Structured Collaboration Across a Transformative Knowledge Network—Learning Across Disciplines, Cultures and Contexts?

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Background

2. Transdisciplinary Research and Transformations to Sustainability

2.1. Insights from the Literature

- Be inclusive in the diversity of participants, the power accorded to them and the processes and objectives of co-production. Ensure that the institutions that enable co-production attend carefully to the credibility, legitimacy and accountability this entails.

- Acknowledge that co-production is a process of reconfiguring science and its social authority. Such processes require participants to be reflexive about the inherently political nature of producing knowledge in the service of changing social order at local to global scales.

- Recognize that public engagement, deliberation and debate will shape the content and relevance of knowledge and its ability to help construct and empower institutions to “facilitate sustainability” [14]

2.2. The Pathways Network’s Approach

- -

- The future of seeds (and agriculture) in Argentina/South America hub—Centre for Research on Transformation (CENIT), Buenos Aires, Argentina

- -

- Transformations to sustainable food systems in Brighton and Hove/Europe hub—STEPS Centre, University of Sussex, UK and Stockholm Resilience Centre, Sweden

- -

- Low carbon energy transitions that meet the needs of the poor/Africa Sustainability Hub—African Centre for Technology Studies, Nairobi, Kenya

- -

- China’s green transformations/China Hub—Beijing Normal University School of Social Development and Public Policy, China

- -

- The urban system of water and waste management in Gurgaon, India/South Asia hub—Transdisciplinary Research Cluster on Sustainability Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi India

- -

- Water governance challenges, Mexico City/North America hub—Arizona State University, USA and National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

3. Structured Design to Allow for Co-Learning and Exchange

4. Anchors as a Focus for Cross-Learning and Negotiation

4.1. Theoretical Anchors

- -

- Systems—“particular configurations of dynamic interacting social, technological and environmental elements” [31]. The focus on systemic transformation underpinned the design of the project. This included a definition of the system (including explicit attention to how the system was framed) in the original co-design phase and a consideration of how the system needed to change to overcome the sustainability problem that motivated the research.

- -

- Framings—“the different ways of understanding or representing a social, technological or natural system and its relevant environment. Among other aspects, this includes the ways system elements are bounded, characterized and prioritized and meanings and normative values attached to each” [31]. Building on Goffman’s [32] seminal work, the notion of framing has a long history in policy studies [33,34,35] and has been incorporated into the pathways approach. The co-design workshops and concept notes that emerged from them recognised different system framings and their fundamental link to debates and challenges associated with sustainability. Whilst notions of “reframing” such debates have been applied to the pathways approach in previous studies (see References [36,37]), the current project offered significant opportunities to develop this area of thinking.

- -

- Pathways—“the particular directions in which interacting social, technological and environmental systems co-evolve over time” [31]. The concept notes that had emerged from co-design workshops identified dominant and alternative pathways but adopted different lenses through which these were characterised in each context. At the same time, the pathways approach (and the notion of pathways) played a different role (and a more-or-less important role) in each case. Some hubs conceived of pathways as open-ended, with the T-Lab process relatively agnostic to the ultimate direction pursued as long as it emerged from the empowerment of participants and their normative sustainability goals (North America hub, European hub). In other cases, the ambition was to alter current dominant trajectories by introducing a specific, compelling alternative technological and institutional pathway (Latin America hub). In the South Asia Hub, the approach was to challenge the regime of neo-liberal urban planning and governance and form a collective agency of the mobilised publics to promote the coproduction of knowledge and co-design of alternative solutions. In some cases (e.g., China hub) gender played a more central role to the work, whilst others (Africa hub) engaged more with issues of poverty and environmental sustainability. Taken together, these approaches to innovating around the notion of ‘pathways’ offered potential insights into transformative pathways to sustainability.

4.2. Methodological Anchors

5. Results, Findings and Emerging Insights

5.1. Accommodating Theoretical Diversity

5.2. Methodological Differences and Normative Commitments

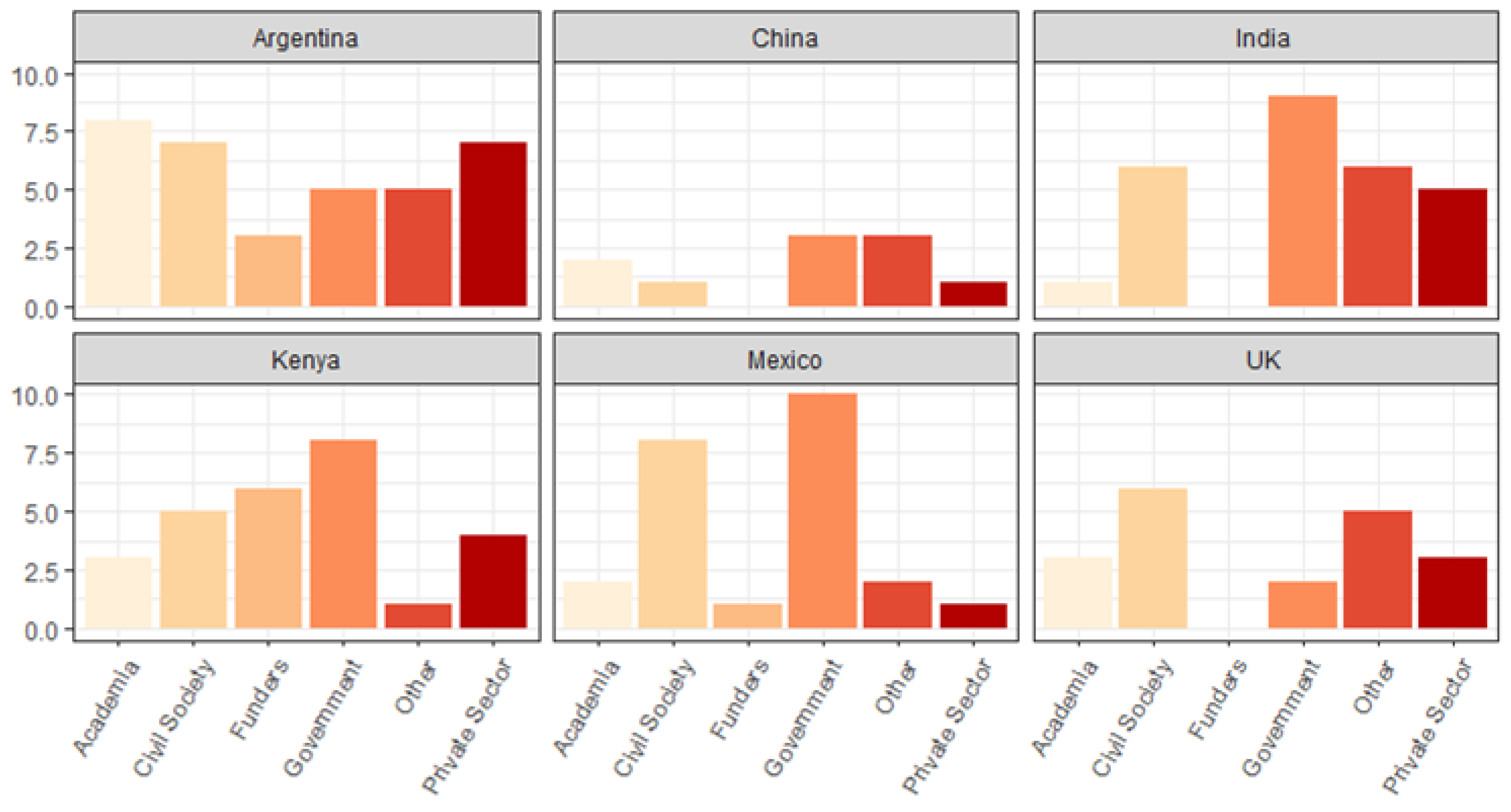

5.3. Learning from Diverse Experiences with Multiple Variables

5.4. Transformation, Emergence and Evaluation

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNGSDR. United Nations Global Sustainable Development Report 2019: The Future Is Now—Science for Achieving Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Future Earth. Future Earth Annual Report 2018–2019. Available online: https://futureearth.org/publications/annual-reports/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Ely, A.; Marin, A. Learning about ‘Engaged Excellence’ across a Transformative Knowledge Network. IDS Bull. 2017, 47, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Research Council. Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, W.C. Sustainability Science: An Emerging Interdisciplinary Frontier; The Rachel Carson Distinguished Lecture Series; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch Hadorn, G.H.; Pohl, C. Principles for Designing Transdisciplinary Research; Oekom Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch Hadorn, G.H.; Hoffmann-Riem, H.; Biber-Klemm, S.; Grossenbacher-Mansuy, W.; Joye, D.; Pohl, C.; Wiesmann, U.; Zemp, E. (Eds.) Handbook of Transdisciplinary Research. Proposed by the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hackmann, H.; St Clair, A.L. Transformative Cornerstones of Social Science Research for Global Change Report of the International Social Science Council; International Social Science Council: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mauser, W.; Klepper, G.; Rice, M.; Schmalzbauer, B.S.; Hackmann, H.; Leemans, R.; Moore, H. Transdisciplinary global change research: The co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 2013, 5, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brandt, P.; Ernst, A.; Gralla, F.; Luederitz, C.; Lang, D.J.; Newig, J.; Reinert, F.; Abson, D.J.; von Wehrden, H.A. Review of transdisciplinary research in sustainability science. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 92, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson Klein, J. Sustainability and Collaboration: Crossdisciplinary and Cross-Sector Horizons. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norström, A.V.; Cvitanovic, C.; Löf, M.F.; West, S.; Wyborn, C.; Balvanera, P.; Bednarek, A.T.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; De Bremond, A.; et al. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.A.; Wyborn, C. Co-production in global sustainability: Histories and theories. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018. corrected proof published online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Future Earth. Future Earth 2025 Vision; International Council for Science (ICSU): Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Scales, polycentricity and incentives: Designing complexity to govern complexity. In Protection of Global Biodiversity: Converging Strategies; Guruswamy, L.D., McNeely, J.A., Eds.; Duke University Press: Raleigh, NC, USA, 1998; pp. 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff, S. (Ed.) States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and Social Order; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, A.W.; Wickson, F.; Carew, A.L. Transdisciplinary: Context, contradictions and capacity. Futures 2008, 40, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S. Admitting uncertainty, transforming engagement: Towards caring practices for sustainability beyond climate change. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 1571–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pathways Network. T-Labs: A Practical Guide—Using Transformation Labs (T-Labs) for Innovation in Social-Ecological Systems; STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schäpke, N.; Stelzer, F.; Caniglia, G.; Bergmann, M.; Wanner, M.; Singer-Brodowski, M.; Loorbach, D.; Olsson, P.; Baedeker, C.; Lang, D.J. Jointly experimenting for transformation? Shaping real-world laboratories by comparing them. GAIA 2018, 27, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, A.; Ely, A.; van Zwanenberg, P. Co-design with aligned and non-aligned knowledge partners: Implications for research and coproduction of sustainable food systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 2016, 20, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method and Practice; Addison-Wesley: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zwanenberg, P.; Marin, A.; Ely, A. How Do We End the Dominance of Rich Countries Over Sustainability Science? STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Star, S.L.; Griesemer, J.R. Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–1939. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1989, 19, 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zwanenberg, P.; Ely, A.; Smith, A. Regulating Technology: International Harmonization and Local Realities; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fressoli, M.; Arond, E.; Dinesh Abrol, D.; Smith, A.; Ely, A.; Dias, R. When grassroots innovation movements encounter mainstream institutions: Implications for models of inclusive innovation. Innov. Dev. 2014, 4, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leach, M. (Ed.) Re-framing Resilience: A Symposium Report: STEPS Working Paper 13; STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- STEPS Centre. Innovation, Sustainability, Development: A New Manifesto; STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, M.; Rockström, J.; Raskin, P.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A.C.; Smith, A.; Thompson, J.; Millstone, E.; Ely, A.; Arond, E.; et al. Transforming innovation for sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 1708–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leach, M.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A.C. Dynamic Sustainabilities: Technology, Environment and Social Justice; Routledge/Earthscan: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience; Northeastern University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.; Rein, M. Frame Reflection: Towards the Resolution of Intractable Policy Issues; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Levidow, L.; Murphy, J. Reframing regulatory science: Trans-Atlantic conflicts over GM crops. Cahiers D’économie et Sociologie Rurales 2003, 68–69, 48–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ely, A.; Stirling, A.; Wendler, F.; Vos, E. The process of framing. In Food Safety Governance: Integrating Science, Precaution and Public Involvement; Dreyer, M., Renn, O., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchi, B.; Ely, A. Framing and Reframing Sustainable Bioenergy Pathways: The Case of Emilia Romagna: STEPS Working Paper 88; STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, F.; Randhawa, P.; Kushwaha, P.; Desai, P. Pathways for sustainable urban waste management and reduced environmental health risks in India: Winners, losers and alternatives to Waste to Energy in Delhi. Front. Sustain. Cities. (under review).

- Westley, F.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Homer-Dixon, T.; Vredenburg, H.; Loorbach, D.; Thompson, J.; Nilsson, M.; Lambin, E.; Sendzimir, J.; et al. Tipping toward sustainability: Emerging pathways of transformation. AMBIO 2011, 40, 762–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schot, J.; Kivimaa, P.; Torrens, J. Transforming Experimentation: Experimental Policy Engagements and Their Transformative Outcomes; Transformative Innovation Policy Consortium: Brighton, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.tipconsortium.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Transforming-Experimentation.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Nevens, F.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gorissen, L.; Loorbach, D. Urban transition labs: Co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z. The Social Labs Revolution; Berrett–Koehler Publisher: Oakland, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Westley, F.; Laban, S. (Eds.) Social Innovation Lab Guide; Waterloo Institute for Social Innovation and Resilience: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B.; Ståhlbröst, A. Living lab: An open and citizen centric approach for innovation. IJIRD 2009, 1, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keyson, D.V.; Guerra-Santin, O.; Lockton, D. (Eds.) Living Labs: Design and Assessment of Sustainable Living; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, F.; Schäpke, N.; Stelzer, F.; Bergmann, M.; Lang, D.J. BaWü-labs on their way: Progress of real-world laboratories in Baden-Württemberg. GAIA 2016, 25, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douthwaite, B.; Alvarez, S.; Cook, S.; Davies, R.; George, P.; Howell, J.; MacKay, R.; Rubiano, J. Participatory impact pathways analysis: A practical application of program theory in research for development. Can. J. Program Eval. 2007, 22, 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ely, A.; Oxley, N. STEPS Centre Research: Our Approach to Impact, STEPS Working Paper 60; STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I.; Stirling, A.; Abrol, D.; Atela, J.; Charli-Joseph, L.; Eakin, H.; Ely, A.; Olsson, P.; Pereira, L.; Priya, R.; et al. Transformations to Sustainability: STEPS Working Paper 104; STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abson, D.J.; Fischer, J.; Leventon, J.; Newig, J.; Schomerus, T.; Vilsmaier, U.; von Wehrden, H.; Abernethy, P.; Ives, C.D.; Jager, N.W.; et al. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. AMBIO 2017, 46, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, K. Global environmental change II: From adaptation to deliberate transformation. Prog. Hum, Geogr. 2012, 36, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Galaz, V.; Boonstra, W.J. Sustainability transformations: A resilience perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pelling, M. Transformation: A renewed window on development responsibility for risk management. J. Extrem. Events 2014, 1, 1402003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelling, M.; O’Brien, K.; Matyas, D. Adaptation and transformation. Clim. Chang. 2015, 133, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westley, F.R.; Tjornbo, O.; Schultz, L.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Crona, B.; Bodin, Ö. A theory of transformative agency in linked social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, R.M.; Fazey, I.; Smith, M.S.; Park, S.E.; Eakin, H.C.; Van Garderen, E.A.; Campbell, B. Reconceptualising adaptation to climate change as part of pathways of change and response. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haasnoot, M.; Kwakkel, J.H.; Walker, W.E.; ter Maat, J. Dynamic adaptive policy pathways: A method for crafting robust decisions for a deeply uncertain world. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scoones, I.; Leach, M.; Newell, P. (Eds.) The Politics of Green Transformations; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A.; Berkhout, F. The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1491–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzen, B.; Geels, F.W.; Green, K. (Eds.) System Innovation and the Transition to Sustainability: Theory, Evidence and Policy; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ockwell, D.; Atela, J.; Mbeva, K.; Chengo, V.; Byrne, R.; Durrant, R.; Kasprowicz, V.; Ely, A. Can pay-as-you-go, digitally enabled business models support sustainability transformations in developing countries? Outstanding questions and a theoretical basis for future research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chulin, J.; Yang, L.; Jian, X.; Ely, A. Research on ‘Green Unemployed Group’ from the perspective of resilience. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2018, 347, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Tyfield, D.; Ely, A.; Geall, S. Low carbon innovation in China: From overlooked opportunities and challenges to transitions in power relations and practices. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmitz, H. Who drives climate-relevant policies in the rising powers? New Political Econ. 2017, 22, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, L.M.; Karpouzoglou, T.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Olsson, P. Designing transformative spaces for sustainability in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, L.M.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Hebinck, A.; Charli-Joseph, L.; Drimie, S.; Dyer, M.; Eakin, H.; Galafassi, D.; Karpouzoglou, T.; Marshall, F.; et al. Transformative spaces in the making: Key lessons from nine cases in the Global South. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 15, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, F.; Van Zwanenberg, P.; Charli-Joseph, L.; Ely, A.; Eakin, H.; Marin, A.; Priya, R. Chapter 8: Reframing sustainability challenges. In Transformative Pathways to Sustainability: Learning Across Disciplines, Cultures and Contexts; Ely, A., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Douthwaite, B.; Apgar, J.M.; Schwarz, A.-M.; Attwood, S.; Sellamuttu, S.S.; Clayton, T. A new professionalism for agricultural research for development. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2017, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, H.; Patsalides, M. Complexity-Aware Monitoring. Discussion Note, Monitoring and Evaluation Series; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, I. Review of the Use of Theory of Change in International Development; DFID: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.L.; Olsson, P.; Nilsson, W.; Rose, L.; Westley, F.R. Navigating emergence and system reflexivity as key transformative capacities. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberlack, C.; Breu, T.; Giger, M.; Harari, N.; Herweg, K.; Mathez-Stiefel, S.-L.; Messerli, P.; Moser, S.; Ott, C.; Providoli, I.; et al. Theories of change in sustainability science: Understanding how change happens. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2019, 28, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Giger, M.; Harari, N.; Moser, S.; Oberlack, C.; Providoli, I.; Schmid, L.; Tribaldos, T.; Zimmermann, A. Transdisciplinary co-production of knowledge and sustainability transformations: Three generic mechanisms of impact generation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 102, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Berkes, F. Adaptive co-management for building resilience in social–ecological systems. Environ. Manag. 2004, 34, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Challenge to Undertaking Transdisciplinary Approaches to Sustainability Science | Finding of Review [11] |

|---|---|

| Coherent Framing | Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science is increasing but under diverse terms |

| Integration of Methods | Method sets used are independent of process phases and knowledge types |

| Research Process and Knowledge Production. | There is a gap between ‘best practice’ transdisciplinary research as advocated and transdisciplinary research as published in scientific journals |

| Practitioners’ Engagement | Knowledge is interchanged, yet empowerment is rare |

| Generating Impact | Generating transdisciplinary research with high-scientific impact remains challenging |

| Month | Event | Collaborative Developments |

|---|---|---|

| September 2014–March 2015 | Co-design workshops in each hub produce case-specific concept notes, feeding into TKN proposal | Sharing of contextual background, “problem space” and proposed transdisciplinary research projects |

| April 2016 | Inception workshop including adapted PIPA processes, T-Lab discussions and strategic planning | Initial sharing of ideas around Transformation Labs, ‘Pathways’ methods and hub case studies |

| June 2016 | Baseline survey circulated for completion by all hub teams | |

| May 2016–August 2017 | First round of T-Lab workshops, including collaborative planning process (T-Lab format) and internal & external reporting1 | Sharing of initial research data, T-Lab design, implementation and learning, as well as future plans in each hub |

| July 2017 | Mid-point survey circulated for completion by all hub teams | |

| September 2017 | T-Lab training and reflection workshop, including identification of thematic insights | Identification of key themes for exploration: T-Labs, theories of change, framing, innovation |

| October 2017–October 2018 | Second round of T-Lab workshops, including internal & external reporting 1 | Sharing of further data, T-Lab experiences (positive and negative) and future plans in each hub |

| October 2018 | Final workshop, including further discussions around theory, research and action | Time-constrained discussions of theoretical and methodological differences, as well as emerging insights. |

| November 2018 | Final survey circulated for completion by all hub teams | |

| October 2019 | Follow-up workshop, including reflection on lessons, planning for publications and future work. | Time-constrained discussion of insights around theoretical and methodological anchors, reframing, innovations etc. |

| Hub | General Objective of Project/Case Study | Underlying Theories of Transformation That Inform the Choice of Method |

|---|---|---|

| North America Hub (Mexico) | To design and implement a process known as “transformation laboratories” with the aim of identifying, mobilizing and activating individual and collective agency of actors involved in the social-ecological dynamics of the Xochimilco urban wetland. | Transformation is about bottom-up building of collective agency through reframing systems dynamics. Transformations to sustainability (e.g., [49,50,51,52,53]); Transformative agency (e.g., [38,54]); Pathways (e.g., [25,55,56]) |

| Europe Hub (UK) | To design and implement research and “transformation laboratories” with the aim of enhancing the supply of local, sustainably-produced food into Brighton & Hove (and drawing wider lessons for the UK’s agricultural transformations) | Transformation is influenced by changing cognitive, affective and political economic drivers that work across individuals, groups and systems. Pathways [31], politics of green transformations [57], governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions [58], transformative pathways [4]. |

| South America Hub (Argentina) | To design and implement “transformation laboratories” (T-Labs) with the aim of creating an experimental space in which coalitions of heterogenous actors can agree on a sustainability problem in the agricultural seed sector and develop and prototype possible solutions | Transformation involves experimentation with novel, more sustainable socio-technical practices and the development of alternative ‘path breaking’ socio-technical configurations [59,60]. |

| Africa Hub (Kenya) | To use the T-Lab approach to explore how Kenya can enable sustainable and equitable access to solar home systems for all via mobile-based payment systems, especially those who cannot participate in micro-financing schemes [61]. | The T-Lab involved different stakeholders (government, NGOs, Civil society, Private sector development partners, research and academia) who provided rich and diverse insights into what needs to be done or changed to enable equitable, sustainable access for all, to solar PV systems via mobile-based payment systems. |

| China Hub | This study engages in the social dimensions of green transformation in order to provide a more holistic picture of the transformations to sustainability [62]. | Transformations in China are driven by a number of actors [63,64]. The change agents are different stakeholders in transformation, including laid-off workers, former plant owners, local government officials, scholars, NGOs, etc |

| South Asia Hub (India) | To design and implement transformation labs as a process with the aim of promoting a collective strategy for intervention to bring together the mobilised publics specifically representing poor and marginalised along with middle classes to develop the collective practical understanding and build alliances for enabling their participation in planning and decision making processes of water and waste water management | Transformation is conceptualised as enabling the people as a whole specifically poor and marginalised to enhance their access to resources and capabilities for mobilisation of power to innovate and foster regime change that helps to create conditions for the realisation of ecologically and socially just development. |

| Hub | Method & Purpose/General Description | Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| North America Hub (Mexico) | Agency Network Analysis (ANA) Mixed method Describe the actor’s agency profile by identifying individual agency through collecting information about actors’ social network, the practices they share with the members of their social network, their representation of the social ecological system and the position they occupy in it. | Ego-nets; action-nets; cognitive maps |

| South Asia Hub (India) | Multi-stakeholder processes for the mobilised publics through the development of their Collective Practical Understanding (CPU) and actions Mixed Method Coproduction of knowledge, knowledge sharing, dialogues and engagement with institutions of planning and governance for demonstrating the possibilities of alternative pathways. Development of multi-stakeholder-knowledge-sharing platform enabling social mobilisation and awareness, including direct actions, participation and real-world experiments. Mapping of knowledge, values and institutions of mobilised publics and organising them for the creation of a multi-stakeholder platform for individual and collective actions. | Transects, public meetings & focus group discussion (FGD), multi-stakeholder consultations, community radio programmes, poster exhibitions, citizens science; citizens watch approaches & tools; Real world experiments |

| Europe Hub (UK) | Continuum’ methods, specifically Evaluation H Qualitative method Identify different actors’ positions and perspectives (especially at the extremes), foster discussion across them, identify challenges and opportunities and work towards solutions. Gather participants together to position themselves in relation to each other and to open up debate. It can be effective if participants represent different sectors, backgrounds or types of involvement in the issue being explored, particularly if these different stakeholders do not interact often. | Facilitated, participatory workshop |

| South America Hub (Argentina) | Q Methodology Mixed method Identify competing discourses about the nature of sustainability challenges, their drivers and their possible solutions in the seed sector and map areas of consensus and disagreement between different groups of stakeholders; Identify different actors’ perspectives, foster discussion across them, identify where alliances between different actors are possible and work towards solutions. | World café; open space technology |

| Africa Hub (Kenya) | Participatory Impact Pathways Analysis (PIPA) Qualitative method Identification of impact pathways to detect key stakeholders with interest and influence in policy, business and technology; to identify the various pathways for transformation; target what pathways (i.e., engagements, networks) could be engaged in the process so as to enhance uptake of the research outputs. | Participatory workshop |

| China Hub | Role play simulation Qualitative method All participants play different roles in response to a situation introduced by a facilitator. The situation can either be the one under discussion or another (fictional or real) situation where a similar problem is faced. The volunteers all stand on a starting line and the facilitator announces hypothetical policies or projects which will be implemented. Based on their roles, the volunteers take either a step forward (if they are to benefit from the policy), backward (if it will have negative impact on them) or stay still (if it will have no impact). At the end, participants discuss the differences between the winners and losers and how this exercise compares to their own experience. | Role play |

| What Worked? | What Didn’t Work? |

|---|---|

| Respect, learning from diversity across hubs | Time and resources were a constraint to interactions, reflection and learning |

| Inception workshop for getting to know each other made a good base—the culture and tone of the project set from the start | Theoretical and methodological exchanges were limited (different hubs approached methods very differently) |

| Friendships and networking | Technological challenges of virtual, de-centralised information exchange: all platforms problematic or limited |

| Autonomy in the hubs was appreciated (freedom to find what works for them) | Opportunities for follow-on funding have not been successful |

| Knowledge generation and the move from their research to action and impact | South-South interactions were not fully made use of |

| Having meetings at points throughout the project was great | Pairing hubs didn’t always work due to different approaches/lack of continuity of engagement/‘chemistry’ |

| Establishing global movement in sustainability, transformative research and action | |

| Legitimate input from the global South | Stakeholders in hubs expect continued support but resources are no longer available |

| Connecting the community beyond the limits of their own territories to bring in new learning | |

| Central synthesising of information was helpful to internal communications | Measuring impact because of a lack of clear definition of what impact is |

| Commitment from hubs despite challenges faced in their different contexts of work |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ely, A.; Marin, A.; Charli-Joseph, L.; Abrol, D.; Apgar, M.; Atela, J.; Ayre, B.; Byrne, R.; Choudhary, B.K.; Chengo, V.; et al. Structured Collaboration Across a Transformative Knowledge Network—Learning Across Disciplines, Cultures and Contexts? Sustainability 2020, 12, 2499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062499

Ely A, Marin A, Charli-Joseph L, Abrol D, Apgar M, Atela J, Ayre B, Byrne R, Choudhary BK, Chengo V, et al. Structured Collaboration Across a Transformative Knowledge Network—Learning Across Disciplines, Cultures and Contexts? Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062499

Chicago/Turabian StyleEly, Adrian, Anabel Marin, Lakshmi Charli-Joseph, Dinesh Abrol, Marina Apgar, Joanes Atela, Becky Ayre, Robert Byrne, Bikramaditya K. Choudhary, Victoria Chengo, and et al. 2020. "Structured Collaboration Across a Transformative Knowledge Network—Learning Across Disciplines, Cultures and Contexts?" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062499

APA StyleEly, A., Marin, A., Charli-Joseph, L., Abrol, D., Apgar, M., Atela, J., Ayre, B., Byrne, R., Choudhary, B. K., Chengo, V., Cremaschi, A., Davis, R., Desai, P., Eakin, H., Kushwaha, P., Marshall, F., Mbeva, K., Ndege, N., Ochieng, C., ... Yang, L. (2020). Structured Collaboration Across a Transformative Knowledge Network—Learning Across Disciplines, Cultures and Contexts? Sustainability, 12(6), 2499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062499