Abstract

The main purpose of this study was to analyze and compare the online complaining behavior of Asian and non-Asian hotels guests who have posted negative hotel reviews on TripAdvisor to voice their dissatisfaction towards a select set of hotel service attributes. A qualitative content analysis of texts which relied on manual coding was used while examining 2020 online complaining reviews directed at 353 UK hotels and posted by visitors originating from 63 countries. The results from the word frequency analysis reveal that both Asian and non-Asian travelers tend to put more emphasis on Booking and Reviews when posting complaints online. Based on a manual qualitative content analysis, 11 different major online complaint categories and 65 sub-categories were identified. Among its important findings, results of this study show that non-Asian guests frequently make complaints which are longer and more detailed than Asian customers. Managerial implications and opportunities for future studies are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Recently, advanced technologies like the Internet and Web 2.0 applications have led to the rise of a wide range of consumer-generated media platforms, which, in turn, have allowed word-of-mouth (WOM) communications to reach untold numbers of people within electronic communities and virtual networks. This new manifestation, which has been dubbed “electronic word-of-mouth” (eWOM) [1], has become a widely trusted source of information—which usually comes in the form of online consumer reviews. Procurement of services is one area where such networks have found particular favor, as the intrinsic intangibility of services often poses valuation challenges for customers [2]. In relation to products and services connected with the tourism and hospitality industry, online consumer reviews have a very strong influence on how consumers retrieve information, make evaluations, and reach decisions to make purchases [3]. Literature has demonstrated that nearly 95% of consumers read online reviews before making purchase decisions, and more than one-third of customers rely on opinions expressed in reviews when selecting a hotel online [4].

In a world of advanced mobile communities (e.g., TripAdvisor App, Agoda App), consumers are relying heavily on online reviews for their online booking decisions. Online reviews and consumer ratings have been found to be the most trusted sources of information other than advice from friends, peers, or family [5,6]. Previous studies on online consumer reviews in the hospitality and tourism industry have highlighted the importance of the role played by online reviews in relation to online booking intentions [7,8], consumer decision-making [9], consumer attitudes [10,11], and perception of trust [12]. Research on online consumer behavior has demonstrated that negative reviews hold more sway than positive reviews; therefore, consumers will give more weight to negative information when making judgments or performing decision-making tasks [13]. An example of this can be seen in a study by Casaló, Flavián, Guinalíu, and Ekinci (2015) on travelers’ perceived usefulness of online reviews. The results show that the travelers find negative online reviews more useful than positive ones. Nevertheless, although the significance and the influence of online reviews is well recognized, the important question of how to understand online complaining behavior within the context of different cultural backgrounds still remains, with only a few researchers focusing on the relevant factors thus far.

Customer dissatisfaction and consumer complaining behavior were quick to draw attention from the researchers of and service providers in the hospitality industry. Although consumer complaints do give hoteliers the opportunity to improve their marketing programs in ways that can enhance customer satisfaction and hotel profitability, they can also impact the hotel’s reputations and potentially do great damage to the company [14]. Thus, we duly recognize the importance that must be attached to proper and applicable understandings of consumer complaint behavior. Literature has argued that complaint behavior may manifest itself differently on account of the distinct norms that are inherent to varying cultures [15]. For example, Ngai, Heung, Wong, and Chan (2007) examined the different attitudes Asian and non-Asian hotel guests held towards complaining behavior. The study found out that Asian guests were less likely to complain directly to the hotels for fear of “losing face”, preferring rather to take non-direct action, such as through negative word-of-mouth. Yuksel, Kilinc, and Yuksel (2006) carried out a study to explore whether consumer complaint attitudes and behaviors differ according to nation, taking Turkey, the Netherlands, Britain, and Israel as examples. The results showed that British travelers were more likely to talk to a supervisor when seeking resolution to the problem than Dutch and Israeli guests were. The Dutch and Israeli tourists, however, were more likely to demand manager interventions than to communicate their dissatisfaction to general staff members. Thus, the study was able to identify distinct patterns of complaining at hotels when comparing different cultures.

While consumer complaining behavior has received some previous empirical attention in the tourism and hospitality industry, only a few researchers have conducted cross-cultural studies in this area based on data acquired through text mining. Examples of these include Au, Buhalis, and Law (2014), who employed text mining to acquire data on Chinese and non-Chinese customers in an attempt to examine the relationship between culture and other factors which may affect intentions to post online complaints. Stringam and Gerdes Jr (2010) examined the link between textual data and the corresponding ratings which travelers assigned to the hotels. Additionally, Barreda and Bilgihan (2013) utilized the text mining method on TripAdvisor posts to determine factors that may affect brand image. The present study applies an approach which has been adopted by a number of more recent studies in order to acquire a targeted set of textual data. The data, which pertain to the experiences of travelers who had recently spent time in London, England, are subjected to analysis for the purpose of developing a more in-depth understanding of the cross-cultural complaining behavior of tourists posting online.

The present study is significantly different from its predecessors for the following reasons: (i) Some of the previous work (e.g., Ngai et al., 2007; Yuksel et at., 2006) conducted investigations of guests’ complaining behavior by performing analyses of data collected by way of the traditional Likert scale questionnaire. Presently, all factors of discrepancy between these two approaches cannot be fully appreciated; however, more obvious ones pertain to the size and scope of the sample and the fact that one of the data sets is solicited while the other is volunteered. (ii) The previous studies which did utilize text mining to acquire data (e.g., Au et al., 2014: n < 400 reviews; n < 40 hotels) were limited to relatively small sample sizes and narrow scopes in terms of hotel category. The present study, however, analyzes 2020 online complaints posted by travelers of 63 nationalities about 353 hotels in the UK, and covers the full range of star-ratings. (iii) This is the first attempt to analyze and compare the possible differences in the online complaining behavior patterns of travelers from different cultural origins (i.e., Asians and non-Asian) by utilizing a manual qualitative content analysis approach.

With consideration given to (1) current gaps that exist in related research, (2) the popularity and usefulness of data mining, and (3) the advantages of employing a manual qualitative content analysis approach, both the generic and specific purposes of this study are:

- i.

- To identify the antecedents of the most frequent complaining terms/words used by travelers sharing their complaints within online travel communities;

- ii.

- To investigate which online complaint attribute categories influence customers’ overall dissatisfaction; and

- iii.

- To examine how attitudes towards these complaint attribute categories vary among members of different cultural origin (i.e., Asian and non-Asian).

The present study uses two approaches to carry out the analysis. Firstly, it attempts to identify the most frequent complaining terms/words used by Asian and non-Asian travelers, according to the premise that terms used most often are most important [16]. The second step involves the analysis of the types of complaints found in the online hotel reviews on TripAdvisor in order to identify potential differences in complaining behaviors exhibited by Asian and non-Asian guests in regards to specific hotel service attributes.

The current paper attempts to contribute to tourism literature by identifying different patterns in online complaining behavior exhibited by travelers of different cultural background. Since previous studies have given less focus to this topic and its surrounding questions, the hopes are that the results will provide hotel managers with new insights on how members of different cultures perceive different service categories. With consideration given to certain inherent differences in their cultural attributes, Asian and non-Asian hotel guests are compared to determine whether dissimilarities in expectations and/or behavior would appear. According to Hofstede (1980) [17], cultural differences can be categorized into four dimensions: power distance, individualism-collectiveness, masculinity-femininity, and uncertainty avoidance. He also further maintained that Asian countries tend to be more collective in orientation, while non-Asian ones put more emphasis on individualism. Becker (2000) [18] argued that Asians tend to be more conformist, more cautious when responding to uncertain situations, and more reserved in expressing emotions. In terms of complaining behavior, Asians were also considered less likely to engage directly for fear of potentially losing face. Non-Asians, on the other hand, felt that complaining was a responsibility of sorts, believing that it could lead to improvements. In the era of the Internet and social media, however, such tendencies may not be as they once were; thus, the hopes are that the results of the present study will help shed light on the issue.

In this study, the content analysis technique is applied to the data retrieved from the targeted online travel community (i.e., TripAdvisor). Online complaining reviews are textual data consisting of the reviewers’ subjective opinions and perspectives; therefore, a content analysis technique that incorporates a coding scheme based on a subjective evaluation of the content is selected. The approach is regarded as appropriate for this study for the following three main reasons: Firstly, it is an adaptable tool for analyzing text-based data [19], applicable in situations as these, where the researchers are required to read through all the text while interpreting and coding them subjectively [20]. Secondly, unlike with the numerical data from Likert scale questionnaires, the textual data collected in this study may express additional information through the tone of the communication. Thirdly, content analysis allows the researchers to get access to the recommendations made on service quality and can thereby hopefully allow the researchers to identify motives behind the complaints [21].

The study begins by illustrating the theoretical background, then moves to describe the methodology and results. Implications and future research suggestions and recommendations are discussed at the end.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cross-Cultural Complaining Behaviors

Literature on cross-national differences in consumer behavior has shown that cultural differences can have substantial effects on consumers, even to the degree that the same product or service may be perceived differently in concomitant with the respondents’ culture of origin [22]. Moreover, the cultural background and language differences of customers may produce dissimilarities in perceptions of and/or reactions to products and services [23]. Previous studies relating to cultural differences in the hotel industry can be segmented into four areas of focus [23]: (1) differences in perceptions of service [24]; (2) differences in expectations for service delivery [15,25,26,27,28]; (3) differences in service demand emphasis [29]; and (4) complaint differences understood according to the moderating role of language and culture [14,30,31]. The following review of literature related to cross-cultural tourist behavior is presented according these four categories.

Cultural differences can lead to different perceptions of service quality, willingness to repurchase, and the manner, quality, and frequency of recommendations made to others for those services; as such, significant differences exist when it comes to experience evaluations [23]. For example, when Hsieh and Tsai (2009) aimed to clarify cognitive differences of tourists from different cultural areas with respect to service quality (specifically, hotel service perceptions), their results showed that Taiwanese and American guests exhibited different cognitions toward hotel service quality in consequence of cultural differences. Taiwanese were more concerned about overall service quality than American consumers. Furthermore, Taiwanese and American consumers held significantly different views when it came to the dimensions of reliability, reaction, assurance, and empathy. This was interpreted to mean that Taiwanese consumers were more concerned about these four dimensions than the Americans were [24].

Travelers coming from different cultures have also been show to hold significantly different expectations [23]. When Wang et al. (2008) assessed Chinese tourists’ perceptions of the service quality at UK hotels, it was found that Chinese tourists held higher expectations for the services on account of the fact that the UK is a more developed country. In terms of tangible attributes, most Chinese tourists preferred hotels with modern decorations and furnishing; however, many hotels in the UK had styles that were too old to be appealing. Consequently, the discrepancy between expectation and outcome had an obvious effect on the Chinese tourists’ experience and resulted in negative consumer emotions [15]. Earlier on, Mok and Armstrong (1998) argued that tourists from different cultures foster different expectations with respect to hotel service quality. Their results revealed that for items such as hotel facilities, employee appearance, hotel services, and employee courtesy, travelers from the UK received the highest overall expectation scores, followed by tourists from USA, Australia, Taiwan, and Japan, respectively. The Japanese tourists not only held the lowest expectations for these tangibles, but also exhibited the lowest expectations with respect to the empathy dimension [28]. Mattila (2000) investigated the way in which the cultural-based biases of Asians and Westerners affected the evaluation of service encounters in hotel and restaurant settings. The findings suggested that customer evaluations of service encounters may indeed be culturally bound, with Asian travelers giving significantly lower ratings to the service providers in both scenarios (hotel check-out and fine dining). When comparing perceptions of fairness and levels of satisfaction among members of two distinct culture groups (USA: individualistic culture; and Korean: collectivist culture) with respect to hotel room pricing, the results indicated that US consumers seemed to prefer equitable outcomes over better or worse pricing [26]. Moreover, offering information on the hotel’s pricing policy had a more positive impact on Korean travelers than their American counterparts. In another study measuring service quality and customer satisfaction at hotels in Malaysia, Malaysian, Asian, and non-Asian hotel guests were the subjects of comparison. While none of the guests found the service quality to meet their expectations, the Asian and non-Asian guests were more satisfied than the Malaysian ones, who had the lowest expectations and perceptions out of the three [27].

Cultural differences may inspire different types of demands from travelers during their stays at hotels [23]. Kuo (2007) purposed to uncover differences in the perceived importance of employee service attitudes and satisfaction with services amongst customers from America, Japan, and Taiwan. The study found a significant difference in the perceptions of customers from different nationalities [29]. For example, American travelers emphasized elements such as employees being able to solve customer problems; they were also dissatisfied with the service when employees lacked an adequate command of English. Meanwhile, Taiwanese customers stressed the importance of employees treating customers politely regardless of their attire. They felt that employees treated them unfairly because they expected to get tips from well-dressed customers. In their study, the researchers concluded that:

“American tourists are easy to satisfy regarding employee services; Japanese tourists have the highest expectations and are very hard to satisfy; Taiwanese require a fairly high standard of service attitude.”[29] (p. 1079)

Complaint patterns have been shown to be completely different from culture to culture, especially when encountering unfair services [23]. Huang et al. (1996) utilized the concept of national character to explain differences in the complaining intentions of guests from Japan and the US. The results reported that American guests were more likely to stop patronizing the hotel, complain to hotel management, and warn family or friends than the Japanese respondents—who were more likely to take no action in response to unsatisfactory services [14]. In such cases, a partial explanation on differences in behavior has been developed in the research of Ngai et al. (2007), who concluded that Asian guests were less likely to complain to the hotel management for fear of losing face and were also less familiar with the channels for making complaints. Asian guests, however, were more likely to engage in private complaining actions, such as the spreading of negative word-of-mouth to friends and relatives about their bad hotel experiences. In another study, Yuksel et al. (2006) explored similarities and differences in the complaining attitudes and behaviors of hotel customers from Turkey, the Netherlands, Britain, and Israel. The results depicted more differences than similarities in the complaining behaviors of hotel customers from these countries. Other research has corroborated that upon the occurrence of a service failure, customers from the West were more likely to complain than those from the East [32]. For instance, although Japanese customers gave lower ratings to superior services, they were found to be more forgiving of inferior service than US customers. A review of the preceding literature has made it quite evident that different cultural backgrounds and languages can result in differences in complaining behaviors. However, there has not yet been a comprehensive qualitative analysis conducted on the potential differences in the online complaining behavior of Asian and non-Asian travelers who have opted to use online travel websites (e.g., TripAdvisor) to voice their grievances towards hotel service attributes. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap, trusting that it will be an important basis for formulating business strategies and future studies. Appendix A presents cultural differences within the hotel industry according to a four-segment model adopted from Schuckert et al. (2015). These include perception difference, expectation difference, emphasis difference, and complaint difference.

2.2. The Significances of TripAdvisor

There are several reasons why this study chooses TripAdvisor to serve as the source of the research data; namely: (i) TripAdvisor has been widely adopted by scholars worldwide as a data source for conducting research, especially for those conducting research related to tourism and hospitality [33]; (ii) TripAdvisor is one of the most influential eWOM sources in the hospitality and tourism context when it comes to consumer opinion platforms [34]; (iii) TripAdvisor aggregates online consumer-generated reviews from hotels all over the world and cooperates with other travel sites partners, such as Agoda.com, Expedia.com, Booking.com, Trip.com, and many more, thus providing a great wealth of information for researcher to explore [35] (p. 2–4); (iv) finally, for reasons which will be discussed below, TripAdvisor is considered to hold a high level of representativeness for the topic currently under consideration.

TripAdvisor is one of the world’s largest online travel communities for tourists seeking advice on where to stay and what to do from people who have first-hand experience on the destinations of interest [36]. Launched in the year 2000, TripAdvisor is a space that encourages unbiased traveler reviews on hotels, restaurants, and attractions [37]. It is also recognized to be the most popular independent consumer review site on the web [38]. The site provides access to a staggering 300 million reviews and opinions which have been submitted by travelers who have trekked the globe [39]. It covers 4 million businesses and properties related to accommodations, with hotels, B and Bs, and specialty lodgings accounting for 810,000 units [33]. Moreover, TripAdvisor operates in 49 markets and has more than 415 million monthly visitors [40]. On TripAdvisor, tourists are allowed to provide an overall rating for a hotel’s service using a five-star rating system, while also providing detailed comments about their experiences [41]. Additionally, TripAdvisor offers very clear hotel class segmentation information for every hotel being reviewed. To accomplish this, it utilizes a segmentation scheme that awards hotels with “crowns”, which have a value of 5 for luxury hotels, 4 for above average hotels with some outstanding features and a broad range of services, 3 for full-service hotels, 2 for mid-market economy hotels, and 1 for budget traveler hotels [42].

Extracting data from TripAdvisor provides multiple benefits. First, TripAdvisor allows researchers to collect huge data sets from its user-generated reviews, and thereby achieve high levels of external validity [43]. These data, which are aggregated from a large number of people, can be obtained at a considerably low cost [34]. Second, TripAdvisor offers various language interfaces and provides such supplementary information as the reviewer’s nationality. This allows for the inclusion of national-level information and the grouping of subjects based on such considerations as country of origin and cultural background [44]. Finally, TripAdvisor provides a detailed client reviews of hotels with a rating scale that ranges from “terrible” (1 star), on the low end, to “excellent” (5 stars) on the high end [45]. This allows the researchers to learn more about the role that each attribute has played in shaping the customers’ overall satisfaction with respect to each of the hotel experiences (see [46]). The advantages of using online travel community sites as tools for analyzing customer comment behavior have been previously discussed and are thus applied to this present study with the intent of identifying patterns of complaining behavior exhibited by Asian and non-Asian guests who were discontent with the quality of the hotel services they were provided.

3. Research Design and Process

This current study comprised three major stages, namely: (1) the development of a pre-built framework, (2) the extraction of data, and (3) the preparation and coding of the extracted data. In order to hone in on the targeted attributes and items which would potentially impact hotel guest satisfaction, a literature review was conducted to develop a pre-built framework. A total of 10 hotel attributes and 51 items were initially identified and developed on. These were subsequently included in the coding system of categories.

To understand the online complaining behavior of guests from different cultural origins, qualitative analyses were adopted, including a simple word frequency analysis and a manually-implemented qualitative content analysis. The details of each stage are described below.

3.1. Pre-Built Framework through Literature Reviews

To determine the target attributes and items that have impacts on hotel customer satisfaction and develop the underlying structure of the study, a comprehensive round of literature reviews was conducted. The reviews included literature on: customer experiences with budget hotels [47], customer satisfaction with 4- and 5-star hotels [48], customers’ opinions on the service quality at small and medium hotels [49], customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction with full-service hotels, limited-service hotels, and suite hotels with/without food and beverage services [20], customers’ positive/negative experiences with hotel cyberspace communication [19], customer perceptions of staying at the hostel [50], and customer online complaining behavior [21]. This part of literature generated 10 hotel attributes and 51 items, as shown in Table 1. The attributes and items gleaned from the aforementioned studies were treated as a single set, which was subjected to a qualitative content analysis, as detailed in the section on methodology. The refined attributes and items provided the basis for a pre-built framework and a guideline for coding the negative comments. However, modifications were applied as necessary so that the materials would appropriately align with the study’s purpose of identifying online complaining patterns exhibited by members of different cultural origin (i.e., Asian and non-Asian).

Table 1.

Attributes and items influencing on customer (dis)satisfaction.

3.2. Sample Credibility

In consideration of the large amount of positive attention that tourism scholars have been giving to online reviews as information sources, this study attempted take advantage of the same for the purpose of conducting its analysis (see [43]). Data collection was conducted in November of 2018. At that time, 353 hotels were randomly selected from a population of 1086 listed on the TripAdvisor site for the market in London, UK (London was chosen simply because it is a major tourism destination with a big number of hotels rather than for any empirical or metrological reasons [51] (p. 763)) [52]. The hotels were ranked from 2- to 5-stars based on the British hotel rating system. To ensure the credibility of the sources and size of the sample, this study restricted the subject hotels to those with more than 200 reviews. To ensure efficiency and proper representation of complaint data for each of the selected hotels, a maximum of 20 of the most recently posted negative reviews with details of the complaints (starting from the lowest ratings of 1-star to 2-stars) were extracted for analysis. When a guest has given an overall rating of 1- or 2-stars, that rating is designated as “negative” in the TripAdvisor reviews system [16]. Reviews without textual content or information on the traveler’s nationality (demographic information) were excluded.

3.3. Data Extraction

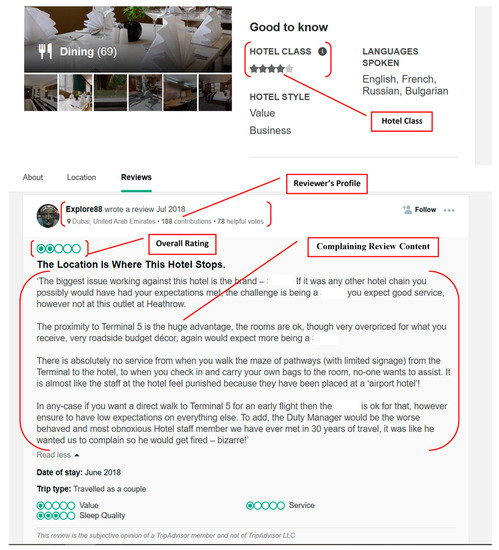

All of the online reviews that were selected from TripAdvisor comprised textual data. The extraction of such textual data, referred to as “textual mining”, has been described as “the process of extracting useful, meaningful, and nontrivial information from unstructured text to overcome information overload” [20] (p. 60). To get deeper insight on the data, a mixed approach was applied in the present study. First, a qualitative method, including grounded theory and content analysis, was used for the initial analysis of the data. The researchers read through all the online-review text and interpreted and coded it subjectively according to a consistent coding schema. Every single review was manually extracted in the form of textual data along with the reviewer’s demographic information, as shown in Figure 1. In total, 2020 valid online complaining reviews were retrieved for the analysis.

Figure 1.

Textual review of complaint for the data analysis.

Among the 2020 complaining online reviews, the total sample size for the analysis represented 63 nationalities. These reviews were classified as belonging to Asian or non-Asian travelers based on regional markings, followed by UN regional and national statistics classification [53]. The physical boundaries of the nation state reflect the national culture behind [22]. Specifically, culture means the similar behavior of a certain group of people. Of the reviewers, 74.03% (N = 1503) were non-Asian travelers, mainly originating from England (N = 678, 33.56%), America (N = 258, 12.77%), Australia (N = 227, 11.24%), Canada (N = 63, 3.12%), Ireland (N = 42, 2.08%), New Zealand (N = 33, 1.63%), and other (N = 198, 9.8%). Asian travelers made 25.7% (N = 517) of the comments and originated from the United Arab Emirates (N = 99, 4.90%), Singapore (N = 81, 4.01%), Hong Kong (N = 62, 3.07), China (N = 30, 1.49%), India (N = 30, 1.49%), Thailand (N = 30, 1.49), Malaysia (N = 23, 1.14%), and other (N = 166, 8.22%). Table 2 details the supplementary dataset.

Table 2.

Summary of the dataset.

3.4. Data Preparation and Coding

First, each negative review was retrieved manually by copying the information from the TripAdvisor source to a Word file (for textual data) or Excel file (for numerical data; e.g., ratings). The textual data were unstructured data which needed to be transformed into meaningful knowledge via a decoding mechanism [54]. In order to convert the unstructured textual content into structured data, qualitative content analyses were performed (see [55]).

Second, to code the data, a pre-built framework developed based on the literature reviews was utilized. After that, the qualitative content analysis of each text relied on the performance of manual coding. This was accomplished by creating coding categories that explained how the comments were developed. To avoid overlapping themes and reduce the ambiguity of the content, coding categories and coding variables were added, removed, or merged at the discretion of the researchers, following discussions which gave consideration to the pre-built framework. In order to reduce the impact that biases might have on coding decisions, the data were categorized by two independent coders, each of whom organized the data according to various complaint attributes, items, and connotative meanings. Both coders independently coded the same dataset using the same pre-built framework as a guideline for developing the scheme.

This study opted to assign codes manually in order to capture the idiosyncrasies of the reviews and account for nuances that would otherwise be neglected [56]. Moreover, by adopting a manual approach, the researchers benefited from the strong interpretational power that is derived from a pre-built framework [57]. Inherently, online complaining behavior is multifaceted in nature, as travelers from different cultures of origin may use different words, expressions, or tones (such as sarcasm) to express their sentiments. It was thus very difficult to conduct a pre-analysis to delineate a set of words or expressions that should receive specific attention or weighting. Therefore, the researchers decided instead to manually code the dataset in order to avoid the shortfalls that analytic tools would inevitably create while working to identify each aspect of the online complaining behaviors [56].

Then, through the qualitative content analysis, a system of categories was created [58]. The categories were constructed according to the denominations of hotel attributes and items which have been shown to have an impact on customers’ (dis)satisfaction in previous studies. For example, the statement, “What’s more, the toilet cover was very dirty when we checked in,” was assigned to the “Cleanliness” category and itemized as “filthy toilet”. Another example from the Cleanliness category which was itemized as “bedroom uncleanliness” states: “The room just felt badly cleaned and dusty, especially the bed counterpane.” If categorization differences occurred between coders or there were discrepancies with the pre-built framework, consensus on the matter was reached through discussion [21].

After considering the coding schemes in previous discussions (10 hotel attribute categories and 51 items) as well as the results from manual content analysis, the final classification system for describing the content of the text was created. During this stage, two sub-category complaint attributes from the pre-built framework were removed, as they were deemed to be redundant based on the results of the coding work. Therefore, the final framework that was developed based on the literature review was revised to include 10 hotel attribute categories and 49 items. Several rounds of manual coding were performed to code the data using Nvivo 11, which is one of most preferred qualitative content analysis tools [59,60]. This analysis tool has been utilized as an instrument for discourse analysis, grounded theory, conversation analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, content analysis, and more [19]. By following this process, the researchers were able to inductively and/or deductively determine the principal factors leading to the complaints [21].

Finally, to ensure reliability and overcome the possible biases of a single coder, this study followed the approach of Lombard, Snyder-Duch, and Bracken (2002) [61] and Gerdt et al. (2019), making use of two independent coders. Inter-coder reliability was verified by calculating the percentage of agreement, namely: “the percentage of all coding decisions made by pairs of coders on which the coders agree with the values of 0.00 (no agreement) to 1.00 (perfect agreement)” [61] (p. 590). To ensure consistency in the coding, this study followed the Cenni and Goethals (2017) two-step inter-code reliability test. A preliminary inter-code reliability test was conducted after coding 5% of both full sets of coded reviews, then a second reliability test was performed after coding an additional 10% of the total samples. The results showed that both coding grids were > 90%, which was judged sufficient (see Table 3). A reliability standard for each code in the framework developed by the two researchers was also calculated [58]. When considering each category and sub-category, the inter-coder reliability remained above > 90%, demonstrating high levels of agreement.

Table 3.

Assessing inter-coder reliability test between Coder A and Coder B.

3.5. Data Analysis

The importance of the words travelers used when making complaints was analyzed in two ways. To address the first of the study’s objectives, complaining words were identified based on frequency, subjected to discussions, and then categorized according to the number of occurrences. In this process, a simple words frequency analysis was conducted without consideration given to the different cultural backgrounds of hotel guests (Asians/non-Asians). This technique acts according to the premise that words used more frequently address issues of higher importance [16].

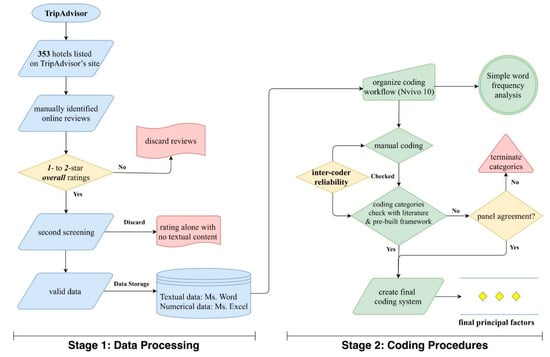

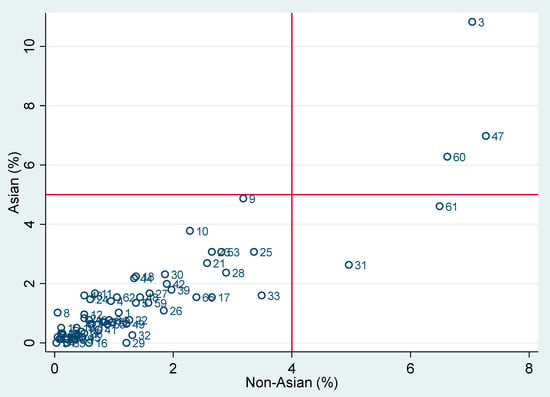

Second, factors or categories affecting the online complaining behavior of travelers from different cultural backgrounds were identified and examined. The coding scheme and online complaint elements were carefully checked and refined. Through this process, an additional complaint attribute category (i.e., online review) and 16 complaint attribute sub-categories were discovered (details are in Table 4). The additional category and sub-categories had received little attention in previous studies. Once the final coding scheme and online compliant elements were sorted into 11 different major online complaint-attribute categories and 65 different complaint-attribute sub-categories, the instances and percentages of each situation that instigated travelers to make online complaints were calculated. In each case, a comparison was made between Asians and non-Asians in order to ascertain case frequency and percentage. From here, the frequency and percentage of each category was calculated by dividing the case observation count by the total numbers of cases for the category. Figure 2 summarizes the research process.

Table 4.

Online complaint attributes from travelers complaining on online platforms.

Figure 2.

Research process.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. The Antecedents of Travelers’ Most Frequent Terms/Words within Complaints

The word frequency analysis highlights the issues of greatest concern within the online complaining reviews (Table 5). Based on the analysis, it became clear that “room”, “hotel”, and “staff” were the most significant issues for sampled guests, as they were the top three most frequent words found within the reviews. While ignoring the adjectives, the word frequency analysis went further to include the following topics of complaint: bookings, reviews, servicing, breakfasts, timings, beds, checking, location, bathroom, managers, cleaning, reception, showers, doors, floors, food, and bars (see Table 5). Of these, travelers tended to emphasize service and breakfast more frequently within the postings. Similar patterns also can be found for beds, bathrooms, cleaning, and showers, which is consistent with the findings of Stringam and Gerdes Jr (2010). In these cases, the frequency of the words increases when lower ratings are assigned to the hotel. Unlike what has been seen in the previous studies, in the present study, issues related to bookings and reviews appeared the most frequently within the topics of complaint (top five). In this case, we assumed that the travelers may have read the online reviews prior to booking the rooms, and upon arrival found that the actual situations did not meet the expectations that the reviews had inspired. This may suggest that hotels are failing to deliver consistent services—at least to the point that the comments of some customers are not adequately agreeing with successive customers’ experiences. Thus, hotel operators should keep themselves up-to-speed with the reviews as much as possible and work to ensure that customers’ expectations will be met. Also of note, the word “managers” appeared quite frequently in complaining reviews, indicating that guests are expecting management to be involved in service recovery [16].

Table 5.

Simple online complaining word frequency among all the travelers (top 21).

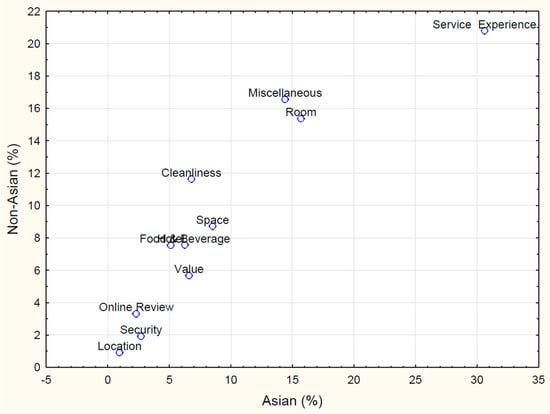

A major challenge for word frequency is that the context of the word itself is not clear [51]. Therefore, the qualitative content analysis was applied to organize the data according to more specific themes and categories, which allowed the contextual meaning of the word or comment to be properly understood. In the following paragraphs, the themes/categories of online complains are identified and broken down with consideration given to the different cultural origins in question (Asian and Non-Asian). Figure 3 shows the frequency of the words used by Asian and Non-Asian hotel guests in their complaining reviews. Larger font size represents higher frequency, which is interpreted as greater importance.

Figure 3.

The frequency of the words used by Asian and Non-Asian hotel guests.

4.2. Major Classifications of Online Complaint Attribute Categories

After carefully analyzing the complaining reviews, the study identified 11 different major online complaint-attribute categories, and 65 different complaint-attribute sub-categories. Of these, 10 categories and 49 sub-categories were found in prior literature, whereas the remaining 1 category (i.e., online review) and 16 sub-categories were discussed little in the previous studies (see Table 4). The results extend the core ideas developed in traditional customer complaining behavior research by focusing on new ways internet platforms are utilized for the expression of complaints. The complaint attributes identified in the internet reviews underpin online customer complaining behavior and cover a considerable range of hotel features, such as service experience, room, hotel, cleanliness, location, value, security, space, food and beverages, online review, and miscellaneous. The specific attributes (i.e., service experience, room, cleanliness, location, space, and food and beverages) were similar to the complaint categories noted by earlier research on and about hotels in Asia (e.g., China) [21,47]. The security complaint attributes showed consistency with prior research on international hostels (located in Cambodia, Hong Kong, Australia, Korea, Thailand, and the UK) [50]. Specific achievements of the present study were made in relation to the complaint attributes of hotel, value, and online review. Table 4 shows the detailed complaint attributes of negative reviews sorted into various categories and sub-categories.

Representing 20.80% of all cases for non-Asian and over 30% for Asian guests, Figure 4 illustrates the chief importance of service experience within the complaint attribute categories. This result is consistent with a study by Au et al. (2014) that identified service quality as the dominant complaint category. From here it can be inferred that service experience represents the biggest shortfall as perceived by the guests and is a high priority for guests during their stay [21]. A sample complaint made by a guest about the service experience encountered at a hotel testifies to this:

“There is absolutely no service from when you walk the maze of pathways (with limited signage) from the Terminal to the hotel, to when you check in and carry your own bags to the room, no-one wants to assist. It is almost like the staff at the hotel feel punished because they have been placed at an ‘airport hotel’…”

Figure 4.

Complaint attribute categories differed between Asians and Non-Asians in percentage.

The room complaint attribute was the second-most prominent complaint category (revealed by its relatively high counts of > 15%) for both Asian and non-Asian customers. In this study, features pertaining to the hotel room itself rather than the supporting hotel facilities (< 8%) were specifically identified as causes for lower levels of satisfaction, thus supporting the study conducted by Zhou et al. (2014). For the hotel rooms, poor modernization or low levels of luxuriousness were the main targets of dissatisfaction by guests, making complaints in this category > 3%, the highest value in the room category (see Table 6). This suggests that guests traveling to developed countries (e.g., the UK) have higher expectations for modern decoration and furnishing than what is being offered in London. Many hotels in this market are too tired-looking to be appealing and this is obviously affecting tourists’ experiences and arousing negative consumer emotions [15]. A sample complaint highlights the sentiment:

“The room was pleasant (119) but didn’t feel luxurious, I have stayed in better ‘chain’ hotels, the toilet unfortunately had stains inside the pan, and contained an odd color disinfectant (if that what it was). The paint around light fittings in the bathroom looked unfinished and poor quality and the shower cubical felt cheap and if it would break at any time (the plastic tray was bouncy and glass panel is ill fitting)”

Table 6.

The differences between Asian and Non-Asian complaint attribute categories.

With regards the complaint attribute of space, both Asian and non-Asian guests seemed to place similar focus on the spatial limitations of the rooms (> 8%). When it comes to spatial requirements, preferences generally vary from one individual to another, however many guests traveling to London are likely accustomed to living in less-crowded city environments (as few can compare to London), thus will be unpleasantly surprised by the spatial limitations they encounter. Those who hold higher expectations for room size will experience a correspondingly lower sense of satisfaction with the room space. The posts below are examples of guests’ negative perceptions of the spatial confines they were presented with:

”The room is sized for a queen bed, then two other single beds were crammed in leaving no space between them to get in or out of bed without crawling in from the bottom of the bed…” and “…The room and the hotel and its location seemed OK. Room rather small according Asian standard. The bed side tables were different. One very small. …”

4.3. Differences Between the Online Complaining Behavior of Asian and Non-Asian Guests

Table 6 illustrates the differences in Asian and non-Asian complaint categories. In the largest complaint attribute category, Asian guests made more complaints (> 30%) than non-Asian guests (> 20%). They also made more complaints about poor customer service (10.83% versus 7.04%), poor courtesy (4.87% versus 3.18%), and poor competency (3.78% versus 2.28%). The reason for this may be attributable to the influence that service-oriented Asian cultures have on expectations (see [25]). These findings appear to be inconsistent with traditional customer complaining behavior studies [30,62], which concluded that customers from cultures with lower individualism (e.g., Asian ones) tend not to complain even when they receive poor services [62]. Offering an explanation for the phenomenon, Ngai et al. (2007) maintained that Asian guests were less likely to complain on account of a fear of “losing face”. This explanation could still hold valid with the results of the present study, considering that the interaction has shifted from a face-to-face situation to a “faceless” one (i.e., via social media). User-generated content on the Internet and social media is generally open access and the relative anonymity leads to trends in complaining behavior that are divergent from traditional patterns [21].

Although the disparity was very slight, Asian guests were also found to complain more about value than non-Asians (6.60% versus 5.67%); specifically, when it came to room price. This finding is similar to that of Mey et al. (2006), who found that that Asian travelers appeared to place a greater emphasis on value for money. With higher price expectations for quality increases [56], if the expectations are not met, the customer is left with a lower level of satisfaction. Another reason might relate to personal bias. Asians may feel that although they are paying the same price, they are receiving different treatment, as can be seen from the results that 1.99% of Asians made more complaints on the “not value for money” attribute than Non-Asians (1.89%). Such perceptions, whether based on correct interpretation or not, will result in the guest feeling as though the value was less than what they might have otherwise felt, as the following complaint seems to highlight:

“…He was so rude, just because we were Asians…” and “All the STAFFS was undeniably RACIST. So just a warning for all ASIANS trying to find value for their money surely avoid this xxxx. There are a-lot more better environment places you can stay in the area. I wish I didn’t chose them over…”

Another area where Asian guests were found to complain more often was with respect to considerations of security (2.69% versus 1.92%). Security features of hotels may be related to surrounding location or other attributes that contribute to the feeling of safety [63]. The role that location plays is intuitive in nature, with perceptions of neighborhoods or countries being safe or unsafe fostering or diminishing the sensation of security. Sensitivity to security (concerns for safety) may be stronger among Asian tourists as a result of the political instability that a number of Asian countries have experienced in the past—and research has shown that security issues are of a greater concern in less developed countries [50]. Therefore, it could be the case that Asians are bringing their own fear of unsafe environments with them on their travels to developed countries. Once they encounter certain situations that bring up thoughts of past experiences, they are left with a diminished sense of security. For others who have come from different cultures, the same circumstances could be interpreted as being of no threat to one’s personal safety (even if less than ideal). Perhaps the circumstances in the following comments could serve as an example:

“…11.30 pm where I was able to relive my youth of being near young drinkers vomiting in the street and of course that great pleasure of watching drunk people try to argue with each other!! This is not what I expect when staying in a 5 star hotel with a 5 star price! …my friend and I felt so unsafe…”

For other attributes, however, we did see the tides shift, with non-Asian guests complaining more than their Asian counterparts about both cleanliness (11.63% versus 6.79%) and the hotel (7.54% versus 5.12%). According to Hofstede (2009) [64], there are four main dimensions upon which cultures differ, including power distance, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, and uncertainty avoidance. The individualism versus collectivism dimension in particular is associated with fundamental differences in consumer behavior between Eastern and Western cultures [21,65]. Furthermore, there is a difference in spending patterns among Asian and Non-Asian populations. Non-Asian tourists were shown to be willing to spend a higher portion of their budgets on accommodation, and considered room quality (including cleanliness) to be the most influential factor in determining their overall satisfaction with the hotel [27]. When the expectations are not met, negative disconfirmation takes place due to the gap between the guests’ expectations and perceptions of service performance. Failure in the delivery of services often results in guest dissatisfaction and complaining behavior, such as negative word-of-mouth, complaints, and higher customer turnover [66]. The following complaint is an example of the type of issues that were raised with respect to the attributes of cleanliness and hotel:

“When we got to our room and checked round I found stale food on the bedside table… found a load of hairs stuck on the filter which I then removed! After running the bath when I turned on the jets black and brown bits started floating which was enough for me to get out!… Sadly disappointed! I have never stayed in a 5 star hotel with such a… it’s just such a shame that the room was a real let down and incredibly poor value for money…”

Figure 5 shows the differences in the top six negative topics raised by Asian and non-Asian guests. The topics include poor customer service, tiny room space, lack of facility maintenance, noise, poor courtesy, and bedroom uncleanliness. As the topics are all orientated towards service experience and facilities, commonalities and concurrences exist between them and previous studies which demonstrated that hotel customer complaints generally involve staff, process, and equipment [57,67,68].

Figure 5.

The differences of negative topics between Asians and Non-Asians.

5. Conclusions

This research examined complaints found in online hotel reviews (TripAdvisor) with the intention of identifying differences in complaining behavior patterns exhibited by Asian and non-Asian guests with respect to hotel service attributes. This objective was accomplished by applying qualitative content analysis on complaining reviews posted on TripAdvisor about hotels in the UK in order to compare potential differences in the behavior of the targeted groups.

Our research contributes theoretically to extant literature in the following manner. First, to the best of our knowledge, methodology-wise, this study is the first attempt to analyze data derived from textual mining by applying a follow-up qualitative content analysis. This addition helped to overcome the limitations of studies based on word frequency analysis alone. The qualitative content analysis approach proved to be advantageous, as the findings not only corroborated, but were able to go beyond the conclusions reached in previous studies by identifying authentic complaint categories in the online hotel reviews. Out of 11 categories and 65 sub-categories recognized in this study, 10 categories and 49 sub-categories were found in previous research, whereas the remaining 1 category (i.e., online review) and 16 sub-categories were unique achievements of this study. These new sub-categories include: long wait for room, housekeeping issues, wrong room type, programmed service, management issues, insufficient room facilities, woeful outside view, tired/non luxurious room, parking lot difficulties, bad-tasting food, spoilt food, low food quality standards, extra charge, privacy concerns, false advertising, and overrated hotel ratings. These results extend the core ideas developed in traditional customer complaining behavior research by focusing on the new ways Internet platforms are allowing people to voice their complaints. The results are also of use to researchers and hotel management looking to understand authentic types of customer dissatisfaction, acknowledging that identifying the real sources of the problems is crucial for the improvement of consumer satisfaction [57]. Second, this study went beyond previous research by unveiling how guest complaints vary depending on culture of origin. We demonstrated that non-Asian guests frequently make complaints that are longer and more detailed than Asian guests do. In addition, the tide of complaining behavior has moved away from traditional patterns on account of the open access people have to social media and the sense of anonymity it can provide. These findings contribute to hospitality literature by enhancing our understandings of the specific causes of complaints being made by hotel guests coming from different cultural backgrounds. These specifics can serve as actionable insight for related hotel operators and members of management. As will be discussed in the following, this study also illustrated certain managerial implications for hotel operators to take into consideration.

The results from the word frequency analysis revealed that both Asian and non-Asian travelers tend to emphasize service and breakfast more frequently when posting complaining reviews online (top 10). Other issues related to booking and reviews also appeared very frequently within the topics of complaint (top five). The occurrence of complaints is often due to discrepancies between expectations and encountered experiences. When it comes to travel and tourism, more and more people are seeking information in advance through online travel communities such as TripAdvisor. Once the travelers arrive, if their experiences fall short of what the reviews invited them to expect, feelings of disappointment set in and complaints often ensue. Hoteliers must therefore make an effort to be aware of customer praise as well as complaints, as the two can often have a circular relationship. The important thing is to maintain consistency and dependability, with publicity and advertisement that matches with reality.

By classifying online complaint attributes according to specific service categories, the results revealed that service experience is the dominant complaints category, followed by room and spatial limitation. Service experiences are reflections of the attitudes and service performances of staff members. While not expecting high-profile service styles, for guests, a simple welcome and smile has been shown to go a long way in establishing a harmonious atmosphere [38]. Basic staff facilitation, such as providing sufficient information, conducting smooth check-ins/check-outs, assisting with reservation difficulties, demonstrating responsiveness, having some social interaction with guests, providing good customer service, handling customers’ questions, and increasing the level of courtesy are all important. The category of “room” also found itself within the top three targets of complaints. These complaints occur when room facilities, equipment, decorations, bedding, amenities, and/or layouts fail to meet the minimum expectations for the room. Hoteliers can try to improve the experiences of the guests by providing comfortable bedding and pillows, sufficient amenities, and basic hardware and appliances such as safes, drawers, telephones, hair dryers, towel racks, and TVs. In terms of room décor or luxuriousness, there may be certain levels of subjectivity involved, however, managers can try to compensate for perceived inadequacies by welcoming guests with packets of cookies or a basket of fruit. For the present study, another complaint category that found itself high on the list was spatial limitation; this, however, may be a factor more inherent to the London market, where the hotel rooms have a reputation for being small [51].

When comparing complaining behavior across cultures of origins, Asian customers were found to complain more about service experience, value for money, and security, while non-Asian guests made more complaints on cleanliness and hotel. As noted by Magnini, Crotts, and Zehrer (2011), customer delight is strongly impacted by the nature of travel (domestic or international) and the culture origins (individualistic or collective cultures). In such respects, this present study supports previous literature on hotel satisfaction [27,69]. It is therefore important that managers train their first-contact employees to be familiar with potential tendencies of customers from different cultural backgrounds and to be aware of cultural differences in terms of expectations and preferences [21]. The present findings suggest that many hotels in London will need to renovate or update their facilities to if they hope to raise satisfaction levels among guests. Amenities such as quality Wi-Fi connections, parking, effective concierge services, in-house eating facilities, as well as well-maintained cleanliness both in the rooms and public areas should all be given attention for those hoping to meet the expectations of western guests. Meanwhile, Asian guests have been found to be more service-oriented; therefore, courteous customer service and kind, patient provision of assistance should quickly translate into higher levels of perceived value. It would also be beneficial for hoteliers to give greater attention to a perceived sense of security, especially for those coming from different cultural contexts. As Feickert et al. (2006) demonstrated, security has a very important relationship with cleanliness; therefore, increasing cleanliness, not only in the hotel interior but also surrounding areas as well, can help contribute to enhanced security perceptions [50].

New complaint topics emerged during the analysis stage of this study, leading to an extension of the pre-existing framework. Thus, the following complaint category and sub-categories were added: “online review”, and “false advertising” and “overrated hotel rating”. The “overrated hotel rating” complaint sub-category was among the most frequently coded complaints in the “online review” category, implying that tourists, in general, did not receive what they expected to, based on the reviews they read. An example of this can be seen in the following post, which stated: “disappointing with wonderful reviews posted, did not at all match with reviews, feel misled by other reviews”. Similar results also appeared during the word frequency analysis, with issues related to bookings and reviews listed among the most frequent complaint topics (top five). Managers should try to maintain a consistency between their online image and reality. For instance, website photos and other advertising should match up with the reality of the hotel. Importantly, hotels and online review websites should consider developing review analysis platforms based on automated text-mining. By building up these tools, hotel operators will be kept informed on issues related to customer (dis)satisfaction. Such platforms would allow managers to easily monitor threads and pin-point causes of customer (dis)satisfaction. They would also help them analyze their competitive advantages with respect to their competitors [57,70].

The code category “miscellaneous” may point to new issues arising in the realm of customer dissatisfaction for the hospitality industry. Within this category, lack of facility maintenance was the most common complaint sub-category (>6%), followed by noise, disgusting smell, extra charge, and privacy concern. Lack of facility maintenance or disrepair of in-house hardware can easily create bad experiences for guests during their stay. Managers should always ensure that facilities are fully operational before guests check-in. For instance, water pressure should be stable, A/C units should be functional, windows should open/close properly, and TVs should be operable. Noise and smells are also significant influencers in the overall customer experience. The results in the present study agree with prior studies, which have discussed the role that the five senses play in shaping customer experiences at budget hotels [47].

Several limitations that applied to the current study could be opportunities for exploration in future research. First, this study analyzed online complaining reviews which were written in English. The fact that the guests who made the reviews were able to operate in English-speaking communities may also mean that they have developed cultural understandings that diverge in some ways from guests who are not be able to communicate in English. Future research examining cultural differences could explore this further by comparing review data produced in the languages representing the country or culture the guests originate from. Second, to ensure credibility, TripAdvisor has established complex procedures to investigate whether reviews are manipulated or not [71]; however, this study still cannot be certain that the data selection did not contain fake reviews which were not identified by TripAdvisor [56]. Third, since service experience has been identified as the dominant category of complaints in this research, future studies may consider concentrating on coding service-related comments only, perhaps with reference to the SERVQUAL constructs, in order to gain insights on which specific service dimension(s) may need more attention [21]. Moreover, the reviews extracted in this study came from a single location and single platform. To generalize the results, future studies should collect data on hotels in various locations and from different information channels [57]. Furthermore, the categorized Asia and non-Asia groups were based on the reported nationalities, which may not represent their ethnic backgrounds. Finally, future research may attempt to verify the results of this study by employing measurement scales via questionnaire or survey; also, a more sophisticated statistical analysis could be applied to test the relationships within the categories and sub-categories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and P.-C.L.; methodology, R.S.; software, R.S.; validation, P.-C.L.; formal analysis, R.S. and P.-C.L.; investigation, R.S.; resources, R.S. and H.-C.C.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.; writing—review and editing, R.S., P.-C.L. and H.-C.C.; visualization, R.S.; supervision, P.-C.L.; project administration, R.S.; funding acquisition, P.-C.L. and H.-C.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I, Raksmey Sann, would like to express my very great appreciation to Shu-Wen Lan, Department of Modern Languages, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Taiwan, for her valuable and constructive suggestions during the proposal planning and methodology development of this research work. Her willingness to give her time so generously has been very much appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The following table depicts cultural differences within the hotel industry accroding to a four-segement model adopted from Schuckert et al. (2015).

Table A1.

Cultural differences within the hotel industry accroding to a four-segement model.

Table A1.

Cultural differences within the hotel industry accroding to a four-segement model.

| Topic | Title | Author | Objective | Subject | Respondent/Instrument | Hotel Segmentation | Findings | Future Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception Difference | Does national culture really matter? How service perception by Taiwan and American tourist | Hsieh and Tsai (2009) | To clarify the question: should management segment the markets according to different ‘‘cultures’’, serving the target consumers with the minimum ‘‘cultural shock’’ and providing the most appropriate service for consumers from different nations? | Taiwanese and American consumers | 216 questionnaires | International tourist hotels of Taiwan | Taiwan consumers and American consumers have different cognition toward international tourist hotel service quality due to their cultural difference. The differences are most pronounced in the perceptual categories labeled ‘‘Assurance’’, ‘‘Tangibles’’, ‘‘Reliability’’, ‘‘Reaction’’ and ‘‘Empathy’’. Cultural differences do influence consumer behavior. | Future research can investigate effect and causality of ‘‘national culture dimension’’ and ‘‘service quality dimension’’ and further expand the theory. |

| Expectation Difference | Cultural perspectives: Chinese perceptions of UK hotel service quality | Wang et al. (2008) | To assess Chinese tourists’ perceptions of the UK hotel service quality, and to analyze the role of Chinese culture in influencing their expectations and perceptions | Chinese Tourists | 46 questionnaires | UK hotels | Leisure tourists’ expectations are significantly different from those of business travelers. Leisure tourists attach more importance to attributes such as location, bathroom, facilities, quality of personal items, service at restaurant, employees being helpful and courteous. Business travelers care more about price, internet, communication facilities, efficient services, and employees’ being able to provide useful information. | Future study requires a larger sample size with more sophisticated statistical analysis, and also additional emphasis on the price/value relationship for hotels themselves, and the hotel category. |

| Expectation Difference | Expectations for hotel service quality: Do they differ from culture to culture? | Mok and Armstrong (1998) | To examine such expectations in the cross-cultural context, including tourists from the UK, USA, Australia, Japan, and Taiwan | UK, USA, Australia, Japan, and Taiwan | 325 questionnaires | Hong Kong hotels | Hotel guests expect that whatever was promised should be delivered. Tourists from different cultural backgrounds have different expectations of hotel service, rooms, and other attributes. | More researchers will either replicate this with a larger sample or extend it to more cultures based on types of tourists (leisure, business) to enhance the understanding of international customers. |

| Expectation Difference | The impact of culture and gender on customer evaluations of service encounters | Mattila (2000) | To close this gap by investigating culture-based biases in the evaluation of service encounters in a hotel and restaurant setting | Western travelers and Asian travelers | 149 questionnaires | First-class hotels in Singapore | Westerners and Asians evaluated the service provider’s performance in a different manner. The service providers’ performance evaluations were consistently higher with Western travelers than with their Asian counterparts. | Future research is clearly needed to supply more stringent tests of our reasoning, and the dimensions of culture should be measured. |

| Expectation Difference | A cross-cultural comparison of perceived fairness and satisfaction in the context of hotel room pricing | Mattila and Choi (2006) | To investigate how two factors, price outcome (worse/same/better price) and information on the hotel’s pricing policy, influence perceived fairness and satisfaction judgments of customers from two different cultures—USA (Western, individualistic culture) and South Korea (Eastern, collectivist culture) | American and Korean travelers | 591 questionnaires | Washington, DC and Seoul, Korea airports | US consumers seem to prefer equitable outcomes to better or worse price. Moreover, offering information on the hotel’s pricing policy had a more positive impact on Korean travelers than their American counterparts. | The sampling procedure limits the generalizability of the results. Data came from two samples (US and South Korea), and hence, replications across other cultural groups will be needed. |

| Expectation Difference | Measuring service quality and customer satisfaction of the hotels in Malaysia: Malaysian, Asian, and Non-Asian hotel guests | Mey et al. (2006) | To assess the expectations and the perceptions of service quality dimensions towards the hospitality industry in Malaysia from the hotel guests’ perspective | Malaysian, Asian, and non-Asian hotel guests | 286 questionnaires | 4-5-star hotels in Klang Valley, Malaysia | As a whole, that the hotel guests’ perceptions of service quality provided by the hotel industry were lower than their expectations. The lowest expectations and perceptions were given by Malaysian hotel guests towards the hotels in Malaysia. | Further studies on service quality and satisfaction measurement can focus on the issue of the different sociodemographic variables on the impact on service quality dimensions and overall satisfaction levels, for instance, gender, age, level of education, profession, and other relevant economic factors. |

| Emphasis Difference | The importance of hotel employee service attitude and the satisfaction of internationaltourists | Kuo (2007) | To uncover the differences in the perceived importance of employee service attitude and in satisfaction with the service among customers from America, Japan, and Taiwan and to find critical elements of hotel employee service attitudes affecting the satisfaction of tourists of each nationality | Taiwanese, Japanese, and American tourists | 776 questionnaires | International tourist hotels in Taiwan | American travelers emphasize elements such as employees being able to solve their problems, and so are dissatisfied with the service when employees lack an adequate command of English. Taiwanese customers stress the importance of employees treating customers politely regardless of their attire. They feel that they are treated unfairly because of employee expectations of tips from well-dressed customers. | N/A |

| Complaining Behavior | National character and response to unsatisfactory hotel service | Huang et al. (1996) | To investigate the relationship between national character and specific guest responses to unsatisfactory hotel service | Japanese and American guests | 148 questionnaires | High-priced international tourist hotels in Taiwan | American respondents were more likely to stop patronizing the hotel, complain to hotel management, and warn family or friends than Japanese respondents were. Japanese respondents were more likely to take no action in response to unsatisfactory service. | To understand which dimensions of cultural values are more relevant to consumer complaining behavior, data from more countries are needed. |

| Complaining Behavior | Consumer complaint behavior of Asians and non-Asians about hotel services | Ngai et al. (2007) | To test the differences in the consumer complaint behavior of Asian and non-Asian hotel guests in terms of culture dimensions | Asians and Non-Asian tourists | 271 questionnaires | Hong Kong international airport, guests had previously stayed in hotels in Hong Kong | Asian guests are less likely to complain to the hotel for fear of “losing face” and are less familiar with the channels for complaint than non-Asian guests. They are more likely than non-Asian guests to take private complaint action, such as making negative word-of-mouth comments. | Future research should attempt to collect data from more visitors of different countries and increase the sample size of each country. |

| Complaining Behavior | Cross-national analysis of hotel customers’ attitudes toward complaining and their complaining behaviors | Yuksel et al. (2006) | Employing the concept of nationality to explain similarities and differences in complaining attitudes and behaviors of tourists | Turkish, Dutch, British, and Israeli tourists | 420 questionnaires | Tourists staying at hotels, Turkey | There are more differences than similarities in complaining behaviors of hotel customers from these countries. | Consumer complaining behavior field would benefit from further empirical cross-national research. |

References

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Law, R. The influence of online reviews to online hotel booking intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1343–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-García, M.; Muñoz-Gallego, P.A.; González-Benito, Ó. Tourists’ willingness to pay for an accommodation: The effect of eWOM and internal reference price. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 62, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, B.A.; So, K.K.F.; Bradley, G.L. Responding to negative online reviews: The effects of hotel responses on customer inferences of trust and concern. Tourism Manag. 2016, 53, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-L.; Chou, H.-L. Opinion mining from online hotel reviews—A text summarization approach. Inf. Process. Manag. 2017, 53, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R. What makes online reviews helpful? A diagnosticity-adoption framework to explain informational and normative influences in e-WOM. J. Business Res. 2015, 68, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilan, D.; Avello, M.; Martinez-Navarro, G. The influence of online ratings and reviews on hotel booking consideration. Tourism Manag. 2018, 66, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalo, L.V.; Flavian, C.; Guinaliu, M.; Ekinci, Y. Do online hotel rating schemes influence booking behaviors? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 49, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarzadeh, F.; Blum, S.C.; Adams, C. The impact of positive and negative e-comments on business travelers’ intention to purchase a hotel room. J. Hosp. Tourism Technol. 2015, 6, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, A.G.; Minazzi, R. Web reviews influence on expectations and purchasing intentions of hotel potential customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M.; Ekinci, Y. Avoiding the dark side of positive online consumer reviews: Enhancing reviews’ usefulness for high risk-averse travelers. J. Business Res. 2015, 68, 1829–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.E.K.; Lee, C.H. How do consumers process online hotel reviews?: The effects of eWOM consensus and sequence. J. Hosp. Tourism Technol. 2015, 6, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R. What makes an online consumer review trustworthy? Ann. Tourism Res. 2016, 58, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y. The power of expert identity: How website-recognized expert reviews influence travelers’ online rating behavior. Tourism Manag. 2016, 55, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-H.; Huang, C.-T.; Wu, S. National character and response to unsatisfactory hotel service. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1996, 15, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Royo Vela, M.; Tyler, K. Cultural perspectives: Chinese perceptions of UK hotel service quality. Int. J. Culture Tourism Hosp. Res. 2008, 2, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringam, B.B.; Gerdes, J., Jr. An analysis of word-of-mouse ratings and guest comments of online hotel distribution sites. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 2010, 19, 773–796. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. 1980 Culture” s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, C. Service Recovery Strategies: The impact of cultural differences. J. Hosp. Tourism Res. 2000, 24, 526–538. [Google Scholar]

- Barreda, A.; Bilgihan, A. An analysis of user-generated content for hotel experiences. J. Hosp. Tourism Technol. 2013, 4, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, Y. The antecedents of customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction toward various types of hotels: A text mining approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, N.; Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Online Complaining Behavior in Mainland China Hotels: The Perception of Chinese and Non-Chinese Customers. Int. J. Hosp. Tourism Adm. 2014, 15, 248–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ayeh, J.K.; Au, N.; Law, R. Investigating cross-national heterogeneity in the adoption of online hotel reviews. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckert, M.; Liu, X.; Law, R. A segmentation of online reviews by language groups: How English and non-English speakers rate hotels differently. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 48, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, A.T.; Tsai, C.W. Does national culture really matter? Hotel service perceptions by Taiwan and American tourists. Int. J. Culture Tourism Hosp. Res. 2009, 3, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, A.S. The Impact of Culture and Gender on Customer Evaluations of Service Encounters. J. Hosp. Tourism Res. 2000, 24, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Mattila, A.S.; Choi, S. A cross-cultural comparison of perceived fairness and satisfaction in the context of hotel room pricing. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mey, L.P.; Akbar, A.K.; Fie, D.Y.G. Measuring Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction of the Hotels in Malaysia: Malaysian, Asian and Non-Asian Hotel Guests. J. Hosp. Tourism Manag. 2006, 13, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, C.; Armstrong, R.W. Expectations for hotel service quality: Do they differ from culture to culture? J. Vacat. Mark. 1998, 4, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-M. The Importance of Hotel Employee Service Attitude and the Satisfaction of International Tourists. Service Ind. J. 2007, 27, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]