1. Introduction

The subject of managerial leadership has been widely researched in organizational studies [

1], and even though emerging discussions on the subject continue to evolve, there has been no true quantification and a subsequent accurate definition [

2,

3]. Extent literature suggests that managerial leadership encompasses many levels in an organization, which in itself creates complexity with decision-making. Therefore, the path of sustainable leadership actions within organizations is often fraught with challenges, and leaders have to continually rise to address such challenges as they emerge [

4]. Nery-Kjerfve and McLean [

5] (p. 36) appropriately conclude that “grounding in the crossroads”, being mindful of the current development in organizational and managerial practices while still operating in a relevantly suitable manner to the local setting, is the key to sustainable competitiveness. It is this mindset that Tideman, Arts and Zandee [

6] (p. 17) say is needed for managers as sustainable leaders “to empower their organizations towards the creation of sustainable value.” Seshadri, Sasidhar and Nayak [

7] (p. 5) explain the meditative practices in Hinduism and Buddhism providing insights to

dharma, a Sanskrit term representing “a complex concept which encompasses a wide range of values such as ethics, morality, justice, fairness, harmony and societal order” as a

mandala or pictorial design depicting universal truth. These leadership challenges, though they often provide insights into organizational design change policies and role leadership effectiveness, can manifest as a predicament to the moral code of an individual and the context of situational truth,

dharma sankata, an antithesis to dharma. The recent civil war in Sri Lanka as an outcome of racial and religious unrest is viewed as an antithesis to dharma where the balance of the

mandala is disturbed.

It is these dilemmas that manifest as behavioral concerns of leadership in Sri Lankan organizations that have been explored in this paper. These perceived dilemmas are seen as tensions in corporate sustainability [

8]. Hanh [

8] proposes that corporate sustainability, from an integrative viewpoint, covering economic, environmental and social dimensions and accepting that tensions in corporate sustainability exist, is a challenge for leaders and an agenda for research. Thus, the insights developed in this paper into perceived managerial behaviors should inform sustainable organizational development and leadership in Sri Lanka. In a sense this paper looks at contributions of the eastern tradition to crucial management decision-making practices. As [

9] (p. 763) state, “rich eastern traditions have remained underexplored in contemporary business literature.”

With India’s recent economic growth, there has been some attention given to managerial leadership behaviors in the Indian subcontinent [

7,

10,

11,

12]. Though these studies show evidence of business practices adapting and supporting new global challenges, the West, however, has modest knowledge of the nuances of management practices in the Indian subcontinent generally, where ancient cultural practices have commonly been sustained. The accelerated growth of Asia in the last few decades has prompted a concentration of in-depth studies on societal values as influencers of organizational behavior, and with the increasing economic attention of the Indian subcontinent, this will no doubt also attract researchers to this region [

10,

11,

13]. There are some good reasons why this region has previously been neglected by organizational studies researchers. Firstly, unlike the dominant-cultural societal structure of many of the economically progressive East Asian nations such as China, Japan and Korea, the Indian subcontinent nations, such as India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan are highly complex with multiple languages, religions and customs [

12]. Secondly, the Indian subcontinent is the bedrock of many practicing eastern religions, thus influencing and providing complexity to management thinking [

14]. Thirdly, most of the countries of the Indian subcontinent have experienced ethnic conflicts with an overlay of a strong desire for self-determination, which in the past has translated to socialist-type policies [

15].

It is from this complex cultural base that this paper addresses leadership perceptions of Sri Lanka, often referred to, in the poetic language of the Indian subcontinent, as the “Tear drop of India” or the “Serendipitous Land”.

2. The Theoretical Foundation of Sustainable Leadership

In this paper, we assert that the phenomenon of excellent leadership rises to the occasion if the values of organizational dynamics are known. In providing a framework for this to eventuate, we turn to implicit leadership theory (ILT) as providing the cognitive base where individuals use preconceived notions of the world to interpret their environment and develop behaviors to control it [

16,

17,

18]. This interpretation is consistent with [

19], where they view sustainable leadership as an interactive process of shared values informing leader behavior. Such perceptions form the basis of ILT, where discrete ethical emotions such as personal integrity, spiritual discipline, trust and loyalty and moral anchoring are viewed as powerful inputs to personal perceptions or judgments that influence leadership behaviors [

20,

21]. These inputs are captured within a sustainable leadership framework [

6,

19]. These ethical emotions, as inputs, are further informed by demographic characteristics such as ethnicity, culture and gender in upholding leadership impressions and leadership practice [

22,

23]

2.1. Dharma-Driven Mandala: A South Asian Worldview

The emergent organizational leaders as “managers” of group emotions was first proposed by [

24,

25,

26,

27], where individual group members assume leadership roles by being able to interpret and model emotional responses that best serve the group needs. Therefore, the leader emerging strategically to the occasion as the group need arises, is the focus of several conditions highlighted within the implicit understanding of the environment [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. That is, each manager, as strategic leader [

29], being able to understand the degree of empathy, aspirations, expressions and ambiguity required is an implicit condition that will provide the framework for excellent leadership, which will be the subject of investigation in this paper. Implicit theories as a foundation for leadership studies suggest a cultural bias, which makes the emic rather than etic approach more suitable to study leadership excellence in Sri Lanka. This paper was developed in support of the need for leadership to emerge based on implicit knowledge required by the group, rather than being imposed upon the group. The excellence in leadership (EIL) framework proposed by [

2] was used in this study, which is well themed by the Asian cultural context.

Singh and Ananthanarayanan [

30] viewed organizational structure and performance from a design perspective that captures the dilemmas of business and leaders, when an equilibrium that sustains both growth and survival is projected. The concept of tensegrity, in order to create a systemic lens of looking at the organization, does away with the notion of hierarchy whilst integrating the concept of “

mandala”, the worldview framework based on dharma.

2.2. A Dharma-Driven Mandala Tensegrity EIL Framework

The EIL leadership model by [

2] identifies four behavioral dimensions: personal qualities, environmental qualities, organizational demands and managerial behaviors with an additional construct—the excellent leader. This five-construct model has been benchmarked against Asian leaders in many countries, including Cambodia [

31], China [

32], Malaysia [

33,

34], India [

11], Singapore [

35] and Thailand [

36]. These constructs are explained below (excerpted from [

37] p. 270):

Excellent leadership (EL) describes a blend of behaviors in a certain cultural setting deemed necessary for good leadership. Environmental influences (EI) are external elements that effect the organization and its accomplishment. They emphasize the significance of assessing the outer environment for prospects. Personal qualities (PQ) are the individual qualities, values, skills, and behavior. They emphasize inter-personal relationships, communication, beliefs and morality. A leader’s response to the organizational objectives, structures and issues are defined by organizational demands (OD). They emphasize the significance of organizational success. Managerial behaviors (MB) cover a leader’s managerial nature, values, attitudes and actions when dispensing managerial duties. They emphasize centralized work orientation as opposed to a participative approach.

Core assumptions of the EIL framework imply that cultural forces are omnipresent and that they shape everything that employees do, including MBs. The interrelationship of the constructs are critical in an organizational context as the perception of the Excellent Leader (EL) is ultimately driven by MB, and MB is in turn determined by external factors such as organizational demand (OD) and environmental influences (EI) together with the personal qualities (PQ) of the managers. The dynamics of the constructs are applicable in any setting and have emerged as critical to understanding implicit leadership theories (ILTs) across cultures. The EIL framework (see

Figure 1) acknowledges that cultural factors can and will often contribute to new aspects of PQ, EI and OD which impact MB and EL.

The applicability of the EIL framework has been validated across several nations. For instance, an EIL study [

36] conducted in Thailand noted that PQ was made up of the two sub-dimensions

non-confrontational style and

respect; while OD embraced admiration for authority. In Cambodia, rational decision-making underpinned by Buddhist norms was found to influence MB [

31]. In South Africa

Ubuntu has influenced PQ and EL-related perceptions [

16]. If

dharma is as universal in Sri Lanka as Confucianism is manifest in the Chinese culture, then we posit it would hypothetically influence the EIL variables. To explore this relationship further we factor in

dharma-centric ideals in the analysis.

3. The Sociocultural Environment of Sri Lanka

In this paper, we concentrate on Sri Lanka, an emerging economy at the southern tip of the Indian subcontinent with a population of 21 million, with 75 percent Singhalese who are predominantly Buddhist and 11 percent Tamils who are predominately Hindu [

38]. This nation, though strategically positioned at the bottom of the Indian subcontinent with the advantage of being a midway for shipping between the east and the west, is yet to take advantage of its geopolitical commercial importance. Instead it has been embroiled in ethnic conflicts, socialist-type reforms and centralist governments [

39]. After 27 years of one of the world’s longest and most intractable civil wars, Sri Lanka has moved towards reconciliation and a new government based on strong democratic values and the decentralization of the administration [

40]. The period after the war in 2009 was seen as a celebration of the victorious ending of a violent ethnic conflict with an estimated 70,000 deaths displacing 1 million persons [

41,

42]. As issues relating to war crimes mounted, the nation aligned with China for investment and growth, and alienated neighboring India and the West [

43]. However, this trend was reversed in 2015 after the democratic presidential election in January 2015 and the parliamentary election in August 2015. This hallmark shift promised good governance and reconciliation of ethnic differences based on equitable resources distribution and balancing traditional ties with India and the West and the new partner, China.

In understanding the preconceived notion of the world that frames Sri Lankan managerial behaviors, we provided the sociocultural environmental context within which it operates. In the following section the hypotheses are developed.

4. Dharma-Driven Variables Supporting Sustainable Leadership

In this paper, we posited that the manager as a sustainable leader will emerge to the occasion as the group need arises [

29]. In this context, the four behavioral dimensions germane to the EIL framework are applied to examine the excellence in leadership in Sri Lankan organizations. Based on the organizational context of the study, these dimensions are prioritized to support what is seen as excellence in leadership in Sri Lanka. We theorize that

Dharma, a philosophy embedded in good actions and intentions would, in the main, influence managerial and EL-related perceptions, discussing each in turn.

4.1. Managerial Behaviours

Sri Lankans, like their other Asian counterparts, are paternalistic with a strong support for family values and are more inclined to value power distance. The decision-making system in a typical Sri Lankan family extends to the work environment [

44]. The Buddhist–Hindu philosophy of dharma is pervasive and provides support to the family and community, or

sangha, as an eternal law that supports and maintains order [

7]. Both conformity and independence are intertwined within the philosophical society structure

mandala to establish order. Dharma is therefore seen as a condition that preserves when it is upheld and destroys when it is violated [

45].

As the desire to be independent is discouraged from childhood, the individual, as an employee, develops a tendency to look for approval from the hierarchy within a caring and nurturing management structure. Sri Lankans are also driven towards maintaining status and supporting security-oriented upward mobility [

46]. In addition, respect for elders, status, order and obedience are common aspects of the value orientation of Sri Lankan employees [

44,

47]. Consequently, it can be argued that Sri Lankans value a leader who displays managerial behavior that emphasizes persuasive powers within a

dharma-valued management style where the individual merges within a supportive corporate culture. The following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 1. Sri Lankan managers value a leader who supports good managerial behaviors.

4.2. Personal Qualities

In terms of national cultural values, Sri Lankans exhibit many South Asian traits in their family and other social interactions [

46,

48]. In a recent study [

49], executives in business organizations in Sri Lanka identified the family as the main influence on shaping their values—most singling out either the father or mother as exerting the most influence.

As a part of Indian civilization, the Sri Lankan culture is perceived to be preoccupied with individual psychological development when compared to natural and social developments, which are the main focus of Western civilizations [

44]. This surmise is supported by the fact that the centrality of individual psychological development is evident in both Theravada Buddhism and Hinduism, in which the roots of Sinhalese and Tamil—the two main subcultures of Sri Lanka—can be found. The concept of

dharma is central to Theravada Buddhist and Hindu philosophies, which emphasizes self-realization as the path to individual salvation. It is a belief that the effect of

karma to an individual is reduced following a virtuous path where present and past actions may either prevent or aid salvation. Karma is described in the Vedas as an individual’s indulgence in the sensory pleasures. It is the aim of every good Buddhist and Hindu to break the cycle of rebirth or to be born as a higher-order being through the actions of good karma, however accumulation of bad karma will lead to reincarnation to a lesser being. The paths to individual salvation and self-realization, however, may differ between the two religions. Theravada Buddhism places emphasis on the teachings of the Buddha with little emphasis on deity worship. Hinduism personalizes religion in the form of deity worship, where, though the concept godhead is one, the godhead takes multiple forms to emphasize human needs as avatars. To the Hindu, Buddha is worshiped as an avatar [

31]. Due to the impact of religion and its emphasis on being a good person, being family-oriented as well as being individualistic are both valued.

The Sri Lankan employees are subject to contrasting cultural forces framed within a religious-social setting of the two main Indian Subcontinent religions, Buddhism and Hinduism. Fernando and Venkataraman [

48] placed the family within the religious influence as providing the connectivity to leadership values.

4.2.1. Personal Quality—Trust

Trust has consistently been studied as a mediating factor in numerous relational leadership research studies, for example [

50,

51,

52]. Bartram and Casimir [

50] found that transformational leadership can improve the performance in environments with high levels of control, such as in call-centers, by empowering followers and by building trust in the leader. In the relational leadership model proposed by [

51], leader–follower relationship is developed through personal interactions in which parties evaluate the integrity, ability and benevolence of each other. The context of the relationship in both the studies [

50,

51] is based on interpersonal trust. In an EIL regional study [

52], trust in others was one of four leadership dimensions (the others dimensions being consideration for others, progressive stability and strategic thinking) that provided explanation on what managers in the Association of South East Nations (ASEAN) perceive to be important for leaders to have.

In a cultural context, [

53] found evidence that Australian followers recounted higher levels of trust in their leaders as opposed to Chinese followers. Thus, culture influenced the effects of trust on the leadership–performance relationship. The authors of [

53] are of the view that the findings demand the necessity to weigh cultural setting within which leadership occurs in understanding mediated relationships with performance and achievements. An EIL study on Indonesia [

54] confirmed the importance of trust within an authority-based leadership structure in Indonesia [

55] where the manager and the employee are expected to be trust-worthy and obliged within a dependency-based relational framework. Based on the importance of trust in a relational leadership, the importance of trust is also tested in this study.

Hypothesis 2. Sri Lankan managers value a leader who places importance on trust in pursuing excellence in leadership.

4.2.2. Personal Quality—Morality

Morality has been constructed as a positive influence on leadership behaviors [

56,

57,

58]. Though the authors of [

48] supported religion as an influencer of family values, they did not see religion as a dominant factor in determining personal values. However, an EIL study [

16], demonstrated that where morality is based on religious and ethnic values, it can contribute to unethical behaviors such as during the apartheid times in South Africa. Morality in such situations can be seen as a differentiating rather than a uniting influence for managerial performance. Given Sri Lanka’s recent civil war, morality may again be perceived as having an adverse impact on excellence in leadership in Sri Lanka. Therefore, the conditions under which morality operates as a contributor to excelling in leadership is of interest in this paper. Based on this interest, the following hypothesis is tested.

Hypothesis 3. Morality impacts negatively on what constitutes excellence in leadership in Sri Lankan organizations.

4.2.3. Environmental Influences

Sri Lankan managers are said to be fatalistic, a characteristic that could impact vision [

44,

47], or be seen as an antithesis of dharma, a characteristic that could impede the development of the nation as a strategically important island nation in the Indian Ocean, making it less likely to be concerned about the external environment. However, in recent years Sri Lankans have been internationally exposed as a consequence of the protracted civil war [

49]. The war has created an extensive Sri Lankan diaspora providing an “external economy”; and now aided by professional management education emphasizing strategic orientation [

59]. As a consequence of the civil war and Sri Lanka’s distancing from its traditional trade partners in the West and India, China has increasingly filled this void [

60]. The Sri Lankan community’s involvement in external influences impacting on their wellbeing and development has thus been enhanced, especially given that the USA, India and China are now competing to establish influence in Sri Lanka [

61]. Consequently, it can be argued that Sri Lankans value a leader who displays knowledge of environmental influences and that emphasizes the significance of assessing and evaluating the external environment for long-term continuity. Thus, the following hypothesis is advanced in this paper.

Hypothesis 4. Sri Lankan managers value a leader who supports environment influences impacting sustainability.

4.2.4. Organizational Demands—the Nurtured Organization

In this paper, we posit that there are demands expected within an organizational performance framework whilst cultural and social influences impact on these demands. These demand–impact relationships are viewed as tensions. The metaphor of tension contributes to the dynamic nature of the current model, where the leader seeks tensegrity, defined as “the pattern that results when push and pull have a win–win relationship with each other” [

30] (p. 10). This view is adopted in this paper and explained by the dharma-driven tensegrity mandala. Within the tensegrity mandala, “shadow” or consequent pathos [

30] (p. 96) is viewed in this paper as

dharma sankata or dilemmas that leaders have to address. The tasks of managers as leaders in organizations is to understand these demands, as well as impacts placed on these demands, both positive and negative, address them and motivate employees towards performance.

We therefore propose that a nurtured organization supportive of a shared vision and inclusivity would be supported by Sri Lankan managers.

Hypothesis 5. Sri Lankan managers value a leader who supports the nurtured organization

The authors of [

62] asserted that due to the influence of Protestant work values, the effect of the middle path—the key tenet of Buddhist philosophy—cannot be expected to be as strong as it should be in a culture influenced only by Theravada Buddhism. Therefore, given that Sri Lankans have been exposed to Protestant ethics (see also [

62]) and materialistic pursuits, their managers are likely to value their own prosperity and that of the organization, and thus managerial behavior and organizational demands can be anticipated to be more important determinants of excellence in leadership than personal qualities and environmental influences. Thus, the following hypothesis is advanced in this paper:

Hypothesis 6. Sri Lankan managers, due the influence of Protestant work values, would prioritize managerial behaviors and organizational demands in line with material pursuits.

In this study, we also propose that variations in cultural values among Sri Lankans is more prevalent among those who were born after 1977 when the country began to experience significant changes in its economic, political and, later, social landscape [

63]. While Sri Lanka witnessed liberalization of its economy after 1977, the country went through a second wave of privatization in the late 1980s and mid-1990s [

64]. In addition, individuals who were born after 1977 lived entirely or most of their lives in a period of armed conflict. These dynamics can be expected to influence leadership values, and thus managers below 35 years of age when the data were collected for this study (in 2013/2014) can be expected to be different in terms of leadership values. Thus, the following hypothesis is advanced in this paper:

Hypothesis 7. Sri Lankan managers below 35 years of age in 2013/2014 value a leader who prioritizes organizational demands, managerial behaviors, personal qualities and environmental influences differently to those who were over 35 years of age in 2013/2014.

Just as Sinhalese culture cannot be explained through Buddhism alone, Tamil culture also cannot only be understood through Hinduism. Like the Sinhalese culture, Tamil culture has been influenced by various forces including colonization, economic liberalization and, finally, the recently concluded armed conflict. While some [

65] have argued that the influence of colonization on the Tamil culture was not as strong as its influences on Sinhalese culture, it is widely believed that it has been strongly influenced by South Indian culture.

The authors of [

66] believed that while the missionary influence during the colonial period may have resulted in some changes in Tamil culture, the missionary influence on Tamil culture was not as great as its influence on the Sinhalese. They indicated that even though some important changes took place during the European occupation, the caste-based social hierarchy, one of the important aspects of Tamil society, was not questioned.

However, Madavan [

66] has pointed out the Liberation Tamil Tigers of Eelam (LTTE) removed all caste-related distinctions that traditionally determine the choice of a spouse and an individual’s social networks, and made caste a taboo subject. The LTTE, a militant group, fought for a separate state in the North and North East regions occupied by Tamil inhabitants between 1976 and 2009. Madavan further stated that even if many members of the older community had to put aside caste distinctions publicly due to pressure from the LTTE, some elderly Tamils still covertly maintained the caste system in which they have been raised [

66]. Nevertheless, on the whole, the emphasis on the distinction between high and low caste Tamils seems to be less than it was before the ethnic armed conflict.

It should be noted that scholastic work on the impact of cultural values on work, especially related to Tamil values, has been limited due to the armed conflict that prevailed in the Jaffna Peninsula and in most parts of the eastern Tamil-dominated areas [

67]. The armed conflict that continued for almost three decades prevented most researchers from undertaking empirical work, and the limited research that was undertaken was mainly on issues related to ethnicity or nationalism [

59]. Therefore, any discussion to date on Tamil culture in Sri Lanka has been more conceptual than empirical.

Recognizing the difference in ethnic development of the Singhalese and Tamils in Sri Lanka, the following hypothesis is advanced in this paper:

Hypothesis 8. There are differences in the managers’ perceptions of what constitutes excellence in leadership between the Singhalese and Tamil managers in Sri Lankan organizations.

5. Research Methodology

This study’s survey was carried out using the 94-statement excellence in leadership (EIL) questionnaire developed by [

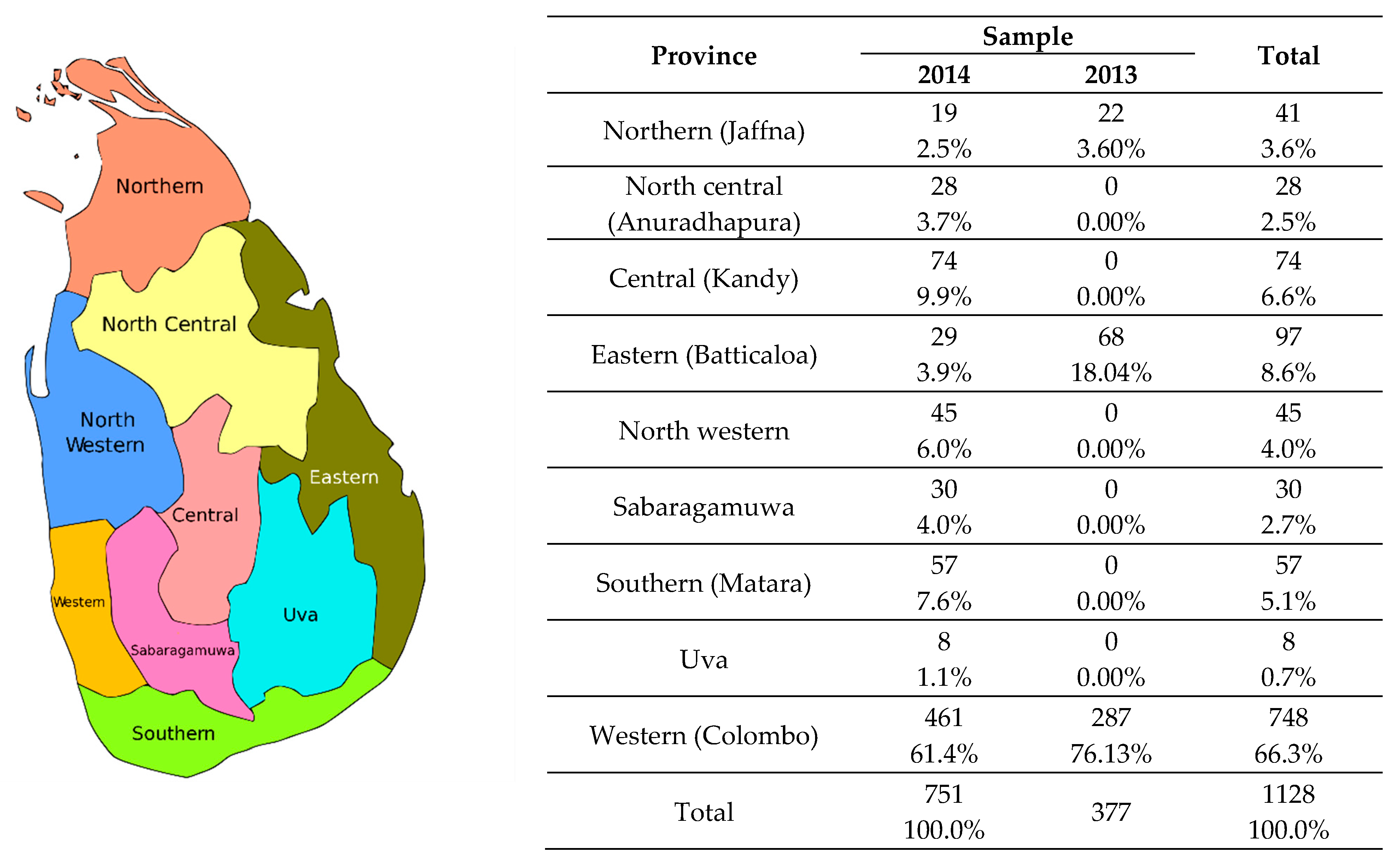

2]. The Postgraduate and Mid-Career Development Unit of the University of Colombo facilitated the project. After approval from participating universities in Sri Lanka, questionnaires were administered to working managers enrolled in master programs, and 1140 useful responses were received. The questionnaires were sent in two batches: the first batch of 500 was sent in June 2013 with an effective return of 377 responses; and the second batch of 1632 was sent in 2014 with an effective return of 751 responses. The 2013 and 2014 samples markedly differed in terms of location, industry, language, religion and size. However, the gender and age distributions were similar. Perceptions of managers’ excellence in leadership and their demographic data were collected employing the 94-statement questionnaire with a scale of 1 representing “no importance” and 5 “great importance”.

Multivariate analysis such as exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were carried out on the leadership criteria to establish the measurement models for EL, PQ, MB, OD and EI (detailed results are in the

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3,

Table A4 and

Table A5 in the

Appendix A). The EFA suggested 1-dimensional constructs in all cases except PQ, while the CFA indicated a good fit for all the measurement models according to criteria defined by [

68]. The weights of these models were compared based on ethnicity, gender, location and age, and were found to be similar in all cases.

Scales were established for the constructs and they were tested for reliability using Cronbach’s alpha. A general linear model was employed to analyze the effects of demographic variables on these scales and a regression analysis was used to construct a structural equation model for leadership excellence. The weights of the models were compared for managers under and over 35 years of age at the time of response.

6. Results

An effective return sample of 1128 managers was received from 2132 questionnaires distributed, providing an effective return rate of 53 percent.

Figure 2 below highlights survey responses by the regions of Sri Lanka. The questionnaires were distributed in the two 2013 and 2014 timeframes in batches of 500 and 1632 questionnaires, respectively, for three main reasons. Firstly, the country had only ended its armed conflict in 2009, and access to many areas was still difficult, thus the first batch was mainly collected in the Colombo region. Secondly, based on the success of the first batch collection, a second batch to be collected across the country was arranged for a doctoral study. In the 2014 batch, 11 extra questions were added to the questionnaire as part of a doctoral study, but are not included in this paper. Of the 1632 distributed questionnaires, 1332 were face-to-face and 300 by postal survey. Thirdly, it was also considered opportune to reduce common method bias issues by using two timeframes [

69,

70].

The demographic analysis shows that the majority of this study’s managers (83%) spoke Sinhala, while the other 17 percent spoke Tamil. In addition, most managers (72%) were of the Buddhist religion, followed by 11 percent Hindu, 11 percent Christian and 4 percent Islamic. All regions contributed respondents, with the majority from the Western province including Colombo. The majority of respondents (71%) were in the private sector, with 24 percent in government positions and 5 percent in NGOs. Women were in the minority (30%), and the majority of managers were aged under 50 years: 59 percent under 35 years, 78 percent under 40 years, 90 percent under 45 years, and 94 percent under 50 years. Middle managers had the highest representation (53%), followed by 21 percent line managers and 26 percent senior managers. Most respondents (75%) were working in organizations with more than 100 employees, with 40 percent employed in organizations with over 1000 employees. There was also variation in department size: 78 percent were in departments with less than 50 employees; 11 percent in departments with between 50 and 100 employees; and 11 percent in departments with over 100 employees.

As depicted in the

Appendix A, CFA produced good models for the measurement of EL, EI, OD, PQ and MB. In this study, PQ split into two factors: trust and morality. In consideration of the variables that loaded in each factor, OD was renamed “nurtured organization” MB as “good management”, and EI as “sustainability”. The results in

Table 1 show that all the resulting scales except perhaps Morality had reasonable reliability (Cronbach alpha > 0.70). In addition, all the correlations in

Table 2 are significant at the 0.1% level.

Regression analysis and structural modeling addressing hypotheses 1–6 were used to describe leadership excellence in terms of sustainability (EI), nurtured organization (OD), trust (PQ), morality (PQ) and good management (MB), and an invariance test was used to determine whether the relative importance of the weights differed significantly across gender, language and age addressing Hypothesis 7 in particular. Finally, regression and MANOVA analyses were used to investigate differences between the Sinhalese and Tamil groups, addressing Hypothesis 8.

6.1. Combined Sample

The regression analysis in

Table 3 suggests that trust is the most important predictor of leadership excellence, with nurtured organization also being relatively important. Although good management and sustainability are less important, these variables are still identified as significant, suggesting a direct impact on leadership excellence. However, of greatest interest is the negative relationship between morality and Excellent Leader when the other variables are controlled.

Figure 3 shows a saturated structural model illustrating the

Table 3 regression model. This model explains 57 percent of the variation in the importance of leadership excellence, providing support for hypotheses 1 to 6.

The darker lines in

Figure 3 suggest that PQ:trust and EI:sustainability underlie nurtured organization, and that all three of these characteristics are regarded as critical for good management.

Table 4 below shows that, contrary to expectation, trust is significantly more important than the other predictors of EL:leadership excellence, and EI:sustainability is also significantly more important than MB:good management behavior.

The structural model was supported by the 2013 data (Chi-squared = 2.504, df = 1, p = 0.114) and the 2014 data (Chi-squared = 1.582, df = 1, p = 0.208), with similar standardized effect sizes obtained for the 2013 and 2014 data samples, despite their very different characteristics.

When this model was compared by gender, no significant differences were found (Chi-squared = 15.519, df = 13, p = 0.276). Similarly, no significant differences were found for Sinhalese versus Tamil managers (Chi-squared = 15.926, df = 13, p = 0.253), or for managers under the age of 35 versus over the age of 35 (Chi-squared = 21.659, df = 13, p = 0.061). Therefore, the results suggest that neither gender, ethnicity nor age influence the perceptions of Sri Lankan managers as to what constitutes excellence in organizational leadership.

However, close examination of the weights for the EIL constructs shown in the

Appendix A indicate some interesting differences between Singhalese and Tamil managers. Considering significant differences in the weights it seems that Tamil managers value the following more than Sinhalese managers:

while Singhalese managers value the following more than Tamil managers:

OD: Nurtured Organization—adjust organizational structures and rules to the realities of practice;

PQ: Trust—accept that others will make mistakes;

PQ: Morality—follow the heart and not the head in compassionate matters.

This suggests that the Tamils of Sri Lanka are more concerned with good management where consistency in decision-making and judging competence are valued. The Singhalese value a nurturing organization that is able to address the realities of business practice whilst accepting mistakes will be made and being compassionate.

Finally, the effects of demographic characteristics in regard to mean importance levels were also tested with a MANOVA analysis and follow-up ANOVA tests.

6.2. MANOVA Analysis

As shown in

Table 5, the final MANOVA analysis found significant mean differences for both industry and ethnic groups; however, the effect size associated with these differences was small. Follow-up ANOVA tests showed that only in the case of morality were there significant differences (F(2,1023) = 18.39,

p = < 0.001, η

2 = 0.035) between the ethnic groups; and that only in relation to trust was there a significant industry sector effect (F(2,1023) = 6.139,

p = 0.002, η

2 = 0.012). The marginal mean for morality for Sinhalese managers (MN = 3.26) was significantly lower than that of Tamils (MN = 3.61) and the other respondents (MN = 3.71), while government-employed managers found trust to be significantly less important (MN = 4.02) than NGO managers (MN = 4.30). Private sector managers’ responses sit between these two groups (MN = 4.16).

These tests, as do some of the weights in the measurement models for the Excellent Leader constructs, support some difference in ethnic influence, and therefore indicate support for Hypothesis 9. This finding should, however, be interpreted as having only marginal importance, as the Singhalese and Tamil managers view morality as having an overall negative effect on Excellent Leader. The hypothesis that age acts as a differentiator in the perceptions of what constitutes excellence in Sri Lankan organizational leadership is not supported; thus, Hypothesis 8 is rejected. The rejection of this hypothesis may be due to the period of uncertainty that prevailed in the last three decades with the civil war affecting the population generally. However, as highlighted in

Table 5, though not hypothesized, perceptions by the industry sector with regard to trust are evidenced as a differentiator to what constitutes excellence in leadership in Sri Lankan organizations.

In summary, there was no significant difference between Tamils and Sinhalese in terms of the weights for the structural model. For both groups, higher morality scores were associated with lower Excellent Leader scores when the other aspects of leadership were controlled, suggesting that managers who considered morality to be more important considered excellent leadership to be less important. However, the MANOVA analysis showed significant differences between these two groups in terms of mean morality levels. Morality was considered to be significantly less important by the Sinhalese managers than the Tamil managers. The implications of these results will be discussed in the next section.

7. Discussion

The original thrust of this paper, that leadership is a complex phenomenon, becomes even more pronounced when we see through the lenses of sustainability [

71]. Thus, in seeking corporate sustainability and what constitutes excellence in managerial leadership in Sri Lankan organizations, [

71] (p. 369) suggests “organizations are complex adaptive systems operating within wider complex adaptive systems,” therefore, fine-grain analysis to ascertain in what ways an organization is to be sustainable and what demands are placed on leaders becomes crucial. Leaders and leadership are, therefore, seen as the key conduit through which organizational sustainability connects to the wider system. In this research, our focus was on the Sri Lankan managerial leadership profile and the subcultural influences that make organizations sustainable. In essence, we studied the cultural factors such as religious affiliations, ethnicity, gender, age and managerial levels that influence leadership values and sustainability of the organization.

Based on structural modeling (

Figure 3), six specific constructs framed excellence in leadership in Sri Lankan organizations. Hypotheses one to five were found to be in support of the model (

Table 6), while hypotheses six to eight reflected demographic and social values and these are discussed below.

The findings suggest that in Sri Lanka—a nation that has been divided by prolonged ethnic conflict—values based on ethnicity and religion have little impact on what constitutes leadership excellence in organizations. The findings highlight three sustainability-related perspectives of excellence. In the first instance, this study supports a nurturing organization; second, the values contributing to good management; and thirdly the values that support what constitutes excellent leaders in Sri Lankan organizations. These three perspectives, which were presented in

Figure 3, will be discussed below.

7.1. Nurtured Organisation

A nurturing culture within organizational settings has been explored in the extant literature, especially in Eastern literature [

2,

11,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

72,

73,

74]. A nurturing viewpoint within organizations is seen as providing a paternalistic leadership structure and thus inconsistent with a Western viewpoint [

75].

In this study, we argued that a systemic view based on a symbiotic relationship between the organization and the individual exists, a viewpoint supported by Sen [

76] in sustainable human capacity building. In this paper, this is driven by a dharma-based mandala or worldview. The organization is thus seen as caring and supporting of pastoral needs and seeking a win–win position (for details and statistical support see

Table A3 in the

Appendix A). This paper thus supports the view that for good management in Sri Lankan organizations, the nurturing of organizational values, such as supporting joint decisions (β = 0.644), being adaptable (β = 0.631), belonging or acting as a team (β = 0.609) and sharing power (β = 0.456) are highly valued. The managers have also supported the view that sustainability factors, such as being socially and environmentally responsible (β = 0.683) and supporting social trends that impacts work (β = 0.649) and trust, such as respect for the self-esteem of others (β = 0.683), are factors that strengthen the nurturing capacity as it influences good management practices in the organizations (for details and statistical support see

Table A2 in the

Appendix A). The organizational demands supporting a nurtured organization are perceived as:

Support decisions made by others

Be adaptable

Act as a member of a team

Focus on maximizing productivity

Adjust organizational structures and rules to realities of practice

Share power

Sell the professional or corporate image to the public

Give priority to long-term goals

Though both the Singhalese and Tamils support the nurtured organization, the Singhalese value more an organizational structure that adapts to the realities of practice. The Singhalese have also expressed that they value a nurtured organization that is trust-based (for details and statistical support see

Table A4 in the

Appendix A) and accepts that people will make mistakes (β = 0.596) and is also guided by moral values (β = 0.596) that are compassionate in nature.

7.2. Good Management

The empirical evidence from this research strongly supports the view that in order to have good management, trust from employees (η

2 = 0.36,

p = 0.001) and a nurturing organization (η

2 = 0.34,

p = 0.001) are essential components. The managers have further stated that issues relating to sustainability (η

2 = 0.41,

p = 0.001) and trust (η

2 = 0.47,

p = 0.001) inform nurtured organizations. There is therefore clear prioritization of organizational factors that are perceived to support good management (for details and statistical support see

Table A5 in the

Appendix A). The perceived managerial behaviors supporting good management are perceived as:

Think about the specific details of any particular problem

Listen to and understand the problems of others

Use initiative and take risks

Trust those to whom work is delegated

Be objective when dealing with work conflicts

Consider suggestions made by employees

Persuade others to do things

Be consistent in making decisions

Focus on the task at hand

Keep up-to-date on management literature

Select work wisely to avoid overload

Be strict in judging the competence of employees

Again, both the Singhalese and Tamils have supported good management as a measure of excellence in leadership in Sri Lankan organizations. However, fine-grained analysis highlights the Tamils favoring consistency in decision-making (β = 0.764) and competence of employees (β = 0.723) as a more important gauge of good management compared to the Singhalese (β = 0.535 and β = 0.427, respectively). This affirms Hypothesis 8.

The view presented in support of these organizational factors is similar to [

77], where they conclude in their research that successful identities of a leader within an organizational culture is achieved when personal identity is forgone in the interest of the organizational identity or where “personal identities are subsumed within professional identity” (p. 185). Both Tamil and Sinhalese communities collectively agree that “Think about the specific details of any particular problem” (β = 0.644) and “Listen to and understand the problems of others” (β = 0.627) are most important, suggesting that problem solving is the most important managerial behavior for good management. Yet even though these two main Sri Lankan communities collectively support the overall measures, the Singhalese next prioritize “Think about the specific details of any particular problem” (β = 0.656) and “Use initiative and take risks” (β = 0.618), while the Tamils prioritize “Be consistent in making decisions”(β = 0.764) and “Be strict in judging the competence of employees” (β = 0.723). Based on these findings, the Sinhalese manager is deemed as attaching more importance to problem solving and action-oriented management, while the Tamil manager is viewed as more focused on consistency in decision-making and seeking competency in employee actions.

7.3. Excellent Leadership

Ferdig [

78] suggested that co-creating a sustainable corporate leadership future meant finding the balance between complex interlinked livings systems. To put this in practice, the data in this study suggested support for Sri Lankan managers to prioritize all components of excellent leadership—a nurtured organization, sustainability, trust, good management and morality—with significant coefficients between these components and the Excellent Leader scale. To be an excellent leader in Sri Lankan organizations, the managers perceive that nurtured organization partially mediates between what constitutes good management and organizational sustainability and trust. Sustainability (η

2 = 0.41,

p = 0.001) and trust (η

2 = 0.47,

p = 0.001) have a strong and positive influence on nurtured organization, while trust (η

2 = 0.36,

p = 0.001) and nurtured organization (η

2 = 0.34,

p = 0.001) also influence good management directly. Therefore, the practice of good management in Sri Lankan organizations requires both trust and what constitutes a nurtured organization. Trust and sustainability are closely associated and influence each other (η

2 = 0.67,

p = 0.001). These two components are the bedrock of the excellence in leadership framework for Sri Lankan organizations, both from the perspectives of good management and being an excellent leader. Therefore, both sustainability (EI) and trust (PQ) are perceived to directly influence what constitutes excellent leadership in Sri Lankan organizations, as well as mediated through nurtured organization and good management practices.

This study also informs that in the case of trust, there is a significant industry effect, where the managers from NGOs perceive trust more importantly than the private and public sector managers. These findings support the view that NGOs are civic society groups that are community service-oriented and therefore perceive trust as an important component of leadership excellence. The least supportive of trust are managers from the public sector.

An interesting finding reported here is the value of morality that has surfaced as a mediating influence on the value of an Excellent Leader. The study highlights morality (α = 0.641) as being valued by both the Tamils and the Sinhalese; however, it also has a negative influence (η2 = −0.09, p = 0.001) on the perception of what constitutes an excellent leader in Sri Lankan organizations. In an organizational context, both communities do not believe that religious beliefs (β = 0.517), self-morality (β = 0.650) or decisions made through emotive actions (β = 0.694) would contribute to being an excellent leader. Therefore, in the Sri Lankan context, the organizational manager as leader is deemed as impartial to religious influences and personal moral views, and acts with reason.

The excellent leader in Sri Lankan organizations is perceived by managers as a person who prioritizes work (for details and statistical support see

Table A1 in the

Appendix A). The excellent leader is therefore perceived as an individual who:

Can organize work time effectively (β = 0.791);

Motivates employees (β = 0.737);

Has a strategic vision for the organization (β = 0.644);

Has confidence in dealing with work and with people (β = 0.640);

Is honest (β = 0.617);

Continues to learn how to improve performance (β = 0.589).

These above overall measures inform the expectations of excellence in a leader. The manager who can organize work time effectively is seen as the most important measure of what an excellent leader is. Though the Tamil and Sinhalese groups prioritized the measures differently, the measures are sufficiently close for this to be regarded as a consistent perception in Sri Lanka (see

Appendix A,

Table A1).

This study, similar to [

79], suggests that including sustainability adds capacity building and a new mindset to include a greater expanse of stakeholders and viewpoints as opposed to purely being organizational oriented. Thus, the empirical research, conducted through managers engaged in the private, public and NGO sectors, provides the framework for understanding sustainable leadership practices in Sri Lankan organizations. The findings suggest that there are no significant differences based on ethnicity and religion, implying that the cultural differences between Tamils and Sinhalese are not based on these two factors in relation to Sri Lankan managers. This affirms Hypothesis 6 was not supported. The findings also do not support Hypothesis 7, given that similar views of excellence in leadership were found among the pre and post war generations. This suggests that the observed differences during Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict, considered to be based on religious and ethnicity, have not been reflected in the organizations studied.

8. Implications of the Study

Building from the aforementioned viewpoint, it warrants to question the theoretical development and implications for research, especially for foreigners who want to engage with Sri Lankan managers at a practical level. The findings of this paper shed some light on the theory and practice of managerial leadership in Sri Lanka. Firstly, this study highlights the awareness of cultural dimensions in Sri Lanka and notes a fusion of cultural values within organizations. The identification of ethnic differences as weak determinants of managerial values in organizations in Sri Lanka is evident. Ethnic and religious associations have negligible bearing on managerial leadership behavior and are relatively unimportant to leadership excellence in Sri Lankan organizations. Therefore, religious and cultural values, though important to each community, do not appear to influence managerial behaviors in Sri Lankan organizations. Could this be based on Buddhism and Hinduism being viewed as passive and highly personalized religions as both are founded on the concept of dharma or virtuous acts emphasizing personalized relationships? These influences should be explored in future studies.

Secondly, the thrust of this study supports a paradigm shift, at least in a theoretical sense, from exploring leader–member relations to a much broader perspective of integrating the whole organizational environment in leadership decision-making. In this research, sustainability and trust have emerged as important components of excellent leadership in Sri Lankan organizations. These findings extend previous research where organizational transformation has been identified as requiring sustainability measures for sound business decisions, for example [

71,

80,

81,

82], and where trust has been deemed an important factor for good leadership, for example [

82,

83,

84]. There are, however, very few studies that have provided empirical evidence to support sustainability as a factor contributing to leadership excellence in an organizational cultural context in Asia. In this study, while sustainability has been shown to have a significant and positive relationship with Excellent Leader (β = 0.18), it appears to have a much stronger influence on nurtured organization (β = 0.41) and good management (β = 0.27).

Both the Singhalese and Tamils have started looking outwards and engaging with the international economy and are acutely aware of prevailing local conditions. The Tamil population, both during and after the ethnic conflict, has been cautious about engaging with the wider Sri Lankan economy, particularly as economic and political conditions deteriorated during the period of the conflict. The Sinhalese population’s approach, during the same period, has been one of strengthening the resolve of a war situation, which adversely impacted on all communities. These influences are emic in nature, which is a view supported by [

59], as having a greater weight on Sri Lankan behaviors than the etic approach supported by behavioral theorists, for example [

43].

Thirdly, a unique finding in this study is the inverted relationship of morality to leadership. Morality has been studied extensively and most of the research has supported a positive relationship to leadership behaviors (e.g., [

34,

57,

85]). However, the authors of [

16] contended that it often has a negative influence on excellent leadership, with their findings—similar to this study—suggesting that a situation where morality is based on religious and ethnic values can contribute to unethical behaviors, such as during the apartheid regime in South Africa, effectively presenting a divisive factor to harmonious relations. In a sense, morality arising out of a religious and ethnic value base can be parochial and inward looking and thus divisive. In effect, morality is viewed as an antithesis to

dharma and to the maintenance of balance in the

mandala within the Sri Lankan organizational context.

Fourthly, from the post-ethnic conflict period in Sri Lanka, this study clearly suggests that ethnicity and religion have little impact on work relationships. With regard to the belief systems between the Sinhalese and Tamil, there are more similarities than differences. However, it is important for foreigners engaging with Sri Lankan managers to recognize subtle cultural behavior differences of the two main communities in Sri Lanka.

These findings, which suggest that in an organizational context ethnicity and religion are not important factors for performance, while sustainability and trust are, should be emulated for the national development of Sri Lanka.

From a theoretical development point of view, this study emphasizes that developing merely universal cultural dimensions to measure national values excludes emic measures or specific values unique to a nation. This study, similar to other studies of Selvarajah and colleagues [

11,

16,

31,

35,

36,

37,

54] has adopted what [

86] underlined as the need for establishing culturally-based theories which are bound to an environment.

The propositions in this study are built on the cultural constructs contributing to leadership excellence, and are bound to the cultural values in Sri Lankan organizations. Therefore, the hypotheses holding the EIL model address societal values that have undergone an intense period of ethnic conflict. The politics and lack of commercial development in disaffected regions of Sri Lanka seem to have supported the perceptions of the respondents. This study has made it clear that the perceptions of ethnicity and religions are not dividing factors in Sri Lankan organizations. Therefore, if the result reported in this paper is to be emulated for national development, the emphasis by the government on reconciliation has to place less emphasis on ethnicity and religion and more on equitable resources allocation across Sri Lanka. In this sense, the 27 years-long ethnic struggle in Sri Lanka was perhaps more a result of uneven economic and political resources distribution to the regions rather than a crisis brought about purely by ethnicity differences.

9. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are some limitations in this study worth noting. The exploratory nature of the study and the smaller sample size do not warrant any creation of purposeful causal relationships. However, the effects of ethnicity on the study ought to be probed further.

An assessments of importance on the 94 items of leadership excellence would have introduced common variance bias to the results. However, as revealed by [

87], the impact would be insignificant due to CFA models applied to 24 multimethod–multitrait correlation matrices. In addition, the authors of [

88] noted that multivariate linear relationships show that common method bias generally reduces in a regression equation when additional independent variables having common method variance are involved. Here, there are five leadership constructs that were tested together, suggesting that common method variance has been considered in the analysis. Further, the similarity of the structural models fitted for the 2013 and 2014 samples, despite some differing demographic characteristics, suggests that the results have predictive validity. As previously mentioned, the collection of data in two separate periods and the second data collection questionnaire having additional questions further reduced common method bias issues [

69,

70].

Undeniably the research design could have been built around objectively measuring leadership excellence as the dependent variable. However, this is not straightforward, and even well-cited studies such as House’s GLOBE study have failed to achieve this (see [

89,

90]).

Although this study attempted to include representative population samples from across the country, the data gathering was mainly concentrated in Colombo. The effects of the ethnic conflict are more relative to the Northern and Eastern parts of the country, and future studies should provide more effective samples from these regions. The Sinhalese ethnic group comprised 72 percent of the sample, with Tamil represented by only 11 percent of the surveyed managers. Though this is somewhat representative of the population, a larger sample size for the Tamils is suggested for future research. Future studies should also be conducted with a larger sample size, exhibiting greater balance in terms of location and age for each of the ethnic groups.

This study is based on the perceptions of managers on leadership in Sri Lankan organizations as the context. Therefore, in studying sustainability and leadership, the findings are specific to that environment and as such should not be generalizable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.; methodology, C.S. and D.M.; software, S.S.; validation, C.S., D.M. and S.S.; formal analysis, C.S., D.M. and S.S.; investigation, C.S., D.M. and S.S.; resources, C.S. and J.J.; data curation, D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.; writing—review and editing, C.S., D.M. and S.S.; visualization, C.S. and S.S.; supervision, C.S.; project administration, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the University of Colombo for providing the ethics clearance to J.A.S.K Jayakody, and the Swinburne University of Technology (SUHREC 2013/292) for the data collection conducted in Sri Lanka. We wish to also thank the Research Center at the Postgraduate Institute of Management, the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, for assisting in the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Excellent Leader [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha = 0.829)]. (Normed Chi-Square = 1.921, GFI = 0.995, AGFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.994, CFI = 0.996, RMSEA = 0.028).

Table A1.

Excellent Leader [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha = 0.829)]. (Normed Chi-Square = 1.921, GFI = 0.995, AGFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.994, CFI = 0.996, RMSEA = 0.028).

| | Overall | Sinhalese Buddhist | Tamil Hindu |

|---|

| Organise work time effectively | 0.791 | 0.786 | 0.749 |

| Motivate employees | 0.737 | 0.745 | 0.674 |

| Have a strategic vision for the organisation | 0.644 | 0.639 | 0.703 |

| Have confidence in dealing with work and with people | 0.640 | 0.640 | 0.736 |

| Be honest | 0.617 | 0.588 | 0.729 |

| Continue to learn how to improve performance | 0.589 | 0.568 | 0.561 |

Table A2.

EI: Sustainability [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha = 0.785)]. (Normed Chi-Square = 1.876, GFI =0.995, AGFI =0.989, TLI=0.992, CFI = 0.995, RMSEA = 0.028).

Table A2.

EI: Sustainability [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha = 0.785)]. (Normed Chi-Square = 1.876, GFI =0.995, AGFI =0.989, TLI=0.992, CFI = 0.995, RMSEA = 0.028).

| | Overall | Sinhalese Buddhist | Tamil Hindu |

|---|

| Be socially and environmentally responsible | 0.683 | 0.694 | 0.750 |

| Identify social trends which may have an impact on work | 0.649 | 0.609 | 0.752 |

| Check constantly for problems and opportunities | 0.618 | 0.599 | 0.773 |

| Have a multicultural orientation and approach | 0.608 | 0.598 | 0.689 |

| Study laws and regulations which may have an impact on work | 0.588 | 0.596 | 0.663 |

| Use economic indicators for planning purposes | 0.566 | 0.539 | 0.683 |

Table A3.

OD: Nurtured Organisation [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha = 0.753)]. (Normed Chi-Square = 2.596, GFI = 0.988, AGFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.971, CFI = 0.979, RMSEA = 0.037).

Table A3.

OD: Nurtured Organisation [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha = 0.753)]. (Normed Chi-Square = 2.596, GFI = 0.988, AGFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.971, CFI = 0.979, RMSEA = 0.037).

| | Overall | Sinhalese Buddhist | Tamil Hindu |

|---|

| Support decisions made jointly by others | 0.644 | 0.625 | 0.743 |

| Be adaptable | 0.631 | 0.627 | 0.661 |

| Act as a member of a team | 0.609 | 0.599 | 0.643 |

| Focus on maximising productivity | 0.561 | 0.570 | 0.658 |

| Adjust organisational structures and rules to realities of practice | 0.518 | 0.585 | 0.262 |

| Share power | 0.456 | 0.450 | 0.468 |

| Sell the professional or corporate image to the public | 0.449 | 0.442 | 0.398 |

| Give priority to long-term goals | 0.403 | 0.398 | 0.457 |

Table A4.

PQ: Trust / Morality [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha=0.808 for Trust, alpha = 0.641 for Morality)] (Normed Chi-Square = 1.733, GFI = 0.960, AGFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.900, CFI = 0.918, RMSEA = 0.045).

Table A4.

PQ: Trust / Morality [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha=0.808 for Trust, alpha = 0.641 for Morality)] (Normed Chi-Square = 1.733, GFI = 0.960, AGFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.900, CFI = 0.918, RMSEA = 0.045).

| | Overall | Sinhalese Buddhist | Tamil Hindu |

|---|

| Trust | | | |

| Respect the self-esteem of others | 0.641 | 0.622 | 0.702 |

| be an initiator | 0.590 | 0.603 | 0.670 |

| Speak clearly and concisely | 0.589 | 0.674 | 0.702 |

| be practical | 0.518 | 0.662 | 0.626 |

| Accept responsibility for my mistakes | 0.496 | 0.492 | 0.372 |

| Accept that others will make mistakes | 0.449 | 0.596 | 0.304 |

| Deal calmly in tense situations | 0.436 | 0.625 | 0.598 |

| Be consistent in dealing with people | 0.291 | 0.555 | 0.615 |

| MoralityFollow the heart not the head in compassionate matters | 0.694 | 0.720 | 0.551 |

| Follow what is morally right, not what is right for self or organisation | 0.650 | 0.627 | 0.613 |

| Behave in accordance with your religious beliefs | 0.517 | 0.503 | 0.609 |

Table A5.

MB: Good management [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha = 0.845)] (Normed Chi-Square = 1.815, GFI = 0.952, AGFI = 0.934, TLI = 0.918, CFI = 0.930, RMSEA = 0.040).

Table A5.

MB: Good management [Standardised (Beta) Weights (alpha = 0.845)] (Normed Chi-Square = 1.815, GFI = 0.952, AGFI = 0.934, TLI = 0.918, CFI = 0.930, RMSEA = 0.040).

| | Overall | Sinhalese Buddhist | Tamil Hindu |

|---|

| Think about the specific details of any particular problem | 0.644 | 0.656 | 0.693 |

| Listen to and understand the problems of others | 0.627 | 0.591 | 0.686 |

| Use initiative and take risks | 0.603 | 0.618 | 0.680 |

| Trust those to whom work is delegated | 0.593 | 0.590 | 0.696 |

| Be objective when dealing with work conflicts | 0.592 | 0.570 | 0.701 |

| Consider suggestions made by employees | 0.586 | 0.575 | 0.560 |

| Persuade others to do things | 0.585 | 0.569 | 0.668 |

| Be consistent in making decisions | 0.550 | 0.535 | 0.764 |

| Focus on the task-at-hand | 0.527 | 0.512 | 0.609 |

| Keep up-to-date on management literature | 0.505 | 0.522 | 0.475 |

| Select work wisely to avoid overload | 0.480 | 0.491 | 0.547 |

| Be strict in judging the competence of employees | 0.453 | 0.427 | 0.723 |

References

- Yukl, G.A. Leadership in Organizations; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Selvarajah, C.; Duignan, P.; Nuttman, C.; Lane, T.; Suppiah, C. In search of the ASEAN leader: Exploratory study of the dimensions that relate to excellence in leadership. Manag. Int. Rev. 1995, 35, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Macarie, F.C. Managerial leadership-A theoretical approach. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2007, 3, 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lueneburger, C. The change leadership sustainability demands. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2010, 51, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nery-Kjerfve, T.; McLean, G.N. The view from the crossroads: Brazilian culture and corporate leadership in the twenty-First century. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2014, 18, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tideman, S.G.; Arts, M.C.; Zandee, D.P. Sustainable leadership: Towards a workable definition. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2013, 49, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, D.V.R.; Sasidhar, K.; Nayak, M. Integrative Framework for Spirituality in Leadership. Indian Institute of Management Udaipur Research Paper Series No. 2012-2171274. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2532321 (accessed on 16 September 2019).

- Hahn, T. Tensions in corporate sustainability: Towards an integrative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 127, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabh, P.; Singhal, M. Buddhism and decision making at individual, group and organizational levels. J. Manag. Dev. 2014, 33, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, P.; Singh, H.; Singh, J.V.; Useem, M. Leadership lessons from India: How the Indian companies drive performance by investing in people. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D.; Sukunesan, S.; Venkatapathy, R. Rise of India Firms-Understanding leadership in Indian organisations. In The Rise of Asian Firms; Chan, T.S., Cui, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 91–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and Identity; Penguin Books: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli, P.; Singh, H.; Singh, J.; Useem, M. Indian business leadership: Broad mission and creative value. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siderits, M.; Thompson, E.; Zahavi, D. Self, No self? Perspectives from Analytical Phenomenological, and Indian Traditions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Phadnis, U.; Ganguly, R. Ethnicity and Nation Building in South. Asia; Sage Publications: New Delhi, India, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, S.; Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D.; Dorasamy, N. Exploring Excellence in Leaderships Amongst South African Managers. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2014, 17, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R.M.; Ozbek-Potthoff, G. Implicit leadership in an intercultural context: Theory extension and empirical investigation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 15, 1651–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, N.M.; van Dick, R. Implicit theories in organizational settings: A systematic review and research agenda of implicit leadership and followership theories. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 1154–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Wood, G. Sustainable leadership ethics: A continuous and iterative process. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2007, 28, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, R.J.; Hauenstein, N.M.A. Pattern and variable approaches in leadership emergence and effectiveness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melwani, S.; Mueller, J.S.; Overbeck, J.R. Looking down: The influence of contempt and compassion on emergent leadership categorization. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1171–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Epitropaki, O.; Martin, R. Implicit leadership theories in applied settings: Factor structure, generalizability, and stability over time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, T.; Shore, L.; Strauss, J.; Shore, T.; Tram, S.; Whiteley, P.; Ikeda-Muromachi, K. Leadership perceptions as a function of race–Occupation fit: The case of Asian Americans. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 902–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pescosolido, A.T. Emergent Leaders as Managers of Group Emotion. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayman, R.; Korabik, K. Leadership-Why Gender and Culture Matter. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2010, 65, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, A.T.; Ortiz, F.A.; Katigbak, M.S.; Avdeyeva, T.V.; Emerson, A.M.; Flores, J.J.V.; Reyes, J. Measuring Individual and Cultural Differences in Implicit Trait Theories. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korac-Kakabadse, N.; Kouzmin, A.; Kakabadse, A. Spirituality and leadership praxis. J. Manag. Psychol. 2002, 17, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriger, M.; Seng, Y. Leadership with inner meaning: A contingency theory of leadership based on the worldviews of five religions. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 771–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R. Strategic leadership of corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Ananthanarayanan, R. Organisational Development and Alignment: The Tensegrity Mandala Framework; Sage Publications: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D.; Davuth, D. The effect of cultural modelling on leadership profiling of the Cambodian manager. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2012, 18, 649–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D. Profiling the Chinese Manager: Exploring Dimensions that Relate to Leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2008, 29, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D. Archetypes of the Malaysian Manager: Exploring Ethnicity Dimensions that Relate to Leadership. J. Manag. Organ. 2006, 12, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D. One Nation, Three Cultures: Exploring Dimensions that Relate to Leadership in Malaysia. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2008, 29, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D.; Jeyakumar, R.; Donovan, J. Flowers in a Greenhouse: Profiling Excellence in Leadership in Singapore. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 784–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D.; Donovan, J. Cultural Context and its influence on managerial leadership in Thailand. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2013, 19, 356–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D. Human capacity development in Indonesia: Leadership and managerial ideology in Javanese organizations. Asia-Pac. Bus. Rev. 2017, 23, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census. Census of Population and Housing of Sri Lanka, 2012. Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka. 2012. Available online: http://www.statistics.gov.lk/PopHouSat/CPH2011/Pages/Activities/Reports/CPH_2012_5Per_Rpt.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2015).

- Biziouras, N. The Political Economy of Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka Economic Liberalization, Mobilizational Resources, and Ethnic Collective Action; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bastians, D. US Hails Sri Lanka. DailyFT, Wednesday, 26 August 2015. Available online: http://www.ft.lk/article/462565/US-hails-Sri-Lanka (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Lee, H.; Reade, C. Ethnic homophily perceptions as an emergent IMRM challenge: Evidence from Sri Lanka during the ethnic conflict. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 1645–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shastri, A. Ending ethnic civil war: The peace process in Sri Lanka. Commonw. Comp. Politics 2009, 47, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratwatte, C. China, a Reality Check: Learning Lessons the Hard Way. DailyFT, 2 February 2015. Available online: http://www.ft.lk/2015/02/24/china-a-reality-check/ (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Nanayakkara, G. Culture and Management in Sri Lanka; Postgraduate Institute of Management, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka. Paper Prepared for United States Aid Mission. Available online: df.usaid.gov/pdfdocs/PNABB863.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Das, G. The Difficulty of Being Good: On the Subtle Art of Dharma; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrakumara, A.; Sparrow, P. Work orientation as an element of national culture and its impact on HRM policy-practice design choices: Lessons from Sri Lanka. Int. J. Manpow. 2004, 25, 564–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, A.T. Sri Lanka in global economy: Challenges for organizational leaders. Sri Lankan J. Manag. 2000, 2, 131–163. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, M.; Venkataraman, N. The place of self-Actualisation in workplace spirituality: Evidence from Sri Lanka. Culture Relig. Interdiscip. J. 2008, 9, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crews, J. Leadership values: Perspectives of senior executives in Sri Lanka. South Asian J. Manag. 2016, 23, 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram, T.; Casimir, G. The relationship between leadership and follower in-Role performance and satisfaction with the leader-The mediating effects of empowerment and trust in the leader. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2005, 28, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, H.H.; Schoorman, F.D.; Tan, H.H. A model of relational leadership: The integration of trust and leader-Member exchange. Leadersh. Q. 2000, 11, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormina, R.; Selvarajah, C. Perceptions of Leadership Excellence in ASEAN Nations. Leadership 2004, 1, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casimir, G.; Waldman, D.A.; Bartram, T.; Yang, S. Trust and the Relationship Between Leadership and Follower Performance: Opening the Black Box in Australia and China. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2006, 12, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, C.; Meyer, D.; Roostika, R.; Sukunesan, S. Exploring Managerial Leadership: Engaging Asta Brata, The Eight Principles of Indonesian Statesmanship. Asia-Pac. Dev. J. 2017, 23, 373–395. [Google Scholar]

- Irawanto, D.W. An analysis of national culture and leadership practices in Indonesia. J. Divers. Manag. 2011, 4, 41–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. Confucian global leadership in Chinese tradition: Classical and contemporary. J. Manag. Dev. 2011, 30, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewege, C.R.; Teicher, J.; Van Gramberg, B.; Alam, Q. Postmortem of post liberalization SOE governance in Sri Lanka: Duality of rational-Legal and feudal-Patrimonial. In Proceedings of the IRPSM Conference, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 26–28 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Willard, B. The Sustainability Champion’s Guidebook How to Transform Your Company; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakody, J.A.S.K. Charismatic leadership in Sri Lankan business organizations. J. Manag. Dev. 2008, 27, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.Y. China’s strategic engagement with Sri Lanka: Implications for India. Contemp. Chin. Political Econ. Strateg. Relat. 2017, 3, 1109–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Diven, P. Superpowers and small states: U.S., China, and India vie for influence in Sri Lanka. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the European Consortium on Political Research, Prague, September 7–10. Available online: https://ecpr.eu/Events/PaperDetails.aspx?PaperID=28830&EventID=95 (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Perry, P. Exploring the Influence of National Cultural Context on CSR Implementation. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 16, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, F.S. Toward a cross-Cultural understanding of work-Related beliefs. Hum. Relat. 1999, 52, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight-John, M.; Athukorala, P.P.A.W. Assessing privatization in Sri Lanka: Distribution and governance. In Reality Check: The Distributional Impact of Privatization in Developing Countries; Nellie, J., Ed.; Centre for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 389–429. [Google Scholar]