Abstract

Natural resource-based innovations (NRBIs), especially through the valorization of waste and side streams, have recently become a significant element of the bioeconomy agenda in several countries across the world. Accordingly, a variety of institutions, including universities, have been expected to contribute to such innovations. While there have been serious efforts within universities to play a key role in NRBIs, questions of the extent of institutional continuity of these efforts over time and how this can be achieved remain unanswered in the literature. This paper, therefore, seeks to identify the determinants of a highly institutionalized structure that is supportive of NRBIs in universities. By mobilizing a literature in which the level of structuration is conceptualized as the degree of institutionalization and by using a single case study of a Portuguese public university, it was found that several internal and external factors have contributed to the institutionalization process, which has led to the emergence of a sedimented structure. Despite a high degree of institutionalization, several challenges that have either impeded the harnessing of the full potential of NRBIs or that have posed a threat to the university’s highly institutionalized structure were also found. The paper concludes that the institutionalization of NRBIs within universities not only requires orchestrated organizational efforts but also more consideration of the social, economic, and political dynamics that have recently engulfed universities.

1. Introduction

Resource scarcity due to climate change and population increase has become a major problem in the world over the past few decades [1]. It has become rather difficult to access natural resources, and this, in turn, has rendered their more sustainable and effective use necessary. Bioeconomy has thus experienced a heightened emphasis, and many countries have started to search for innovative ways to valorize already existing natural resources and generate new products. Natural resource-based innovations (NRBIs) have likewise become a highly significant part of the European Commission’s innovation agenda [2].

Similar to innovation in other fields, innovation in the bioeconomy sector requires knowledge. Universities have therefore been expected to mobilize their knowledge capacity to spur innovation in the bioeconomy sector [3]. In response to such demands, serious efforts toward propagating bioeconomy activities have recently been observed in European higher education institutions. For instance, six universities have joined forces to intensify their cooperation within the field under a new initiative, entitled the European Bioeconomy University (EBU) (The EBU is an initiative in which six leading European universities (Hohenheim (Germany), Bologna (Italy), Eastern Finland (Finland), AgroParisTech (France), Boku Vienna (Austria), and Wageningen (the Netherlands)) that are strong in the area of bioeconomy are expected to intensify collaboration on research, teaching, and the valorization of biobased resources). Several other universities have also designed master programs in bioeconomy and have encouraged research, commercialization, and innovation in the sector [4]. While such initiatives are promising, questions of the extent of institutional continuity in these efforts over time and how this can be achieved within universities remain unanswered in the literature.

The bioeconomy literature regards universities as significant actors that can generate NRBIs and make important contributions [5,6,7,8,9], without a specific focus on how such activities function within university settings and how they get institutionalized. The higher education literature, on the other hand, situates NRBIs within the broader sustainable development framework [10,11,12,13,14,15], leaving out sufficient elaboration on their particularities. This paper thus aims to contribute to the debates regarding the involvement of universities in bioeconomy and bridge these currently disconnected fields. The following research question is asked: How do natural resource-based innovations get institutionalized within universities, and what are the factors contributing to their high degree of institutionalization? The literature around institutional theory that conceptualizes the level of structuration as the degree of institutionalization is used in the next section in order to answer this question. Delving deep into the exploratory nature of the research, the paper then focuses on a case study of a public university in Portugal, the University of Aveiro (UA), which is very active in engaging with bioeconomy. In the following sections, the paper then sheds light on the specificities of some NRBIs and the institutionalization process. The analysis demonstrates that it takes relatively a long time and an accumulation of targeted actions to build a sedimented structure supportive of NRBIs within universities. Moreover, there are several internal and external factors that have contributed to this process by providing legitimacy, encouraging potential adaptors, and mobilizing resources, all of which is described in Section 4. Despite the high degree of institutionalization, it is argued that there are two types of challenges that individual actors who lead such innovations face: (a) regulatory and practice-level challenges that make harnessing the full potential of NRBIs somewhat difficult and (b) systemic challenges that seem to be more serious and pose a risk of deinstitutionalization, albeit not in the very immediate future. Finally, the paper concludes that the institutionalization of such innovations within universities requires not only internal orchestrated organizational efforts, but also more consideration of the social, economic, and political dynamics that have recently engulfed universities.

2. Theoretical Framework

Universities are traditionally characterized as loosely coupled organizations that involve diverse academic units and groups [16,17]. For a new practice to be institutionalized, there needs to be an established organizational legitimacy, an appropriate value system [18,19], resource mobilization [20], and cultural–cognitive beliefs [21,22], and these should be supported by taken for granted assumptions [23]. The degree of institutionalization of NRBIs in universities then depends on the extent to which such activities are backed by these organizational aspects and the extent to which they are structured. With its holistic approach to organizational fields and the mediation between structure and agency [24,25], institutional theory provides a theoretical lens and terminology with which to analyze the institutionalization of NRBIs in universities.

Zucker (1977, p. 726) defines institutionalization as “a variable with different degrees of institutionalization altering the cultural persistence, which can be expected”. The institutionalization of new practices is not always manifested with equal intensity: institutionalization has degrees, and thus different phases. Barley and Tolbert (1997) argue that the difference stems from two sources: (a) the age of an institution and the time span of a given new practice and (b) the extent to which the new practice is accepted by different groups. Institutions (and structures) that have a long history and that have gained legitimacy, as well as extensive acceptance, by other actors in the field are more stable and harder to deinstitutionalize [26]. Institutional theorists have cross-fertilized arguments on institutionalization [22,26,27], drawing on insights from structuration theory, which focuses on the creation and continuity of social systems, such as structures [28,29]. One outcome of this synthesis is that “institutionalization is a process of structuration, and the terms can be used synonymously” [30] (p. 775).

Tolbert and Zucker (1999) identify three stages of institutionalization: habitualization, objectification, and sedimentation. Each phase represents different degrees of institutionalization. The first stage, habitualization, is the stage in which a new practice is introduced into the field by a relatively small number of members and achieves a degree of habitualized behavior. In this phase, the new practice is an independent activity and not well coordinated. There is no deeply shared value system surrounding it and no established agreement as to its continuation. Adoption of the new practice by other actors in the field is minimal. Such structures are temporary and not very stable, and they usually fade away over time [31].

The second stage of institutionalization is objectification. This stage includes some sort of consensus around the new practice and a growing adoption of it by actors in the field [31]. On the basis of this consensus, it can be expected that the actors who adopt the new practice have a vested interest in it ultimately becoming more heterogeneous. Such structures are usually more permanent, and they can be more stable, provided that there are external and internal conditions legitimating them, the discourse around them is high, and there is a significant level of resource mobilization as well as intergroup alliances [31].

Sedimentation is the last phase of institutionalization. It is defined as follows:

“…a process that fundamentally rests on the historical continuity of a structure and, especially, on its survival across generations of organizational members. Sedimentation is characterized both by the virtually complete spread of structures across the group of actors theorized as appropriate adopters and by the perpetuation of structures over a lengthy period of time”.[31] (p. 184)

In this phase, there is an extensive consensus around the new practice, its benefits, and its functionality. There are different groups who have some sort of interest in keeping the new practice, as well as in mobilizing their resources and triggering organizational dynamics to maintain it. Resistance from opposing groups is rather minimal or nonexistent, and it is frequently taken for granted. Such structures are quite stable, have a great influence on actors, and are normally hard to deinstitutionalize [31].

This perspective posits that the strength of structures depends on whether collective rationality and interests move from values and intentions to concrete exercises, such as organizations, laws, technologies, and funding allocations [32]. Depending on the specificities of such exercises, some organizational fields entail sedimented structures (highly institutionalized), while others involve habitualized or objectified structures that are still in the process of evolving {30]. Conceptualizing levels of structuration as degrees of institutionalization thus allows for exploring the emergence of a sedimented structure supportive of NRBIs in a university, which I will do in the following sections.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper seeks to identify the factors that contribute to the institutionalization of NRBIs in universities and to explore the challenges individual actors who engage in such activities face. The purpose and exploratory nature of this research required a deep approach and the selection of a university where such innovations have achieved a high degree of institutionalization over time. Therefore, it was decided to proceed with a single case study, as this enabled me to unearth the effect of a wide range of external and internal dynamics on an organization [33]. The university selected was the University of Aveiro (UA), a young university located in Portugal and characterized as entrepreneurial and innovative, which is reflected in its membership to meta-organizations such as the European Consortium of Innovative Universities (ECIU).

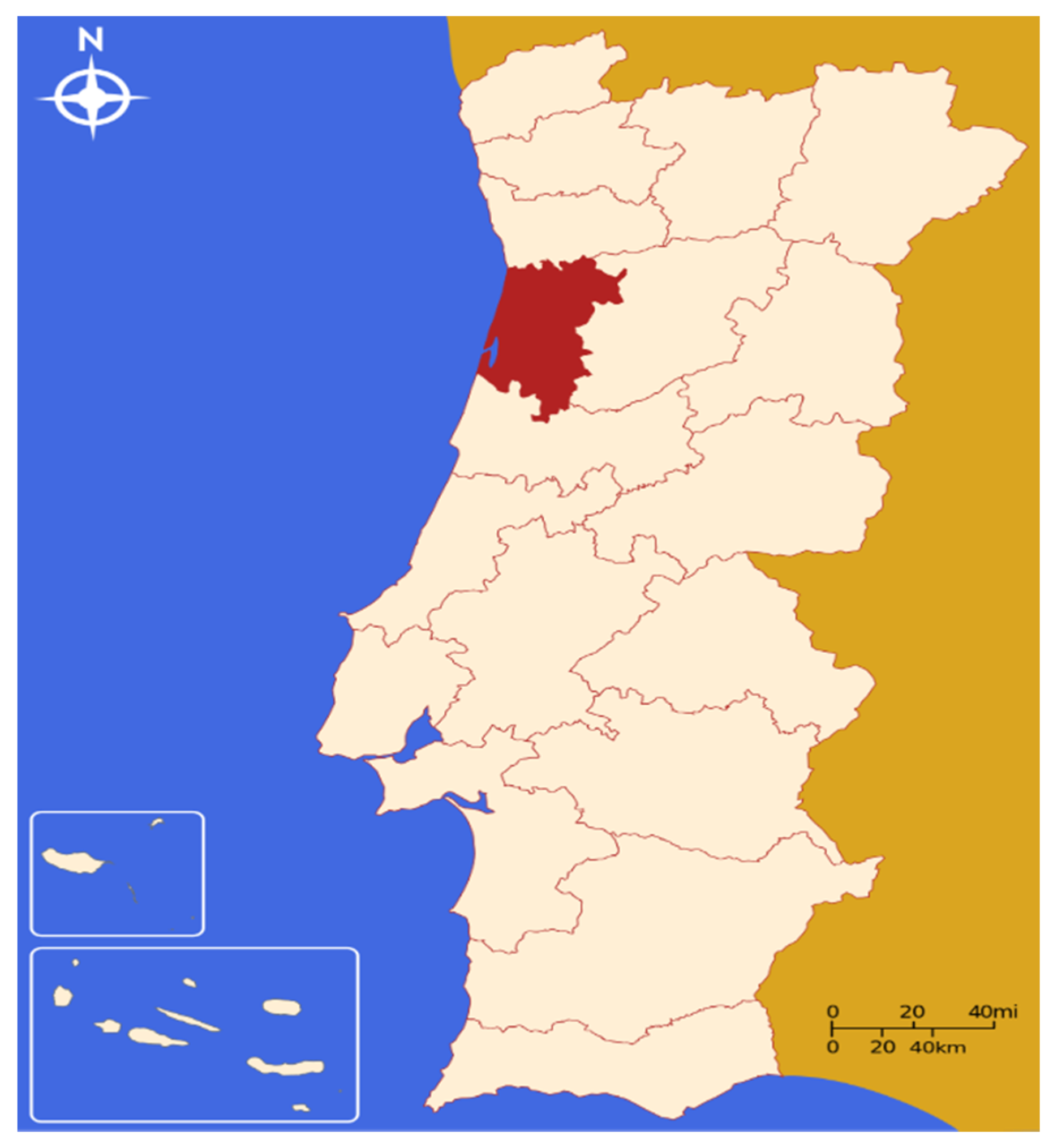

UA was established in 1973 with the mission of reviving regional socioeconomic prospects. As such, the university has extensively engaged with the surrounding region in many areas. The university does not have faculties, but rather 16 departments. Some of these departments are affiliated with commonly shared (by these departments) research centers, where most of the NRBIs seem to take place. The university is located in the Aveiro Region, in the center of the country (Centro Region, a statistical NUTSII subdivision). The region is abundant in natural resources because of the forests and coast (the Atlantic Ocean) where it is situated. This abundance is also reflected in its industrial structure: the fishing, cork, and pulp and paper industries are strong within the region. The location of the Aveiro Region can be seen in the Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Aveiro in relation to Portugal. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In order to access information on NRBI-related activities in UA, the projects listed on the website of each department and research center were mapped out. To acquire information on different aspects of NRBIs, such as the institutionalization process, historical continuity, and challenges, semi-structured interviewing was employed as a research method. Since the main goal in accessing information on NRBIs within UA was to find informants that had either academic and/or administrative experience in bioeconomy projects, criterion sampling was administered. Following that, a total of 33 individual academics involved in NRBI-related projects were identified. All 33 academics, as well as a member of the rectory team, an expert in a technology transfer office, and a manager of a company collaborating with UA intensively, were contacted to acquire an enlarged institutional perspective. Overall, 24 semi-structured interviews (21 with academics) ranging from 37 min to 85 min were conducted. A secondary source of information came through analyzing relevant reports, such as UA strategic plans and action plans, national/regional innovation and development strategy documents (namely Portugal 2020 and Centro 2020), as well as smart specialization strategies at both the national and regional levels. The choice of methods had a limitation though: the websites of the departments and research centers were mapped out to locate the NRBI-related projects in the university, but there might have been some projects that were not listed on these websites. Nonetheless, conducting interviews with 21 out of the 33 available academic staff and 3 members from the rectory team, technology transfer office, and a company enabled me to acquire sufficient data, with which the institutionalization process was analyzed. The distribution of interviewees across units is provided in the Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Number of interviewees for each unit.

Each interview focused on a set of questions and discussions on the following topics: (a) the time (exact or approximate) academics began engaging with such activities; (b) the kind of products that are generated through such innovations; (c) the challenges interviewees have faced so far; (d) the impact of the external environment and dynamics on these activities; (e) collaboration partners and networks (within UA and across organizations); (f) the factors that facilitate these activities; and (g) the personal and institutional gains from engaging in such activities. The answers were transcribed and inductively coded later [34], and the content was thematically analyzed [35]. The analysis indicated that external factors considerably legitimize these activities and provide significant financial resources, while internal organizational-level efforts facilitate them through newly created organizations, thereby reinforcing the institutionalization process. However, there are significant dynamics in both dimensions (internal and external) that, at the same time, impact these innovations negatively, some of which pose a further threat to this highly institutionalized structure. A representative sample of such innovations and their specificities is now provided, and then the emergence of a sedimented structure supportive of NRBIs and signs of a high degree of institutionalization are addressed.

Academics in UA have engaged in a variety of innovations based on natural resources, ranging from eucalyptus bark and apple peels to microalgae and seaweed. A detailed description of some of the innovation activities and their outcomes is provided in the Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Specificities of natural resource-based innovations in the University of Aveiro (UA).

Some of the products emerging through these innovations, such as food supplements, seaweed powder, and feedstock, are already on the market, thanks to collaboration with some local and international firms, while others, such as microscopic films and biopolymers for the pharmaceutical industry, are either in the process of finalization or in beta tests.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Path to a Sedimented Structure and Signs of a High Degree of Institutionalization

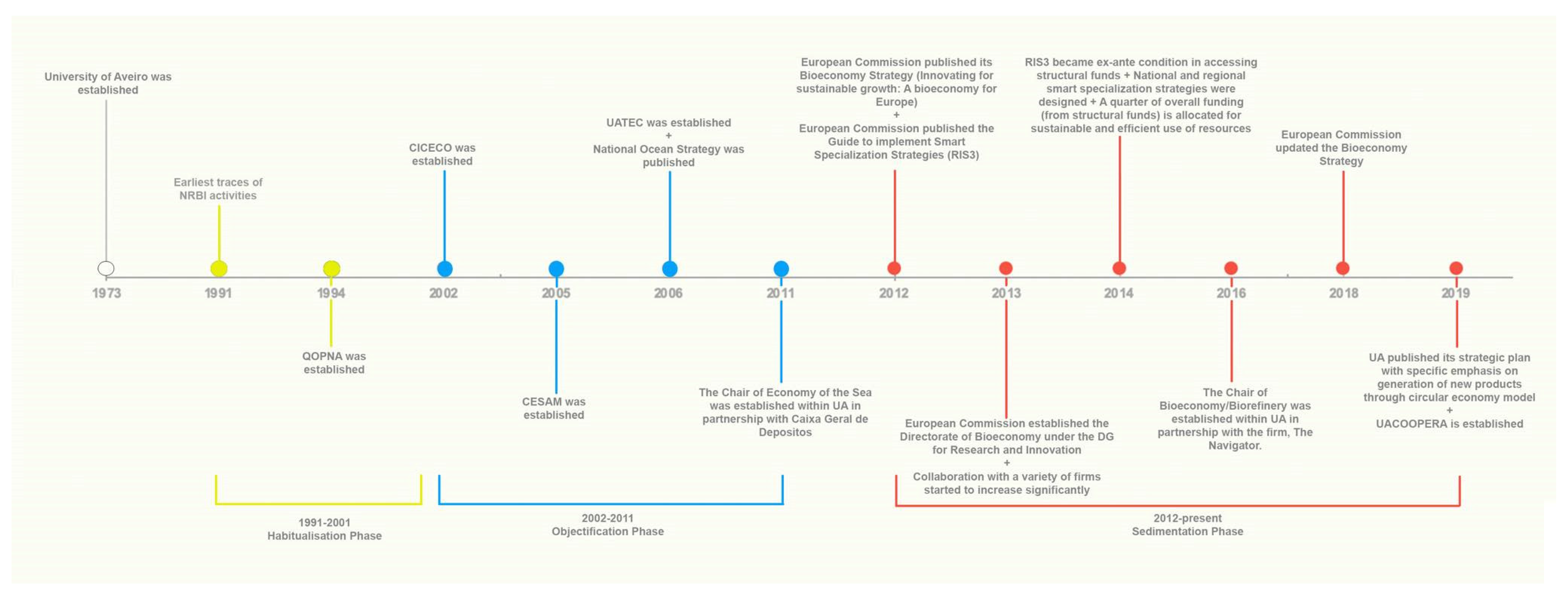

While it is rather difficult to pinpoint the exact time period when an NRBI-based structure have passed through the habitualization, objectification, and sedimentation phases, it was still possible to identify approximate timelines, based on the documentary data and interviews. The history of NRBIs was traced back to as early as 1991, thereby indicating that the institutionalization process has at least 29 years of history. As such, my attempts to identify these three phases began with this particular year.

The first phase, habitualization, took place between 1991 and 2001. During these years, engaging with NRBIs was an activity of some academic staff, who were mostly from the chemistry, biology, and environment and planning departments and the research center QOPNA (Organic Chemistry, Natural Products, and Food Stuffs, established in 1994). The involvement of other disciplines was visible, yet rather limited. Research and innovation based on natural resources was economically and technically a costly endeavor. In addition, support from the external environment in providing legitimacy and resource mobilization was minimal to none.

The second phase, objectification, occurred in the years between 2002 and 2011. During this phase, the structure became more permanent and widespread in the sense that two more research centers, CICECO (the Aveiro Institute of Materials) and CESAM (the Center for Environmental and Marine Studies), were established in 2002 and 2005, respectively, and the departments involved in such activities (i.e., the Department of Economics, Management, Industrial Engineering, and Tourism (DEGEIT), the Department of Geosciences, and the Department of Materials and Ceramic Engineering) became more heterogeneous. In 2006, UATEC (the Technology Transfer Office) was established, which provided needed support for biobased start-ups and spin-offs. The first signs of external legitimacy also appeared, with the publication of the National Ocean Strategy in 2006 and an emphasis on the blue economy [36]. In addition, the Chair of the Economy of the Sea was founded in 2011, together with the state bank Caixa Geral de Depositos. Innovation and research based on natural resources was still a costly enterprise, yet economically and technologically, it had become more viable, compared to the previous phase.

The last phase, during which the structure became sedimented, reaching a high degree of institutionalization, took place from 2012 onwards: UA has thus sustained historical continuity of the structure for 29 years. New units have been established in the university to support these activities, and external legitimacy and resource mobilization have been further strengthened at the regional, national, and European level (see Section 4.2). The number of bioeconomy projects has multiplied. These activities have started to produce outcomes that are in line with institutional goals, such as attracting external funding and increasing scientific publications, thereby helping UA’s position in the rankings. Opposition to such innovations seems to be little to none.

Further signs of a high degree of institutionalization include research and innovation based on natural resources being taken for granted. This was articulated by a member of the academic staff: “Our students have already started to suggest this (research on the valorization of natural resources) as their thesis topic. We do not push them towards this specifically.” (Chemistry, 5). Another member of the academic staff reflected on the extent of research and innovation based on natural resources within the university:

“I am not even from these disciplines (chemistry and biology), and whenever I go to a conference or a meeting, especially in Europe—when I tell them I work in the University of Aveiro—they know it because of two things: entrepreneurship and bioeconomy. Even the people in my own discipline. I mean I understand entrepreneurship, but I was really surprised that many people know bioeconomy.”(DEGEIT, 2)

Faculty members, particularly those in chemistry and biology departments, quite often receive requests from foreign PhDs and postdocs, who would like to make either short- or long-term research visits to work on their research projects relating to NRBIs. Additionally, the departments that are involved in these projects have become even more heterogeneous, with atypical collaborators, such as the Department of Biology and the Department of Electronics, Telecommunication, and Informatics.

4.2. Factors Contributing to the Institutionalization Process

There are several factors that have legitimized and facilitated NRBIs in UA, thereby substantially contributing to the institutionalization process. In this section, these factors are divided into two groups, external and internal, and then their characteristics are elaborated on.

4.2.1. External Factors

The external environment of UA is composed of three main layers: a regional (Centro Region), national (Portuguese government), and supranational (European Commission/European Union) layer. In the outer circle lies supranational entities, and the analysis here starts with this particular layer. There has been a heightened emphasis on bioeconomy and innovation at the European level, particularly since 2010. The European Commission published a bioeconomy strategy entitled “Innovating for Sustainable Growth: A Bioeconomy for Europe” in 2012 [37], and it has established a bioeconomy subdivision under the Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. The strategy was later substantially updated, calling for greater contributions from universities [2]. Both the Commission and the European Union have also supported bioeconomy-related initiatives, such as the EU Bioeconomy Network (https://eubionet.eu) and the European Bioeconomy Alliance (https://bioeconomyalliance.eu/). The discourse around bioeconomy has been strong and visible, with many talks and interviews from European Commission-level individuals, such as the Commissioner (2014–2019) for Research, Science, and Innovation, Carlos Moedas (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GqV_3kvo-Rc), and the Director for Bioeconomy (DG RTD), John Bell (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sASZyaEOnHk). Furthermore, the European Commission published a guide in 2012 on how to develop, implement, and monitor smart specialization strategies (RIS3), a policy concept that embodies a place-based approach to innovation and places great emphasis on the local strengths and assets of a given region, including its natural resources. The Commission decided to make it an ex ante condition for regions that aim to benefit from European Structural and Investments Funds. That is, these regions now need to develop their own smart specialization strategies based on their regional strengths to be able to utilize structural funds for research and innovation projects within their geographical vicinities.

The second layer is composed of the national environment. The Portuguese government prepared its national smart specialization strategy (Estrategia de Investigaçao e Inovaçao para Uma Especializaçao Inteligente) in 2014. The strategy has four pillars, one of which is “To Valorize Endogenous Resources” (translated) [38] (p. 6), an area that serves bioeconomy endeavors well. The priorities section of the strategy document entails the fourth thematic axis of “Natural Resources and Environment” (translated), with clearly emphasized subthemes: agri-food, forests, the sea economy, and water and the environment [38] (p. 6). A related budgetary program document, Portugal 2020, further reinforces the areas to which € 25 billion (up to 2020) is allocated. One of the specified areas is the “Sustainable and Efficient Use of Resources” (translated), for which a quarter of the available funding is allocated [39]. These documents set out very clearly that innovation in bioeconomy activities is a national priority, and it is highly encouraged. Regions are expected to develop their own smart specialization strategies that are in line with the national one, which puts the focus on the closest circle of UA, the regional layer.

The Centro Region (the third layer) also developed its smart specialization strategy in 2014. One of the four domains specifically addresses the “valorization and efficient use of endogenous natural resources” (translated) [40] (p. 9). Under this domain, there are action points targeting specific innovation areas, such as the sea, forests, materials, agriculture, biotechnology, and rural innovation [40] (p.10), which are supportive of NRBIs. The strategy is significant and binding in the sense that research and innovation projects proposed by universities, firms, or other entities are required to link to these regional domains in order to be able to benefit from the allocated funding. At the regional level, it is not only the Centro Region’s smart specialization strategy that has provided fertile ground for bioeconomy activities. The region also possesses a considerable knowledge base and a variety of firms that are interested in innovation within the bioeconomy sector. In addition to UA, there are also two other universities in the region, the University of Coimbra and the University of Beira Interior, with which collaboration on NRBIs takes place. Furthermore, there are several companies (such as Sonae, a multinational company that possesses one of the two biggest retail firms in Portugal (Continente), and Algaplus, which is a small firm specializing in seaweed and microalgae production) that are interested in NRBIs and collaborate with UA extensively.

4.2.2. Internal Factors

A similar regulatory mobilization can be found within UA as well. To illustrate this, sustainability is one of the 10 values and principles in the strategic plan, and there are two dimensions, namely “actively contribute to regional development” (translated) and “link research and teaching to sustainable development goals (SDGs)” (translated), both of which emphasize “multistakeholder partnerships to foster the generation of new products and accord research activities, with a view toward contributing to the sustainable development of the region” (translated) [41] (pp. 44–45). The action plan further reinforces the generation of new products, including those generated through NRBIs, as the following statement indicates:

“To achieve this goal (working toward sustainable development goals), it is necessary to support entrepreneurial initiatives within the circular economy with the potential to generate new products, new processes, and new forms of organizations. This should also strengthen links with the social fabric of the region, multiple institutions, and the third sector”.(translated) [42] (p. 28)

There have also been other strong efforts to structure these activities across the organizational field. In 2013 and 2014, UA established eight technological platforms, of which three specifically were intended to spur innovation in the bioeconomy sector: the Agri-Food Technological Platform, the Technological Platform of the Sea, and the Technological Platform of the Woodlands. Both academic and administrative personnel work on these platforms, and they provide support in many areas, including bureaucratic challenges when applying to national and international funding agencies for bioeconomy-related projects and channeling external entities (with the aim of getting them to cooperate with UA in the bioeconomy sector) toward the right people with specific expertise on the subject matter:

“In the technological platforms, there are many postdocs from several areas that support us in all administrative and bureaucratic aspects that are needed for these types of projects (bioeconomy). They are very, very important for us. I would always keep the platforms.”(Chemistry, 1)

“Our main aim there (in the technology platform of the sea) is to be the first port of entry when someone comes to the university and says ‘I have a problem with this. Can you help me?’ Because what we have realized in the past is that you come to the university, knock on my door, and say ‘Hey, I have a problem with cows’ and I say ‘Look, I work with fish, sorry’. End of interaction. Now, we overcome this through technological platforms.”(Biology, 2)

At the time of this paper being written, UA was undergoing a change in its organizational structure related to its links with the region. A new organization, UACOOPERA (Unidade Transversal Para a Cooperaçao com a Sociedade), was created to support several university units in their cooperation with external partners and minimize fragmentation. There seems to be a serious intention to ensure that UA continues to emphasize the role of technological platforms in supporting NRBIs within the new restructuring: the university has organized its technical competencies regarding regional engagement into nine areas, three of which are highly relevant for bioeconomy activities (namely Food and Agriculture, Forestry, and Marine), while two others (Industrial Products and Processes and Territories, Development, and Habitat) can provide partial support.

The technology transfer office (UATEC) has also stepped in to assist on several aspects of innovations within the bioeconomy sector: patenting, licensing, financial advice, encouraging the establishment of start-ups, and mediation between academic staff and companies. Moreover, UA has established two related guest chairs in partnership with well-known entities, the Economy of the Sea–Caixa Geral de Depositos (a state bank) and Biorefinery/Bioeconomy–the Navigator (a pulp and paper company).

Multidisciplinary research centers have been at the heart of NRBIs. In particular, CICECO, CESAM, and QOPNA are the three biggest centers in which research and innovation activities associated with natural resources are concentrated. They are supported by GOVCOPP (Governance, Competitiveness, and Public Policies), a research center that incorporates perspectives from different disciplines, ranging from economics and management to urban planning and public policy. The multidisciplinary aspect of these research centers has facilitated the scaling up of natural resource-based research and innovations by providing an organizational platform in which cross-fertilization between different disciplines can increasingly be achieved. A summary of all the external and internal factors contributing to the institutionalization process and their chronological reflection can be found in the Table 3 and Figure 2 below, respectively.

Table 3.

Factors contributing to the institutionalization process. NRBI: natural resource-based innovation.

Figure 2.

A timeline of external and internal factors supporting NRBIs in UA and the degree of institutionalization within the three phases.

Many of these innovations have so far yielded quite novel findings, as well as new products, which ideally serves the second mission of the university—research—well. More specifically, the novelty of the findings emerging from the projects provides researchers with the opportunity to disseminate them through scientific publications. This benefits researchers in terms of their career progression, since high-quality publications still remain one of the most important requirements for academic promotion, if not the most important. These projects have also attracted a significant level of funding from a variety of external sources. Overall, publications and the level of funding attracted then contribute to achieving an institutional goal that has experienced a heightened emphasis, particularly in the last two decades, i.e., a better performance in global university rankings.

4.3. Challenges and Risks to the Institutionalized Structure

So far in this paper, the determinants of the institutionalization of NRBIs in UA have been covered. Despite the emergence of a sedimented structure supportive of NRBIs, there have also been challenges, some of which seem to be putting the institutionalized structure at risk. In this section, the regulatory and practice-level challenges that make harnessing the full potential of such activities within UA difficult are addressed first. Following this, systemic challenges that go beyond impeding these activities and pose a risk to the institutionalized structure in the long term are then elaborated on.

The mobilization of financial resources has, so far, significantly contributed to the institutionalization of NRBIs. Nevertheless, instability regarding the level of funding and success rate of the funding granted by external organizations, such as the Foundation for Science and Technology in Portugal (FCT), as well as continuous changes in the rules and regulations regarding project applications, challenge these activities, as was expressed by two academic staff members:

“Instability is the problem: instability in the sense that the level of funding, the mechanisms for funding, the platforms on which we submit the projects, the reporting rules, etc., are changing quite often. The amount of funding available either for projects or directly applied to human resources, etc., is changing in a dramatic and somewhat unexpected way.”(Geosciences, 1)

“Typically, the level of funding [success rate] when you submit a project is in the range of 10% or 13%, like in most of Europe. This is absolutely frustrating, because you spend a lot of time preparing the project, and as a consequence, there were many people who said, ‘I will not even apply. It is a waste of time.’ In that year, FCT funded around 60% of the projects. It is good in the sense that the system needs a lot of funding, because we have gone through this crisis. However, then, many people got frustrated again about this. In this sense, the system needs to be more predictable.”(Material and Ceramic Engineering, 1)

The instability in the success rate seems to impact NRBIs negatively in the sense that faculty members have difficulty predicting which year will be the best to apply for funding, thereby limiting the number of bioeconomy projects that could find a home in the list of approved projects all over Portugal. However, it is not only the level of instability and continuous changes in rules that create funding-related challenges: regulations on how to spend externally acquired funding also create hindrances, as one academic staff member articulated:

“We have a large amount of rules that cannot be directly applied to managing these [bioeconomy] projects. That is a very big constraint. For instance, when you have a contract with the industry and you are receiving the money, for example, in October, you have to spend the money in the same civil year. So, you receive the money in October and cannot spend it all until the end of December. You are losing all the money. I lost lots of money, and I was not able to complete projects because of that.”(Chemistry, 4)

The regulations related to financial spending stem from the austerity period, during which the Portuguese government decided to increase its control over organizational spending and money inflow/outflow across the institutions of the country.

Most NRBIs also require cooperation with external stakeholders, such as firms and other public/private organizations. However, the expectations of universities and firms in terms of these innovations can change considerably, which can pose a challenge to intensive cooperation, which is needed for such innovations. An academic staff member that extensively collaborates with firms on such innovations noted the following:

“We need to understand that with the outcomes of applied research like this [bioeconomy], we need to be aware of the needs of firms. That is completely different when we do fundamental research. We are very lucky in this case [referring to collaboration with a specific company], because X [the manager of the company] has a PhD degree and even a postdoc. It helps a lot that X understands us, but unfortunately, this has not been the case in collaboration with other firms.”(Biology, 3)

“I always tell them (academic staff at UA) that sometimes I wish there were ideas more focused on the commercial side of the product (rather than publications) coming from the university. I wish someone came and told me ‘Why don’t you use this product?’ For that, they are always waiting for the company to provide all of the information.”(Manager of a company)

While university–firm interactions pose challenges that have not yet been overcome, a new challenge has appeared on the horizon because of new external partners, namely public and private organizations such as cooperatives, associations, and municipalities. Many academic staff members noted the difficulty of having these partners on board with respect to working toward NRBIs. Some of them discussed the financial capacity of these organizations: “Sometimes you (as an institution) need to spend money before you receive money from the EU (Interreg Projects), which is fine for the university. They put the money forward, because they know in 6 months’ time, they will get the money, but for small businesses and these kinds of organizations (fishing-related associations), this is not easy.” (Environment and Planning, 2). The others addressed the novelty of these collaborations for both partners:

“I think the biggest difficulty is not even not knowing people from academia. I think academics kind of speak the same language and understand each other, even if they do not know each other. But this bridging with people in these organizations [the fishing industry and fishing-related associations and municipalities] is so, so difficult. Explaining to them what the project is about, getting their interest, convincing them that the project is viable and explaining the rules and procedures (of EU-funded projects) is very challenging.”(Environment and Planning, 1)

However, not all of the challenges stem from the external environment in which UA operates or external stakeholders with which UA collaborates. Some of them arise due to the internal organizational environment, as articulated by an academic staff member:

“What we need to understand is that when an enterprise decides to go to a university to say ‘we need you to develop this project with us’, they have thought about it many, many times already, and they have made all the calculations. So, when they do this, for them it is completely unacceptable that you take one month to decide whether you are in or out.”(Biology, 4)

In addition, academic promotions are still heavily dependent on publication outcomes, which can be observed as another challenge in engaging with NRBIs. Some of these activities lead to publications, which are still highly influential in academic promotion and generate external funding for the university, while some others do not. When they do not, the question emerges as to what the professional benefits are of engaging with such activities for individual academics. The only source of motivation is then purely altruistic, which may not be enough to structure these innovations across the field and cannot be taken for granted: “I have pleasure doing them [NRBIs]. I do not get anything from doing them. This is a very unfair thing, but that is the way. Our system unfortunately does not encourage them or recognize their value.” (Chemistry, 4). Moreover, “I am sad for my postdocs or assistant professors here, who will not be able to progress in their career while doing them and will likely give up or significantly decrease the number of projects.” (DEGEIT, 1). This seems to have an impact mostly on assistant professors that are on a probation period, during which scientific publications have a significant determining power on promotion, as well as postdocs.

All these external and internal challenges make harnessing the full potential of NRBIs in UA considerably difficult, yet they do not shake the institutionalized structure dramatically. Nonetheless, three systemic factors that pose a serious threat to this institutionalized structure and possess the potential to trigger a deinstitutionalization (in the long term) were identified. The first of these concerns external shocks, e.g., financial crises and subsequent austerity periods. The impact of the 2008 financial crisis started to be more visible in 2011 (and after). The outcome was an austerity policy, which had a severe impact on universities across the country. Higher education institutions experienced substantial budget cuts, particularly in 2012 and 2013, which had a detrimental impact on NRBIs in UA. When asked about continuity in such innovations, all participants referred to the period of 2012–2013, stating that the number of such projects was either zero or diminished by at least half, except for one academic staff member, who was able to sustain a number of projects because of intensive collaboration with European partners and by securing prestigious European-wide research grants. Even so, the academic stated that such an achievement was extraordinary, unexpected, and almost impossible to replicate. Budget cuts impacted bioeconomy activities negatively, such that there was significantly less funding available for such projects (particularly from the FCT) and significantly fewer PhD scholarships and postdoctoral fellowships (groups of qualified researchers that have played a key role in NRBIs). With such austerity and economic uncertainty still looming, worries as to what the next external shock(s) might take from such innovations remain.

The second factor that poses a threat to the institutionalized structure is the rise of rankings in the higher education sector and its rapid permeation of organizational fields in universities. In a relatively short period of time, rankings have gone from being a set of indicators for universities to a mechanism through which universities try to build a competitive advantage, status, and prestige. UA has not been exempt from this, and the importance of rankings has increased. To illustrate this, a recent document that provides information about the university (e.g., facilities, research capacity), which was published in 2018, starts with the position of UA in the global rankings on the first page [43]. Moving up in the rankings requires increases in the number of publications and citations and in the amount of research funding (and, to a small extent, industry income, e.g., see the Times Higher Education Rankings). Rankings have, until recently, contributed to the institutionalization of NRBIs in UA, as some of the projects have resulted in impactful publications and industry income. However, many of these projects have not led to publications or have not attracted a significant amount of external funding, thereby, ironically, turning rankings into one of the biggest threats to the institutionalized structure. In recently released rankings, UA was 4th (sharing the position with five other universities) nationally out of 13 universities in one ranking [44], and it was positioned in 5th place nationally out of 7 universities in another [45].With increasing discourse on rankings across the organizational field in the university, the possibility has emerged of UA aiming to better its position nationally and globally in the coming years by placing more emphasis on fundamental research and securing prestigious grants, for instance, from the European Research Council. This might result in taking attention away from bioeconomy projects, which usually entail applied research and do not necessarily lead to publications, risking the continuity of NRBIs (as articulated by many academics).

One last factor threatening the continuation of the sedimented structure supportive of NRBIs relates to the demographic characteristics of the individual academics that lead these innovations. There are many senior academics (including those who were identified as significantly contributing to these innovations but with whom securing an interview was not possible) that are in their mid- or late-60s. Those who were interviewed expressed their intention to reduce their engagement with NRBIs and/or retire soon or within the next decade. In the meantime, there are not enough positions advertised for newly graduated PhD students and postdoctoral fellows who have been supervised by these senior academic staff and who have developed research and professional expertise on NRBIs. The problem is exacerbated when these new PhD graduates or postdocs are not able to stay in Portugal, but rather have to look for academic jobs abroad, which makes collaboration on these projects more difficult, as many of them require close interaction with nonacademic partners. Furthermore, there is also no guarantee that newly hired assistant professors will engage in such activities for a long time, especially if they are on a probation period, during which time publications are a significant benchmark for promotion. While all of these dynamics already produce some hindrances to the continuity of NRBIs, it can be inferred from the findings that the intensity of these three challenges (austerity and economic uncertainty, rankings, and demographic characteristics) might further increase and pose serious risks to the sedimented structure within the next 10–15 years, unless the specificities of these dynamics change substantially. A summary of these types of challenges is provided in the Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Challenges to the institutionalization process.

5. Conclusions

This paper sought to explore how NRBIs become institutionalized in universities and the factors that contribute to and challenge the institutionalized structure. In the theoretical framework, the level of structuration was conceptualized the degree of institutionalization in order to be able to account for how a structure supportive of NRBIs (that is, reaching a high degree of institutionalization) becomes sedimented. This was conducted empirically in a public university that has a relatively long history of and active engagement with NRBIs.

Within this framework, the institutionalization process requires legitimacy, appropriate values, resource mobilization, and cultural–cognitive belief systems. Assumptions that are taken for granted and an increasing heterogeneity of adaptors of the new practices strengthen the institutionalization process to such a degree that it becomes sufficiently sedimented and can exert power over both existing and newly arrived actors in the field. The case of UA demonstrates that the characteristics of these organizational aspects play a key role in what kind of university activities become institutionalized, as well as how and when they achieve a high degree of institutionalization. Therefore, this study contends that this perspective (conceptualizing the level of structuration as the degree of institutionalization) might be generally helpful in analyzing how other university activities achieve a high level of structuration and how other organizations can institutionalize contributions to NRBIs, particularly at a time when public entities, such as municipalities, are also increasingly expected to play an important role in NRBIs within their localities [46].

Legitimacy and resource mobilization are manifested through multiple layers (European, national, and regional levels) and sources. Clarity in the discourse on bioeconomy and emphasis on the sustainable use of endogenous natural resources (which were found throughout various documents, such as the strategic plan of the university and national/regional smart specialization strategies) have significantly facilitated the establishment of the legitimacy process of NRBIs as a university activity. A similar explicit message was observed in resource mobilization, with almost a quarter of structural funds being allocated for these activities nationally, which has further been enriched by willing firms who can also deploy significant financial resources to NRBIs. These externally triggered dynamics have found institutional resonance within the university, and UA has responded by creating new units, structures, and organizations and by mobilizing human resources. These new units, structures, and organizations have considerably facilitated NRBIs, which, in turn, have aided in the emergence of a cultural–cognitive belief system and taken-for-granted assumptions. More specifically, an externally triggered and internally complemented legitimacy process and such a significant level of resource mobilization have resulted in the perception of actors that NRBIs are at the core of the organizational agenda. Newly arrived members in the field now take this assumption for granted, although there have been cases in which they either give up or reduce their level of engagement with NRBIs after a couple of years due to the strong emphasis on publications in academic promotions.

As the case study demonstrated, sedimented structures are not exempt from challenges. Some regulatory and practice-level challenges found here, such as different expectations from university–firm collaborations, a strong emphasis on publications in academic promotions, and negative impacts on various third-mission activities, concurs with the findings within the recent literature [18,47], thereby facilitating an extrapolation that they will likely continue to be seen in universities’ regional contributions and in industry collaborations, unless there is a substantial change in academic promotion. A slow internal decision-making process can be explained by the characterization of universities as loosely coupled organizations composed of different academic units and hierarchies [16], which needs more consideration and should be taken into account by organizations willing to collaborate with universities. Instability in the level of funding and financial regulations related to institutional spending are ramifications of the austerity measures that have surrounded Portuguese universities. Difficulty in cooperating with newly emerged partners, such as associations, nongovernmental organizations, and municipalities, highlights the increasing role of civil society in the innovation process in the form of a quadruple helix. This necessitates a more nuanced understanding of the organizational structure of these new innovation partners in order to overcome challenges in their collaboration with universities, including those focused on NRBIs.

Three dynamics that stem from external and internal forces that pose risks to the sedimented structure were also observed: financial crises, ongoing austerity, and economic uncertainty; university rankings; and the demographic characteristics of academics. The 2008 financial crisis and the following austerity measures definitely left a negative legacy on universities, impacting NRBI activities. While Portugal is recovering from the recession slowly, the austerity measures are still not over, and economic uncertainty has not yet disappeared. To illustrate this, the public debt looms at around approximately 120% of the GDP, making it the third highest in the Eurozone [48]. This limits the amount of foreseeable investment in universities and bioeconomy projects. The result of this is significantly fewer assistant professor positions, doctoral scholarships, and postdoctoral fellowships. In this sense, it seems paradoxical that, since the financial crisis, university resources have been significantly slashed as part of the austerity measures, while at the same time, expectations from universities to further mobilize their resources to contribute to the development of their regions and society have considerably grown in the national context. The seniority of academics that engage in such innovations further risks the institutional continuity of NRBIs. This risk might be exacerbated with the removal of smart specialization, a policy tool that has so far provided a fertile ground for NRBIs, as an ex ante condition for accessing structural funds from the European Commission’s next budgetary program in 2021–2027 [49], making the structure more susceptible to external shocks in the future.

One striking finding of the paper is how rankings have been transformed from a catalyst for NRBIs, considerably contributing to the institutionalization process through publications, into one of the biggest external forces threatening the sedimented structure. One possible reading might be that the importance of rankings has steadily grown since the early 2000s, and they have recently become more utilitarian than ever, as authorities, governments, and students base their decisions and investments on them [50]. In light of institutional theory, this suggests that the degree of intensity of an external factor seems to determine whether it contributes to the institutionalization of a structure or poses risks to it (or both) in different phases. Future research can further elaborate on when and how an external factor ceases to support a highly institutionalized structure and instead becomes a threat to its long-term existence, with the potential to trigger deinstitutionalization. Future research can also focus on the institutionalization (or the lack thereof) process of NRBIs in other organizations, such as local governments, municipalities, firms, and associations, delving deep into the similarities and differences between these organizations, including universities, to formulate tailored institutional strategies fostering NRBIs.

This research is an intensive single case study of a young and entrepreneurial university, for which regional engagement has been a very important mission since its establishment and which has a relatively long history in engaging with NRBIs. It has been operating in an environment in which bioeconomy has become a priority at multiple levels, thereby providing a conducive environment for NRBIs. This suggests a potential implication for applying these findings to other higher education institutions. Universities that position themselves globally (striving for excellence) rather than intensively engaging with their own region (although this is not necessarily a binary system) and/or universities that are located in environments in which resource mobilization for bioeconomy and the discourse on it is limited might find it quite challenging to institutionalize NRBIs.

This study clearly suggests a number of policy implications. Firstly, it is time for policymakers, authorities, and governments to reconsider their treatment of rankings as a benchmark for university quality and as a criterion according to which significant resources are distributed across higher education institutions. Under the current circumstances, universities are compelled to compete with each other, which has a negative impact on individual academics, as they start to focus on publications and securing external grants to contribute to moving their universities up on the ranking tables. Secondly, policymakers have an important role to play in legitimizing various university activities and rendering them valuable by constructing a discourse around them and mobilizing different kinds of resources (e.g., financial, human, and regulatory resources). As the findings demonstrate, it is recommended that the policy sphere be explicit in their expectations of universities. In this regard, while the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) constitute a timely and relevant point of departure for a variety of university third-mission activities, including NRBIs, expecting universities to contribute to the SDGs (a growing anticipation increasingly articulated by policymakers in recent years) [51] remains a rather broad policy demand. There is a need to delve deeper into the specificities of SDGs and for a more nuanced articulation of expectations from universities.

In sum, this study attempted to bridge two disconnected fields of research, namely bioeconomy and higher education studies, in light of the growing expectations of universities to mobilize their knowledge capacity and resources for NRBIs. This paper maintains that the institutionalization of such innovations in universities depends on well-coordinated internal organizational efforts, a significant time span for structuration across the field, and external factors that can provide legitimacy and considerable resource mobilization, which encourages potential adopters. Nevertheless, even sedimented structures can be susceptible to external and internal shocks, especially when the sedimentation phase is rather young, and this may eventually trigger deinstitutionalization. In this sense, it is important that sedimentation not be conceptualized as an end goal, but rather as a phase during which the structure can and should still be strengthened in order to allow it to survive across generations of actors.

Funding

The author acknowledges that the paper was supported by funding from the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions), grant agreement no. 722295.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bergstrom, J.C.; Randall, A. Resource Economics: An Economic Approach to Natural Resource and Environmental Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection between Economy, Society and the Environment. Updated Bioeconomy Strategy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, K. Knowledge, place, and power: Geographies of value in the bioeconomy. New Genet. Soc. 2012, 31, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetemäki, L.; Hanewinkel, M.; Muys, B.; Ollikainen, M.; Palahí, M.; Trasobares, A. Leading the Way to a European Circular Bioeconomy Strategy; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2017; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Arujanan, M.; Singaram, M. The biotechnology and bioeconomy landscape in Malaysia. New Biotechnol. 2018, 40, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberman, D.; Kim, E.; Kirschner, S.; Kaplan, S.; Reeves, J. Technology and the future bioeconomy. Agric. Econ. 2013, 44, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainez, M.; González, J.M.; Aguilar, A.; Vela, C. Spanish strategy on bioeconomy: Towards a knowledge based sustainable innovation. New Biotechnol. 2018, 40, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lancker, J.; Wauters, E.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Managing innovation in the bioeconomy: An open innovation perspective. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 90, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkus, A.; Hagemann, N.; Bedtke, N.; Gawel, E. Towards a sustainable innovation system for the German wood-based bioeconomy: Implications for policy design. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3955–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Merrill, M.; Sammalisto, K.; Ceulemans, K.; Lozano, F.J. Connecting Competences and Pedagogical Approaches for Sustainable Development in Higher Education: A Literature Review and Framework Proposal. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinha, C.; Caeiro, S.; Azeiteiro, U.M. Sustainability Strategies in Portuguese Higher Education Institutions: Commitments and Practices from Internal Insights. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waas, T.; Verbruggen, A.; Wright, T.S. University research for sustainable development: Definition and characteristics explored. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L. About the Role of Universities and Their Contribution to Sustainable Development. High. Educ. Policy 2011, 24, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toakley, A.R. Globalization, Sustainable Development and Universities. High. Educ. Policy 2004, 17, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadeeva, Z.; Mochizuki, Y. Higher education for today and tomorrow: University appraisal for diversity, innovation and change towards sustainable development. Sustain. Sci. 2010, 5, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Educational Organizations as Loosely Coupled Systems. Adm. Sci. Q. 1976, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maassen, P.; Stensaker, B. From organized anarchy to de-coupled bureaucracy: The transformation of university organization. High. Educ. Q. 2019, 73, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, R. Delving into social entrepreneurship in universities: Is it legitimate yet? Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2019, 6, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colyvas, J.A.; Jonsson, S. Ubiquity and Legitimacy: Disentangling Diffusion and Institutionalization. Sociol. Theory 2011, 29, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Incorporation and institutionalization of SD into universities: Breaking through the barriers to change. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. (Ed.) Crafting an analytical framework: Three pillars of institutions. In Institutions and Organizations; Sage: London, UK, 2008; pp. 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker, L.G. The Role of Institutionalization in Cultural Persistence. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1977, 42, 726–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krucken, G.; Meier, F. Turning the university into an organizational actor. In World Society and Organizational Change; Drori, G., Meyer, J.W., Hwang, H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolbert, P.S.; Zucker, L.G. Institutional Sources of Change in the Formal Structure of Organizations: The Diffusion of Civil Service Reform, 1880–1935. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, S.R.; Tolbert, P.S. Institutionalization and Structuration: Studying the Links between Action and Institution. Organ. Stud. 1997, 18, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A.T. The Constitution of Society. Outline of the Theory of Structuration; Polity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sewell, J.W.H. A Theory of Structure: Duality, Agency, and Transformation. Am. J. Sociol. 1992, 98, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuenfschilling, L.; Truffer, B. The structuration of socio-technical regimes—Conceptual foundations from institutional theory. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolbert, P.S.; Zucker, L.G. The institutionalization of institutional theory. In Studying Organization. Theory and Method; Clegg, S., Hardy, C., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1999; pp. 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M. The Politics of Environmental Discourse; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Qualitative case studies. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 443–466. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diario da Republica. Resoluçao de Conselho de Ministros, No. 163/2006. Diario da Republica 2006, 1, 8316–8327. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Innovating for Sustainable Growth. A Bioeconomy for Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Portuguese Government. Estrategia, de Investigaçao e Inovaçao para Uma Especializaçao Inteligente. 2014. Available online: https://www.portugal2020.pt/sites/default/files/enei_versao_final_0.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- Agencia Para O Desenvolvimento E Coesao, I.P. Portugal 2020: Objetivos, Desafios e Operacionalizaçao. 2014. Available online: https://www.portugal2020.pt/sites/default/files/portugal2020objetivos_desafios_19_dez_14.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- Comissao de Coordenaçao e Desenvolvimento Regional do Centro. RIS3 do Centro de Portugal. Estrategia, de Investigaçao e Inovaçao para Uma Especializaçao Inteligente. 2014. Available online: https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/documents/20182/232332/PT_Centro_RIS3_201402_Final.pdf/78c792ce-e32d-4e50-986b-ec8ea8df656e (accessed on 26 October 2019).

- University of Aveiro. Plano Estrategico Da Universidade De Aveiro Para O Quadrienio 2019–2022. Available online: https://www.ua.pt/en/about-us (accessed on 3 November 2019).

- University of Aveiro. Plano De Atividades Da Universidade De Aveiro. Available online: https://www.ua.pt/en/about-us (accessed on 3 November 2019).

- University of Aveiro. University of Aveiro. Available online: https://issuu.com/universidade-de-aveiro/docs/brochura_ua_ingl (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- Times Higher Education. World University Rankings 2020. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2020/world-ranking#!/page/0/length/25/locations/PT/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- Quacquarelli Symonds. QS World University Rankings 2020. Available online: https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2020 (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- Maina, S.; Kachrimanidou, V.; Koutinas, A. A roadmap towards a circular and sustainable bioeconomy through waste valorization. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2017, 8, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.; Pashby, I.; Gibbons, A. Effective university-industry interaction: A multi-case evaluation of collaborative R&D projects. Eur. Manag. J. 2002, 20, 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Stratfor. Can Portugal Remain the Eurozone’s Anomaly? Available online: https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/how-much-longer-will-portugal-remain-eurozones-anomaly-europe-economy-elections (accessed on 22 November 2019).

- Foray, D. In response to ‘Six critical questions about smart specialization’. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 2066–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelkorn, E. Rankings and the Reshaping of Higher Education: The Battle for World-Class Excellence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Polo, F.; Sanchez-Martin, J. Teaching for a Better World. Sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals in the Construction of a Change-Maker University. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).