Abstract

In medical travel, previous studies have investigated the factors that influence medical travellers to receive treatment outside the country. However, most of these studies are limited to travel motivations and perceptions of medical services at destinations. The main objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between medical travellers’ perceived risks, travel constraints, and destination image based on medical and non-medical attributes. This is a quantitative study whereby the data was collected from 306 sub-Saharan African medical travellers, who visited India for the treatment. The study found that physical-health risk has a significant negative influence on destination image based on medical attributes. The service quality risk has a negative effect on destination image based on both medical and non-medical attributes, and destination risk has a negative effect on destination image based on medical attributes. The study also found that travel constraints have a negative influence on both medical and non-medical destination image.

1. Introduction

Several countries have benefited from international medical travel in terms of increased GDP, improved healthcare infrastructure, attracting foreign currency, promoting tourism, and, more importantly, checking the brain drain of skilled medical professionals [1,2]. However, the reason behind this phenomenon is the unavailability of certain types of treatments such as bypass surgery, cancer treatment, transplantations, eyecare in a home country, or treatment that is available with low quality or at a very high price. International medical travel is defined as “the citizens of source country travel to foreign destination hospitals with the sole purpose of obtaining necessary medical procedures and treatment”. Many researchers disagree with using the term “medical tourism” for a journey performed solely in search of medical treatment, as the term otherwise mainly defines the phenomenon of north-to-south travel where receiving health and medical care was combined with leisurely activities. Researchers argue that the majority of individuals traveling outside the country for treatment are needy patients who have the sole motivation to receive the required treatment [3,4].

International travel for medical services in the sub-Saharan region of Africa has been growing rapidly in the last decade [5]. Although the specific figures are not available on the number of travelers traveling outside the country for medical needs, general figures can provide a broad picture of the size of international medical travel in sub-Saharan Africa. According to Crush and Chikanda [6], more than 2 million patients mainly from sub-Saharan Africa traveled to South Africa between 2003–2008 at an average of 400,000 per annum. In the year 2010, an average of 3000 Nigerians traveled to India for medical purposes each month, spending around USD 200 million for medical care [5]. In 2016, Africans spent USD 6 billion on receiving medical treatment abroad, in which Nigerians alone spent USD 1 billion [7]. Although most of the travelers visited India on social visas, India issued 18,000 medical visas to Nigerian patients alone in 2012 and received USD 260 million as revenue [8]. Movement of the patients outside the country intensified in East African countries due to the perception of low-quality services at home and less proactive marketing. Based on estimation, 100,000 East Africans travel to India annually due to high cost of treatment in their home country [9].

Sub-Saharan African medical travellers are the largest contributors to the Indian medical travel industry in terms of numbers and revenue [10]. However, despite being the largest group of visitors, Africans face different kinds of problems in India. African visitors faced incidences of harassment and violent attacks while visiting India, which were covered by the world media [11,12,13]. In reaction to the incidences against Africans in India, local newspapers in African countries quoted general public reaction and found that citizens willing to visit India were concerned about the incidences happening in India [14]. In this situation, it has become very significant to understand the travel-related decision-making of sub-Saharan African medical travellers. As sub-Saharan Africans are the largest group of medical travelers to India, ignoring their concerns and issues will be insidious for the Indian medical travel industry. Evidence from the previous studies shows that medical travelers tend to change their preferred destination over a period of time [15]. Although specific reasons were not available, one or the combination of few factors such as deterioration in service quality, increased cost, personal safety and security, uncomfortable journey, and travel documentation could trigger the change in behavior. According to Prakash, Tyagi [10], issues raised by the medical travelers, who visited India, such as hidden cost, food quality, accommodation, and travel documents, need to be taken care of, otherwise India may lose its competitive advantage. The main objective of the study was to identify and analyze the role of different factors in travel decision making which will help managers to understand the future travel behaviour of African medical travellers.

Many researchers [3,16,17] have made calls to understand the decision making of medical travellers by investigating the influential role of different factors. Although few quantitative empirical studies are available in the context of medical travel and travellers behaviour [18,19], these studies were performed on leisure travellers, therefore, it cannot reflect the views of actual medical travellers. In leisure travel, plenty of studies have been undertaken to understand the decision making process of travellers based on the travel motivations, perceived risks, travel constraints, destination image, and visit intention [20,21,22,23]. The studies proved that these variables have a direct and indirect role in the development of perceptions and visit intention among the travellers. This study was in the direction to investigate the role of travel motivations, perceived risks and travel constraints in the formation of destination image and the effect of the two components of destination image, i.e., medical and non-medical on an intention to visit India among the sub-Saharan African medical travellers.

2. Literature Review and Development of Research Hypotheses

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) can predict the behaviour of individuals through attitude and intention. Intention develops through attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control and leads to actual behaviour. Previous studies applied the TPB model to study medical travel [18,19] and investigate the travel behaviour of travellers.

2.1. Perceived Destination Image (Medical and Non-Medical)

Destination image is “the total of ideas, beliefs, and impressions individual possesses about the attributes of destination and or activities available at a destination after processing information from various sources over a time period” [24]. Echtner and Ritchie [25] described the destination image as “an overall imagery picture individual obtains in his mind.”

The literature gives the impression that the attributes of a medical travel destination can be categorised into medical and non-medical. Hospitals providing services to medical travellers publicise their services through websites and media, and potential travellers predominantly refer to these mediums to select their preferred hospital or clinic to receive treatment [26,27]. The main features medical travellers look for are reliability and quality of services and cost. The importance of the cost factor is high in the context of Asian medical travel destinations as the general perception is that the cost will be significantly lower than their home countries. In terms of medical attributes, medical travel destinations emphasise sophistication, advanced technology, cleanliness and efficiency, variety of procedures, low price, accreditation of hospitals, affiliation of doctors, qualified and smart staff, efficiency of different languages, lavishly furnished wards, and testimonials of the patients [28,29,30,31].

The literature also revealed that support services play an important role in attracting medical travellers. Travellers look for proper accommodation, transportation, cleanliness, and personal safety and security [28]. They also look for the opportunity to tour the destination [32]. Many medical travellers prefer Thailand due to the availability of world-class tourism infrastructure and leisure activities [33]. Services for companions such as accommodation, transport service, and food, etc. play a role in creating a favourable image of a destination [29]. For example, India receives travellers mainly from the low-income countries such as neighbouring countries and Africa, and they often have limited options for accommodation and other services like food and transportation. Prakash, Tyagi [10] found that most medical travellers were not satisfied with the accommodation services and taste of food in India.

In travel and tourism literature, perceived image is considered to be the most important factor in the decision-making of travellers. The results of the previous studies indicate that the destination image was a direct antecedent that influences tourists to visit or revisit a destination [34]. If the image of a destination is positive, it will influence travellers to visit and vice-versa. The process of decision-making of medical travellers is based on evaluating various attributes of the destination, and the image that forms in the mind of the travellers about the destination will influence the choice of destination.

2.2. Perceived Travel Risks

Perceived risk reflects the uncertainty regarding possible negative consequences of using a product or service. In consumer behaviour, perceived risk can be defined as ‘the combination of uncertainty plus seriousness of outcome involved and the expectation of loss associated with a purchase that acts as an inhibitor to purchase behaviour’ [35]. In travel behaviour, perceived risk is “the perceived probability that action may expose an individual to danger and can influence travel decisions if the perceived danger is deemed to be beyond an acceptable level” [36].

In medical travel, travellers from the low and middle income countries are generally perceived as being more vulnerable to different kind of risks at the destination due to lack of knowledge, fewer resources, and prejudices in the local population about them [37,38]. In this study, perception of risks was confined to risks faced by the medical travellers at the destination as pre and post-procedure risks of medical travellers from the high-income countries [39,40]. After a thorough review of the literature, the study categorised the perceived risks faced by medical travellers during their visit as physical-health, service quality, and destination risk. The three dimensions are used in the study to investigate the perceived travel risks of medical travellers.

Physical risk refers to the possibility of physical danger or injury detrimental to health, whereas health risk refers to the possibility of becoming sick while travelling or while at the destination [36]. In medical travel, individuals can be exposed to contracting epidemic diseases due to spending days or weeks as an in-patient. Medical travellers can face the risk of contracting severe blood-borne infections such as HIV, hepatitis, etc. due to improper screening and storage of blood [40]. The health risk for the medical travellers receiving organ transplant is even higher due to the ignorance of standard protocol in donor selection at many destination countries [41]. Therefore, the following can be hypothesised:

H1:

Perceived physical-health risks to medical travellers will negatively influence perceived destination image based on medical attributes.

H2:

Perceived physical-health risks to medical travellers will negatively influence perceived destination image based on non-medical attributes.

Service quality risk is always a matter of concern among medical travellers. Medical travellers are concerned about the skills of physicians, nurses, and technicians. Due to this, most hospitals providing services to medical travellers emphasise obtaining accreditation from international bodies such as Joint Commission International (JCI). However, there were many cases when medical travellers faced difficult times due to negligence in the quality of services provided such as unwanted procedures, inflated the cost, and prolonged stay in the hospitals [3,40,42]. Therefore, it can be hypothesised that:

H3:

Perceived service quality risks to medical travellers will negatively influence perceived destination image based on medical attributes.

H4:

Perceived service quality risks to medical travellers will negatively influence perceived destination image based on non-medical attributes.

In relation to destination risk, medical travellers can be subjected to face criminal incidences such as robbery, physical and sexual assaults, and racism-related incidences at the destination. Medical travellers from the low and lower-middle income countries are subjected to higher vulnerability to these kinds of incidences as in many cases they stay at rented houses for long periods due to the complexity of the medical condition and treatment. Studies in leisure travel have found that the perception of travellers on safety and security, service quality, performance, and health risks have a significant negative influence on destination image perception [22,23,43]. In medical travel, perceived risks were strongly associated with attitude [18] and perceived value [19] of the destination and services. Attitude and value are the perceptions based on attributes and characteristics. In this sense, it can be assumed that perceived risks of medical travellers will create a negative perception about the destination attributes. Therefore, it can be hypothesised that:

H5:

Perceived destination risks to medical travellers will negatively influence perceived destination image based on medical attributes.

H6:

Perceived destination risks to medical travellers will negatively influence perceived destination image based on non-medical attributes.

2.3. Travel Constraints

Travel constraints refer to the “factors that inhibit continued travel, cause inability to begin travel, results in the inability to maintain or increase the frequency of travel, and/or lead to negative effects on the quality of travel” [44]. Travel constraints are the key factors that prevent people from initiating or continuing to travel [45].

Although the constraints factor in international medical travel is largely unexplored, the literature indicates that medical travellers face different types of travel constraints such as anxiety, stress, sickness and stage of life, lack of money, travel documents, and travel companion [10,15,46]. Muraina and Tommy [5] found that most Nigerian medical travellers felt stress when travelling abroad for medical needs. Emotional factors also contribute to the constraints faced by medical travellers as in many cases close family members do not travel with the patient and other relatives accompany them while receiving treatment [15]. The constraints related to support services can also be a factor that inhibits international medical travel. According to Prakash, Tyagi [10], most African travellers perform their journey to India via Middle-Eastern countries due to the lack of direct flights. This broken journey could be painful for medical travellers who have severe medical conditions. Structural factors such as flight connectivity, documentation, and visa were major issues associated with medical travellers.

Medical travellers face different types of constraints while planning to travel to a destination. Travel constraints could be specific to a destination which may not be the same for another destination. In this situation, travel constraints will surely affect the perceived image of a destination. The literature in travel and tourism explained the negative effects of constraints on destination image [21,23] and collectively posit that the travel constraints of medical travellers will have a negative effect on the perceived image destination. Therefore, it can be hypothesised that:

H7:

Travel constraints of medical travellers will negatively influence destination image based on medical attributes.

H8:

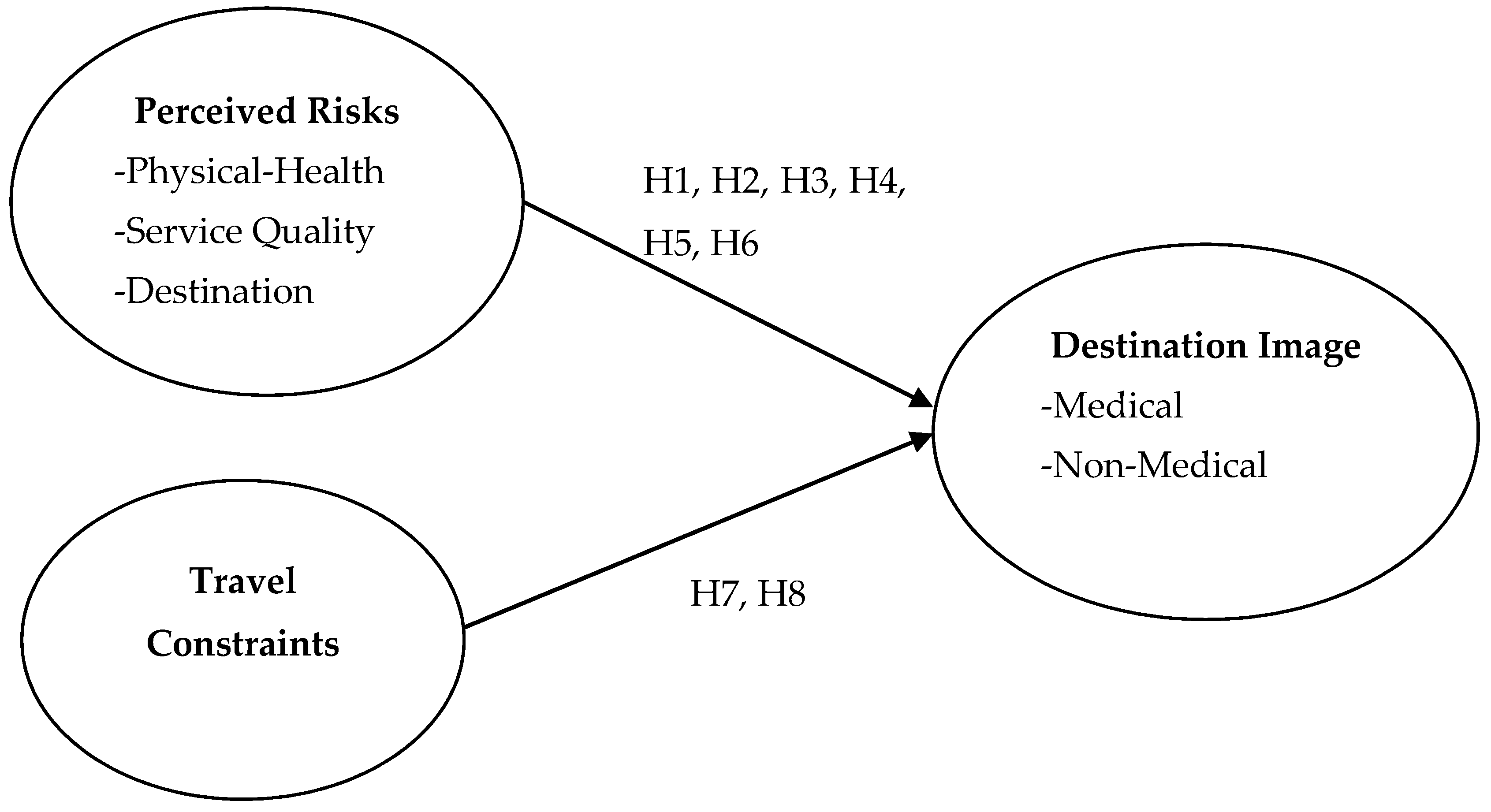

Travel constraints of medical travellers will negatively influence destination image based on non-medical attributes. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection Procedure and Sampling

Data were collected from the sub-Saharan African medical travellers visiting two large private hospitals in Delhi and NCR in the months of February-July 2017. Six medical travel facilitators, officially associated with the hospitals and providing services to medical travellers in the vicinity of the hospitals, were engaged in finding medical travellers to participate in the study survey (see Appendix A). Non-probability convenience sampling was used due to the lack of a sample frame. Convenience sampling is the most frequently used technique in quantitative studies [47]. Pick/drop method was used, and the questionnaires were dropped to the facilitators and collected. In total, 700 questionnaires were distributed, and 318 were returned to the researchers (response rate of 45.4%). All of the returned questionnaires were thoroughly scrutinised, and 306 were found fit for data analysis.

To ensure no common method bias in the questionnaire survey, Harman’s single factor test was performed. The results revealed that the first factor accounted for 20.10% of the variance, which was less than the given threshold level of 50% of the total variance explained [48]. Studies identified that the minimum sample size of 100 is adequate for PLS-SEM [49]. Chin [50] explained the rule of thumb “ten times rule” for PLS-SEM analysis. Statistical power is another way to estimate the more restrictive minimum sample size recommended for PLS-SEM analysis [51]. The sample size of 306 satisfied all the conditions to estimate the minimum sample size.

3.2. Measurement

All the items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale that ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. For physical-health risk, three items; service quality risk, three items; and destination risk, six items were adapted from Fuchs and Reichel [52], Fuchs [53], and Sönmez and Graefe [54], respectively. Five items for travel constraints were adapted from Huang and Hsu [55]. For destination image based on medical attributes, nine items; and non-medical attributes, nine items were adapted from Saiprasert [56]. Pre-testing of the survey questionnaire was conducted using the debriefing method of personal interviews suggested by Hunt, Sparkman Jr. [57].

3.2.1. Data Analysis and Findings

Most of the study respondents were male (73.5%), and most of the respondents were married (66.3%). The study divided the age group into five categories; the age of the respondents was evenly distributed in four groups except for 36–45 years which represented 32.4% of the total respondents. Table 1 details the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Profile of Respondents (N = 306).

3.2.2. Assessment of Measurement Model

The factor loadings of all the items used exceeded the recommended value of 0.708 by Hair, Sarstedt [58] except for nine items. However, these items were retained in the analysis as the average variance extracted (AVE) of the correspondent variables of these items were higher than the recommended value of 0.50. The composite reliability (CR) for the constructs ranged from 0.842-0.959. The values exceeded the cut-off value of 0.70 for CR as recommended by Hair, Sarstedt [58]. Table 2 summarises the loadings, CR, and AVE for the items and constructs.

Table 2.

The Results of Measurement Model and Descriptive Analysis.

The discriminant validity of the model was tested by Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. This study used a conservation level of 0.85 (i.e., HTMT0.85) as suggested by Henseler, Ringle [59]. Table 3 shows that the discriminant validity of the model was established since all the results of the HTMT0.85 criterion were below the critical value of 0.850.

Table 3.

The Results of Discriminant Validity Analysis (HTMT0.85 Criterion).

3.2.3. Assessment of the Structural Model

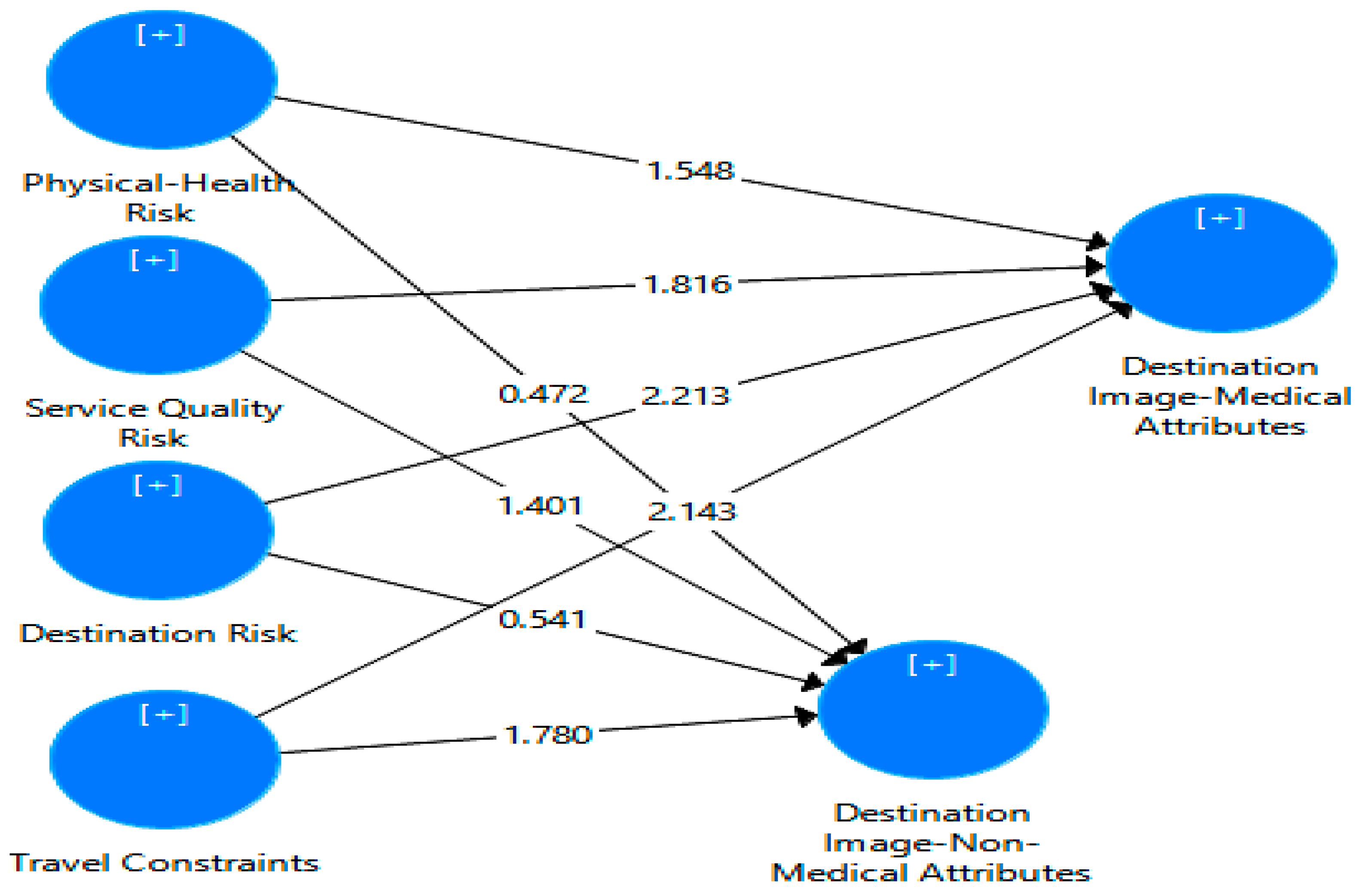

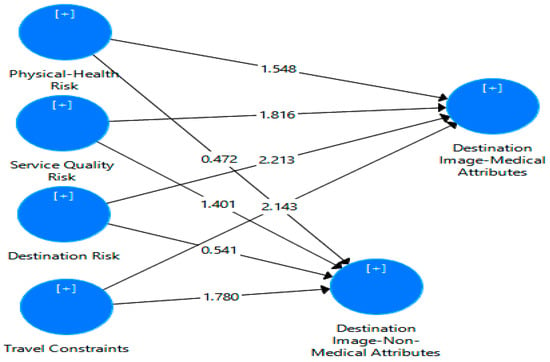

In PLS, the main evaluation criterion for the goodness of the structural model is that the R2 measures the coefficient of determination and the level of significance of the path coefficient [60]. The recommended value [61] of R2 between 0.02 and 0.12 is weak, 0.13 and 0.25 moderate, and 0.26 and above substantial. However, Hair, Ringle [60] qualified these figures and suggested that a high R2 is dependent on specific research context. The R2 of destination image-medical attributes is 0.102 and non-medical attributes 0.083 which shows the percentage of total variance explained of these variables by respective exogenous variables. Figure 2 shows the respective exogenous variables of the two endogenous variables.

Figure 2.

Output of Structural Model Analysis.

The path coefficients were significant for the relationships between travel physical-health risk and destination image-medical attributes (β = −0.139, p < 0.10), service quality risk and destination image-medical and non-medical attributes (β = −0.128, p < 0.05; β = −0.138, P < 0.10 respectively), destination risk and destination image-medical attributes (β = −0.233, p < 0.05), and travel constraints and destination image-medical and non-medical (β = −0.176, p < 0.01; β = −0.186, p < 0.05, respectively). Therefore, H1, H3, H4, H5, H7, and H8 were supported (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Assessment of Structural Model.

The predictive sample reuse technique, also known as the Stone-Geisser’s Q2, can be used as a criterion for predictive relevance in addition to looking at the magnitude of R2 [62]. The Q2 value greater than zero indicates that exogenous variables have predictive relevance for endogenous variables [53]. Table 5 details the values of Q2, GoF, and power. The study conducted global goodness-of-fit (GoF) for the SEM as suggested by Tenenhaus, Amato [63]. Wetzels, Odekerken-Schröder [64] guidelines were followed to estimate the GoF value which can be used as a cut-off for the global validation of the PLS model. The GoF value for the study model of 0.326 exceeded the cut-off value of 0.25 for a moderate effect size of given by Akter and Hani [65]. The power analysis for the study model was done by using the Danielsoper.com [66]. Cohen [61] argued that there is a useful role for power analysis in assessing completed research particularly in which non-significant results were obtained. The result of the power analysis indicates that the regression models hold adequate power (> 0.85), as given by Cohen [61].

Table 5.

Results of Blindfolding, GoF, and Power Analysis.

4. Discussion and Implications

The study found that those medical travellers who perceived high physical-health risks possessed negative perceptions of the destination image based on medical attributes. Physical-health risks were measured based on facing health-related issues, getting sick due to contaminated food and drinking water, and contracting infectious diseases. The image of many medical travel destinations is weak in terms of hygienic conditions, pollution, infectious diseases, physical injuries, and safety and security [3,67,68,69]. The findings of this study support the arguments by researchers on the perception of risks. Many western governments release their travel advisories periodically and warn their citizens about contracting infectious diseases such as malaria, Japanese encephalitis, cholera, typhoid, hepatitis, tuberculosis, and poor air quality, and physical injuries due to accidents while travelling to countries of Asia and Latin America. Most of the well-established medical travel destinations are in this region. Western governments also advise those citizens who have existing medical conditions to take extra care of their health while travelling to emerging countries [70,71,72,73]. The Governments of Canada, America, and the UK have issued special travel advice to medical travellers about health-related issues at medical travel destinations such as blood-borne infections like HIV, hepatitis-B due to infected blood transfusion, acquiring malaria from local blood banks, contact with multi-drug resistant bacteria in hospitals, and illegal organ selling. Although the situation related to the prevalence of infectious diseases, physical injuries, and hygiene is no better in most of the medical travel source countries than the destination countries, a wide range of sources of information such as medical travel blogs, forums, websites, and travel advisories from western governments may create health-related worries in the minds of most medical travellers, especially when they are already suffering serious medical conditions. The medical travel destinations and the hospitals providing services to medical travellers should take initiatives to reduce the physical-health related concerns to increase the confidence of medical travellers. The marketing managers must take initiatives to spread positive images about destinations in terms of safe food and drinking water and about the measures taken for the prevention of infectious diseases and physical injuries to reduce the perception of physical-health risk among medical travellers.

The results also found that the perceived service quality risk among medical travellers was negatively related to the perception of the destination on medical and non-medical attributes. Service quality risk was measured based on unsatisfactory medical service that fails to meet expectations and is not value for money. However, descriptive analysis shows that the mean value of the variable service quality risk was 2.65 (SD = 1.31), which means that most of the respondents consider service quality risk related to medical travel destination as being low. The literature on medical travel argued that the high-quality medical service provided by the hospitals at the medical travel destination is the most important factor that pushes the majority of the medical travellers to travel to foreign country [3,5,6,74]. However, a negative perception of non-medical attributes is a concern for medical travel destinations. The findings of this study support the arguments of previous studies that issues such as hidden cost, food quality, accommodation, and travel documents need to be addressed for the continuous growth of medical travel [10]. Medical travel destinations must emphasise maintaining and improving the quality of medical and non-medical services offered to medical travellers and highlight them in the marketing and promotional materials to attract more medical travellers.

The results of the study reveal that the destination risks of the medical travellers were negatively related to the medical attributes of the destination. Destination risk was measured based on crime and safety, political instability, racist attacks, and prejudice among the local population. Destination risks have not been given due consideration in medical travel literature. However, most medical travel destinations are middle or lower-middle income countries and rank low on the social progress index [75]. Medical travellers face different kinds of crime and safety issues at the destinations such as the sexual assault on female foreign patients at hospitals, fraud, and opposition to medical travel by nationalist groups [76,77,78,79]. The most alarming aspect of the finding is that problems and issues not related to medical services are damaging the image of the destination based on medical attributes. Safety and security, crime, and political unrest are issues that have damaged the tourism industry of many countries. Medical travel destinations should also keep in mind that the medical traveller could be more vulnerable to destination related risks as they reside in one place for long periods to complete the treatment. Medical travel destinations must take these issues seriously and find solutions to tackle them for the continuous arrival of medical travellers.

The findings also revealed that those medical travellers who perceived travel constraints also perceived the destination negatively based on medical and non-medical attributes. The study provides interesting findings on the travel constraints of medical travellers. The perceived travel constraints were measured based on stress and anxiety felt, difficulty to find companion, the arrangement of money, the arrangement of travel documents, and flight connectivity from the home country. As far as anxiety and stress are concerned, managers must identify the factors which lead to stress and anxiety among medical travellers. More positive information should be spread among potential medical travellers about the medical and support services that will lead to a reduction in stress Managers also need to identify the issues and problems faced by travellers and work on reducing and correcting those problems so that negative word of mouth can be reduced. For the issue of finding a companion, the destination should develop a supporting mechanism that minimises the need of having a companion. Kangas [15] found that finding a suitable companion to travel abroad was a difficult task for medical travellers. She found that the head of the household who was also the earning member of the family and main decision-maker could not accompany the patient due to work commitments and arrangements of money to finance the trip. Therefore, travellers need a companion to travel with them who can take necessary decisions if needed while the patient receives treatment [80]. Destinations must develop a mechanism that can reduce the need to take crucial decisions by the patient at the time of receiving treatment. Detailed communication before arrival between the hospital and the patients about the procedure, treatment, expenses, and other support services will reduce the need for taking spontaneous decisions at the destination.

Studies of medical travellers have found that the arrangement of medical travel documents and flight connectivity from many source countries is a major issue faced by medical travellers [3,10]. Due to the tedious process which requires a lot of paperwork, most medical travellers visit the destination countries on tourist visas which can sometimes complicate their treatment. A tourist visa allows visitors to stay for a shorter period (in some cases for 15 days only), and sometimes medical procedures force travellers to stay for longer periods. In this case, receiving a further extension of the visa gives can be troublesome, especially when patients are undergoing treatment. For example, the Government of India recently took measures to provide e-visa to health travellers from more than 150 countries [81,82]. However, this relaxation does not include those who want to travel to receive medical treatment. Flight connectivity from many source countries such as the sub-Saharan region is another issue to which governments must take care to attract more medical travellers from this region.

The findings suggest that medical travel destinations should also focus on the risk perceptions and travel constraints of medical travellers instead of just promoting medical services to international patients. It is true that the main criterion for selecting a destination by foreign patients is the quality and cost of medical services. However, at present, many countries are developing their healthcare infrastructure to attract foreign patients by providing quality medical care at low cost and the criterion to choose a destination will include factors such as vulnerability to different kind of risks and ease of travel. Destination marketing managers should develop their marketing strategies that provide solutions to risk perceptions and travel constraints of medical travellers. At the same time, destinations must develop policies and measures that reduce the possibility of getting harmed at the destination for medical travellers.

5. Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Recommendations

The study contributes to the body of knowledge in two ways. First, the study was performed on actual international medical travellers, as most of the previous quantitative empirical studies [19,20] were performed on potential medical travellers. Therefore, this study provides useful insight into the travel behaviour of actual medical travellers. Second, the study conceptualised and integrated different factors in a single framework that are crucial in the travel decision-making of medical travellers and empirically tested their relationships. Based on the path coefficient values, it was found that physical-health risk (β = −0.139, p < 0.10), service quality risk (β = −0.128, p < 0.05), and destination risk (β = −0.233, p < 0.05) had negative relationship with destination image based on medical attributes, whereas, service quality risk was negatively associated (β = −0.138, p < 0.10) with destination image based on non-medical attributes also. Travel constraints were negatively associated with both destination images based on medical and non-medical attributes. It was found that physical-health risk and destination risk have no relationship with destination image based on non-medical attributes. The empirical evidence of the study suggests that perceived risks and travel constraints of medical travellers negatively affect their perception about the destination on different aspects such as quality of medical services, quality of support services, culture, physicians’ skills, medical facilities, etc. and influence their travel behaviour. The destination and hospitals providing services to foreign patients must understand the perceptions of medical travellers. The study suggests that destinations and hospitals should be aware of the types of risks and constraints medical travellers face so that their future behaviour can be understood better.

Although the study has considerable practical implications, the study has several limitations. The study was performed on sub-Saharan African medical travellers visiting India. Therefore, care should be given in generalising the study findings to medical travellers from other regions. The study used non-probability convenience sampling due to the lack of a sample frame which limits the generalisability of the study findings. The study sample was skewed toward male respondents. 73.5% of the study respondents were male which means that the findings of the study could be biased towards male medical travellers. Future studies could be performed on medical travellers travelling from other parts of the world, and the findings can be compared to develop a better understanding of the travel behaviour of medical travellers. As this study could not provide equal representation of female medical travellers, future studies can use a more balanced sample of male and female participants so that the results can be generalised for both genders. Future studies can be performed on the different decision-making stages of international medical travel to examine if information sources and other personal factors play a role in the perception of risks and constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.K. and F.K.; methodology, M.J.K, F.K. and S.A.; software, M.J.K.; validation, S.C.; formal analysis, M.J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.K., F.K., and S.A.; writing—review and editing, S.C.; supervision, S.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Survey Items

Table A1.

Survey Items

| PERCEIVED TRAVEL RISKS | |

| Physical-Health Risks | |

| 1 | I was worried about health-related problems in India |

| 2 | I was worried about getting sick due to food or drinking water in India |

| 3 | I was worried about the possibility of contracting infectious diseases in India |

| Service Quality Risks | |

| 1 | I was worried about that the quality of medical services in India may not meet my expectations |

| 2 | I was worried that quality of medical services in India may not provide satisfactory result |

| 3 | I was worried that medical services in India will not provide value for money |

| Destination Risks | |

| 1 | I was worried about potential violent attacks in India |

| 2 | I was worried about exposed to crime in India |

| 3 | I was worried about political instability in India that could keep me away from receiving my treatment |

| 4 | I was worried about facing racist attack/abuse in India |

| 5 | I was worried about difficulty in finding suitable accommodation in India |

| 6 | I was worried about being prejudiced by local people in India |

| TRAVEL CONSTRAINTS | |

| 1 | The thought of taking treatment in India filled me with anxiety |

| 2 | It was difficult for me to find companion to travel to India |

| 3 | Visiting India for treatment need a lot of money |

| 4 | Getting travel document for treatment in India was not easy |

| 5 | Flight connectivity from my home country to India was not good |

| PERCEIVED DESTINATION IMAGE | |

| Medical Services | |

| 1 | India offer medical services at reasonable price |

| 2 | Taking medical services in India cause significant amount of money savings |

| 3 | Indian medical facilities are recognized as modern and up-to-date |

| 4 | Indian hospitals service quality is accredited by international accreditation bodies (such as JCI, ISO etc.) |

| 5 | Indian hospitals offer high quality of medical services with latest technology |

| 6 | Indian doctors are highly skilled and well trained |

| 7 | Indian medical staff (such as nurses, technicians, etc.) are highly skilled and well trained |

| 8 | India offer medical treatments for different kind of diseases |

| 9 | Indian hospitals offer good services after procedure (such as providing proper medication and follow-up checkups, etc.) |

| Non-Medical Service | |

| 1 | India offer easy medical visa services and immigration procedures for medical travelers |

| 2 | Indian people are friendly and helpful |

| 3 | No language barriers in traveling to India for medical services |

| 4 | Local transportation in India are easily available and convenient |

| 5 | Accommodation in India for patient and companion is easily available and convenient |

| 6 | India offer adequate safety from crime and terrorist attack |

| 7 | India offer highly stable political environment |

| 8 | India has good reputation as tourism destination |

| 9 | India offer different activities for relaxation after medical treatment |

References

- Ramirez, D.A.A.B. Patients without borders: The emergence of medical tourism. Int. J. Public Health 2007, 2, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Purdy, L.; Fam, M. Evolving medical tourism in Canada: Exploring a new frontier. In Deloitte Center for Health Solutions; Deloitte: Quebec, Canada, 2011; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, J. Contemporary medical tourism: Conceptualisation, culture and commodification. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Haron, M.S. Push factors, risks, and types of visit intentions of international medical travelers–a conceptual model. J. Healthc. Manag. 2017, 10, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraina, L.; Tommy, I. Outbound Medical Tourism: Result of a Poor Healthcare System. Available online: http://www.ciuci.us/outbound-medical-tourism-result-of-a-poor-healthcare-system- (accessed on 3 August 2015).

- Crush, J.; Chikanda, A. South–South medical tourism and the quest for health in Southern Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 124, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedong, T.A. African Politicians Seeking Medical Help Abroad is Shameful, and Harms Health Care, 2017. Available online: https://theconversation.com/african-politicians-seeking-medical-help-abroad-is-shameful-and-harms-health-care-82771 (accessed on 19 May 2018).

- Abimbola, S. Using the High-End Health Market for Regional Integration in Africa. Available online: http://www.afdb.org/en/blogs/integrating-africa/post/using-the-high-end-health-market-for-regional-integration-in-africa-12998/ (accessed on 9 June 2015).

- Mwijuke, G. Rising Medical Bills Sending East African Patients Abroad. Available online: http://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/news/Rising-medical-bills-sending-East-African-patients-abroad/-/2558/2723450/-/139ke5gz/-/index.html (accessed on 9 June 2015).

- Prakash, M.; Tyagi, N.; Devrath, R. A study of the Problems and Challenges Faced by Medical Tourists Visiting India 2011; Indian Institute of Tourism and Travel Management: Delhi, Indian, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jazeera, A.L. Crowds Attack Africans in India after Teen’s Death; Al Jazeera: New Delhi, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Independent. Africans being attacked by roaming mobs in India; Independent: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times. Attacks against African Students Rise in India, Rights Advocates Say. The New York Times, 29 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, P. Murder Of Nigerian In Goa Uncovers Ugly Racialist Attitudes Of Indians Against Black Africans. International Business Time. 6 November 2013. Available online: http://www.ibtimes.com/murder-nigerian-goa-uncovers-ugly-racialist-attitudes-indians-against-black-africans-1458578 (accessed on 21 August 2015).

- Kangas, B. Traveling for medical care in a global world. Med. Anthropol. 2010, 29, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanefeld, J.; Lunt, N.; Smith, R.; Horsfall, D. Why do medical tourists travel to where they do? The role of networks in determining medical travel. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 124, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Haron, M.S.; Ahmed, S. Role of Travel Motivations, Perceived Risks and Travel Constraints on Destination Image and Visit Intention in Medical Tourism: Theoretical model. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2017, 17, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na Seow, A.; Choong, Y.O.; Moorthy, K.; Chan, L.M. Intention to visit Malaysia for medical tourism using the antecedents of Theory of Planned Behaviour: A predictive model. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y. Value as a medical tourism driver. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2012, 22, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloğlu, Ş.; McCleary, K.W. U.S. International Pleasure Travelers’ Images of Four Mediterranean Destinations: A Comparison of Visitors and Nonvisitors. J. Travel Res. 1999, 38, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Chen, P.-J.; Okumus, F. The relationship between travel constraints and destination image: A case study of Brunei. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H.; Lane, C. Image and perceived risk: A study of Uganda and its official tourism website. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Ahmed, S. Factors influencing destination image and visit intention among young women travellers: Role of travel motivation, perceived risks, and travel constraints. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographical Location Upon That Image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.B. The Measurement of Destination Image: An Empirical Assessment. J. Travel Res. 1993, 31, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghavvemi, S.; Ormond, M.; Musa, G.; Isa, C.R.M.; Thirumoorthi, T.; Bin Mustapha, M.Z.; Kanapathy, K.; Chandy, J.J.C. Connecting with prospective medical tourists online: A cross-sectional analysis of private hospital websites promoting medical tourism in India, Malaysia and Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, N.; Carrera, P. Medical tourism: Assessing the evidence on treatment abroad. Maturitas 2010, 66, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junio, M.M.V.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, T.J. Competitiveness attributes of a medical tourism destination: The case of South Korea with importance-performance analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 34, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Musa, G.; Thirumoorthi, T.; Doshi, D. Travel behaviour among inbound medical tourists in Kuala Lumpur. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasoontorn, R.; Zee, R.B.; Sivayathorn, A. Service quality as a key driver of medical tourism: The case of Bumrungrad International Hospital in Thailand. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2011, 2, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkit, M.; McKercher, B. Desired Attributes of Medical Treatment and Medical Service Providers: A Case Study of Medical Tourism in Thailand. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 33, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimehfar, F.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Decisive factors in medical tourism destination choice: A case study of Isfahan, Iran and fertility treatments. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enteen, J.B. Transitioning online: Cosmetic surgery tourism in Thailand. Telev. New Media 2014, 15, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, J.E.; Sanchez, M.I.; Sanchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. Int. J. Human-Computer Stud. 2003, 59, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 112–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormond, M. En route: Transport and embodiment in international medical travel journeys between Indonesia and Malaysia. Mobilities 2013, 10, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L. News media reports of patient deaths following ‘medical tourism’for cosmetic surgery and bariatric surgery. World Bioeth. 2012, 12, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, V.A.; Kingsbury, P.; Snyder, J.; Johnston, R. What is known about the patient’s experience of medical tourism? A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, V.A.; Whitmore, R.; Snyder, J.; Turner, L. “Ensure that you are well aware of the risks you are taking…”: Actions and activities medical tourists’ informal caregivers can undertake to protect their health and safety. BMC Public Heal. 2017, 17, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Lunt, N.; Carrera, P. Systematic review of web sites for prospective medical tourists. Tour. Rev. 2011, 66, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.; Crooks, V.A.; Snyder, J. I didn’t even know what I was looking for”: A qualitative study of the decision-making processes of Canadian medical tourists. Glob. Heal. 2012, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Petrick, J.F. Developing a measurement scale for constraints to cruising. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 206–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstetter, D.L.; Yen, I.-Y.; Yarnal, C.M. Plowing uncharted waters: A study of perceived constraints to cruise travel. Tour. Anal. 2005, 10, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, B. Therapeutic itineraries in a global world: Yemenis and their search for biomedical treatment abroad. Med Anthr. 2002, 21, 35–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suen, L.-J.W.; Huang, H.-M.; Lee, H.-H. A comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Hu Li Za Zhi 2014, 61, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of partial least squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. Tourist destination risk perception: The case of Israel. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2006, 14, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G. Low Versus High Sensation-seeking Tourists: A Study of Backpackers’ Experience Risk Perception. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 15, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H. Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiprasert, W. Examination of the Medical Tourists Motivational Behavior and Perception: A Structural Model; Oklahoma State University: Stillwater, OK, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.D.; Sparkman Jr, R.D.; Wilcox, J.B. The pretest in survey research: Issues and preliminary findings. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Amato, S.; Esposito Vinzi, V. A global goodness-of-fit index for PLS structural equation modelling. In Proceedings of the XLII SIS Scientific Meeting, Padova, Italy, 1 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Hani, U. Complex modeling in marketing using component based SEM. In Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference (ANZMAC2011), Perth, Western Australia, 2 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsoper.com. Free Statistical Calculators, 2016. Available online: http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/default.aspx (accessed on 25 December 2016).

- Bookman, M. Medical Tourism in Developing Countries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- NaRanong, A.; NaRanong, V. The effects of medical tourism: Thailand’s experience. Bull. World Heal. Organ. 2011, 89, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlowe, J.; Sullivan, P. Medical tourism: The ultimate outsourcing. People Strategy 2007, 30, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Travel.State.Gov. Country Information-India, 2017. Available online: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/international-travel/International-Travel-Country-Information-Pages/India.html (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- Government of Canada. Receiving Medical Care in Other Countries, 2017. Available online: https://travel.gc.ca/travelling/health-safety/care-abroad (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- Australian Government. India-Official Advice: High Degree of Caution, 2017. Available online: http://smartraveller.gov.au/Countries/asia/south/Pages/india.aspx (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- GOV.UK. Foreign Travel Advice- India, 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/india/health (accessed on 30 December 2017).

- Ormond, M.; Sulianti, D. More than medical tourism: Lessons from Indonesia and Malaysia on South–South intra-regional medical travel. Curr. Issues Tour 2017, 20, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Stern, S.; Green, M. Social Progress Index 2017; Social Progress Imperative: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis, D. American Student Molested by Physician at Indraprastha Apollo Hospital in New Delhi. The American Bazaar. 23 June 2014. Available online: http://www.americanbazaaronline.com/2014/06/23/american-student-molested-physician-indraprastha-apollo-hospital-new-delhi/ (accessed on 21 August 2015).

- The Times of India. Hospital Staffer Sexually Assaults Afghan Woman Attending to Mom. The Times of India. 2 August 2015. Available online: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/Hospital-staffer-sexually-assaults-Afghan-woman-attending-to-mom/articleshow/48313490.cms (accessed on 21 August 2015).

- Goldbach, A.R.; West, D.J., Jr. Medical tourism: A new venue of healthcare. J. Glob. Bus. Issues 2010, 4, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Tribune. Medical Tourism Dips Due to Mismanagement. Financial Tribune. 26 December 2017. Available online: https://financialtribune.com/articles/travel/78692/medical-tourism-dips-due-to-mismanagement (accessed on 29 August 2015).

- Casey, V.; Crooks, V.A.; Snyder, J.; Turner, L. Knowledge brokers, companions, and navigators: A qualitative examination of informal caregivers’ roles in medical tourism. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S. New Policy on the Cards to Boost Medical Tourism; The Times of India: Mumbai, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IMTJ. New Rules for Medical and Health Tourism E-Visas to India. 2016. Available online: https://www.imtj.com/news/new-rules-medical-and-health-tourism-e-visas-india/ (accessed on 3 January 2018).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).