Productivity Evaluation of Tourism and Culture for Sustainable Economic Development: Analyzing South Korea’s Metropolitan Regions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Economic Impact of Tourism

2.2. Contextual Setting: Overview of Tourism in South Korea

2.3. Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) and Malmquist Productivity Index (MPI)

2.4. DEA and MPI in Tourism and Hospitality

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Selection: Decision Making Unit (DMU), Input, and Output

3.2. Analysis Metrics

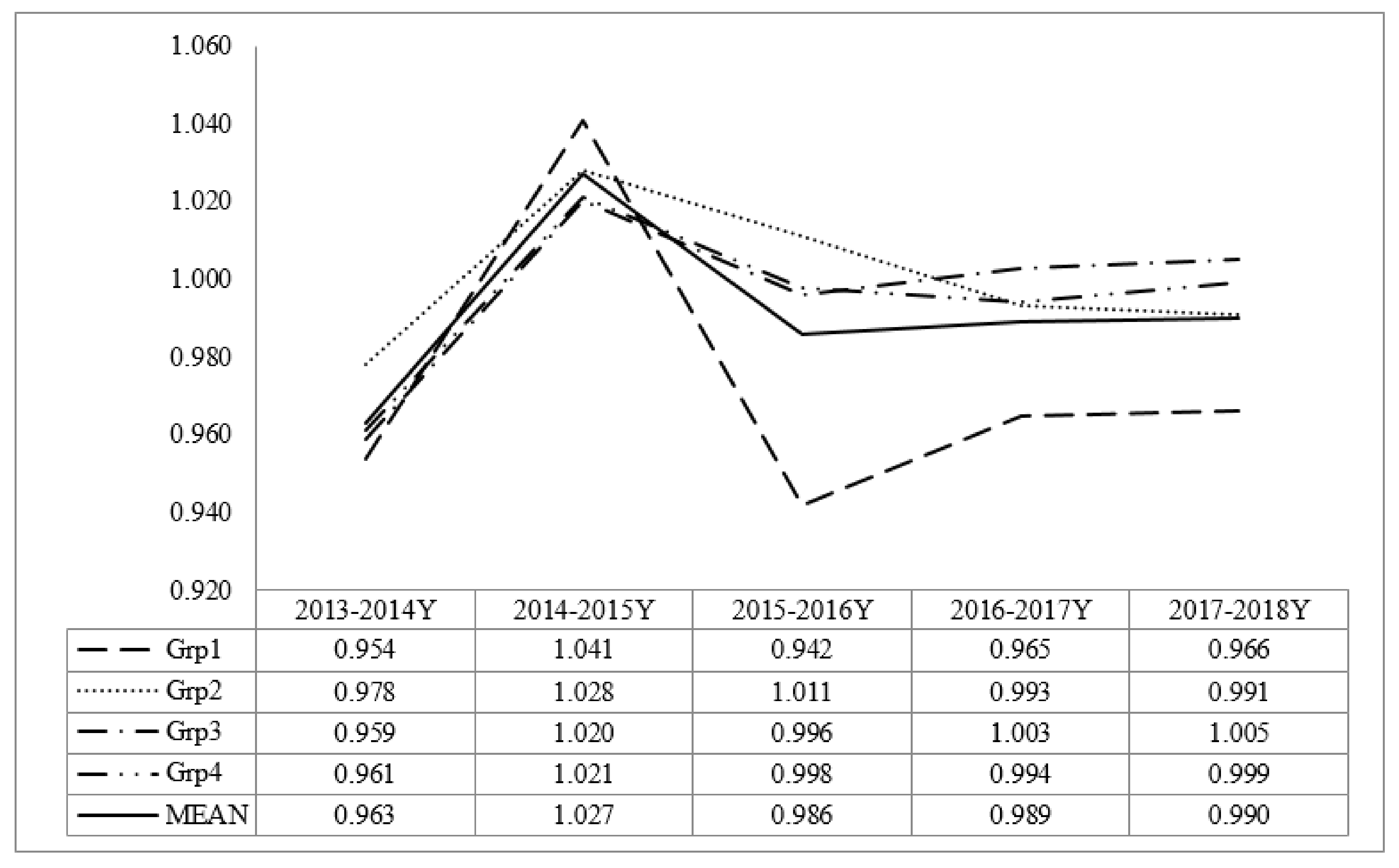

4. Results

4.1. Gross Value Added

4.2. Employment

4.3. Comparison of Averaged MPI Values between Industries

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sönmez, S. Working producers, leisured consumers: Women as producers and consumers of tourism in developing regions. In Women as Producers and Consumers of Tourism in Developing Regions; Apostolopoulos, Y., Sönmez, S., Timothy, D.J., Eds.; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 2001; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- WTTC Travel & Tourism Continues Strong Growth above Global GDP. Available online: https://www.wttc.org/about/media-centre/press-releases/press-releases/2019/travel-tourism-continues-strong-growth-above-global-gdp/ (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- World Tourism Organization UNWTO Tourism Highlights. Available online: www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284419876 (accessed on 11 July 2019).

- Sánchez del Río-Vázquez, M.-E.; Rodríguez-Rad, C.J.; Revilla-Camacho, M.-Á. Relevance of social, economic, and environmental impacts on residents’ satisfaction with the public administration of tourism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akadiri, S.; Akadiri, A.; Alola, U.V. Is there growth impact of tourism? Evidence from selected small island states. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1480–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, B.; Fletcher, J. The economic impact of tourism in the Seychelles. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Hall, C.M. Contemporary Tourism: An International Approach, 3rd ed.; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 1911396773. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Tourism for Sustainable Development in Least Developed Countries: Leveraging Resources for Sustainable Tourism with the Enhanced Integrated Framework; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP and UNWTO Making Tourism More Sustainable-A Guide for Policy Makers. Available online: https://sdt.unwto.org/content/about-us-5 (accessed on 14 July 2019).

- Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y. Total factor productivity assessment of tourism industry: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlight; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Why Tourism? Available online: https://www.unwto.org/why-tourism (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurowski, C.; Daniels, M.J.; Pennington-Gray, L. The distribution of tourism benefits. In Quality Tourism Experiences; Jennings, G., Nickerson, N.P., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2006; pp. 192–207. [Google Scholar]

- Murzyn-Kupisz, M.; Działek, J. Cultural heritage in building and enhancing social capital. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 3, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, R.; Jolliffe, L. Cultural rural tourism: Evidence from Canada. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.F.; Duinker, P.; Sheehan, L.; Chute, J. Sustainable Mi’kmaw cultural tourism development in Nova Scotia, Canada: Examining cultural tourist and Mi’kmaw perspectives. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, J.S. Pattern and impact of tourism on the environment of the Caribbean. Tour. Manag. 1988, 9, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigós-Simón, F.J.; Galdón-Salvador, J.L.; Gil-Pechuán, I. The economic sustainability of tourism growth through leakage calculation. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 721–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, G.F. Resident perceptions of the impact of tourism on an Australian city. J. Travel Res. 1992, 30, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belisle, F.J.; Hoy, D.R. The perceived impact of tourism by residents a case study in Santa Marta, Colombia. Ann. Tour. Res. 1980, 7, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wall, G. Authenticity in ethnic tourism: Domestic tourists’ perspectives. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Beyond authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Korea. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2018; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Information System Tourism Statistics. Available online: https://www.tour.go.kr (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Park, K.-J. President Moon attended the National Tourism Strategy. “Tourism surplus is possible if we make it attractive”. Yunhap 2019. [Translated]. Available online: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20190402098851001 (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Kim, H.; Choe, Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.J. For sustainable benefits and legacies of mega-events: A case study of the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics from the perspective of the volunteer co-creators. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism. 2020 Budget Plan for Tourism Policy and Industry. Available online: https://www.mcst.go.kr/ (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bojanic, D.C.; Lo, M. A comparison of the moderating effect of tourism reliance on the economic development for islands and other countries. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoti, S.; McAleer, M.; Shareef, R. Modelling international tourism and country risk spillovers for Cyprus and Malta. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1472–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckelmann, A. Domestic tourism—A chance for regional development in Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.M.; Chen, L.H. Productivity growth of taiwanese international tourist hotels in a metafrontier framework. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 57, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.P. Evaluating the efficiency of a small hotel chain with a Malmquist productivity index. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2005, 7, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.J. The measurement of productive efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1957, 120, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, Y. Malmquist productivity index for multi time periods. Int. J. Data Envel. Anal. 2014, 2, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Lu, L.T.; Sung, A.D. A measure to the operational performance of international hotels in Taiwan: DEA and Malmquist approach. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2012, 2, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Caves, D.W.; Christense, L.R.; Diewert, W.E. Multilateral comparisons of output, input, and productivity using superlative index numbers. Econ. J. 1982, 92, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, D.W.; Christense, L.R.; Diewert, W.E. The economic theory of index numbers and the measurement of input, output, and productivity. Econometrica 1982, 50, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S.; Lindgren, B.; Roos, P. Productivity developments in Swedish hospitals: A Malmquist output index approach. In Data Envelopment Analysis: Theory, Methodology, and Applications; Charnes, A., Cooper, W.W., Lewin, A.Y., Seiford, L.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. A non-radial Malmquist productivity index with an illustrative application to Chinese major industries. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2003, 83, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camanho, A.S.; Dyson, R.G. Data envelopment analysis and Malmquist indices for measuring group performance. J. Prod. Anal. 2006, 26, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grifell-Tatjé, E.; Grosskopf, S.; Lovell, C.A.K. Biased technical change and the Malmquist productivity index. Scand. J. Econ. 1997, 99, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peypoch, N.; Solonandrasana, B. Aggregate efficiency and productivity. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.I.; Fish, M.; Xia, Y.; Michello, F. Measuring efficiency in the hotel industry: A stochastic frontier approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1999, 18, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peypoch, N. On measuring tourism productivity. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 12, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.G.; Cvelbar, L.K.; Pahor, M. Performance drivers in the casino industry: Evidence from Slovenia. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.G.; Dwyer, L. Benchmarking international tourism destinations. Tour. Econ. 2013, 19, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barros, C.P. Measuring efficiency in the hotel sector. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, R.; Dittman, D.A. Evaluating a hotel GM’s performance. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1995, 36, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.A.; Morey, R.C. Increasing the efficiency of corporate travel management through macro benchmarking. J. Travel Res. 1995, 33, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, N.; Howcroft, B.; Drake, L. The use of data envelopment analysis to monitor hotel productivity. Prog. Tour. Hosp. Res. 1997, 3, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.I.; Fok, R.; Scott, J. Hotel industry efficiency: An adavanced linear programming examination. Am. Bus. Rev. 2000, 18, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.R.; Ragsdale, C.T. The competitive market efficiency of hotel brands: An application of data envelopment analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2002, 26, 332–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, D.; Thompson, G.M. Multiunit restaurant productivity assessment using three-phase data envelopment analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reynolds, D.; Biel, D. Incorporating satisfaction measures into a restaurant productivity index. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, D. Hospitality-productivity assessment. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2003, 2, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.G.; Barros, C. Performance analysis of the gulf hotel industry: A Malmquist index with bias correction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.P.; Alves, F.P. Productivity in the tourism industry. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2004, 10, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Liang, M. Evolutional model of tourism efficiency based on the DEA method: A case study of cities in Guangdong Province, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.A.P.; Santos, C.A. The measurement of efficiency in Portuguese Hotels using data envelopment analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.P.; Dieke, P.U.C. Analyzing the total productivity change in travel agencies. Tour. Anal. 2007, 12, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Z. Managing efficiency in international tourist hotels in Taipei using a DEA model with non-discretionary inputs. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tsai, H.; Zhou, Z. Improving efficiency in international tourist hotels in Taipei using a non-radial DEA model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 23, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosetti, V.; Cassinelli, M.; Lanza, A. Becnchmarking in Tourism Destination, Keeping in Mind the Sustainable Paradigm; Nota di Lavoro; Springer: Milano, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cracolici, M.F.; Nijkamp, P.; Cuffaro, M. Efficiency and productivity of Italian tourist destinations: A quantitative estimation based on data envelopment analysis and the malmquist method. In Advances in Modern Tourism Research; Matias, A., Nijkamp, P., Neto, P., Eds.; Physica-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 325–343. [Google Scholar]

- Cuccia, T.; Guccio, C.; Rizzo, I. UNESCO sites and performance trend of Italian regional tourism destinations: A two-stage DEA window analysis with spatial interaction. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 316–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafurida, F.; Pratiwi, E.N. Financial independence of regencies and cities in central java. Econ. J. Emerg. Mark. 2017, 9, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Statistics Korea Korean Statistical Information Service. Available online: http://kosis.kr/index/index.do (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety Local Finance Integrated Open System. Available online: http://lofin.mois.go.kr/portal/main.do (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Wood, R.E. Caribbean cruise tourism: Globalization at sea. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, J.-A.; Weeden, C. Stakeholders, the natural environment and the future of Caribbean cruise tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Global Report on City Tourism; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Premack, R. A Row With China Over U.S. Missiles Is Devastating South Korea’s Tourism Industry. Time. Available online: https://time.com/4734066/south-korea-tourism-china-thaad/ (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Carbone, M. Sustainable tourism in developing countries: Poverty alleviation, participatory planning, and ethical issues. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2005, 17, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

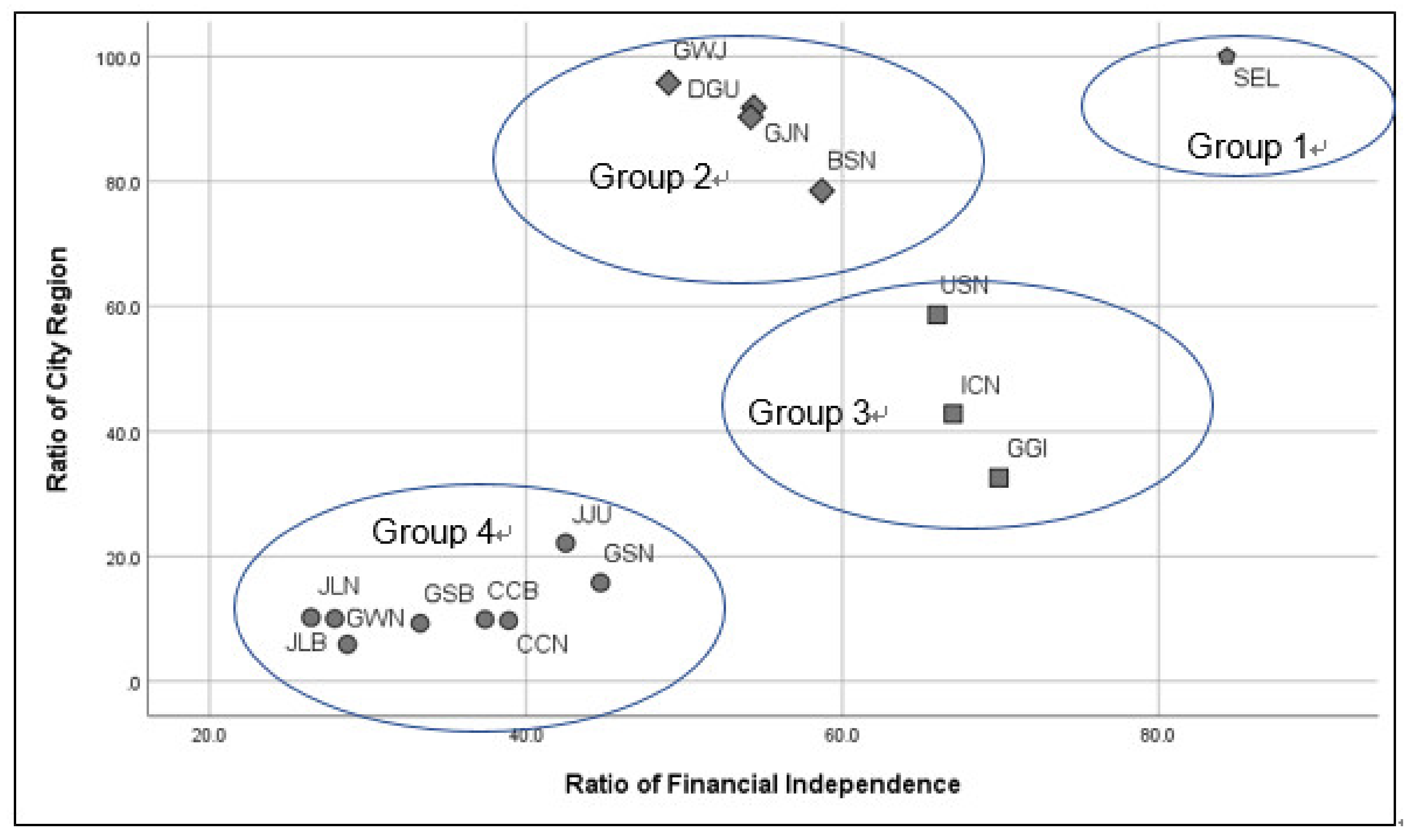

| Region | Label | Financial Independence | Rate of City Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seoul Metropolitan City | SEL | 84.3 | 100.0 |

| Busan Metropolitan City | BSN | 58.7 | 78.5 |

| Daegu Metropolitan City | DGU | 54.2 | 90.3 |

| Incheon Metropolitan City | ICN | 67.0 | 42.8 |

| Gwangju Metropolitan City | GWJ | 49.0 | 95.8 |

| Daejeon metropolitan City | GJN | 54.4 | 91.8 |

| Ulsan Metropolitan City | USN | 66.0 | 58.7 |

| Gyeonggi-do | GGI | 69.9 | 32.5 |

| Gangwon-do | GWN | 28.7 | 5.9 |

| Chungcheongbuk-do | CCB | 37.4 | 9.9 |

| Chungcheongnam-do | CCN | 38.9 | 9.7 |

| Jeollabuk-do | JLB | 27.9 | 10.0 |

| Jeollanam-do | JLN | 26.4 | 10.2 |

| Gyeongsangbuk-do | GSB | 33.3 | 9.3 |

| Gyeongsangnam-do | GSN | 44.7 | 15.8 |

| Jeju-do | JJU | 42.5 | 22.1 |

| Variables | Unit | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Budget (TB) | 1 billion won (public input) | 32,259.08 | 125,675.00 | 63,243.81 | 31,617.83 |

| Culture and Tourism Budget (CTB) | 789.76 | 8122.94 | 3073.99 | 2478.66 | |

| Other Budget (OB = TB − CTB) | 31,078.89 | 117,819.89 | 60,169.81 | 29,173.71 | |

| Total Business Establishments (TBE) | Number of establishments (Private input) | 682,183 | 1,330,044 | 973,332 | 228,483 |

| Art, Sports and Leisure related Services Sector (ASLS) | 18,295 | 37,245 | 27,279 | 7027 | |

| Accommodation and Food Sector (AFS) | 119,108 | 289,615 | 180,013 | 62,919 | |

| Other Business Establishments (OBE) | 543,624 | 1,003,216 | 766,041 | 162,038 | |

| Number of Hotel Rooms (NHR) | 12,945 | 95,966 | 41,632 | 27,943 | |

| Gross Value Added (GVA) | Value added 1 billion won (output) | 181,349.91 | 551,926.28 | 384,967.47 | 132,476.20 |

| Culture and Services Value Added (CSVA) | 6913.02 | 14,702.90 | 11,795.44 | 2967.42 | |

| Accommodation and Food Services VA (AFSVA) | 5744.05 | 11,566.53 | 9347.29 | 2141.20 | |

| Other VA (OVA) | 168,302.17 | 526,441.94 | 363,824.75 | 127,691.38 | |

| Total Employment (TE) | Person (private input/public output) | 3,286,493 | 6,755,369 | 5,218,287 | 1,179,632 |

| Art, Sports and Leisure related Services Employment (ASLSE) | 55,665 | 136,347 | 96,512 | 28,055 | |

| Accommodation and Food Services Employment (AFSE) | 351,423 | 733,520 | 534,293 | 130,761 | |

| Other Employment (OE) | 2,879,405 | 5,983,264 | 4,587,482 | 1,031,316 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joun, H.-J.; Kim, H. Productivity Evaluation of Tourism and Culture for Sustainable Economic Development: Analyzing South Korea’s Metropolitan Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2912. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072912

Joun H-J, Kim H. Productivity Evaluation of Tourism and Culture for Sustainable Economic Development: Analyzing South Korea’s Metropolitan Regions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2912. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072912

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoun, Hyo-Jae, and Hany Kim. 2020. "Productivity Evaluation of Tourism and Culture for Sustainable Economic Development: Analyzing South Korea’s Metropolitan Regions" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2912. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072912