economics/business/airbnb-lyft-uber-bike-share-sharing-economy-research-roundup (accessed on 18 June 2016).

- PwC. The Sharing Economy. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/us/en/technology/publications/assets/pwc-consumer-intelligence-series-the-sharing-economy.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2016).

- Belk, R. Sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gansky, L. The Mesh: Why the Future of Business Is Sharing; Portfolio Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberton, C.; Rose, R. When is ours better than mine? A framework for understanding and altering participation in commercial sharing systems. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, A.; Grayson, K. The intersecting roles of consumer and producer: A critical perspective on co-production, co-creation and prosumption. Sociol. Compass 2008, 2, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, C., Jr.; Schau, H. Culture and co-creation: Exploring consumers’ inspirations and aspirations for writing and posting online fan fiction. In Consumer Culture Theory: Research in Consumer Behavior; Belk, R., Sherry, J., Jr., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 11, pp. 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences the net practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G.; Jurgenson, N. Production, consumption, prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer’. J. Consum. Cult. 2010, 10, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffler, A. The Third Wave; William Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mont, O. Clarifying the concept of product-service system. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G. Access based consumption: The case of car sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, J. Consumer participation and productivity in service operations. Interfaces 1985, 15, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, H. Emerging sources of labor on the Internet: The case of America online volunteers. Int. Rev. Soc. Hist. 2003, 48, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquier, A.; Daudigeos, T.; Pinkse, J. Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: An organizing framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 125, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L. Performing the sharing economy. Geoforum 2015, 67, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]