A Meta-Analysis on the Impact of Social Capital on Firm Performance in China’s Transition Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

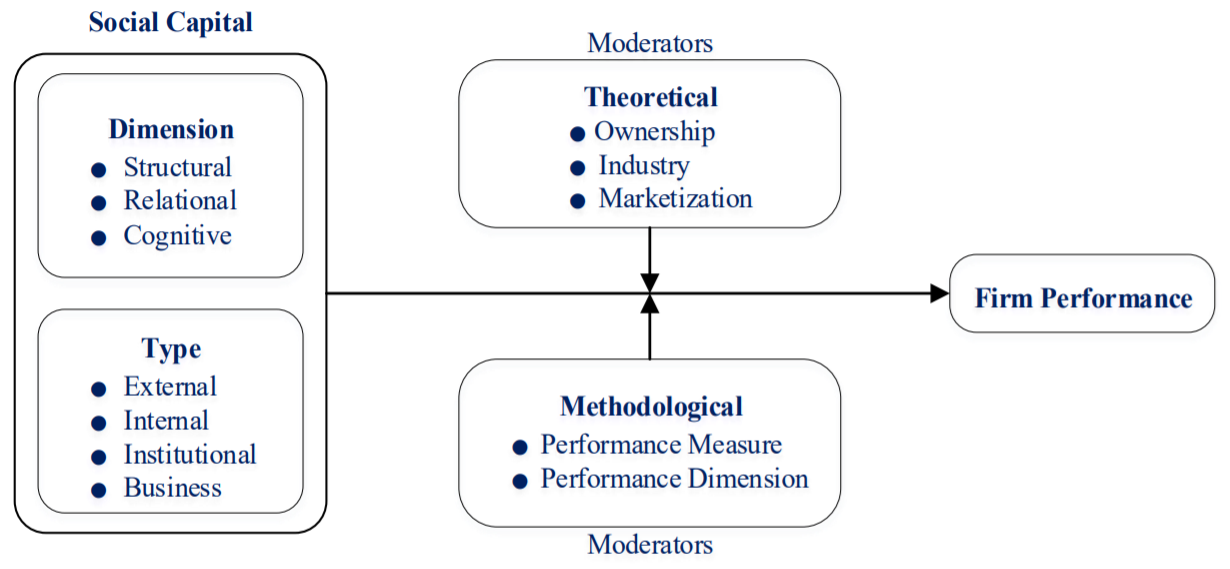

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Definition, Dimensions, and Types of Social Capital

2.2. Firm Performance

2.3. Social Capital and Firm Performance

2.4. Exploratory Theoretical Moderators

2.4.1. Ownership Structure

2.4.2. Industrial Type

2.4.3. Marketization Process

2.5. Exploratory Methodological Moderators

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

3.2. Coding and Measures

3.2.1. Social Capital

3.2.2. Theoretical Moderators

3.2.3. Methodological Moderators

3.3. Meta-analysis Procedures

4. Results

4.1. Main Effects of Social Capital on Firm Performance

4.2. Theoretical Moderator Analysis

4.2.1. Ownership Structure

4.2.2. Industrial Type

4.2.3. Marketization Process

4.3. Methodological Moderators Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings

5.1.1. The Aspects of Social Capital

5.1.2. The Aspects of Theoretical Moderators

5.1.3. The Aspects of Methodological Moderators

5.2. Research Contributions

5.3. Management Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhagavatula, S.; Elfring, T.; van Tilburg, A. How social and human capital influence opportunity recognition and resource mobilization in India’s handloom industry. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batjargal, B. Social capital and entrepreneurial performance in Russia: A longitudinal study. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 535–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfring, T.; Hulsink, W. Networks in entrepreneurship: The case of high-tech firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2003, 21, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E. Can guanxi be a source of sustained competitive advantage for doing business in China? Acad. Manag. Exec. 1998, 12, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, I.Y.; Tung, R.L. Achieving business success in Confucian societies: The importance of guanxi. Organ. Dyn. 1996, 25, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T.E.; Sorensen, O. Strategic networks and entrepreneurial ventures. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, W.; Arzlanian, S.; Elfring, T. Social capital of entrepreneurs and small firm perform: A meta-analysis of contextual and methodological moderators. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, H.; Wei, S.; Gu, J. Top managers’ managerial ties, supply chain integration, and firm performance in China: A social capital perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 74, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Yang, J.H.; Bai, X.; Che, Y.; Zhan, H.Q. The dark side of social capital: Perspective of relational embeddedness. China Soft Sci. 2012, 10, 104–116. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H.; Luo, Y. Guanxi and organizational dynamics: Organizational networking in Chinese firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tanaka, A. From hierarchy to hybrid: The evolving nature of inter- firm governance in China’s automobile groups. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Walker, G. How much does owner type matter for firm performance? Manufacturing firms in China 1998–2007. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Wu, Z.Y. Supply-demand imbalance and supply-side structural reform. Manag. Word 2017, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.Y.; Zhou, J.J.; Wang, G.H. The relationships among social capital, incubated enterprises’ absorptive capacity and innovation incubation performance. Sci. Res. Manag. 2014, 35, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Lettice, F.; Zhao, X. The impact of social capital on mass customization and product innovation capabilities. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.E.; Schmidt, F.L. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings; Sage Publications Inc.: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Samba, C.; Van, K.D.; Miller, C.C. The Impact of Strategic Dissent on Organizational Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Integration. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koka, B.; Prescott, J.E. Strategic alliance as social capital: A multinational view. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, B.; Leem, B. The effect of the supply chain social capital. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2013, 113, 324–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Huang, J.; Wang, B. A research on the relationship between board social Capital and CEO power on R&D investment: An evidence from the GEM listed Corporation. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 4, 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Atuahene-Gima, K. Product innovation strategy and the performance of new technology ventures in China. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, N.; Ramanujam, V. Measurements of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. Technology strategy and new venture performance: A study of corporate-sponsored and independent biotechnology ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 1996, 11, 289–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih, W.H.; Huang, L.C.; Yang, T.J. Prior knowledge, transformative learning and performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Norhria, N.; Zaheer, A. Guest editors’ introduction to the special issue: Strategic networks. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y. The role of Managers Political Networking and Functional Experience in New Venture Perform: Evidence from China’s Transition Economy. Strateg. Manag. 2007, 28, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoraki, C.; Messeghem, K.; Rice, M.P. A social capital approach to the development of sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: An explorative study. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 51, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y.D. Managerial Ties and Firm Performance in a Transition Economy: The Nature of A Micro-macro Link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Liu, Y.; Chin, T. The effect of technology management capability on new product development in China’s service-oriented manufacturing firms: A social capital perspective. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2018, 24, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xu, E.; Jacobs, M. Managerial political ties and firm performance during institutional transitions: An analysis of mediating mechanisms. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjosvold, D.; Peng, A.C.; Chen, Y.F. Business and government interdependence in China: Cooperative goals to develop business and industry. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2008, 25, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E. In search of legitimacy: The private entrepreneur in China. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1996, 21, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, K.R.; Pearce, J.L. Guanxi good connections as substitutes for institutional support. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1641–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A.; Zaheer, S. Catching the wave: Alertness, responsiveness, and market influence in global electronic networks. Manag. Sci. 1997, 43, 1493–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukoco, B.M.; Hardi, H.; Qomariyah, A. Social capital, relational learning, and performance of suppliers. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T. The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.; Van Den Bosh, F.A.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruef, M. Strong ties, weak ties and islands: Structural and cultural predictors of organizational innovation. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.J.; Behrens, B.; Krackhardt, D. Redundant governance structures: An analysis of structural and relational embeddedness in the steel and semiconductor industries. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.L. Chinese Marketization Index; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskisson, R.E.; Eden, L.; Lau, C.M. Strategy in emerging economies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 249–267. [Google Scholar]

- Puffer, S.M.; McCarthy, D.J.; Boisot, M. Entrepreneurship in Russia and China: The impact of formal institutional voids. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Poppo, L.; Zhou, K.Z. Do managerial ties in China always produce value? Competition, uncertainty, and domestic vs. foreign firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidis, R.; Estrin, S.; Mickiewicz, T. Institutions and entrepreneurship development in Russia: A comparative perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 656–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijk, R.; Jansen, J.P.J.; Lyles, M.A. Inter- and Intra-Organizational Knowledge Transfer: A Meta-Analytic Review and Assessment of its Antecedents and Consequences. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 830–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Heller, D.; Mount, M.K. Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. Apples and oranges: The search for moderators in meta-analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2003, 6, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V.; Vevea, J.L. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyskens, I.; Krishnan, R.; Steenkamp, J.E.M. A review and evaluation of meta-analysis practices in management research. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 393–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NU, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T.; Zhao, G. Top management support, inter-organizational relationships and external involvement. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 526–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Zhu, J.; Bao, H. High-performance human resource management and firm performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 353–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, E.; Peres, R. The effect of social networks structure on innovation performance: A review and directions for research. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2018, 36, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Oh, H.; Swaminathan, A. Framing Interorganizational Network Change: A Network Inertia Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 704–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Province | Average | Province | Average | Province | Average | Province | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhejiang | 9.157 | Chongqing | 6.774 | Hunan | 5.835 | Yunnan | 4.730 |

| Shanghai | 9.009 | Liaoning | 6.741 | Jilin | 5.713 | Ningxia | 4.436 |

| Guangdong | 8.794 | Anhui | 6.427 | Guangxi | 5.628 | Guizhou | 4.277 |

| Jiangsu | 8.736 | Hubei | 6.184 | Hainan | 5.441 | Gansu | 3.901 |

| Beijing | 8.029 | Henan | 6.166 | Heilongjiang | 5.347 | Xinjiang | 3.644 |

| Fujian | 7.669 | Sichuan | 6.158 | Shaanxi | 4.926 | Qinghai | 2.768 |

| Tianjin | 7.874 | Jiangxi | 5.878 | InnerMongolia | 4.903 | Tibet | 1.101 |

| Shandong | 7.314 | Hebei | 5.849 | Shanxi | 4.831 |

| Variable | K | N | RW | RC | Se2 | Sr2 | % Variance Due to Sampling Error | 95% Confidence Interval | Q Statistic x2 | Fail-Safe N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall relationship | 106 | 26845 | 0.199 | 0.244 | 0.004 | 0.043 | 9.67% | (0.164,0.250) | 1123.202 *** | 10388 |

| Structure dimension | 28 | 7017 | 0.260 | 0.305 | 0.004 | 0.029 | 12.91% | (0.180,0.343) | 209.092 *** | 2769 |

| Relationship dimension | 36 | 8062 | 0.312 | 0.365 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 12.25% | (0.251,0.381) | 327.572 *** | 6520 |

| Cognitive dimension | 29 | 7129 | 0.286 | 0.341 | 0.004 | 0.042 | 8.82% | (0.189,0.359) | 350.733 *** | 3488 |

| External social capital | 80 | 21147 | 0.185 | 0.221 | 0.003 | 0.037 | 9.53% | (0.173,0.262) | 850.491 *** | 4453 |

| Internal social capital | 21 | 6345 | 0.267 | 0.314 | 0.003 | 0.044 | 7.22% | (0.192,0.392) | 363.424 *** | 2837 |

| Institutional social capital | 19 | 4169 | 0.103 | 0.130 | 0.005 | 0.027 | 20.68% | (0.049,0.193) | 68.796 *** | 185 |

| Business social capital | 17 | 3790 | 0.129 | 0.150 | 0.005 | 0.023 | 23.50% | (0.070,0.211) | 49.160 *** | 217 |

| Social Capital Variable | K | N | RW | RC | Se2 | Sr2 | % Variance Due to Sampling Error | 95% Confidence Interval | Q Statistic x2 | Z-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership Structure a | ||||||||||

| State-owned | 3 | 625 | 0.125 | 0.150 | 0.005 | 0.049 | 11.33% | (−0.706,1.152) | 47.586 *** | 0.190 |

| Private | 9 | 4739 | 0.134 | 0.169 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 10.01% | (0.018,0.309) | 100.132 *** | |

| Industrial Type a | ||||||||||

| Low-tech | 22 | 5484 | 0.195 | 0.236 | 0.004 | 0.029 | 13.47% | (0.134,0.300) | 153.639 *** | 1.644 † |

| High-tech | 20 | 4074 | 0.257 | 0.312 | 0.004 | 0.026 | 15.89% | (0.214,0.411) | 135.548 *** | |

| External social capital *Low-tech | 22 | 5484 | 0.195 | 0.236 | 0.004 | 0.027 | 14.18% | (0.134,0.300) | 185.480 *** | 0.933 |

| External social capital *High-tech | 12 | 2447 | 0.244 | 0.300 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 21.96% | (0.127,0.447) | 74.469 *** | |

| Internal social capital *low-tech | 3 | 699 | 0.172 | 0.208 | 0.004 | 0.036 | 11.028% | (−0.382,0.794) | 30.464 *** | 0.611 |

| Internal social capital *High-tech | 6 | 1518 | 0.193 | 0.221 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 43.93% | (0.106,0.458) | 26.391 *** | |

| Structure dimension *Low-tech | 6 | 1164 | 0.205 | 0.230 | 0.005 | 0.054 | 8.74% | (0.019,0.391) | 35.947 *** | 1.146 |

| Structure dimension *High-tech | 11 | 2714 | 0.256 | 0.317 | 0.004 | 0.027 | 13.14% | (0.154,0.358) | 90.288 *** | |

| Relationship dimension *Low-tech | 9 | 1854 | 0.317 | 0.387 | 0.004 | 0.015 | 26.59% | (0.238,0.396) | 31.861 *** | 1.047 |

| Relationship dimension *High-tech | 14 | 3041 | 0.305 | 0.357 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 12.17% | (0.274,0.464) | 128.091 *** | |

| Cognitive dimension *Low-tech | 5 | 1013 | 0.284 | 0.340 | 0.004 | 0.034 | 12.11% | (0.121,0.447) | 40.103 *** | 0.201 |

| Cognitive dimension *High-tech | 11 | 2721 | 0.228 | 0.292 | 0.004 | 0.034 | 10.84% | (0.114,0.342) | 115.799 *** | |

| Marketization Process a | ||||||||||

| Low-level | 7 | 2094 | 0.374 | 0.448 | 0.002 | 0.024 | 10.15% | (0.235,0.575) | 89.550 *** | 2.344 * |

| High-level | 36 | 6888 | 0.194 | 0.237 | 0.005 | 0.034 | 14.02% | (0.160,0.300) | 214.753 *** | |

| External social capital *Low-level | 7 | 2094 | 0.374 | 0.448 | 0.002 | 0.022 | 10.36% | (0.235,0.575) | 89.550 *** | 2.636 ** |

| External social capital *High-level | 30 | 6368 | 0.187 | 0.227 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 22.25% | (0.142,0.277) | 150.250 *** | |

| Structure dimension *Low-level | 3 | 716 | 0.311 | 0.353 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 13.70% | (0.158,0.464) | 19.300 *** | 0.307 |

| Structure dimension *High-level | 6 | 1039 | 0.211 | 0.256 | 0.006 | 0.088 | 6.68% | (0.050,0.472) | 90.342 *** | |

| Relationship dimension *Low-level | 3 | 716 | 0.399 | 0.460 | 0.007 | 0.045 | 14.49% | (0.260,0.538) | 9.597 ** | 1.531 |

| Relationship dimension *High-level | 10 | 1545 | 0.231 | 0.289 | 0.006 | 0.041 | 15.41% | (0.099,0.364) | 67.902 *** | |

| Cognitive dimension *Low-level | 3 | 716 | 0.355 | 0.461 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 12.77% | (0.202,0.509) | 17.828 *** | 1.604 |

| Cognitive dimension *High-level | 7 | 1421 | 0.206 | 0.247 | 0.005 | 0.022 | 21.72% | (0.087,0.325) | 28.571 *** | |

| Social capital Variable | K | N | RW | RC | Se2 | Sr2 | % Variance Due to Sampling Error | 95% Confidence Interval | Q Statistic x2 | Z-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance measure | ||||||||||

| Subjective scale | 87 | 19382 | 0.249 | 0.306 | 0.004 | 0.036 | 10.59% | (0.232,0.319) | 838.517 *** | 5.478 *** |

| Objective quantified | 20 | 7636 | 0.044 | 0.053 | 0.003 | 0.013 | 20.00% | (0.007,0.145) | 75.714 *** | |

| Performance dimension | ||||||||||

| Growth | 22 | 5391 | 0.187 | 0.218 | 0.004 | 0.036 | 10.31% | (0.147,0.342) | 167.173 *** | 2.478 *a |

| Profit | 18 | 6534 | 0.068 | 0.084 | 0.003 | 0.028 | 18.87% | (0.032,0.170) | 123.709 *** | 4.396 ***b |

| Non-financial | 49 | 11280 | 0.268 | 0.327 | 0.004 | 0.035 | 10.73% | (0.222,0.342) | 538.768 *** | 1.021 c |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

LYU, T.; JI, X. A Meta-Analysis on the Impact of Social Capital on Firm Performance in China’s Transition Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072642

LYU T, JI X. A Meta-Analysis on the Impact of Social Capital on Firm Performance in China’s Transition Economy. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072642

Chicago/Turabian StyleLYU, Tu, and Xiangfeng JI. 2020. "A Meta-Analysis on the Impact of Social Capital on Firm Performance in China’s Transition Economy" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072642

APA StyleLYU, T., & JI, X. (2020). A Meta-Analysis on the Impact of Social Capital on Firm Performance in China’s Transition Economy. Sustainability, 12(7), 2642. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072642