CSR, Co-Creation and Green Consumer Loyalty: Are Green Banking Initiatives Important? A Moderated Mediation Approach from an Emerging Economy

Abstract

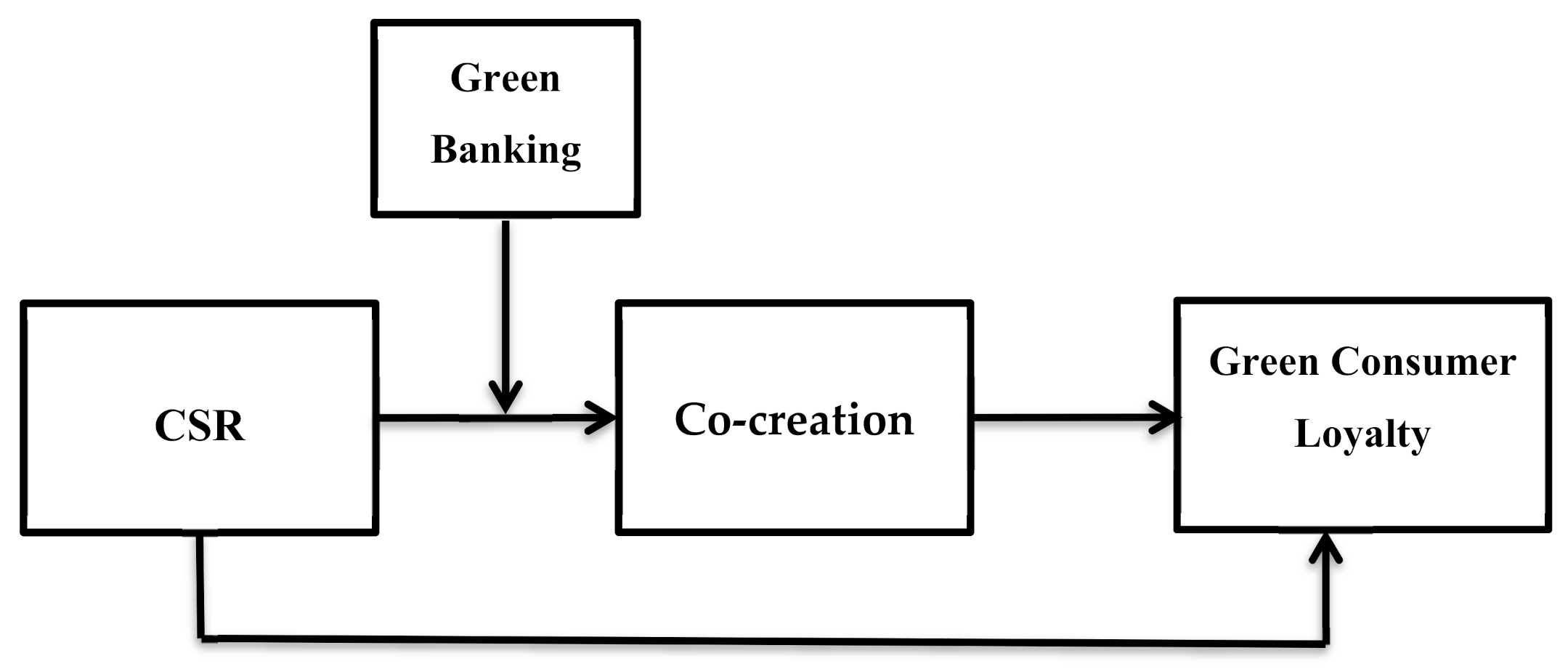

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. CSR and Co-Creation

2.2. Co-Creation and Consumer Loyalty

2.3. CSR and Consumer Loyalty

2.4. Co-Creation as Mediator

2.5. Green Banking Initiatives as a Moderator

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling Procedure and Strategy

3.2. Measures

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Handling of Social Desirability

4.2. Common Method Variance

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Implications and Suggestions

- (1)

- Banks need environmental impact assessment as part of the bank’s overall consumer assessment (especially corporate consumers) before granting a loan if the consumer re-examines the environmental risk model and assesses the environmental impact of the consumer’s business.

- (2)

- Green offices should be established in order to implement the green banking guidelines and to introduce environmental culture as part of the organizational culture.

- (3)

- The recycling of office waste using a recycling environment should be encouraged.

- (4)

- An environmental campaign needs to be launched in order to commemorate environmental days such as World Water Day, Earth Day and Environmental Day.

- (5)

- Banks should choose ways to eliminate / reduce the use of paper in their day-to-day operations. These steps include a gradual transition to paperless banking.

- (6)

- Banks should install solar energy systems, which will prevent the release of greenhouse gases to reduce environmental degradation.

5.2. Limitations and the Way Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Javed, S.A.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U. Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Ahmad, S.; Islam, T.; Kaleem, A. The nexus of corporate social responsibility (CSR), affective commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour in academia. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatwarnicka-Madura, B.; Siemieniako, D.; Glińska, E.; Sazonenka, Y. Strategic and Operational Levels of CSR Marketing Communication for Sustainable Orientation of a Company: A Case Study from Bangladesh. Sustainability 2019, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abubakr, M.; Abbas, A.T.; Tomaz, Í.V.; Soliman, M.S.; Luqman, M.; Hegab, H. Sustainable and Smart Manufacturing: An Integrated Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samul, J. Spiritual Leadership: Meaning in the Sustainable Workplace. Sustainability 2019, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Chi, X.; Baek, H.; Lee, K.-S. Impact of Environmental CSR, Service Quality, Emotional Attachment, and Price Perception on Word-of-Mouth for Full-Service Airlines. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, S.S.; Roh, T. Taking Another Look at Airline CSR: How Required CSR and Desired CSR Affect Customer Loyalty in the Airline Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Saeed, A.; Iqbal, M.K.; Saeed, U.; Sadiq, I.; Faraz, N.A. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility to Customer Loyalty through Co-Creation and Customer Company Identification: Exploring Sequential Mediation Mechanism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knebel, S.; Seele, P. Introducing public procurement tenders as part of corporate communications: A typological analysis based on CSR reporting indicators. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebmer, C.; Diefenbach, S. The Challenges of Green Marketing Communication: Effective Communication to Environmentally Conscious but Skeptical Consumers. Designs 2020, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, I.; Bossink, B.; Van Der Sijde, P.; Fong, C.Y.M. Why Are Consumers Willing to Pay More for Liquid Foods in Environmentally Friendly Packaging? A Dual Attitudes Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Sabaté, J. Consumer Attitudes Towards Environmental Concerns of Meat Consumption: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tchorek, G.; Brzozowski, M.; Dziewanowska, K.; Allen, A.; Kozioł, W.; Kurtyka, M.; Targowski, F. Social Capital and Value Co-Creation: The Case of a Polish Car Sharing Company. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Singh, J.J. Co-creation: A Key Link Between Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Trust, and Customer Loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 163, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. CSR and Customer Value Co-creation Behavior: The Moderation Mechanisms of Servant Leadership and Relationship Marketing Orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Trimi, S.; Hong, S.; Lim, S. Effects of co-creation on organizational performance of small and medium manufacturers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Chukai, C. Value Co-Creation, Goods and Service Tax (GST) Impacts on Sustainable Logistic Performance. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2018, 28, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N.; Shanmugam, M.; Papagiannidis, S.; Zahay, D.; Richard, M.-O. Branding co-creation with members of online brand communities. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimbaljević, M.; Stankov, U.; Pavluković, V. Going beyond the traditional destination competitiveness—Reflections on a smart destination in the current research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2472–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-S.; Kerr, D.; Chou, C.Y.; Ang, C. Business co-creation for service innovation in the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1522–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Co-creation of service recovery: Utilitarian and hedonic value and post-recovery responses. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Nazir, M.S.; Ali, I.; Nurunnabi, M.; Khalid, A.; Shaukat, M.Z. Investing in CSR Pays You Back in Many Ways! The Case of Perceptual, Attitudinal and Behavioral Outcomes of Customers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Wu, J.; Dao, M. Corporate social responsibility and trade credit. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2019, 54, 1389–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Valiño, P.; Rodríguez, P.G.; Núñez-Barriopedro, E. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty in hypermarkets: A new socially responsible strategy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, H. The Effect of CSR Fit and CSR Authenticity on the Brand Attitude. Sustainability 2019, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Julia, T.; Kassim, S. Exploring green banking performance of Islamic banks vs conventional banks in Bangladesh based on Maqasid Shariah framework. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 11, 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbar, C.; Mahale, P. Impact of Demonetisation on Green Banking. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cui, Y. Green Bonds, Corporate Performance, and Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Da Luz, V.V.; Mantovani, D.; Nepomuceno, M.V. Matching green messages with brand positioning to improve brand evaluation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mendonca, T.; Zhou, Y. Environmental Performance, Customer Satisfaction, and Profitability: A Study among Large U.S. Companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, S.K.; Chenb, J.; Giudicecd, M.; El-Kassar, A.-N. Environmental ethics, environmental performance, and competitive advantage: Role of environmental training. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Dash, G. Environmentally concerned consumer behavior: Evidence from consumers in Rajasthan. J. Model. Manag. 2017, 12, 712–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibe-Enwo, G.; Igbudu, N.; Garanti, Z.; Popoola, T.; Enwo, I. Assessing the Relevance of Green Banking Practice on Bank Loyalty: The Mediating Effect of Green Image and Bank Trust. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Igbudu, N.; Garanti, Z.; Popoola, T. Enhancing Bank Loyalty through Sustainable Banking Practices: The Mediating Effect of Corporate Image. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyeonov, S.; Pimonenko, T.; Bilan, Y.; Streimikiene, D.; Mentel, G. Assessment of Green Investments’ Impact on Sustainable Development: Linking Gross Domestic Product Per Capita, Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Renewable Energy. Energies 2019, 12, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amoako, G.K.; Dzogbenuku, R.K.; Abubakari, A. Do green knowledge and attitude influence the youth’s green purchasing? Theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2020, 69, 1609–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, H.M.A.K.; Herath, H.M.S.P. Impact of Green Banking Initiatives on Customer Satisfaction: A Conceptual Model of Customer Satisfaction on Green Banking. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 21, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Manolas, E.; Tsantopoulos, G.; Dimoudi, K. Energy saving and the use of “green” bank products: The views of the citizens. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, I.; Soretz, S. Green Attitude and Economic Growth. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2016, 70, 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soumya, S. Green banking: A sustainable banking for environmental sustainability. CLEAR Int. J. Res. Commer. Manag. 2019, 10, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassim, B.; Bogers, M. Linking stakeholder engagement to profitability through sustainability-oriented innovation: A quantitative study of the minerals industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; O’Sullivan, P. Corporate social responsibility: Internet social and environmental reporting by banks. Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 414–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeseh, E.; Ako, R.; Okonmah, P.; Obokoh, O.L. Corporations, CSR and Self Regulation: What Lessons from the Global Financial Crisis? Ger. Law J. 2010, 11, 230–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Issock, P.B.I.; Mpinganjira, M.; Roberts-Lombard, M. Modelling green customer loyalty and positive word of mouth. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2019, 15, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Cheng, C.-C. An Empirical Analysis of Green Experiential Loyalty: A Case Study. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2018, 31, 69–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y. Using the sustainable modified TAM and TPB to analyze the effects of perceived green value on loyalty to a public bike system. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 88, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryhun, N.; Kapinus, L.; Petrovych, M. Consumer loyalty assessment as an important means of increasing company’s profitability. Sci. Educ. 2020, 5, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Maqbool, S.; Zameer, M.N. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: An empirical analysis of Indian banks. Future Bus. J. 2018, 4, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servera-Francés, D.; Piqueras-Tomás, L. The effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer loyalty through consumer perceived value. Econ. Res. 2019, 32, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashraf, S.; Ilyas, R.; Imtiaz, M.; Tahir, H.M. Impact of CSR on customer loyalty: Putting customer trust, customer identification, customer satisfaction and customer commitment into equation-a study on the banking sector of Pakistan. Int. J. Multidiscip. Curr. Res. 2017, 5, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Yeh, C.-H. Corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty in intercity bus services. Transp. Policy 2017, 59, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Jan, I.U. The Impact of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Frontline Employee’s Emotional Labor Strategies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ipsen, C.; Goe, R. Factors associated with consumer engagement and satisfaction with the Vocational Rehabilitation program. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2016, 44, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburu, I.A.; Pescador, I.G. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Customer Loyalty: The Mediating Effect of Reputation in Cooperative Banks Versus Commercial Banks in the Basque Country. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Islam, R.; Pitafi, A.H.; Xiaobei, L.; Rehmani, M.; Irfan, M.; Mubarik, M.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty: The mediating role of corporate reputation, customer satisfaction, and trust. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Onrust, M.; Verhoef, P.C.; Bügel, M.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer attitudes and retention—the moderating role of brand success indicators. Mark. Lett. 2017, 28, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gürlek, M.; Düzgün, E.; Uygur, S.M. How does corporate social responsibility create customer loyalty? The role of corporate image. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Intergroup Behavior. Introducing Social Psychology; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 401–466. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.; Austin, C.; William, G.; Worchel, S. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In Organizational Identity: A Reader; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The Multiple Pathways through which Internal and External Corporate Social Responsibility Influence Organizational Identification and Multifoci Outcomes: The Moderating Role of Cultural and Social Orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Gao, Y.; Shah, S.S.H. CSR and Customer Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Customer Engagement. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tuan, L.T.; Rajendran, D.; Rowley, C.; Khai, D.C. Customer value co-creation in the business-to-business tourism context: The roles of corporate social responsibility and customer empowering behaviors. J. Hospit. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gomez, S.; Castro, M.L.A.; López, M.V.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. Where Does CSR Come from and Where Does It Go? A Review of the State of the Art. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Para-González, L.; Mascaraque-Ramírez, C.; Cubillas-Para, C. Maximizing performance through CSR: The mediator role of the CSR principles in the shipbuilding industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2804–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, M.; Vollero, A.; Siano, A. From strategic corporate social responsibility to value creation: An analysis of corporate website communication in the banking sector. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1529–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, J.; Korhonen, A. Value-Creating Stakeholder Relationships in the Context of CSR. In Stakeholder Engagement: Clinical Research Cases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Salvioni, D.M.; Gennari, F. CSR, Sustainable Value Creation and Shareholder Relations. Symph. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2017, 1, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mubushar, M.; Jaafar, N.B.; Ab Rahim, R. The influence of corporate social responsibility activities on customer value co-creation: The mediating role of relationship marketing orientation. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamik, A.; Nowicki, M. Pathologies and Paradoxes of Co-Creation: A Contribution to the Discussion about Corporate Social Responsibility in Building a Competitive Advantage in the Age of Industry 4. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheth, J.N. Customer value propositions: Value co-creation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 87, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurunnabi, M.; Esquer, J.; Munguia, N.; Zepeda, D.; Perez, R.; Velazquez, L. Reaching the sustainable development goals 2030: Energy efficiency as an approach to corporate social responsibility (CSR). GeoJournal 2020, 85, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiliç, M. Online corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in the banking industry. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeninKumar, V. The Relationship between Customer Satisfaction and Customer Trust on Customer Loyalty. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirão, G.; Patrício, L.; Fisk, R.P. Value cocreation in service ecosystems. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Sinarta, Y. Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardes, E.W.; Teixeira, A.; Romano, P.C.D.S. Determinants of co-creation in banking services. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiouras, I.; Skourtis, G.; Giannopoulos, A.; Buhalis, D.; Koniordos, M. Value co-creation and customer citizenship behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mansilla, Ó.; Berenguer-Contrí, G.; Serra-Cantallops, A. The impact of value co-creation on hotel brand equity and customer satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woratschek, H.; Horbel, C.; Popp, B. Determining customer satisfaction and loyalty from a value co-creation perspective. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 40, 777–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambra-Fierro, J.; Pérez, L.; Grott, E. Towards a co-creation framework in the retail banking services industry: Do demographics influence? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.I.; Ahsan, R. Towards innovation, co-creation and customers’ satisfaction: A banking sector perspective. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2019, 13, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Izogo, E.E.; Elom, M.E.; Mpinganjira, M. Examining customer willingness to pay more for banking services: The role of employee commitment, customer involvement and customer value. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-W.; Wang, C.-Y.; Rouyer, E. The opportunity and challenge of trust and decision-making uncertainty: Managing co-production in value co-creation. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 38, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick-Jones, J.K. Social Exchange Theory: Its Structure and Influence in Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Eisingerich, A.B.; Rubera, G.; Seifert, M.; Bhardwaj, G. Doing Good and Doing Better despite Negative Information?: The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Consumer Resistance to Negative Information. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 14, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarmeas, D.; Leonidou, C.N. When consumers doubt, Watch out! The role of CSR skepticism. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1831–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahller, K.A.; Arnold, V.; Roberts, R.W. Using CSR Disclosure Quality to Develop Social Resilience to Exogenous Shocks: A Test of Investor Perceptions. Behav. Res. Account. 2015, 27, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlugun, V.G.; Raboute, W.G. Do CSR Practices Of Banks In Mauritius Lead To Satisfaction And Loyalty? Stud. Bus. Econ. 2015, 10, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shabbir, M.S.; Shariff, M.N.M.; Yusof, M.S.B.; Salman, R.; Hafeez, S. Corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty in Islamic banks of Pakistan: A mediating role of brand image. Acad. Account. Financ. Stud. J. 2018, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, J.; Bigne, E.; Curras-Perez, R. Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility perception on consumer satisfaction with the brand. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2016, 20, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nyuur, R.B.; Ofori, D.F.; Amponsah, M.M. Corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: A developing country perspective. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 61, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyame-Asiamah, F.; Ghulam, S. The relationship between CSR activity and sales growth in the UK retailing sector. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Shahid, Z.; Streimikis, J. The Influence of a Firm’s CSR Initiatives on Brand Loyalty and Brand Image. J. Compet. 2020, 12, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkitbi, S.S.; Alshurideh, M.; Al Kurdi, B.; Salloum, S.A. Factors Affect Customer Retention: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics, Cairo, Egypt, 19–21 October 2020; pp. 656–667. [Google Scholar]

- Arli, D.I.; Lasmono, H.K. Consumers’ perception of corporate social responsibility in a developing country. Int. J. Cons. Stud. 2010, 34, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saxton, G.D.; Gomez, L.; Ngoh, Z.; Lin, Y.-P.; Dietrich, S. Do CSR Messages Resonate? Examining Public Reactions to Firms’ CSR Efforts on Social Media. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanclemente-Téllez, J. Marketing and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Moving between broadening the concept of marketing and social factors as a marketing strategy. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2017, 21, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, E.; Bruno, J.M.; Sarabia-Sanchez, F.J. The impact of perceived CSR on corporate reputation and purchase intention. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 28, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mostafa, R.B.; Elsahn, F. Exploring the mechanism of consumer responses to CSR activities of Islamic banks. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 940–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. CSR and consumer behavioral responses: The role of customer-company identification. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, F.; Qayyum, A.; Awan, Y. Impact of Dimensions of CSR on Purchase Intention with Mediating Role of Customer Satisfaction, Commitment and Trust. Pak. Bus. Rev. 2018, 20, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bagh, T.; Khan, M.A.; Azad, T.; Saddique, S.; Khan, M.A. The Corporate Social Responsibility and Firms’ Financial Performance: Evidence from Financial Sector of Pakistan. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Osakwe, C.N.; Yusuf, T.O. CSR: A roadmap towards customer loyalty. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, S.; Iglesias, O.; Singh, J.J.; Sierra, V. How does the Perceived Ethicality of Corporate Services Brands Influence Loyalty and Positive Word-of-Mouth? Analyzing the Roles of Empathy, Affective Commitment, and Perceived Quality. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 148, 721–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossío-Silva, F.-J.; Revilla-Camacho, M.-Á.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Palacios-Florencio, B. Value co-creation and customer loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1621–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Wang, J.-P. Customer participation, value co-creation and customer loyalty—A case of airline online check-in system. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anouze, A.L.M.; AlAmro, A.S.; Awwad, A.S. Customer satisfaction and its measurement in Islamic banking sector: A revisit and update. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 10, 565–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, A.K.; Bae, S.M.; Kim, J.D. Analysis of Environmental Accounting and Reporting Practices of Listed Banking Companies in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bose, S.; Khan, H.Z.; Rashid, A.; Islam, S. What drives green banking disclosure? An institutional and corporate governance perspective. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 501–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Yoshino, N. Sustainable Solutions for Green Financing and Investment in Renewable Energy Projects. Energies 2020, 13, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Julia, T.; Kassim, S. How serious are Islamic banks in offering green financing?: An exploratory study on Bangladesh banking sector. Int. J. Green Econ. 2019, 13, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; Kharel, S.; Devkota, N.; Paudel, U.R. Customers perception on green banking practices: A desk. J. Econ. Concerns 2019, 10, 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Woo, W.T.; Yoshino, N.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Importance of Green Finance for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals and Energy Security. Handb. Green Financ. 2019, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, D.; Waris, I. Eco Labels and Eco Conscious Consumer Behavior: The Mediating Effect of Green Trust and Environmental Concern. Hameed, Irfan and Waris, Idrees (2018): Eco Labels and Eco Conscious Consumer Behavior: The Mediating Effect of Green Trust and Environmental Concern. J. Manag. Sci. 2018, 5, 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- Shampa, T.S.; Jobaid, M.I. Factors Influencing Customers’ Expectation Towards Green Banking Practices in Bangladesh. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 9, 140–152. [Google Scholar]

- Nwagwu, I. Driving sustainable banking in Nigeria through responsible management education: The case of Lagos Business School. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, S.; Thirumaran, R. Consumers’ perception, satisfaction and post purchase behaviour towards green convenience products in Chennai. ZENITH Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.; Ferguson, D.; Pérez, A. Customer responses to CSR in the Pakistani banking industry. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.A.; Khan, Z. Corporate social responsibility: A pathway to sustainable competitive advantage? Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 38, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nysveen, H.; Pedersen, P.E. Influences of Cocreation on Brand Experience. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 56, 807–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.G.; Spreng, R.A. Modelling the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction and repurchase intentions in a business-to-business, services context: An empirical examination. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, E.A.; Dewan, M.N.A.; Chowdhury, M.M.H. Development and validation of a scale for measuring sustainability construct of informal microenterprises. In Proceedings of the 5th Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–18 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, P. Social Desirability Bias. Wiley Int. Enc. Market. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Gliner, J.A.; Morgan, G.A.; Harmon, R.J. Single-Factor Repeated-Measures Designs: Analysis and Interpretation. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2002, 41, 1014–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 357 | 73.0 |

| Female | 132 | 27.0 |

| Age | ||

| 18–20 | 46 | 9.4 |

| 21–30 | 138 | 28.2 |

| 31–40 | 210 | 42.9 |

| Above 40 | 95 | 19.4 |

| Education | ||

| Matric | 39 | 7.9 |

| Intermediate | 78 | 15.9 |

| Graduate | 136 | 27.8 |

| Master | 189 | 38.6 |

| Higher | 47 | 9.6 |

| Unadjusted Correlation | CMV-Adjusted Correlation | |

|---|---|---|

| CSR–CC | 0.514 | 0.511 * |

| CC–GCL | 0.623 | 0.620 * |

| CSR–GCL | 0.492 | 0.491 * |

| CSR–GBI | 0.392 | 0.390 * |

| CC–GBI | 0.421 | 0.419 * |

| GBI–GCL | 0.543 | 0.540 * |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| CSR | This bank is a socially responsible bank | 0.76 |

| This bank is more beneficial to society’s welfare than other brands | 0.88 | |

| This bank contributes to society in positive ways | 0.83 | |

| Co-creation | I often express my personal needs to this brand (bank) | 0.73 |

| I often find solutions to my problems together with my brand (bank) | 0.86 | |

| I am actively involved when the brand (bank) develops new solutions for me | 0.90 | |

| The brand (bank) encourages customers to create new solutions together | 0.77 | |

| Loyalty | I am happy about my decision to choose this product (bank) because of its (environmental) functions | 0.87 |

| I believe that I do the right thing to purchase this product (bank) because of its (environmental) performance | 0.89 | |

| Overall, I am glad to buy this product (bank) because it is (environmentally) friendly | 0.83 | |

| Overall, I am satisfied with this product (bank) because of its (environmental) concern | 0.81 | |

| Green Banking Initiatives | This bank’s (environmental) functions provide very good value for me | 0.82 |

| This bank is very concerned about environmental sustainability | 0.79 | |

| This bank management is serious about green banking projects and willing to finance green projects | 0.86 | |

| The daily operations of our bank are safe for the environment | 0.82 |

| Variable | Items | b FL (Min-Max) | t-Value (Min-Max) | α b | CR b | AVE b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 3 | 0.76–0.88 | 10.08–17.25 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.58 |

| CC | 4 | 0.73–0.90 | 11.72–20.19 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.61 |

| GCL | 4 | 0.81–0.89 | 13.81–21.71 | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.59 |

| GBI | 4 | 0.79–0.86 | 19.76–27.88 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.64 |

| Mean | SD | CSR | CC | GCL | GBI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 3.22 | 1.20 | 0.76 a | |||

| CC | 3.18 | 1.29 | 0.51 ** | 0.78 a | ||

| GCL | 3.76 | 1.06 | 0.49 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.77 a | |

| GBI | 3.49 | 1.11 | 0.39 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.80 a |

| Model—1 | Model—2 | Model—3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect Model | Mediation model | Moderated mediation model | |

| χ2 (df) | 1622.37 (56) | 214.09 (53) | 198.43 (51) |

| χ2/df | 28.97 | 4.04 | 3.89 |

| GFI | 0.822 | 0.926 | 0.942 |

| CFI | 0.798 | 0.903 | 0.976 |

| RMSEA | 0.126 | 0.063 | 0.053 |

| Coefficients | SE | p-Value | 95% Bias | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected CI | |||||

H1: CSR  CC CC | 0.66 | 0.062 | <0.05 | 0.73; 0.79 | Supported |

H2: CC  CL CL | 0.62 | 0.241 | 0.05 | 0.032; 0.21 | Supported |

H3: CSR  CL CL | 0.47 | 0.218 | <0.05 | 0.132; 0.38 | Supported |

| Standardized | 95% Bias | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effects | Corrected CI * | ||

H4: CSR  CC CC  GCL GCL | 0.41 (0.142) * | 0.128–0.802 | Supported |

H4: CSR  CC CC  GCL GCL | 0.54 (0.144) * | 0.137–0.887 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, H.; Rabbani, M.R.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cheng, G.; Zia-Ud-Din, M.; Fu, Q. CSR, Co-Creation and Green Consumer Loyalty: Are Green Banking Initiatives Important? A Moderated Mediation Approach from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10688. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410688

Sun H, Rabbani MR, Ahmad N, Sial MS, Cheng G, Zia-Ud-Din M, Fu Q. CSR, Co-Creation and Green Consumer Loyalty: Are Green Banking Initiatives Important? A Moderated Mediation Approach from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10688. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410688

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Huidong, Mustafa Raza Rabbani, Naveed Ahmad, Muhammad Safdar Sial, Guping Cheng, Malik Zia-Ud-Din, and Qinghua Fu. 2020. "CSR, Co-Creation and Green Consumer Loyalty: Are Green Banking Initiatives Important? A Moderated Mediation Approach from an Emerging Economy" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10688. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410688

APA StyleSun, H., Rabbani, M. R., Ahmad, N., Sial, M. S., Cheng, G., Zia-Ud-Din, M., & Fu, Q. (2020). CSR, Co-Creation and Green Consumer Loyalty: Are Green Banking Initiatives Important? A Moderated Mediation Approach from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability, 12(24), 10688. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410688