An Empirical Analysis on DPRK: Will Grain Yield Influence Foreign Policy Tendency?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model and Method

2.1. Data

2.2. Empirical Orthogonal Function

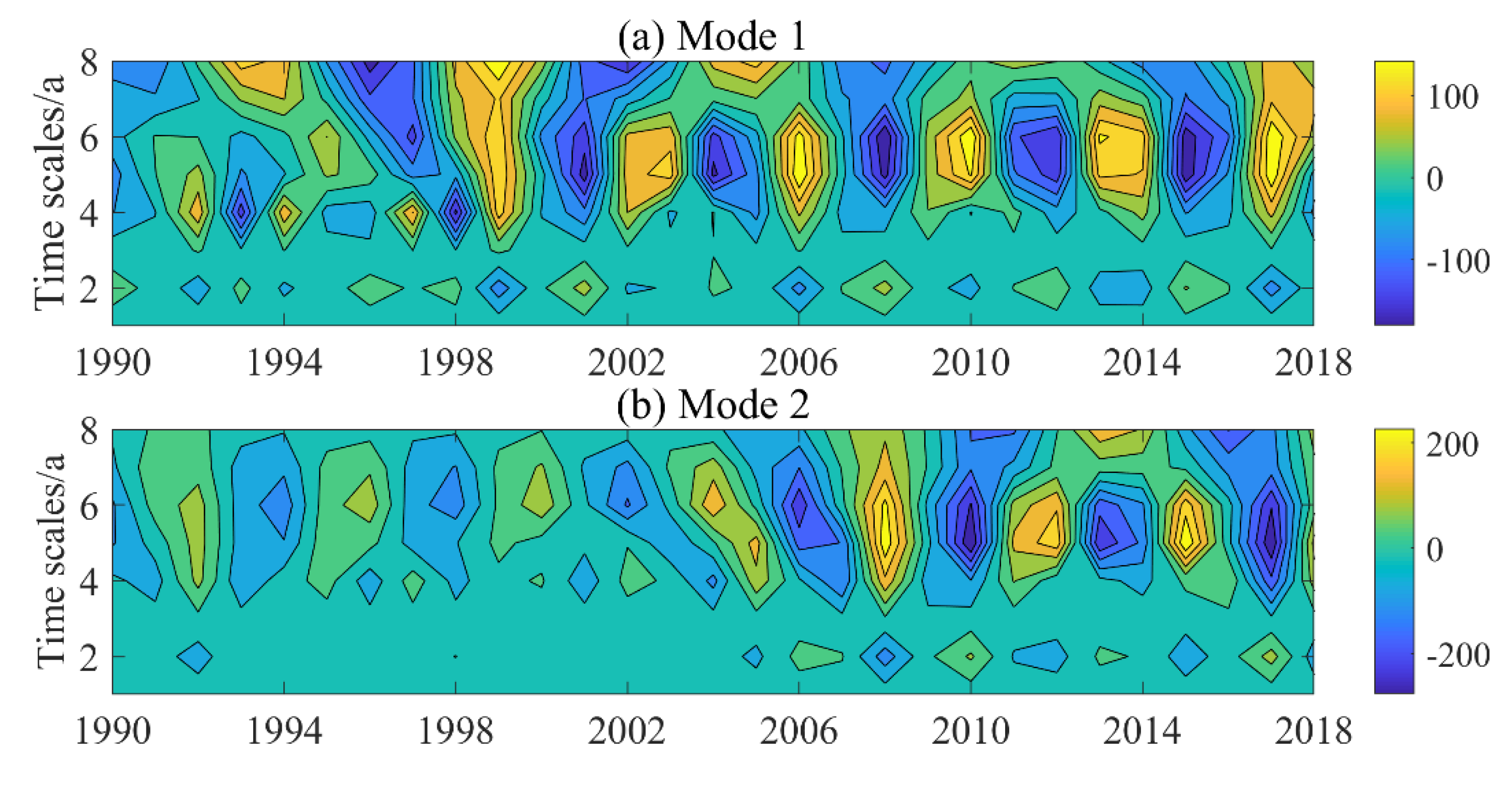

2.3. Wavelet Transform

2.4. Multivariable Linear Regression

3. Discussions

4. Conclusions

- North Korea’s grain output is one of the important indicators to predict its foreign policy tendency towards hawkish or dovish. When grain production increases, North Korea’s foreign policy tends to be hawkish. When the grain output is reduced, the dovish tendency of North Korea’s foreign policy will rise.

- Due to the hysteretic nature of the grain output to its foreign policy tendency (hawks or doves), with a lag time of about three years, which means the increase in grain production will give rise to signs of hawkish tendency, while the decrease in grain production will trigger the return of dovish tendency three years later.

- Currently, the Korean Peninsula is at a very critical moment with its extremely sensitive political situation. The uncertainties have also increased as a result of the impasse of the denuclearization negotiations with the United States. As North Korea’s grain output is one of the important indicators for predicting its foreign policy tendency, we can judge the direction of North Korea’s foreign policy based on the statistics of grain production, help promote North Korea and the United States to have peaceful negotiations, and effectively promote denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

- North Korea’s grain output can be taken as an important reference for predicting the choice of its foreign policy, which is an important determinant of whether Northeast Asia’s regional cooperation can proceed smoothly. Therefore, we can use grain output to judge the stability and sustainability of Northeast Asia’s regional relations and to advance effective development of economic activities such as trade and investment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Output (Thousand Tons) |

|---|---|

| 1990 | 4020 |

| 1991 | 4427 |

| 1992 | 4268 |

| 1993 | 3884 |

| 1994 | 4125 |

| 1995 | 3451 |

| 1996 | 3690 |

| 1997 | 3489 |

| 1998 | 3886 |

| 1999 | 4222 |

| 2000 | 3590 |

| 2001 | 3946 |

| 2002 | 4134 |

| 2003 | 4253 |

| 2004 | 4311 |

| 2005 | 4537 |

| 2006 | 4484 |

| 2007 | 4005 |

| 2008 | 4306 |

| 2009 | 4108 |

| 2010 | 4417 |

| 2011 | 4325 |

| 2012 | 4676 |

| 2013 | 4806 |

| 2014 | 4802 |

| 2015 | 4512 |

| 2016 | 4823 |

| 2017 | 4701 |

| 2018 | 4558 |

| Year | ROK | USA | China | Japan | EU | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 150,000 | 0 | 0 | 378,000 | 0 | 16,492 | 544,492 |

| 1996 | 2754 | 22,196 | 100,000 | 137,521 | 0 | 242,728 | 505,199 |

| 1997 | 60,035 | 192,614 | 150,000 | 640 | 201,112 | 299,180 | 903,581 |

| 1998 | 48,455 | 231,361 | 151,105 | 67,000 | 103,687 | 188,954 | 790,562 |

| 1999 | 12,204 | 589,053 | 200,638 | 0 | 68,010 | 130,151 | 1,000,056 |

| 2000 | 351,703 | 351,253 | 280,026 | 99,999 | 70,504 | 77,949 | 1,231,434 |

| 2001 | 198,000 | 318,729 | 419,834 | 500,000 | 12,595 | 58,800 | 1,507,958 |

| 2002 | 457,800 | 222,153 | 329,606 | 0 | 11,606 | 156,946 | 1,178,111 |

| 2003 | 542,191 | 46,755 | 212,492 | 0 | 69,185 | 73,781 | 944,404 |

| 2004 | 406,510 | 105,030 | 132,319 | 80,803 | 10,989 | 109,155 | 844,806 |

| 2005 | 492,743 | 27,699 | 451,346 | 48,084 | 8450 | 69,001 | 1,097,323 |

| 2006 | 79,500 | 0 | 207,251 | 0 | 20,703 | 307,454 | |

| 2007 | 430,550 | 0 | 264,211 | 0 | 1291 | 24,475 | 720,526 |

| 2008 | 58,605 | 171,110 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 145,485 | 375,239 |

| 2009 | 0 | 121,000 | 116,179 | 0 | 63,485 | 300,664 | |

| 2010 | 22,994 | 1470 | 576 | 0 | 79,124 | 104,164 | |

| 2011 | 7 | 0 | 2164 | 0 | 1159 | 58,807 | 62,137 |

| 2012 | 240,074 | 0 | 2912 | 129,569 | 372,555 |

| Year | Events | Hawk-Dove Scores (Dove=D, Hawk=H) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D | H | ||

| 1990 | Sept.: A delegation headed by former deputy prime minister Shin Kanemaru, a prominent figure in Liberal Democratic Party of Japan, met Kim Il Sung three times and issued a three-party joint statement with the Korean Workers’ Party. | 10 | 0 |

| Sep.4: Premier Yon Hyong-muk of North Korea’s Political Council and South Korean Prime Minister Kang Young-hoon hold their first premier talks in Seoul. | 80 | 0 | |

| 1991 | Jan.: Negotiations to establish diplomatic relations between DPRK and Japan starts. | 60 | 0 |

| Dec.: North Korea and South Korea signed the Inter-Korean Basic Agreement. | 80 | 0 | |

| Dec.31: North Korea and South Korea signed the Joint Declaration on the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula in Panmunjom. | 80 | 0 | |

| 1992 | Jan: North Korea and International Atomic Energy Agency signed Nuclear Safety Agreement. | 80 | 0 |

| Feb.19: During the sixth North-South talks between North Korea and South Korea, the Prime Ministers of the two countries respectively read out the Agreement on Reconciliation, Non-aggression, and Cooperation and Exchange between North and South and Joint Declaration on the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, which were approved by President Kim Il Sung and President Roh Tae-woo. | 80 | 0 | |

| Apr.9: The third session of the Ninth Supreme People’s Assembly of North Korea approved the Nuclear Safety Agreement signed between North Korea and the International Atomic Energy Agency. | 80 | 0 | |

| 1993 | Mar.: North Korea held a rally with 100,000 people against South Korea-US military exercise in Pyongyang. | 0 | 30 |

| Mar.12: North Korea announced withdrawal from Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in 3 Months. | 0 | 70 | |

| 1994 | Jun.13: North Korea withdrew from International Atomic Energy Agency. | 0 | 70 |

| Jun.15–18: Former US President Carter went to Pyongyang to mediate and reached a Framework agreement on the DPRK nuclear issue with the North Korean government. | 80 | 0 | |

| Sep.21: North Korea and United States sign Geneva Nuclear Framework Agreement, and North Korea agrees to freeze nuclear facilities. | 80 | 0 | |

| 1995 | Mar.: Japan’s major parties formed a joint delegation to visit Pyongyang and jointly signed an agreement with the Korean Workers’ Party on the resumption of diplomatic ties between Japan and North Korea. | 60 | 0 |

| Jun.: North Korea has accepted a plan to provide South Korean light water reactors under the name of the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization. | 60 | 0 | |

| 1996 | May.21: Vice Premier of North Korea Hong Song-nam visits China. | 5 | 0 |

| Jul.10: Secretary General of the State Council Luo Gan visits North Korea and Vice Premier Kim Yoon-heok visits China. | 5 | 0 | |

| Dec.29: North Korea has officially issued an official apology on the infiltration of special forces into South Korea, expressing deep regret over the incident and stating that it will make efforts to ensure that such incidents will not happen again. | 30 | 0 | |

| 1997 | Feb.: North Korea’s senior official Hwang Jang-yop defected to South Korea via China. Taiwan intends to export nuclear waste to North Korea, which makes the relations between China and North Korea tense. North Korea rejected China and avoided substantive negotiations with China in the Quadripartite Talks held in August. | 0 | 30 |

| 1998 | Aug.: According to commercial satellite images, the United States questioned North Korea had hidden underground nuclear facilities and requested for inspection, which North Korea firmly denied. North Korea launched the artificial earth satellite “Kwangmyongsong-1”, while the United States believes it launched the long-range ballistic missile “Taepodong-1”. | 0 | 60 |

| 1999 | May.25–28: Former U.S. Defense Secretary Perry visited North Korea as President Clinton’s special envoy and had extensive contacts with North Korean leaders. This is the first time a senior U.S. official has visited North Korea in 40 years. | 80 | 0 |

| Jun.: Kim Yong-nam, chairman of the Standing Committee of North Korea’s Supreme People’s Assembly, led a national delegation to pay an official goodwill visit to China. | 5 | 0 | |

| Sept.: Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxuan visits North Korea. | 5 | 0 | |

| 2000 | Jun.13–15: North Korean leader Kim Jong Il and South Korean President Kim Dae-jung held a historic meeting in Pyongyang. | 90 | 0 |

| July 19–20: Russian President Putin visits North Korea. | 10 | 0 | |

| Sept.23: Kim Jong Il meets US Secretary of State Albright. | 80 | 0 | |

| 2001 | Jan.: George Bush took office as President of the United States, then adjusted his policy towards North Korea, listed North Korea as an “axis of evil” country and threatened to carry out a “pre-emptive nuclear strike” against North Korea. | 0 | 30 |

| Aug.4–5: Kim Jong Il held talks with Russian President Putin in Moscow and both sides issued North Korea-Russia Moscow Declaration. | 20 | 0 | |

| 2002 | Jun.29: North Korea and South Korean warships exchanged fire in the waters of Yeonpyeong Island in the Yellow Sea. | 0 | 50 |

| Aug., Kim Jong Il visited Russia again and visited Russia’s Far East. | 20 | 0 | |

| Sept.17: Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi visited North Korea. Leaders of the two sides held talks and issued the Japan-DPRK Pyongyang Declaration. | 80 | 0 | |

| Sept.3: US President’s Special Envoy, Assistant Secretary of State Jim Kelly, announced that North Korea had “admitted” its uranium enrichment program after his visit to Pyongyang, and accused North Korea of developing nuclear weapons. | 0 | 30 | |

| Dec.22: The United States has stopped supplying heavy oil to North Korea on the grounds that North Korea violated DPRK-U.S. Nuclear Agreed Framework. Later, North Korea announced that it would lift the nuclear freeze, dismantle the monitoring equipment installed by the International Atomic Energy Agency in its nuclear facilities and restart the nuclear facilities used for electricity production. | 0 | 50 | |

| 2003 | Jan.10: North Korea announces its withdrawal from Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. | 0 | 70 |

| Apr.23–25: China, North Korea and the United States held tripartite talks in Beijing. | 10 | 0 | |

| May.30-Jun.1: US Congressman Delegation visits North Korea. In talks with North Korea’s foreign minister, the United States asked North Korea to “give up its nuclear program first,” while North Korea asked the United States to change its hostile policy towards North Korea. | 10 | 15 | |

| Jul.12–15: Deputy Foreign Minister Dai Bingguo visited North Korea as a special envoy of the Chinese government and held talks with Kang Sok-ju, the first deputy foreign minister of North Korea. | 5 | 0 | |

| Aug.27–29: China, North Korea, United States, South Korea, Russia and Japan hold first round of the Six-Party Talks in Beijing. | 10 | 0 | |

| Oct.29–31: Wu Bangguo, member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and chairman of the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress, led a Chinese national delegation to visit North Korea. During his visit, he had an in-depth exchange of views with Kim Jong Il and other North Korean leaders on the peninsula nuclear issue. | 10 | 0 | |

| 2004 | Feb.25–28: In the second round of the Six-party Talks, North Korea emphasized that North Korea will abandon its nuclear program only when the United States abandon its hostile policy toward North Korea. | 10 | 15 |

| May.22: North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong Il and Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi started talks in Pyongyang at 11:02 am local time. | 60 | 0 | |

| Jun.23–26: The parties held the third round of the Six-party Talks. North Korea further clarified its willingness to abandon nuclear weapons and stated for the first time that it could openly abandon all nuclear weapons and related plans. | 60 | 0 | |

| 2005 | May.11: North Korea announced the removal of 8,000 spent fuel rods from nuclear reactors, restarted a 5 MW nuclear reactor frozen under the framework agreement, and resumed construction of 50,000 kW and 200,000 kW nuclear reactors. | 0 | 50 |

| Sept.19: The fourth round of the Six-party Talks worked out a joint statement. | 80 | 0 | |

| Oct.28–30: At the invitation of Kim Jong Il, then General Secretary of the Korean Workers Party and Chairman of the National Defense Committee, Hu Jintao, then General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee, State President, and Chairman of the Central Military Commission, visited North Korea. | 10 | 0 | |

| Nov.9: The first phase of the fifth round of the Six-party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue was held in Beijing, contributing to the guiding Chairman's Statement. | 80 | 0 | |

| 2006 | Jan.10–18: Kim Jong Il paid an informal visit to China, and visited Hubei, Guangdong, Beijing and other provinces. | 20 | 0 |

| July.5: North Korea fired the “Taepodong-2”, long-range missile for test. | 0 | 60 | |

| July.16: The North Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement, strongly opposing UN Resolution 1695, and stated that North Korea will not be bound by this resolution. | 0 | 50 | |

| Oct.3: North Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement announcing that North Korea would conduct scientific research on nuclear tests and stressing that North Korea is still committed to realizing denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula through dialogue and negotiation. | 30 | 50 | |

| Oct.9: North Korea announced a successful underground nuclear test. | 0 | 100 | |

| Dec.18–22: The second phase of the fifth round of the Six-party Talks was held in Beijing. | 10 | 0 | |

| 2007 | Feb.8–13: The third phase of the fifth round of the Six-party Talks. | 10 | 0 |

| Mar.13–14: The Head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, ElBaradei paid a visit to North Korea. The North Korea expressed its willingness to cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency to close the Yongbyon nuclear facility. | 60 | 0 | |

| Mar.19–22: The sixth round of the Six-party Talks was held in Beijing. | 10 | 0 | |

| Jun.21–22: Hill, the head of the U.S. delegation to the Six-party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue and Assistant Secretary of State, visited North Korea. | 60 | 0 | |

| July.14: After the first batch of 6,200 tons of heavy oil delivered by South Korea arrived at North Korea’s Sonbong Port, the North Korea closed the Yongbyon nuclear facility. On the same day, the inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency returned to North Korea after a lapse of five years and went to the Yongbyon area to monitor and verify the closure of nuclear facilities. | 70 | 0 | |

| July.20: The Head of Delegation Meeting of the Sixth Round of Six-Party Talks drew the curtain in Beijing with a press communique. The parties reached a four-point framework consensus on work to do in the next stage and decided a three-step practice. | 80 | 0 | |

| Sept.1–2: The second round of talks between the US-DPRK bilateral working groups was held in Geneva, and the two sides agreed on North Korea’s comprehensive declaration of its nuclear program and the defunctionalization of all nuclear facilities. | 80 | 0 | |

| Oct.2–4: The second North Korea and South Korea summit meeting was held. | 90 | 0 | |

| Oct.3: The second phase of the sixth round of the Six-Party Talks adopted the joint document Implementing the Second Phase of the Joint Statement. | 80 | 0 | |

| Dec.3–5: US Assistant Secretary of State, head of the US delegation to the Six-party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue, Hill visited North Korea. He inspected the Yongbyon nuclear facility and discussed North Korea’s declaration of nuclear program with North Korean officials. | 70 | 0 | |

| Dec.14: US President Bush appealed to North Korea in Washington, asking it to comprehensively declare its nuclear program and nuclear proliferation. Kim Ge-sik, chief of staff of the Korean People’s Army, said in Pyongyang on the 23rd that Korean peninsula is still in tense as the United States continues its war policy. | 0 | 20 | |

| 2008 | Jan.4: The North Korea stressed that they had firmly implemented the Joint Document Implementation of Joint Statement Phase II signed in October 13, noticing that the relevant parties, such as the United States, had not fulfilled the agreement in a timely manner. They also pointed out that North Korea should not be responsible for the delay of the implementation of the Joint Document. | 0 | 20 |

| 0 | 15 | ||

| Mar.13: the Six-party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue were held in Geneva. The heads of the US and North Korean delegations attended but failed to reach agreement on specific issues such as North Korea’s declaration of a nuclear program. | 60 | 0 | |

| Apr.8: the Six-party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue were held in Singapore. The heads of the US and North Korean delegations attended and agreed on some key issues in implementing the documents. | 60 | 0 | |

| Apr.22–24: The U.S. working group on North Korea’s nuclear issue visited Pyongyang and discussed with North Korea specific issues related to the implementation of joint documents, including issues such as the content of North Korea’s nuclear program declaration. | 80 | 0 | |

| May.8: North Korea submitted North Korean nuclear plan documents including more than 18,000 pages. The US government has taken the move as an “important step” in verifying North Korea’s nuclear program. In June: Xi Jinping, the member of the Central Politburo Standing Committee of the CPC and Vice President of China, visited the North Korea. | 5 | 0 | |

| Jun.10: The U.S. working group on North Korea’s nuclear issue visited Pyongyang for the third time and discussed with North Korea the technical and transactional issues of the de-functionalization of North Korea’s nuclear facilities, as well as political and economic compensation by the parties concerned. | 50 | 0 | |

| Jun.11: The working group on economic and energy cooperation at the Six-party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue held a meeting in Panmunjom. | 10 | 0 | |

| Jun.11–12: North Korea and Japan held intergovernmental working talks in Beijing. | 20 | 0 | |

| Jun.26: North Korea submitted a declaration on its nuclear program, and the United States also launched the same day to remove North Korea from US list of countries that sponsor terrorism. | 80 | 0 | |

| Jun.27: North Korea blew down cooling towers at its nuclear facilities in Yongbyon. | 80 | 0 | |

| July.10–12: The head of the delegation of the Six-party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue was held in Diaoyutai, Beijing. | 10 | 0 | |

| July.23: The informal meeting of the six foreign ministers on the North Korean nuclear issue was held in Singapore. | 10 | 0 | |

| Oct.12: North Korea announced the restart of de-functionalization of nuclear facilities. IAEA investigators were granted access to the Yongbyon nuclear facility. | 80 | 0 | |

| 2009 | Jan13: The North Korea’s Foreign Ministry stated that North Korea would only give up its nuclear containment power when the United States withdraw the nuclear threat to North Korea and no longer protect South Korea in terms of nuclear. | 0 | 30 |

| Apr.13: North Korea announced its withdrawal from the Six-party Talks which focused on the North Korean nuclear issue and will restore the de-functionalized nuclear facilities as they were. | 0 | 80 | |

| Apr.5: North Korea announced the successful launch of the “kwangmyongsong-2”, the test communication satellite. Apr.29: The North Korea’s Foreign Ministry stated that if the UN Security Council does not “apology” for actions that violate North Korea’s autonomy, North Korea will take further self-defense measures, namely, conduct nuclear tests and test-fire intercontinental ballistic missiles again. | 0 | 60 | |

| May.8: A spokesman for North Korea’s Foreign Ministry said that North Korea will further strengthen its nuclear containment in accordance with its stated position because the US government has no change as before in its policy of hostility toward North Korea. | 0 | 40 | |

| May.25: North Korea’s Central News Agency reported that North Korea successfully conducted its second underground nuclear test. | 0 | 100 | |

| Jun.13: North Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was appointed to express its firm opposition to and condemnation of UN Security Council 1874 Resolution on North Korea’s nuclear test, and announced to safeguard national dignity and national autonomy with three measures if there is a full confrontation with the United States. | 0 | 50 | |

| July.2: South Korean media quoted military sources, saying that North Korea had fired four surface-to-ship short-range missiles in the east coast of North Korea that afternoon and evening. | 0 | 50 | |

| July.4: According to South Korea’s Yonhap News Agency, North Korea fired 7 missiles on the eastern sea at a missile base in Gangwon-do that day. | 0 | 50 | |

| Aug.4: Kim Jong Il welcomed former US President Clinton in Pyongyang. | 80 | 0 | |

| Aug.5: North Korea published that Kim Jong Il pardoned two detained US journalists. | 70 | 0 | |

| Sept.4: According to the North Korean Central News Agency, North Korea has successfully conducted experimental uranium enrichment, and the test has entered the final stage. | 0 | 40 | |

| Oct.5: Wen Jiabao, the member of the Central Politburo Standing Committee of the CPC and Premier of the State Council, talked with Kim Jong Il, General Secretary of the Korean Workers Party and Chairman of the National Defense Committee in Pyongyang, sharing the common goal in China-DPRK relations and the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. In December: Bosworth, the U.S. State Department’s special representative for North Korean policy, visited Pyongyang, marking the first official contacts of the two parties since the Obama administration took office. | 15 | 0 | |

| 2010 | Jan18: News came from the Korean Central News Agency: a spokesman for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the North Korea emphasized the necessity to settle the peace agreement before discussing the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula, and to abandon sanctions against North Korea before the Six-Party Talks. | 10 | 30 |

| Apr.21: The North Korea’s Foreign Ministry issued a memorandum in Pyongyang entitled “Korean Peninsula and Nuclear Issues”, stating that North Korea will participate in international nuclear disarmament on an equal footing with other nuclear powers. | 20 | 25 | |

| May.3–7: Kim Jong Il paid an informal visit to China and held talks with Hu Jintao. | 20 | 0 | |

| On March 26, 2010, the warship “Cheonan” was sunk by a torpedo attack from the North Korea. Consequently, the North Korean Peaceful Reunification Commission announced to server relations with South Korea and imposed sanctions on South Korea. | 0 | 70 | |

| In July: North Korea and US held high-level talks in Bali, Indonesia. | 10 | 0 | |

| Sept.29: North Korean Deputy Foreign Minister Park Ji-yeon said in a general debate at the UN General Assembly that North Korea will not give up its nuclear deterrence as long as the United States does not stop using its mailed fist. | 0 | 30 | |

| In October: North Korea and the United States held high-level talks in Geneva, Switzerland. | 10 | 0 | |

| Nov.23: South Korea fired dozens of artillery shells into the disputed waters of the North and South during its annual military exercise. To respond it, North Korea immediately shelled South Korea’s Yeonpeong Island artillery position. | 0 | 70 | |

| 2011 | Mar.15: A spokesman for North Korea’s Foreign Ministry said in Pyongyang that North Korea would participate unconditionally in the Six-Party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue and has no objection to discussing uranium enrichment during the Six-Party Talks. | 50 | 0 |

| July: At the invitation of the North Korean government, Zhang Dejiang, then member of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and vice premier of the State Council, led a Chinese delegation to visit the North Korea to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Friendship Cooperation and Mutual Assistance between the people’s Republic of China and the Democratic people’s Repulic of Korea. | 5 | 0 | |

| July.28–29: Kim Kye-gwan, First Deputy Prime Minister of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the North Korea, was invited to visit the United States to talk with the US Envoy for North Korea, Stephen Bosworth, on the resumption of the Six-Party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue. This is the first high-level dialogue between the two sides since 2009. | 60 | 0 | |

| Aug.24: Russian President Dmitri Anatolyevich Medvedev held talks with Kim Jong Il, chairman of the North Korean Defense Council, in Russia. Kim Jong Il informed Medvedev during the talks that North Korea was ready to return unconditionally to the Six-Party Talks and to stop producing nuclear materials and conducting nuclear tests during the negotiations. | 20 | 0 | |

| October: Li Keqiang, then the member of the Central Politburo Standing Committee of the CPC and Vice Premier of the State Council, visited North Korea. | 5 | 0 | |

| Oct.24: The United States and North Korea representatives held a two-day talk in Geneva, Switzerland on the resumption of the Six-Party Talks on the North Korean nuclear issue. | 10 | 0 | |

| 2012 | Feb.23–29: The third high-level talks between the North Korea and the United States were held in Beijing. As a result, the Leap Day agreement based on “freezing nucleus for compensation” was reached. | 70 | 0 |

| April: North Korea wrote “nuclear possession” into its Constitution. | 0 | 40 | |

| Apr.13: According to the Korean Central News Agency, North Korea launched the first application satellite “Kwangmyongsong-3” that morning. Later, the US government announced that it would abandon its previous food aid agreement with North Korea. | 0 | 60 | |

| July.20: A spokesman for North Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that North Korea had to reconsider the nuclear issue” as the United States did not change its hostile policy. | 0 | 30 | |

| 2013 | Feb.12: North Korea successfully conducted its third underground nuclear test. | 0 | 100 |

| Mar.13: North Korea suspended the North Korean Armistice Agreement signed in 1953 and declared that it is no longer bound by the non-aggression treaty. | 0 | 80 | |

| March: The route “nuclear weapons and economy advance together" was settled. | 0 | 40 | |

| Apr.2: A spokesperson for the North Korean General Administration of Atomic Energy stated that North Korea would restart the 5 MW graphite deceleration reactor in Yongbyon, which had been closed in 2007. | 0 | 50 | |

| Apr.3: North Korea closed the Kaesong industrial area which was established in cooperation with South Korea. At the meantime, South Koreans were asked to leave. | 0 | 50 | |

| May.18: North Korea fired a total of 4 short-range missiles into the Sea of Japan. Aug.10: North and South Korea again shelled near the northern border. | 0 | 50 | |

| 2014 | Jun.26–29: North Korea conducted at least 4 missile tests. | 0 | 50 |

| Oct.4: North Korea dispatched Hwang Pyong-so and other senior officials to attend the closing ceremony of the Asian Games in Incheon. | 50 | 0 | |

| Oct.7: North Korean and Korean Navy patrol boats began to fight with each other. | 0 | 50 | |

| Nov.20: A spokesman for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of North Korea issued a statement saying that what the United States are doing is actually forcing North Korea to continue a new round of nuclear tests. | 0 | 40 | |

| 2015 | May.20: A spokesperson for the Policy Bureau of the North Korean Defense Council stated that North Korea’s nuclear strike means have become miniaturized and diversified and warned all parties that these are North Korea’s inviolable measures to strengthen its self-defense capabilities. | 0 | 30 |

| July.21: North Korea noted that it would not resolve the nuclear issue on the Korean peninsula as The Iranian nuclear deal, saying “North Korea will never give up nuclear weapons.” | 0 | 40 | |

| Aug.25: North Korea and South Korea reached the “Aug.25 Agreement”. The two sides agreed on a number of issues including holding inter-governmental talks between the North and the South Korea, releasing the quasi-wartime status of the North Korea, and realizing reunion of separated families of North and South Korea. | 60 | 0 | |

| Sept.15: North Korea suggested that Yongbyon’s nuclear facility began to operate at “full capacity”. | 0 | 30 | |

| 2016 | Jan.6: North Korea announced that it successfully conducted its first hydrogen bomb test (the fourth nuclear test). | 0 | 100 |

| Feb.7: North Korea announced the launch of the “Kwangmyongsong-4” satellite with a long-range rocket. | 0 | 60 | |

| Mar.10: The North Korean Unified Peace Commission declared all economic cooperation and exchange agreements between the North and South Korea invalid and fired two “Scud” missiles. | 0 | 60 | |

| July-August: North Korea fired several missiles with a range of 500 kilometers into the eastern waters of the peninsula. | 0 | 50 | |

| Aug.18: The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of North Korea suggested that the situation on the Korean Peninsula has entered an “extremely dangerous stage”. If the United States dares to take “mad measures”, Pyongyang will destroy all US military bases in the Pacific. | 0 | 40 | |

| Aug.24: North Korea fired a submarine-launched ballistic missile into the eastern waters of the Korean Peninsula. | 0 | 50 | |

| Sept.5: North Korea fired another three ballistic missiles at sea. | 0 | 50 | |

| Sept.9: North Korea’s CCTV reported that North Korea successfully conducted a nuclear test that day. | 0 | 100 | |

| 2017 | Feb.12: North Korea fired a ballistic missile from the northwest of the country to the east. | 0 | 50 |

| Feb.13: Kim Jong-nam was assassinated. Diplomatic disputes broke out between North Korea and Malaysia. | 0 | 30 | |

| May.14: North Korea launched “Hwasong-12” long-range ballistic missile. | 0 | 80 | |

| July.3: North Korea fired a “Hwasong-14” intercontinental ballistic rocket for adjustment. | 0 | 90 | |

| Sept.3: North Korea conducted its sixth nuclear test at the Punggye-ri nuclear test site in Kilju County, North Hamgyong Province. | 0 | 100 | |

| Nov.29: North Korea fired the “Hwasong-15” intercontinental ballistic missile for adjustment. | 0 | 90 | |

| 2018 | Feb.9: A high-level delegation from North Korea visited South Korea and attended the opening ceremony of the The 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang. | 60 | 0 |

| Mar.25–28: Kim Jong Un paid informal visits to China. | 20 | 0 | |

| Apr.20: The Third Plenary Session of the Seventh Central Committee of the Korean Workers Party decided to suspend nuclear tests and intercontinental ballistic missile test launches from October 8, 2017, abandon the northern nuclear test site, and shift the overall cause of the party and the country to socialist economic construction . | 60 | 0 | |

| Apr.27: South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korea’s top leader Kim Jong-un held their first meeting at the “Peace House” of Panmunjom (on the Korean side). They signed the the Panmunjom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula, announcing that the two parties will work hard to realize the denuclearization and turn the armistice agreement into a peace treaty. | 90 | 0 | |

| May.7–8: Xi Jinping and Kim Jong Un meet in Dalian | 20 | 0 | |

| May.24: North Korea blasted a number of tunnels and ancillary facilities at the Punggye-ri nuclear test site in Kilju County, North Hamgyong Province, and announced that the nuclear test site was officially abandoned. | 70 | 0 | |

| May.26: South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korea’s top leader Kim Jong-un held their second meeting. | 90 | 0 | |

| Jun.12: The first meeting of US and North Korean leaders was held in Singapore. | 100 | 0 | |

| Jun.19–20: Kim Jong Un visited China. | 20 | 0 | |

| Sept.18–20: South Korean President Moon Jae-in and Chairman of the State Council of Korea Kim Jong-un hold the third meeting. | 90 | 0 | |

| Dec.26: The commencement ceremony of the Korean railway and highway docking project. | 50 | 0 | |

References

- Song, W. How to United Diplomacy and Domestic Affairs: A Perspective of Positional Realism. Q. J. Int. Polit. 2018, 4, 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.H. Korean unification studies series, 7. In Korea and the Major Powers: An Analysis of Power Structures in East Asia; Research Center for Peace and Unification of Korea: Seoul, Korea, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, V. Nuclear North Korea: Politics of Six-Way Talks. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2007, 42, 741–742. [Google Scholar]

- Noland, M. Famine and reform in North Korea. Asian Econ. Pap. 2004, 3, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, W.; Shen, X.; Yuan, G.; Wang, J. Water Environment Management and Performance Evaluation in Central China: A Research Based on Comprehensive Evaluation System. Water 2019, 11, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yuan, G.; Han, J. Is China’s air pollution control policy effective? Evidence from Yangtze River Delta cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 110–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, W. Does Whistleblowing Work for Air Pollution Control in China? A Study Based on Three-party Evolutionary Game Model under Incomplete Information. Sustainability 2019, 11, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, E.L.; Norrin, M.R.; Jeffery, W.T. Neoclassical Realism, the State, and the Foreign Policy; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, D.F. The Brave New Wired World. Foreign Policy 1997, 106, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K. A Study on North Korean Foreign Trade Structure. World Reg. Stud. 1995, 1, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, L.J. The Great North Korean Famine: Famine, Politics, and Foreign Policy. Nav. War Coll. Rev. 2002, 55, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Z.; Xing, H. Food Shortages in the DPRK and Prospects for a Solution. Contemp. Int. Relat. 2013, 2, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J. An Analysis of North Korean Food Problem. Eurasian Obs. 2000, 3, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D. An Review of North Korean Food Problem. Int. Inf. 2007, 12, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Yang, W.; Sun, S. Analysis of the Impact of China’s Hierarchical Medical System and Online Appointment Diagnosis System on the Sustainable Development of Public Health: A Case Study of Shanghai. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.K.; Lee, H.; Sumner, D.A. Assessing the Food Situation in North Korea. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1998, 46, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireson, R. Food Security in North Korea: Designing Realistic Possibilities; The Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Haggard, S.; Noland, M. Famine in North Korea: Markets, Aid, and Reform; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, G.; Yang, W. Evaluating China’s Air Pollution Control Policy with Extended AQI Indicator System: Example of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, W. Total Factor Efficiency Study on China’s Industrial Coal Input and Wastewater Control with Dual Target Variables. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N. Evolution and Assessment of U.S. Food Aid towards DPRK. Chin. J. Am. Stud. 2014, 28, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Taejin, K. North Korea’s Food Demand and Its Cooperation Plan. Korean J. Unific. Econ. 2010, 14, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y. The Food Politics for Supporting North Korea’s Continuation of Regime. Korean J. Unific. Aff. 2012, 24, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S. Causes of Food Shortage in North Korea and Its Impact on North Korean Society. Policy Sci. Stud. 2008, 18, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Amstutz, M.R. International Conflict and Cooperation: An Introduction to World Politics; McGraw-Hill College: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, F.S.; Rochester, J.M. International Relations; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Bureau of Statistics. North Korea Statistics. Available online: http://kosis.kr/bukhan/index.jsp (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- The East-West Center; The National Committee on North Korea. North Korea in the World. Available online: https://www.northkoreaintheworld.org/humanitarian/food-assistance (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Yang, W.; Li, L. Efficiency Evaluation and Policy Analysis of Industrial Wastewater Control in China. Energies 2017, 10, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yang, W.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, G. Analysis of the Air Quality and the Effect of Governance Policies in China’s Pearl River Delta, 2015–2018. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Yang, W. Study on optimization of economic dispatching of electric power system based on Hybrid Intelligent Algorithms (PSO and AFSA). Energy 2019, 183, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, G.; Bell, T.; Cahalan, R.; Moeng, F. Sampling Errors in the Estimation of Empirical Orthogonal Functions. Mon. Weather Rev. 1982, 110, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, L. Energy Efficiency, Ownership Structure, and Sustainable Development: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y. An Analysis of Agricultural Reform in North Korea. Contemp. Asia-Pac. Stud. 2007, 6, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Noland, M. A Nuclear North Korea: Where Do We Go From Here? Straits Times 2006, 10, 11. [Google Scholar]

- World Food Programme of United Nations. Emergency Operation Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: 10757.0—Emergency Assistance to Population Groups Affected by Floods and Rising Food and Fuel Prices; World Food Programme of United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Yang, Y. Research on Air Pollution Control in China: From the Perspective of Quadrilateral Evolutionary Games. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J. A Study on the Changing of North Korea Agricultural Policy and Cooperation. Econ. Stud. Korean Peasant Assoc. 2018, 48, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Quan, Z. An Analysis of Agricultural Reform of DPRK. Dongjiang J. 2016, 33, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Sanger, D.E. Nuclear Pact Broadening, North Korea and U.S. Say. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/03/world/asia/03nkorea.html (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Min, T.J. Food Shortage in North Korea: Humanitarian Aid Versus Policy Objectives. Hum. Rights Br. 1996, 4, 7. [Google Scholar]

- World Food Programme of United Nations. Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/countries/democratic-peoples-republic-korea (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Harrison, S.S. Time to leave Korea? Foreign Aff. 2001, 80, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, L. Analysis of Total Factor Efficiency of Water Resource and Energy in China: A Study Based on DEA-SBM Model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. The North Korean Human Rights Act of 2004. North Korean Rev. 2006, 2, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, E.L.; Woodhouse, E.J. The Policy-Making Process; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Paarlberg, R. Food Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, B. Another Perfect Storm? Predictors of Radical Change in North Korea. Secur. Chall. 2008, 4, 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.; Huang, Y. Achieving Food Security in North Korea. In Promoting International Scientific, Technological and Economic Cooperation in the Korean Peninsula: Enhancing Stability and International Dialogue; Istituto Diplomatico Mario Toscano; The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Rome, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, B. Climate change and the terminal decay of the North Korean regime. In Proceedings of the 3rd Biennial Oceanic Conference on “International Studies”, Brisbane, Australia, 1–4 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Li, L. Efficiency evaluation of industrial waste gas control in China: A study based on data envelopment analysis (DEA) model. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Policy Dilemma: Food Aid to all Enemy State. Int. Stud. Rev. 2005, 345, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Eberstadt, N. Hastening Korean Reunification. Foreign Aff. 1997, 76, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S. North Korea Vows to Keep Nuclear Arms and Fix Economy. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/01/world/asia/north-korea-vows-to-keep-nuclear-arms-and-fix-economy.html (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Pape, R.A. Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work. Int. Secur. 1997, 22, 90–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. A Study on China-DPRK Relations under the Nuclear Shadow; Sinseong Press: Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, L. South Korea’s Nuclear Hedging? Wash. Q. 2018, 41, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.D. Explaining North Korea’s Nuclear Ambitions: Power and Position on the Korean Peninsula. Aust. J. Int. Aff. 2017, 71, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toby, D.; Ariel, L. When Trump Meets Kim Jong Un: A Realistic Option for Negotiating With North Korea. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/03/26/when-trump-meets-kim-jong-un-realistic-option-for-negotiating-with-north-korea-pub-75898 (accessed on 10 March 2020).

| Dove-Hawk Transformation | Hawk-Dove Scores | Hawk-Dove Averages | Grain Yield | Grain Price Rise and Fall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The First Mode | −0.0053 | −0.3323 | −0.0425 | 0.9422 | 0.0071 |

| The Second Mode | 0.0150 | 0.9350 | 0.1153 | 0.3350 | 0.0005 |

| Dove-Hawk Changes | Dove-Hawk Scores | Dove-Hawk Averages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grain Output | −0.48114 *** | −0.52145 ** | −0.36466 * |

| Grain Output Changes | −0.09399 | −0.23279 | −0.41347 ** |

| Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ε | 2664.9635 | 898.3443 | 2.9665 | 0.0067 |

| −0.2073 | 0.0705 | −2.9293 | 0.0073 | |

| −8.9773 | 8.6341 | −1.0397 | 0.3088 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; He, J.; Yuan, G. An Empirical Analysis on DPRK: Will Grain Yield Influence Foreign Policy Tendency? Sustainability 2020, 12, 2711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072711

Zhang C, He J, Yuan G. An Empirical Analysis on DPRK: Will Grain Yield Influence Foreign Policy Tendency? Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072711

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chi, Jun He, and Guanghui Yuan. 2020. "An Empirical Analysis on DPRK: Will Grain Yield Influence Foreign Policy Tendency?" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072711

APA StyleZhang, C., He, J., & Yuan, G. (2020). An Empirical Analysis on DPRK: Will Grain Yield Influence Foreign Policy Tendency? Sustainability, 12(7), 2711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072711