Evolution and Management of Illegal Settlements in Mid-Sized Towns. The Case of Sierra de Santa Bárbara (Plasencia, Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Evolution and Characterization of the Study Area

2.2. Analysis of Local Government Performance and Urban Policies Used for Illegality

3. Results

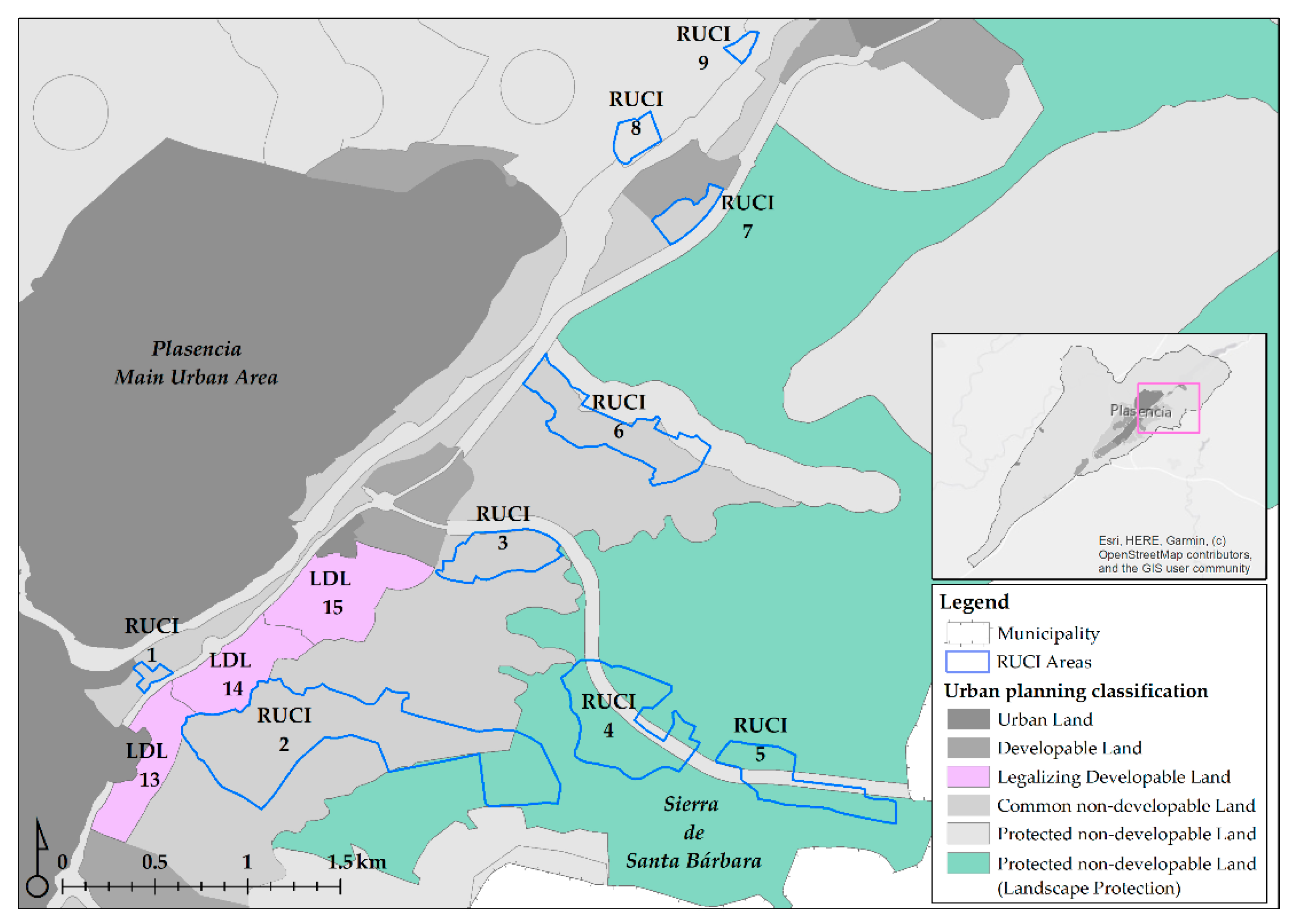

3.1. Study Area Characterization and Residential Evolution over Non-Developable Land (NDL)

3.2. Measures and Attempts of Urban Legalization

3.2.1. LDL, an Irreversible Urban Integration

3.2.2. Regulatory Proposal in the NDL and Its Feasibility

- (a)

- Allow legalization through RUCI areas in the “landscape protection NDL”.

- (b)

- Allow legalization through RUCI areas over the entire NDL.

- (c)

- Change the “landscape protection NDL” classification to “common NDL”.

3.3. The Municipal (City Council) Point of View Regarding Illegality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfaro, P.; Smith, H.; Álvarez, E.; Cabrera, C.; Fokdal, J.; Lombard, M.; Mazzolini, A.; Michelutti, E.; Moretto, L.; Spire, A. Interrogating informality: Conceptualisations, practices and policies in the light of the New Urban Agenda. Habitat Int. 2018, 75, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. Formalizing the Informal: Understanding the Position of Informal Settlements and Slums in Sustainable Urbanization Policies and Strategies in Bandung, Indonesia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, R.; van Ballegooijen, J. The Routledge Handbook on Informal Urbanization, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, J.R.; Wang, H.; Tsai, T. Urban Informality in the Paris Climate Agreement: Content Analysis of the Nationally Determined Contributions of Highly Urbanized Developing Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda, 1st ed.; United Nations: Quito, Ecuador, 2017; pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wekesa, B.W.; Steyn, G.S.; Otieno, F.A.O. A review of physical and socio-economic characteristics and intervention approaches of informal settlements. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, F.A.M. The future of informal settlements: Lessons in the legalization of disputed urban land in Recife, Brazil. Geoforum 2001, 32, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J. Futuro, Cidades e Território. Finisterra 2016, 51, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullan, N. Temporary dwellings as informal suburban development in the global North and the case of Sydney 1945–1960. Plan. Perspect. 2019, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, J. Urban land policy and new land tenure paradigms: Legitimacy vs. legality in Brazilian cities. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabannes, Y.; Sevgi, O. Land disputes on the outskirts of Istanbul: A unique case of legalization amidst demolitions and forced evictions. Environ. Urban. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, Y.; Infante, J.M. Regularización y derecho a la vivienda: Un caso del área metropolitana de Monterrey. Front. Norte 2015, 27, 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, C.A. Direito à moradia e conciliação judicial de conflitos coletivos possessórios: A experiência de Porto Alegre. Rev. Direito Cid. 2017, 9, 2072–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Burriel, E.L. Las viviendas secundarias ilegales de la etapa del desarrollismo. Un ejemplo de Gilet (Valencia). Cuad. Geogr. 2018, 100, 23–58. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, T. Caves to castles: The development of second home practices in New Zealand. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2019, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeković, S.; Petovar, K.; Saman, B.M. The credibility of illegal and informal construction: Assessing legalization policies in Serbia. Cities 2020, 97, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacerauskas, T. Urban (Un)Sustainability: Cases of Vilnius’s Informal and Illegal Settings. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Biase, C.; Losco, S. Up-grading Illegal Building Settlements: An Urban-Planning Methodology. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2017, 37, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanasescu, A.; Chui, E.; Smart, A. Tops and bottoms: State tolerance of illegal housing in Hong Kong and Calgary. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santiago, E.; González, I. Condiciones de la edificación de vivienda aislada en suelo no urbanizable. Estudio de su regulación normativa. Cuad. Investig. Urbanística 2018, 120, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E. Consideraciones generales sobre las políticas públicas de regularización de asentamientos informales en América Latina. EURE 2008, 34, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.J. Urbanization and Counterurbanization, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1976; pp. 1–334. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, A. Ciudad y Naturaleza: Elementos para una genealogía de lo verde en la ciudad. Baetica 1992, 14, 115–146. [Google Scholar]

- Montosa, J.C. Población y urbanización en el área metropolitana de Málaga. Rev. Estud. Reg. 2012, 93, 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc, M.; Printsmann, A.; Palang, H.; Skowronek, E.; Woloszyn, W.; Konkoly, E. Comprehension of rapidly transforming landscapes of central and eastern Europe in the 20th century. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2004, 44, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, S. La metropolización del territorio en el cambio de siglo: Dispersión metropolitana, urbanización del medio rural y transformación de los espacios turísticos en la Europa mediterránea. Biblio 3w 2016, 21, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chiodelli, F. The dark side of urban informality in the Global North: Housing Illegality and Organized Crime in Northern Italy. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2019, 43, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curci, F. La residenzialità ricreativa ai margini dell’urbanistica italiana. Territorio 2014, 70, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, V.; Malheiros, J.; Campesino, A.J. La función residencial en la regulación del suelo no urbanizable de la península ibérica. Finisterra 2019, 54, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata, A. Guía de Escenarios Regionalizados de Cambio Climático sobre España a Partir de los Resultados del IPCC-AR4, 1st ed.; Agencia Estatal de Meteorología: Madrid, Spain, 2014; pp. 19–26.

- Loustau, D.; Bosc, A.; Colin, A.; Ogée, J.; Davi, H.; François, C.; Dufrêne, E.; Déqué, M.; Cloppet, E.; Arrouays, D.; et al. Modeling climate change effects on the potential production of French plains forests at the sub-regional level. Tree Physiol. 2005, 25, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Maroschek, M.; Netherer, S.; Kremer, A.; Barbati, A.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Seidl, R.; Delzon, S.; Corona, P.; Kolström, M.; et al. Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröter, D.; Cramer, W.; Leemans, R.; Colin, I.; Araújo, M.B.; Arnell, N.W.; Bondeau, A.; Bugmann, H.; Carter, T.R.; Gracia, C.A.; et al. Ecosystem Service Supply and Vulnerability to Global Change in Europe. Science 2005, 310, 1333–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E. Ecological footprints and sustainable urban form. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2004, 19, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, I.; Calatayud, D.; Dobaño, R. The compensation hypothesis in Barcelona measured through the ecological footprint of mobility and housing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 113, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, R.; Egidi, G.; Vinci, S.; Salvati, L. Desertification Risk and Rural Development in Southern Europe: Permanent Assessment and Implications for Sustainable Land Management and Mitigation Policies. Land 2019, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L. Neither Urban Nor Rural: Urban Growth, Economic Functions and the Use of Land in the Mediterranean Fringe. In Research in Rural Sociology and Development, 1st ed.; Marsden, T., Ed.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2016; Volume 23, pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; DeFries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K. Global Consequences of Land Use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, J.; Agredo, G.A. Pérdida de la cobertura vegetal y de oxígeno en la media montaña del trópico andino, caso cuenca urbana San Luis (Manizales). Luna Azul 2013, 37, 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, P.; Kenworthy, J. Sustainability and Cities; Overcoming Automobile Dependency, 1st ed.; Island Press: Covelo, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 1–442. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, D.M.; Carrega, P.; Ren, Y.; Caillouet, P.; Bouillon, C.; Robert, S. How wildfire risk is related to urban planning and Fire Weather Index in SE France (1990–2013). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, F.; Pérez-Morales, A.; Illán-Fernández, E.J. Are local administrations really in charge of flood risk management governance? The Spanish Mediterranean coastline and its institutional vulnerability issues. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Felice, P. Ranking of Illegal Buildings Close to Rivers: A Proposal, Its Implementation and Preliminary Validation. Isprs Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Zhang, A.; Wang, H.; Liu, J. Delineating early warning zones in rapidly growing metropolitan areas by integrating a multiscale urban growth model with biogeography-based optimization. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P. Designing urban rules from emergent patterns: Co-evolving paths of informal and formal urban systems—The case of Portugal. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 158, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, J.; Chatiza, K. Frontiers of Urban Control: Lawlessness on the City Edge and Forms of Clientalist Statecraft in Zimbabwe. Antipode 2019, 51, 1554–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, J.C. La regularización de parcelaciones ilegales en Aragón. Rev. Gestión Pública Priv. 1996, 1, 319–344. [Google Scholar]

- Conejo, E.; Goycoolea, R. Participación pública en la nueva ordenación del territorio rural madrileño. Ley 5/2012 de Viviendas Rurales Sostenibles. Encrucijadas 2013, 6, 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.J. Los esfuerzos del legislador andaluz por regularizar edificaciones en suelo no urbanizable: Un último episodio, la ley 6/2016, de 1 de agosto. Rev. Andal. Adm. Pública 2017, 97, 141–190. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, V.; Delgado, C.; Campesino, A.J. Desregulación urbanística del suelo rústico en España. Cantabria y Extremadura como casos de estudio. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2017, 67, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, A. Private or Public: Debating the Meaning of Tenure Legalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2002, 26, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relli, M. Desencuentros entre política urbana y política de regularización del hábitat popular en La Plata, Argentina. Geogr. Univ. Complut. 2019, 39, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsenkova, S. Urban planning and informal cities in Southeast Europe. J. Arch. Plan. Res. 2012, 29, 292–305. [Google Scholar]

- Pojani, D. From Squatter Settlement to Suburb: The Transformation of Bathore, Albania. Hous. Stud. 2013, 28, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Virgilio, M.M.; Guevara, T.A.; Arqueros, M.S. Políticas de regularización en barrios populares de origen informal en Argentina, Brasil y México. Urbano 2014, 29, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, P.; Quastel, N. Subterranean Commodification: Informal Housing and the Legalization of Basement Suites in Vancouver from 1928 to 2009. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 1155–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, P.; Wigle, J. (Re)constructing Informality and “Doing Regularization” in the Conservation Zone of Mexico City. Plan. Theory Pract. 2017, 18, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistema de Información Territorial de Extremadura. Available online: http://sitex.gobex.es (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Sun, L.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, L. Rural Building Detection in High-Resolution Imagery Based on a Two-Stage CNN Model. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 1998–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefiyan, F.; Ebadi, H.; Sedaghat, A. Integrated Local Features to Detect Building Locations in High-Resolution Satellite Imagery. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2019, 47, 1375–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, V.; Campesino, A.J.; Alvarado, V.; Hidalgo, R.; Borsdorf, A. Flood risk and imprudence of planning in Extremadura, Spain. Land Use Policy 2019, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremambiente. Available online: http://extremambiente.juntaex.es/index.php (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Hernández, P. Consideración teórica sobre la prensa como fuente historiográfica. Hist. Común. Soc. 2017, 22, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Durán, A.M.M. Población y Territorio en Extremadura. Siglos XVIII-XX. Ph.D. Thesis, National University of Distance Education, Madrid, Spain, 14 Feburary 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burriel, E.L. La “década prodigiosa” del urbanismo español (1997–2006). Scr. Nova: Rev. Electrón. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2008, 12, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, V. Urbanizaciones Ilegales en Extremadura. La Proliferación de Viviendas en el Suelo no Urbanizable durante el Periodo Democrático. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Extremadura, Cáceres, Spain, 14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- A.S.O. Díaz dice que se actúa en Santa Bárbara igual que otras corporaciones. Diario HOY, 12 April 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos, C. Santa Bárbara: Tres décadas de barra libre. Diario HOY. 12 March 2017. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/plasencia/201703/12/santa-barbara-tres-decadas-20170312003209-v.html (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Editorial Staff. Durán pregunta “qué pintan” las casas ilegales en la sierra. El Periódico Extremadura. 11 December 2005. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/duran-pregunta-que-pintan-casas-ilegales-sierra_209915.html (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- R.R. La falta de personal permite que 49 casas ilegales sigan en la sierra. El Periódico Extremadura. 14 January 2009. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/falta-personal-permite-49-casas-ilegales-sigan-sierra_420594.html (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Dueñas, M. La policía local denunció el año pasado más de 160 construcciones ilegales. El Periódico Extremadura. 1 March 2008. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/policia-local-denuncio-ano-pasado-mas-160-construcciones-ilegales_358863.html (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- A.S.O. Santa Bárbara pide un paso peatonal elevado en el cruce ‘Valdeolivos’. Diario HOY. 8 November 2008. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/20081108/plasencia/santa-barbara-pide-paso-20081108.html (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Editorial Staff. Critican que el PGOU permita construir en Santa Bárbara. El Periódico Extremadura. 28 December 2009. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/critican-pgou-permita-construir-santa-barbara_484108.html (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- A.S.O. El Colegio de Arquitectos cuestiona la ordenación industrial y de Sta. Bárbara. Diario HOY, 25 April 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano, A.L. Pizarro se alía con los ecologistas frente al parque eólico de la sierra. Diario HOY. 25 August 2012. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/v/20120825/plasencia/pizarro-alia-ecologistas-frente-20120825.html (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Rodríguez, R. La plataforma antimolinos de Plasencia ve un peligro su cercanía a las viviendas. El Periódico Extremadura. 27 December 2013. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/plataforma-antimolinos-plasencia-ve-peligro-cercania-viviendas_777353.html (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- A.B.H. La Policía denuncia 19 edificaciones clandestinas en Santa Bárbara. Diario HOY, 30 April 2003. [Google Scholar]

- A.S.O. Urbanismo detectó en 2008 la construcción de 8 casas clandestinas en la Sierra. Diario HOY. 14 January 2009. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/20090114/plasencia/urbanismo-detecto-2008-construccion-20090114.html (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Rodríguez, R. Urbanismo ha llevado 20 casos de casas ilegales al juzgado. El Periódico Extremadura. 24 December 2012. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/urbanismo-ha-llevado-20-casos-casas-ilegales-juzgado_701601.html (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Hernández, A.B. Urbanismo denuncia ante la Fiscalía una quincena de construcciones ilegales. Diario HOY. 12 May 2012. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/v/20120512/plasencia/urbanismo-denuncia-ante-fiscalia-20120512.html (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- EFE. La Junta apoya la regularización de viviendas en la sierra de Santa Bárbara. Diario HOY. 7 May 2009. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/20090507/local/plasencia/junta-apoya-regularizacion-viviendas-200905071824.html (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Rodríguez, R. Los costes de regularizar casas de la sierra los pagará el dueño. El Periódico Extremadura. 16 June 2012. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/costes-regularizar-casas-sierra-pagara-dueno_660471.html (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Hernández, A.B. Ninguna de las más de 50 resoluciones de derribo se ha ejecutado en Santa Bárbara. Diario HOY. 24 April 2009. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/20090424/plasencia/ninguna-resoluciones-derribo-ejecutado-20090424.html (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Hernández, A.B. Las casas ilegales proliferan en la ciudad. Diario HOY. 19 April 2012. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/v/20120419/plasencia/casas-ilegales-proliferan-ciudad-20120419.html (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Agencias Mérida. Domínguez, expedientada, declara hoy con “tranquilidad”. El Periódico Extremadura. 19 July 2017. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/dominguez-expedientada-declara-hoy-tranquilidad_1029366.html (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- EFE. El alcalde afirma que Domínguez “intenta echar la mierda a todo el mundo” en el ‘caso Plasencia’. El Periódico Extremadura. 30 November 2017. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/alcalde-afirma-dominguez-intenta-echar-mierda-todo-mundo-caso-plasencia_1056446.html (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Rodríguez, R. Victoria Domínguez, Blanco y Díaz impugnan el recurso de la fiscalía. El Periódico Extremadura. 1 June 2018. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/victoria-dominguez-blanco-diaz-impugnan-recurso-fiscalia_1093080.html (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Rodríguez, R. El ayuntamiento da curso a más de 120 expedientes urbanísticos. El Periódico Extremadura. 24 September 2018. Available online: http://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/ayuntamiento-da-curso-mas-120-expedientes-urbanisticos_1115215.html (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Hernández, A.B. Tiran la primera casa de la sierra de Santa Bárbara en Plasencia. Diario HOY. 17 September 2019. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/plasencia/tiran-primera-casa-20190917211238-nt.html (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Hernández, A.B. Santa Bárbara reclama un documento que muestre el inicio de la regularización Presenta. Diario HOY. 4 December 2019. Available online: https://www.hoy.es/plasencia/santa-barbara-reclama-20191204001959-ntvo.html (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Rodríguez, R. Pizarro: “Santa Bárbara lleva 40 años y no se resuelve en meses”. El Periódico Extremadura. 20 January 2020. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/pizarro-santa-barbara-lleva-40-anos-no-resuelve-meses_1213312.html (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Rodríguez, R. El ayuntamiento iniciará el trámite de regularizaciones en la sierra”. El Periódico Extremadura. 13 February 2020. Available online: https://www.elperiodicoextremadura.com/noticias/plasencia/ayuntamiento-iniciara-tramite-regularizaciones-sierra_1218013.html (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Mukhija, V. An analytical framework for urban upgrading:property rights, property values and physical attributes. Habitat Int. 2002, 26, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urazán, C.F.; Magrinyà, F. El rol de los servicios urbanos en la legalización predial y la generación de calidad urbana y valor del suelo. Aplicación al caso de Cúcuta (Colombia). Hábitat Soc. 2015, 8, 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, M.P.; Ramalhete, I.; Amado, A.R.; Freitas, J.C. Regeneration of informal areas: An integrated approach. Cities 2016, 58, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwaleba, M.J.; Chigbu, U.E. Participation in property formation: Insights from land-use planning in an informal urban settlement in Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilon, M.; Eizenberg, E. Critical pedagogy for the new planner: Mastering an inclusive perception of ‘The Other’. Cities 2020, 97, 102500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, E.; Zambrano-Verratti, J.; Kleinhans, R. Web-based participatory mapping in informal settlements: The slums of Caracas, Venezuela. Habitat Int. 2019, 94, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R. Out of Place? Global Citizens in Local Spaces: A Study of the Informal Settlements in the Korle Lagoon Environs in Accra, Ghana. Urban Forum 2006, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuskar, C. Informal urbanisation and clientelism: Measuring the global relationship. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 0042098019878334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, A.E. Cities and Politics in the Developing World. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2018, 21, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez Barrado, V. Evolution and Management of Illegal Settlements in Mid-Sized Towns. The Case of Sierra de Santa Bárbara (Plasencia, Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083438

Jiménez Barrado V. Evolution and Management of Illegal Settlements in Mid-Sized Towns. The Case of Sierra de Santa Bárbara (Plasencia, Spain). Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083438

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez Barrado, Víctor. 2020. "Evolution and Management of Illegal Settlements in Mid-Sized Towns. The Case of Sierra de Santa Bárbara (Plasencia, Spain)" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083438

APA StyleJiménez Barrado, V. (2020). Evolution and Management of Illegal Settlements in Mid-Sized Towns. The Case of Sierra de Santa Bárbara (Plasencia, Spain). Sustainability, 12(8), 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083438