Willingness of the New Generation of Farmers to Participate in Rural Tourism: The Role of Perceived Impacts and Sense of Place

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Study Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Hierarchy of Effects Model

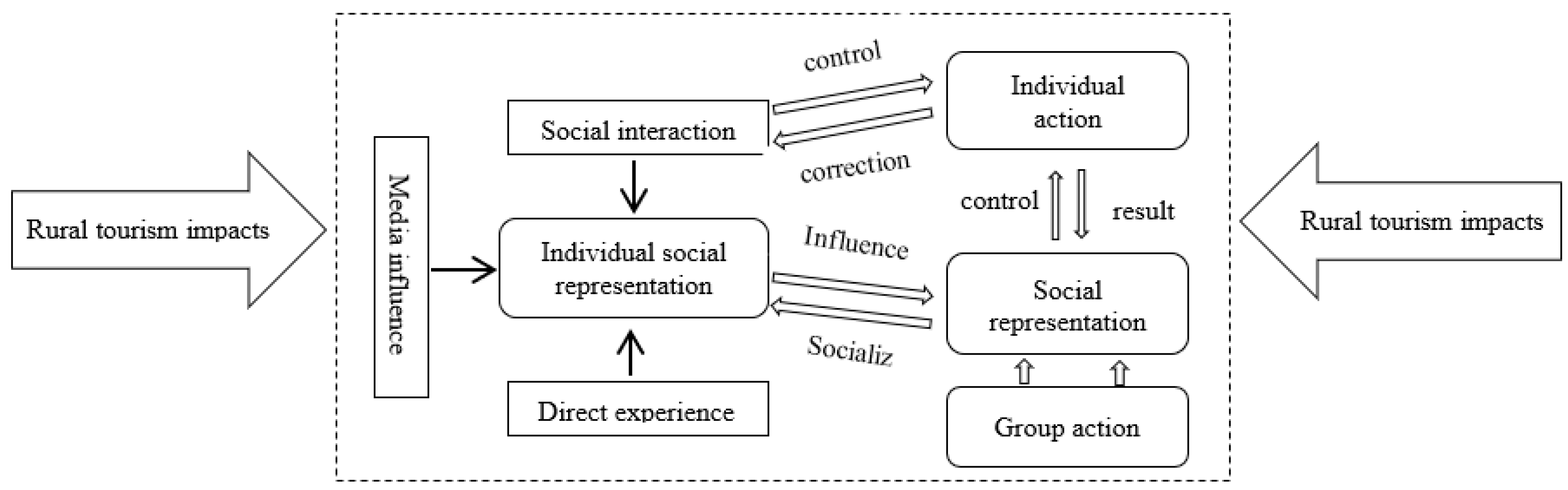

2.1.2. Social Representation Theory

2.1.3. Sense of Place

2.2. Literature Review and Study Hypothesis

2.2.1. Perceived Impacts of Rural Tourism and Residents’ Willingness to Participate

2.2.2. Perceived Impacts of Rural Tourism and Sense of Place

2.2.3. Sense of Place and Residents’ Willingness to Participate

2.2.4. Mediation Effect of Sense of Place on the Perceived Impacts of Residents’ Willingness to Participate

2.3. Structural Relation Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Area Overview

3.2. Questionnaire Design and Variable Measurement

3.3. Data Collection and Sample Overview

3.4. Methodology

3.5. Verification of Common Method Bias

3.6. Bias Reliability and Validity Analysis

4. Results

4.1. The Measurement Model

4.2. Subsection Tests of Hypotheses

4.3. Test of Mediation Effect

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Future Research

5.2. Implications for Pratice

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

Section A: Perceived Impacts of Rural Tourism

| Perceived Impacts of Rural Tourism | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I think rural tourism improves the revenue generated in the local economy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. Rural tourism develops employment opportunities in the rural community. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. Rural tourism holds great promise for a rural community’s economic future. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. It is widely believed that the development of rural tourism in rural areas has a positive effect on rural development. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. Rural tourism improves the quality of life in my hometown. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. Rural tourism development provides more recreational opportunities for locals. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7. Rural tourism improves the image of rural areas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8. Rural tourism provides more parks and other recreational areas for local residents. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9. Rural tourism improves the appearance (and images) of a rural community’s landscape. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10. I think rural tourism improves the living environment. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Section B: Sense of Place

| Sense of Place | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11. I feel my hometown is a part of me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12. My hometown is very special to me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13. I have a special connection to the people who live in my hometown. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 14. Staying here makes me forget my problems. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 15. Many of my friends/family prefer their hometown over other communities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 16. I respect what my hometown stands for. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Section C: Willingness to Participate in Rural Tourism Development

| Willingness to Participate in Rural Tourism Development | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17. I plan to participate or invest in the development of rural tourism. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 18. I would like to recommend others to participate or invest in rural tourism operation. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 19. I will relay the positive message of rural tourism to others. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Section D: Personal and Family Status

- 20

- What is your gender?☐ Male ☐ Female

- 21

- What is your nation?☐ Han nationality ☐ Minority

- 22

- How old are you?☐ Less than 20 ☐ 20–25 ☐ 26–30 ☐ 31–35 ☐ 36–39

- 23

- What is your maximum education level reached?☐ Less than junior high school☐ Junior high school☐ High school graduate☐ Some college☐ Graduate student

- 24

- Do your relatives or friends participate in rural tourism? (This option allowed for multiple selections.)☐ I engaged or invested in☐ My parents or relatives engaged or invested in☐ My friends engaged or invested in☐ My relatives and friends are employed by rural tourism enterprises☐ None of them are involved

- 25

- What is your family’s annual income?☐ Less than 50,000 Yuan☐ 50,000–100,000 Yuan☐ 100,001–200,000 Yuan☐ 200,001–300,000 Yuan☐ 300,000 Yuan or more

- 26

- How long have you lived in rural area?☐ 1–6 years ☐ 7–12 years ☐ 13–18 years ☐ 19–25 years ☐ always

- 27

- What is your current employment status?☐ Part time ☐ Full time ☐ Self-employed ☐ Not currently employment

References

- Gao, J.; Wu, B.H. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, G.; Clark, G.; Oliver, T.; Ilbery, B. Conceptualizing Integrated Rural Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.S.; Figueiredo, E.; Eusebio, C.; Carneiro, M.J. The countryside is worth a thousand words—Portuguese representations on rural areas. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesala, H.T.; Vesala, K.M. Entrepreneurs and producers: Identities of Finnish farmers in 2001 and 2006. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, P. Young adults’ perceptions of and affective bonds to a rural tourism community. Fenn. Inter. J. Geog. 2016, 194, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-García, F.; Peláez-Fernández, M.A.; Balbuena-Vázquez, A.; Macias, R. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, N.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ support for tourism: An Identity Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, F.A.; Vazquez, A.B.; Macias, R.C. Resident’s attitudes towards the impacts of tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Croes, R.; Lee, S.H. Tourism development and happiness: A residents’ perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.M.; Zhao, L. Influence of perceived value on the willingness of residents to participate in the construction of a tourism town: Taking Zhejiang Moganshan tourism town as an example. Tour. Trib. 2019, 34, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. The Role of Place Image Dimensions in Residents’ Support for Tourism Development. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; Chen, J.M.; Yang, X.J. The Impact of Advertising Creativity on the Hierarchy of Effects. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.; Brawley, L.; Craig, C.; Plotnikoff, R.; Tremblay, M.; Bauman, A.; Faulkner, G.; Chad, K.; Clark, M. Participation: Awareness of the Participation campaign among Canadian adults—Examining the knowledge gap hypothesis and a hierarchy-of-effects model. Int. J. Behave. Nutr. Phy. Acti. 2009, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiotsou, R.H. Sport team loyalty: Integrating relationship marketing and a hierarchy of effects. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanapragash, T.J.; Sekar, P.C. Celebrity-aided brand recall and brand-aided celebrity recall: An assessment of celebrity influence using the hierarchy of effects model. IUP J. Brand Manag. 2013, 10, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtar, A. A framework for Islamic advertising: Using Lavidge and Steiner’s hierarchy of effects model. Intell. Disco. 2016, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Yang, X.H.; Yang, Y.F. Importance conveyed in different ways: Effects of hierarchy and focus. J. Neurolinguist. 2018, 47, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Samiei, N.; Dini, B.; Manzari, P.Y. Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: An integrated approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P. Customer loyalty: Exploring its antecedents from a green marketing perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag 2015, 27, 896–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Quintal, V.A.; Phau, I. Wine Tourist Engagement with the Winescape: Scale Development and Validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 793–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rateau, P.; Moliner, P.; Guimelli, C.; Abric, J.C. Social representation theory. Handb. Theor. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 2, 477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, P.L.; Moscardo, G.; Ross, G.F. Tourism Community Relationship; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, T.Y. Several Issues on the Application of Social Representation Theory in Tourism Research. Tour. Trib. 2004, 19, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values, Morningside ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; p. xiv, 260. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the Commodity Metaphor—Examining Emotional and Symbolic Attachment to Place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M. The City and Self-Identity. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D. People in places: A transactional view of settings. Cogn. Soc. Behav. Environ. 1981, 1, 441–488. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners’ attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, R.; Gajić, T.; Bugar, D. Tourism as a basis for development of the economy of Serbia. UTMS J. Econ. 2012, 3, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, C. Assessing the sustainability of agritourism in the US: A comparison between agritourism and other farm entrepreneurial ventures. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H. The impacts of tourism and local residents’ support on tourism development: A case study of the rural community of Jeongseon, Gangwon Province, South Korea. Au-Gsb E-J. 2013, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, D.G. Community Participation in Tourism Planning. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Plaza-Mejia, M.Á.; Porras-Bueno, N. Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in a former mining community. J. Travel Res. 2009, 47, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L. Tourism impacts and support for tourism development in Ha Long Bay, Vietnam: An examination of residents’ perceptions. Asia Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ap, J. Residents Perceptions on Tourism Impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandth, B.; Haugen, M.S. Farm diversification into tourism—Implications for social identity? J. Rural. Stud. 2011, 27, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, S.H.; Pettersson, K. Performing gender and rurality in Swedish farm tourism. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Kerstetter, D.; Hunt, C. Tourism development and changing rural identity in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, P.T.; Perdue, R.R.; Allen, L. Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes by community level of tourism. J. Travel. Res. 1990, 28, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ramayah, T. Urban vs. rural destinations: Residents’ perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, P.C. Resident attitudes toward heritage tourism development. Tour. Geog. 2010, 12, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G.; Gursoy, D.; Vieregge, M. Residents’ perceptions toward tourism development: A factor-cluster approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Segota, T.; Mihalic, T.; Kuscer, K. The impact of residents’ informedness and involvement on their perceptions of tourism impacts: The case of Bled. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 196–206. [Google Scholar]

- Demurger, S.; Xu, H. Return Migrants: The Rise of New Entrepreneurs in Rural China. World. Dev. 2011, 39, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. Return Migration and Regional Economic Development: An Overview; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of Tourists’ Loyalty to Mauritius: The Role and Influence of Destination Image, Place Attachment, Personal Involvement, and Satisfaction. J. Travel. Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.B.; Su, Q. Study on the Relationship between the Community Participation of Rural Tourism, Residents’ Perceived Tourism Impact and Sense of Community Involvement—A Case Study of Anji Rural Tourism Destination, Zhejiang Province. Tour. Trib. 2011, 26, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahzadeh, G.; Sharifzadeh, A. Rural Residents’ Perceptions toward Tourism Development: A Study from Iran. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Y. Influence model and mechanism of the rural residents for tourism support: A comparison of rural destinations of Suzhou in different life cycle stages. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2011, 66, 1413–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Wei, Z.; Wang, L. Residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development in a historical-cultural village: Influence of perceived impacts, sense of place and tourism development potential. Sustainability 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.H.; Wu, J.L.; Xiong, J. Structural relationship of residents’ perception of tourism impacts: A case study in world natural heritage Mount Sanqingshan. Prog. Geog. 2014, 33, 584–592. [Google Scholar]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Stedman, R.; Luloff, A.E. Permanent and seasonal residents’ community attachment in natural amenity-rich areas: Exploring the contribution of landscape-related factors. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Place attachment and public acceptance of renewable energy: A tidal energy case study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Brown, G.; Lindsay, N.J. The Place Identity—Performance relationship among tourism entrepreneurs: A structural equation modelling analysis. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujang, N.; Zakariya, K. Place Attachment and the Value of Place in the Life of the Users. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 168, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host attitudes toward tourism - An improved structural model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, L.N.; Thapa, B.; Ko, Y.J. Residents’ Perspectives of A World Heritage Site The Pitons Management Area, St. Lucia. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Brown, G.; Lindsay, N.J. Examining tourism SME owners’ place attachment, support for community and business performance: The role of the enlightened self-interest model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 658–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, M.; Brklacich, M. New farmers’ efforts to create a sense of place in rural communities: Insights from southern Ontario, Canada. Agri. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.; Kash, D.; Bolger, N. Data Analysis in Social Psychology. Handb. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 1, 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.L.; Graefe, A.R. Attachments to Recreation Settings—the Case of Rail-Trail Users. Leis. Sci. 1994, 16, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, H. Relationship between the place attachment of ancient village residents and their attitude towards resource protection a case study of Xidi, Hongcun and Nanping villages. Tour. Trib. 2008, 23, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin, S.; Ujang, N. Making places: The role of attachment in creating the sense of place for traditional streets in Malaysia. Habitat Int. 2008, 32, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Perkins, D. Disruptions in Place Attachment. Human Behav. Environ. 1992, 12, 279–304. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J. Placing home in context. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R. Sense of place in developmental context. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N.; Williams, D.; McHugh, K. Multiple Dwelling and Tourism: Negotiating Place, Home and Identity; CABI: Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alipour, S.; Kaboudi, M. Community Perception of Tourism Impacts and Their Participation in Tourism Planning: A Case Study of Ramsar, Iran. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 36, 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Ryan, C.; Cave, J. Chinese rural tourism development: Transition in the case of Qiyunshan, Anhui 2008–2015. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, M.; Jamaluddin, M.; Zulkifly, M. Local Community Attitude and Support towards Tourism Development in Tioman Island, Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ujang, N. Place Attachment and Continuity of Urban Place Identity. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The Relations between Natural and Civic Place Attachment and Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneafsey, M. Tourism and Place Identity: A case-study in rural Ireland. Iri. Geog. 1998, 31, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R.; Bacon, J. Effects of place attachment on users’ perceptions of social and environmental conditions in a natural setting. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigger-Ross, C.; Bonaiuto, M.; Breakwell, G. Identity theories and environmental psychology. Psychol. Theor. Environ. Issues 2003, 1, 203–234. [Google Scholar]

- Breakwell, G. Coping with threatened identities. Coping Threat. Identities 2015, 5, 1–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution—Implications for Management of Resources. Can. Geogr-Geogr. Can. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.H. On the Issue of the New Generation of Migrant Workers. Issue Agr. Ecosyst. 2010, 4, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Pan, L.; Heerink, N. Working Conditions and Job Satisfaction of China’s New Generation of Migrant Workers: Evidence from an Inland City; IZA Discussion Paper No. 7405; Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2013; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q.Y.; Mai, Q. How to Improve New Generation Migrant Workers’ Entrepreneurial Willingness-A Moderated Mediation Examination from the Sustainable Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Hamilton, J.G. Viability of Exploratory Factor Analysis as a Precursor to Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. 1996, 3, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhu, H. Influence of perceived brand globalness and environmental image on consumption intentions: A case study of H&M. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 699–710. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, G.; Sun, S. Theoretical Model and Empirical Study of Translocal Food Rebranding. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2016, 71, 338–351. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education Inc.: London, UK, 2005; p. 928. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological-Research—Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M. Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effect in Structural Equation Models. Sociol. Methodol. 1982, 13, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construction | Code | Items | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived economic impacts (PE) | PE1 | I think rural tourism improves the revenue generated in the local economy. | Rivera et al. [9]; Stylidis et al. [11]; Sinclair-Maragh [43] |

| PE2 | Rural tourism develops employment opportunities in the rural community. | ||

| PE3 | Rural tourism holds great promise for a rural community’s economic future. | ||

| PE4 | It is widely believed that the development of rural tourism in rural areas has a positive effect on rural development. | ||

| Perceived social-cultural impacts (PS) | PS1 | Rural tourism improves the quality of life in my hometown. | Almeida-García et al. [6]; Abdollahzadeh and Sharifzadeh [50]; Alipour and Kaboudi [72]; Li et al. [73] |

| PS2 | Rural tourism development provides more recreational opportunities for locals. | ||

| PS3 | Rural tourism improves the image of rural areas. | ||

| Perceived environmental impacts (PEI) | PEI1 | Rural tourism provides more parks and other recreational areas for local residents. | Šegota et al. [44]; Hanafiah et al. [74] |

| PEI2 | Rural tourism improves the appearance (and images) of a rural community’s landscape. | ||

| PEI3 | I think rural tourism improves the living environment. | ||

| Place identity (PI) | PI1 | I feel my hometown is a part of me. | Kneafsey [78]; Williams et al. [79]; Kyle et al. [80] |

| PI2 | My hometown is very special to me. | ||

| PI3 | I have a special connection to the people who live in my hometown. | ||

| Place attachment (PA) | PA1 | Staying here makes me forget my problems. | Scannell and Gifford [48]; Lee [60]; Ujang [76] |

| PA2 | Many of my friends/family prefer their hometown over other communities. | ||

| PA3 | I respect what my hometown stands for. | ||

| Residents’ willingness to participate (WTP) | W1 | I plan to participate or invest in the development of rural tourism. | Zhang and Zhao [10]; Ajzen [83]; Han and Kim [85] |

| W2 | I would like to recommend others to participate or invest in rural tourism operation. | ||

| W3 | I will relay the positive message of rural tourism to others. |

| Variables | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 117 | 44.49 |

| Female | 146 | 55.51 |

| Nationality | ||

| Han | 219 | 83.27 |

| Minority | 44 | 16.73 |

| Age | ||

| Less than 20 | 11 | 4.18 |

| 20–25 | 67 | 25.48 |

| 26–30 | 138 | 52.47 |

| 31–35 | 20 | 7.60 |

| 36–39 | 27 | 10.26 |

| Maximum education level reached | ||

| Less than junior high school | 6 | 2.28 |

| Junior high school | 17 | 6.46 |

| High school graduate | 38 | 14.45 |

| Some college | 176 | 66.92 |

| Graduate student | 25 | 9.51 |

| Family and friends involvement in rural tourism * | ||

| I engaged or invested in | 15 | 5.70 |

| My parents or relatives engaged or invested in | 23 | 8.75 |

| My friends engaged or invested in | 66 | 25.10 |

| My relatives and friends are employed by rural tourism enterprises | 103 | 39.16 |

| None of them are involved | 107 | 40.68 |

| Annual household income | ||

| Less than 50,000 Yuan | 47 | 17.87 |

| 50,000–100,000 Yuan | 70 | 26.62 |

| 100,001–200,000 Yuan | 81 | 30.80 |

| 200,001–300,000 Yuan | 33 | 12.55 |

| 300,000 Yuan or more | 32 | 12.17 |

| Length of residence in rural area | ||

| 1–6 years | 21 | 7.98 |

| 7–12 years | 19 | 7.22 |

| 13–18 years | 91 | 34.60 |

| 19–25 years | 36 | 13.69 |

| always | 96 | 36.50 |

| Employment | ||

| Part time | 26 | 9.89 |

| Full time | 182 | 69.20 |

| Self-employed | 45 | 17.11 |

| Not currently employment | 10 | 3.8 |

| Variables | AVE | CR | P | PI | PA | WTP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 0.746 | 0.898 | 0.864 | - | - | - |

| PI | 0.729 | 0.890 | 0.439 | 0.854 | - | - |

| PA | 0.620 | 0.830 | 0.365 | 0.590 | 0.788 | - |

| WTP | 0.634 | 0.837 | 0.461 | 0.355 | 0.469 | 0.797 |

| Fit Index | Absolute Fitting Index | Value-Added Fitting Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | GFI | RMSEA | NFI | CFI | IFI | |

| Suggested value | <3 | ≥0.9 | ≤0.08 | ≥0.9 | ≥0.9 | ≥0.9 |

| Observed value | 2.732 | 0.925 | 0.08 | 0.931 | 0.955 | 0.955 |

| Conclusion | Accepted | Good fit | Good fit | Good fit | Good fit | Good fit |

| Paths | Standaredised-Estimated | S.E. a | C.R. b | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (β1) | 0.350 *** | 0.096 | 4.909 | Support |

| (β2) | 0.457 *** | 0.074 | 7.257 | Support |

| (β3) | 0.392 *** | 0.068 | 5.256 | Support |

| (β4) | 0.714 *** | 0.088 | 10.232 | Support |

| Regression Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | - | 0.619 *** | - | - | 0.212 | |

| (2) | - | 0.521 *** | - | - | 0.193 | |

| (3) | - | - | 0.662 *** | - | 0.348 | |

| (4) | 0.473 *** | - | - | - | 0.220 | |

| (5) | 0.175 ** | - | 0.597 *** | - | 0.362 | |

| (6) | 0.402 *** | - | 0.137 * | - | 0.229 | |

| (7) | 0.347 *** | - | 0.00743 | 0.446 *** | 0.316 |

| Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.479 *** | 0.350 *** | 0.129 *** | Partial mediation | |

| 0.457 *** | 0.457 *** | - | No mediation | |

| 0.714 *** | 0.714 *** | - | No mediation | |

| 0.784 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.327 *** | Partial mediation | |

| 0.392 *** | 0.392 *** | - | No mediation | |

| 0.280 *** | - | 0.280 *** | Full mediation |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, B.; Mi, Z.; Zhang, Z. Willingness of the New Generation of Farmers to Participate in Rural Tourism: The Role of Perceived Impacts and Sense of Place. Sustainability 2020, 12, 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030766

Li B, Mi Z, Zhang Z. Willingness of the New Generation of Farmers to Participate in Rural Tourism: The Role of Perceived Impacts and Sense of Place. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030766

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Binbin, Zengyu Mi, and Zhenghe Zhang. 2020. "Willingness of the New Generation of Farmers to Participate in Rural Tourism: The Role of Perceived Impacts and Sense of Place" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030766

APA StyleLi, B., Mi, Z., & Zhang, Z. (2020). Willingness of the New Generation of Farmers to Participate in Rural Tourism: The Role of Perceived Impacts and Sense of Place. Sustainability, 12(3), 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030766