1. Introduction

In the field of education, the use of terms such as “environmental” or “sustainability” has evolved since their beginning. The concepts are changing, as are the practices and learning processes, as well as society and its individual and collective agents. Some argue that the concept determines what has been learned in practice; others consider action, rather than concepts, to be more important. For many [

1,

2] “the emergence of the discourse of education for sustainable development (ESD) over the past 15 or so years is viewed as a progressive transition in the field, along similar lines to the positive portrayal of prior historical transitions from nature study to conservation education, to environmental education” [

3].

The United Nations Agenda 2030 proposes a new integrative path towards sustainability, where Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) visualize a future of inclusive equity, justice, and prosperity and take into account social, environmental, and economic wealth. The Agenda 2030 emphasizes education, that is, it acknowledges education as a means to achieve all of the SDGs. In this context, the Incheon Declaration [

4] was approved at the World Education Forum in 2015, emphasizing the significant role of education as a main driver to fulfill the SDGs. However, the complexity of sustainability as a concept makes it difficult to relate the SDGs to educational outcomes and to education for sustainable development (ESD) [

5]. Sustainability, as an educational task, has not been accurately defined, and is often considered too vague and abstract [

5]. Thus, ESD has been interpreted in different ways around the world and often differs according to context and culture [

6].

In the field of academia, with international summits, education is deemed necessary in light of environmental problems. Therefore, Schoenfeld [

7] concisely emphasized that “it is a cadre of scientific leaders that sets the environmental agenda in this country [USA]". In other places, scientists like Carson [

8], Ehrlich [

9], Goldsmith et al. [

10], and Hardin [

11], who placed education on the environmental agenda, supported that idea as well [

12]. Environmental and sustainability education is still currently a topic of theoretical and practical discussion, showing different perspectives and inconsistencies [

1,

10,

13].

Divergences of perspectives can be particularly noticeable among those that defend the position that the purpose of environmental education (EE) should be specifically to talk about nature, and those that support the idea that the concept of sustainability should be incorporated in education, going beyond nature and incorporating a holistic point of view, incorporating also social dimensions. Others have stated that education for sustainable development (ESD) is shifting in the same manner as the goals of the EE [

14], or that the change in terminology goes beyond this [

15]. It is necessary to create a common vision of the field of education and of the direction of sustainability, guided by SDGs in order to help educators to define the required skills and methodologies to be taught. Given that the environmental crisis is, in part, a global issue, should educational approaches be much broader? Alternatively, do we need to define sustainability and make it concrete, with a local view, in order for it to succeed? Is it maybe just a matter of thinking about ethical values globally? Or does it matter what we call it? What direction do we want to take going forward within the field of education for a sustainable future? As mentioned by Monroe [

14], it may be time to borrow from the success of overlapping and intertwined concepts and work on the type of education that meets the current needs of citizens and communities; ”we need quality education that prepares people to understand multiple views; to listen and communicate with others; to vision and evaluate options; to collect, synthesise and understand data; to learn how others have balanced contentious elements of an issue; and to be able to adopt actions [

14]”.

The aim of this paper is to analyze conceptual discussion of environmental and sustainability education and propose an approach within an educational framework by which to integrate concepts and visions under the umbrella of SDGs, guided by a previous review of emerging concepts such as learning for sustainability and sustainable education. The research question is therefore: what direction should the notion of an integrated sustainable future take within an educational framework? The hypotheses that guides this paper is: “The need to conceptualize sustainability into Education in an integrated way, can be gathered by existing concepts such as sustainable education and learning for sustainability, leading us to a deeper conception of an education based on values”.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to meet the main objectives of this work, the methodology was structured around different steps. Firstly, we identify the need to examine the creation and evolution of the environmental education and education for sustainable development concepts, in order to establish a background to the development of our approach. We consider the works of McKeown and Hopkins (2003) [

1] and Sterling (2004) [

16] as references in this subject. In addition, chronological international milestones in the context of the United Nations guide us from the 1960s to the Earth summit in the 1990s.

Secondly, to answer the research question regarding which direction we should take in the field of education within the framework of the international Agenda 2030, learning for sustainability [

17] and sustainable education [

16,

18,

19] approaches are taken as references. These were considered after conducting a bibliographic search in the largest academic database, the Web of Science, in the period 2000–2019. This search was undertaken using the keywords "environmental education", "education for sustainable development", "education for sustainability”, “learning for sustainability”, and “sustainable education”. The last two concepts yielded the smallest number of publications; however, they are emerging concepts for the era of the 2030 Agenda, due to their comprehensive vision, and for this reason, were taken as references. In order to test the hypothesis, a content analysis of the main publications regarding these concepts was carried out. Moreover, other concepts derived from these will also be taken into consideration in the analysis and study.

3. Background: The Paradigm of Environmental and Sustainable Development Education

In the academic and research field, the Journal of Environmental Education was the first specialized journal on the topic. In an article from 1969, Stapp et al. [

20] proposed the following definition for the term "environmental education":

“Environmental education is aimed at producing a citizenry that is knowledgeable concerning the biophysical environment and its associated problems, aware of how to help solve these problems, and motivated to work toward their solution”.

(p. 34)

This definition from Stapp served as a precursor for those that were subsequently proposed, such as that of the International Unit for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [

21]. Stapp argued that this approach to education was different from the one offered by the conservation approach, because the latter was aimed at natural resources and not so much at the community’s environment and its associated problems. The latter idea was emphasized by the sentence “the role of the citizen in working, both individual and collectively, toward the solution of problems that affect our wellbeing” [

20] (p. 34). Likewise, this definition does not only refer to knowledge, but also to the change in mentality that would result in action. Therefore, it is not surprising that environmental education is mostly introduced in natural science subjects, since the terminology used, such as “biophysical” or even “environment”, is usually only related to this field. Nonetheless, already back then, this definition was close to what is promoted today, from knowledge to action; motivation and involvement of citizenship.

Annette Gough [

22], in her reflection on the history of terminology and research in Environmental Education, points out that we must take into account that they are definitions made from a Western and masculine perspective. In the definitions adopted at the Belgrade Conference, “man” or “he” were used, but in 1975 when reconstructing them, some concepts were edited. For example, “man-made” was rewritten as “built”. The latter might be related to the fact that the guidelines were drafted during the International Year of Women, and that the United Nations advocated non-sexist writing, which has been taking effect. However, "man" was still used in the documents at the Tbilisi conference [

23]. It is vital to take into account those considerations in order to capture a full spectrum of the history and evolution of the proposed concept. Moreover, the debate on the paradigm of environmental education is identified with Mrazek’s “Alternative Paradigms in Environmental Education Research” [

24]. This book is a key reference in the field, although it has also been criticized by some scholars, such as Louise Chawla [

25]. Chawla underlines the incorrect use of the term "paradigm" and the lack of presence of the media or other sources that could also be valuable to conduct environmental education research.

A turning point in the evolution of the concept is the Brundtland Report (1987) [

26] and the Earth Summit in Rio (1992) [

27]. Through the admission and use of the expression "Sustainable Development", a new paradigm was accentuated in relation to education, that is, a changing terminology was generated when education for sustainable development (ESD) began to be introduced. Despite its multitude of interpretations, the defenders of the concepts of education for sustainable development and education for sustainability alleged that the concept of sustainability implies a more holistic and comprehensive ideology in the way of approaching the subject, i.e., covering the three dimensions of sustainability that would include the environment, society, and the economy. Sterling [

16] argued that from his perspective, EE is part of ESD, which can be understood as one of the three pillars to work on. On the other hand, McKeown and Hopkins [

1] argued that, from their point of view, while EE and ESD have similarities, they also pointed out their differences in order to emphasize the importance of each discipline individually: “EE and ESD are different, but complementary. It is important that the EE and the ESD maintain separate agendas, priorities, and programmatic development. The two conceptualizations will influence each other, and each will benefit from the independent growth of the other” [

1]. Looking at and analyzing international documents, the approaches of both Belgrade and Tbilisi were less directed at people (i.e., human rights, democracy, or standard of living) and focused more on the difficult context of the environment. Furthermore, the critical situation of the population was addressed in the 1980s and 1990s with the preparation of the Earth Summit, the Agenda 21 Program, and a series of relevant United Nations conferences [

1].

In the decade of the 1990s, after the Earth Summit in Rio (1992) and using the definition of sustainable development of Brundtland, the concept of education for sustainable development (ESD) began to be incorporated. UNESCO, as an international organization that aims to set a trend at the international level, began to use the term ESD, which is also currently included in the context of the 2030 agenda with the Sustainable Development Goals [

28]. Thus, in international policy statements, the most used variant is that of "sustainable development" and therefore ESD, defined by UNESCO [

29].

It is clear that this concept, sustainable development, wants to encompass a holistic ideology, integrating sustainability as a term. However, the debate is generated by the term "development"; that is, what does “development” or “sustainable development” mean and what does it involve? At the academic level, one of the main economic issues that has created discussion is the concept of sustainable development. This concept is conditioned by the paradigm of the orthodox economy that equates economic growth with increased welfare and full employment, which determines the need for and goodness of sustained growth [

30]. However, that model of economic growth which has been maintained so far is precisely the one that has led us to the current environmental and social crisis. It is this economic model that undermines the ecosystem of which we are a part, as well as our future, which is why the concept itself is considered to be an oxymoron [

30]: planetary boundaries exist, and that development based on consumption and that identifies growth thinking of natural resources as something unlimited, contradict each other. Thus, despite the terminological contradiction, is it really a more complete concept compared to “environmental education”? Education and sustainability are both complex concepts with a complex relationship, so we use the literature and emerging concepts to guide this study and answer the defined research questions.

5. Discussion

Different paradigms respond to their respective historical contexts. Concepts evolve and change, as do the priorities and needs of each moment. Taking into account the current socio-environmental crisis, an in the era of de Agenda 2030, it is necessary to address the problem from a holistic view. Therefore, we choose and justify the learning for sustainability (LfS) focus. However, in the various local contexts of educational practice, that is, in schools, the most used and familiar concept may not always be the one that is more holistic or ideal. Nonetheless, it is considered necessary to start moving from environmental education to education for sustainability in order to generate changes in mentalities and integrate the concept of sustainability [

48], understanding it holistically and comprehensively for action without being exclusive of one over the other.

Conceptualization is important, since words contribute to the explanation of social realities, interactions with the environment, and the generation of new concepts in practice; “science deals directly with concepts and not with ‘realities ’, because the integrating units of scientific discourse are concepts and not directly with reality or phenomena. The concepts are, in turn, mental constructions, are constructs, abstractions extracted from objects and concrete real events” [

49].

In the framework of education, the use of sustainability concept, which has integral and holistic implications (unlike what is associated with the word ’environmental’), can generate changes through its use in the mentality of how to address the problem and the socio-environmental crisis. Currently, the term ‘sustainability’ may be often used without linking it to the social dimension, for example by only associating it with environmental sustainability. However, that does not mean that this knowledge cannot also be integrated, and by incorporating the word into the discourse, it can facilitate the transition to the changes in mentality that are sought.

In terms of education for sustainability and its teaching in a holistic and integral way, certain methodologies help to generate spaces where the subject of sustainability traverses and works through different fields of knowledge. For example, methodologies such as Outdoor Learning, experiential learning, teaching by projects, and active pedagogies are giving rise to a more integrative educational program. At the institutional level, the concept itself can have a lot of power, or it should have, but it cannot be placed at the same level of a government that is responsible for the conservation of a forest or for the integral and holistic (sustainable) management of a protected area. For example, the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve (UNESCO MAB) program was created by the holistic need to manage spaces (the broken-thread argument). In this case, it was seen that the conservation of untouchable natural spaces does not always make sense if there are people living in that space. The ecosystem can live with the human if it is done in a sustainable way. Therefore, conceptually the program evolved from dealing with conservation, then to sustainability, and then to sustainable management. A similar process can be seen in the transition from environmental education to education for sustainability.

However, using one concept over another does not mean that it has more or less value. In spite of our reasons for choosing a particular concept, in certain practical contexts (where, for example, one concept is better understood than another) we understand that it may be more useful to treat the terms as synonyms and equivalents in their intentions. Javier Benayas [

50] uses a metaphor that we consider to be very helpful to deal with the issue: “The important thing is not the color of the flag with which it is fought, but to stay together to fight a powerful enemy under a common cause” [

47]. Thus, the important points are the actions that are generated and carried out, but without losing sight of the concepts and terms that we use, and what effects they have on us, i.e., what they mean in our way of thinking and seeing the world. It is through these terms that we create one reality or another; we are continuously creating realities, and we live based on them and the beliefs embedded in them.

6. Conclusions

This analysis concludes with a proposal for further theoretical research regarding education and sustainability, where it is a debate on which concept should be used. Thereby, we conclude that a new integrative approach inspired by the Education based on Values concept, and integrating other concepts, will help to better conceptualize sustainability into Education, as explained in the proposed model (

Figure 3). Thus, the idea of the hypothesis that guides this study is confirmed.

The debate will consist of evaluating what values we want for our society; in this context, sustainability should be one of the key concepts, that taking as a reference the SDG umbrella, it has a lot of ethical/moral values inside it. Likewise, the knowledge to be generated exists ‘outside’ but also ‘inside’ by means of the preconceptions of each person. Current society is complex and trans-disciplinary challenges require a new way of producing knowledge within applied frameworks. For instance, values such as respect—respect for mother nature, for persons no matter the place of birth or religion, solidarity, empathy with persons around the world—can help us to understand that the world is one, so that global citizenship can be developed based on that value. Sterling [

51] proposes that by applying critical thinking skills (including normative and values analyses and systems thinking) the learner’s worldview, values, and personal ways of knowing are challenged and changed accordingly. This authors promotes this deeper, transformative learning, in which a shift of consciousness can occur and permit greater awareness not only of what and how to change the world, but why [

31].

Based on the results, we generate the following proposal (

Figure 3) considering the need to be graphically represented some relevant and growing concepts from the literature that can be applied in practice. The concepts include the following:

EE: Environmental Education

ESD: Education for Sustainable Development

EfS: Education for Sustainability

SE: Sustainable Education

LfS: Learning for Sustainability

SD: Sustainable Development

OE: Outdoor Education

GCE: Global Citizenship Education

CJE: Climate Justice Education

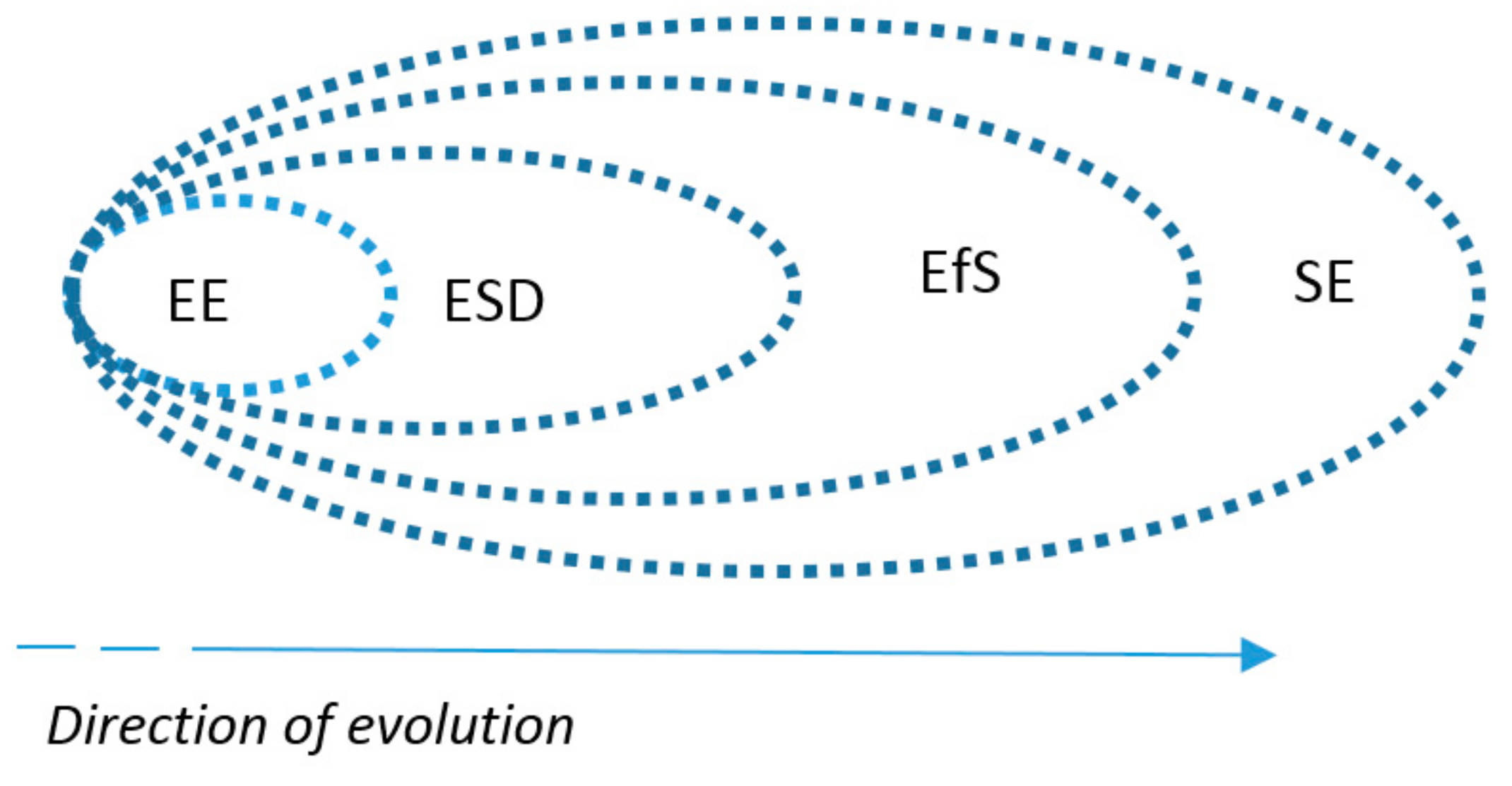

We share the ideas in Sterling’s diagram and additionally integrate some of the above-explained concepts. First, we highlight some key points:

practitioners and theorists are involved in a continuous process of reflexive (and often difficult) learning through which the views of the adequacy or totality of educational orientations are modified over time;

through this process, the previous conceptions in this area are not rejected but are subsumed within the later conceptions;

the validity of previous conceptions is not questioned, but their claims of sufficiency are challenged.

In the proposal (

Figure 3), the term learning for sustainability and what that implies is considered to be of great interest and to make important contributions, which enriches the conceptual review so far. LfS proposes to expand knowledge, promote a quality education, and achieve a paradigm shift through the concept of sustainable education. LfS refers to sustainability, without losing sight of its three pillars (environmental, social, and economic), and also encompasses concepts such as education for global citizenship (GCE) and outdoor education (OE). We want to pay special attention to outdoor education because of its potential and educational relevance, since it implies experiential learning with a greater impact on the student learning process [

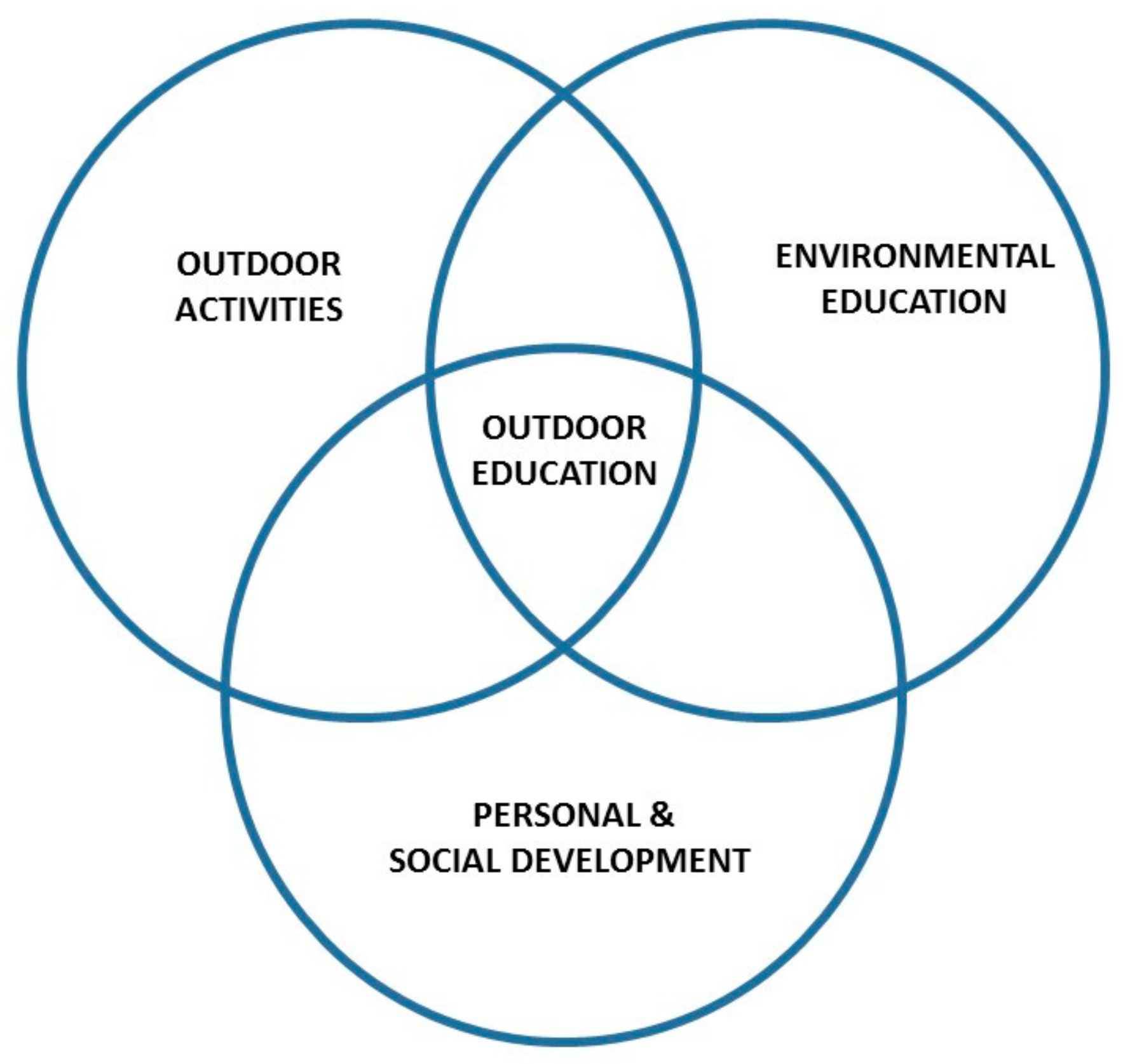

37].

Outdoor education has its origins in the debates among the philosophers of Ancient Greece about the dominance of the body or the mind to control the actions of the individual. The debate has progressed over the centuries with contributions from philosophers and scholars from many countries. In modern educational terms, the problem is whether a modern, mainly intellectual, form of education is suitable for the proper development of the individual or if there are more appropriate forms of direct educational experience that foster awareness of oneself, of others, and of the environment. In therapeutic terms, the problem is whether educational and outdoor adventure experiences can address some of the personal and social difficulties we encounter in current modern societies [

35]. One of the objectives that education can have in this field is to ’reconnect’ students with nature. In that sense, we consider the reflection made by authors Mcphie and Clarke [

52]; they point out that we cannot expect people to “reconnect” with nature since there is not an ideal state that corresponds to that, but we can expect people to consider nature as a material concept that can be experienced in the concept creation process. Likewise, education for climate justice [

43] includes nuances worth taking into account, such as addressing and harnessing the work of social movements and their role in education.

In this context, we understand that learning for sustainability (LfS) is in line with education for sustainability (EfS). Although the use of LfS is of interest, concept of EfS can be more popular in some cases. Therefore, the use of the term EfS will be more effective given its extensive familiarity depending on the context, generating a more efficient and comprehensive communication without losing sight of the contributions made by LfS. It is also worth noting the use of dotted circles in

Figure 3, highlighting Sterling’s key ideas mentioned above that invoke the need to understand these concepts as permeable to each other. In the proposed diagram (

Figure 3), reference is made to encompassing concepts within the framework of education based on values. These concepts are based on values to be transmitted to guide the way towards environmentally and socially sustainable societies. This is the main key element of the paper, as it is a concept that helps us understand what should be under sustainability and under what the Agenda 2030 is looking for. The proposed approach to education based on values leads debate and reflection for the academic field towards education and sustainable futures.

Finally, the limitation of this research is that is not a deep literature review, but an analysis of concepts chosen by the researcher by specific methodology. For future research, it would be interesting to continue analysing the concept of “education based on values” related to sustainability to better understand the values under consideration and how they might differ according to context, local meaning and use of the concepts.