Sustainable Career Development of Newly Hired Executives—A Dynamic Process Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Newly Hired Executive from Outside a Company

2.2. Sustainable Career Development from a Dynamic Perspective

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

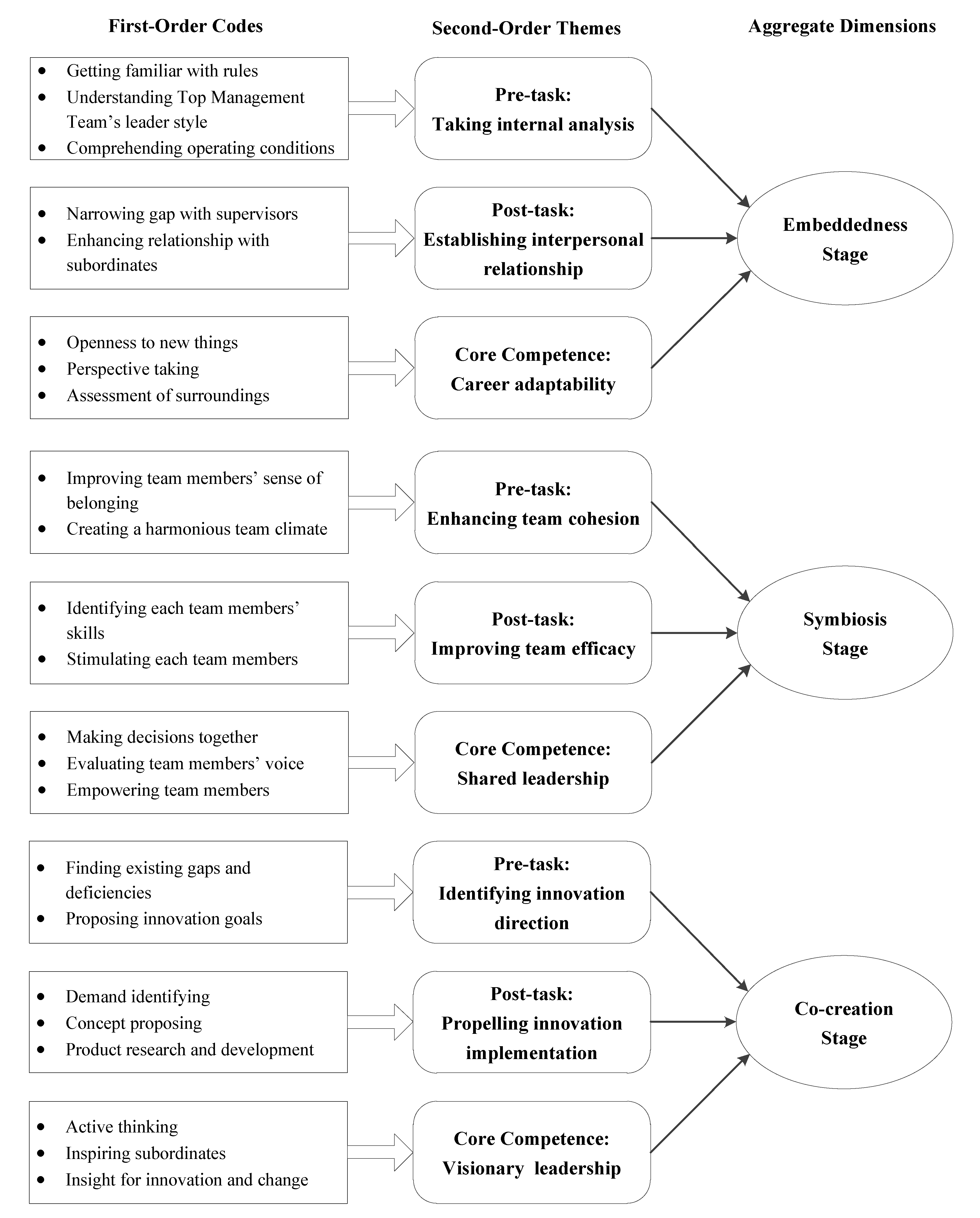

4. Findings

4.1. Embeddedness Stage

4.2. Symbiosis Stage

4.3. Cocreation Stage

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Limitations and Further Directions for Research

5.3. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geletkanycz, M.A. The salience of ‘culture’s consequences’: The effects of cultural values on top executive commitment to the status quo. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Erdogan, B.; Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J. A longitudinal study of the moderating role of extraversion: Leader-member exchange, performance, and turnover during new executive development. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Finkelstein, S.; Mooney, A.C. Executive job demands: New insights for explaining strategic decisions and leader behaviors. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, A.R. New Executives from Inside or Outside? The Effect of Executive Replacement on Organizational Change. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, C.M.; Certo, S.T.; Dalton, D.R. International experience in the executive suite: The path to prosperity? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaevli, A.; Zajac, E.J. When do outsider ceos generate strategic change? The enabling role of corporate stability. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 1267–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, I. Triggering absorptive capacity in organizations: Ceo succession as a knowledge enabler. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1844–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, B.; Elias, R.; De Clercy, C.; Rowe, G. Leadership succession in different types of organizations: What business and political successions may learn from each other. Leadersh. Q. 2020, 31, 101289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, M. Holes at the top. why CEO firings backfire. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.; Cannella, A.A. Power dynamics within top management and their impacts on ceo dismissal followed by inside succession. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, M.D. Help newly hired executives adapt quickly. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, W.E.; Huang, K.H.C.; Jones, G.H. Executive onboarding: Ensuring the success of the newly hired department chair. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, K.S. Confronting an inconvenient truth: Developing succession management capabilities for the inevitable loss of executive talent. Organ. Dyn. 2019, 48, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Fukutomi, G.D.S. The seasons of a CEO’s tenure. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 719–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambatista, R.C. Jumping through hoops: A longitudinal study of leader life cycles in the nba. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kesner, I.F.; Sebora, T.C. Executive succession: Past, present & future. J. Manag. 1994, 20, 327–372. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, B.L.; Ketchen, D.J.; Gangloff, K.A.; Shook, C.L. Investor perceptions of CEO successor selection in the wake of integrity and competence failures: A policy capturing study. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 2135–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaevli, A. Performance consequences of new CEO ‘outsiderness’: Moderating effects of pre- and post-succession contexts. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W. The dynamics of the CEO-board relationship: An evolutionary perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; De Vos, A. Sustainable careers: Introductory chapter. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Careers; De Vos, A., Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Heijden, B.; De Vos, A.; Akkermans, J.; Spurk, D.; Semeijn, J.; Van der Velde, M.; Fugate, M. Sustainable careers across the lifespan: Moving the field forward. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Maher, K.J. Alternative information-processing models and their implications for theory, research, and practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Akkermanse, J. Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R. Job longevity as a situational factor in job satisfaction. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.K.; Corley, K.G. Building better theory by bridging the quantitative-qualitative divide. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1821–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Wagner, E.L.; Tierney, P.; Newell, S.; Galliers, R.D. Datification and the pursuit of meaningfulness in work. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 685–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.H.; Rouse, E.D. Let’s dance! Elastic coordination in creative group work: A qualitative study of modern dancers. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1256–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, T.; Golden-Biddle, K.; Germann, K. Legitimizing a new role: Small wins and microprocesses of change. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 977–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canevello, A.; Crocker, J. Creating good relationships: Responsiveness, relationship quality, and interpersonal goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 99, 78–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, M.; Bamberger, P.; Shi, J.; Bacharach, S.B. The dark side of socialization: A longitudinal investigation of newcomer alcohol use. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nifadkar, S.S.; Bauer, T.N. Breach of belongingness: Newcomer relationship conflict, information, and task-related outcomes during organizational socialization. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J.P. Sensemaking under pressure: The influence of professional roles and social accountability on the creation of sense. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, P.; Noorderhaven, N.; Vaara, E.; Kroon, D. Giving sense to and making sense of justice in postmerger integration. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 256–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacharach, S.B.; Bamberger, P.; McKinney, V. Boundary management tactics and logics of action: The case of peer-support providers. Adm. Sci. Q. 2000, 45, 704–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, P.; Biron, M. Group norms and excessive absenteeism: The role of peer referent others. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 103, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J.; Wanberg, C.; Rubenstein, A.; Song, Z.L. Support, undermining, and newcomer socialization: Fitting in during the first 90 days. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1104–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhlbien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Bodner, T.; Erdogan, B.; Truxillo, D.M.; Tucker, J.S. Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Sluss, D.M.; Saks, A.M. Socialization tactics, proactive behavior, and newcomer learning: Integrating socialization models. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 70, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L.; Porfeli, E.J. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Career adaptability: A meta-analysis of relationships with measures of adaptivity, adapting, responses, and adaptation results. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nifadkar, S.S.; Tsui, A.S.; Ashforth, B.E. The way you make me feel and behave: Supervisor-triggered newcomer affect and approach-avoidance behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1146–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, J.N.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Van Ginkel, W.P. The catalyst effect: The impact of transactive memory system structure on team performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1154–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerpott, F.H.; Lehmann-willenbrock, N.; Voelpel, S.C.; Vugt, M.V. It’s not just what is said, but when it’s said: A temporal account of verbal behaviors and emergent leadership in self-managed teams. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 717–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Jia, L.; Takeuchi, R.; Cai, Y. Do high commitment work systems affect creativity? a multilevel combinational approach to employee creativity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, M.; Spears, R.; Watt, S.E. Visibility and anonymity effects on attraction and group cohesiveness. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, C.I.C.; Lanaj, K.; Ilies, R. Resource-based contingencies of when team-member exchange helps member performance in teams. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1117–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, S.M.; Van Dyne, L.; Kamdar, D. The contextualized self: How team-member exchange leads to coworker identification and helping OCB. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 100, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Liu, D.; Loi, R. Looking at both sides of the social exchange coin: A social cognitive perspective on the joint effects of relationship quality and differentiation on creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1090–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B.; Earley, P.C. Collective cognition in action: Accumulation, interaction, examination, and accommodation in the development and operation of group efficacy beliefs in the workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 438–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tost, L.P.; Gino, F.; Larrick, R.P. When power makes others speechless: The negative impact of leader power on team performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1465–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffiee, J.; Byun, H. Revisiting the portability of performance paradox: Employee mobility and the utilization of human and social capital resources. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 63, 34–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W.; Nijstad, B.A.; Van Knippenberg, D. Motivated information processing in group judgment and decision making. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 12, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, T.B.; Tesluk, P.E.; Marrone, J.A. Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1217–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Serban, A.; Roberts, A.J.B. Exploring antecedents and outcomes of shared leadership in a creative context: A mixed-methods approach. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Hamel, G.; Mol, M.J. Management innovation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberda, H.W.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.; Heij, C.V. Management innovation: Management as fertile ground for innovation. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2013, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggitti, P.G.; Smith, K.G.; Katila, R. The complex search process of invention. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Maggitti, P.G.; Smith, K.G.; Tesluk, P.E.; Katila, R. Top management attention to innovation: The role of search selection and intensity in new product introductions. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 893–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katila, R.; Chen, E.; Piezunka, H. All the right moves: How entrepreneurial firms compete effectively. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2012, 6, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagni, A.; Mele, V.; Ravasi, D. How early implementations influence later adoptions of innovation: Social positioning and skill reproduction in the diffusion of robotic surgery. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 242–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, D.A.; van Knippenberg, D.; Wisse, B. The role of regulatory fit in visionary leadership. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, D.; Lord, R.G.; van Knippenberg, D.; Wisse, B. An image of who we might become: Vision communication, possible selves, and vision pursuit. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 1172–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmelly, R. Innovation for emerging markets confronting institutional environment challenges: Perspectives from visionary leadership and institutional entrepreneurship. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 11, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F. Managerial Attributes, Incentives, and Performance. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1680484 (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F. An Empirical Assessment of Empirical Corporate Finance. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1787143 (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Giroud, X.; Mueller, H.M. Corporate governance, product market competition, and equity prices. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 563–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F. Mutual monitoring and corporate governance. J. Bank Financ. 2014, 45, 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F.; Wang, Y.A. Industry Tournament Incentives. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2018, 31, 1418–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Lin, S.; Sun, S.; Tucker, A. Risk-Adjusted Inside Debt. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 35, 12–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, J.; Guay, W. The use of equity grants to manage optimal equity incentive levels. J. Account. Econ. 1999, 28, 151–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Career Level | Industry | Recommendation Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Director | Manufacturing | Indirect social network |

| A2 | Vice Director | Consulting | Direct social network |

| A3 | Director | Financial | Indirect social network |

| A4 | Vice General Manager | Real Estate | Indirect social network |

| A5 | Director | Real Estate | Indirect social network |

| A6 | Vice General Manager | Food | Direct social networks |

| A7 | Director | Medical Service | Indirect social network |

| A8 | General Manager | Financial | Indirect social network |

| A9 | Vice Director | Financial | Direct social network |

| A10 | Director | Real Estate | Indirect social network |

| A11 | Director | Hotel | Indirect social network |

| A12 | Director | Technology | Direct social network |

| A13 | Director | Jewelry | Indirect social network |

| A14 | Director | Cosmetic | Indirect social network |

| A15 | Vice General Manager | Consulting | Indirect social network |

| A16 | Vice President | Chemical | Direct social network |

| A17 | Vice General Manager | Tourism | Direct social network |

| A18 | Vice General Manager | Chemical | Direct social network |

| A19 | Director | Chemical | Indirect social network |

| A20 | Vice Director | Financial | Indirect social network |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Q.; Xue, Y. Sustainable Career Development of Newly Hired Executives—A Dynamic Process Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083175

Li Y, Li X, Chen Q, Xue Y. Sustainable Career Development of Newly Hired Executives—A Dynamic Process Perspective. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083175

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yuan, Xiyuan Li, Qingmin Chen, and Ying Xue. 2020. "Sustainable Career Development of Newly Hired Executives—A Dynamic Process Perspective" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083175

APA StyleLi, Y., Li, X., Chen, Q., & Xue, Y. (2020). Sustainable Career Development of Newly Hired Executives—A Dynamic Process Perspective. Sustainability, 12(8), 3175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083175