1. Introduction

Concepts like inclusive planning [

1], participatory place-making and co-design city making [

2,

3,

4], engaged urbanism [

5], the city of well-being [

6], the sustainable city [

7,

8], the just city [

9,

10], and right to the city [

11], have gained traction since early 2000s. They are all premised on a need to redress relatively unfair and inequitable decision-making in urban planning, labelled as a democratic deficiency [

12]. To counter this, planning has been recast as a dynamic and fluid process that needs to be constantly adapted to the interactions between ‘people, place and capital flows’ [

13] and greater focus has been given to the involvement of stakeholders in this process.

Within this context, collaborative planning has been presented as a critical component of addressing the challenges currently seen as confronting planning in general and urban design and regeneration in particular. Sustainable urban development, for instance, has long been held to require a degree of self-determination, in the form of people actively participating in making decisions that affect their lives. Since the Rio Earth Summit [

14], continued emphasis has been placed on the need to develop more democratic mechanisms for making decisions and policy implementation [

15,

16]. Accordingly, Humphreys [

17] suggested that, if planning is to serve the public’s interest and account for the consideration of sustainability issues—such as environmental responsibility, economic productiveness and climate resilience—then it should establish clear parameters for action, indicating what is recommended or desirable from a social, environmental and cultural perspective, and what should be avoided. This suggestion is based on the view that collaborative planning needs to be employed as a negotiating tool aimed at seeking compromises or integration between issues, policy sectors and actors.

Involving people in effective forms of collaborative participation is now being presented as going beyond making minor modification to plans. Instead, it is about providing equal and fair access to collaborative activities, and about accommodating differences, while minimizing power distortions, (see

Figure 1). However, as Cooper [

18] has pointed out, it can be very difficult to get trained professionals to accept that local stakeholders’ lived experience is a legitimate basis for making decisions about interventions in the built environment, let alone get them to grant it parity of esteem with their own expertise.

Design-led planning events, which are one approach to enhancing engagement, characteristically involve members of a community working alongside local authorities and developers and other stakeholders to co-create visually planned, agreed strategies and an action plan [

19]. Such events are being increasingly adopted worldwide [

19,

20,

21,

22] and have become accepted practice in Scotland [

4].

This paper draws on research undertaken for the Scottish Government: ‘Shaping better places together: Research into facilitating participatory placemaking’ [

4]. This research was undertaken to explore new ideas and insights into the facilitation of design-led events, based on recent experience drawn from across Scotland and beyond. The project sought to begin to build an empirical base for exploring and critically evaluating the wider discourse in collaborative planning about where, when and how to use engagement opportunities—a topic being actively discussed within both practice and academia. The paper begins with a literature review of the collaborative planning and design-led approaches to set the context, and this is followed by an outline of the methods employed for collecting data in the research. It investigates the experience of professionals and other participants in design-led events in Scotland. Analysis of this experience forms the basis for the discussion and conclusions.

2. Design-Led Events

There has been wide support in the literature over the last two decades for more communicative and collaborative approaches to planning through some form of more participatory democracy [

2,

15,

19,

20,

21,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Almost two decades ago, Allmendinger [

34] suggested that this move should be considered as more than just another planning theory—instead, it should be seen as a new and improved ‘world view’ that planners and other stakeholders need to adopt.

Design-led planning events, which typically involve stakeholders in collaborative decision-making about their built environment, come in many shapes and sizes. At one end of the scale, public and private sector bodies have arranged events simply as a cursory means of obtaining comments from residents. Such practice only seeks responses to tick boxes or to ‘engineer’ planning consent or agreement on the principles of a local plan, resulting in processes that are top-down or one-way. As Arnstein highlighted 50 years ago in her ladder of participation [

35], such practices can be labelled as consultation, a merely token form of engagement. At the other end of the scale, there are projects that are set up and co-designed, for example by social enterprises, that operate through a ‘bottom-up’ approach. There are also more imaginatively focused events, such as citizen-led initiatives, that seek to generate ideas, comments and information directly from the involvement of local community members [

20].

As described in the literature, details of the techniques employed for design-led events and of their outcomes will vary, dependent on the context, purpose and sponsors involved. Promoters may be private developers, public agencies, landowners or non-governmental agencies [

36]. Their particular form and focus will be dependent upon who initiates and sponsors them, on their specific purpose and objectives, and on whether the event is treated as being stand-alone or embedded in the broader process of collaborative planning [

2,

19,

20]. There are examples of organizers and facilitators of design-led events being blamed for operating within a framework that favors the sponsor’s interests (particularly those of private developers or local authorities) over those of local communities [

20]. Such critics advocate an honest and mutually empowering relationship with locals and ‘end users’, through ongoing dialogue, to augment the relevance of interventions [

20] (p. 76); see

Figure 2.

The literature on such design-led events, although acknowledging they are embedded in a wider process, tends to discuss them as if they were one-off or stand-alone activities [

2]. In this paper, the authors argue that such events should not be viewed alone; rather, they need to be seen as part of on-going conversations with communities and relevant stakeholders to help to show progress, to explain and implement decision-making, and to demonstrate that stakeholders’ contributions are making a difference. In the literature reviewed, this distinction between collaborative planning as an ongoing process and design-led events as a stage in that process is not consistently observed. Instead, for instance, charrettes—the most prominent form of design-led events being practised in the UK—are frequently described (see below) as being a design process in themselves, rather than as a particular stage within a larger, continuing planning process.

Charrettes have become associated with the term ‘co-production’, which has been borrowed from the field of public services policy [

37] (p. 719) in order to describe a more effective and cost-efficient transformation of decision-making through the involvement of users in the design and delivery of these services [

38,

39,

40].

Seen from this perspective, in order to be effective, collaborative planning depends on: (a) integration and synergy across professional disciplines, (b) across the multiple strands that make up the collaborative planning process, and (c) between their interwoven stages [

2,

19,

20]. It also requires building trust and common purpose between team members and local stakeholders from a wide range of backgrounds and constituencies, with widely divergent concerns and (vested) interests. Ideally, the aim of collaborative planning is promoted as being to engender a collective understanding of the places where interventions are planned through dialogue and deliberative participation [

26]. Where such agreement cannot be reached, its purpose is described as being to bring about explicit and acceptable negotiations about how to proceed,

Figure 3. Enabling this collaborative dialogue, and then empowering the implementation of its resultant co-decision-making, are essential skills required of the team commissioned to facilitate design-led events [

2,

4].

There is, however, evidence from planning literature of a prevailing gap between participation rhetoric in policies and participation as practiced at the operational level [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. For example, although the literature stresses the importance of the ‘pre, during and post-event stages’ [

2,

28,

36,

47,

48] as part of the larger, on-going planning process, there are few signposts to (a) exactly what these stages entail; (b) where, when and how the professionals’, lay stakeholders’ and facilitators’ contributions are most effectively deployed; or (c) how they should be embedded in broader collaborative planning as a continuing process. However, if explicit articulation of the contributions that need to be made in the multiple stages involved is not spelt out, there is a risk of creating barriers to communication across different sectors, reducing trust and confidence, leading ultimately opposition to both the planning process and to its outcomes. Grappling with this problem is timely given the endorsement that collaborative planning in general, and design-led events in particular, are receiving from some governments [

2,

31].

This paper is focused on making the case for giving greater attention to the requirements that have to be met at each of six stages of the collaborative planning process reported below. Individual attention to each of them is necessary to ensure that the involvement of the public produces real, authentic and tangible benefits [

46] as a means of sharing evidence of what is seen as ‘good practice’ in collaborative decision making. However, stakeholder participation in design is a good example of planning complexity [

49], where fragmentation, uncertainty and ‘social problems’ are compounded by a multiplicity of stakeholder views. Here, the resultant complexity needs to be understood as socially constructed, as arising from contradictions inherent in this diversity of opinions and interests, rather than as just being as the product of complicated (bureaucratic) processes.

Due to the complexity of contending forces described, there is no single paramount paradigm around which to organize thought and action in this arena. Instead, there are competing viewpoints about how best to deliver collaboratively based, design-led events and, indeed, about how much priority should be given to them in the collaborative planning process. This complexity and disagreement point to an urgent need for a coherent, strategic approach to collaborative planning and design, including more explicit articulation of the stages involved in the parallel strands of activity required for effectively delivering design interventions in the built environment, accompanied by clear specifications of the contributing roles and responsibilities of those involved in each stage in this highly complex process. This paper attempts to begin to assemble an empirical base for addressing this need.

4. Comparing Advice in the Literature with Participants’ Experience

The descriptions which follow are based on highlights drawn from the full report of the study undertaken on behalf of the Scottish Government [

4]. In addition to the review of the literature, this contains detailed reporting of analysis of the quantified results of the survey accompanied by a qualitative analysis of individual comments and group/plenary discussions at the follow-up interactive workshop held to scrutinize the survey results. The sections which follow first summarize received opinion about design-led events drawn from the academic literature in order to then compare this with the reported experience of those who have taken part in them.

4.1. What the Literature Suggests

In the literature, the extent to which the public is to be involved at different points in design-led events—as in collaborative planning as a whole—is a matter of some debate. This has practical implications for the work of those running such events. Some have suggested that no two design-led events are ever the same [

19,

28,

29], and, therefore, each should be designed in a bespoke way. Conversely, Lennertz and Lutzenhiser [

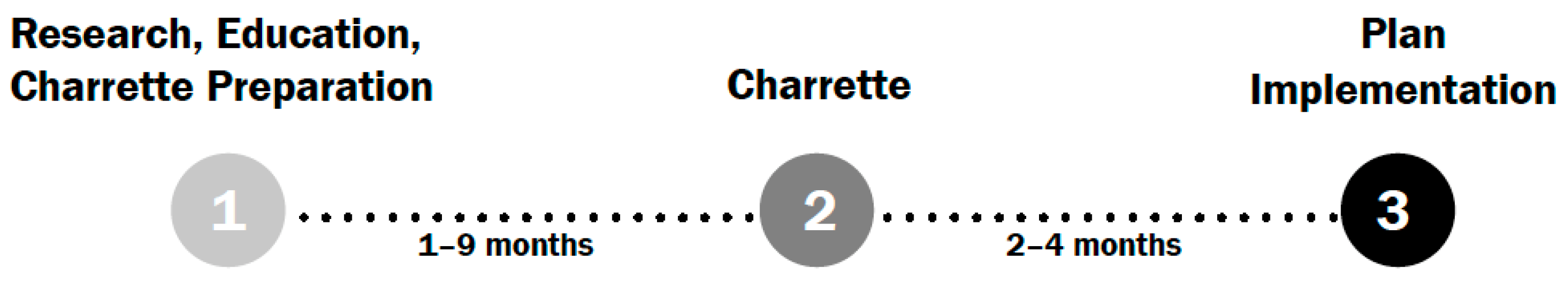

36] pointed out three (universally) important stages in the organization and deployment of such events, as shown in

Figure 5 for a charrette, for example.

These stages are related to specific practical tasks: (1) information gathering (pre-event); (2) intensive face-to-face collaboration (at design-led events); and (3) implementing outcomes and follow up (post-event). In practice, the significance of these stages will depend in part upon the purpose of each individual event. Yet, in the literature reviewed, there is little guidance even as to the basic steps needed for preparation in Stage 1 or for the implementing resulting outcomes from design-led events in Stage 3.

In the literature, the pre-event stage is seen [

53] as particularly important preparation for: (a) finding the correct meeting place, materials and staff [

28]; (b) devising inclusion strategies which counteract cultural and knowledge imbalances affecting participation and capacity building [

54] (p. 209); (c) publicizing the event to make it as inclusive as possible with widely circulated advance notification; and (d) determining who should be participating in addition to the wider public (e.g., policy experts and specialists). Stakeholder outreach activities might be undertaken, e.g., for local schools [

19] or through outdoor activities or social gatherings, in order to help connect to a community or group members through emotional intelligence rather than a generic ‘informational approach’ [

20]. Although these activities are presented as running linearly in the literature (as reflected in this paper), this simplification is only used here to make them more easily intelligible. In reality, they are likely to be less clear-cut, indeed much more entangled, with potential iterations or overlaps between them.

At the design event itself, the underlying and guiding intention is said in the literature to be ‘co-production’ as far as this is possible, with the local community members and other stakeholders involved [

19,

22,

47]. This step is deemed to be essential for effective facilitation and relies on successfully creating a ‘holding environment’ where a web of relationships with stakeholder groups is secured and where, ideally, people are in active partnership through an agreed sharing of resources and decision-making responsibilities [

47]. To achieve this, local stakeholders are to be accepted and treated as ‘integral to place development and as partners in the processes of co-creation, co-ownership and co-evolution of plans and proposals rather than mere users or clients of services’ [

55]: (p. 15).

In the literature reviewed, when evaluating outcomes of collaborative design events, emphasis is placed on the imperatives, techniques and tools employed, and on the quality of implementation, and on their resulting outputs [

19,

56]. Tools and techniques should be used, it is argued, to build the necessary trust and understanding before any design interventions are carried out [

20]; see

Figure 6.

Although less discussed, both pre-and post-event stages are also seen as being essential to achieving the goals described above [

36,

57]. Holding a follow-up post-event session is signposted as being good practice to demonstrate progression and explanation of decision making [

28,

36,

47] and for illustrating that participants’ contributions have made a difference [

19,

28,

47]. Hence, the advice that a “charrette is only as good as what happens after” [

28] (p. 112). Once an event is completed, the process is “far from over”, and it is seen as critical that momentum is kept through its completion [

36]. All too often, however, charrettes are seen as concluding with no clear plans as to how to transform the design ideas generated into the policies necessary to implement them [

28] (p. 112). Instead the stated aim here is to transfer ownership of the process to the stakeholders involved, so that it appears legitimate to those who have taken part. This is presented as ‘building capacity’ and putting in place a governance structure in partnership with a local community, so that they can take some of the identified steps forward themselves [

19,

31,

52]. Despite the importance attached to it, there are few signposts in the literature as to what the post-event stage entails. Continuing participation might take the form of community forums, engagement in the production of planning documents and planning applications, or membership of delivery vehicles, such as town teams or community trusts [

19].

4.2. What Event Participants’ Experience Suggests

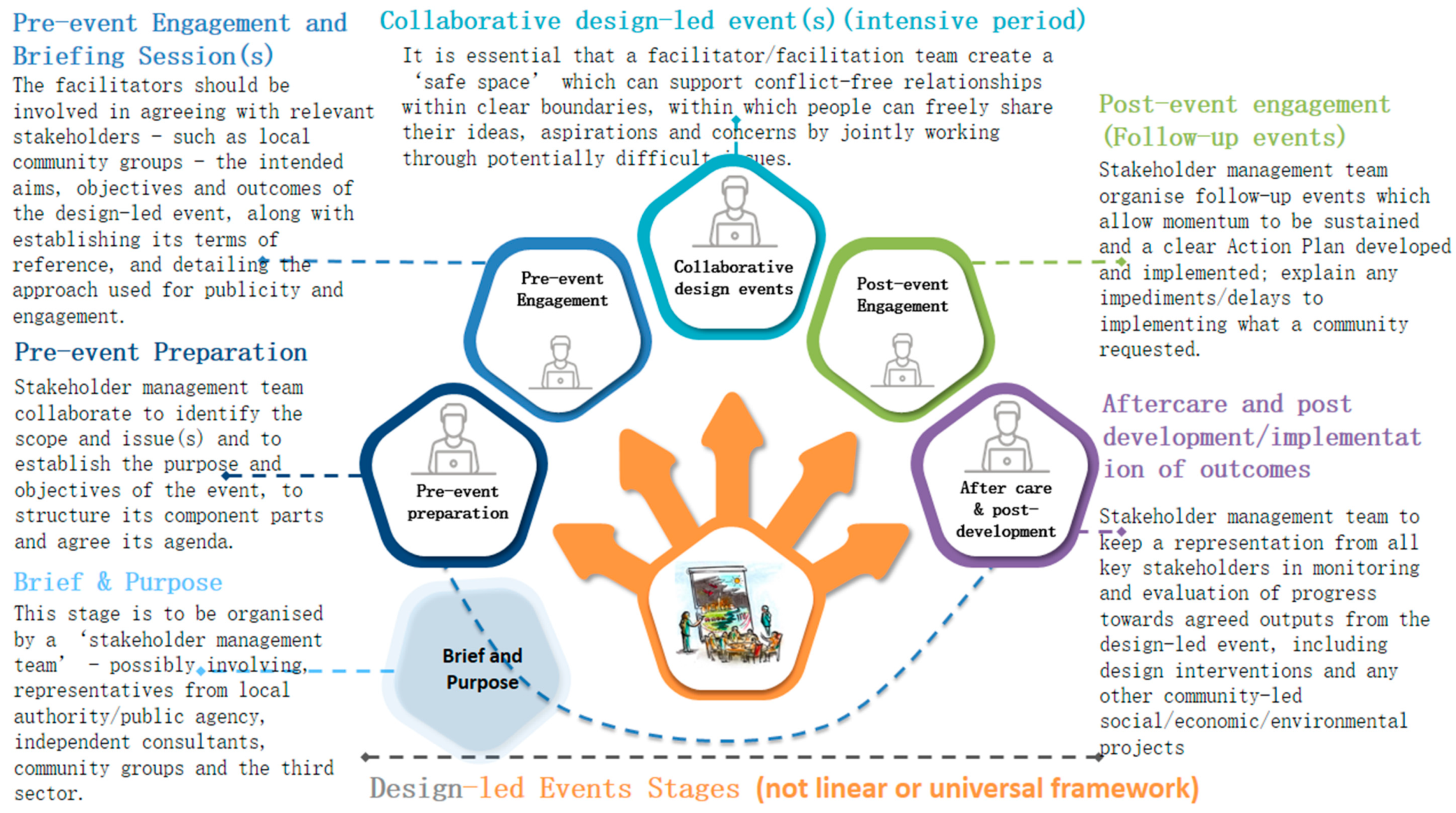

While the literature portrays three (albeit entangled) stages for undertaking design-led events, our Scottish survey respondents identified the need for twice as many; see

Figure 7.

Figure 7 was distilled by collating and analyzing the responses received from those who took part in the survey. The accuracy of this depiction was then offered for evaluation by those who had taken part in the survey through discussion of it at the follow-up interactive workshop. This discussion indicated that participants in the study agreed that stakeholder involvement in collaborative decision making about interventions in the built environment does need to be supported through a more highly elaborated description of three additional key stages to the three previously described in the literature (see

Figure 5 above). Each of these six stages is now discussed in the light of what participants suggested they should contain.

4.2.1. Stage 1: Brief and Purpose

These activities are held to be necessary by participants in the study to instigate stakeholder engagement, for identifying the issues to be addressed, for deciding on the type of processes and activities to be used for addressing these issues, and for developing a funding and resourcing proposal.

“Clear briefing and guidance from the owners of the design led event is crucial. This should be an iterative process with the design team to ensure that the proposed outcomes are clear and that any key issues to be addressed are fully understood”.

(professional)

A brief needs to be refined with the client, with those responsible for managing input from stakeholders, and with the team delivering the design intervention, in order to ensure buy-in across all stakeholder groups.

This stage, as described by participants, is to be organized by what can be labelled as a ‘stakeholder management team’—possibly involving, in Scotland at least, representatives from local authorities/public agencies, independent consultants, community groups and third sector organisations.

“Briefing sessions should be used to bring on board any relevant stakeholder groups who may have views based on previous experience of consultation or participative exercises”.

(lay participant)

Elsewhere (where design-led events are more market-driven than public-sector-driven), Stage 1 may be carried forward by developers keen to bring local stakeholders on board in order to expedite planning permission.

4.2.2. Stage 2: Pre-Event Preparation

This stage builds on output from the previous one. It is as seen by by survey respondents as being organized by a stakeholder management team—possibly with support from members drawn from those commissioned to facilitate the up-coming design-led event. It differs from the previous one by enrolling representatives of other key stakeholder groups identified in Stage 1. These actors collaborate to identify the scope and to establish the purpose and objectives of the event (including understanding any boundaries/limits), to structure its component parts and to agree its agenda.

“Pre-event preparation is important to establish the terms of reference for the event and to tune the approach to engagement in dialogue with local people”.

(professional)

At this stage, an event should be inclusively publicized by widely circulated advance notice to identified stakeholder groups. These need to extend beyond the wider general public to include policy experts and specialists.

In the survey, almost all event participants (91%) reported that they received pre-event publicity outlining the aims and objectives of the event they had attended. However, only 78% thought this information had been clear. Whilst the majority of participants (69%) said they were clear about the objectives of their design-led event, a sizable minority (31%) felt that these stated objectives did not address the real issues and concerns affecting their community. Further, 16% of them reported that their facilitation team had inadequate ‘local knowledge and expertise’ to successfully guide the participatory design process.

4.2.3. Stage 3: Pre-Event Engagement and Briefing Session(s)

The aim of this stage, according to participants, is to break down barriers to engagement by providing clarity to all those due to take part about the purpose of the event and how they can contribute constructively to its activities. This stage differs from Stage 2 by offering the facilitation team an opportunity to explain and set realistic parameters from the outset, which help to manage expectations later in the collaborative planning process.

“Those commissioning an event (funders, local authorities, community councils) need to be clear about the constraints and limitations affecting it and to make these explicit to all those invited to participate”.

(professional)

Early introduction of issues to stakeholder groups prior to an event gives them time to think about the issues and begin to formulate ideas which can be built on at the event.

Participants in the study argued that facilitators should be involved here in agreeing with relevant stakeholders—including local community groups—the intended aims, objectives and outcomes of the design-led event, along with establishing its terms of reference, and detailing the approach used for publicity and engagement. They should also discuss any practical issues surrounding what may be anticipated within the follow-on steps. The purpose here is to strengthen the capacity of non-professional stakeholders to contribute effectively to the design-led event. Some also argued that, in the pre-event briefing sessions, any legal, policy and procedural factors should be explained as well as the status of any other recent consultation exercises along with relevant data about an area already available.

Over half (53%) of the event participants indicated that, at their event, practical constraints (e.g., money, time, resources, etc.) had been clearly explained at the outset, enabling them to realistically engage in the design and decision process. However, a significant minority (33%) said that these constraints were not clearly explained and a further 14% were ambivalent in their views. This suggests that much needs to be done to explain to participants what can be realistically achieved by such events in order to manage stakeholder expectations.

“… a briefing beforehand would most definitely be beneficial to set aside pre-conceived views”.

(lay participant)

Concern was also expressed that pre-determined agendas were being pursued by local authority planning departments, their consultants or other stakeholder groups. And there was also a perception that decision-making was dominated by professionals.

A large majority (73%) of event participants responded that facilitators made good efforts to engage with ‘young people’, those ‘seldom heard’, and ‘hard to reach’ stakeholders.

“Briefing sessions to explain purpose—and practical limits/influences—are very useful—and their absence weakens the events”.

(professional)

“Briefing sessions should be used to bring on board any relevant stakeholder groups who may have views based on previous experience of consultation or participative exercises”.

(professional)

Additionally, they welcomed the current practice of pre-event engagement, which takes the message out into the community and employs innovative methods to connect with different stakeholders in their own settings and on their terms.

“A briefing session can be good in determining how to structure the main event”.

(lay participant)

4.2.4. Stage 4: Collaborative Design-Led Event(s)

There appeared to be general agreement amongst the event participants that, during this stage, it is essential that a facilitator/facilitation team create a ‘safe space’ which can support conflict-free relationships within clear boundaries, within which people can freely share their ideas, aspirations and concerns by jointly working through potentially difficult issues. Equally, during design-led events, a facilitator is seen as having a responsibility to help the participants develop meaningful actions or forward momentum, and not just to have open-ended conversations. Facilitators need to help construct routes forward, and not simply interpret the past or build a lowest-common-denominator consensus. Participants should be able to understand clearly and follow how their comments, opinions and ideas contribute to the process underpinning the event and to its outcome. Event participants consider good communication skills as essential. However, their reported priority is that facilitators take the time and effort to listen attentively to participants in order to understand their concerns.

Some participants suggested that facilitators need a degree of knowledge of design and planning processes (e.g., funding bids) and potential outcomes—or that they should ensure that other participants in an event have this expertise—in order to assist community members in constructing a way forward.

The majority (84%) of event participants reported that their facilitators had made an effort to use plain English, and 82% of them suggested that their facilitation team had encouraged honest, informal, open conversation between different stakeholders. However, only a minority (21%) reported that they were really listened to, and, whilst most them identified facilitators who had managed specific groups-that had tried to dominate or avoid meaningful discussions-fairly well, others indicated that there was room for improvement here.

“The format of the event [needs to be] properly designed-ensuring all parties will be able to feel they can understand the process and contribute effectively”.

(lay participant)

Less than half (48%) of event participants reported that conflicting opinions aired during the engagement process were effectively explored and resolved with the help of the facilitation team and a not insignificant minority (12%) said they were not. The remainder were more ambivalent in their responses here. This suggests, given the emphasis that event participants placed on ‘seeking inclusive solutions’ as an essential facilitation skill, that this is an area in need of greater attention.

“A successful event should leave a community and authorities with a clear idea of who is responsible for taking forward any actions identified”.

(professional)

Once a design-led event is underway, the role of the facilitator is seen as being to maintain an overview of both the design process and group dynamics, and to both guide and intervene where necessary. Part of this role is to ensure that the timetable is followed, but it may also be necessary to be flexible and to decide whether it may be beneficial to deviate from the timetable, for example to give people more time, or to bring everyone together to address a particular issue that may have arisen.

“Facilitators should adopt a neutral stance yet put a ‘sense check’ on the aspirations of a community groups to manage their expectations of what can realistically be delivered”.

(professional)

4.2.5. Stage 5: Post-Event Engagement (Follow-Up Sessions)

The aim of follow-up sessions, as described by event participants, is to transfer ownership of the implementation of the desired outcomes, identified at the design-led event, to the stakeholder groups involved, as far as this is possible. This transfer has to be genuine to build sustainable capacity within the groups and depends on the adoption of an effective governance structure. There were participants that argued this stage should ideally be organized by a stakeholder management team. Keeping a facilitator on board might be helpful but is not necessarily seen as being essential to ensuring momentum on actions and desired outcomes agreed at the design-led event. To maintain stakeholders’ confidence and trust, it is seen as important to report progress and explain any impediments/delays to implementing what a community requested. Achieving this may require a stakeholder management team to work with and through delivery groups that lie beyond the planning system.

A majority (69%) of event participants considered that all the key decisions made at their design-led event were accurately represented in its final report (which should include a clear summary of ideas and a plan of action to take these forward). But about a fifth (19%) were more ambivalent in their responses, and more than tenth (13%) were unsatisfied with the content of theirs. Having seen the final report of their event, more than two-thirds (69%) reported that their contribution to the process had been meaningful. But a fifth (18%) were non-committal and more than a tenth (12%) reported that their involvement had not been meaningful. The reported success of design-led events was lower when participants were asked to consider how meaningful input from the community as a whole had been. A small majority (57%) reported that it had been, nearly a third (30%) gave more ambivalent replies and, again, more than a tenth (12%) said that it had not.

More than half (59%) of event participants had previously suggested that greater involvement of the lead facilitator in early discussions about events would be beneficial in tailoring the proposed participatory design process to the specific needs of the community being involved.

And three-quarters of them (75%) also indicated that continued involvement of a lead facilitator in follow-up events would be beneficial to the community in terms of build momentum, kick-starting a stalled action plan, or creating active stakeholder groups.

“Post-event involvement is important to guide implementation, particularly with public body stakeholders”.

(professional)

“Follow-up events are essential to build up (on) any trust that the events may have generated. To miss out this step loses lots of goodwill and knowledge, as we have seen on many occasions”

“The follow-up session allows the participants to see their ideas represented and would hopefully encourage them to participate in future community discussions”.

(professional)

“Participants need to know what is going to happen to deliver any identified outcomes, with a clear sense of direction and timings established”.

(lay participant)

4.2.6. Stage 6: Aftercare Post-Development/Implementation of the Outcomes

Some participants suggested that this stage is similar to the previous one, in that it ideally should be organized by a stakeholder management team, Although the presence of a facilitator might be helpful, this was not viewed as essential. However, the purpose of this stage is to maintain representation from all key stakeholders during monitoring and evaluation of progress towards agreed outputs from the design-led event, including design interventions and any other community-led social/economic/environmental activities arising from it.

“Aftercare sessions are absolutely essential in keeping momentum going on the actions agreed through the participatory design event and also in ensuring that the event itself is realistic in defining which suggestions are achievable and which are only aspirational”.

(professional)

“This includes monitoring and evaluation of the achievement of design intervention goals (such as monitoring the delivered quality of decisions and outcomes as a measure of performance over time). This requires the development of solid key performance indicators (KPIs) and monitoring techniques that reflect measurable impacts”.

(professional)

This area requires more research, review and thought around effectiveness and best practice.

4.3. Recognising Professional Actors’ Roles and Responsibilities in the Six Stages

Those involved in running design-led events need to clearly understand their intended roles and contributions. In the literature reviewed, academic researchers clearly share concerns about:

Who gets involved in making decisions that underpin design-led events;

What constitutes relevant knowledge for doing so;

The role of facilitators and other key stakeholders in achieving this.

During the interactive workshop, the survey respondents who attended it agreed that there is possible confusion over stakeholder responsibilities during the six stages surrounding a design-led event, each of which involves a different mix of actors. While each of the six stages listed above has distinct tasks to deal with, in practice there may be crossover between them. Moreover, each stage depends on those that have preceded it to foster continuity and to enable progress towards the desired overall outcomes of collaborative planning.

“Recognise there are different stakeholder responsibilities in operation—clarity is needed about the specific support that each team requires”.

(professional)

The study distinguished between three key groups of professional actors that are engaged in the six stages. Importantly, some of them function as members of a time-limited task force (those delivering the facilitation function), while others operate on a more continuous basis, staying in post before and after such events (those supporting stakeholder engagement).

Between them, those who took part in this study identified three separable but, in practice, highly interwoven strands involved in delivering collaborative planning; see

Figure 8.

(A) Stakeholder management strand: a series of activities for enrolling stakeholders in collaborative planning. This strand includes those professionals who want/need/desire to be comfortable communicating with and in front of local stakeholders. Survey responses indicated that:

“these may work for clients, or for planning, housing, development project management, or may come from architecture and design, or even from the art world”.

(professional)

The actors involved in this strand of activity often pre-exist any planned collaborative design-led event and may continue to play a role in engaging stakeholders long afterwards.

(B) Facilitation strand: a series of activities required for mounting design-led event(s), typically undertaken by a scratch ‘facilitation team’. Its members may be drawn from the stakeholder management team and/or from the team of those responsible for the design intervention in question, probably supplemented by an (un)trained facilitator.

“Important to recognise the time-limited, task force nature of the facilitation role”.

(professional)

(C) Design strand: a series of activities undertaken by members of a design team, which may comprise architects, landscape and urban designers, engineers, transport and infrastructure planners, neighborhood and environmental planners, and sometimes economic and cost planners, as well as heritage and cultural specialists. Their level of involvement depends on what they are asked to do by those mounting a design-led event. The scope of their contribution depends on the brief and challenge they are given. They can be independent consultants; members of local authorities, public agencies, or the third sector; or may include volunteers, e.g., students.

Respondents to the survey reported that, in practice, a facilitator’s role can be, and often is, restricted solely to the ‘during the event’ stage. Sometimes, they are involved, to a lesser extent, in the ‘before’ and ‘after’ stages. Collating the experience of those who have taken part in design-led events points to facilitation having a contribution to make across all six stages, particularly in terms of providing the soft people-management skills required both to empower stakeholders to enable them to play a role in decision-making and to keep them on-board while these decisions are being followed through. Whether facilitators’ continued involvement is necessary strongly depends on the extent to which these people management skills can effectively be delivered by the client and/or other professionals involved in their absence.

The verbatim statements cited above, made by professional and lay participants, indicate that they have different priorities for design-led events. Comments from professionals suggest that they were concerned about how such events are conducted and about their governance. Lay participants’ comments point to them being more pragmatic—as being concerned with the outcomes of such events, with the delivery of these on the ground, and with who is responsible for their implementation during the follow-on.

6. Conclusions

The significance of this paper lies in its report of an attempt to begin the construction of an empirical base for exploring the conduct of design-led events, which has, up until now, been lacking. This report is intended as a valuable contribution not just to the academic literature on such events but to how this component of collaborative planning is operationalized in practice. But the research reported has limitations. First, the results recorded are dependent on self-reporting from those who have experienced design-led events and, as a result, it may be colored by the specific preferences and prejudices of the relatively small sample canvassed. As a consequence, the results reported cannot be overgeneralized. Instead, the results are context-specific, limited to what has been happening in Scotland, where promotion of such events has had central and local government sponsorship. This may also have colored the responses collected. Experiences in other countries may differ, especially where design-led events are initiated by private sector bodies, such as developers or landowners, and thus may be driven by other interests and priorities. As a result, events run in those circumstances may be qualitatively different—if not in form, then in focus and emphasis—to those that are government-inspired. Accordingly, participants’ experience of and views about them may also be different. Further research is required to provide empirical evidence to clarify such differences.

Despite these limitations, however, some generalizations seem legitimate. If only because their given situations and contextual circumstances will vary, there is unlikely to be a one-size-fits-all set of guidelines for such events. Furthermore, because of the need to react to changing conditions and timescales, the stewardship of collaborative planning in general, and outcomes of design-led events in particular, cannot be left to rest with a ‘single hand’, however ‘responsible’ this may appear. A wider network of shapers and framers, and of contributing stakeholders, is required, which is more inclusive—brought together by enrolling and empowering members of the local residential community, business, and voluntary groups, to engage in decision-making about interventions in their built environment.

In this paper, there has been a dual focus of attention on collaboration as a process and on outputs (intended to lead to stakeholders’ desired outcomes of design-led events) seen as the products of such collaboration. To date, as both the literature and the reported survey attest, far less attention has been given to monitoring or evaluating whether implementation of the outputs has actually delivered the outcomes desired, especially when seen from the as-lived experience of local stakeholders. However, tangible delivery and real follow-through changes are crucial to the effectiveness of design-led events as a worthwhile contribution to collaborative planning. Events that are successful on the day may risk a negative effect if subsequent non-delivery of the expectations they raise leads to stakeholder disillusion, fatigue and even growing distrust. Follow-through, and attention to whether outcomes are eventually achieved, are ultimately the keys to success. This cannot be gauged simply from what occurs on the day but is made manifest across a longer time horizon.

The voices heard through the survey results and from the interactive workshop discussions can be interpreted as calling for a reconceptualization of the collaborative planning process. The experience of event participants requires a clearer definition of who needs to be involved in the planning of design-led events. In addition, our respondents wanted the significance and scope of what they saw as key stages in collaborative planning processes to be broadened, so that each of the stages required to execute design-led planning can be given specific attention. Additionally, they pointed not to the three stages discussed in the literature, but to six. Moreover, their voices suggest these six stages draw on contributions from three parallel strands of activity—design, stakeholder management, and facilitation—each delivered by a different (but probably overlapping) set of actors, and each operating over a different time scale.

The experience of event participants signals the importance of roles played in ‘before’ and ‘after’ stages of design-led events by those responsible for initiating and then maintaining engagement and enrolment of participating stakeholder groups in ongoing collaborative planning. Pre-event and post-event sessions are not trivial but vital components of this ongoing empowerment. All six stages identified in this paper—and not just the design-led event itself—require sufficient resources. In practice, these are often limited. Taking action may often default to members of the stakeholder management team alone. Where this happens, and this team does not have the skills required, then the planning process may lose its legitimacy, not least in the eyes of local, lay stakeholders.

Those managing such events (whether members of a design team or a stakeholder management team) were also seen as needing a clearer understanding of where, when, and how they are expected to contribute. Moreover, no matter how large the differences (of power, status, education, social capital) between stakeholders outside an event, within it, facilitators are being called upon to construct a safe space where, for instance, ‘truth can be spoken to power’, and where professionals’ expertise and lay people’s lived experience are both treated as valid negotiating currency.

These findings are also significant from a social sustainability perspective. They reveal that the public participation imperative signalled nearly three decades ago by the Rio Earth Summit cannot be met by simple, one-off, events intended to canvass stakeholders’ opinions at a single point in time. Instead, meeting this imperative requires longitudinal engagement with them throughout planning interventions in the built environment, which provides them with continuous opportunities to contribute to decision-making. This, in turn, draws attention to the importance of civic governance. The decision-making on which planning is based will lose its social legitimacy, of being ‘for all and by all’, if it is not regarded as inclusive. Design-led events are intended as mechanisms for harnessing dynamic forces that continually restructure the planning process as it unfolds. Adopting democratic governance structures that focus on optimizing sustainability outcomes, successful delivery and effective monitoring can help make trade-offs that are inevitably required both more robust and more legitimate. Achieving this requires a longitudinal and detailed action plan agreeing who is going to do what and when, with contributions from whom, and with what resources and, not least, on the basis of what authority, for the whole lifetime of planning intervention and the subsequent management of what is delivered.

By highlighting current thinking and recent practice, this paper is intended to enable those involved in managing design-led events—as well as those active more broadly in collaborative planning—by helping them to: (a) identify key unresolved questions; (b) confront their own underlying assumptions (not just their aspirations and concerns but their preferences and prejudices); (c) break down barriers between professionals’ and stakeholders’ decision-making; and (d) assist placemaking by encouraging more reflective and deliberative planning practice. The issues, interwoven strands of activities, and their pitfalls identified by this research are complex. Just as in rope making, each strand—design, stakeholder management, or event facilitation—on its own may be relatively weak. Binding all three strands together so that they are more coherently and tightly interwoven will strengthen not just each one but the integrated contribution that they can make to the delivery of collaborative planning as a whole. More work is needed to understand how such integration can be achieved in practice—not just to improve facilitation but the roles that all professional and lay actors can play in collaborative decision-making about design interventions in the built environment.

Even just in relation to design-led events themselves, the research reported here gives rise to a plethora of, as yet, unanswered questions.

How can the appropriate breadth of stakeholders be enrolled and empowered early enough to engage in the framing and mounting of design-led events?

How can the critical pre- and post-event activities, on which the efficacy of design-led events clearly depends, be more robustly and appropriately resourced?

How can the results arising from such events be more effectively linked to post-event decision-making and delivery of interventions in the built environment?

What transitional support can be afforded to enable local and community stakeholders to take ownership of the post-event stages of collaborative planning process?

What legal status (legitimation) can be given, within the planning system, to the decisions and outputs (actions arising) agreed at design-led events?

What monitoring practices, including the establishment of shared and appropriate assessment and evaluation criteria, are necessary for gauging the impact of agreed goals and objectives arising from design-led events?

Answering these questions about just one strand in the activities required to deploy collaborative planning effectively will require assembly of a more robust evidence base concerning what, in practice, really works.