1. Introduction

Cycling is widely acknowledged as a sustainable and clean mode of travel with significant advantages in short-distance travel [

1]. It is commonly considered a healthy lifestyle to reduce deaths caused by the urban sedentary lifestyle and an effective way to alleviate air pollution caused by automobile exhaust [

2,

3,

4]. During the 1980s, China was called the “kingdom of bicycles”, and bicycles were the most common urban transportation. However, with the rapid development of motorization and urbanization, the proportion of cycling in Beijing had declined from 62.7% in 1986 to 12.4% in 2015 (see

Figure 1) [

5], due to a variety of factors. The increasing travel distance with the fast growth at the urban scale is partly responsible for the decrease of bicycle usage. Fifty-five percent of journeys in Beijing are still within five kilometers according to a 2014 survey, thanks to its reasonable urban layout and extensive living facilities. However, twelve percent of these short-distance trips were still made by car, which were fundamentally suitable for cycling [

6]. Therefore, it is very important to promote the prevalence of bicycles, particularly for short-distance travel, for the sake of the sustainable development of urban traffic.

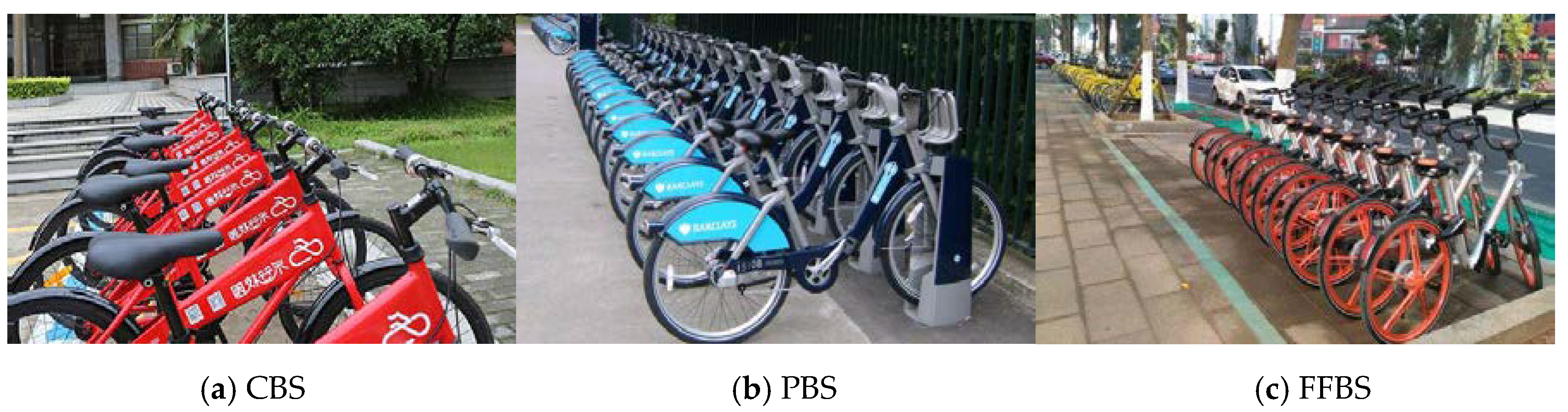

According to the success of Copenhagen and other cities, many measures have been taken in Beijing to improve the cycling environment. From 2013 to 2016, more than 700 kilometers of bike lanes were constructed in Beijing; 328,000 square meters of colored intersections were paved; 1702 meters of bike lanes were broadened. However, the popularity of the usage of bicycles as a transportation form is yet dissatisfactory. To promote sustainable transportation, the bike-sharing system has been valued. There are mainly three types of bike-sharing programs, including the public bike-sharing system (PBS), the closed campus bike-sharing system (CBS), and free-floating (FFBS). CBS (

Figure 2a) is a kind of bike-sharing system that is used only inside the campus. PBS (

Figure 2b) is often run or subsidized by the government, involving massive docking station constructions, whilst FFBS is a newer form, which has been developing rapidly in China since 2016. It is found that FFBS (

Figure 2c) not only provides a new kind of sharing mode, but also gives rise to an unexpected change for sustainable transport [

7].

FFBS, which is represented by OFO and MOBIKE, has emerged in China at the right moment as a result of the mobile Internet. FFBS are completely sponsored and operated by enterprises. They have overcome the limit of fixed sites, that is people can rent or return bikes anywhere. Each bike can be located by a Global Positioning System (GPS) module in its smart lock. Users can rent bikes by scanning a QR code (a kind of two-dimensional code) with the help of a smartphone. [

7] By June 2018, over 1.9 million bikes were available, and the average amount of daily usage reached approximately 2,250,000. The declining trend of the share rate of cycling for the past few years has been altered, or even slightly increased by 1.1%, with the emergence of FFBS [

5]. Such progress is beyond the other approaches. Therefore, it is of great importance to understand the motivations and barriers underlying the usage of shared bikes, so that further methods can be proposed to enhance the sustainability of FFBS and, more importantly, to promote the development of cycling.

2. Literature Review

In order to understand the cycling prevalence of FFBS, numerous studies have been conducted. The present research is mainly concerned with the impact of various factors such as social demography, travel details, infrastructure, meteorological environment, and FFBS operating system. Factors influencing the use of bicycles and PBS, which constitute a part of the basis for the current research, were also included in the literature review.

FFBS usage is related to social demographic factors. Most studies demonstrated that male cyclists outnumber female cyclists. Pucher et al. [

8] believed that there was a negative correlation between cycling frequency and age. The results of Guo showed that the usage of FFBS was affected by household bicycle/car ownership [

9]. It is generally believed that PBS users have high average incomes [

10], high levels of education [

11], and full-time or part-time employment [

12]. In addition to social demographic factors, travel details also affect FFBS usage: travel distance has a greater influence than travel time and purpose [

9,

13,

14]. Likewise, there is a relationship between infrastructure and FFBS usage. According to the study of Gamez-Perez [

15], a safe and adequate infrastructure is a guarantee for the potential usage of FFBS. Barnes [

16] found that setting up a dedicated bike road could increase the amount of cyclists by 1% to 2%. Stinson and Bhat [

17] made a survey and found that cyclists preferred continuous roads in cycling. Environmental factors are often a barrier to the use of FFBS. The study results of Li [

18] showed that reduced air pollution exhibited a favorable influence on non-motorized transport usage. It was also found that rainy weather discouraged the use of public bikes [

19]. Demand for FFBS is evidently reduced by temperature and poor air quality [

20]. Additionally, the exclusive advantages of FFBS are particularly important for its popularity. First of all, convenience is the major motivator for FFBS use [

21]. Other merits such as favorable ease of access with a smart phone, convenience of pickup and parking, low expense [

22], and extensive presence of docking stations within 250 m of their workplace were found to be statistically significant contributions to the preference for shared bikes [

10], while primary obstacles for FFBS usage came from malfunction and limited regulations [

23]. Additionally, FFBS is confronted with competition from the others transportation in terms of cost and travel experience [

24].

However, the interrelationship between these factors is complex, and the governing mechanism is unclear. Scholars try to explore the unobservable potential variables based on the perspective of social psychology. Some new aspects of social psychology have been explored with the widespread application of planned behavior theory (TPB) [

25], among which attitude, social norms, and perceived behavior control are the three most important potential variables.

In the early stage, the cycling behavior was studied based on TPB, and some general laws were found. Dill [

26] argued that a positive attitude toward cycling led to the increase of the likelihood of cycling. Similarly, Abraham et al. [

27] argued that negative views of driving also encouraged people to use bicycles. The studies of De [

28] showed that cyclists were more likely to get help and support from cycling groups. At the same time, Bamber [

24] found that people who had ridden a bicycle had less anxieties about and more willingness toward cycling. TPB can be also used to explain the intentions and behaviors towards FFBS. Scholars studied the social effects of shared bikes: the membership increase of shared bikes seemed to be slightly due to contagion from neighboring membership [

29]. Social influence has a positive effect on users’ trust attitude and hence subjective well-being [

30]. According to a structural equation model (SEM) of intentions, the significance of factors is a sequence of subjective norms > attitude > perceived pleasure > effects of flexibility and convenience [

31].

Compared with bicycles, except for some common socio-demographic factors, the use of PBS and FFBS is more susceptible to the system factors and perceived potential variables, while the infrastructure displays an insignificant influence. More details are shown in

Table 1.

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

The following variables are involved according to the theoretical framework of standard TPB: ATT (attitude), SN (subjective norm), PBC (perceived behavior control), BI (intention), and BV (behavior) [

25]. Attitude indicates negative or positive assessment of persons towards some behavior; a subjective norm refers to the detailed feelings of other people regarding decision making; and PBC is similar to the concept of self-control over one’s own behavior. On the basis of TPB, behavior is mainly predicted by intentions, which inversely suffer from the influences of ATT towards the behavior, PBC over the behavior, and SN pertaining to the behavior.

TPB is a kind of primary social-cognitive theory developed by Ajzen [

25], who implied that personal behavior is mainly predicted by behavioral intentions, which are further determined by three salient motivational factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (PBC). Despite that the basic model could provide an interpretation for a majority of the alterations in intention, several scholars have proposed that it would lead to an evident improvement in its explanatory power with consideration of attitudes toward bad weather, attitudes toward cars [

32], and external restrictions (infrastructure). On the basis of TPB, Han et al. [

33] predicted the intention of bike traveling, using the attractiveness of unsustainable alternatives as a moderator and personal norm and past behavior as predictors. The results offered a thorough understanding of the role of volitional and non-volitional processes, personal norm, past behavior, and the attractiveness of unsustainable alternatives in explaining the intention formation of bike traveling. The predicted intention of car usage [

24] indicated that role beliefs increased the explanatory power of the Ajzen model, and car use habit significantly contributed to the predictive power of the Ajzen model, while the personal norm exerted an insignificant effect either on intention or on behavior.

However, the explanatory power of these variables was involved in a few related explorations for FFBS usage. As a consequence, the present study employed an extended the TPB model that accounted for the basic TPB model, as well as attitudes toward bad weather, attitudes toward cars, and external restrictions regarding infrastructure, to explain FFBS usage intentions and behaviors.

2.1.1. Original PBC Variables

Perceived behavior control (PBC): Perceived behavior control means self-control over one’s own FFBS usage behavior.

Subjective norm (SN): Subjective norms mean the social pressure received from several important referents to perform a particular behavior.

Attitude towards FFBS (BATT): Attitude towards FFBS is the original attitude, explained as the extent of one’s favor or praise towards FFBS usage behavior (BATT is used to represent attitude towards FFBS here to distinguish it from other attitudes).

2.1.2. Additional Variables

Attitude towards cars (CATT): Attitude towards cars represents the inclination toward FFBS usage on the condition of the preference for cars.

Attitude towards bad weather (WATT): Attitudes towards bad weather, exhaust fumes, and haze represent the inclination towards FFBS usage in the case of bad weather.

External restrictions regarding infrastructure (IER): External restrictions regarding infrastructure reflect restrictions for FFBS use that are beyond the control of the user.

In order to explain the prevalence in the choice of FFBS as a mode of transport, three main concerns are involved in the present paper, including: (1) identification of the psychosocial factors that play a role in FFBS use intention and actual behaviors; (2) the complex interrelation among those factors; (3) advice for promoting FFBS use. It should be noted that this paper mainly discusses the influence of cars on the use of FFBS, considering that travelling by bus belongs to a green mode of transportation.

4. Methods

4.1. Participants and Procedure

In this study, data were collected within five days in July 2018 from an online survey in Beijing. The questionnaire link was forwarded to 12 WeChat groups covering people with differences in age, education, and cycling experience. To ensure that all the respondents were residents living in Beijing, the questionnaire link was set with IP restrictions accessible only for respondents in Beijing. Three-hundred-eighty-five group members responded, and each were paid CNY 4 (approximately $0.44). After the filtration of incomplete data and extreme data (i.e., those respondents whose answering time was 6 min less than the minimum time limit), there were in all 352 valid questionnaires from 197 women and 155 men, with an acceptable proportion of 91.43%.

4.2. Measure

The questionnaire included 3 parts: introduction, demographic information, and latent variable items. The introduction part helped participants complete the questionnaire; the demographic information part mainly included gender, age, income, education, occupation, vehicle ownership, cycling ability, frequency of FFBS use, and working location; and the latent variable items were derived from the hypothetical framework of this paper and previous studies. According to the actual usage of shared bikes, a six-point scale was designed to measure the variable BV, and the other variables were evaluated according to a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = “strongly unlikely” to 5 = “strong likely”. A further revision was employed for the questionnaire to enhance its clarity and reliability based on feedback, after a pretest of 100 people.

- ▪

Perceived behavior control (PBC):

Three items were used to assess perceived behavior control.

Respondents demonstrated the following three behavioral beliefs for FFBS:

PBC 1: I have the ability to pay the deposit;

PBC 2: I can afford a membership card;

PBC 3: I can afford to use it;

- ▪

Subjective norm (SN):

Five items were used to assess subjective norm.

SN1: My friends would support me to use shared bikes;

SN2: My family would support me to use shared bikes;

SN3: Most people in society would support me to use shared bikes;

SN4: News medium would support me to use shared bikes;

SN5: Social media would support me to use shared bikes;

- ▪

Attitude towards FFBS (BATT):

Five items were used to assess residents’ attitude towards FFBS.

BATT1: It is economical because I don’t have to buy a bicycle;

BATT2: It is economical because it’s cheap to use;

BATT3: It is convenient because it can be rented anywhere;

BATT4: It is convenient because I can stop to do other things at any time in travel;

BATT5: It is convenient for I need not to worry about maintenance and theft;

- ▪

Attitude towards cars (CATT):

Five items were used to assess residents’ attitude towards cars.

CATT1: It is economical;

CATT2: It is convenient;

CATT3: It is efficient;

CATT4: It is comfortable;

CATT5: It is safe;

- ▪

Attitude towards bad weather (WATT):

Two items were used to assess residents’ attitude towards bad weather.

WATT1: It is uncomfortable as it exposes me to exhaust fumes and haze directly;

WATT2: It is uncomfortable because I might suffer from bad weather;

- ▪

External restrictions regarding infrastructure (IER):

Three items were used to assess residents’ attitude towards bad weather.

IER 1: Incomplete bike lanes would limit my use of FFBS;

IER 2: Insufficient parking space would limit my use of FFBS;

IER 3: Poor cycling environment (shade) would limit my use of FFBS;

- ▪

FFBS usage intentions (BI):

Three items were used to measure residents’ FFBS usage intentions.

IN1: I intend to travel by shared bikes frequently in the next three months;

IN2: I try to travel by shared bikes frequently in the next three months;

IN3: I plan to travel by shared bikes frequently in the next three months;

- ▪

FFBS usage behavior (BV):

The FFBS usage behavior was measured by one item:

BV1: How often have you used BSS in the past three months? (1 never 2 once a month 3 once a week 4 2–4 times a week 5 almost every weekday 6 almost every day)

6. Discussion

The current study was primarily aimed at identifying the psychosocial variables that play a role in FFBS use intention and actual behaviors, as well as to further explore the complex interrelation among those factors and to provide a useful effective method to promote FFBS use.

As expected, the extended planned behavior theory in this paper could reasonably explain FFBS usage intention and behavior. The structure involved herein showed that the positive indicators associated with FFBS usage could be revealed through three latent variables: perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and residents’ attitudes toward FFBS, among which residents’ attitudes toward FFBS were related to indicators that made cycling a competitive mode of transport. On the other hand, the negative indicators associated with FFBS usage could be revealed through three latent variables: attitudes toward cars, attitudes toward bad weather, and external constraints regarding infrastructure, among which bad weather was the biggest obstacle for residents to use FFBS.

6.1. Influence of Demographic Variables

The current study investigated the correlation between extended TPB variables and demographic factors. According to the results of independent

t-tests, residents’ gender, age, car ownership, FFBS riding experience, and riding ability had significant influences on the psychological variables. In the current study, men showed a better attitude toward cars; one reasonable explanation might be that cars exhibit more attraction for men than for women and that women account for a relatively small proportion of licensed drivers. [

39]. This implied that motivation for car usage was quite different for men and women. Thus, men could be affected by factors that might make little sense for women. People under 60 years old were more willing to use FFBS, which might be due to the higher ability of young people to accept new things, and studies showed that people who were more receptive to new things were more likely to perceive the ease of use and usefulness of shared bikes [

40]. There was a dissimilarity in attitudes towards cars between people with cars and those without. This was related to car owners being used to driving for travel, and thus, they were less susceptible to new ways of travel. In the current study, there was a clear difference between the perceptions of users that had FFBS experience and those that never used a shared bike [

41], which was consistent with previous studies. Adequate advice for the promotion in FFBS is to encourage people to experience FFBS riding [

42]. In addition, it was reasonable that FFBS was more attractive for skilled cyclists with stronger subjective norms. On the other hand, according to the results of the analysis of variance, the significant influence of different demographic variables on the frequency of shared bikes was identified through this study. Men, younger people, and students were more likely to use shared bikes. Car owners and skilled cyclists showed higher enthusiasm toward shared cycling. Well-educated cyclists also showed higher inclination to becoming bike-sharing users.

6.2. Influence of Psychosocial Variables

6.2.1. Perceptual Behavior Control

The perceptual behavior control explained by resources and ability (deposit, membership card, cost) had a direct and predictive effect on FFBS use behavior: the stronger the perceived behavioral control, the more likely residents were to use FFBS, consistent with previous work [

43]. Therefore, it is adequate advice to lower the cost for FFBS usage.

6.2.2. Subjective Norms

A general consensus has been achieved by most researches that subjective norms have predictive effects on intention [

44], also confirmed in this study. In addition, the results from the current study revealed the crucial role that social media, news media, and society play in FFBS prevalence. With the development of society, people are more and more dependent on social media and news media for information. Moreover, shared bikes have obvious social attributes, which leads to the significant influence of media on residents’ behaviors. Policies could encourage the recommendation of this environmentally-friendly travel mode to neighboring friends, relatives, and social contacts [

7,

45]. On the other hand, urban governments should dispel residents’ anxieties through news media, social atmosphere, and word-of-mouth among groups [

3] to improve residents’ willingness to use shared bikes.

6.2.3. Attitudes toward FFBS

The results of this paper showed that a positive attitude towards shared bikes was the key to promote residents to use shared bikes. One possible explanation might be the unique advantages of FFBS that it can be rented and returned anywhere and anytime with a low cost and that in some cases, it could replace one’s own bicycle, as well as the users are relieved from the maintenance work and security anxieties. These are beyond the capability of other vehicles. This result was in accordance with the finding of Yan [

31]: the more these characteristics are perceived by the cyclist with use, the more important convenience becomes to explain their decisions. This paper also explored the success of FFBS over the PBS launched by the Beijing government. Although there are seemingly plenty of PBS stations in Beijing, people often have to walk more than 200 m to a fixed site to rent a bike, and they are not sure about the location or the existence of a PBS station near the destination. In addition, the procedure to register membership and get a card is time consuming, and thus, it is impractical for non-members to use a bike right away. However, all these inconveniences are eliminated with FFBS: people can even get an available shared bike at the gate of the community by scanning a QR code with a smartphone and leave the bike anywhere at the destination. Therefore, the convenience of user experience belongs to an important user experience that FFBS operators should further improve, and some potential approaches for the improvement of the service level should also be considered.

6.2.4. Attitudes toward Cars

The current study confirmed the competitive relationship between cars and FFBS. The more friendly residents are toward cars, the less likely they are to choose shared bikes. Koller found that car usage is often accompanied by functional, economic, emotional, and social values [

32]. Interestingly, contrary to expectations, the results of this paper indicated that the “comfort and safety of cars” was the main reason for people to choose cars over “time saving”. Such a conclusion was established based on the transportation mode itself and the perception of users, without considering other potential factors such as the daily intention to ride a bike. Therefore, in an area suitable for bicycle travel (such as the transit-oriented development area), targeted measures and designs to limit cars, such as higher parking fees, less parking convenience, and building a dense road network in small blocks, can effectively improve residents’ intention to choose FFBS.

6.2.5. Attitudes toward Bad Weather

Previous studies had consistently reported the negative effects of bad weather, such as rainy weather [

19], temperature, and poor air quality [

18] as observation variables. In the present study, attitudes toward bad weather represented by variables of rainy weather, exhaust fumes, and haze were also a significant factor for intention, consistent with previous work. This may be due to the limitation of FFBS. Residents’ intention to travel by shared bikes will be greatly reduced under harsh travel environment such as rain, snow, exhaust fumes, and haze. Therefore, it is a key consideration for FFBS operators to address the restrictions of bicycles by corresponding optimization, such as the incorporation of fenders and adding rain shelters.

6.2.6. External Restrictions Regarding Infrastructure

Previous studies have emphasized the importance of infrastructure for bike or shared bike trips; however, this paper showed a different conclusion: limitations regarding infrastructure such as inadequate bike lanes had no significant effect on the change in the willingness to use FFBS. One possible explanation is that in terms of infrastructure in Beijing, which is far from satisfactory even with the improvement in recent years, the convenience brought by FFBS outweighs the obstacles of infrastructure. This conclusion explains why Beijing’s efforts in infrastructure are not as significant an effect on shared bike usage.