Local Planning Practice towards Resilience: Insights from the Adaptive Co-Management and Design of a Mediterranean Wetland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- The need for a non-equilibrium and evolutionary approach;

- (2)

- The need for an adaptive co-management and design approach;

- (3)

- The crucial role played by green infrastructures and nature-based solutions;

- (4)

- The contribution made from case studies to elucidate the complex processes involved in resilience implementation within planning practice, with special attention to the local scale.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Territorial, Urban and Planning Context of the Case Study

- Small wetland: The Charca de Suárez area is just 14 ha. Small wetlands tend to be overlooked, and there are few works which analyse their specificities. Being small normally implies that there is no exploitation of wetland products (agriculture/aquaculture), as it is the case of the Charca. Manuel [28] states that it is quite easy to appreciate the different values of large and productive wetlands, but “it is quite another matter to understand the value of a small, reedy, pond tucked between a shopping mall parking lot and a row of well-manicured suburban backyards”. It is not by chance that the existing guidelines and good practices are more commonly found for extensive wetlands.

- Isolated wetland: Although the Charca de Suárez was once a part of the Guadalfeo’s Wetlands, now it is an isolated wetland, the only one in the Province of Granada. That prevents the regional approach that is normally agreed to be an optimal scale for wetland management [29,30]. Nevertheless, its isolated nature and the adverse conditions the Charca has gone through (see following paragraphs) have constituted the “crisis or changing context” from which the adaptive co-management normally emerges [31].

- Urban wetland: As mentioned in the introduction, the Charca is an urban wetland. Being urban also implies a specific reference domain separate from non-urban wetlands [32]. Even if the existing global wetlands policy directives are less optimal for effective governance in the case of urban wetlands [33], urban wetlands may be considered smart, cost-effective tools for urban designers and planners to be used in urban areas [34].

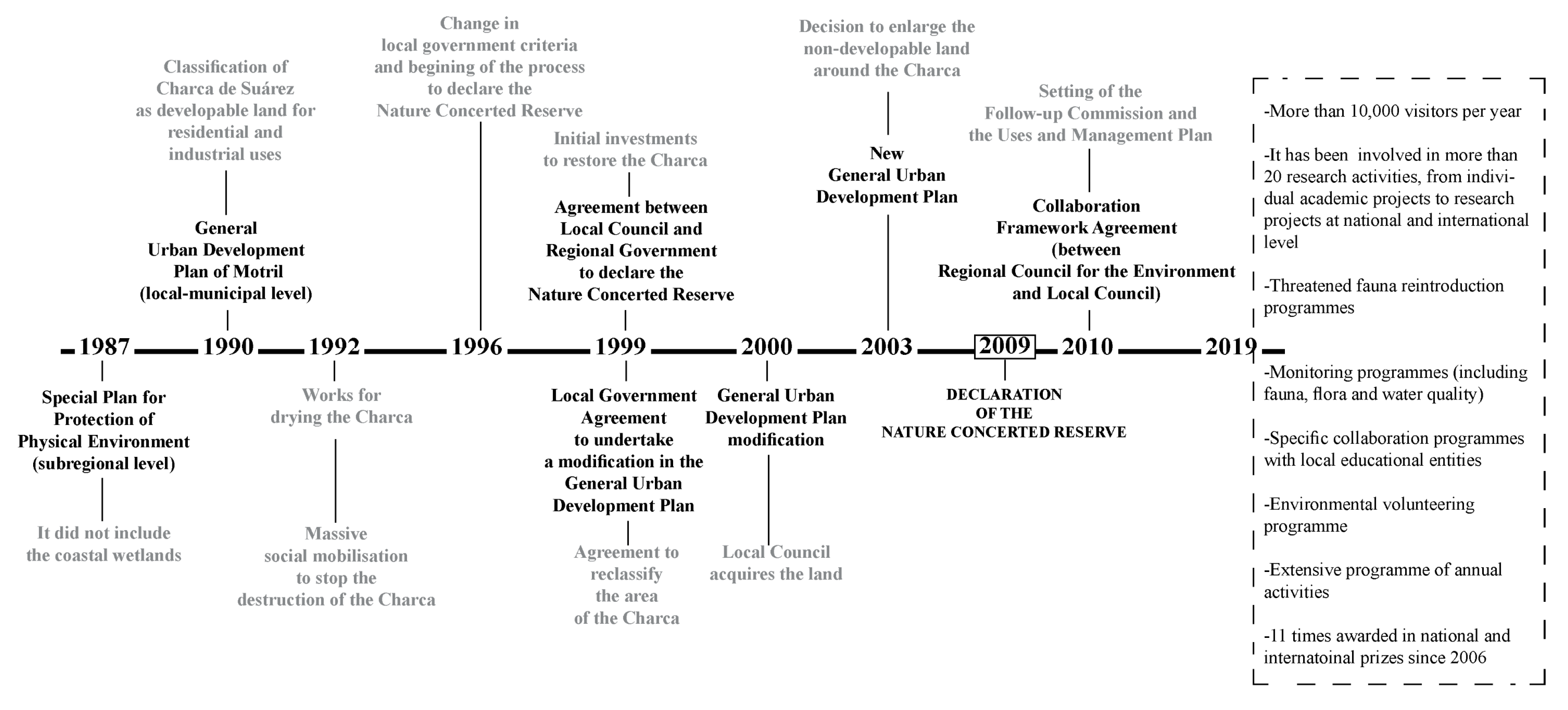

- A change in the Spanish policies that define the use and management of wetlands in the late eighties. According to Sebastià-Frasquet et al. [29], the period of 1950–1980 was characterized by plans promoting the filling and draining of wetlands for agricultural use, but with the incorporation of Spain to the European Union in 1986, there was a shift in these policies towards the inclusion of restoration and protection of wetlands. Nevertheless, the echoes of this first period maybe explain why the Special Plan for the Protection of the Physical Environment did not include coastal wetlands;

- The approval of the Law on Protected Natural Spaces of Andalusia in 1989, which contains the novel figure of Nature Concerted Reserve. This figure opened a possibility for the Charca de Suárez that was immediately explored by the actors involved in the Charca project;

- The start of draining works of the Charca in 1992, which triggered a massive social response that was accompanied by an awareness campaign conducted by Buxus Ecologist Association (Asociación Buxus de Ecologistas en Acción), an environmental non-governmental organization.

2.2. A framework for Reading the Charca Experience in a Resilience Perspective

- The Charca de Suárez website (Local Council of Motril);

- The Visitor’s Window to Protected Natural Spaces;

- The Uses and Management Plan of the Charca (available at the Local Council of Motril);

- Interviews with representatives of the Buxus Environmental Association and the Environment Area of the Local Council of Motril. The interviews implied questions mainly concerning management and planning policies adopted in the Charca and governance aspects (the Charca collaborative and supportive network, in particular, see Section 3);

- Field visits organized in different seasons between 2018 and 2019 to check landscape evolution and species’ dynamic.

- Multifunctionality. It implies how urban planning may contribute to providing multiple ecosystem functions in urban lands [39].

- Redundancy and modularization. A modular and decentralized approach to avoid putting “all your eggs in one basket” [9].

- Bio and social diversity. Both types of diversity are closely related to social-ecological systems. The more different biological and social groups we found in a system, the better, since all together may provide a wider range of responses to the changing conditions of the environment.

- Multi-scale networks and connectivity. Urban landscapes should be understood as multi-scale network systems that perform different functions thanks to their connectivity [3].

- Adaptive planning and design. It implies the performance of planning and design in a context of uncertainty and incomplete knowledge [39].

- Understanding the system. It includes, as key aspects: Active observation, accessible information, identification of drivers of change, and broader value systems.

- Operating within the system. It includes, as key aspects: less-hierarchical approaches, collaborative and supportive networks, build community capital, and incremental and experimental approach.

- Efficient resource management. It includes, as key aspects: Build local awareness; connect resources, people, and places, use what exists optimally, and design for change.

- What strategies are adopted?

- How are the adaptive co-management and design strategies performing?

- What bottlenecks are preventing the full compliance of the adaptive co-management and design strategies?

- What aspects of the case study may be considered as a planning innovation?

3. Results

- Multifunctionality. The role of wetlands has been widely studied in terms of the provision of diverse ecosystem services. With specific reference to the Charca, some works highlight the high multifunctionality of the agro-urban landscape where the Charca is located (see References [36,40]); and how the own Charca contributes to the eco-structure of the area [41].

- Redundancy and modularization. In a context of extensive urbanization of coastal areas in Andalucía and especially along with the Coast of Granada, the Charca project, that rejects the possibility of urbanizing one of the last residual open areas, contributes to avoiding putting “all the eggs in one basket”. This strategy is also adopted inside the Charca project itself. The acknowledgement of the project as an experiment of continuous learning is the main argument behind the creation of three ponds in the area. Not all the experiential management tasks are undertaken simultaneously in the three ponds, but just in one of them that acts as an experimental pond, while the other two remain as control ponds.

- Bio and social diversity. The Charca is an example of biodiversity hotspot at the regional and national level. Biological diversity is fostered in the area through the recreation of different habitats that have been successful in attracting new and previously disappeared species. The Charca also aims at increasing social diversity; this objective has been specifically targeted through social inclusion programs to foster participation and accessibility.

- Multi-scale networks and connectivity. The Charca contributes to the overall physical and biological connectivity of the landscape. Due to its location, the Charca connects agricultural areas to beach areas and the sea.

- Adaptive planning and design. The Charca puts in place an adaptive planning and design approach to foster flexible management of natural resources.

3.1. Understanding the System (Active Observation, Accessible Information, Identification of Drivers of Change, and Broader Value Systems)

3.2. Operating within the System (Less-hierarchical Approach; Collaborative and Supportive Networks; Build Community Capital; Incremental and Experimental Approach)

- (a)

- Local level: Three of the six members of the follow-up commission work at the local level organizing the collaborative and supportive network in the area. This part of the network is mainly composed of local people who organize around the open annual volunteering program that is coordinated by the environmental association Buxus and the Local Council of Motril. The network also includes schools and secondary schools that develop specific environmental education activities. Tourism boards both at the local and sub-regional level are also present. The University of Granada plays an important role, by offering direct advice and receiving information from other components of the network that is included in research projects of varied nature.

- (b)

- Regional and national levels: The other three members of the follow-up commission are nodes that connect the project at regional and national levels. This part of the network moves on the spheres of regional spatial planning and regional-national nature conservation. The Charca is included as an Environmental Protection Zone in the Sub-regional Plan of the Costa Tropical de Granada. It is also part of the RENPA (Andalusian Network of Protected Natural Spaces) and has been included in the Spanish Inventory of Wetlands. The network at regional and national levels includes universities from other parts of the Andalusian region together with the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC). These institutions are developing monitoring projects, especially concerning fauna and flora of the wetland.

3.3. Efficient Resource Management (Build Local Awareness; Connect Resources, People, and Places; Use What Exists Optimally; Design for Change)

4. Discussion

- What strategies are adopted?

- How are the adaptive co-management strategies performing?

- What bottlenecks are preventing the full compliance of the adaptive co-management and design approach?

- What aspects of the case study may be considered a planning innovation?

4.1. What Strategies are Adopted?

4.2. How are the Adaptive Co-Management Strategies Performing?

4.3. What Bottlenecks are Preventing the Full Compliance of the Adaptive Co-Management and Design Approach?

4.4. What Aspects of the Case Study May be Considered a Planning Innovation?

5. Conclusions

- In the short term: Light and sound pollution of urbanizations, the arrival of exotic garden plants, the pressure of exotic fauna, domestic fauna (especially cats and feral dogs), water pollution from uncontrolled dumping of the adjacent industrial area, contaminated water entering during the rains, and lack of budget allocation.

- In the medium term: Urban development, especially the proposal for the construction of a marina that would induce the entry of brackish water near the Charca and may cause a decrease in piezometric levels. That would also isolate the Charca area to the west. A proposal for piping the traditional irrigation ditches, which will reduce the contributions to the aquifer (by more than a third) and make disappear hundreds of water channels that constitute the connection routes of the wetland with its environment.

- In the long term: Climate change. Climate change scenarios provided by the Andalusian Regional Council for the Environment indicate an increase in the sea level that will have at least two effects: Salt wedge advance and beach erosion. Changes in evapotranspiration, water availability and the arrival of exotic plants and fauna may also occur.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D.; Coaffee, J. The Routledge Handbook of International Resilience; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzo, B. Problematizing resilience: Implications for planning theory and practice. Cities 2015, 43, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J. From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Botkin, D.B. Discordant Harmonies: A New Ecology for the Twenty-first Century; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Grove, J.M. Resilient cities: Meaning, models, and metaphor for integrating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning realms. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.H.; Salt, D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World, 1st ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C. Resilience and the Cultural Landscape: Understanding and Managing Change in Human-shaped Environments; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, J. Planning for Resilient and Sustainable Cities. In Water Centric Sustainable Communities: Planning, Retrofitting, and Building the Next Urban Environment; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 539–593. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi, S.; Shaw, K.; Haider, L.J.; Quinlan, A.E.; Peterson, G.D.; Wilkinson, C.; Fünfgeld, H.; McEvoy, D.; Porter, L.; Davoudi, S. Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead End? “Reframing” Resilience: Challenges for Planning Theory and Practice Interacting Traps: Resilience Assessment of a Pasture Management System in Northern Afghanistan Urban Resilience: What Does it Mean in Planning Practice? Resilience as a Useful Concept for Climate Change Adaptation? The Politics of Resilience for Planning: A Cautionary Note: Edited by Simin Davoudi and Libby Porter. Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, M.J.; Nedović-Budić, Z.; Aerts, J.; Connop, S.; Foley, D.; Foley, K.; Newport, D.; McQuaid, S.; Slaev, A.; Verburg, P. Transitioning to resilience and sustainability in urban communities. Cities 2013, 32, S21–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davoudi, S.; Brooks, E.; Mehmood, A. Evolutionary Resilience and Strategies for Climate Adaptation. Plan. Pract. Res. 2013, 28, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plummer, R.; Baird, J. Adaptive Co-Management for Climate Change Adaptation: Considerations for the Barents Region. Sustainability 2013, 5, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilkinson, C. Social-ecological resilience: Insights and issues for planning theory. Plan. Theory 2012, 11, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Crona, B.; Armitage, D.R.; Olsson, P.; Tengö, M.; Yudina, O. Adaptive Comanagement: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.; Sullivan, C.; Palm, C.; Huynh, U.; Diru, W.; Masira, J. Monitoring and evaluation to support adaptive co-management: Lessons learned from the Millennium Villages Project. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, D. The Era of Management Is Over. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani, Z.; Sposito, V.; Faggian, R. Maximising the Value of Natural Capital in a Changing Climate Through the Integration of Blue-Green Infrastructure. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2020, 8, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, J.; Doyon, A. Building urban resilience with nature-based solutions: How can urban planning contribute? Cities 2019, 95, 102483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abson, D.J.; von Wehrden, H.; Baumgärtner, S.; Fischer, J.; Hanspach, J.; Härdtle, W.; Heinrichs, H.; Klein, A.M.; Lang, D.J.; Martens, P.; et al. Ecosystem services as a boundary object for sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 103, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, P.R.; Foley, K.; Collier, M.J. Operationalizing urban resilience through a framework for adaptive co-management and design: Five experiments in urban planning practice and policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, C.J.; Holling, C.S. Large-Scale Management Experiments and Learning by Doing. Ecology 1990, 71, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J.; Therrien, M.-C.; Chelleri, L.; Henstra, D.; Aldrich, D.P.; Mitchell, C.L.; Tsenkova, S.; Rigaud, É.; the participants. Urban resilience implementation: A policy challenge and research agenda for the 21st century. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2018, 26, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziervogel, G.; Pelling, M.; Cartwright, A.; Chu, E.; Deshpande, T.; Harris, L.; Hyams, K.; Kaunda, J.; Klaus, B.; Michael, K.; et al. Inserting rights and justice into urban resilience: A focus on everyday risk. Environ. Urban. 2017, 29, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedmann, J. Toward a Non-Euclidian Mode of Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1993, 59, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Ahern, J. ‘Learning by doing’: Adaptive planning as a strategy to address uncertainty in planning. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2008, 51, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darchen, S.; Searle, G. Seoul, South Korea: Dismantling a highway–Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project. In Global Planning Innovations for Urban Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel, P.M. Cultural perceptions of small urban wetlands: Cases from the Halifax Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia, Canada. Wetlands 2003, 23, 921–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiá-Frasquet, M.-T.; Altur, V.; Sanchis, J.-A. Wetland Planning: Current Problems and Environmental Management Proposals at Supra-Municipal Scale (Spanish Mediterranean Coast). Water 2014, 6, 620–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wardekker, J.A.; Wildschut, D.; Stemberger, S.; van der Sluijs, J.P. Screening regional management options for their impact on climate resilience: An approach and case study in the Venen-Vechtstreek wetlands in the Netherlands. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ehrhart, S.; Schraml, U. Adaptive co-management of conservation conflicts—An interactional experiment in the context of German national parks. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ehrenfeld, J.G. Evaluating wetlands within an urban context. Urban Ecosyst. 2000, 4, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, M.; McALPINE, C.; Morrison, T.H. Governing the urban wetlands: A multiple case-study of policy, institutions and reference points. Environ. Conserv. 2014, 41, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, J.D. Can urban agriculture usefully improve food resilience? Insights from a linear programming approach. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2015, 5, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontana, J. El clima de la Costa del Sol de Granada. Aplicaciones Socio-económicas; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Campaña, R.; Valenzuela-Montes, L.M. Agro-urban open space as a component of agricultural multifunctionality. J. Land Use Sci. 2014, 9, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarán-Ruiz, A. La Valoración Ambiental-territorial de las Agriculturas de Regadío en el Litoral Mediterráneo: El Caso de Granada; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Hahn, T. Social-Ecological Transformation for Ecosystem Management: The Development of Adaptive Co-management of a Wetland Landscape in Southern Sweden. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, art2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J. Urban landscape sustainability and resilience: The promise and challenges of integrating ecology with urban planning and design. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela Montes, L.M.; Pérez Campaña, R. Ecoestructura y Multifuncionalidad del Paisaje Agrourbano. Ediciones Universidad de Valladolid 2009, 12, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Campaña, R.; Valenzuela-Montes, L.M. Nodes of a peri-urban agricultural landscape at local level: An interpretation of their contribution to the eco-structure. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 406–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitay, H.; Finlayson, C.M.; Davidson, N. A Framework for Assessing the Vulnerability of Wetlands to Climate Change; Ramsar Convention Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Campaña, R. La vega del Guadalfeo Como Paisaje Agrario Periurbano. Transformación, Ecoestructura y Multifuncionalidad; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2013; Available online: http://purl.org/dc/dcmitype/Text (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- Flora, C.B. Rural Communities: Legacy and Change; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-8133-4971-8. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Karvonen, A.; Raven, R. The Experimental City; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-317-51715-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wardekker, J.A.; de Jong, A.; Knoop, J.M.; van der Sluijs, J.P. Operationalising a resilience approach to adapting an urban delta to uncertain climate changes. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gunderson, L.H.; Carpenter, S.R.; Folke, C.; Olsson, P.; Peterson, G. Water RATs (Resilience, Adaptability, and Transformability) in Lake and Wetland Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, art16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.; Schmidt, S. Designing Wetlands as an Essential Infrastructural Element for Urban Development in the era of Climate Change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bai, X.; Roberts, B.; Chen, J. Urban sustainability experiments in Asia: Patterns and pathways. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Lara, J.A.; Zúñiga-Antón, M.; Pérez-Campaña, R. European spatial planning observatories and maps: Merely spatial databases or also effective tools for planning? Environ. Plann B Plann Des. 2015, 42, 904–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-Basu, A.; Bharat, G.K.; Chakraborty, P.; Sarkar, S.K. Adaptive co-management model for the East Kolkata wetlands: A sustainable solution to manage the rapid ecological transformation of a peri-urban landscape. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWT Consulting. Good Practices Handbook for Integrating Urban Development and Wetland Conservation; Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust: Slimbridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Community Capitals | Contribution of the Charca |

|---|---|

| Natural | The project has entailed the recovering of a wetland area that constitutes one of the most important ecological nodes at local, sub-regional and even regional level. Furthermore, the area is protected as Nature Concerted Reserve. It also constitutes an “environmental facility” according to the interpretation of the Spanish Constitution. |

| Cultural | The project represents the cultural expression of the community regarding its local landscape; the Charca constitutes one of the last redoubts of sugar cane in Europe. |

| Political | The project has allowed the community to fully participate in the area protection, design and management. |

| Social | Networking is a principal component of the Charca experience, not just through the formal network that the Follow-up Commission entails, but also through the extended network, including other organizations, institutions and individuals. |

| Financial or economic | The area was acquired by the Local Council, making the Charca a municipal property. Besides, being protected as Nature Concerted Reserve, the Charca may participate in funding calls for promoting conservation and public use of Protected Areas. |

| Physical or built capital | The Charca is considered as an environmental facility and as a green-blue infrastructure. Bird hides and a nature classroom have been built in the Charca. |

| Human capital | The close implication of primary and secondary schools through environmental educational activities is contributing to increasing collective knowledge and awareness about different topics related to the planning and management of the Charca. Some students are later becoming volunteers for managing the area. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salizzoni, E.; Pérez-Campaña, R.; Alcalde-Rodríguez, F.; Talavera-Garcia, R. Local Planning Practice towards Resilience: Insights from the Adaptive Co-Management and Design of a Mediterranean Wetland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072900

Salizzoni E, Pérez-Campaña R, Alcalde-Rodríguez F, Talavera-Garcia R. Local Planning Practice towards Resilience: Insights from the Adaptive Co-Management and Design of a Mediterranean Wetland. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072900

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalizzoni, Emma, Rocío Pérez-Campaña, Fernando Alcalde-Rodríguez, and Ruben Talavera-Garcia. 2020. "Local Planning Practice towards Resilience: Insights from the Adaptive Co-Management and Design of a Mediterranean Wetland" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072900

APA StyleSalizzoni, E., Pérez-Campaña, R., Alcalde-Rodríguez, F., & Talavera-Garcia, R. (2020). Local Planning Practice towards Resilience: Insights from the Adaptive Co-Management and Design of a Mediterranean Wetland. Sustainability, 12(7), 2900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072900