Removal of Calcium Carbonate Water-Based Filter Cake Using a Green Biodegradable Acid

Abstract

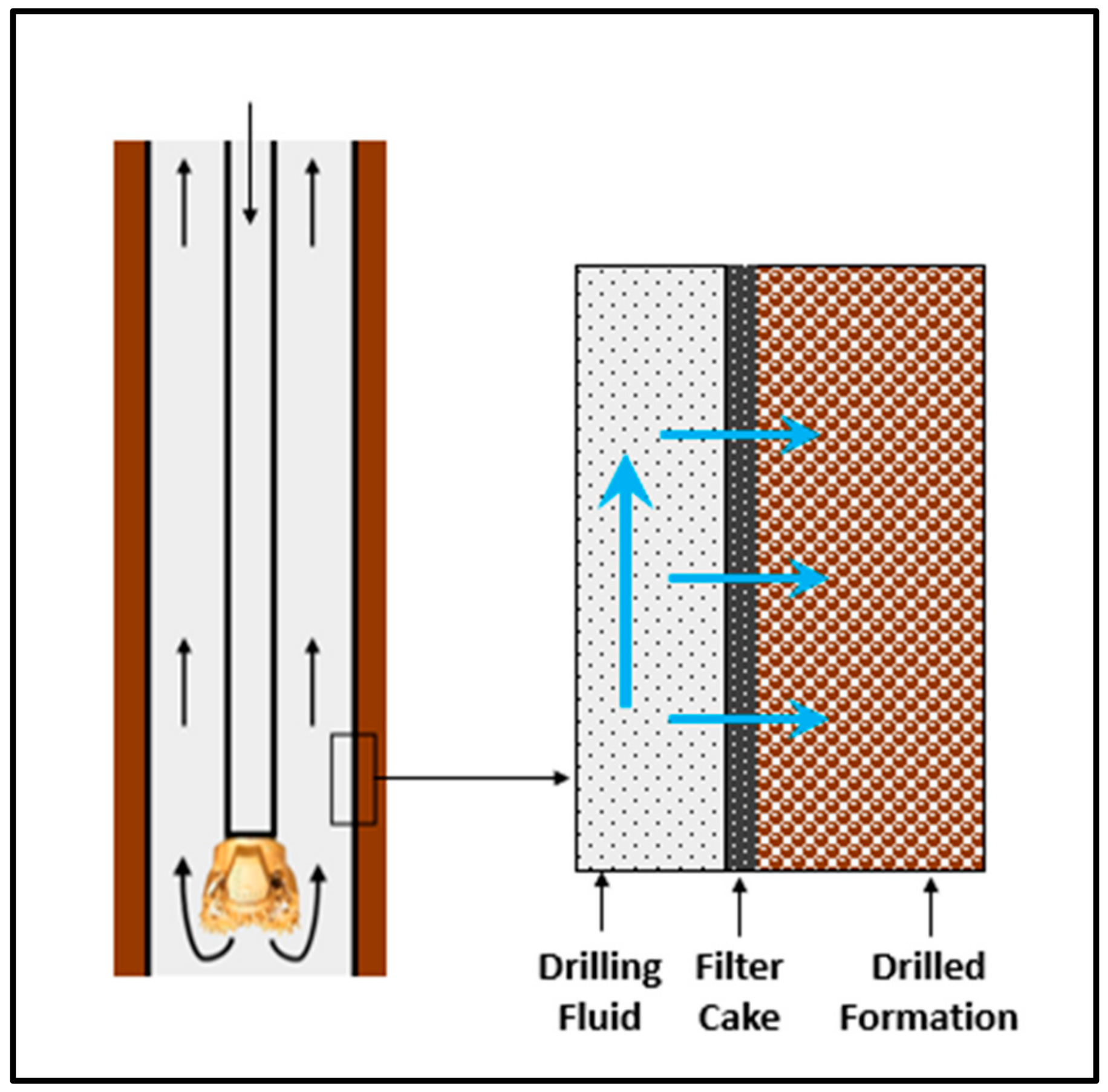

1. Introduction

2. Material

3. Experimental Work

3.1. GBRA Properties and Biodegradation Test

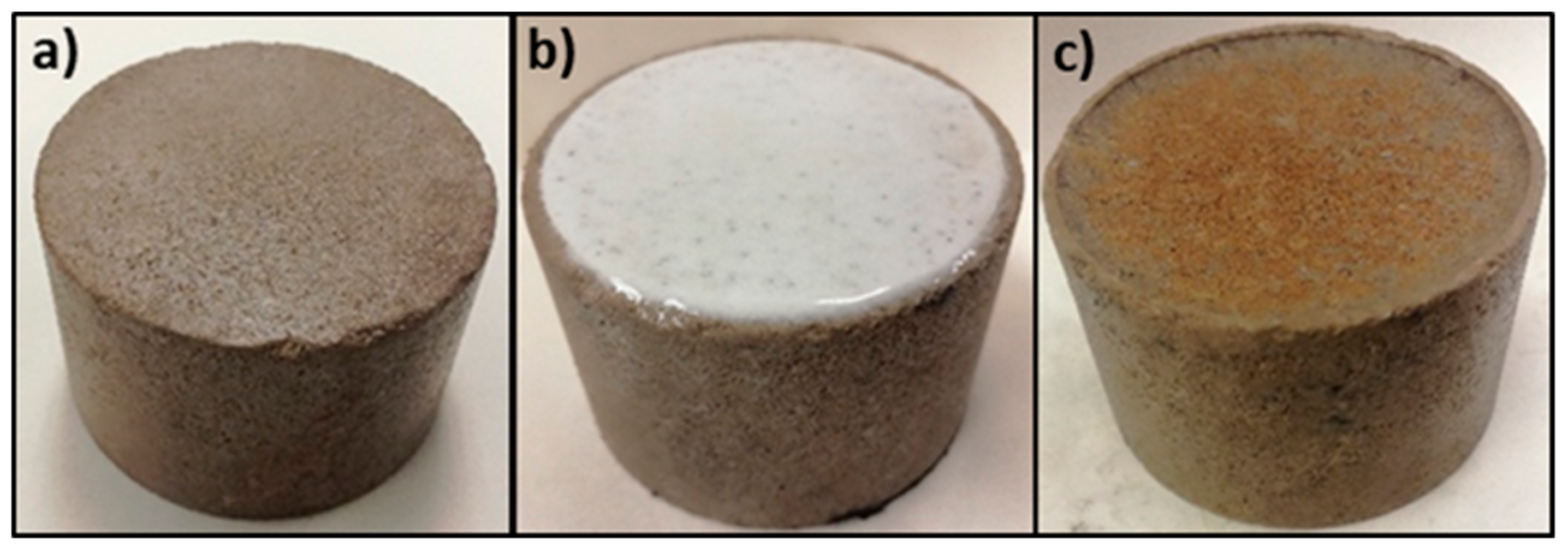

3.2. HPHT Filtration Tests

3.3. Corrosion Test

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. GBRA Properties and Biodegradability

4.2. Filter Cake Removal and Retained Permeability

4.3. Corrosion Test

5. Summary and Conclusions

- The new acid formulation was efficient in removing the calcium carbonate water-based filter cake after 20 h soaking time with a removal efficiency and retained permeability of greater than 90%.

- GBRA (50 wt.%) yielded a corrosion rate of 0.032 lb/ft2 at 212 °F without adding any corrosion inhibitor that is below the standard corrosion rate approved by the oil and gas industry (<0.05 lb/ft2 at a temperature less than 250 °F), while the corrosion rate of HCl (10 wt.%) was 0.68 lb/ft2.

- GBRA (50 wt.%) has a viscosity of µ = 1.58 cP, density of ρ = 1.1 g/cm3, pH of 0.02, and surface tension of σ = 31.4 mN/m. These properties were measured at room temperature.

- The new acid formulation achieved a biodegradation rate of 65% by day 28 using ThCO2 measurement, exceeding the requirements for ready biodegradability; a plateau of 81% was achieved by day 40.

- The high removal efficiency, ready biodegradability, and low corrosion rate make this new acid formulation a good candidate for calcium carbonate-filter cake removal in oil and gas wells.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gordon, C.; Lewis, S.; Tonmukayakul, P. Rheological properties of cement spacer: mixture effects. In Proceedings of the AADE Fluids Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 8–9 April 2008. AADE-08-DF-HO-09. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, J.K. Petroleum engineer’s guide to oil field chemicals and fluids; Gulf Professional Publishing: Waltham, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780128037348. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgoyne, A.T., Jr.; Millheim, K.K.; Chenevert., M.E.; Young, F.S., Jr. Applied Drilling Engineering; Society of Petroleum Engineers: Houston, TX, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-1-55563-001-0. [Google Scholar]

- Caenn, R.; Darley, H.C.H.; Gray, G.R. Composition and Properties of Drilling and Completion Fluids. Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780123838582. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.E.; Al-Majed, A.A. Fundamentals of Sustainable Drilling Engineering. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rabia, H. Well Engineering and Construction; Entrac Petroleum: London, UK, 2001; Chapter 6; p. 203. ISBN 978–1-55563–207-6. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yami, A.S.; Nasr-El-Din, H.A. An Innovative Manganese Tetroxide/KCl Water-Based Drill-in Fluid for HT/HP Wells. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Anaheim, CA, USA, 11–14 November 2007; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Basfar, S.; Mohamed, A.; Elkatatny, S.; Al-Majed, A. A Combined Barite-Ilmenite Weighting Material to Prevent Barite Sag in Water-Based Drilling Fluid. Matererials 2019, 12, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkatatny, S.M. Evaluation of Ilmenite as Weighting Material in Water-Based Drilling Fluids for HPHT Applications. In Proceedings of the Kuwait International Petroleum Conference and Exhibition, Kuwait City, Kuwait, 14–16 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.; Basfar, S.; Elkatatny, S.; Al-Majed, A. Prevention of Barite Sag in Oil-Based Drilling Fluids Using a Mixture of Barite and Ilmenite as Weighting Material. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, J.; Brooks, J.; Dear, S. A New, Nondamaging, Acid-Soluble Weighting Material. J. Pet. Technol. 1975, 27, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, A.; Cliffe, A.; Hodder, M.H.; Young, S.; Lee, J.; Stark, J.; Seale, S. Alternative Drilling Fluid Weighting Agents: A Comprehensive Study on Ilmenite and Hematite. In Proceedings of the IADC/SPE Drilling Conference and Exhibition, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 4–6 March 2014; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tuntland, O.B.; Herfjord, H.J.; Lehne, K.A.; Haaland, E. Iron oxide as Weight Materials for Drilling Muds. Erdoel-Erdgas Zeitschrif 1982, 97, 300–302. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, C. Alternative Weighting Material. J. Pet. Technol. 1983, 35, 2158–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugang, Y.; Guancheng, J.; Wei, L.; Tianqing, D.; Hongxia, Z. Effect of water-based drilling fluid components on filter cake structure. Powder Technol. 2014, 262, 51–61. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2014.04.060 (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Hanssen, J.E.; Jiang, P.; Pedersen, H.H.; Jørgensen, J.F. New Enzyme Process for Downhole Cleanup of Reservoir Drilling Fluid Filtercake. SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry: Houston, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Civan, F. A Multi-Phase Mud Filtrate Invasion and Wellbore Filter Cake Formation Model. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Conference and Exhibition of Mexico, Veracruz, Mexico, 10–13 October 1994; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bageri, B.S.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Al-Mutairi, S.H.; Kuwait, C.; Abdulraheem, A. Filter Cake Porosity and Permeability Profile Along the Horizontal Well and Their Impact on Filter Cake Removal. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Doha, Qatar, 6–9 December 2015; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ba geri, B.S.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Al-Mutairi, S.H.; Abdulraheem, A. Effect of Sand Content on the Filter Cake Properties and Removal During Drilling Maximum Reservoir Contact Wells in Sandstone Reservoir. J. Energy Resour. Technol 2016, 138, 32901. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4032121 (accessed on 1 December 2019). [CrossRef]

- Bageri, B.S.; Al-Mutairi, S.H.; Mahmoud, M.A. Different Techniques for Characterizing the Filter Cake. In Proceedings of the SPE Unconventional Gas Conference and Exhibition, Muscat, Oman, 28–30 January 2013; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, J. Petroleum Engineer’s Guide to Oil Field Chemicals and Fluids, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Chapter 9; pp. 299–316. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803734-8.00009-6 (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- Mcdonald, M.; Li, X.; Lim, B. A formulated silicate-based pre-flush & spacer for improved wellbore cleaning and wetting. In Proceedings of the AADE Fluids Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 15–16 April 2014. AADE-14-FTCE-55. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero, L.; Christian, C.; Halliday, W.; White, C.; Dean, D.; Courtney, G. New spacer technology for cleaning and water wetting of casing and riser. In Proceedings of the AADE Fluids Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 8–9 April 2008. AADE-08-DF-HO-01. [Google Scholar]

- Bageri, B.S.; Al-Majed, A.A.; Al-Mutairi, S.H.; Ul-Hamid, A.; Sultan, A.S. Evaluation of Filter Cake Mineralogy in Extended Reach and Maximum Reservoir Contact Wells in Sandstone Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 5–7 March 2013; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Geri, B.S.B.; Mahmoud, M.; Al-Majed, A.A.; Al-Mutairi, S.H.; AbdulAzeez, A.; Shawabkeh, R. Water Base Barite Filter Cake Removal Using Non-Corrosive Agents. In Proceedings of the Middle East Oil Show, Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain, 6–9 March 2017; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rostami, A.; Nasr-El-Din, H.A. New Technology for Filter Cake Removal. In Proceedings of the SPE Russian Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition, Moscow, Russia, 26–28 October 2010; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, S.K.; Kosztin, B. Magnesium Peroxide Breaker for Filter Cake Removal. In Proceedings of the SPE Europec/EAGE Annual Conference and Exhibition, Vienna, Austria, 23–26 May 2011; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Elkatatny, S.M.; El Din, H.A.N. Removal of water-based filter cake and stimulation of the formation in one-step using an environmentally friendly chelating agent. Int. J. Oil Gas Coal Technol. 2014, 7, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkatatny, S.M.; Mahmoud, M. Investigating the Compatibility of Enzyme with Chelating Agents for Calcium Carbonate-Filter Cake Removal. Arab. J. Sci.Eng. 2018, 43, 2309–2318. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-017-2727-4 (accessed on 20 November 2019). [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Elkatatny, S.; Basfar, S. One-Stage Calcium Carbonate Oil-Based Filter Cake Removal Using a New Biodegradable Acid System. In Proceedings of the SPE Kuwait Oil and Gas Show and Conference, Mishref, Kuwait, 13–16 October 2019; Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): Houston, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elkatatny, S. One-Stage Calcium Carbonate Oil-Based Filter Cake Removal Using a New Biodegradable Acid System. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itävaara, M.; Vikman, M. An overview of methods for biodegradability testing of biopolymers and packaging materials. J. Polym. Environ. 1996, 4, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biodegradability, Ready. OECD guideline for testing of chemicals. OECD 1992, 71, 1–9.

- Sweetlove, C.; Chenèble, J.-C.; Barthel, Y.; Boualam, M.; L’Haridon, J.; Thouand, G. Evaluating the ready biodegradability of two poorly water-soluble substances: comparative approach of bioavailability improvement methods (BIMs). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 17592–17602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Additive | Amount |

|---|---|

| Water | 308 g |

| Defoamer | 0.33 cm3 |

| Xanthan gum | 1.5 g |

| Starch | 6 g |

| Potassium chloride | 80 g |

| Potassium hydroxide | 0.3 g |

| Sodium sulfite | 0.25 g |

| Calcium carbonate (50 µm) | 30 g |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohamed, A.; Elkatatny, S.; Al-Majed, A. Removal of Calcium Carbonate Water-Based Filter Cake Using a Green Biodegradable Acid. Sustainability 2020, 12, 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030994

Mohamed A, Elkatatny S, Al-Majed A. Removal of Calcium Carbonate Water-Based Filter Cake Using a Green Biodegradable Acid. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030994

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohamed, Abdelmjeed, Salaheldin Elkatatny, and Abdulaziz Al-Majed. 2020. "Removal of Calcium Carbonate Water-Based Filter Cake Using a Green Biodegradable Acid" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030994

APA StyleMohamed, A., Elkatatny, S., & Al-Majed, A. (2020). Removal of Calcium Carbonate Water-Based Filter Cake Using a Green Biodegradable Acid. Sustainability, 12(3), 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030994