Tensions and Opportunities: An Activity Theory Perspective on Date and Storage Label Design through a Literature Review and Co-Creation Sessions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

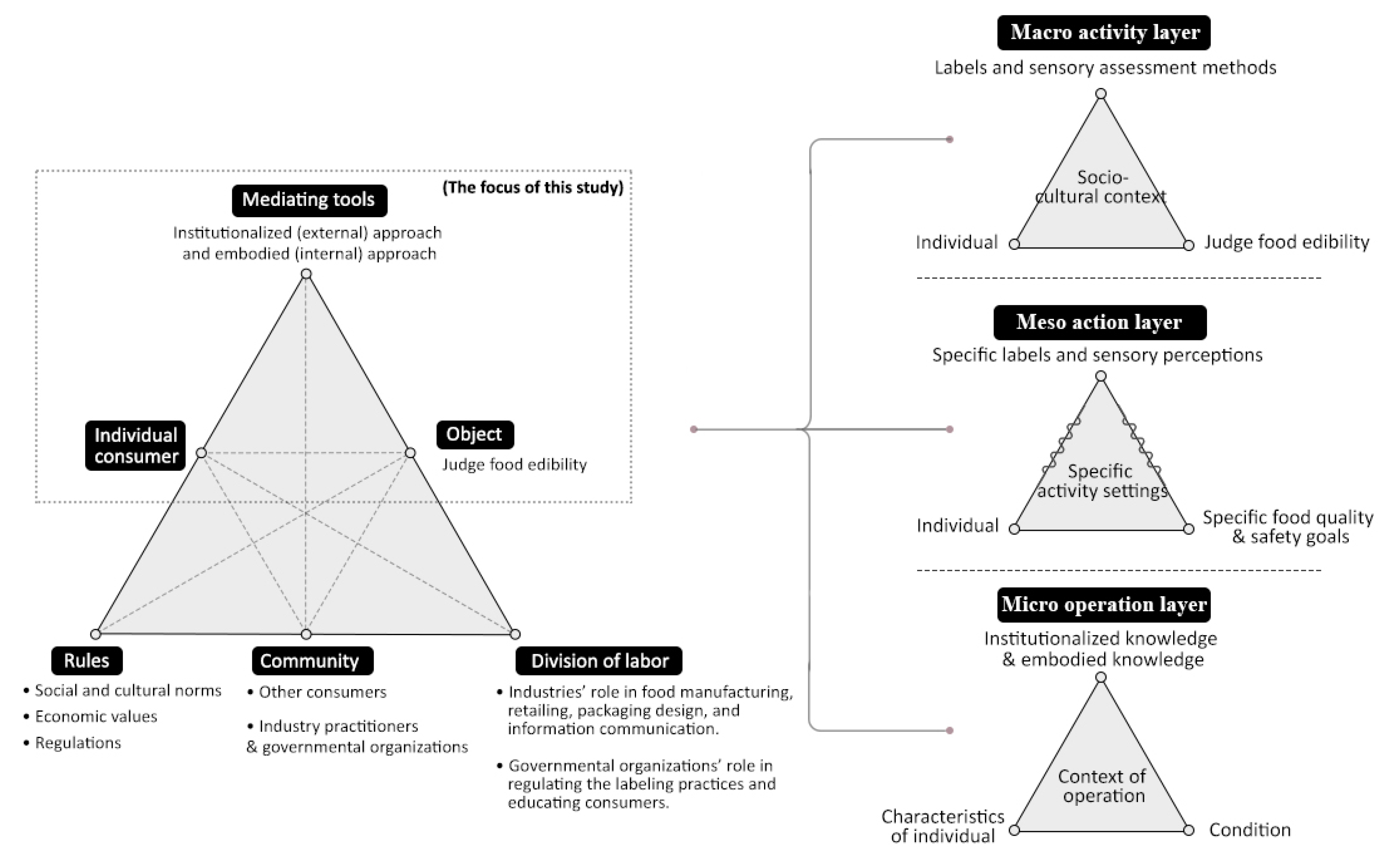

2. Activity Theoretical Lens

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Literature Review

3.1.1. Identification of Research

3.1.2. Study Selection

- S5-I1: The paper focuses on studying date and storage labeling within the scope of consumers’ food assessment, consumer food safety and waste, governmental legislation, packaging design and technology, food retailer and manufacturer practices.

- S5-I2: The paper may not specifically focus on date and storage labeling, but it provides relevant empirical evidence and further discussion of the role that labeling plays in the topics mentioned above.

- S5-I3: The paper may not center on date and storage labeling, but insights and author(s)’ reflections regarding the role that labeling plays can be found in the paper.

- S5-I4: The paper may not specifically focus on date and storage labeling, but discussion regarding the relation between labeling and consumer behavior can be found in the paper. For example, consumer perception of different date labels and how this perception may influence their food assessment.

- S5-E1: The paper only mentions date and storage labeling without further discussion. For example, the term “date label” may be mentioned in the background, results and discussion sections with no follow-up articulation of relevant arguments.

- S5-E2: The paper solely focuses on the technological development or optimization of shelf life and packaging functions that are irrelevant to labeling. This could be a mathematical model to determine food shelf life or a data analysis technique for food quality monitoring.

- S5-E3: The paper explicitly and exclusively focuses on consumer purchase behavior instead of consumer–labeling interaction in household contexts. For example, consumers’ willingness- to-pay for food that is close to or beyond its expiration dates.

3.1.3. Data Extraction and Data Synthesis Procedures

- What is the main research question that the study aims to address and what is the specific research perspective that the study uses to approach the proposed research question? (e.g., food safety, household food waste, consumer food perception, industry practices, legislation);

- What is the overarching research methodology of the paper?

- What is the geographical region of the study (e.g., the UK, US, EU, AU)? And what food product category is taken as the focus of the study (such as fruits and vegetables, meat, dairy products, ready-to-eat products, refrigerated products)?

- What are the key findings of the role that date and storage labeling plays in consumer food edibility judgment?

- What suggestions or proposals for action regarding date and storage labeling are proposed in the study?

3.2. Consumer Workshops and Industry Practitioner Interviews

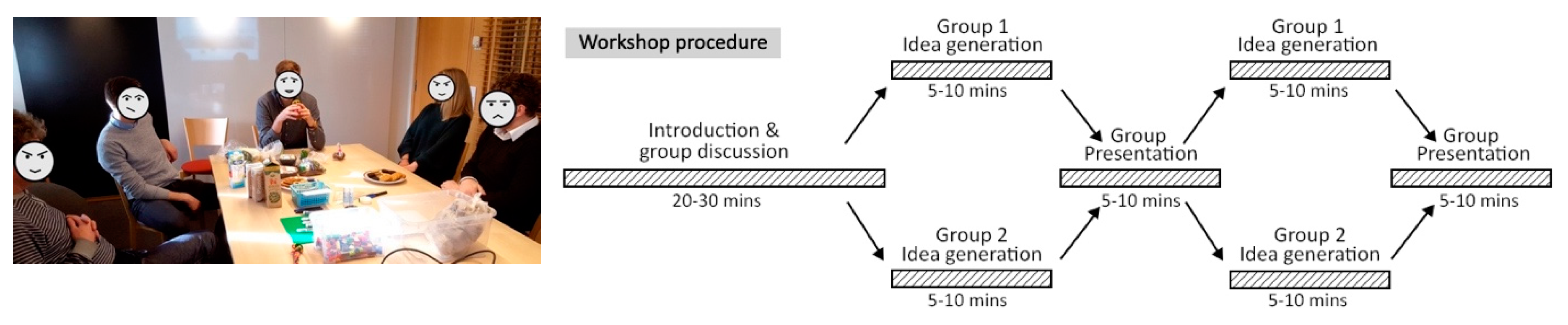

3.2.1. Consumer Workshops

3.2.2. Industry Practitioner Interviews

4. Results of the Literature Review

4.1. An Overview of Date and Storage Labeling Studies

4.2. Compiling Literature Results through an AT Theoretical Lens

4.2.1. Consumers’ Perception and Use of Date and Storage Labels

4.2.2. Consumers’ Embodied Knowledge and Use of Sensory Perceptions in Relation to Date Labels

4.2.3. Tensions within Consumer Interaction with “Use by” Date

4.2.4. Tensions within Consumer Interaction with “Best Before” Date

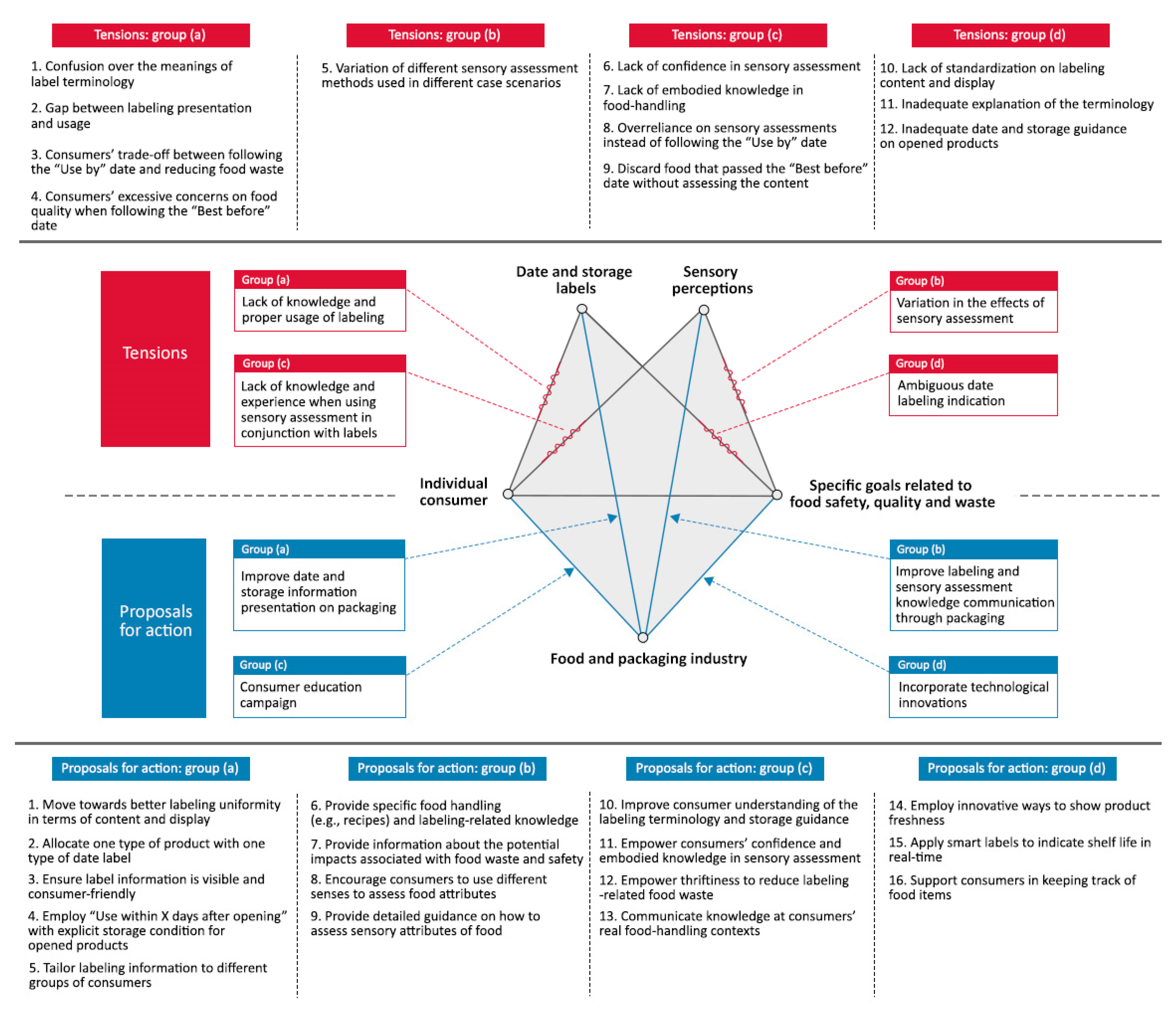

4.3. AT-based Conceptual Model of Tensions and Proposals for Actions in Food Edibility Assessment System

5. Results of Consumer Workshops and Industry Practitioner Interviews

5.1. Improved Date and Storage Information Presentation on Packaging

5.2. Improved Labeling and Sensory Assessment Knowledge Communication through Packaging

5.3. Incorporate Technological Innovations

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Design Implications

6.3. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Perspective | Aim and Research Question | Research Methodology: Qualitative or Quantitative-Based | Sample Size and Region | Product Category | Key Results Regarding the Role that Date and Storage Labeling Plays | Proposed Suggestions and Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thompson et al., 2018 [57] | Consumer food waste | The relationship between product type, date type, reduced labels and willingness to consume dairy products in relation to the both the “Best before” and “Use by” dates | Online survey, statistical analysis | 548 Scottish consumers | Dairy products | The effect on food waste reduction of moving more dairy products to the “Best before” dates is likely to be small. | Communication will need to go beyond just providing knowledge information that it is safe to eat products beyond the “Best before” date. Addressing consumer risk perceptions and label trust issues is also of the same importance. |

| Wilson et al., 2018 [56] | Consumer interpretations of labels and food waste | Consumers’ perceptions of “Best by” and “Use by” between different food items across different attributes | Experimental auctions and survey, statistical analysis | 206 participants in the US | Spaghetti sauce and deli meat | Consumers seem to associate the “Best by” dates less with safety than taste or quality. However, some consumers may still waste edible products with the “Best by” dates as the product approaches the date, even for shelf-stable products. | Information campaigns will be necessary to help consumers understand and use date labels. |

| Roe et al., 2018 [58] | Consumer food waste | Understanding how consumers react to the presence and absence of date labels on milk | Laboratory experiment, statistical analysis | 88 participants in the US | Milk | Simply removing date labels may not achieve large reductions in milk discards, as the absence of a date label appears to induce significantly more discards of in-date milk. | Empower consumers to better rely upon their senses when evaluating products like milk by introducing innovative date labeling or enhanced education about date labels. |

| Toma et al., 2017 [8] | Consumer food waste | Analyze the impact that the level of understanding of date labeling (among other influences) has on the food waste behavior of consumers | Data extracted from the Eurobarometer Survey, statistical analysis | Citizens in the 28 member states of the European Union with an average sample size of 950 | General food product | Socio-demographics, date label understanding, need for clearer date labeling information and frequency of date label checking have significant effects on reducing food waste. | Need for clearer information about date marking as consumers have become less knowledgeable of the characteristics associated with food safety and quality and rely increasingly on food label instructions. |

| Hall-Phillips and Shah, 2017 [19] | Consumer interpretations of labels | The role of unclarity, confusion surrounding expiration dates on the consumers’ path to purchasing grocery products | Semi-structured interview, thematic analysis | 19 participants in the US | Grocery products | Consumer confusion over expiration dates is caused by not only their lack of understanding of date labels, but also the consistency and the various formats and displays of labels. | 1) Consumers need education on food safety information and freshness characteristics that will enable proper handling and safe food storage at the consumers’ end; 2) Manufacturers can provide better and clearer label formats across brands and/or products. Including more consumer-friendly information on food packages, such as consistent expiration date labels that can provide consumers with additional product freshness and/or quality information. |

| Wilson et al., 2017 [55] | Consumer food waste | How date labels influence their willingness-to-waste (WTW) | Laboratory experiment, statistical analysis | 200 participants in the US | Ready-to-eat cereal, salad greens and yogurt | Consumers’ WTW is highest in the “Use by” date which suggests food safety, and lower in labels which suggest food quality. | Did not indicate explicit suggestions. |

| Van Boxstael et al., 2014 [68] | Consumer interpretations of labels and food edibility assessment | Belgian consumers’ understanding and attitude towards shelf life labels and dates | Online survey, statistical analysis | 907 Belgian consumers | General food product | 1) Most of the consumers interpret shelf life labels and dates with variation depending upon the type of food product under consideration. 2) Judging edibility of food products at home occurs mainly by a combination of checking visually and smelling, followed by looking at the shelf life date or tasting. | An increase in the understanding of date labels by consumers is needed. |

| Hebrok and Heidenstrøm, 2019 [14] | Consumer food waste | Identify decisive moments and contexts for food waste prevention and discuss examples of measures that could be further explored | Fieldwork, qualitative coding | 26 households in Norway | General food product | Consumer food assessment is in a dynamic negotiation process between institutionalized knowledge of date labels and embodied knowledge of food sensory evaluations with past experience. | 1) Use alternative ways to indicate shelf life and support consumers’ own assessments and avoid insecurities; 2) Knowledge and awarenesscampaigns on the meaning of date labeling are insufficient in achieving food waste reduction, communicating knowledge at the decisive food-handling moments is more effective. |

| Dickinson et al., 2014 [61] | Consumer food safety | To examine what actually happens in domestic kitchens in older people’s homes to assess whether and how food safety issues are caused | Ethnographic approach, qualitative analysis | 10 households with older people (aged 60+) in the UK | General food product | The lack of trust in the food supply, use of food labeling, sensory logics and food waste concerns were potential factors that influence risk of foodborne illness in older people. | Did not indicate explicit suggestions. |

| Lenhart et al., 2008 [62] | Consumer interpretations of labels and consumer food safety | To better understand consumers’ opinions about various date and food safety labeling statements among the selected high-risk population groups | Focus group discussion, qualitative coding | 85 senior aged women and women of childbearing age in the US | Refrigerated ready-to-eat (RTE) meat and poultry products | 1) From a food safety perspective, “Use by” statements were considered clearer and more helpful than “Sell by” or “Best if used by” labels by the participants; 2) Labels giving consumers instructions on how long they could keep RTE products and when to discard them after opening were considered helpful. | 1) A strong need for consumer education on guidelines for safe storage of opened packages of RTE meat and poultry products; 2) Participants wanted to receive the information through point-of-purchase pamphlets located near the deli case and through mass media venues; 3) Manufacturers are encouraged to provide more complete information on the safe storage and use of RTE meat and poultry products on package labels. |

| Samotyja, 2015 [69] | Consumer food edibility assessment | To assess how shelf-life labeling affects the sensory acceptability of potato snacks | Laboratory testing, chemical analyses, statistical analysis | 110 students in Poland | Potato snacks | Consumers are more cautious when they have no dating information or they notice deteriorative changes; they are willing to trust their own senses more than the labeling. | Date legislation is necessary but it may be insufficient without consumer education. |

| Abeliotis et al., 2016 [23] | Consumer interpretations of labels and consumer food waste | To identify the extent of engagement in nine different everyday consumer behaviors suggested by WRAP and of the effect of the Greek households’ characteristics towards food waste prevention | Questionnaire, statistical analysis | 231 shoppers in Greece | General food product | The reported consumer knowledge of food date labels indicates that there is plenty of room for education of the consumers regarding the proper meaning of the two food date labels. | The consumer knowledge on the “Expiration date” and “Best used before” food labels should be improved. |

| Daelman et al., 2013 [63] | Consumer food safety | To assess the consumption frequency, storage time, reheating practices and perception of and respect for the product’s “Use by” date | Questionnaire, statistical analysis | 874 respondents in Belgium | Refrigerated and Processed Foods of Extended Durability (REPFEDs) | Only half of the consumers fully respected the “Use by” date as indicated on the packaging of REPFED products. The majority of the remaining consumers would consume the product until three days past the “Use by” date. | Did not indicate explicit suggestions. |

| Yngfalk, 2016 [39] | Consumer food edibility assessment and food waste | The potential that date labeling holds for constructing and shaping consumers’ food consumption and disposal behavior | Interviews in the practice of meals, qualitative discourse analysis | Did not present in the paper | General food product | Date labeling largely constrains the ability of consumers to sense food by imposing an externally generated form of expert knowledge rather than an embodied sensory knowledge, thus is responsible for growing food waste. | Did not indicate explicit suggestions. |

| Wikström et al., 2014 [21] | Consumer food waste | To highlight packaging attributes that influence food waste, and present a method to illustrate how food waste may be integrated into future packaging LCAs. | Life cycle assessment (LCA) | 6 packaging formats | Rice and yogurt | Consumers are interested in packaging that gives clear messages about shelf life and storage method. However, consumers are not using the actual information that is already on the packaging. | 1) Packaging has the advantage of providing specific information on the particular item just when it is needed. For example, information about the dating system, if and when the food item could be unhealthy, and how the consumer could judge the quality of the food item. 2) Use smart labels to indicate when the food item is safe/of high quality. |

| Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2016 [60] | Food marketer and retailer in reducing consumer food waste | To identify causes and potential for actions against consumer food waste from the perspective of food marketing and retailers | A literature review, an expert interview study and case study analysis | 11 experts | General food product | 1) Food marketing and retailing contribute to consumer-related food waste via decisions on date labeling, product shelf life and package design elements that impact storage; 2) Food marketing and retailer communication on quality characteristics may also have heightened safety and health concerns or freshness orientation beyond consumers’ factual need. | Food marketers and retailers need to better design on-pack date and storage information to improve consumers’ capabilities to handle food and solve tradeoffs between food waste avoidance and other food consumption goals. |

| Ceuppens et al., 2016 [66] | Food retailer in consumer food safety | To investigate the use and consistency in date labels (i.e., “Use by” and “Best before”) and storage instructions | Snapshot of products, stakeholder survey, lab testing, statistical analysis and qualitative analysis | 4 supermarket chains in Belgium | Pre-packed refrigerated food products (n=1477) | A mixed use of the “Use by” and “Best before” dates and recommended storage conditions within a refrigerated food product category confuses consumers and thus leads to food waste and safety issues. | 1) To allocate to one food category one type of date label, which would ensure clarity to the producer/retailer and avoid confusion with consumers on how to handle these food products; 2) To keep a balance between food safety and waste concerns when setting date labels. |

| Milne, 2012 [9] | Date labeling regulation | How reforms to date marking have occurred in response to consumers’ shifting concerns about food quality, safety and latterly waste | A review of date labeling regulations in history | UK | General food product | Date labeling systems reflect societal anxieties about the food system and incorporate the changing role of consumers—from concerned housewives to neo-liberal agents of food safety to environmentally responsible actors. | Did not indicate explicit suggestions. |

| Ransom, 2005 [67] | Date labeling regulation | To provide scientific evidence for establishing Safety-Based Consume-By Date Labels (SBDL) for Refrigerated Ready-to-Eat Foods | Scientific review | US | Ready-to-Eat (RTE) Food | The use of appropriate safety-based consume-by date labels could have a beneficial public health impact for reducing foodborne illness. | The application of SBDL may need to be combined with an effective educational program for temperature control at the consumer level to reach a positive impact on public health. |

| Newsome et al., 2014 [24] | Date labeling regulation | A comprehensive review of the issue of food product date labeling | Literature review | US and international framework | General food product | The variation in date labeling terms and uses contributes to substantial misunderstandings by industry and consumers and leads to significant unnecessary food loss and waste and potential food safety risk in regards to food. | 1) Collaborate to move towards uniformity in date labeling and storage instructions; 2) Apply consumer education solutions and develop technologies at the household level to help consumers understand date information. |

| Corradini, 2018 [34] | Consumer food edibility assessment | To summarizes the necessary steps to attain a transition from open labeling to real-time shelf-life measurements | Literature review | Did not explicitly indicate | General food product | The static date labels do not take into consideration conditions that might shorten a product’s shelf life (such as temperature abuse), which can lead to problems associated with food safety and waste. | Novel analytical tools to determine safety and quality attributes with modern tracking technologies and appropriate predictive tools have the potential to provide accurate estimations of the remaining shelf life of a food product in real time. |

| Williams et al., 2012 [22] | Consumer food waste | To explore how and to what extent packaging influences the amount of food waste in the household | Diary method, quantitative analysis | 61 households in Sweden | General food product | Food that passed the “Best before” date plays a significant role in packaging-related food waste. The environmentally educated households wasted less food due to passed “Best before” dates. | Packaging is a potential information carrier that can be used to inform and explain how the consumer can use the “Best before” date, for example by explaining that it is safe to taste the content and judge if it is good. |

| Woolley et al., 2016 [33] | Food manufacturers and retailers in reducing consumer food waste | How the prevention of food waste can be facilitated by using the concept of industrial inventory management in consumer food items management | Survey, statistical analysis | 10 participants in the UK | High weight, cost, environmental impact products (e.g., animal products) | By recording and transferring data regarding product “Use by” dates to consumers’ mobile devices, it can enable consumers to better monitor food items and consume the product before its expiry date is reached. | Opportunities for the manufacturing industry to assist consumers in reducing food waste by developing tools prevalent in the industry for the domestic environment. |

| Watson and Meah, 2012 [59] | Consumer food waste and food safety | Understand how participants negotiate the “Use by” dates and what kinds of interventions should be introduced to reduce food waste | Focus groups, life-history interviews and observations, qualitative analysis | Did not present | General food products | 1) Date labels tend to redistribute responsibility away from consumers’ own sensory assessments; 2) What pulls people away from following the “Use by” date is the tension between institutionalized knowledge of date labels and antipathy towards food waste. | Information campaigns emphasizing issues of environmental responsibility have limited potential for reducing food waste. A different focus for interventions is to enable people to enact thriftiness. |

| Labuza et al., 2008 [27] | Consumer interpretations of labels and food safety | To better understand consumers’ perceptions regarding the proper handling and storage of refrigerated foods | Survey, statistical analysis | 101 consumers in the US | Refrigerated foods products | 1) Consumer confusion regarding the meaning of open dates continues; 2) Many consumers in the study are lacking in basic food safety handling skills. | 1) A federally regulated uniform open dating system is necessary to make the practice more consistent and consumer friendly; 2) Open dating used in conjunction with TTIs can inform consumers of the remaining shelf life and proper temperature conditions for storage. |

| Wansink and Wright, 2006 [64] | Consumer food safety | How “Fresh if used by” dating influences consumers’ acceptability and taste perceptions. | Taste experiment, statistical analysis | 36 consumers in the US | Yogurt | Freshness dating (i.e., “Best if used by”) influences perceptions of freshness and healthfulness, not of safety. | An important warning to companies is that as a food approaches its “freshness date”, there may be more to lose than to gain from using the “freshness dating.” Efforts to use freshness dating to connote safety or risk would be misdirected. |

| Terpstra et al., 2005 [65] | Consumer food edibility assessment and food safety | To examine consumer behavior and knowledge concerning food storage and disposal | Interviews and observations, qualitative analysis | 33 consumers in the Netherlands | Meat, vegetables, fruit juices, leftovers, cheese, dairy products | 1) Different socio-demographical groups deal with on-pack instructions differently; 2) Sensory assessments on product features are useful as indications of food quality, but they are not a reliable indication of food safety. | Consumer education about food safety, in particular food storage and food handling, is recommended. |

References

- European Commission Stop food Waste | Food Safety. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/food_waste/stop_en (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Hebrok, M.; Boks, C. Household food waste: Drivers and potential intervention points for design—An extensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohner, B.; Pauer, E.; Heinrich, V.; Tacker, M. Packaging-Related Food Losses and Waste: An Overview of Drivers and Issues. Sustainability 2019, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wikström, F.; Williams, H.; Trischler, J.; Rowe, Z. The Importance of Packaging Functions for Food Waste of Different Products in Households. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wikström, F.; Williams, H.; Venkatesh, G. The influence of packaging attributes on recycling and food waste behaviour—An environmental comparison of two packaging alternatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wikström, F.; Verghese, K.; Auras, R.; Olsson, A.; Williams, H.; Wever, R.; Grönman, K.; Kvalvåg Pettersen, M.; Møller, H.; Soukka, R. Packaging Strategies That Save Food: A Research Agenda for 2030. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, L.; Font, M.C.; Thompson, B. Impact of consumers’ understanding of date labelling on food waste behaviour. Oper. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milne, R. Arbiters of Waste: Date Labels, the Consumer and Knowing Good, Safe Food. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 60, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Food Information to Consumers—Legislation | Food Safety. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/labelling_nutrition/labelling_legislation_en (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- Himmelsbach, E.; Allen, A.; Mark, F. Study on the Impact of Food Information on Consumers’ Decision Making; TSN European Behaviour Studies Consortium: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lyndhurst, B. Consumer Insight: Date Labels and Storage Guidance; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2011; ISBN 9781844054671. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Flash Eurobarometer 425: Food Waste and Date Marking; Directorate-General for Communication (DG COMM): Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hebrok, M.; Heidenstrøm, N. Contextualising food waste prevention - Decisive moments within everyday practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; De Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-Related Food Waste: Causes and Potential for Action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NSW EPA. Love Food, Hate Waste - NSW Food Waste Tracking Survey 2015–2016; New South Wales Government: Sydney, Australia, 2016.

- Lyndhurst, B. Research into Consumer Behaviour in Relation to Food Dates and Portion Sizes; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Soethoudt, J.M.; Van der Sluis, A.A.; Waarts, Y.; Tromp, S. Expiry Dates: A Waste of Time? Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_lib_report_2013_date-marking-and-food-waste_nl-en.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Hall-Phillips, A.; Shah, P. Unclarity confusion and expiration date labels in the United States: A consumer perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leib, E.B.; Gunders, D.; Ferro, J.; Nielsen, A.; Nosek, G.; Qu, J. The Dating Game: How Confusing Food Date Labels; National Resources Defense Council: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wikström, F.; Williams, H.; Verghese, K.; Clune, S. The influence of packaging attributes on consumer behaviour in food-packaging life cycle assessment studies - a neglected topic. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Otterbring, T.; Löfgren, M.; Gustafsson, A. Reasons for household food waste with special attention to packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K.; Chroni, C. Food waste prevention in Athens, Greece: The effect of family characteristics. Waste Manag. Res. 2016, 34, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsome, R.; Balestrini, C.G.; Baum, M.D.; Corby, J.; Fisher, W.; Goodburn, K.; Labuza, T.P.; Prince, G.; Thesmar, H.S.; Yiannas, F. Applications and Perceptions of Date Labeling of Food. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 745–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manzocco, L.; Alongi, M.; Sillani, S.; Nicoli, M.C. Technological and Consumer Strategies to Tackle Food Wasting. Food Eng. Rev. 2016, 8, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ReFED. A Roadmap to Reduce U.S. Food Waste by 20 Percent, 2016. Available online: https://www.refed.com/downloads/ReFED_Report_2016.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Labuza, T.P.; Szybist, L.M.; Peck, J. Perishable Refrigerated Products and Home Practices Survey. In Open Dating of Foods; Food & Nutrition Press, Inc.: Trumbull, CT, USA, 2008; pp. 71–102. [Google Scholar]

- Leib, E.B.; Schklair, A.; Greenberg, S. Consumer Perceptions of Date Labels: National Survey. Safety 2016, 23, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Standardized Date Labeling: ReFED | Rethink Food Waste. Available online: https://www.refed.com/solutions/standardized-date-labeling (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- WRAP Food Date Labelling | WRAP UK. Available online: https://www.wrap.org.uk/food-date-labelling (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- DEFRA. Guidance on the Application of Date Labels to Food, 2011. Available online: https://www.reading.ac.uk/foodlaw/label/dates-defra-guidance-2011.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable food consumption: An overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, E.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Tseng, R.; Rahimifard, S. Manufacturing Resilience Via Inventory Management for Domestic Food Waste. Procedia CIRP 2016, 40, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corradini, M.G. Shelf Life of Food Products: From Open Labeling to Real-Time Measurements. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.; Sharp, V.; Darnton, A.; Downing, P.; Strange, K.; Inman, A.; Garnett, T. Food Synthesis Review: A Report to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; DEFRA: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leont’ev, A.N. The Problem of Activity in Psychology. Sov. Psychol. 1974, 13, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leont’ev, A.N. Activity, Consciousness, and Personality; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1978; pp. 45–74. ISBN 9780130035332. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptelinin, V.; Nardi, B.A.; Macaulay, C. Methods & tools: The activity checklist: A tool for representing the “space” of context. Interactions 1999, 6, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yngfalk, C. The milk in the sink: Waste, date labelling and food disposal. In The Practice of the Meal: Food, Families and the Market Place; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 197–207. ISBN 9781315745558. [Google Scholar]

- Glad, W. The design of energy efficient everyday practices. In eceee 2015 Summer Study on Energy Efficiency; European Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ECEEE): Stockholm, Sweden, 2015; pp. 1611–1619. [Google Scholar]

- Rexfelt, O.; Rosenblad, E. The progress of user requirements through a software development project. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2006, 36, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvefors, A.; Karlsson, I.C.M.; Rahe, U. Conflicts in Everyday Life: The Influence of Competing Goals on Domestic Energy Conservation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5963–5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woll, A.; Bratteteig, T. Activity Theory as a Framework to Analyze Technology-Mediated Elderly Care. Mind Cult. Act. 2018, 25, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Steenstra, P.; Glad, W.; Wever, R. Understanding context change: An activity theoretical analysis of exchange students’ food consumption. In Proceedings of the NordDesign: Design in the Era of Digitalization, NordDesign 2018, Linköping, Sweden, 14–17 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Engeström, Y. Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781139814744. [Google Scholar]

- Verghese, K.; Lewis, H.; Lockrey, S.; Williams, H. Packaging’s Role in Minimizing Food Loss and Waste Across the Supply Chain. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2015, 28, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimmerman, J.; Stolterman, E.; Forlizzi, J. An analysis and critique of research through design: Towards a formalization of a research approach. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, DIS 2010, Aarhus, Denmark, 18–20 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, J.; Forlizzi, J.; Evenson, S. Research through design as a method for interaction design research in HCI. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—CHI ’07; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 493–502. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; EBSE Technical Report Nr. EBSE-2007-01; Keele University: Newcastle, UK; Durham University: Durham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, O.P.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Bailey, J.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering—A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2009, 51, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews; Keele University: Newcastle, UK; Durham University: Durham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clemmensen, T.; Kaptelinin, V.; Nardi, B. Making HCI theory work: An analysis of the use of activity theory in HCI research. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 35, 608–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, N.L.; Rickard, B.J.; Saputo, R.; Ho, S.-T. Food waste: The role of date labels, package size, and product category. Food Qual. Preference 2017, 55, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, N.L.W.; Miao, R.; Weis, C. Seeing Is Not Believing: Perceptions of Date Labels over Food and Attributes. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Toma, L.; Barnes, A.P.; Revoredo-Giha, C. The effect of date labels on willingness to consume dairy products: Implications for food waste reduction. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, B.E.; Phinney, D.M.; Simons, C.T.; Badiger, A.S.; Bender, K.E.; Heldman, D.R. Discard intentions are lower for milk presented in containers without date labels. Food Qual. Preference 2018, 66, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Meah, A. Food, Waste and Safety: Negotiating Conflicting Social Anxieties into the Practices of Domestic Provisioning. Soc. Rev. 2012, 60, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; De Hooge, I.; Normann, A. Consumer-Related Food Waste: Role of Food Marketing and Retailers and Potential for Action. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2016, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, A.; Wills, W.; Meah, A.; Short, F. Food safety and older people: The Kitchen Life study. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2014, 19, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenhart, J.; Kendall, P.; Medeiros, L.; Doorn, J.; Schroeder, M.; Sofos, J. Consumer Assessment of Safety and Date Labeling Statements on Ready-to-Eat Meat and Poultry Products Designed to Minimize Risk of Listeriosis. J. Food Prot. 2008, 71, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daelman, J.; Jacxsens, L.; Membré, J.-M.; Sas, B.; Devlieghere, F.; Uyttendaele, M. Behaviour of Belgian consumers, related to the consumption, storage and preparation of cooked chilled foods. Food Control 2013, 34, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Wright, A.O. “Best if Used By…” How Freshness Dating Influences Food Acceptance. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, S354–S357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpstra, M.; Steenbekkers, L.; De Maertelaere, N.; Nijhuis, S. Food storage and disposal: Consumer practices and knowledge. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceuppens, S.; Van Boxstael, S.; Westyn, A.; Devlieghere, F.; Uyttendaele, M. The heterogeneity in the type of shelf life label and storage instructions on refrigerated foods in supermarkets in Belgium and illustration of its impact on assessing the Listeria monocytogenes threshold level of 100 CFU/g. Food Control 2016, 59, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, G. Considerations for establishing safety-based consume-by date labels for refrigerated ready-to-eat foods. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Van Boxstael, S.; Devlieghere, F.; Berkvens, D.; Vermeulen, A.; Uyttendaele, M. Understanding and attitude regarding the shelf life labels and dates on pre-packed food products by Belgian consumers. Food Control 2014, 37, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samotyja, U. Influence of shelf life labelling on the sensory acceptability of potato snacks. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Preparatory Study on Food Waste Across Eu 27; Report for the European Commission [DG ENV—Directorate C]: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; ISBN 9789279221385. [Google Scholar]

- Sonigo, P.; Bain, J.; Tan, A.; Mudgal, S.; Murphy-Bokern, D.; Shields, L.; Aiking, H.; Verburg, P.H.; Erb, K.H.; Kastner, T. Assessment of Resource Efficiency in the Food Cycle; Final Report, Prepared for European Commission (DG ENV) in Collaboration with AEA, Dr Donal Murphy-Bokern, Institute of Social Ecology Vienna and Institute for Environmental Studies; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Waarts, Y.; Eppink, M.; Oosterkamp, E.; Hiller, S.; Sluis, A.; van der Timmermans, T. Reducing Food Waste; Obstacles Experienced in Legislation and Regulations; LEI, Part of Wageningen UR: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 9789086155385. [Google Scholar]

- Brook Lyndhurst and ESA. Helping Consumers Reduce Food Waste—A Retail Survey; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Plumb, A.; Downing, P.; Parry, A. Consumer Attitudes to Food Waste and Food Packaging; Waste & Resources Action Programme: Barbury, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781844054657. [Google Scholar]

- Møller, H.; Hagtvedt, T.; Lødrup, N.; Andersen, J. Food Waste and Date Labelling: Issues Affecting the Durability; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; ISBN 9789289345569. [Google Scholar]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Ares, G.; Thøgersen, J.; Monteleone, E. A sense of sustainability?—How sensory consumer science can contribute to sustainable development of the food sector. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergönül, B. Consumer awareness and perception to food safety: A consumer analysis. Food Control 2013, 32, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unklesbay, N.; Sneed, J.; Toma, R. College students’ attitudes, practices, and knowledge of food safety. J. Food Prot. 1998, 61, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.; McCarthy, M.; Ritson, C. Why do consumers deviate from best microbiological food safety advice? An examination of ‘high-risk’ consumers on the island of Ireland. Appetite 2007, 49, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoli, M.C. An introduction to food shelf life: Definitions, basic concepts, and regulatory aspects. In Shelf Life Assessment of Food; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781439846032. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.; Downing, P. Food Behaviour Consumer Research: Quantitative Phase; Wrap: Barbury, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission “Best Before” and “Use By” Dates on Food Packaging. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_lib_best_before_en.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- European Commission Infographic on Date Marking. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_eu_actions_date_marking_infographic_en.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Kuswandi, B.; Wicaksono, Y.; Jayus, J.; Abdullah, A.; Heng, L.Y.; Ahmad, M. Smart packaging: Sensors for monitoring of food quality and safety. Sens. Instrum. Food Qual. Saf. 2011, 5, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Reinitz, H.; Simunovic, J.; Sandeep, K.; Franzon, P. Overview of RFID Technology and Its Applications in the Food Industry. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, R101–R106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collart, A.J.; Interis, M.G. Consumer Imperfect Information in the Market for Expired and Nearly Expired Foods and Implications for Reducing Food Waste. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Search Criteria | Search Terms and Criteria Applied to TITLE-ABS-KEY | Number of Records |

|---|---|---|

| Search terms used in step 2 | Group 1: (‘date labels’ OR ‘date labeling’ OR ‘shelf life label’ OR ‘food date’ OR ‘on-pack information’ OR ‘on-pack communication’ OR ‘storage guidance’) | 275 |

| Group 2: (‘food labeling’ OR ‘shelf life’ OR ‘storage information’) AND (‘food waste’ OR ‘packaging design’ OR ‘consumer behavior’) | 356 | |

| Time span of the publication | Literature published from 1960 to March 2019 | |

| Eligibility criteria used in step 3 | Step 3, inclusion (referred as S3-I1): Conference papers, journal articles and book chapters Step 3, exclusion (referred as S3-E1): Books, notes, letters, short surveys and editorials S3-E2: Papers that were not published in English | |

| Screening criteria used in step 4 | S4-I1: Papers that are related to the general theme of food labeling, consumer food assessment, food waste and food packaging design S4-E1: Papers that are irrelevant to the topic, such as studies in food bio-chemistry, food nutrients, animal science, medical science and medicine packaging design | |

| Research Focuses | Consumer Behavior Perspective | Industry Practices and Labeling Regulations Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Addressing food waste issues | Wilson et al. [55] Wilson et al. [56] Thompson et al. [57] Roe et al. [58] Toma et al. [8] Hebrok and Heidenstrøm [14] Abeliotis et al. [23] Yngfalk [39] Williams et al. [22] Watson and Meah [59] Wikström et al. [21] | Aschemann-Witzel et al. [60] Milne [9] Newsome et al. [24] Woolley et al. [33] |

| Addressing food safety issues | Dickinson et al. [61] Lenhart et al. [62] Daelman et al. [63] Watson and Meah [59] Wansink and Wright [64] Terpstra et al. [65] | Ceuppens et al. [66] Milne [9] Ransom [67] |

| Consumers’ interpretations over the meanings of date and storage labels | Wilson et al. [56] Hall-Phillips and Shah [19] Van Boxstael et al. [68] Lenhart et al. [62] Abeliotis et al. [23] Labuza et al. [27] | Newsome et al. [24] |

| Food edibility assessment methods in household contexts | Hebrok and Heidenstrøm [14] Samotyja [69] Yngfalk [39] Van Boxstael et al. [68] Terpstra et al. [65] Corradini [34] | No relevant papers (in the scope of this literature review) |

| Actions and Mediating Tools | Specific Tensions | Corresponding Behavior | Potential Outcomes | Corresponding Proposals for Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A1). Consumer perception and usage of date labels | Lack of adequate explanation of different label terminologies | Some consumers refuse to trust date labels and lack of correct understandings on different date labeling terminologies [17,25,26,27,59,61,70]. Consumers are confused over the differences between “Best before” and “Use by” dates [8,11,12,16,23,27,66,68]. | Lead to problems mainly associated with food waste | Consumer education campaigns: Education campaigns are necessary to help consumers understand different date labels [24,56,71]. Improve consumer knowledge on the “Use by” date and “best before” date [23,70,71]. |

| Lack of consistency on label content and display | Most of the consumers interpret date labels with variation depending upon the type of food product under consideration [68]. Various formats and displays of date labels create confusions when consumers need to check date information [17,19,26]. | Lead to problems mainly associated with food waste | Move towards better label uniformity: To allocate to one food category one type of date label and storage guidance to ensure uniformity [24,26,66]. Food and packaging industry practitioners need to standardize and ensure date and storage information on packaging are visible and easy to follow by consumers [12,19,27,46,70,71,72]. | |

| The gap between information presentation and usage | The percentage of consumers who use on-pack date labels as guidance for assessing food is estimated to be approximately 50% [68]. Consumers expressed the need for clear on-pack shelf life and storage information; however, they did not use the information that already existed on packaging [21,74]. | Lead to problems mainly associated with food waste | Communicate knowledge in activity contextual settings: Education and awareness campaigns are insufficient in achieving food waste reduction. Date and storage labeling need to be communicated at consumers’ real food-handling contextual setting [14]. Consumers would like to receive the meaning of date labels through point-of-purchase pamphlets, cookbooks, and restaurants [15,62]. Potential material for date label explanation includes signage, other materials at the point of sale and QR codes [24]. | |

| Packaging can be improved to provide consumers with more detailed information on shelf life and storage methods in the contextual moments when the food item is used [8,21,75]. Impacts of food waste and safety information can be presented on packaging along with date information to raise consumer awareness [25]. Incorporate new technologies to indicate shelf life: Use smart/intelligent labels to indicate whether the food item is safe or of high quality [21,28,80]. | ||||

| (B1). Consumer sensory assessment | Lack of confidence in sensory assessments | Some consumers seem to solely rely on date labels to judge food edibility, which may largely constrain their own sensory assessment abilities [17,39,59]. Consumers are insecure in using their sensory assessments for specific food products (e.g., milk), the absence of a date label on those food products appears to induce more discards of in-date food [58]. Consumers often follow the rule of thumb “when in doubt, throw it out” in their food disposal decision-making process [34]. | Lead to problems mainly associated with food waste | Improve general food-related knowledge: Empower consumer knowledge in using their sensory assessments and reduce consumers’ insecurity feelings [14,58]. Introduce packaging-related intervention: Packaging can be used to explicitly inform consumers that it is safe to taste the content or use other senses for assessments [21,22,60]. |

| Lack of knowledge in food handling | Consumers have become less knowledgeable of food attributes associated with both safety and quality [8]. Consumers are lacking in basic food safety handling skills, such as lack of temperature control for food at home [27]. | Lead to problems mainly associated with food waste | Provide general food handling knowledge guidance on packaging: Consumers need education about safe food storage and handling [19,65]. Need for clearer information about date marking on packaging since consumers have become less knowledgeable of the food attributes associated with safety and quality and rely increasingly on food label instructions [8]. Food manufacturers and retailers are encouraged to provide more information on safe storage and handling of refrigerated products on package labels [62]. | |

| (C1). Safety indicator: “Use by” date | The safety effects of the “Use by” date vary across different cases | “Use by” dates were considered by consumers as more helpful for indicating food safety than other labels [55,62,67,77,78]. Only half of the respondents tend to follow “Use by” dates indicated on refrigerated and processed products [63]. Some consumers are more concerned with food waste issues, thus eat food that has passed its “Use by” date [59,61]. Pregnant women and parents with kids read label instructions more frequently than senior people who tend to only use their own sensory perceptions to make judgments [12,65,81]. | Ensured food safety in some cases but compromised safety issues on others. | Tailor label communication to meet consumers’ particular needs: Communication will need to focus on addressing consumer risk perceptions and label trust issues [57]. Communicate date label-related knowledge to the special groups of consumers such as elderly people, pregnant women, and people who are immune-compromised, to meet their particular interests and needs [62]. Expand date label information to include guidance (e.g., recipes) that can help consumers to solve tradeoffs between food safety and waste [60]. Help consumers to better manage food items in the household: Transferring product Use-by dates to consumers’ mobile devices to remind consumers to eat the product in time [33]. |

| Inadequate date and storage guidance on opened products | Some consumers do not know that the “Use by” date ceases to apply when the product has been opened, while some discard the opened food items due to uncertainty of the remaining shelf life [65,73,75]. For refrigerated food products, label instructions about when to discard the products after opening were considered helpful by consumers [62,75]. The food industry faces the difficulty in measuring the shelf life of opened products [75,80]. | Lead to problems associated with both food safety and waste | Improve date label statement and education: Labels such as “Use within X days after opening” might be more effective if combined with education campaigns such as temperature control at home [67,73,75,80]. Consumers need education on specific guidelines such as where to store and how to assess products that have been opened [19,62,73,75]. Use smart labels to indicate shelf life: Date labels combined with time-temperature indicators (TTIs) can inform consumers the remaining shelf life in real time [27,34]. Develop technologies at the household level (e.g., mobile applications) to help consumers to better manage their food items and track the expiration date [24]. | |

| (C2). “Use by” date used in conjunction with sensory perceptions | Potential risks of overreliance on sensory assessments for food safety judgment | Some consumers regard their own sensory assessments as a more reliable way to judge food safety than the “Use by” labels [59,61,65]. Consumers tend to apply their sensory perceptions and past experience when they are familiar with the particular food products under concern [17,35,74,79]. | Lead to problems mainly associated with food safety | No results based on our literature review. |

| (D1and D2). Quality indicator: “Best before” date | Foods that reach the “Best before” date turned into food waste | Consumers waste edible products with a “Best before” date as the product is close to or passes the date [11,23,28,56,75]. Food marketing communication may have overemphasized food quality and freshens attributes rather than consumers’ actual needs [60]. The use of sensory perceptions in conjunction with “Best before” date labels is more likely to reduce the variability of household food wastage [12,17]. | Lead to problems mainly associated with food waste | Present date label-related information on packaging: Product packaging can be used to explain how to better follow the “Best before” date [8,14,21,22,58,60]. Develop on-pack label innovations which can provide consumers with additional product freshness and/or quality information [19,79]. Consumer education campaign: Enhance consumer education about how to use “Best before” date labels and their connection to food waste issues [58]. A different focus for food waste interventions is to enable people to enact thriftiness [59]. |

| Proposals for Action | Evaluation from the Consumer Side | Evaluation from the Industry Side |

|---|---|---|

| Label uniformity | More descriptive and explanatory label statements. Provide detailed storage guidance (e.g., can it be frozen). Data visualization of shelf life with the probability for bacteria to grow. | Simplification of the date labeling system to a single set of terminology. Conflicting opinions between the “Use by” date and “Best before” date. Improve readability: labels should be clear, stand out, have large fonts and be less congested. Avoid wordy and negative information. Provide detailed descriptions to guide better storage. |

| Label for opened products | A timer or sticker to show when the product was opened. Remind people the products have been opened. | “Use within X days after opening” should stand out with large fonts. Adding storage conditions right next to the “Use within X days after openning” statement. |

| Proposals for Action | Evaluation from the Consumer Side | Evaluation from the Industry Side |

|---|---|---|

| Communicate knowledge through packaging | Packaging designed to encourage people to evaluate food with different senses. Include tips for sensory assessments. Written descriptions of sensory attributes are insufficient. Images that show a comparison between edible and spoiled products. Detailed information about the ingredients that can go bad. | Avoid touching upon the legal grey area. Encourage consumers to trust their senses. Include information on how to better use food items in its different shelf life periods (e.g., recipes). Prioritizing the mandatory labels due to the space limit. |

| Proposals for Action | Evaluation from the Consumer Side | Evaluation from the Industry Side |

|---|---|---|

| Smart label/ real-time indicators | Perceived as useful especially on products that may cause food safety risks (e.g., meat) and products after opening. Use color differences to indicate the conditions of food. | Advantages: Avoid confusions between the “Best before” date and “ Use by” date; Help to detect food status (e.g., temperature abuse) through the supply chain and in the household; Assign responsibility to consumers. |

| Drawbacks: Different smart label standards can create more confusion to consumers; Add complexity to packaging recyclability; Lack of economic incentives; Take controls away from food manufacturers and retailers. | ||

| QR codes and consumer mobile devices | Simple technological solution. Avoid disrupting the existing food consumption activity routines. | Advantages: Simple and inexpensive solutions; Save room on packaging; A window for consumer interaction with product and brand; Tailored communication of a variety of information to consumers (e.g., shelf life, storage methods, environmental impacts, recipes, production). |

| Drawbacks: Effects vary across different socio-demographical groups and socio-cultural background. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, W.; Williams, H.; Verghese, K.; Wever, R.; Glad, W. Tensions and Opportunities: An Activity Theory Perspective on Date and Storage Label Design through a Literature Review and Co-Creation Sessions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031162

Chu W, Williams H, Verghese K, Wever R, Glad W. Tensions and Opportunities: An Activity Theory Perspective on Date and Storage Label Design through a Literature Review and Co-Creation Sessions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031162

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Wanjun, Helén Williams, Karli Verghese, Renee Wever, and Wiktoria Glad. 2020. "Tensions and Opportunities: An Activity Theory Perspective on Date and Storage Label Design through a Literature Review and Co-Creation Sessions" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031162

APA StyleChu, W., Williams, H., Verghese, K., Wever, R., & Glad, W. (2020). Tensions and Opportunities: An Activity Theory Perspective on Date and Storage Label Design through a Literature Review and Co-Creation Sessions. Sustainability, 12(3), 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031162