French Media Representations towards Sustainability: Education and Information through Mythical-Religious References

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Method and Corpus

4. Findings

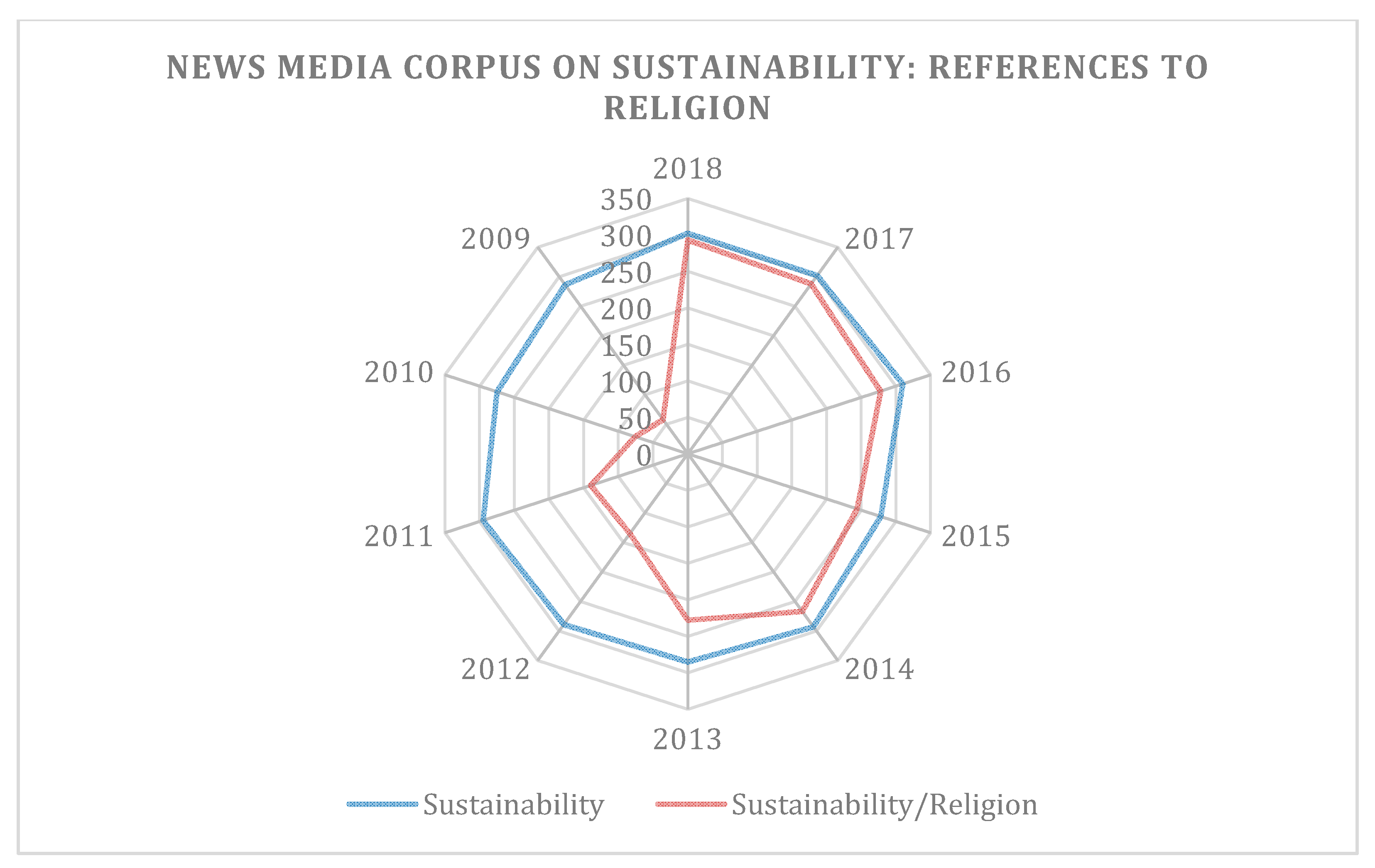

4.1. Evolution of Religious References in the Media Information Offer on Sustainability

4.2. Sustainability and Religion in French News Media: Sociocultural Representations

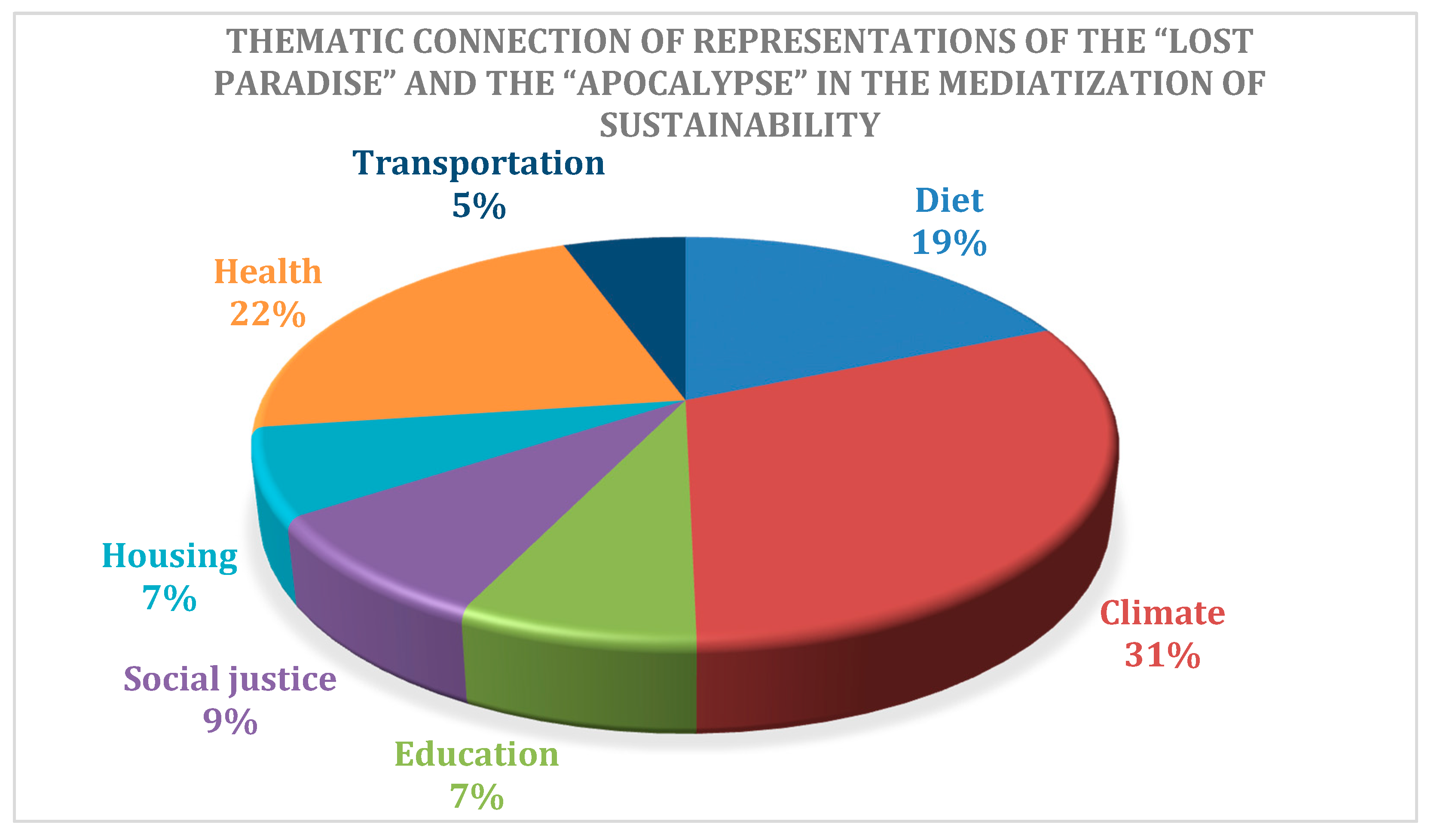

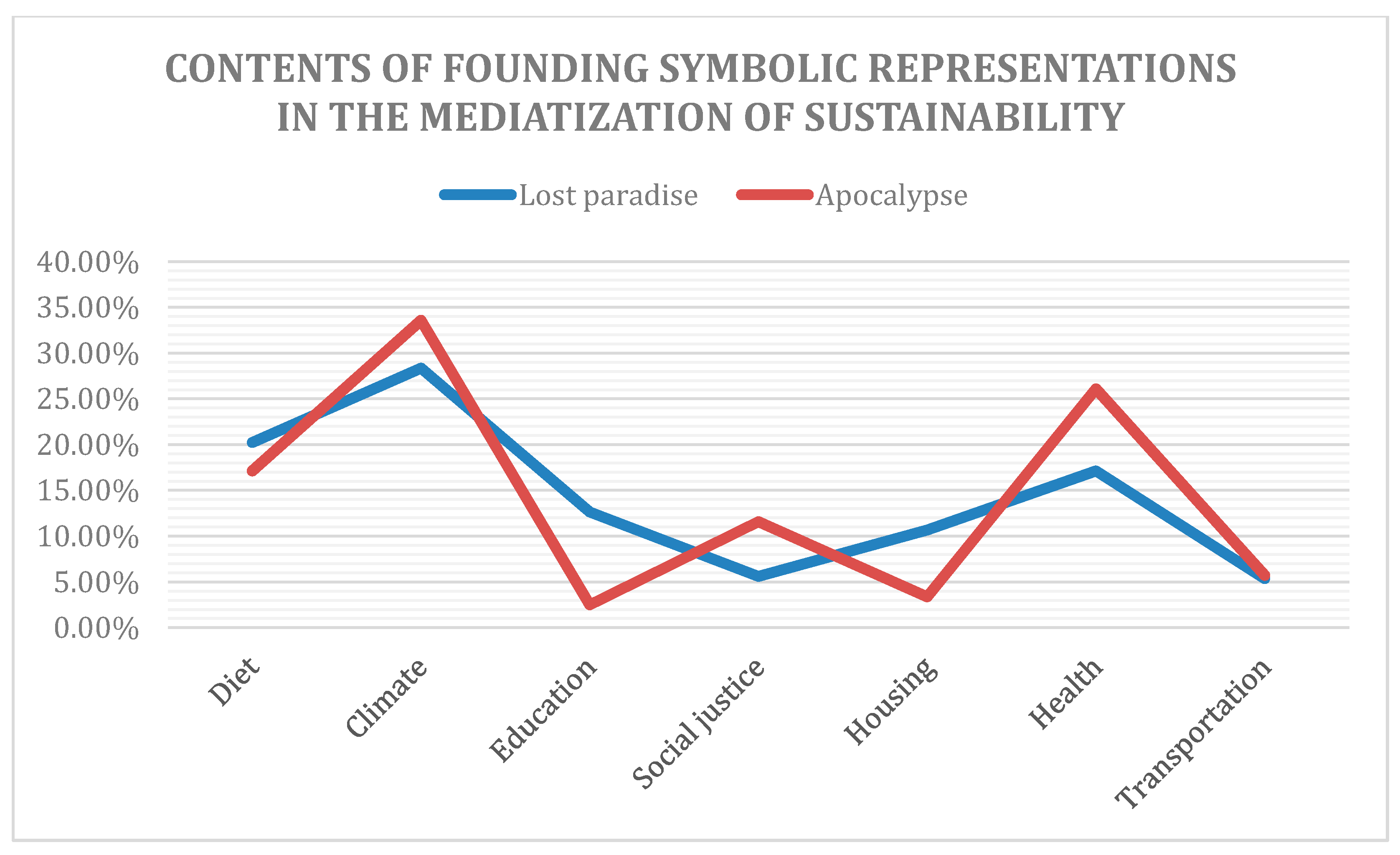

4.2.1. Founding Symbolic Representations: The Mediatization of Paradise and the Apocalypse

4.2.2. Dogmatic Representations: The Mediatization of Promises and Hope

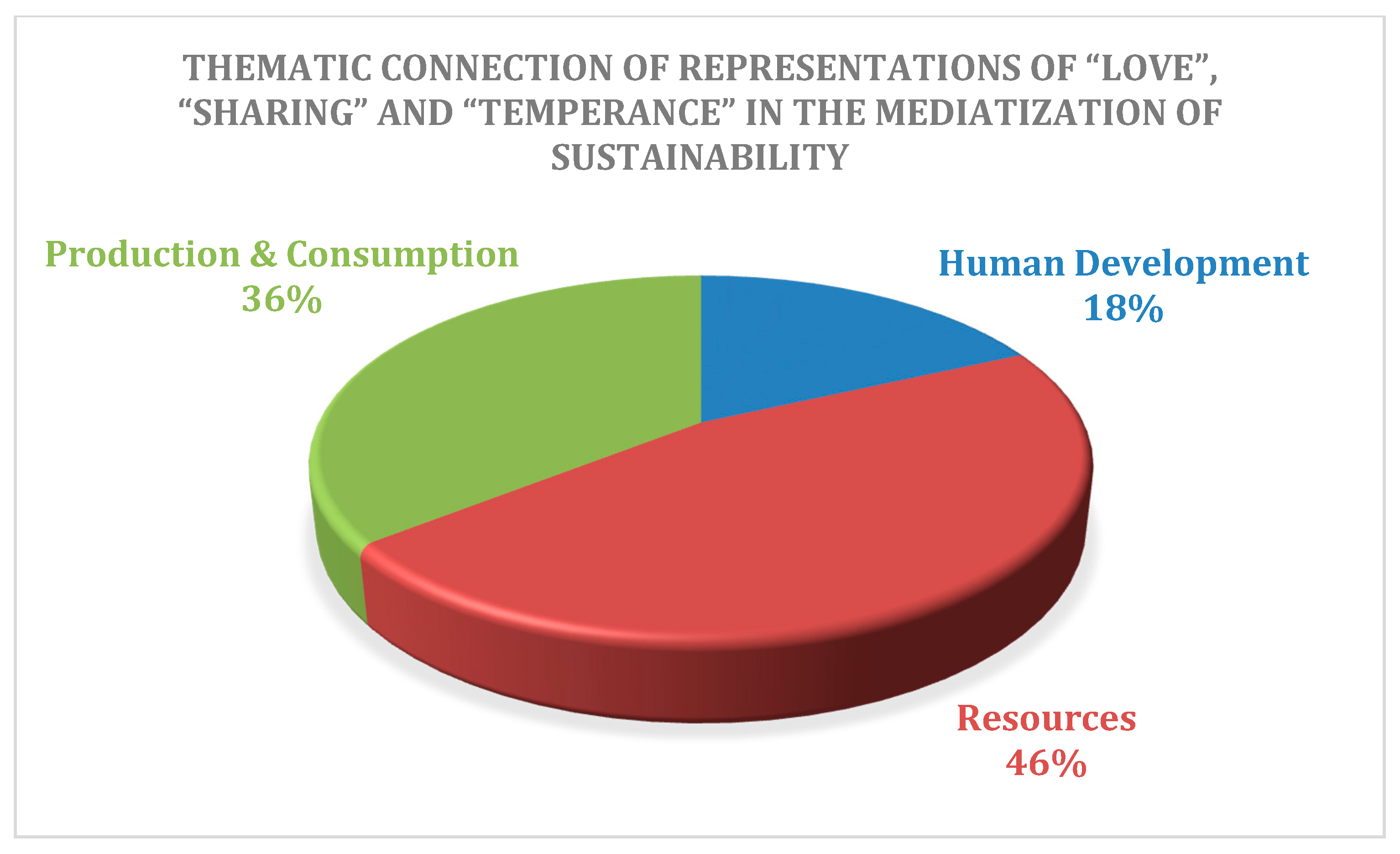

4.2.3. Pragmatic Representations: The Mediatization of Love, Sharing, and Temperance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cassirer, E. La Philosophie des formes symboliques. 2. La pensée mythique; Minuit: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bratosin, S. La concertation. Forme symbolique de l’action collective; L’Harmattan: Paris, Paris, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bratosin, S. La concertation. De la pratique au sens; Peter Lang: Berne, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bodt, J.-M. La “Cite Ecologique” Dans L’espace Public Médiatique: Trajectoires De Controverses Environnementales Dans La Presse Generaliste Française, These De Doctorat; Université Toulouse–Jean Jaurès: Toulouse, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Comby, J. Quand l’environnement devient médiatique: Conditions et effets de l’institutionnalisation d’une spécialité journalistique. Réseaux 2009, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendron, C.; Revéret, J.-P. Le développement durable. Écon. Soc. 2000, 37, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Godard, O. Le développement durable: Paysage intellectuel. Nat. Sci. Soc. 1994, 2, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, F. Greening Faith: Turning Belief into Action for the Earth. Zygon® 2011, 46, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D. Economics, equity and sustainable development. Futures 1988, 20, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuindeau, B. Développement Durable et Territoire; Presses Univ. Septentrion: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Archibugi, F.; Nijkamp, P. Economy and ecology: Towards sustainable development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B. The concept of sustainable economic development. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianoni, S.; Porcelli, M.; Tiezzi, E. Sustainable development models for the analysis of the Province of Modena (Italy). WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 1970, 34, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff, D.W.; Goldsmith, A.A. Promoting the sustainability of development institutions: A framework for strategy. World Dev. 1992, 20, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.R. Sustainability is not about money! The case of the Belize Chamber of Commerce and Industry’. Dev. Prac. 1997, 7, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, A.; Radcliffe, N. Sustainability: A Systems Approach; Earthscan: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.E. Toward some operational principles of sustainable development. Ecol. Econ. 1990, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; MacBeth, J.D. Risk, Return and Equilibrium: Empirical Tests. J. Political Econ. 1973, 81, 607–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune, J.; Hughes, J. Modern academic myths. In Systems for Sustainability: People, Organizations and Environments; Stowell, F.A., Ison, R.L., Armson, R., Holloway, J., Jackson, S., McRobb, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1997; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Frans, R. Sustainability of high-input cropping systems: The role of IPM. FAO Plant Protect. Bull. 1993, 41, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Fresco, L.O.; Kroonenberg, S.B. Time and spatial scales in ecological sustainability. Land Use Policy 1992, 9, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheel, M. The Liberation of Nature: A Circular Affair. Environ. Ethics 1985, 7, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lequeux, E. Exposition: Olafur Eliasson fait son numéro d’urgence climatique. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/culture/article/2019/08/16/exposition-olafur-eliasson-fait-son-numero-d-urgence-climatique54998893246.html (accessed on 18 August 2019).

- Passmore, J. Man’s Responsibility for Nature; Duckworth: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Pelt, M.J.F.v.; Kuyvenhoven, A.; Nijkamp, P. Project appraisal and sustainability: Methodological challenges. Proj. Apprais. 1990, 5, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rasmussen, L.L. Energy: The Challenges to and from Religion. Zygon® 2011, 46, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, M. Animal Rights: A Philosophical Defence; Macmillan: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, D. Anthropcentrism, Atomism and Environmental Ethics. In Ethics and the Environment; Scherer, D., Attig, T.H., Eds.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X. A Cultural Approach to Discourse; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, P. Animal Liberation: A New Ethic for our Treatment of Animals; Jonathan Cape: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Sterba, J. From Biocentric Individualism to Biocentric Pluralism. Environ. Ethics 1995, 17, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, K. The Power and Promise of Ecological Feminism. Environ. Etheric 1990, 12, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Experiences with Sustainability Indicators and Stakeholder Participation: A Case Study Relating to a Blue Plan Project. In Malta, International Sustainable Development Research; University of Manchester, ERP Environment: Manchester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bossel, H. Assessing viability and sustainability: A systems-based approach for deriving comprehensive indicator sets. Conserv. Ecol. 2001, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A. Criteria for sustainability in the development of indicators for sustainable development. Chemosphere 1996, 33, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hak, T.; Moldan, B.; Dahl, A.L. Sustainability Indicators: A Scientific Assessment; Island Press: Washington DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M. Issue-attention and punctuated equilibria models reconsidered: An empirical examination of the dynamics of agenda-setting in Canada. Can. J. Political Sci./Rev. Can. Sci. Polit. 1997, 30, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.B. The Media and Modernity. A Social Theory of the Media; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, R. Faking Nature: The Ethics of Environmental Restoration; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Glacken, C.J. Traces on the Rhodian Shore: Nature and Culture in Western Thought from Ancient Times to the End of the Eighteenth Century; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA; London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove, E.C. Foundations of Environmental Ethics; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, P. Evolutionary analogues and sustainability: Putting a human face on survival. Futures. 1996, 28, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, H. The Imperative of Responsibility. In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, L. Noah’s Ark Goes to Washington: A Profile of Evangelical Environmentalism. Soc. Comp. 1997, 44, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naisbitt, J. The Trend Report: A Quarterly Forecast and Evaluation of Business and Social Development; Center for Policy Process: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, V. Nature, Self and Gender: Feminism, Environmental Philosophy, and the Critique of Rationalism. Hypatia 1991, 6, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolston, H., III. Science and Religion in the Face of the Environmental Crisis. In The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology; The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology; Gottlieb, R.S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 376–397. [Google Scholar]

- Routley, R. Is There a Need for a New, an Environmental Ethics? In Proceedings of the Fifteenth World Congress of Philosophy; World Congress of Philosophy: Varna, Bulgaria, 1973; pp. 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, N. The concept of agricultural sustainability. Agric. Ecosys. Environ. 1993, 46, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schley, S.; Laur, J. The sustainability challenge: Ecological and economic development. Sys. Think. 1996, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stivers, R.L. The sustainable Society: Ethics and Economic Growth; Westminster Press: Louisville, KY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Stowell, F.A.; Ison, R.L.; Armson, R.; Holloway, J.; Jackson, S.; McRobb, S. (Eds.) Systems for Sustainability: People, Organizations and Environments; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P. Respect for Nature: A Theory of Environmental Ethics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Throop, W. Environmental Restoration: Ethics, Theory and Practice; Humanity Books: Amherst, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vivien, F.-D.; Dannequin, F.; Diemer, A.; Petit, R. La nature comme modèle? Écologie industrielle et développement durable. Ca. CERAS Nat. Cult. Econ. 2000, 38, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, J.; Tucker, M.E. Forum on Religion and Ecology at Yale. Available online: http://fore.yale.edu/about-us/ (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Christiansen, D. Church Teaching, Public Advocacy, and Environmental Action. Zygon® 2011, 46, 972–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clugston, R.; Holt, S. Exploring Synergies between Faith Values and Education for Sustainable Developmen; Earth Charter International: San José, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, R. You gonna be here long? Religion and Sustainability. World. Glob. Rel. Cult. Ecol. 2008, 12, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, C.V. The evolution of sustainability. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 1992, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prades, J.A.; Tessier, R.; Vaillancourt, J.-G. Instituer le Développement Durable: Éthique de L’écodécision et Sociologie de L’environnement; Fides: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmins, J.P. Ecology, environmentalism and green religion. For. Chron. 1993, 69, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.E. World Religions, the Earth Charter, and Sustainability. Worldviews Glob. Relig. Cult. Ecol. 2008, 12, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratosin, S.; Tudor, M.A. Religion(s), laïcité(s) et société(s) au tournant des humanités numériques; Iarsic: Les Arcs, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bratosin, S.; Jauffret, M. Le mythe politique français de la laïcité: foi et sens politique. In Politique et religion au défi de la communication numérique; Tudor, M.A., Clitan, G., Grilo Marat, M., Eds.; l’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tudor, M.A.; Bratosin, S. The Romanian Religious Media Landscape: Between Secularization and the Revitalization of Religion. J. Rel. Media Digit. Cult. 2018, 7, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altheide, D.L. Media logic, social control, and fear. Commun. Theory 2013, 23, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampuja, M.; Koivisto, J.; Väliverronen, E. Strong and Weak Forms of Mediatization Theory. A Critical Review. Nord. Rev. 2014, 36, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Asp, K. Medialization, media logic and mediarchy. Nord. Rev. 1990, 11, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bratosin, S.; Gomes, P.-D.; Neto, F.A. Mediatization of religion and power. Ess. J. Comm. Stud. 2017, 10, 5–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bratosin, S. La médialisation du religieux dans la théorie du post néo-protestantisme. Soc. Comp. 2016, 63, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N. Mediatization or mediation? Alternative understandings of the emergent space of digital storytelling. New Med. Soc. 2008, 10, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N.; Hepp, A. Conceptualising Mediatization: Contexts, Traditions, Arguments. Commun. Theory 2013, 23, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, D.; Stanyer, J. Mediatization: Key concept or conceptual bandwagon? Media Cult. Soc. 2014, 36, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.G. Mediatization: A concept, multiple voices. ESSACHESS J. Commun. Stud. 2016, 9, 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, P.G. A Midiatização no Processo Social; PPGcom: São Leopoldo, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hepp, A. Cultures of Mediatization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, S.P. The Mediatization of Society. A Theory of the Media as Agents of Social and Cultural Change. Nord. Review. 2008, 29, 105–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, S.P. The Mediatization of Culture and Society; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kiousis, S. Explicating media salience: A factor analysis of New York Times issue coverage during the 2000 US presidential election. J. Commun. 2004, 54, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krotz, F. Elektronisch mediatisierte kommunikation. Überlegungen Konzept. Einiger Zukünftiger Forsch. Kommun. Rundfunk Fernseh. 1995, 43, 445–462. [Google Scholar]

- Krotz, F. Der Symbolische Interaktionismus und die Kommunikationsforschung Zum hoffnungsvollen Stand einer schwierigen Beziehung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krotz, F. Mediatisierung. Fallstud. zum Wan. von Komm; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Laurendeau, N.M. An Energy Primer: From Thermodynamics to Theology. Zygon® 2011, 46, 890–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövheim, M.; Lundmark, E. Gender, Religion and Authority in Digital Media. ESSACHESS-J. Commun. Stud. 2019, 12, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lundby, K. Mediatization: Concept, Changes, Consequences; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lundby, K. Mediatization of Communication; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2014; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Lunt, P.; Livingstone, S. Is ‘mediatization’ the new paradigm for our field? A commentary on Deacon and Stanyer (2014, 2015) and Hepp, Hjarvard and Lundby (2015). Med. Cult. Soc. 2016, 38, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, M.A.; Bratosin, S. Croire en la technologie: Médiatisation du futur et futur de la médiatisation; Iarsic: Les Arcs, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tudor, M.A. Multimédiatisation et événement religieux: le cas de la campagne d’évangélisation l’Horizon de l’espérance de Hope Channel Romania (Speranta TV). Tic et Soc. 2015, 9, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krotz, F. Mediatization: A concept with which to grasp media and societal change. In Mediatization: Concept, Changes, Consequences; Lundby, K., Ed.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Krotz, F. Explaining the Mediatisation Approach. Javn.-The Public 2017, 24, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuze, M. Media Life. Media Cult. Soc. 2011, 33, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, W. Reconstructing mediatization as an analytical concept. Eur. J. Commun. 2004, 19, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. What is wrong with social theory? Amer. Sociol. Rev. 1954, 18, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.H. Faith in Science in Global Perspective: Implications for Transhumanism. Public Underst. Sci. 2014, 23, 814–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothenbuhler, E.W.; Coman, M. Media Anthropology; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stout, D.A. Media and Religion. Foundations of an Emerging Field; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Debray, R. L’Emprise; Gallimard: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rieder, B.; Röhle, T. Digital methods: Five challenges. In Understanding digital humanities; Berry, D.M., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Discourse and Social Change; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Language and Power; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bozorova, M. Coverage of the problem of human trafficking in the media: Content analysis of materials of editions of Russian Federation. ESSACHESS J. Commun. Stud. 2019, 12, 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gallot, L. L’influence des médias sur la société. Available online: https://www.journaldunet.com/management/expert/62682/l-influence-des-medias-sur-la-societe.shtml (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Fromages, E. L’horloge de l’apocalypse s’avance vers la fin du monde. Available online: https://www.sciencesetavenir.fr/nature-environnement/fin-du-monde-il-est-minuit-moins-deux-minutes-sur-l-horloge-de-l-apocalypse120217 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- UNDP. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/fr/home/sustainable-development-goals.html (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- MAIF. Des produits de placements responsables. 2018. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/l-epargne-solidaire/article/2018/11/08/des-produits-de-placementsresponsables53808865380848.html (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Vincent, A. Du Stella McCartney homme: Promesse d’une mode masculine éco-responsible. Available online: https://www.lefigaro.fr/mode-homme/2016/02/18/30007-20160218ARTFIG00213-du-stella-mccartney-homme-promesse-d-une-mode-masculine-eco-responsable.php (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Peirce, C.S. Comment rendre nos idées claires. Rev. Philos. 1879, 7, 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Viau, M. Pragmatisme et théologie pratique. Rev. Théol. Philos. 1992, 124, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet, A. Renoncer à faire des enfants pour la planète, l’étrange combat des femmes “ginks”. Available online: https://www.20minutes.fr/planete/699029-20110401-planete-renoncer-faire-enfants-planete-etrange-combat-femmes-ginks (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Peyret, E.; Delmas, A.; Deborde, J. Alimentation: Sus au pourri gâché, Libération. 2018. Available online: https://www.liberation.fr/evenements-libe/2018/10/30/alimentation-sus-au-pourri-gache1688913 (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Moltmann, J. Dieu dans la création. In Traité Ecologique de la Creation; Cerf: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, M. Scientific Representation. Philos. Compass 2010, 5, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.F. Religion and Sustainability: Social Movements and the Politics of the Environment; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, D.; Barkemeyer, R. Media coverage of sustainable development issues - attention cycles or punctuated equilibrium? Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, S.; Poulain, M. La spiritualité: Émergence d’une tendance dans la consommation. Manag. Avenir 2008, 5, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, F. Thérapies et nouvelles spiritualités. Sci. Hum. 2000, 106, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, P. Sensing Religion, Observing Religion, Reconstructing Religion: Contingency and Pluralization in Post-Westphalian Context. Soc. Comp. 2016, 63, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieffel, R. Journalistes et intellectuels: Une nouvelle configuration culturelle? Réseaux Commun. Technol. Société 1992, 51, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyrowitz, J. Understandings of media. ETC Rev. Gen. Semant. 1999, 56, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mihaela Alexandra, T.; Stefan, B. French Media Representations towards Sustainability: Education and Information through Mythical-Religious References. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052095

Mihaela Alexandra T, Stefan B. French Media Representations towards Sustainability: Education and Information through Mythical-Religious References. Sustainability. 2020; 12(5):2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052095

Chicago/Turabian StyleMihaela Alexandra, Tudor, and Bratosin Stefan. 2020. "French Media Representations towards Sustainability: Education and Information through Mythical-Religious References" Sustainability 12, no. 5: 2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052095

APA StyleMihaela Alexandra, T., & Stefan, B. (2020). French Media Representations towards Sustainability: Education and Information through Mythical-Religious References. Sustainability, 12(5), 2095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052095