Abstract

Online consumer complaints are closely related to business reputation and elicit managers’ persistent efforts. However, service providers in the sharing economy (SE) lack the skills to communicate with consumers because most are informal or nonprofessional property owners. This research aims to examine the relationship between service providers’ responses and prospective consumers’ perceived helpfulness in the SE by using bed and breakfasts (B&B) as the sample. Response length and voice are adopted to measure the content quality of B&B’s response to an online complaint. Three types of voices (defensive, formalistic, and accommodative) are identified by analyzing service providers’ responses to negative reviews, among which the accommodative voice with empathic statements is the most effective. An inverted-U curve relationship between response length and helpfulness votes is verified based on cognitive load theory. Moreover, interactive effects between response length, review length, and images are also examined. This study suggests the investigation of online reviews from comprehensive perspectives, as well as the adoption of personalized strategies by SE practitioners to respond to consumer complaints.

1. Introduction

Word of mouth (WOM) can facilitate consumers’ purchase decision processes by reducing their perceived uncertainties and risks [1,2,3]. In the Web 2.0 context, WOM has evolved into electronic WOM (eWOM), which spreads widely and rapidly. Online product reviews from the perspective of consumers, which are the main forms of eWOM, provide reference information to prospective consumers to evaluate products and services [4]. By writing online reviews, consumers can express their satisfaction of a product or service and share their consumption experiences with other consumers [5]. Studies have widely examined the impact of online reviews on consumers’ purchase decisions and business sales [6,7]. According to the negativity bias, negative reviews are more memorable than positive ones, and therefore generate stronger impact because they are considered more diagnostic and informative [4,8,9,10]. Negative eWOM that remain on a platform for a considerable amount of time leave a lasting impression on a business’ reputation and affect their performance metrics, such as online bookings and room sales of hotels [11,12]. Thus, hoteliers have become aware of the need to actively communicate with consumers by responding to their reviews [13,14]. A manager’s proper response to a consumer’s complaint or negative review can not only resolve a problem posted by the reviewer but also show prospective consumers the importance that the hotel places on them [15].

The sharing economy (SE) is a contested concept, which is promoted by practitioners, industry associations, policymakers, and academics because of its purported sustainability potential [16]. Despite the controversy, the SE is expanding rapidly in developing countries [17]. In the context of electronic commerce, the SE mainly refers to digitized platforms for peer-to-peer exchanges [18,19,20,21,22]. Generally, these types of exchanges involve service providers, platforms, and consumers [23], among which the platforms form the basis of interactions. However, SE platforms have been accused of failing to provide sufficient protection to users, including service suppliers and consumers, and treating workers as contractors [24]. Platforms do not train service providers on how to manage their reputation but offer only reputation-related cues. The reputation of service providers is believed to be helpful in ensuring the security of online transactions [25] and in enhancing mutual trust between consumers and service providers [26]. Thus, providing actionable recommendations for SE service providers to manage their online reputations, particularly negative eWOM that can damage their business image, is necessary.

As a means to manage online reputation, managerial response to online reviews has yet been discussed in the SE context. However, this response has been examined to significantly influence hotel rankings, sales, and consumers’ intentions to write reviews in the hotel service literature [27]. Moreover, managerial responses not only increase future satisfaction of the complaining consumers [28] but also moderate the influence of hotel ratings and volume of eWOM on the later consumers’ purchase decision [29]. The quantity (cumulative percentage of managerial response) and quality (response strategies) aspects of managerial response have a significant relationship with hotels’ competitive performance [30]. Specifically for negative reviews, the source of the response (the general manager or guest service agent), the voice of the responder (professional or conversational human voice), and the speed of the response (fast, moderate, or slow) will lead to different consumer inferences about hotels’ customer concern and trustfulness which may, in turn, influence their purchase intention [12]. When responding to negative reviews, appropriate response strategies can engender the consumers’ positive attitude toward the hotel. Specifically, accommodative strategies (putting complainers’ concerns first) have a stronger positive impact on consumers’ evaluation of the hotel than defensive or no action strategies [31]. Furthermore, responses containing empathy statements to negative reviews will cause prospective consumers to evaluate the responses more favorably than those without [10].

Prior studies proposed some effective approaches for responding to negative reviews based on different attributes of managerial response in the hotel service context in which managers or customer service personnel generally have been equipped with the knowledge for managing consumer’s complaints. However, service providers in the SE, a relatively informal and nonprofessional-based market [14,32], generally lack adequate customer complaint management skills and the measures to evaluate their reputation management strategy. Given this, this research aims to examine the effectiveness of managerial responses in the SE by using the evidence from bed and breakfasts (B&Bs, a travel accommodation sharing service that is generally provided by private property owners) [32], which is a well-known sector in the SE. The following questions must be addressed to achieve the objective of this study:

Question 1.

How do B&Bs respond to negative online consumer reviews?

Question 2.

What is the relationship between B&B responses and consumers’ perceived helpfulness?

Question 3.

How should B&Bs respond to negative reviews effectively?

First, this research will briefly review previous studies on online product reviews and management responses. Second, a qualitative study will be designed based on the literature to discuss B&B behaviors when responding to consumer complaints. Third, empirical studies will be conducted to investigate the relationship between B&B responses and prospective consumers’ perceived helpfulness. Finally, implications and suggestions for practice will be generated based on the research findings.

2. Literature Review

The effort of service recovery is often evaluated via the perceptions of justice framework [33]. According to the interactional justice theory (IJT), consumers’ perceptions of the fairness of service providers’ behaviors toward consumer complaints represent the positive image of the service provider and the high perceived value of the service [34,35]. The manner in which a complaint is dealt with can be more critical and impressive than the service failure itself [10]. Given this situation, most service providers recognize the importance of responding to online negative eWOM. According to the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), persuasion can be induced through a central route based on the strength of arguments presented in a message or through a peripheral route based on cues in and around the message [36]. In online interactions, the presence and the speed of business responses to negative eWOM can be the cues to evaluate how the service provider cares for their consumer, whereas the information and empathic statements in the responses can be regarded as the argument strength. This research presents a brief review of online reviews and managerial responses, which have been extensively studied in other areas, to examine how this influencing mechanism works in the SE.

2.1. Online Product Reviews

Information on products and services can facilitate consumers’ decision-making processes. A comparison with offline consumers shows that online consumers are exposed to two types of information, namely, seller-created information through e-commerce platforms and user-generated content or online product reviews. An online product review by a prior consumer plays a dual role as an informant and a recommender [37]. As an informant, the review presents product information from the perspective of a consumer, whereas as a recommender, it shows prior consumers’ recommendation intentions as eWOM. A prospective consumer can acquire user-oriented product information from words and images contained in a review and decide whether or not to purchase. In other words, online product reviews can influence consumers’ product attitudes and behavioral intentions to a large extent [38].

Consumers post online reviews to share their experiences and express their satisfaction with products and services [39]. Affective commitment or concern for the company or brand can also drive consumers to deliver eWOM [40]. While some of the reviews are positive, a large number of negative ones expressing consumer dissatisfaction also exists. Responding to negative reviews appropriately is considered as “customer care” and “service recovery” [41]. However, individuals’ perceptions of satisfaction differ. Some negative reviews are not objective and are extremely unfair [12]. Given this situation, managerial responses to negative reviews provide sellers and service providers with the opportunity to express their opinions regarding the experience. Thus, a comprehensive approach for understanding online reviews should consider not only product reviews but also reviewer characteristics and seller responses.

2.1.1. Argument Quality of Online Reviews

Argument quality is the strength or plausibility of arguments in an informational message [42]. Argument quality is regarded as a critical factor which affects a consumer’s evaluation of a persuasive message [43]. Moreover, it has been used to highlight the influence of perceived believability of received information on an individual’s behavior [44]. Consumers expect to evaluate online reviews created by other users based on the clues embedded in the information. Reviews with relevant, objective, and verifiable arguments are likely to be persuasive and informative. In other words, consumers’ perceived relevance and the comprehensiveness of an online review are positively associated with perceived helpfulness of a review and the likelihood of review adoption [43,45].

The quality of persuasive argument is interpreted by two dimensions, namely, the argument valence and the argument strength [46], which are reflected by the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of online reviews [47]. Quantitative characteristics refer to star rating reviews, whereas qualitative characteristics refer to content reviews. Star ratings reflect prior consumers’ attitudes and satisfaction levels, which in turn help prospective consumers to evaluate products [48]. Star ratings as numerical indicators use five-point star recommendations for surface-level reviews and product assessments [49]. The relevance, comprehensiveness, and readability of review contents are the qualitative characteristics of an online review. These characteristics can be perceived by consumers from the words and images of the reviews. Although the contents of reviews are qualitative, such characteristics have been measured using quantitative indices, such as review length and image count [50,51]. As the main indicators of the content of an online review, review length and images are revealed to significantly influence perceived helpfulness [47].

2.1.2. Source Credibility of Online Reviews

The source credibility of an online review refers to the extent to which a reviewer is perceived as a credible source of information for the product and can be trusted to provide an objective judgment [52]. Credibility is an important concept with regard to the persuasiveness and trustworthiness of WOM because the information receiver’s perceived credibility can change their attitude toward the information presented [43]. In traditional WOM, information receivers can use verbal and nonverbal communication cues to infer source credibility during face-to-face conversations with referrals, friends, and family members [53]. Online product reviews are written by anonymous users who have no actual relationships with information receivers [54]. However, consumers can assess the credibility of a reviewer by evaluating his/her expertise and analyzing the cues in their profile.

A reviewer’s expertise refers to the extent to which an information source is perceived to be capable of creating accurate judgment based on their professional knowledge and skills [55]. Sources with high expertise are considered more persuasive than those with low expertise in inducing positive attitudes and behavioral changes [56]. Despite the reviewers’ limited social backgrounds and attributes in online shopping environments, consumers can still evaluate reviewer expertise based on past behaviors [57]. Reviewers’ experiences, such as number of written reviews and earned cumulative helpfulness, are significant predictors of review helpfulness [51].

The importance of identity disclosure in online interactions has also been demonstrated [58], which can reduce consumers’ uncertainties when searching for information online [53]. Message recipients can use the personal information disclosed by message creators in their profiles as heuristic cues to evaluate the credibility of the message [59]. Thus, reviewers who disclose personal information in their profiles can increase the credibility of their product reviews and in turn increase its perceived helpfulness [47]. Online profiles are generated using two approaches, namely, users and systems [43]. A comparison with system-generated profiles shows that self-generated profiles more often include users’ real personal information and reflect their actual attitudes. Reviewers’ names and photos as basic personal information have positive relationships with information receivers’ perceived credibility of their online product reviews [60].

2.2. Managerial Responses to Online Reviews

In recent years, online review systems have evolved into IT-enabled customer service systems capable of communication and interaction [61]. Firms can collect consumer information and respond to comments [30]. Responding to online reviews is regarded as supporting customer relationships, reputation, and brand management [15,62]. Managerial responses are publicly available online and can be accessed by potential consumers; thus, they can help review readers perceive a firm’s customer orientation strategies [30].

2.2.1. Responses to Negative Reviews

Dissatisfied consumers can post negative reviews of high-quality products and services [63]. Firms that receive negative reviews can resolve consumer dissatisfaction through private telephone calls or online chats. However, these complaint-handling approaches cannot be observed by prospective consumers [64]. By responding to negative reviews publicly, a firm can demonstrate its concern for consumers and reduce information asymmetry for prospective consumers who lack decision-making knowledge and experience [27]. Negative reviews can remain on websites for a considerable amount of time, thus affecting the reputation of the business and subsequently its performance [11,65]. Negative reviews are viewed more and perceived as more helpful as compared with positive reviews [66,67]. Being unresponsive to consumers’ negative reviews can put a company at a disadvantageous position [68]; thus, pursuing effective ways to manage negative eWOM is a formidable challenge for businesses.

2.2.2. Response Strategies

Managerial responses significantly impact a firm’s performance, especially when addressing negative reviews [30]. Unfortunately, no universal response principle exists, and firms must employ various strategies to respond to negative reviews. Politely recognizing and apologizing for reviewer complaints without compensation or correcting action is referred to as the pure apology strategy [69,70]. Providing compensation or undertaking corrective action is regarded as the problem-resolving strategy [31]. On the contrary, managers who only emphasize reasons for service failures and deny responsibility for negative experiences or the existence of negative situations posted by reviewers adopt the defensive strategy [31,69,70]. Managers who remain silent on online platforms and who do not respond to reviews, negative or otherwise, employ the widely known no response strategy [71]. Nevertheless, managerial responses to negative comments increase consumers’ trust toward the firm as well as their purchase intention toward the product [12].

2.2.3. Response Measurement

Managerial responses convey important signals of the firm’s customer orientation strategy, which is strongly linked to improved firm performance and customer complaint [28]. However, not all responses work as expected. The effectiveness of a response can be evaluated based on quantitative and qualitative aspects [41]. The cumulative percentage of managerial responses has a positive effect on a firm’s competitive performance [30]. Similarly, response frequency, which is the number of responses initiated by a hotel within a particular period, also positively affects the volume and average valence of reviews, helpfulness votes, and popularity rankings [27]. Response speed, which refers to how quickly a service provider responds to reviews, influences the effectiveness of signaling in reducing information asymmetry in a few cases while has no significant effects in others [10,27]. Response length, which is measured by word count, discloses the amount of information in the response and is regarded as an important predictor of perceived helpfulness [27]. Response voice is a vital skill for responders. A high-level conversational human voice (versus a professional voice) reassures prospective consumers and generates positive inferences regarding a hotel’s level of trustworthiness and concern for customers [12].

According to the above literature, previous studies investigated the managerial response to online reviews quantitatively and qualitatively. The cumulative percentage of managerial response, response frequency, and response speed are used as quantitative measures to evaluate how frequent and timely service providers respond to consumers’ online complaints [10,12,27,30]. Researchers adopted a strategic perspective to approach the qualitative aspect of the managerial response to negative reviews. An accommodative response strategy encompassing combined explanations, such as apology and a promise of compensation, has a stronger impact on the consumers’ evaluation of the service provider than defensive or no action strategies [31]. Moreover, managers should include empathy and problem paraphrasing statements in their responses to negative reviews [10]. Prior studies explored the importance of the provision and appropriate strategy of managerial response; however, studies focusing on the response content, which is also an information source together with the review content itself, are limited. Response length, which reflects the amount of information conveyed in the response, is proposed as a quantitative measure of the response content [27]. The additional information conveyed by a long response discloses the service in greater detail. Such supplementary information enables prospective consumers to perceive a higher perception of review helpfulness and form a more accurate evaluation of the service. Furthermore, a response voice, which indicates the communication style used in delivering the response, is considered as another attribute of the response content [12]. A conversational human voice results in favorable consumer inference to the hotel as compared with a professional voice (a standard corporate response). An accommodative response voice is when a hotel confesses responsibility for a negative event, expresses remorse, and attempts to remedy the damage. By contrast, a defensive response is when the response involves justification or excuses or even denies responsibility [64]. Drawing on the above hotel service-related studies, the present study will adopt the response length and voice as the measures of the response content. In addition, this study will develop hypotheses to examine the relationships between these variables and consumers’ perceived helpfulness in the SE context.

3. Research Design and Methods

Previous studies used review or argument quality to describe the plausibility or strength of an online review [42]. However, the present study proposes the concept of response quality, which indicates the interpretability and sincerity of a review response. The main purpose of this study is to examine how response quality affects consumers’ perceived helpfulness of online reviews through empirical studies. A crawler based on Python 3.6 was used to collect data from Ctrip.com, which is a Chinese third-party platform for travel products. A total of 24 privately owned B&Bs which have been adopting the response strategy among the B&Bs in China’s Lane in Chengdu were selected as the sample. A total of 3696 reviews posted before 1 October 2017 were collected, 2716 of which had responses.

Ctrip.com displays reviewers’ nicknames, photos, total number of reviews contributed, total number of images posted, and total earned helpfulness votes. The review information contained a star rating, the review content, the time the reviewer checked in, and the time the reviewer posted his/her review. The hotels’ responses to the online reviews contained the contents and the time of the posts (Ctrip.com removed the module of response time in 2018).

3.1. Study 1: Measuring the Content Quality of B&B’s Response

Among the determinants of response effectiveness, response length and voice are features of the response content, whereas the frequency, speed, and cumulative percentage of the managerial responses are features of the firms’ actions. Thus, response length and voice were adopted in this study as the measures of response quality. The word count of a response was used to represent the response length. Content analysis was conducted to measure response voice. First, positive reviews in the collected data were deleted based on the mean (3.8) of the star ratings. We used only the reviews that prompted the hotels’ responses 24 h after posting to further ensure that subsequent visitors (website users) are able to see the reviews and the hotels’ responses and to control the influence of response speed. A total of 707 reviews were left for the final analysis after filtering out the extreme values.

The negative reviews were read independently by two coders who also coded the review responses into the subcategories extended from the response strategies proposed by Sparks et al. [12] and Lui et al. [30]. Sparks et al. (2016) distinguished a conversational human voice from a professional voice to refer to the manner or style in which the managerial response is communicated [12]. Lui et al. (2018) identified more detailed types of responses that hotels use to address negative reviews, including denial, excuse, defensive, apology, confession, changing, and accommodative strategies [30]. Eight subcategories (shown in Table 1) of responses were sorted out by combining the above approaches and precoding 50 responses. The two coders coded all sampled responses, and no new subcategories were generated. The total agreement level between the coders was 0.84 (544 of 707 were consistently coded), which is higher than the benchmark (0.80) recommended for content analysis [72]. Meanwhile, the Scott’s Pi (π) value was used to describe the intercoder reliability in this study. In contrast to the percent agreement, the Scott’s Pi method takes into account the number of categories including the distribution (the agreement proportion in each category) of values across them [73]. The Scott’s Pi value in this study was 0.81, which is higher than the acceptable level (0.70) recommended for content analysis [74]. The coders’ disagreements were resolved through discussions. Considering empathetic and paraphrased statements in the response content [10], we further classifed the eight subcategories of responses into three main voices, namely, defensive, formalistic, and accommodative Table 1.

Table 1.

Coding scheme of B&B’s response voice.

As shown in Table 1, a defensive response voice covered the communication styles that service providers generally used to deny the existence of service failures, make excuses for negative events, or even accuse consumers of their “unreasonable” requirement. A formalistic voice indicates that service providers recognize the importance of responding to negative reviews but only employ perfunctory apologies or a set of automatic responses without sincere confessions or corrective actions. However, if some consumers had a poor experience at a B&B, then this type of management response would be absolutely useless. An accommodative voice with empathic statements is generally adopted by service providers who sincerely consider consumers’ experiences and satisfaction, encompass proper confession of expression, promise for corrective action or compensation.

3.2. Study 2: Examining the Relationship between Response Quality and Perceived Helpfulness

The more information conveyed by a communication medium, the greater its capacity to reduce uncertainty [75]. Long responses initiated by hotels contain more information about the relevant issue and increase prospective consumers’ perceived hotel intention to care for its customers as compared with short responses [27]. Specific information in a response can supplement the information revealed in the review and enable prospective consumers to form a clear and accurate evaluation of the review’s helpfulness [64]. In addition, consumers can leave negative reviews according to various motivations, such as mismatched preference, disconfirmed expectations, unacceptable service failure, need for social appreciation, or self-enhancement, or just constructive suggestions for the service provider [64,76]. For whatever reason, the consumers expect their complaints to be taken seriously and sincerely. The service providers need to figure out the most appropriate approach to communicate. An accommodative response (putting consumers’ concern first) is found to have a stronger impact on the consumers’ evaluation of the service provider than a defensive response [31]. Moreover, responses with empathetic or paraphrased statement satisfy consumers [10]. In other words, the manner or style in which the hotels’ responses are communicated is also important. Hotels’ managerial responses with a high-level conversational human voice (versus a professional voice) result in potential consumers making positive inferences regarding the hotels’ levels of trustworthiness and concern for customers [12]. Thus, we will examine the following assumptions:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Response length has a relationship with consumers’ perceived helpfulness of a review.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Response voice has a relationship with consumers’ perceived helpfulness of a review.

The hotels’ responses to negative reviews provide potential consumers with opportunities to learn about services in a dual channel rather than a single channel (product review). Previous studies on managerial responses to online reviews generally focus on the standalone impact of responses and shed little light on the interaction between online reviews and the hotels’ responses. Encouragingly, Xie et al. [3] verified that responses to online reviews could moderate the influence of the review valence on future hotel performances.

Potential consumers can learn about a hotel’s service quality and trustworthiness based on its responses and reactions to long reviews with complaints. Likewise, consumers can obtain information about the occurrence of different situations captured in images. Negative reviews are viewed more than positive reviews and are also perceived as more useful [66,67,77]. Thus, for low ratings or negative emotional reviews, responses with sufficient explanations to long reviews, especially those with embedded images, help reviewers and potential consumers understand the services. Thus, this study assumes the following:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

The relationship between response length and perceived helpfulness is stronger in reviews with high review length.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

The relationship between response length and perceived helpfulness is stronger in reviews with images than in those without images.

Initiating a personalized response to an altruistic positive review can increase customers’ perceived usefulness of the response, making them likely to agree with the compliment in the review [30]. Likewise, when customer complaints in negative reviews are related to factors which can be controlled by the firm, confessional and empathetic responses lead to high customer trust toward the firm [70]. In other words, if a hotel manager responds to all the complaints in a long review or provides explanations to images in a deeply thoughtful and apologetic voice, it can draw potential consumers to the hotel’s concern about consumers and their experiences. Thus, we assume the following:

Hypothesis H4a (H4a).

The relationship between response voice and perceived helpfulness is stronger in reviews with high review length.

Hypothesis H4b (H4b).

The relationship between response voice and perceived helpfulness is stronger in reviews with images than in those without images.

Control variables, such as review quality and source credibility, were included in the analysis to accurately evaluate the relationships proposed in this study Table 2. The descriptive characteristics of the data for hypotheses testing are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Statement of variables.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

For further analysis, we transformed response length, review length, a reviewer’s total number of reviews, a reviewer’s total number of images, a reviewer’s total earned helpfulness votes, room prices, and ages of the reviews into natural logarithm (ln) values. We assigned values (from 1 to 3) for the three response voices (i.e., defensive, formalistic, and accommodative) according to the level of empathy, which mainly refers to the sincerity of the problem acknowledgment and the intention to undertake further corrective action. The analysis results are shown in Table 4. Model 0 in Table 4 only shows the effect of control variables, whereas Model 1 includes the independent variables, namely, response length and voice. In addition, Model 2 analyzes the interactional effects of review and response qualities.

Table 4.

The relationship between B&B’s response and helpfulness votes.

According to Model 1, the relationships between response length, voice, and helpfulness votes are significant (0.078, p < 0.05, 0.102, p < 0.01); thus, H1 and H2 are supported. When considering the interactions between response and review qualities, the results are somehow different from our assumptions. As shown in Model 2 of Table 4, the relationship between response length and perceived helpfulness is strong in long or image-embedded reviews; thus, H3a and H3b are supported. However, the empathetic response voice is necessary when responding to short or long reviews, with or without images; thus, H4a and H4b are not supported.

3.3. Study 3: Additional Analyses on Response Length Based on Cognitive Load Theory (CLT)

As shown in Table 4, the relationship between response length and helpfulness votes (see Model 1) is not as strong as the relationship between the response voice and helpfulness. Moreover, when considering the interactions between response and review qualities, the relationship between response length and helpfulness votes is not significant. According to CLT, the inappropriate presentation of materials or information overload can reduce online search performance [78,79]. Long responses contain considerable information; however, readers could be unwilling to read overly long responses. We propose the following hypothesis to further check the relationship between response length and helpfulness votes:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

An inverted-U curve relationship exists between response length and helpfulness votes.

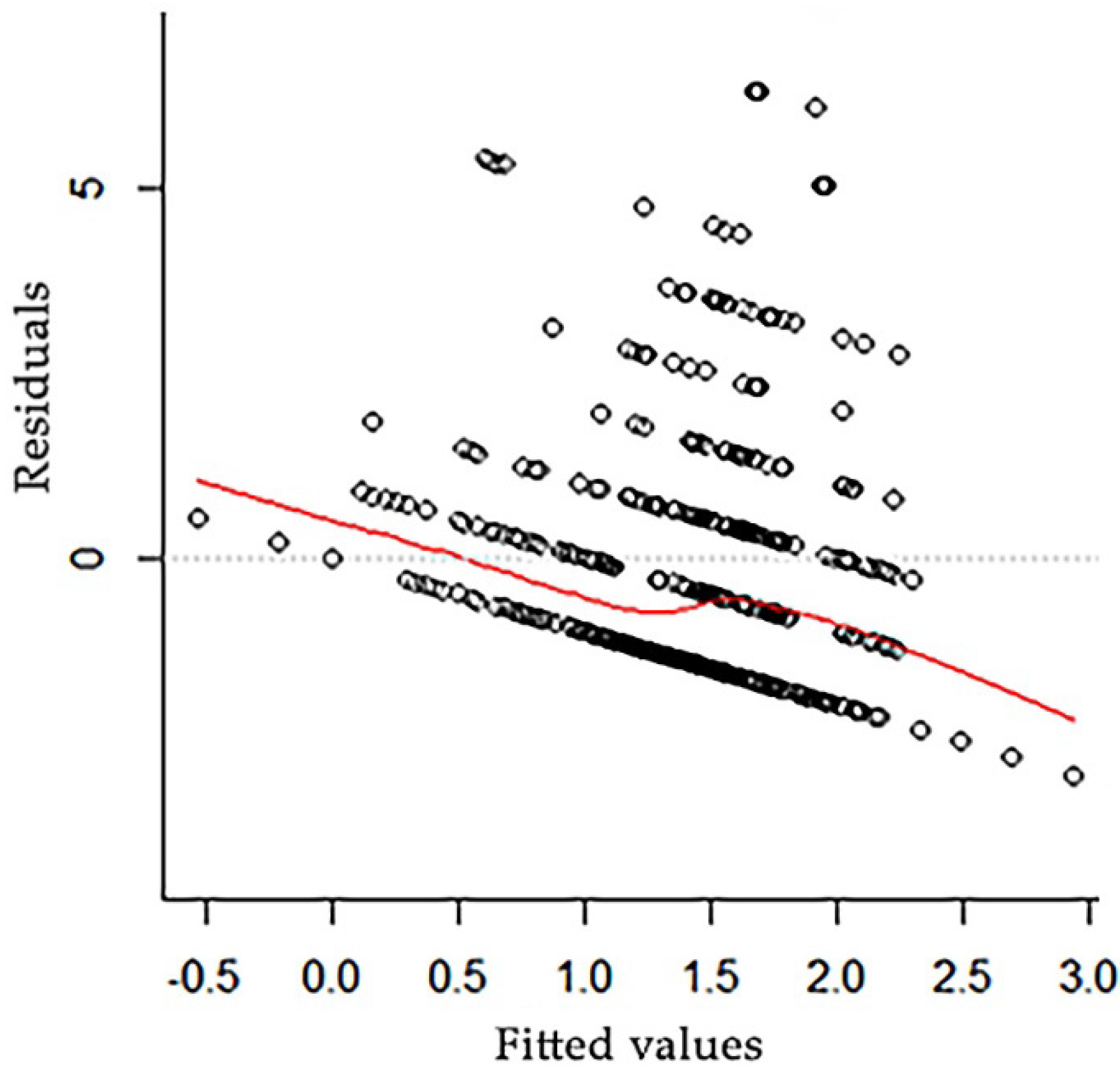

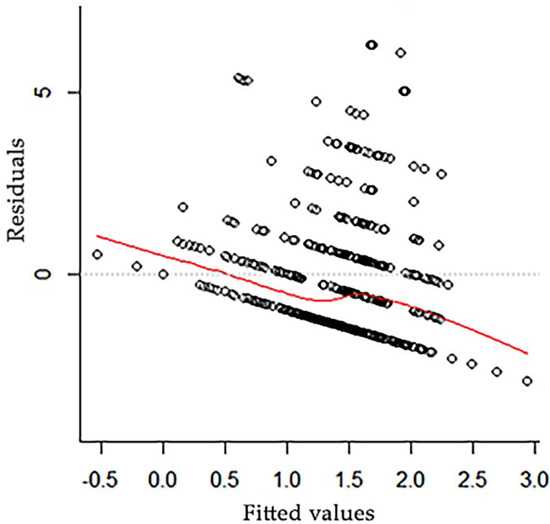

The “S” curve in the plot of residuals vs. fitted values, shown in Figure 1, indicates that the dependent variable (helpfulness votes) and the independent variable (response length) are not linearly related. Given this, the square of the response length was added in Model 3 to test the above hypothesis. Table 5 shows the results.

Figure 1.

The plot of residuals vs. fitted values.

Table 5.

Rechecking the relationship between response length and helpfulness votes.

According to Model 3, the relationship between the square of the response length and helpfulness votes is negatively significant (−0.567, p < 0.01), whereas no observable variations for other relationships exist. Meanwhile, the F value change is significant (6.814, p < 0.01); thus, our assumption of an inverted-U curve relationship in H5 is supported.

4. Discussions

By considering the empathy of responses in Study 1 and by referring to the response strategies proposed by Lui et al. [30], we generate three types of voices, namely defensive, formalistic, and accommodative. The different voices reflect the different B&Bs’ attitudes to consumer complaints and approaches in managing online reputation.

According to the results of Study 2, response length has a relationship with prospective consumers’ perceived helpfulness to some extent. This result somehow differs from the argument that long responses do not help in increasing helpfulness votes [27]. Considering the relatively low coefficient of response length, this research conducts additional analyses based on CLT. The result shows that the relationship between response length and perceived helpfulness presents an inverted-U curve. This result indicates that sufficiently long responses are informative and can help prospective consumers understand services; however, overly long responses are less effective. Response voice is verified to have a significant relationship with helpfulness votes, which is consistent with the statement that an accommodative response with empathy to negative reviews can improve consumers’ perceptions of services and help increase sales revenues [10,64]. Moreover, interactive effects exist between response length and review quality (including review length and review image), which indicate the necessity to include paraphrased statements to long negative reviews with embedded images [10]. Meanwhile, the empathetic voice is always effective regardless of how long a review is and whether or not images are included in the negative reviews.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

This research complements studies on eWOM management by exploring specific practices in the SE. The findings present the following theoretical implications. First, this research emphasizes the necessity to equip service providers with skills to respond to consumers’ complaints, as service personnel in the SE are informal and based on nonprofessional markets, such as privately-owned B&Bs.

Second, response length and voice are adopted as measures to evaluate the quality of response content. This research initially proposes and verifies the inverted-U curve relationship between response length and consumers’ perceived helpfulness based on CLT. This result, to a certain extent, supported the findings of Li et al. [27]. On the basis of the result of an empirical analysis, Li et al. [27] suggested that undue lengthy response poses cognitive overload and induces greater equivocality in prospective consumers’ information processing. The finding of this research suggests that an adequate long response conveys more information than a short response and has a positive effect on prospective consumers’ perceived helpfulness, but this effect will decrease if the response is prolonged. This finding provides a new perspective and a critical implication for studying online reviews and managerial responses. Prior studies have proposed several approaches to categorize the managers’ response strategy [12,30,31,64]. The present study learned from them and proposed a more reasonable and comprehensive categorizing method that identified three main categories and eight subcategories. In addition, the research results indicate that an accommodative voice is more helpful than other voices, thus illustrating the importance of the empathetic statements in response. This finding provides a theoretical basis for future research in this field.

Third, this research unveils the interactive effect between consumers’ reviews and businesses’ responses. Specifically, response length works with review length and images to influence prospective consumers’ perceptions of helpfulness, suggesting that we should adopt a comprehensive perspective that synchronously considers the argument quality of online reviews when studying managerial responses.

4.2. Practical Implications

This research generates several valuable insights for SE platforms and service providers, such as B&B hosts.

Active responses to online complaints can improve consumer satisfaction as well as perception of services. Therefore, SE platforms should encourage service providers to adopt the reputation system of the platforms. Considering the inverted-U shaped relationship between response length and its effectiveness, platforms can set an upper limit of the response length. For B&B hosts, proper expression of confession or correcting intention is necessary, but they should leverage the effect of response length on consumers’ perceived helpfulness and note that overly prolonged response should be avoided as it hinders consumers’ content processing. An empathetic statement in response is more effective than those without. When responding to consumers’ online complaints, the service provider must adopt an accommodative voice encompassing sincere apology, confession, promise for corrective action, or proper compensation. Specifically, when consumers’ complaints are caused by factors controllable by the service provider (e.g., breakfast without considering special groups, such as vegetarian), a confession and promise for further action should lead to higher consumer trust toward the service provider, whereas an excuse or a superficial apology does not help. However, a considerable amount of defensive and formalistic responses was found, when the contents of B&B responses were analyzed. Thus, platforms should develop training or instructions for service providers who are mainly from the informal sector to manage eWOM. Moreover, platforms should carry out reward schemes to commend service providers that do well in effectively managing consumer complaints to enhance the sustainable development of platforms and service providers.

Service providers, such as B&B hosts, should recognize that responses to online reviews are more telling than the reviews themselves because they show consumers how much businesses care about them. When responding to consumer complaints, service providers should consider the consumers’ positions and implement empathetic and thoughtful strategies to communicate with them rather than defending or denying their own failures. Service providers should also be skillful in evaluating consumers’ negative reviews and in expressing empathetic and properly paraphrased statements rather than giving excuses. Considering cognitive load, service providers should avoid long-winded statements despite the informativeness of long responses. Thus, to pursue sustainable performance and development, service providers in the SE should persistently improve their abilities and skills to manage online eWOM, actively listen to consumers, and sincerely respond to consumer complaints.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This research considers service providers’ responses to negative online reviews as a crucial factor that affects business reputation and sustainable performance in the SE. The ELM and IJT are adopted as the basis to emphasize the importance of managerial responses to negative eWOM. Response length and voice are examined to have differing relationships with consumers’ perceptions of services and helpfulness of online reviews. Specifically, response length presents an inverted-U curve relationship with helpfulness votes, as well as interactive effects with review quality. However, the empathic voice is verified to have a positive effect on consumers’ perceptions.

A few limitations exist despite the findings and implications of this research. First, although we assign values for three types of voices based on the level of empathy, reflecting the exact emotions of service providers is difficult. Thus, we should try to use sentiment analysis methods in future studies to analyze response contents. We sample reviews posted before 1 October, 2017 to ensure that the reviews and responses are sufficiently exposed to consumers. However, B&B reviews on Ctrip.com for that period are scarce, which led to a relatively limited sample size. Second, we coded each response into a certain category based on the principle of proximity. Future studies must consider if a response contains multiple voices. Furthermore, this research only analyzes the relationship between responses and helpfulness votes rather than examining the effect of managerial responses for future performance. It would be worthwhile to explore dynamic influencing mechanisms in future studies by examining the effect of responses(t) on sales(t+1), total reviews(t+1), and total helpfulness votes(t+1). Last, some neuroscience tools have been adopted to observe the consumers’ e-commerce website browsing behavior [80]. Such tools provide a new approach to acquire additional objective data about how consumers read online reviews and managerial responses.

Author Contributions

All the co-authors have contributed substantially and uniquely to the work reported. W.L. contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, and writing—original draft; R.J. contributed to formal analysis and methodology; C.N. contribute to methodology and validation; K.R. contributed to conceptualization, supervision, and review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (grant number NS2017056).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Godes, D.; Mayzlin, D. Using online conversations to study word-of-mouth communication. Market. Sci. 2004, 23, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Youn, S. Electronic word of mouth: How eWOM platforms influence consumer product judgement. Int. J. Advert. 2009, 28, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z. The business value of online consumer reviews and management response to hotel performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, D.; Han, I. The effect of negative online consumer reviews on product attitude: An information processing view. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Allen, J.P. Responding to online reviews. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.A.; Mayzlin, D. The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. J. Market. Res. 2006, 43, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X. Impact of online consumer reviews on sales: The moderating role of product and consumer characteristics. J. Market. 2010, 74, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, D.; Meyers-Levy, J. The influence of message framing and issue involvement. J. Market. 1990, 27, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. The influence of message framing and issue involvement on promoting abandoned animals adoption behaviours. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 82, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Lim, Y.; Magnini, V.P. Factors affecting customer satisfaction in responses to negative online hotel reviews. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2015, 56, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Law, R.; Gu, B. The impact of online user reviews on hotel room sales. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B.A.; So, K.K.F.; Bradley, G.L. Responding to negative online reviews: The effects of hotel responses on customer inferences of trust and concern. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.E.; Duan, W.; Boo, S. An analysis of one-star online reviews and responses in the Washington, D.C. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.E.K.; Mattila, A.S.; Baloglu, S. Effects of gender and expertise on consumers’ motivation to read online hotel reviews. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2011, 52, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noort, G.; Willemsen, L.M. Online damage control: The effects of proactive versus reactive webcare interventions in consumer-generated and brand-generated platforms. J. Interact. Market. 2012, 26, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S.K.; Lehner, M. Defining the sharing economy for sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Rong, K.; Luo, M.; Wang, Y.; Mangalagiu, D.; Thornton, T.F. Value co-creation for sustainable consumption and production in the sharing economy in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscicelli, L.; Cooper, T.; Fisher, T. The role of values in collaborative consumption: Insights from a product-service system for lending and borrowing in the UK. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Tech. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C.; Öberg, C.; Sandström, C. How sustainable is the sharing economy? On the sustainability connotations of sharing economy platforms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battino, S.; Lampreu, S. The role of the sharing economy for a sustainable and innovative development of rural areas: A case study in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2019, 11, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, G.; Jia, F.; Sun, H. Sharing economy–based service triads: Towards an integrated framework and a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laamanen, M.; Wahlen, S.; Lorek, S. A moral householding perspective on the sharing economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, R.; Viglia, G.; Furlan, R. Who am I? How compelling self-storytelling builds digital personal reputation. J. Interact. Market. 2016, 35, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiang, D.; Yang, Z.; Ma, S. Unraveling customer sustainable consumption behaviors in sharing economy: A socio-economic approach based on social exchange theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cui, G.; Peng, L. The signaling effect of management response in engaging customers: A study of the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Ye, Q. First step in social media—Measuring the influence of online management responses on customer satisfaction. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2011, 23, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Singh, A.; Lee, S.K. Effects of managerial response on consumer eWOM and hotel performance: Evidence from TripAdvisor. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2013–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, T.; Bartosiak, M.; Piccoli, G.; Sadhya, V. Online review response strategy and its effects on competitive performance. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Song, S. An empirical investigation of electronic word-of-mouth: Informational motive and corporate response strategy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyódi, K. Airbnb in European cities: Business as usual or true sharing economy? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacile, T.J.; Wolter, J.S.; Allen, A.M.; Xu, P. The effects of online incivility and consumer-to-consumer interactional justice on complainants, observers, and service providers during social media service recovery. J. Interact. Market. 2018, 44, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Fürst, A. How organizational complaint handling drives customer loyalty: An analysis of the mechanistic and the organic approach. J. Market. 2005, 69, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.A.; Yaseen, A.; Wasaya, A. Drivers of customer loyalty and word of mouth intentions moderating role of interactional justice. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 2018, 27, 877–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, D.; Head, M.; Lim, E.; Stibe, A. Using the elaboration likelihood model to examine online persuasion through website design. Inf. Manag. Amster. 2018, 55, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Lee, J.; Han, I. The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2007, 11, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, J.Q. Born unequal: A study of the helpfulness of user-generated product reviews. J. Retail. 2011, 87, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Law, R.; Rong, J.; Li, G.; Hall, J. Analyzing changes in hotel customers’ expectations by trip mode. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiei, B.; Dospinescu, N. Electronic Word-of-Mouth for online retailers: Predictors of volume and valence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Vásquez, C. Hotels’ responses to online reviews: Managing consumer dissatisfaction. Discourse Context Media 2014, 6, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z.K.; Zhao, S.J.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. Examining the influence of online reviews on consumers’ decision-making: A heuristic–systematic model. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 67, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y. How credible are online product reviews? The effects of self-generated and system-generated cues on source credibility evaluation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.Y.; Luo, C.; Sia, C.L.; Chen, H.P. Credibility of electronic word-of-mouth: Informational and normative determinants of on-line consumer recommendations. Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2009, 13, 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O.; Rabjohn, N. The impact of electronic word-of-mouth—The adoption of online opinions in online customer communities. Internet Res. 2008, 18, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Xia, W.D. A longitudinal experimental study on the interaction effects of persuasion quality, user training, and first-hand use on user perceptions of new information technology. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Park, S. What makes a useful online review? Implication for travel product websites. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J.A.; Boninger, D.S.; Chuang, Y.C.; Berent, M.K. Attitude strength: One construct or many related constructs? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 1132–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemsen, L.M.; Neijens, P.C.; Bronner, F.; de Ridder, J.A. “Highly Recommended!” The content characteristics and perceived usefulness of online consumer reviews. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2011, 17, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfiatis, N.; García-Bariocanal, E.; Sánchez-Alonso, S. 2012 Evaluating content quality and helpfulness of online product reviews: The interplay of review helpfulness vs. review content. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.H.; Chen, K.; Yen, D.C.; Tran, T.P. A study of factors that contribute to online review helpfulness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Lafferty, B.A.; Newell, S.J. The impact of corporate credibility and celebrity credibility on consumer reaction to advertisements and brands. J. Advert. 2000, 29, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidwell, L.C.; Walther, J.B. Computer-mediated communication effects on disclosure, impressions, and interpersonal evaluations: Getting to know one another a bit at a time. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 317–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Lerman, D. Why are you telling me this? An examination into negative consumer reviews on the Web. J. Interact. Market. 2007, 21, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. Source expertise, time of source identification, and involvement in persuasion: An elaborative processing perspective. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. The effects of expert and consumer endorsements on audience response. J. Advert. Res. 2005, 45, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.M.; Lurie, N.H.; Macinnis, D.J. Listening to strangers: Whose responses are valuable, how valuable are they, and why? J. Market. Res. 2008, 45, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racherla, P.; Friske, W. Perceived ‘usefulness’ of online consumer reviews: An exploratory investigation across three services categories. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, C.; Ghose, A.; Wiesenfeld, B. Examining the relationship between reviews and sales: The role of reviewer identity disclosure in electronic markets. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, B.J.; Marshall, J.; Laraki, O.; Osipovich, A.; Varma, C.; Fang, N.; Paul, J.; Rangnekar, A.; Shon, J.; Swani, P.; et al. What makes web sites credible? A report on a large quantitative study. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Washington, DC, USA, 31 March–5 April 2001; Volume 3, pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lui, T.; Piccoli, G. The effect of a multichannel customer service system on customer service and financial performance. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, V. The becoming of user-generated reviews: Looking at the past to understand the future of managing reputation in the travel sector. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, S.; Brunner, C.B. Negative online consumer reviews: Effects of different responses. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cui, G.; Peng, L. Tailoring management response to negative reviews: The effectiveness of accommodative versus defensive responses. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the Internet? J. Int. Market. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P.; Royzman, E.B. Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 5, 296–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Rodgers, S.; Kim, M. Effects of valence and extremity of ewom on attitude toward the brand and website. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2009, 31, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N.L.; Guillet, B.D. Investigation of social media marketing: How does the hotel industry in hong kong perform in marketing on social media websites? J. Travel Tour. Market. 2011, 28, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, T.; Castaño, R. How should managers respond? Exploring the effects of different responses to negative online reviews. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Market. 2013, 3, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, O.; Krasnova, H.; Shavanova, T.; Fuhrer, A.; Buxmann, P. Impression management in the sharing economy: Understanding the effect of response strategy to negative reviews. Die Unternehm. 2016, 70, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K. Audience-oriented approach to crisis communication: A study of Hong Kong consumers’ evaluation of an organizational crisis. Commun. Res. 2004, 31, 600–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B.; Gardial, S.F. Know Your Customer: New Approaches to Understanding Customer Value and Satisfaction; Blackwell Business: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W. Reliability of content analysis: The case of nominal scale coding. Public Opin. Q. 1955, 17, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Snyder-Duch, J.; Bracken, C.C. Content analysis in mass communication research: An assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otondo, R.F.; Van Scotter, J.R.; Allen, D.G.; Palvia, P. The complexity of richness: Media, message, and communication outcomes. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiei, B.; Dospinescu, N. A model of the relationships between the Big Five personality traits and the motivations to deliver word-of-mouth online. Psihologija 2018, 51, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ji, R. Do hotel responses matter? A comprehensive perspective on investigating online reviews. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 32, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollender, N.; Hofmann, C.; Deneke, M.; Schmitz, B. Integrating cognitive load theory and concepts of human–computer interaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xie, C. Using time pressure and note-taking to prevent digital distraction behavior and enhance online search performance: Perspectives from the load theory of attention and cognitive control. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 88, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dospinescu, O.; Percă-Robu, A.E. The analysis of e-commerce sites with Eye-Tracking technologies. Brain 2017, 8, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).