I Am a Leader, I Am a Mother, I Can Do This! The Moderated Mediation of Psychological Capital, Work–Family Conflict, and Having Children on Well-Being of Women Leaders

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Job Characteristics and Well-Being

1.1.2. Personal Resources (PsyCap) and Well-Being

1.1.3. Work–Family Interference and Well-Being

1.1.4. Having Children and Well-Being

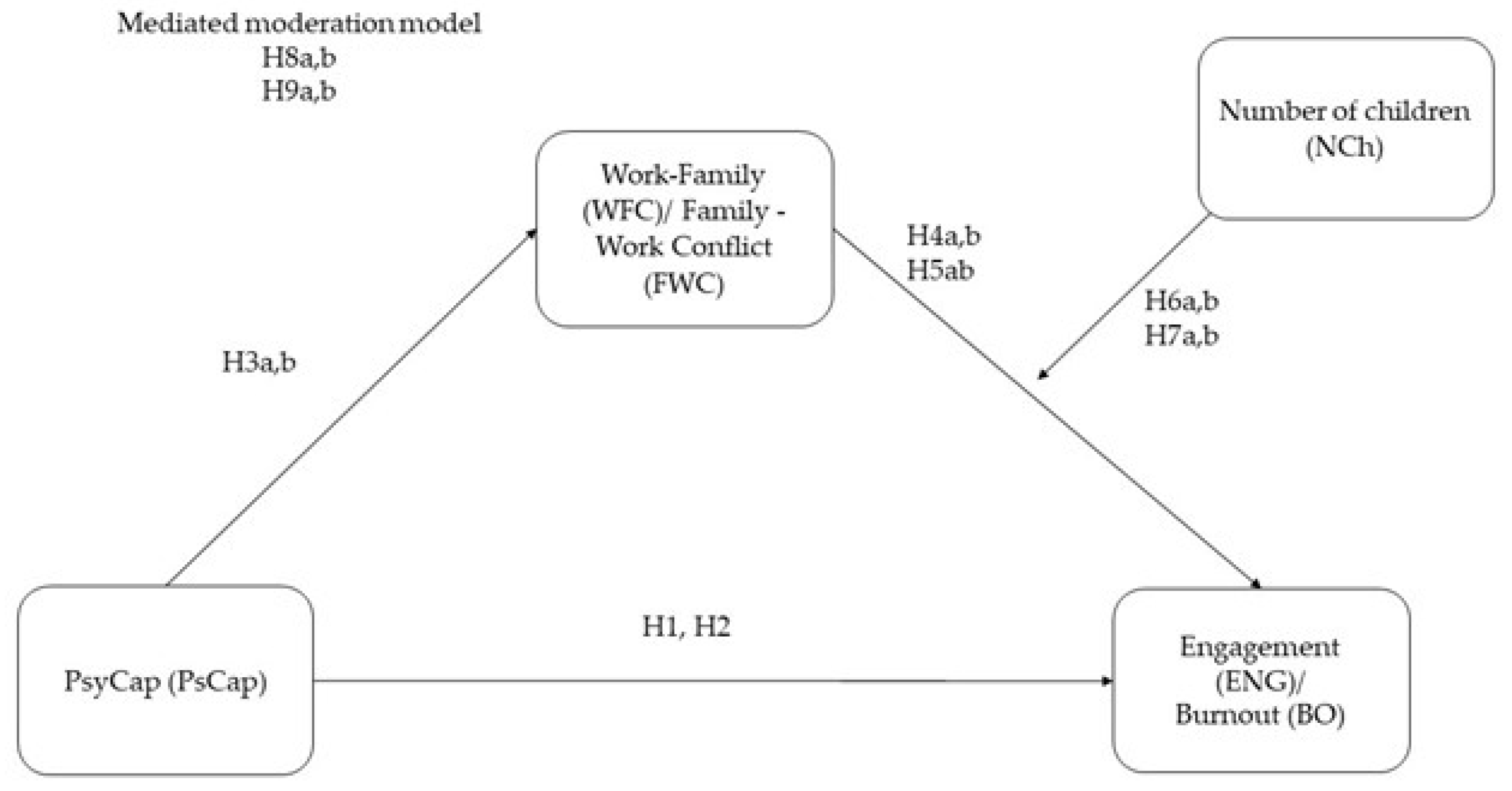

1.1.5. Proposed Model

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Psychological Capital

2.3.2. Engagement

2.3.3. Burnout

2.3.4. Family–Work Conflict

2.3.5. Work–Family Conflict

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussions

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haar, J.; Carr, S.C.; Arrowsmith, J.; Parker, J.; Hodgetts, D.; Alefaio-Tugia, S. Escape from working poverty: Steps toward sustainable livelihood. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive healthy organizations: Promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Sparks, K.; Faragher, B.; Cooper, C. Well-being and occupational health in the 21st century workplace. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2001, 74, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferradás, M.d.M.; Freire, C.; García-Bértoa, A.; Núñez, J.C.; Rodríguez, S. Teacher profiles of psychological capital and their relationship with burnout. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Tsai, C.H.; Tsai, F.S.; Huang, W.; de la Cruz, S.M. Psychological capital research: A meta-analysis and implications for management sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, R.; Fazi, L.; Guglielmi, D.; Mariani, M.G. Enhancing substainability: Psychological capital, perceived employability, and job insecurity in different work contract conditions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, A.; Constant, A.; Giulietti, C.; Guzi, M. Ethnic diversity and well-being. J. Popul. Econ. 2017, 30, 265–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Kenny, M.E. The contributions of emotional intelligence and social support for adaptive career progress among italian youth. J. Career Dev. 2015, 42, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. Constructing and Managing Personal Project, Career Project, Life Project: The Challenge of Sustainability; Invited lecture at the Seminar Organized by the Faculty of Health Sciences; Hokkaido University: Sapporo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guichard, J. Career guidance, education, and dialogues for a fair and sustainable human development. In Proceedings of the Inaugural Conference of the UNESCO Chair of Lifelong Guidance and Counselling, Wroclaw, Poland, 26–27 November 2013; University of Wroclaw: Wroclaw, Poland, 2013; pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Matud, M.P.; López-Curbelo, M.; Fortes, D. Gender and psychological well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 109, 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzubinski, L.; Diehl, A.; Taylor, M. Women’s ways of leading: The environmental effect. Gend. Manag. 2019, 34, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Carli, L.L. Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, S.M.; Robinson, J.P.; Milkie, M.A. Changing Rhythms of American Family Life; Russell Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 249, pp. 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, S.; Sharma, R.R. Enhancing Women’s well-being: The role of psychological capital and perceived gender equity, with social support as a moderator and commitment as a mediator. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F.M.; Halpern, D.F. Women at the top: Powerful leaders define success as work + family in a culture of gender. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, Z.Y.; Wanzenried, G. Do management jobs make women happier as well? empirical evidence for switzerland. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2019, 8, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital and Beyond; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 19–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bouckenooghe, D.; De Clercq, D.; Raja, U. A person-centered, latent profile analysis of psychological capital. Aust. J. Manag. 2019, 44, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, H.K.; Ducharme, L.J.; Roman, P.M. Turnover Intention and emotional exhaustion “at the top”: Adapting the job demands-resources model to leaders of addiction treatment organizations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D. Creativity and charisma among female leaders: The role of resources and work engagement. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2760–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.; Bosch, A.; Becker, J. Retention of women accountants: The interaction of job demands and job resources. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B. An evidence-based model of work engagement. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Euwema, M.C. Job Resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; van Veldhoven, M.; Xanthopoulou, D. Beyond the demand-control model: Thriving on high job demands and resources. J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Dollard, M.F.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Schreurs, P.J.G. When Do job demands particularly predict burnout? The moderating role of job resources. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 766–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Hou, H.; Ma, R.; Sang, J. The effect of psychological capital between work–family conflict and job burnout in chinese university teachers: Testing for mediation and moderation. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Fischbach, A. Work engagement among employees facing emotional demands: The role of personal resources. J. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 12, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, O.L. Psychological capital, work well-being, and work-life balance among chinese employees: A cross-lagged analysis. J. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 12, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitichat, T.; Reichard, R.J.; Kea-Edwards, A.; Middleton, E.; Norman, S.M. Psychological capital for leader development. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youseff, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 3–143. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, R.C.; Cheng, H.L.; Wong, J.; Booth, N.; Jones, Z.; Sevig, T. Hope for help-seeking: A positive psychology perspective of psychological help-seeking intentions. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 45, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaven, P.; Ciarrochi, J. Parental Styles, gender and the development of hope and self-esteem. Eur. J. Personal. 2008, 22, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.Y. Self-efficacy beliefs and their sources in undergraduate computing disciplines: An examination of gender and persistence. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2016, 53, 540–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabras, C.; Mondo, M. Coping strategies, optimism, and life satisfaction among first-year university students in italy: Gender and age differences. High. Educ. 2018, 75, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J.A.D.; King, R.B.; Valdez, J.P.M. Psychological capital bolsters motivation, engagement, and achievement: Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Fu, J.; Wang, L. Work-family conflict and burnout among chinese female nurses: The mediating effect of psychological capital. BMC Public Health 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Karadas, G. The effect of psychological capital on conflicts in the work-family interface, turnover and absence intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 43, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bouwman, K.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Job resources buffer the impact of work-family conflict on absenteeism in female employees. J. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 10, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, R.; Song, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, D. The impact of psychological capital on job burnout of Chinese nurses: The mediator role of organizational commitment. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. Work-family conflict and burnout among Chinese doctors: The mediating role of psychological capital. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, M.; Haar, J.M.; Luthans, F. The role of mindfulness and psychological capital on the well-being of leaders. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, M.; Hansez, I.; Chmiel, N.; Demerouti, E. Performance expectations, personal resources, and job resources: How do they predict work engagement? Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; van der Heijden, F.M.M.A.; Prins, J.T. Workaholism, burnout and well-being among junior doctors: The mediating role of role conflict. Work Stress 2009, 23, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Williams, L.J. Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 56, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; DeLongis, A.; Kessler, R.C.; Wethington, E. The contagion of stress across multiple roles. J. Marriage Fam. 1989, 51, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, M. Crossover of Stress and strain in the family and at the workplace crossover—A theoretical perspective. In Historical and Current Perspectives on Stress and Health (Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being, Vol. 2); Perrewe, P., Ganster, D., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2002; pp. 143–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Dollard, M.F. How job demands affect partners’ experience of exhaustion: Integrating work-family conflict and crossover theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voydanoff, P. Consequences of boundary-spanning demands and resources for work-to-family conflict and perceived stress. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, W.B.; Crouter, A.C. Longitudinal associations between maternal work stress, negative work-family spillover, and depressive symptoms. Fam. Relat. 2009, 58, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Cropanzano, R. The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D.S.; Perrewé, P.L. The role of social support in the stressor-strain relationship: An examination of work-family conflict. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeva, A.Z.; Chiu, R.K.; Greenhaus, J.H. Negative affectivity, role stress, and work-family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Prins, J.T.; der Heijden, F.M.v. Applying the job demands-resources model to the work-home interface: A study among medical residents and their partners. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislieri, C.; Emanuel, F.; Molino, M.; Cortese, C.G.; Colombo, L. New technologies smart, or harm work-family boundaries management? Gender differences in conflict and enrichment using the JD-R theory. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Bulters, A.J. The loss spiral of work pressure, work-home interference and exhaustion: Reciprocal relations in a three-wave study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W.; van der Heijden, B.I.J.M. Perspective: The role of demands and resources. Int. J. Psychol. 2012, 47, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J.; Weir, T.; DuWors, R.E. Type A behavior of administrators and wives’ reports of marital satisfaction and well-being. J. Appl. Psychol. 1979, 64, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedeian, A.G.; Burke, B.G.; Moffett, R.G. Outcomes of work-family conflict among married male and female professionals. J. Manag. 1988, 14, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.F.; Voydanoff, P. Work/family role strain among employed parents. Fam. Relat. 1985, 34, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Kotrba, L.M.; Mitchelson, J.K.; Clark, M.A.; Baltes, B.B. Antecedents of work-family conflict: A meta-analytic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 689–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, A.; Mencarini, L.; Vignoli, D. Work–family conflict moderates the relationship between childbearing and subjective well-being. Eur. J. Popul. 2016, 32, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooklin, A.R.; Dinh, H.; Strazdins, L.; Westrupp, E.; Leach, L.S.; Nicholson, J.M. Change and stability in work-family conflict and mothers’ and fathers’ mental health: Longitudinal evidence from an australian cohort. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 155, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, R.D. Development in the family. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 365–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.E.; Hatmaker, D.M. Individual Stresses and strains in the ascent to leadership: Gender, work, and family. In Handbook of Research on Gender and Leadership; Madsen, S., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Chetelham, UK, 2017; pp. 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein-Bercovitz, H.; Frish-Burstein, S.; Benjamin, B.A. The role of personal resources in work-family conflict: Implications for young mothers’ well-being. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. Effective leadership behavior: What we know and what questions need more attention. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 26, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2006; pp. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, J.P.; Heaphy, E.D.; Carmeli, A.; Spreitzer, G.M.; Dutton, J.E. Relationship quality and virtuousness: Emotional carrying capacity as a source of individual and team resilience. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2013, 4, 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, A.; Guinot, J.; Chiva, R.; López-Cabrales, Á. How to Emerge stronger: Antecedents and consequences of organizational resilience. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction part of the management sciences and quantitative methods commons. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Núñez, M.I.; De Jesús, S.N.; Viseu, J.; Santana-Cárdenas, S. Psychological capital of spanish workers: Confirmatory factor analysis of PCQ-12. Rev. Iberoam. Diagnostico Y Eval. Psicol. 2018, 3, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; Gonzalez-Roma, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Exposure to information technology and its relation to burnout. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2000, 19, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.L.; Eddleston, K.A.; Veiga, J.F. Moderators of the relationship between work-family conflict and career satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 77–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Gardner, D.G. Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W.; van der Heijden, B.I. Work–family interface from a life and career stage perspective: The role of demands and resources. Int. J. Psychol. 2012, 47, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, A.; Dzubinski, L. An overview of gender-based leadership barriers. In Handbook of Research on Gender and Leadership; Madsen, S.R., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Chetelham, UK, 2017; pp. 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratberg, E.; Dahl, S.Å.; Risa, A.E. ‘The double burden’: Do combinations of career and family obligations increase sickness absence among women? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2002, 18, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastekaasa, A. Dependent Children and Women’s Sickness Absence in the EU Countries and Norway. Eur. Soc. 2013, 15, 686–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz, M. Estrategias de Conciliación y Segmentación Social: La Doble Desigualdad. Sociol. Probl. Prat. 2013, 73, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm-Burns, M.A.; Spivey, C.A.; Hagemann, T.; Josephson, M.A. Women in Leadership and the Bewildering Glass Ceiling. Am. J. Health Pharm. 2017, 74, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T., Jr. Creating the Multicultural Organization: A Strategy for Capturing the Power of Diversity; Jossey-Bass: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson, D.; Fletcher, J.K. A modest manifesto for shattering the glass ceiling. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzer Carr, B.; Ben Hagai, E.; Zurbriggen, E.L. Queering Bem: Theoretical intersections between Sandra Bem’s scholarship and queer theory. Sex. Roles 2017, 76, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfrey, L.; Twine, F.W. Gender-fluid geek girls: Negotiating inequality regimes in the tech industry. Gend. Soc. 2017, 31, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, A.E.; Portillo, S. Not a woman, but a soldier: Exploring identity through translocational positionality. Sex. Roles 2017, 76, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, P.; Winkler, B.; Dunkl, A. Creating a healthy working environment with leadership: The concept of health-promoting leadership. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 2430–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Range | Intercorrelations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | Min | Max | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Predictor | 1. PsyCap | 5.86 | 0.57 | 3.87 | 6.00 | 0.88 | 1 | ||||

| Mediator | 2. FWC | 3.86 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 6.75 | 0.72 | −0.17 * | 1 | |||

| 3. WFC | 2.79 | 1.49 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 0.86 | −0.09 | 0.04 ** | 1 | |||

| Moderator | 4. NCh | 2.04 | 1.33 | 0.00 | 6.00 | −0.06 | −0.00 | −0.02 | 1 | ||

| Criterion | 5. ENG | 6.00 | 1.07 | 3.11 | 7.00 | 0.88 | 0.40 ** | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 1 |

| 6. BO | 2.65 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 0.82 | −0.39 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.13 | 0.04 | −0.44 ** | |

| Work–Family Conflict (M) | Engagement (Y) | Burnout (Y) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient | 95% CI | Coefficient | 95% CI | |||||||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||||

| Psychological Capital (X) | a1 --> | −0.43 (0.17) * | −0.78 | −0,09 | c’ --> | 0.62 (0.09) *** | 0.43 | 0.80 | c’ --> | −0.61 (0.12) *** | −0.84 | −0.38 | ||

| Work–Family Conflict (M) | b1 --> | 0.05 (0.04) | −0.02 | 0.12 | b1 --> | 0.26 (0.05) *** | 0.17 | 0.35 | ||||||

| Number of Children (W) | b2 --> | 0.06 (0.04) | −0.02 | 0.13 | b2 --> | 0.03 (0.05) | −0.07 | 0.12 | ||||||

| M x W | b3 --> | −0.07 (0.03) * | −0.13 | −0.02 | b3 --> | 0.08 (0.04) * | 0.01 | 0.15 | ||||||

| Constant | iM --> | 2.53 (1.03) * | 0.49 | 4.56 | iY --> | 2.38 (0.55) *** | 1.29 | 3.47 | iY --> | 6.23 (0.68) *** | 4.88 | 7.57 | ||

| R2 = 0.03 | R2 = 0.21 | R2 = 0.28 | ||||||||||||

| F (1,198) = 6.07, p = 0.01 | F (4,195) = 12.67, p < 0.001 | F (4,195) = 18.82, p < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Index of moderated mediation | Index of moderated mediation | |||||||||||||

| Index | Bootstrap SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | Index | Bootstrap SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |||||||

| a1, b3 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.08 | a1, b3 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.00 | |||||

| Family–Work Conflict (M) | Engagement (Y) | Burnout (Y) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient | 95% CI | Coefficient | 95% CI | ||||||||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | ||||||||||

| Psychological Capital (X) | a1 --> | −0.22 (0.19) | −0.60 | 0.16 | c’ --> | 0.59 (0.10) *** | 0.39 | 0.79 | c’ --> | −0.76 (0.13) *** | −1.01 | −0.50 | |||

| Family–Work Conflict (M) | b1 --> | −0.03 (0.04) | −0.11 | 0.05 | b1 --> | 0.07 (0.05) | −0.03 | 0.17 | |||||||

| Number of Children (W) | b2 --> | 0.06 (0.04) | −0.03 | 0.14 | b2 --> | 0.05 (0.05) | −0.06 | 0.15 | |||||||

| M x W | b3 --> | 0.03 (0.03) | −0.03 | 0.09 | b3 --> | 0.05 (0.04) | −0.03 | 0.13 | |||||||

| Constant | iM --> | 1.29 (1.12) | −0.93 | 3.50 | iY --> | 2.55 (0.59) *** | 1.38 | 3.72 | iY --> | 7.06 (0.76) *** | 5.56 | 8.55 | |||

| R2 = 0.01 | R2 = 0.19 | R2 = 0.18 | |||||||||||||

| F (1,176)=1.33, p = 0.25 | F (4,173) = 9.90, p < 0.001 | F (4,173) = 9.76, p < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

| Index of moderated mediation | Index of moderated mediation | ||||||||||||||

| Index | Bootstrap SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | Index | Bootstrap SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||||||||

| a1, b3 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.5 | 0.01 | a1, b3 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.6 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Engagement | Burnout | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels of Moderator | Effects | Boot SE | Boot CI | Effects | Boot SE | Boot CI | ||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

| Number of children | −1 SD | −1.35 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.15 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.16 | 0.00 |

| Mean | 0 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.05 | −0.22 | −0.01 | |

| +1 SD | 1.35 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.16 | 0.08 | −0.34 | −0.02 | |

| Engagement | Burnout | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels of Moderator | Effects | Boot SE | Boot CI | Effects | Boot SE | Boot CI | ||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

| Number of children | −1 SD | −1.37 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| Mean | 0 | 0.1 | 0.02 | −0.20 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.02 | |

| +1 SD | 1.37 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.14 | 0.05 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Machín-Rincón, L.; Cifre, E.; Domínguez-Castillo, P.; Segovia-Pérez, M. I Am a Leader, I Am a Mother, I Can Do This! The Moderated Mediation of Psychological Capital, Work–Family Conflict, and Having Children on Well-Being of Women Leaders. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2100. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052100

Machín-Rincón L, Cifre E, Domínguez-Castillo P, Segovia-Pérez M. I Am a Leader, I Am a Mother, I Can Do This! The Moderated Mediation of Psychological Capital, Work–Family Conflict, and Having Children on Well-Being of Women Leaders. Sustainability. 2020; 12(5):2100. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052100

Chicago/Turabian StyleMachín-Rincón, Laritza, Eva Cifre, Pilar Domínguez-Castillo, and Mónica Segovia-Pérez. 2020. "I Am a Leader, I Am a Mother, I Can Do This! The Moderated Mediation of Psychological Capital, Work–Family Conflict, and Having Children on Well-Being of Women Leaders" Sustainability 12, no. 5: 2100. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052100

APA StyleMachín-Rincón, L., Cifre, E., Domínguez-Castillo, P., & Segovia-Pérez, M. (2020). I Am a Leader, I Am a Mother, I Can Do This! The Moderated Mediation of Psychological Capital, Work–Family Conflict, and Having Children on Well-Being of Women Leaders. Sustainability, 12(5), 2100. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052100