Sustainability of Live Video Streamer’s Strategies: Live Streaming Video Platform and Audience’s Social Capital in South Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

3. Method

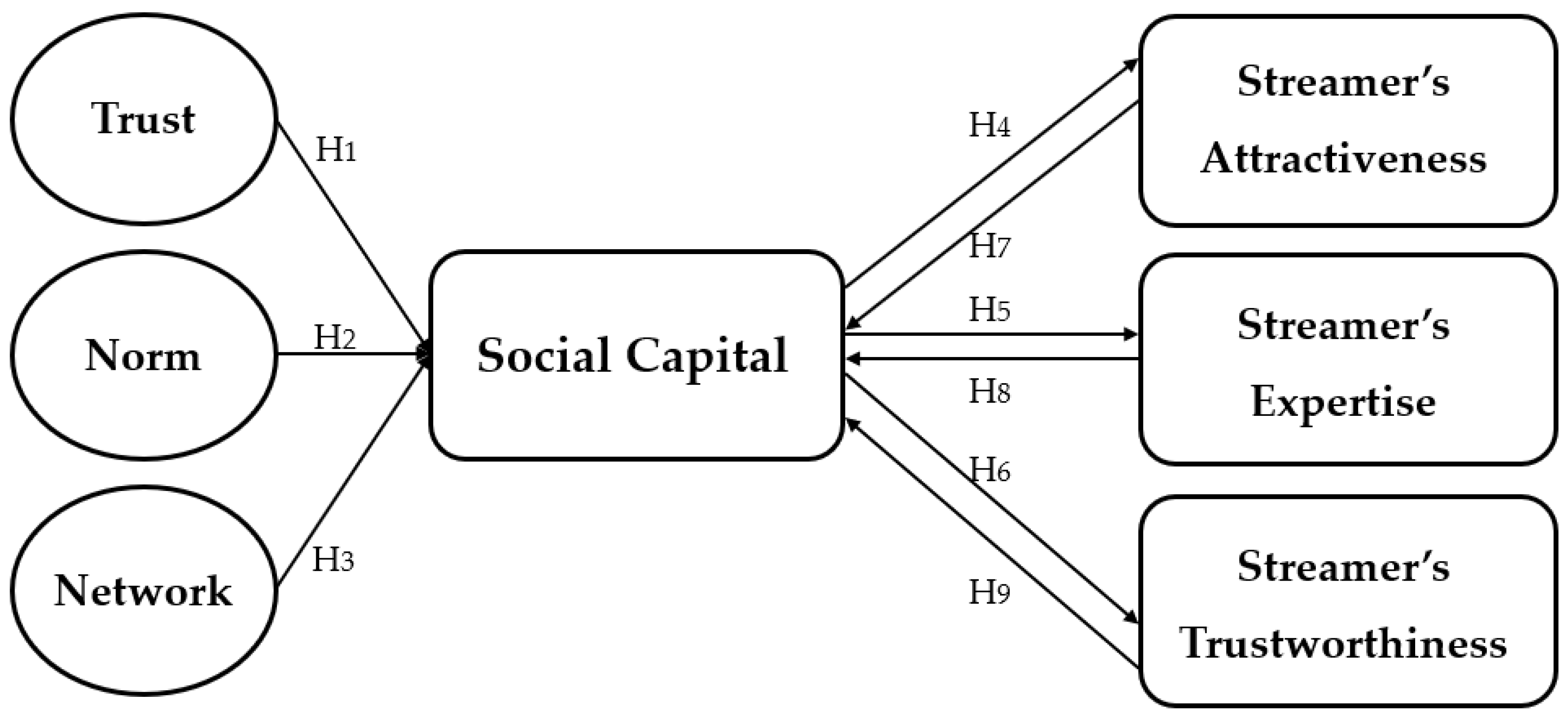

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Structural Equation Modelling

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Measurement Design

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion, Limitation, and Future Work

5.1. Discussion and Conclusion

5.2. Limitation and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamidi, F.; Shams Gharneh, N.; Khajeheian, D. A Conceptual Framework for Value Co-Creation in Service Enterprises (Case of Tourism Agencies). Sustainability 2020, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pencarelli, T.; Ali Taha, V.; Škerháková, V.; Valentiny, T.; Fedorko, R. Luxury Products and Sustainability Issues from the Perspective of Young Italian Consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thorburn, E.D. Social media, subjectivity, and surveillance: Moving on from occupy, the rise of live streaming video. Commun. Crit. Cult. Stud. 2014, 11, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research View Research. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/video-streaming-market (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Myeong, S.; Seo, H. Which type of social capital matters for building trust in government? Looking for a new type of social capital in the governance era. Sustainability 2016, 8, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, G.; Li, L.; Ma, G. Entrepreneurial Business Tie and Product Innovation: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, J.-D.; Huang, J.-S.; Su, S. The effects of trust on consumers’ continuous purchase intentions in C2C social commerce: A trust transfer perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Veerse, F. Mobile commerce report. Durlacher Res. Ltd. 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakh-Pines, A. Romantic Jealousy: Understanding and Conquering the Shadow of Love; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Cognition and motivation in emotion. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledgianowski, D.; Kulviwat, S. Using social network sites: The effects of playfulness, critical mass and trust in a hedonic context. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2009, 49, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Patino, A.; Pitta, D.A.; Quinones, R. Social media’s emerging importance in market research. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Putnam, R. The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. Am. Prospect. 1993, 13, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, E.M. Producing and consuming trust. Political Sci. Q. 2000, 115, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isham, J.; Kelly, T.; Ramaswamy, S. Social Capital and Economic Development: Well-Being in Developing Countries; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, M.F. Bringing Parent and Community Engagement Back into the Education Reform Spotlight: A Comparative Case Study. Doctral Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M. Social capital: The state of the notion. Soc. Cap. Glob. Local Perspect. 2000, 15–40. Available online: https://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/148625/j29.pdf?sequence=1#page=17 (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Wade, R.H. Making the world development report 2000: Attacking poverty. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1435–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Stone, W. Families, Social Capital & Citizenship Project. Australian Institute of Family Studies 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rus, A.; Iglič, H. Trust, governance and performance: The role of institutional and interpersonal trust in SME development. Int. Sociol. 2005, 20, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semerciöz, F.; Hassan, M.; Aldemir, Z. An empirical study on the role of interpersonal and institutional trust in organizational innovativeness. Int. Bus. Res. 2011, 4, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oláh, J.; Bai, A.; Karmazin, G.; Balogh, P.; Popp, J. The role played by trust and its effect on the competiveness of logistics service providers in Hungary. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oláh, J.; Karmazin, G.; Fekete, M.F.; Popp, J. An examination of trust as a strategical factor of success in logistical firms. Bus. Theory Pract. 2017, 18, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.A.A. The impact of source credibility on Saudi consumer’s attitude toward print advertisement: The moderating role of brand familiarity. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2011, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion. 1953. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, W.J. Attitudes and attitude change. Handb. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 44, 233–346. [Google Scholar]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange; Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 416–436. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, H.T.; Sheldon, K.M.; Gable, S.L.; Roscoe, J.; Ryan, R.M. Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. In Relationships, Well-Being and Behaviour; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 317–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.-H. Need for relatedness: A self-determination approach to examining attachment styles, Facebook use, and psychological well-being. Asian J. Commun. 2016, 26, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. A thematic coding system for the intimacy motive. J. Res. Personal. 1980, 14, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Weiss, W. The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 1951, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javalgi, R.G.; Traylor, M.B.; Gross, A.C.; Lampman, E. Awareness of sponsorship and corporate image: An empirical investigation. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSteno, D.; Valdesolo, P.; Bartlett, M.Y. Jealousy and the threatened self: Getting to the heart of the green-eyed monster. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Bridging the Research Traditions of Task/Ego Involvement and Intrinsic/Extrinsic Motivation: Comment on Butler (1987). J. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 81, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Rothman, A.J. Envy and Jealousy: Self and Society; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.J.; Churchill Jr, G.A. The impact of physically attractive models on advertising evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, M.L. Optimal Search for the Best Alternative. Econometrica 1979, 47, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaiken, S. Communicator physical attractiveness and persuasion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, L.R.; Homer, P.M. Physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser: A social adaptation perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 11, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Aronson, E. Opinion change as a function of the communicator’s attractiveness and desire to influence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 1, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.S. Mass Communication Theories and Research; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken, G. Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner Velázquez, B.; Fuentes Blasco, M. Why do restaurant customers engage in negative word-of-mouth? Esic Mark. Econ. Bus. J. 2012, 43, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Nix, G. Expressing intrinsic motivation through acts of exploration and facial displays of interest. Motiv. Emot. 1997, 21, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Jin, J. Is the web marketing mix sustainable in China? The mediation effect of dynamic trust. Sustainability 2015, 7, 13610–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, C.B.; Patel, V.K.; Wanzenried, G. A comparative study of CB-SEM and PLS-SEM for theory development in family firm research. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Heppner, P.P.; Mallinckrodt, B. Perceived coping as a mediator between attachment and psychological distress: A structural equation modeling approach. J. Couns. Psychol. 2003, 50, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcoulides, G.A. Modern Methods for Business Research; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F.K.; Barlow, E.A.; King, J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/02/05/smartphone-ownership-is-growing-rapidly-around-the-world-but-not-always-equally/ (accessed on 27 February 2019).

- Korean Communication Commission. 2018 Broadcasting Media Usage Survey; Korean Communication Commission: Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. In Social Structure and Network Analysis; Marsden, P.V., Lin, N., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, W. Measuring social capital; Australian Institute of Family Studies: Mellbourne, Australia, 2001; Volume 24, pp. 8–34.

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; SAGE Publications Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | Obs. (Proportion) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 112 (56%) |

| Female | 89 (44%) | |

| Age | 10–19 | 32 (16%) |

| 20–29 | 89 (44%) | |

| 30–39 | 72 (36%) | |

| 40–49 | 8 (4%) | |

| 50 or above | 0 (0%) | |

| Usage time | 0–1 hour | 10 (5%) |

| 1–2 hours | 52 (26%) | |

| 2–3 hours | 68 (34%) | |

| 3–4 hours | 51 (25%) | |

| 4–5 hours | 14 (7%) | |

| 5–6 hours | 5 (3%) |

| Items | Estimate | Cronbach’s α | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | 0.891 | 0.734 | 0.892 | |

| I trust the relationship among live streaming video audiences. | 0.840 | |||

| I believe the relationship among live streaming video audiences. | 0.851 | |||

| I believe the relationship among live streaming video audiences is reliable. | 0.877 | |||

| Norm of reciprocity | 0.804 | 0.579 | 0.804 | |

| I want to help other audience members on live streaming video platforms. | 0.773 | |||

| I often get help from other audience members on live streaming video platforms. | 0.763 | |||

| I believe audience members help each other on live streaming video platforms. | 0.745 | |||

| Network | 0.873 | 0.579 | 0.804 | |

| I cooperate with other audience members on live streaming video platforms. | 0.821 | |||

| I actively participate in live video streaming broadcasts. | 0.86 | |||

| I frequently collaborate with other audience members on live streaming video platforms. | 0.822 | |||

| Social Capital | 0.896 | 0.721 | 0.886 | |

| Interacting with people at live streaming video broadcasts that I frequently watch makes me want to try new things. | 0.838 | |||

| Interacting with people at live streaming video broadcasts that I frequently watch makes me feel like a part of a larger community. | 0.885 | |||

| Interacting with people at live streaming video broadcasts that I frequently watch reminds me that everyone in the world is connected. | 0.862 | |||

| Streamer Attractiveness | 0.858 | 0.671 | 0.859 | |

| Attractive | 0.787 | |||

| Handsome/Beautiful | 0.808 | |||

| Sexy | 0.865 | |||

| Streamer Expertise | 0.956 | 0.880 | 0.957 | |

| Expert | 0.921 | |||

| Experienced | 0.967 | |||

| Qualified | 0.929 | |||

| Streamer Trustworthiness | 0.921 | 0.799 | 0.923 | |

| Honest | 0.882 | |||

| Trustworthy | 0.914 | |||

| Dependable | 0.887 | |||

| Variables | Correlation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Trust | 1 | ||||||

| Norm of reciprocity | 0.710 (0.504) | 1 | |||||

| Network | 0.831 (0.69) | 0.744 (0.554) | 1 | ||||

| Social Capital | 0.722 (0.521) | 0.588 (0.346) | 0.817 (0.667) | 1 | |||

| Attractiveness | 0.538 (0.289) | 0.548 (0.300) | 0.654 (0.428) | 0.756 (0.571) | 1 | ||

| Expertise | 0.585 (0.342) | 0.519 (0.269) | 0.62 (0.384) | 0.674 (0.454) | 0.716 (0.513) | 1 | |

| Trustworthiness | 0.761 (0.579) | 0.548 (0.548) | 0.746 (0.557) | 0.715 (0.511) | 0.569 (0.324) | 0.678 (0.472) | 1 |

| Fit Index | Ideal Value | Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | <3 | 1.607 | Acceptable fit |

| GFI | >0.9 (good fit) 0.8–0.89 (acceptable fit) | 0.894 | Acceptable fit |

| AGFI | >0.9 (good fit) 0.8–0.89 (acceptable fit) | 0.854 | Acceptable fit |

| CFI | >0.9 | 0.971 | Good fit |

| NFI | >0.9 | 0.928 | Good fit |

| RMSEA | ≤0.05 (close fit) 0.05–0.08 (fair fit) 0.08–0.10 (mediocre fit) | 0.055 | Fair fit |

| Standardized RMR | −1 < Standardized RMR < 1(good fit) | 0.0366 | Good fit |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust → Social capital | 0.497 | 0.193 | 2.523 | ** |

| Norm of reciprocity → Social capital | −0.126 | 0.183 | −0.901 | 0.368 |

| Network → Social capital | 0.996 | 0.34 | 3.473 | *** |

| Social capital → Attractiveness | 0.797 | 0.08 | 9.396 | *** |

| Social capital → Expertise | 0.677 | 0.084 | 9.474 | *** |

| Social capital → Trustworthiness | 0.971 | 0.093 | 10.789 | *** |

| Attractiveness → Social capital | −0.748 | 0.264 | −2.752 | ** |

| Expertise → Social capital | 0.192 | 0.09 | 1.807 | * |

| Trustworthiness → Social capital | −0.054 | 0.173 | −0.331 | 0.741 |

| Hypothesis | Content | Verification |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Trust → Social capital | Supported |

| H2 | Norm of reciprocity → Social capital | Rejected |

| H3 | Network → Social capital | Supported |

| H4 | Social capital → Attractiveness | Supported |

| H5 | Social capital → Expertise | Supported |

| H6 | Social capital → Trustworthiness | Supported |

| H7 | Attractiveness → Social capital | Supported |

| H8 | Expertise → Social capital | Supported |

| H9 | Trustworthiness → Social capital | Rejected |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heo, J.; Kim, Y.; Yan, J. Sustainability of Live Video Streamer’s Strategies: Live Streaming Video Platform and Audience’s Social Capital in South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051969

Heo J, Kim Y, Yan J. Sustainability of Live Video Streamer’s Strategies: Live Streaming Video Platform and Audience’s Social Capital in South Korea. Sustainability. 2020; 12(5):1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051969

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeo, Jeakang, Yongjune Kim, and Jinzhe Yan. 2020. "Sustainability of Live Video Streamer’s Strategies: Live Streaming Video Platform and Audience’s Social Capital in South Korea" Sustainability 12, no. 5: 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051969

APA StyleHeo, J., Kim, Y., & Yan, J. (2020). Sustainability of Live Video Streamer’s Strategies: Live Streaming Video Platform and Audience’s Social Capital in South Korea. Sustainability, 12(5), 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051969