1. Introduction

After World War II, many growing European cities adopted the functional city concept [

1] as a preferred direction of further development and territorial expansion triggered by massive migrations to cities. Defined in the Athens Charter, a CIAM’s (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) document from 1933, this concept was based on the premise of efficient traffic resulting in a grid of high-speed primary roads outlining large blocks (super-blocks). Consisting of freestanding high-rise buildings positioned in green open spaces (approximately 48–85%), these blocks were supposed to accommodate large numbers of people on a limited territory increasing quality of life through functional efficiency and environmental comfort. Therefore, Le Corbusier emphasized the importance of their green features, treating them as apartment extensions and city lungs (Le Corbusier, 1987) [

2]. However, new blocks included only basic services, while commercial, business, and cultural activities were incorporated into so-called regional centers.

Belgrade, the capital of Yugoslavia, also increased the number of inhabitants from approximately 330,000 to 1.6 million and embraced functionalism as an appropriate framework of urbanization, perceived both as an ideological and socio-economic imperative. The construction industry flourished, reviving the national and local economy, while the quality of life also improved. The introduction of a super-block, as a basic spatial unit, was supported by new urban infrastructure, while the construction of New Belgrade, as a new administrative center of Yugoslavia, was used as a role model and a symbol of overall progress. Consequently, Le Corbusier’s ideas were applied in other urban areas, from emerging settlements to the more historic parts under reconstruction. Due to its spatial structure with large public areas accessible to all, a super-block was initially conceived as a neighborhood providing a safe and ecologically advanced environment, without internal car traffic. However, many authors have emphasized physical, functional, and social failures of this concept, which created impersonal spaces for introverted communities, reducing human interaction, and favoring cars [

3,

4,

5]. Therefore, the modernist super-blocks have become a focus of serious re-assessments. For example, the cases of eight super-blocks in four cities in Italy and Spain (Rome, Milan, Madrid, Barcelona) were analyzed in accordance to connectivity to their surroundings and their ability to overcome their imposed self-sufficiency and isolation [

6], while the lack of spatial differentiation and hierarchy in Swedish suburbs was reconsidered by the application of the space syntax method [

7]. However, the post-socialist cities had to face additional problems caused by a radical socio-economic change, which was reflected in all levels of life, including urban systems and urban form. The introduction of the land market, commercial real estate, changed legislation, and the (im)balance of power have had a significant impact on the inherited urban structure, especially affecting the open structure of super-blocks and their public spaces [

8,

9,

10]. In the post-socialist context of Serbia, characterized by the delayed transitional process during the 1990s and 2000s, the condition of super-blocks and their open areas was additionally challenged by socio-economic and political turbulences resulting in the negligence or usurpation of public spaces [

11,

12,

13]. Considering the UN-Habitat framework, and the Sustainable Development Goals, which underline the importance of local communities for urban development, their reactivation and renewal have become a necessity [

14,

15]. The participatory design has been encouraged as a method contributing to social cohesion through new and reconstructed urban forms, with increased accessibility and improved physical, cultural, and social identity of shared areas [

16].

Although the social aspect of sustainability was already mentioned in the Brundtland Report [

17] and Agenda 21 [

18], its importance has increased since the end of the 1990s, gaining the attention of researchers and policy makers. Defining and measuring social sustainability is not an easy task due to its multidisciplinary character, which interrelates society and the built environment, but various authors agree that social capital, human capital, and well-being represent its main features [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Mehan and Soflaei [

26] underline the importance of future focus, the level of satisfied needs, social cohesion, and the physical integration of urban units, while Eizenberg and Jabareen [

27] propose the Conceptual Framework of Social Sustainability, which considers the contemporary risks triggered by climate change. Based on the extensive review of literature, this theoretical framework is defined as a construct of four interrelated concepts—equity, safety, urban forms, and eco-prosumption. Using the notion of (environmental) risk as a foundation of sustainability, the concept of equity incorporates three dimensions—redistribution, recognition, and participation, while the concept of safety is described as a context-specific driver of the adaptation process defined by detected vulnerabilities. The physical aspects of social sustainability refer to the mitigation and adaptation potential of urban form, based on the imperatives of achieving a sense of community, its place attachment and health, while the eco-prosumption concept tackles the issue of social and environmental awareness and responsibility introduced through emerging measures, mechanisms, and practices contributing to this cause. However, the authors acknowledge weaknesses and inefficiencies of various participation methods and their inability of establishing a link between the actual needs of communities and official planning decisions. The lack of this interaction undermines the very essence of social sustainability. Therefore, the focus of the analysis presented in this article will be primarily placed on human needs, classified according to Maslow’s hierarchy [

28], and their actual spatial and functional readability, as observed by users.

The article presents two of Belgrade’s super-blocks, which have started the renewal of their open public spaces creating new gathering places—urban hubs. However, they illustrate two different approaches, spontaneous/informal, conducted over the period 2005–2019 (Block 37, New Belgrade), and formal, implemented within the European Union (EU) cultural platform Shared Cities: Creative Momentum (SCCM) between 2017 and 2019 (Block Plato, Vračar). Underlining the social aspect of sustainability, the relationship between local communities and the open public spaces of super-blocks is analyzed and evaluated, revealing the specificities of both initiatives, manifested on social, spatial, and functional levels. The comparative analysis of the two selected cases is conducted within the theoretical framework of Lefebvre’s ‘

right to the city’ and ‘

right to urban life’ [

29], stressing the importance of urban space and its attributes for urban life and activities as an essential anthropological need [

30]. Since the New Urban Agenda [

31] stresses the importance of quality public spaces as one of the most valuable urban features, while place attachment, place identity, and a sense of community contribute both to the public participation and community life of neighborhoods [

32,

33], the presented examples also provide insight into the local practice(s) of the placemaking process, community participation, and participatory design [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Bearing in mind that place attachment theory [

32] considers the establishment and development of individual and collective ties to a spatial setting, both cases will be analyzed through the spatial and functional changes of their open public spaces. Although initiated in a different manner (spontaneous/informal vs. formal) and modified during different time-spans (approximately 14 years vs. 2 years), these changes resulted from a collaborative placemaking effort(s), which followed the needs and preferences of local inhabitants, while simultaneously improved physical and social identities of targeted places.

This article consists of six parts. The sources used for the study and the applied methodology are presented after the introduction, while the third part presents two selected examples—Block 37 and Block Plato; their spatial and functional characteristics, and the main outline of the implemented placemaking processes resulting in new urban hubs (stakeholders/actors, phases, activities, and interventions). The fourth part presents the results of comparative analysis (before/after spatial interventions), evaluating the achieved level of social sustainability according to the quantitative and qualitative indicators identified by interviewed users [

28]. The next part discusses the effects of two presented placemaking approaches to social sustainability in the local context, while concluding remarks provide the guidelines for establishing similar urban hubs in deprived or alienated local communities of super-blocks, which might improve the quality of life and social interactions in other Serbian cities.

2. Methodology

The study of the selected super-blocks was based on the review of the available documents—the Master Plan of Belgrade [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]; detailed and regulation plans for blocks 37 and Plato [

45,

46,

47]; competition entries for Block 37, urban, and architectural plans of Block Plato [

45,

46,

47]; reports and accompanying material of the project Shared Cities: Creative Momentum (SCCM) [

48]; the national Law on Planning and Construction [

49]; and the 2011 and 2018 Statistical Yearbooks of Belgrade.

Furthermore, the comparative analysis of both cases targeting the social sustainability of blocks was conducted according to the data collected by authors (Block 37) and the research team of the SCCM project, which included the Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) Belgrade International Architecture Week (BINA), and several collaborators (including one author). The data were based on the results of observations (before, during, and after the placemaking process of the hubs within the blocks) and interviews covering the overall periods of conducted activities. The interviews included basic data on interviewees (age, gender, parental status, profession, free-time activities), as well as a set of questions providing qualitative insight into following topics:

- (a)

Place identity and place attachment (main elements of atmosphere and recognizability, gathering places, environmental concerns);

- (b)

Community (well-being, interaction and exchange, participative activities and initiatives, shared experiences);

- (c)

Activities (type, intensity, quality, facilities, routes of movement);

- (d)

Physical structure (buildings, open spaces, green areas, playgrounds, accessibility, maintenance, equipment);

- (e)

Safety (block/neighborhood, streets, open spaces, corridors, building entrances).

Forty people were interviewed in Block 37 and 138 people in Block Plato. In both cases the ratio between local inhabitants and guests was around 90:10%. The interviews were semi-structured and in Block 37 were conducted by a one-on-one approach. In Block Plato, the first set of interviews (38 of them, before the intervention) used the same method, while the second set, focused on the evaluation of project results, combined one-on-one and online approaches (100 interviewees). The gender structure (female/male) was approximately 50:50% in Block 37, while in Block Plato is was 65:35% in the first round of interviews and 68:32% in the second round.

The interviews had an important role in clarifying the users’ perceptions of the social sustainability of space. They revealed that individual and community needs represent the main elements of personal interpretation. Therefore, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, frequently used as a foundation for research on social sustainability [

26], was applied for classification of obtained information and the comparison of before/after situations. According to this, seven categories of needs were considered (biological and physiological; safety; belongingness; esteem; cognition; aesthetic; self-actualization), while the transcendence needs were omitted due to their specific, non-spatial manifestation.

The interviewees were also asked to correlate spatial and functional changes of space with their subjective opinion on the level and quality of needs’ fulfillment, which resulted in a set of quantitative and qualitative indicators listed in

Table 1. For example, when asked to explain a certain improvement, which contributes to social sustainability, the interviewees would mostly refer to a greater number or intensity of certain spatial and functional elements, their presence/absence, or the subjective level of satisfaction (ranked 1–5). Consequently, the fulfillment of biological and physiological needs was estimated according to the number of service activities, accessibility to public spaces, the amount of green areas and active open spaces, and the quality of the microclimate. The level of safety was defined by the quantity of street lights, type of surveillance, position and efficiency of protective barriers, and the hierarchy/separation of different circulation routes. The belongingness needs were decoded through the functional flexibility of open spaces, the level of place attachment, and the number and spatial formation of gathering places, including new urban hubs. Esteem needs were manifested through the type of placemaking initiative, the involvement of various stakeholders, and the role of the community in both placemaking and maintenance. The need for cognition was detectable through the intensity of various community-shared activities/events and public promotion, while the survey of waste management and spatial maintenance contributed to the fulfillment of aesthetic needs. The level of self-actualization was reflected in the community’s willingness to participate in the placemaking process, while the integration of all users and their shared development vision were also used as indicators.

The quantitative data were obtained by observation, while qualitative data originated from interviews.

3. Case Studies—Emerging Urban Hubs: Block 37 and Block Plato

The selected blocks 37 and Plato represent two examples of a

super-block urban unit, also described by different plans as a

residential neighborhood [

40], a

local community [

41], and an

open block [

42,

43,

44]. Initially, this type of urban block was used as a connecting tissue between the existing urban areas of Belgrade and peripheral settlements. Block 37 was created during the 1960s in New Belgrade, as a new administrative center of the capital city connecting the traditional core of Belgrade and Zemun, while Block Plato was built in the 1970s, as a part of urban reconstruction conducted in the border areas of centrally located municipalities (Vračar municipality).

Although statistical data for these two blocks are not available, the population data from the municipalities of New Belgrade and Vračar reveal some demographic trends [

50] (

Figure 1). The population of New Belgrade (214,506 in 2011) had its peak in 1991 after which the decline started due to migrations and economic crisis, while the number of inhabitants in Vračar has (56,333 in 2011) continuously declined since 1961. However, the number of households in New Belgrade is increasing due to new housing (81,073 in 2011) and in Vračar this number has been stable since 2002 (25,236 in 2011). According to the 2011 census, in both municipalities women slightly outnumber men, and in both municipalities the population aged between 25 and 65 years is dominant, followed by the group over 65 years, and children up to 14 years. Considering the level of education, in 2011 the major share of inhabitants in New Belgrade had secondary (47%) and higher (30%) education, while in Vračar, 42.5% had higher education and 39% secondary. The data on average earnings demonstrate an increase in New Belgrade (from 553 euros in 2011 to 882 euros in 2018), as well as in Vračar (468 euros vs. 666 euros).

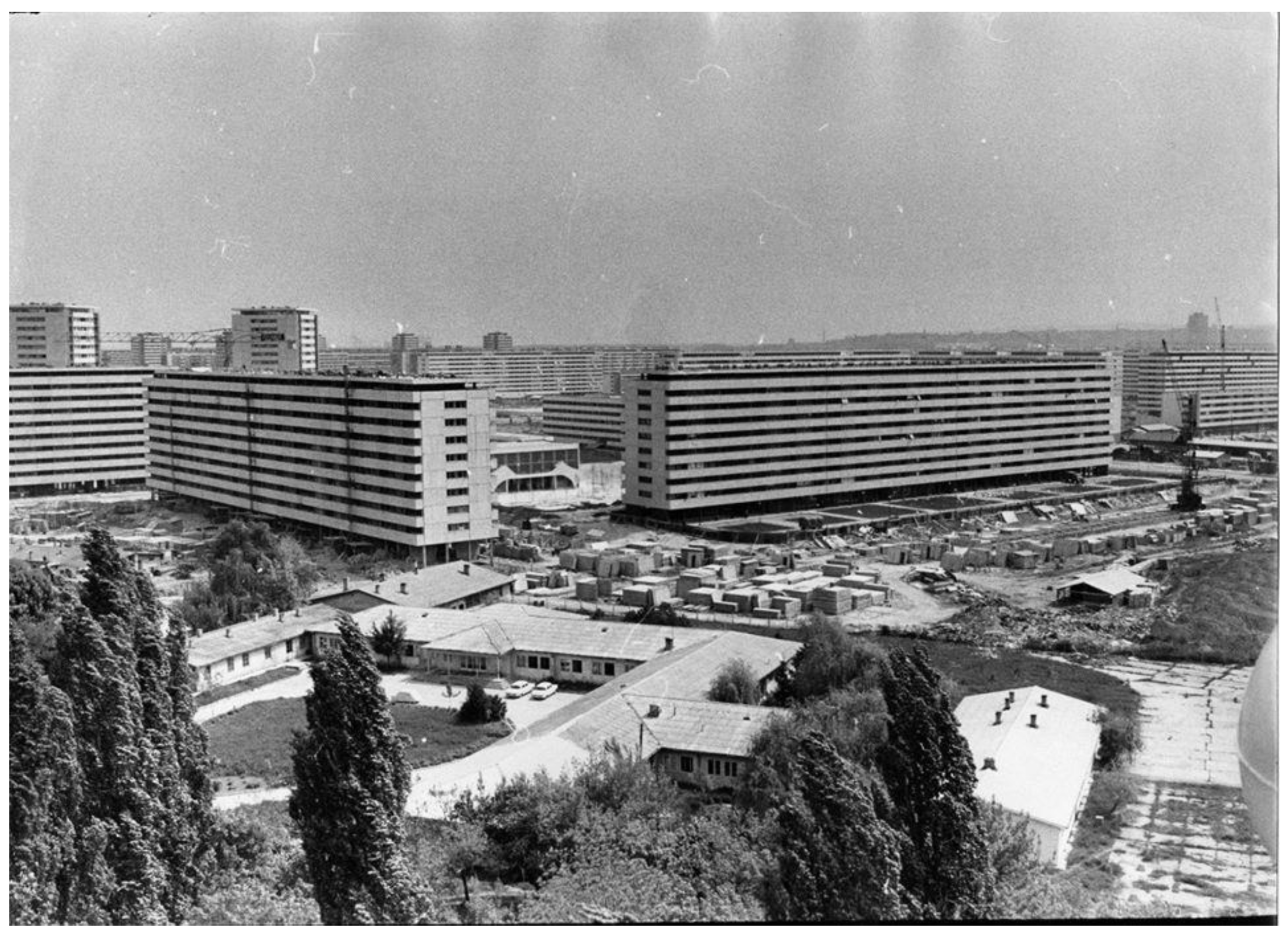

3.1. Block 37—The Spontaneous Urban Hub

Block 37 is a segment of the larger system (the so-called third region of the New Belgrade municipality), positioned between three primary roads connecting the area to Belgrade’s old cores and Narodnih Heroja street, which is the main axis of the third region (

Figure 2,

Table 2). It was conceived in 1961 (

Figure 3), within a general Yugoslav competition launched for three neighboring blocks (33, 37, and 38), and the third region center (within blocks 34 and 40), while the detailed plan of the area was adopted in 1963 [

45]. The construction of the blocks was undertaken between 1966 and 1970, when all the planned kindergartens and two primary schools were built. Although the housing construction was also intensified, the community and regional centers were not initiated in this period, reducing living comfort and causing a lack of cultural and social activities for the growing community. Over the years, Block 37 did not change its structure, although two commercial buildings were added in 2008 and 2009.

After the period of the socio-political turbulences in the 1990s, the open public space within Block 37 was devastated due to the changed concept of ownership, which consequently reflected in poor maintenance of the whole area. Before the 1990s, the apartments in the block were owned by the Yugoslav Army, which was in charge of the maintenance of public domain—open spaces, facades, flat roofs. However, during the 1990s these apartments became private property, the maintenance institutions of the (ex)Yugoslav Army became firm with unresolved status, and there was no appropriate substitution for the previous system. Furthermore, the number of children actively using public space decreased due to intensive emigration/brain-drain triggered by the unstable socio-economic and political situation. The first decade of the 21st century also brought lifestyle changes caused by the intensified use of the Internet, shifting the interaction of younger generations from physical to virtual space. However, around 2005 a spontaneous gradual change in the block started to occur (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

The first initiative was launched by one of the original residents (living there since the 1970s) who acted as a warden of a building community. She asked the city utility company to replace a broken bench in front of her entrance with four new ones. Although its position was next to the main axis leading to a bus stop, it was always an unattractive, empty, and devastated spot. However, after the intervention, four new benches appeared and become a very popular gathering place, and a local urban hub for both older people (daytime) and younger residents (evening). After 2009, when two business buildings were built along the Boulevard Milutina Milankovića, and next to the ‘four benches’, this spontaneous hub became the most favorite (and nearest) place for coffee breaks of their employees. In 2017, a regular coffee shop was built next to the ‘four benches’, transforming an empty space into the most prominent gathering spot in this area. Along with this evolving hub, Block 37 has several other gathering places. Created by the local community out of used materials and outdated furniture, they are composed of several benches, chairs and/or tables, enabling the comfortable use of open space. This practice has also represented the continuation of interaction, which inhabitants established during the NATO bombing in 1999, when local communities all over Belgrade spontaneously increased the level of mutual psychological support and relief during the periods in between daily air strikes.

The upgrading of the playgrounds in the block has also been part of spontaneous placemaking. Since the biggest playground in Block 37 was not renovated since the 1970s, it was in a very poor condition, with only a few pieces of original equipment. During 2010, the local community started improving the condition of the site using available materials. Simultaneously, they created an open-air gym next to the access path. It was protected by trees, creating a shaded gathering place defined by two benches around a table. In 2016, this particular spot was enlarged and reconstructed simultaneously with the reconstruction of the biggest playground and sports grounds, conducted by the Municipality of New Belgrade. Since then, it has been the most popular gathering place within the block.

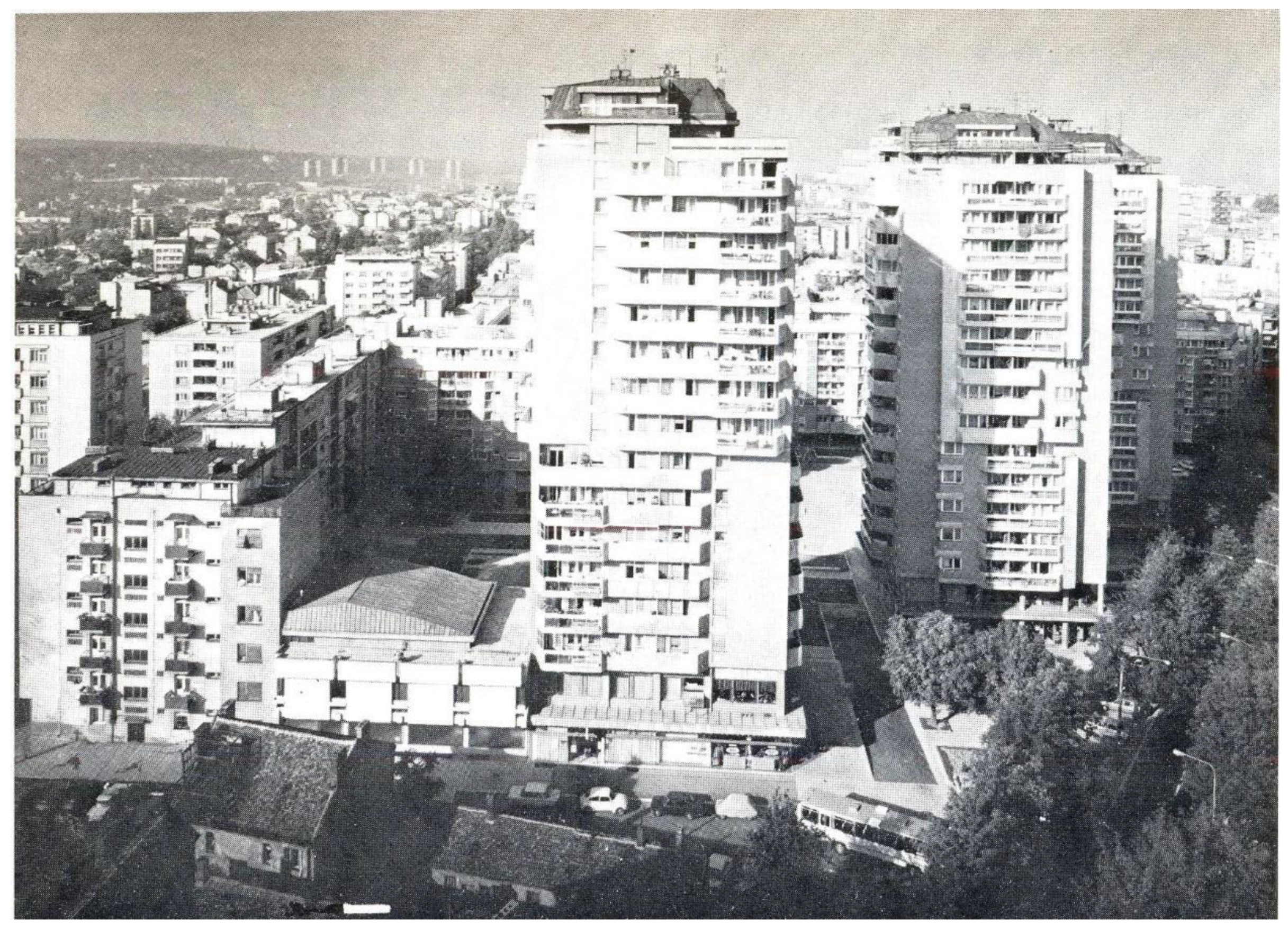

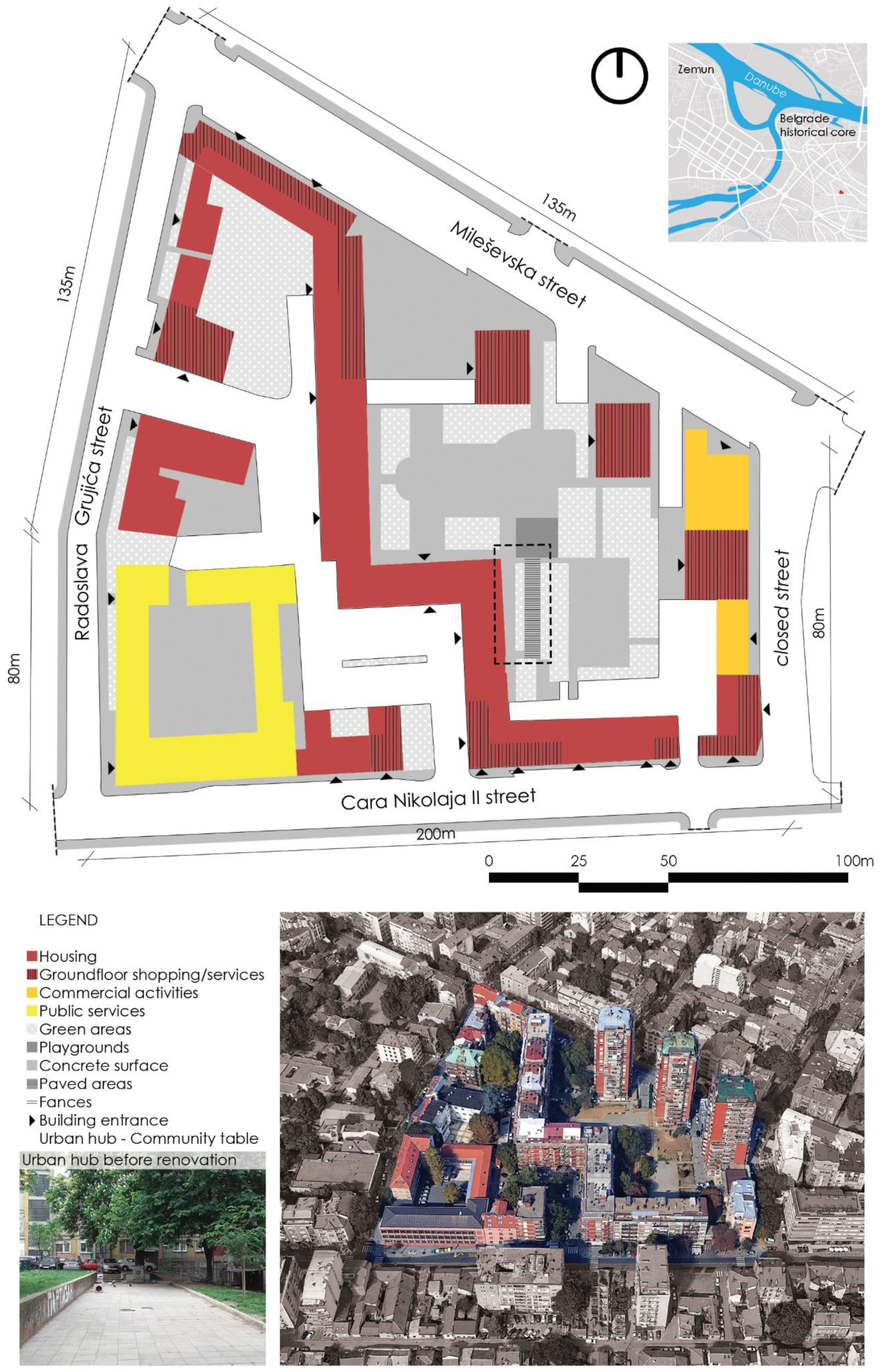

3.2. Block Plato—The Project-Driven Urban Hub

Block Plato is a super-block situated in Vračar, one of the central Belgrade municipalities. Built in the 1970s, it represented a specific approach to the reconstruction of centrally located urban blocks, which was considered by several post-war Yugoslav architects (e.g., Nikola Dobrović, Branko Maksimović) and implemented in some other Belgrade areas (e.g., Profesorska Kolonija, 1947–1948; Inex— office/apartment block with a tower, 1969–1985). The urban plan of the block, based on the principle of interpolation into an existing city grid, was created in 1968, while the project for the reconstruction of the space between the streets Save Kovačevića, Vojvode Dragomira, 14. Decembra, and Jiričekova was completed in 1971 (

Figure 6). The block is composed of existing public buildings (schools, churches, etc.) and new ones, designed in accordance with the aesthetic of international style—a long meander building and three vertical towers surrounding an open space [

51] (

Figure 7,

Table 3).

The main idea behind this approach was to upgrade the existing buildings and replace smaller and dilapidated structures with new ones, while simultaneously increasing the concentration of housing, open and green spaces, and underground parking capacity [

46]. Furthermore, the open public space within the block (called Plato) was slightly cascaded and divided into several fields for playing and socializing, while the surrounding streets continued to provide various central activities, unlike the streets in New Belgrade, which were planned exclusively as traffic arteries. However, the public space within the block became neglected due to poor maintenance caused by a changed ownership structure. Therefore, the regulatory plan [

49], targeting the reconstruction of the blocks between the streets Maksima Gorkog, Mileševska (ex-Save Kovačevića), and 14. Decembra, proposed the improvement of life and work quality, as well as the specific urban transformation of existing blocks. The plan also mentioned the necessity of urban competition for the design of open public spaces and new buildings, but nothing happened until 2017, when Block Plato and its open public space became one of the urban hubs within the project Shared Cities: Creative Momentum (2016–2020), dealing with the social role of civic initiatives in improving contemporary cities. Co-funded by the Creative Europe program of the European Union, the project included Belgrade, Berlin, Prague, Bratislava, Katowice, Warsaw, and Budapest.

The whole idea of an urban hub in Block Plato was conceptualized and organized by the Association of Belgrade Architects (ABA) and the Belgrade International Architecture Week, while Park Keepers (

Čuvari parka), a local NGO, was selected to implement its activities in the Plato public space, after an open call in 2016. The urban hub project was based on the newly developed participatory planning methodology, which included research and data gathering; data analysis; work with stakeholders (via discussions, workshops and exhibitions); and community building (i.e., the implementation of mutual ideas) [

52].

The study was conducted during 2016 by a multidisciplinary team of anthropologists and architects and results indicated that the main problems were related to space (the proximity of buildings, lack of playgrounds, and park equipment, accessibility), low social dynamics and interactions, poor maintenance and hygiene, safety, insufficient number, and low quality of outdoor activities. Therefore, it was necessary to identify dysfunctional and neglected areas, which could be transformed without disturbing already established spatial links connecting functional gathering spaces (football and basketball courts, children’s playgrounds, benches, etc.) [

53].

Focusing on the local context was necessary in order to understand the setting and its micro-processes and conduct contextualized planning and placemaking [

54]. The activities held between February 2017 and May 2018 included community engagement, participation, and sharing (

Figure 8). They consisted of two festivals, one international conference, six workshops, two exhibitions, one discussion, three publications, and twelve neighborhood events with two neighborhood creative charity events [

55]. The spatial outcome of all these efforts resulted in the painting of Plato’s pavement and the establishment of the Community Table with mobile seating facilitating spatial and functional flexibility. These new elements created a new urban hub (

Figure 9), as a result of community ideas, professional design, mutual collaboration, and support provided by more than 20 stakeholders (including the Municipality of Vračar), and donors (e.g., Tikkurila). They all had an active role in the process providing space, assistance, equipment, and other resources, while simultaneously contributing to the overall sense of belonging, sharing, and care for the neighborhood.

4. Results

The placemaking processes conducted in Block 37 and Block Plato have directly and indirectly triggered multiple changes influencing the level of social sustainability (

Table 4). Open public areas of both blocks have been additionally activated by new or remodeled urban hubs, whose upgraded social, spatial, and functional performances have stimulated the gathering and interaction of inhabitants. Since interviewed users (both residents and passers-by) evaluated the results of placemaking by assessing their individual and community needs, the condition of blocks before and after the intervention(s) is identified and compared.

4.1. Biological and Physiological Needs

The observation conducted over the period 2005–2019 in Block 37 shows that the types of service activities have remained the same, but their quantity and quality have improved (11 to 15 places providing postal and money exchange services, shopping—basic and specialized, business facilities, library, coffee shops, and restaurant service). Public open spaces remained accessible to all groups of users, although some building entrances are still unfit for users with limited mobility (including older people and baby carriages). The total green area remained the same (6.7 ha, 9 m2/inh.), but the overall area used as an active open space has increased due to activation/extension of some previously neglected places, slightly increasing the share of concrete surfaces over green ones (97:3%). The interviewees also emphasize the abundance of greenery, which has a positive effect on the microclimate.

The placemaking process of an urban hub in Block Plato also had a positive impact on the number of service activities, increasing their number (10 to 14). Currently, it includes basic and specialized shopping facilities, cultural activities, a gym, coffee shops, and restaurants mostly oriented towards local users from neighboring blocks. The open space of the block is accessible to all identified groups of users, but with the limited accessibility of several building entrances, which were not adapted following the transformation. The previous ratio between actively used concrete and green areas has not changed, and even though interviewees were dissatisfied with the share of shaded sitting areas, there were no improvements.

4.2. Safety Needs

Due to continuous placemaking efforts and the establishment of active community hubs, the general safety of Block 37 and its public spaces has increased. The higher intensity of community activities during the last few years has influenced better public lighting (currently 223 street lamps within the block and 46 in bordering streets), which was emphasized by interviewees. Human surveillance is active due to a higher interest of people in activities in the block (as participants or observers), while the establishment of new service places introduced video surveillance as well. The physical barriers exist mostly in the form of street parking, while the ground level of buildings have also been closing rapidly since 2005, in order to utilize the space of previously existing corridors connecting public spaces of the block. The original hierarchy of the circulation routes has mostly remained and is described by users as safe, allowing good connectivity of cycling, roller-skating, and walking paths. However, the increased number of cars has led to the occasional interruption of pedestrian areas, temporarily being used for short-term parking, thereby decreasing levels of satisfaction.

In Block Plato, one of problems detected before intervention was very poor lighting, which has since improved (both within the block and along bordering streets), but some interviewees still find it unsatisfactory. However, the area is generally described as safe, due to the presence of people involved in different activities or observers from windows. Several buildings have recently obtained electronic surveillance and some service facilities now have security guards. The trend of converting open building corridors into shops or smaller services was evident in this block too, but even though parts of the public space are occupied, the presence of people has increased and lighting has improved. The block still has the original hierarchy of circulation routes and barriers protecting the pedestrian quality of public space, but there is a lack of integration with neighboring blocks due to a radical difference in urban fabric. The surrounding blocks represent examples of traditional, compact urban tissue, and they do not have physical and visual permeability. The users with children also underlined the necessity of protective barriers around playgrounds (which have still not been introduced), while the problems of damaged pavements and shattered glass were solved by the establishment of the urban hub.

4.3. Belongingness Needs

Although the number of activities performed in public space of Block 37 has remained unchanged, the information obtained by interviews and observation indicate that their intensity (number of people involved, frequency during weekdays, duration) has increased, contributing to the higher flexibility of social hubs. The number of gathering places has doubled, providing higher place attachment of the community through the interaction of people involved in sports, passive and active recreation, urban gardening, playing, walking, sitting, and talking. This is a two-way process of sharing and exchange, since gradual placemaking was triggered by social interaction, while new or renewed facilities and gathering places attracted more users (active and passive participants), providing a spatial framework for community interchange and further initiatives. The interviewees underlined the emerging trend of intergenerational interaction, which was not the case before the establishment of urban hubs.

During and after the placemaking process in Block Plato, the number of activities has significantly increased, contributing to the overall flexibility of the public space. Higher numbers and the intensity of community activities, such as gardening, gaming, different organized workshops, neighborhood actions, and exhibitions have stimulated better place attachment. These actions resulted from both the project initiative and individual efforts, contributing to the community advancement, its identification with space, and the overall social sustainability useful for further upgrading. The role of a Community Table, as a new urban hub, was also confirmed through post-project evaluation interviews. The number of gathering places has increased (four to six), attracting more users and offering different possibilities for interaction and exchange.

4.4. Esteem Needs

Before 2005, the only initiatives related to the open public spaces in Block 37 were conducted through official channels of (in)efficient maintenance. However, since 2005, the informal placemaking conducted by the community has become the main driver of all spatial changes, with an immense impact on community self-esteem, with a three-fold effect: it provided socially sustainable places for local inhabitants, increased the visibility of the community and its efforts, and instigated further spatial changes of the block, which attracted other users. Consequently, the number of involved stakeholders increased too, including the City Greenery of Belgrade (in charge of the reconstruction of a playground and its current maintenance), the Municipality of New Belgrade, and cafe-restaurant owners. The community is nowadays also involved in the maintenance of all spaces, either as the main actor or as a support, which represents an important indicator of its active involvement in placemaking and place-keeping.

The local community in Block Plato was initially doubtful when considering the effects of a bottom-up approach to a placemaking initiative, especially knowing usual negative reactions from municipal authorities. However, the positive outcome influenced a higher level of self- and public-esteem. The process was conducted within a formally organized framework of the EU project, but the community, as well as an impressive number of more than 20 stakeholders, were active participants from the beginning, which was not the case before 2016 and the launch of the SCCM project idea of urban hubs [

56]. Until then, only the City Greenery, the Land Development Public Agency, and the Municipality of Vračar were officially in charge public spaces. Additionally, in 2015 NGO

Park Keepers organized several events involving local residents (spring cleaning and art workshop), supported by the Municipality of Vračar. After the first spatial results (pavement renovation), more people joined the initiative, while the Land Development Public Agency, in cooperation with the SCCM, provided a connection between local community, institutions (e.g., Municipality of Vračar, City of Belgrade etc.), and NGOs in charge for mediation and implementation of public participation (Park Keepers, BINA, ABA). Although before 2016, the local community was not interested in the maintenance of public space, after the placemaking process they have spontaneously become involved, providing further care of the hub.

4.5. The Need for Cognition

This category of needs is best manifested though various community activities and events which already existed in Block 37 before placemaking activities, but according to interviews, they are now intensified and stimulated due to a more comfortable, safer, user-friendly spatial setting accessible to all. The activities are mostly spontaneously conducted by individuals and/or specific interest or age groups, but organized community cleaning of new/reconstructed gathering places signifies a closer involvement with public space and a higher level of environmental awareness. There is no public promotion of activities, even though the block became locally known as a good example of informal, community-driven initiatives.

The process of participation in creating a new urban hub in Block Plato was based on a number of community activities, which provided better understanding of the context, processes and users of the place, enabling transmission and exchange of knowledge related to the environment, needs, and interests of involved social groups and other stakeholders. From different kinds of participatory projects and interviews, to organized neighborhood cleaning, arts & crafts workshops, bazaars and exhibitions, these activities bolstered both individuals and the local community. These activities increased the Block’s public recognizability through different media channels, promoting the neighborhood as a role model. The whole process of participation and implementation was also presented in a video, revealing the role of the Community Table, as a flexible focal point of intervention, community sharing, (re)cognition and identity.

4.6. Aesthetic Needs

Since spatial upgrading in Block 37 influenced a high number of users, waste management has become very important. Although the number of street wastebaskets has increased, it is still insufficient and their distribution, as well as maintenance, are inadequate. This has a negative impact on both the visual and environmental quality of public space. Street furniture, pavements, and green areas are now better maintained, and even periodically restored (in accordance with available funds), but the major problem is the state of the dilapidated facades which are only occasionally painted, mostly on the ground floor level.

In Block Plato, the design of the urban hub conducted by professionals and based on community input has, according to interviews, increased the level of aesthetic appreciation and influenced further visual improvements of the space, although not sufficiently. The number of street wastebaskets has increased, but there are still several very poorly equipped and maintained areas. It is also visible that the maintenance of street furniture, pavement, green areas, and facades is better, although it could be improved.

4.7. Self-Actualization Needs

Considering current processes in the public space of Block 37, it is evident that all groups of users are integrated into the maintenance process. The community remains willing to take part in any new placemaking initiative, which would improve the condition of gathering places, but there is no community vision or a preferred development scenario for this urban hub, which might influence the level of its social sustainability in a long run. However, that could be a source of future flexibility in adjusting the public space to the changing needs of users.

The initial hesitation of the local community in Block Plato was overcome during the activities of the NGOs in charge for mediation in the placemaking process. All groups of users were integrated into the process to a certain extent; however, the initiative to create a local community NGO was not successful. Recently, the group composed of residents and local stakeholders expressed interest in launching and conducting the next phase of implementation, which would convert a parking space into a green area. Following this initiative, NGO BINA, as one of the mediators, started negotiating with residents and the nearby cultural institution Božidar Adžija. Considering these activities, it could be said that there is a community vision for further development of the space, which would ensure its social sustainability in the long run.

5. Discussion

The cases of Block 37 and Block Plato represent two possible approaches to the placemaking process of large urban units of super-blocks. Facing the problems generated by decades of poor maintenance and the negligence of spatial resources, which were originally planned as open public spaces with a number of activities, these blocks (re)created their community interest and place attachment.

Block 37, as an example of informal, self-organized activities directed towards community well-being, reveals that even small spatial interventions conducted over a longer period, with limited/available resources and a low involvement of institutions, can trigger a chain-effect between residents and other local stakeholders, willing to contribute to the overall quality of gathering places. The increased spatial performances influence a higher intensity of activities, attract more users, and provide better visibility of community needs and their place attachment. They also create a sustainable social capital, which serves as an instigator of placemaking at an institutional level, ‘awakening’ the attention of local authorities. This could generate an additional impact on sustainability of community-initiated placemaking activities, providing financial, administrative, and/or organizational support for renewed urban hubs, i.e., the places of gathering, sharing, and exchange in super-blocks. Considering the small scale of intervention, whose estimated costs were around 2400 euros (placing of benches, initial cleaning of the area), this model could be applied by other local communities with a strong sense of mutual wellbeing and place attachment, but only if the activities are based on a high level of self-organization and community awareness. However, the overall social sustainability also depends on further maintenance of public spaces/urban hubs, which demands more active involvement of municipal or city institutions. In this case, it is estimated that average monthly costs would be around 400 euros, which could represent a problem if only the local community is in-charge; due to limitations imposed by general income levels and questionable willingness of all users to contribute equally.

The case of Block Plato reveals the possibility for motivating local communities with low interest and expectations regarding a community space, especially given formal support and mediation (both organizational and financial). In this example, the EU-funded platform enabled the implementation of a vision shared by the local NGO Park Keepers and professionals (BINA and ABA). This joint effort provided initial momentum for conducting research related to community needs, instigating their mutual networking, and further participation in arranging and maintaining the established urban hub. The community also obtained social capital, which increased its general visibility, opening new channels for mutual cooperation. Being perceived as an example of good practice certainly presents a competitive advantage for further development (and funding) possibilities, but it is also an element contributing to a higher esteem, (re)cognition, self-actualization, and the sense of belonging of both individuals and the local community using a ‘reinvented’ gathering place [

53,

57]. Considering the fact that overall costs of integrating urban hub—Community Table into Block Plato were about 12,000 euros (materials, production, and co/production of events, communication, catering, etc.), and the estimation of maintenance is 2400 euros per month, it is evident that this model needs stronger institutional support, at the levels of financing, management and maintenance.

Although institutions, professionals and NGOs did not have similar roles in the placemaking processes, both initiatives have enabled local residents to create better living environments. The importance of community and its proactive character should be underlined as an important factor of social sustainability, but residents alone should not be the only facilitators of interventions. However, their active involvement is crucial, especially in a post-implementation phase, which verifies the actual level of community engagement and its identification with a created/renewed urban hub.

6. Conclusions

The concept of a functionalist city promoted the model of super-block as the main constitutive element of a physical and functional structure, enabling easy access to services, a higher possibility of social contacts, and closeness to nature [

58]. The open public spaces within super-blocks were conceived as traffic-free areas providing well-being for the local community and serving as flexible gathering places suitable for human interaction, passive and active recreation, and children’s play. Embraced as a preferred model of urban reconstruction after WWII, this concept was applied in Belgrade and other urban centers of ex-Yugoslavia, as the solution for both new settlements and the destroyed and/or outdated traditional urban tissue. However, the main values of this concept have become challenged, especially after the period of socio-economic transition in the 1990s. This period had a severe impact on the overall condition of super-blocks, in social, spatial, and functional structural terms. Besides globally recognized problems related to this type of spatial organization (e.g., alienation, safety, the absence of place/community attachment, and interaction, etc.), the local context triggered issues related to the maintenance of public spaces and buildings, which further degraded urban environment.

The cases of Belgrade’s blocks 37 and Plato represent two approaches to the placemaking process (formal and informal), conducted in order to improve the condition of public spaces within super-blocks. The renewal of neglected areas enabled the (re)establishment of gathering places as specific urban hubs, which are flexible, clean, safe, and available to all. However, the process of placemaking, based on the active participation of local residents, represented the first step of community activation, which continued through collaboration with other stakeholders. In Block 37, the whole process has been self-organized since 2005, but it has influenced further changes and gained the institutional support of the Municipality of New Belgrade. Block Plato was activated in 2016 through the collaboration of NGOs, relevant institutions (both at city and municipal levels), professionals, residents, and other local users. Although the project activities covered a much shorter period of three years, they were more intense and focused on organized research and participatory design, resulting in an iconic project of a Community Table becoming a focal point of the community; a symbol of the participatory process, and a legacy for future actions. Through placemaking activities, both blocks have influenced the overall level of social sustainability, providing comfortable settings for gathering, activities and movement [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63].

The importance of these two examples is visible on other levels as well. Although implemented with different approaches and initial intentions, the public spaces of newly activated urban hubs testify that their sustainability relies on their ability to attract various groups of users in different periods and by different activities. These actions may be conducted even without official financial support, with available local resources, but some special events need adequate logistics. The maintenance of street furniture and other equipment should be conducted regularly in order to provide functionality and safety. Although every community needs to develop awareness on the value of public property, the urban authorities have to be in charge of regular monitoring and maintenance. Furthermore, one of the problems detected in both cases is related to the level of legislation targeting both the limitations considering the use/ownership of public places and the process of participation. The division of competence between the territories of the City of Belgrade and the Republic of Serbia often represents a drawback since most of the public spaces are under the jurisdiction of the Republic of Serbia, while responsible institutions exist at the city level. Consequently, permit procedures are long, complicating development and maintenance issues. Meanwhile, the Law on Planning and Construction [

49] tackles economic, social and environmental sustainability through an integrated planning approach, but it is not sufficiently interwoven with public participation in all phases.

The experiences of blocks 37 and Plato could be used on both local and municipal levels for supporting similar initiatives and facilitating placemaking process, including planning backup, decision-making, multilevel collaboration, and implementation. However, their implementation in historical urban blocks, with different spatial features, which do not include similar types of integrated public open spaces, would be even more difficult due to the property rights of building lots. Nevertheless, these examples represent a valuable contribution to the ongoing debate on social sustainability of citizens’ participation in the Serbian context, especially in the domain of public realm. These findings have provided an insight into possible manifestations of ‘right to the city’ and ‘right to urban life’ within the framework of social sustainability, demonstrating how an active expression of urban commons creates an encouraging environment for interaction, cooperation and sharing, while strengthening community, its identity, and the sense of belonging. Considering legal and financial challenges, which follow similar initiatives in other local and international settings, the application of both approaches could be modified or upgraded, providing a valuable testing ground for the idea of sustainable self-governance on the super-block level.