Mechanism Between Physical Activity and Academic Anxiety: Evidence from Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

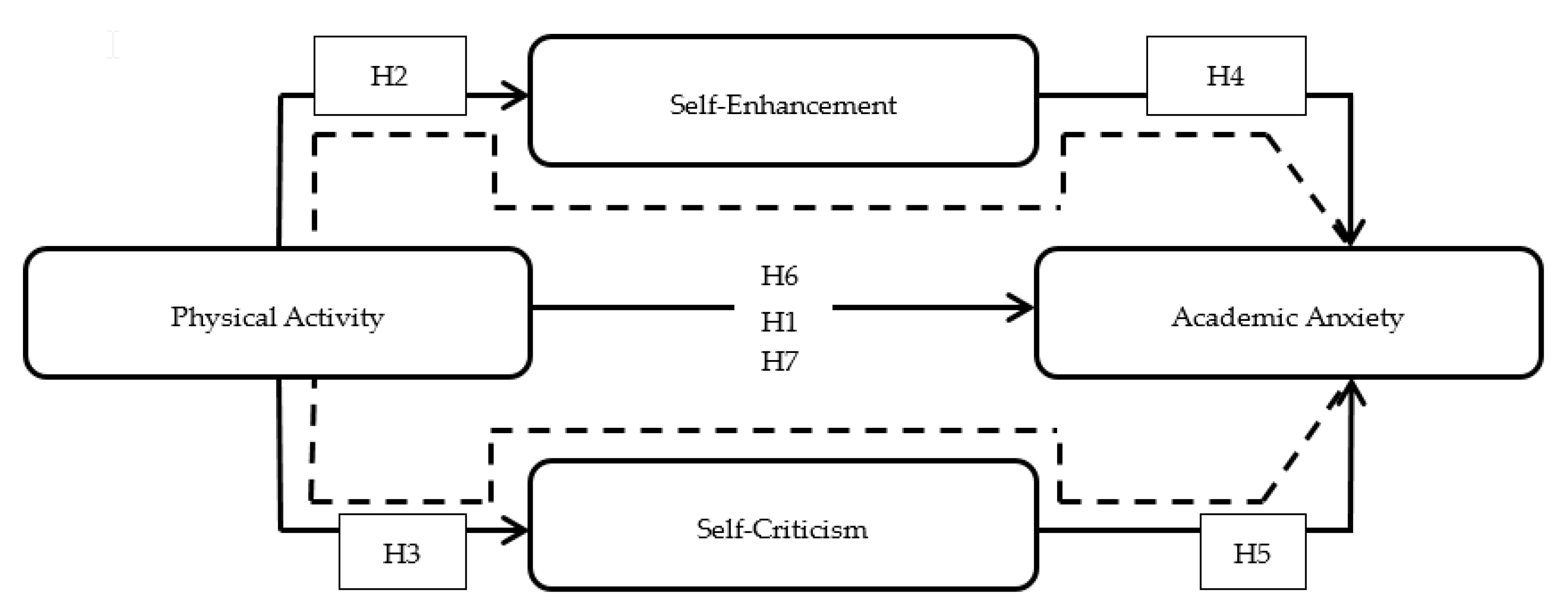

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.1.1. Physical Activity and Academic Anxiety

1.1.2. Self-Enhancement as a Mediator

1.1.3. Self-Criticism as a Mediator

1.1.4. Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Measurement of Variables

2.3.1. Physical Activity

2.3.2. Self-Enhancement

2.3.3. Self-Criticism

2.3.4. Academic Anxiety

2.3.5. Control Variables

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses

3.2. Common Method Bias

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

3.4. Correlation

3.5. Model Fit Statistics

3.6. Structural Models

3.6.1. Direct Effects

3.6.2. Mediation (Indirect Effects)

3.7. Hierarchical Regression Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asigbee, F.M.; Whitney, S.D.; Peterson, C.E. The link between nutrition and physical activity in increasing academic achievement. J. Sch. Health 2018, 88, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayani, S.; Kiyani, T.; Wang, J.; Zagalaz Sánchez, M.; Kayani, S.; Qurban, H. Physical Activity and Academic Performance: The Mediating Effect of Self-Esteem and Depression. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Niu, L.; Zhang, D.; Ip, P.; Ho, F.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhu, Q.; Jiang, F. Social-Emotional Functioning Explains the Effects of Physical Activity on Academic Performance among Chinese Primary School Students: A Mediation Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2019, 208, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruijn, A.; Hartman, E.; Kostons, D.; Visscher, C.; Bosker, R. Exploring the relations among physical fitness, executive functioning, and low academic achievement. J. Exper. Child Psychol. 2018, 167, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, S.; MacIntosh, L.; O’Neill, C.; D’Silva, C.; Shearer, H.; Smith, K.; Cote, P. The association of physical activity with depression and stress among post-secondary school students: A systematic review. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2018, 14, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, K.A.; Blumenthal, J.A. Exercise training and depression in older adults. Neurobiol. Aging 2005, 26, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Cale, L.; Duncombe, R.; Musson, H. Young people’s knowledge and understanding of health, fitness and physical activity: Issues, divides and dilemmas. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. The association between physical fitness and physical activity among Chinese college students. J. Am. Health 2019, 67, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loprinzi, P.D.; Cardinal, B.J.; Cardinal, M.K.; Corbin, C.B. Physical education and sport: Does participation relate to physical activity patterns, observed fitness, and personal attitudes and beliefs? Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, W. A systematic review of the relationship between physical activity and happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1305–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanzada, F.J.; Soomro, N.; Khan, S.Z. Association of physical exercise on anxiety and depression amongst adults. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2015, 25, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aşçı, F.H. The effects of physical fitness training on trait anxiety and physical self-concept of female university students. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine–evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multon, K.D.; Heppner, M.J.; Gysbers, N.C.; Zook, C.; Ellis-Kalton, C.A. Client psychological distress: An important factor in career counseling. Career Dev. Q. 2001, 49, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larun, L.; Nordheim, L.V.; Ekeland, E.; Hagen, K.B.; Heian, F. Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 3, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stathopoulou, G.; Powers, M.B.; Berry, A.C.; Smits, J.A.; Otto, M.W. Exercise interventions for mental health: A quantitative and qualitative review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Prac. 2006, 13, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vliet, P.; Knapen, J.; Onghena, P.; Fox, K.R.; David, A.; Morres, I.; Van Coppenolle, H.; Pieters, G. Relationships between self-perceptions and negative affect in adult Flemish psychiatric in-patients suffering from mood disorders. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2002, 3, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, L.L. Exercise and clinical depression: Examining two psychological mechanisms. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2005, 6, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Kendrick, T.; Yardley, L. Change in self-esteem, self-efficacy and the mood dimensions of depression as potential mediators of the physical activity and depression relationship: Exploring the temporal relation of change. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2009, 2, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhie, M.L.; Rawana, J.S. Unravelling the relation between physical activity, self-esteem and depressive symptoms among early and late adolescents: A mediation analysis. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2012, 5, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, L.S.; Prapavessis, H.; Osuch, E.A.; De Pace, J.A.; Murphy, B.A.; Podolinsky, N.J. An examination of potential mechanisms for exercise as a treatment for depression: A pilot study. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2008, 1, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, G.; Carless, D. Physical activity in the process of psychiatric rehabilitation: Theoretical and methodological issues. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2006, 29, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, Y.; Sultan, Z.; Moeinaddini, M.; Ahmed Jokhio, G. Measuring the differences of neighbourhood environment and physical activity in gated and non-gated neighbourhoods in Karachi, Pakistan. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arat, G.; Wong, P.W.-C. The relationship between physical activity and mental health among adolescents in six middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study. Child Youth Serv. 2017, 38, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.A. Interaction of physical activity, mental health, health locus of control and quality of life: A study on University students in Pakistan. Master’s Thesis, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland, 20 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, J.C.; Worsley, J.; Corcoran, R.; Harrison Woods, P.; Bentall, R.P. Academic and non-academic predictors of student psychological distress: The role of social identity and loneliness. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, Í.J.; Pereira, R.; Freire, I.V.; de Oliveira, B.G.; Casotti, C.A.; Boery, E.N. Stress and quality of life among university students: A systematic literature review. Health Prof. Educ. 2018, 4, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahranavard, S.; Esmaeili, A.; Dastjerdi, R.; Salehiniya, H. The effectiveness of stress-management-based cognitive-behavioral treatments on anxiety sensitivity, positive and negative affect and hope. BioMedicine 2018, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; Concina, E. The role of coping strategy and experience in predicting music performance anxiety. Music. Sci. 2014, 18, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babyak, M.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Herman, S.; Khatri, P.; Doraiswamy, M.; Moore, K.; Craighead, W.E.; Baldewicz, T.T.; Krishnan, K.R. Exercise treatment for major depression: Maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom. Med. 2000, 62, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibold, J.S.; Berg, K.M. Mood enhancement persists for up to 12 hours following aerobic exercise: A pilot study. Percept. Mot. Skills 2010, 111, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qurban, H.; Wang, J.; Siddique, H.; Morris, T.; Qiao, Z. The mediating role of parental support: The relation between sports participation, self-esteem, and motivation for sports among chinese students. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 38, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.C.H.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.; Fontes-Comber, A. Psychological and social outcomes of sport participation for older adults: A systematic review. Ageing Soc. 2019, 0, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, R.B.; Campos, M.H.; Santos, D.D.A.T.; Xavier, I.C.M.; Vancini, R.L.; Andrade, M.S.; de Lira, C.A.B. Improving Academic Performance of Sport and Exercise Science Undergraduate Students in Gross Anatomy Using a Near-Peer Teaching Program. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2019, 12, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomitz, V.R.; Slining, M.M.; McGowan, R.J.; Mitchell, S.E.; Dawson, G.F.; Hacker, K.A. Is there a relationship between physical fitness and academic achievement? Positive results from public school children in the northeastern United States. J. Sch. Health 2009, 79, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.E.; Brown, J.D. Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skayannis, P.; Goudas, M.; Rodakinias, P. Sustainable mobility and physical activity: A meaningful marriage. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 24, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, A.; Zulaika, L. Relationships between physical education classes and the enhancement of fifth grade pupils’ self-concept. Percept. Mot. Skills 2000, 91, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I. Social factors associated with centenarian rate (CR) in 32 OECD countries. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2013, 13, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Fellendorf, F.; Kainzbauer, N.; Platzer, M.; Dalkner, N.; Bengesser, S.; Birner, A.; Queissner, R.; Rauch, P.; Hamm, C.; Pilz, R. Gender differences in the association between physical activity and cognitive function in individuals with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 221, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timo, J.; Sami, Y.-P.; Anthony, W.; Jarmo, L. Perceived physical competence towards physical activity, and motivation and enjoyment in physical education as longitudinal predictors of adolescents’ self-reported physical activity. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 750–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, C.J.; Kolev, D.; Hall, P.A. An exploration of exercise-induced cognitive enhancement and transfer effects to dietary self-control. Brain Cogn. 2016, 110, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullrich-French, S.; Cole, A.N.; Montgomery, A.K. Evaluation development for a physical activity positive youth development program for girls. Eval. Program Plan. 2016, 55, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyasi, R.M. Social support, physical activity and psychological distress among community-dwelling older Ghanaians. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 81, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, T.A.; Zuroff, D.C. Interpersonal consequences of overt self-criticism: A comparison with neutral and self-enhancing presentations of self. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindwall, M.; Hassmén, P. The role of exercise and gender for physical self-perceptions and importance ratings in Swedish university students. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2004, 14, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapen, J.; Van de Vliet, P.; Van Coppenolle, H.; David, A.; Peuskens, J.; Pieters, G.; Knapen, K. Comparison of changes in physical self-concept, global self-esteem, depression and anxiety following two different psychomotor therapy programs in nonpsychotic psychiatric inpatients. Psychother. Psychosom. 2005, 74, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, S.J.; Nigg, C.R. Theories of exercise behavior. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2000, 31, 290–304. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, M.; McEachan, R.; Taylor, N.; O’Hara, J.; Lawton, R. Role of affective attitudes and anticipated affective reactions in predicting health behaviors. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.J.; Edwards, S.D.; Basson, C.J. Psychological well-being and physical self-esteem in sport and exercise. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2004, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, R.S.W.; Gould, D. Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology: Study Guide; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, B.L.; Whealin, J.M.; Harpaz-Rotem, I.; Duman, R.S.; Krystal, J.H.; Southwick, S.M.; Pietrzak, R.H. BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and posttraumatic stress symptoms in US military veterans: Protective effect of physical exercise. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 100, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberger, C.; Spörrle, M.; Welpe, I.M. Not fearless, but self-enhanced: The effects of anxiety on the willingness to use autonomous cars depend on individual levels of self-enhancement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 116, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, L.L.; Landers, D.M. The effect of exercise on clinical depression and depression resulting from mental illness: A meta-analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1998, 20, 33–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatt, S.J. Levels of object representation in anaclitic and introjective depression. Psychoanal. Study Child 1974, 29, 107–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halamová, J.; Kanovský, M. Emotion-focused training for emotion coaching–an intervention to reduce self-criticism. Hum. Aff. 2019, 29, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.-H.; Ramos, J.; Dey, A.K. Understanding physiological responses to stressors during physical activity. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 5–8 September 2012; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; Venigalla, S.K.; Probst, M. Adopting and maintaining physical activity behaviours in people with severe mental illness: The importance of autonomous motivation. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.; Wang, C.J.; Kavussanu, M.; Spray, C. Correlates of achievement goal orientations in physical activity: A systematic review of research. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2003, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, E.; Özcan, D. A study about self and criticism and the physical acts involved in their education. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 136, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Van Damme, T.; Probst, M.; Vandael, H.; Hallgren, M.; Mutamba, B.B.; Nabanoba, J.; Basangwa, D.; Mugisha, J. Motives for physical activity in the adoption and maintenance of physical activity in men with alcohol use disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, D.M.; Zuroff, D.C.; Blankstein, K.R. Specific perfectionism components versus self-criticism in predicting maladjustment. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.A.F. Exercise comes of age: Rationale and recommendations for a geriatric exercise prescription. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2002, 57, M262–M282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Cable, N.; Faulkner, G.; Hillsdon, M.; Narici, M.; Van Der Bij, A. Physical activity and older adults: A review of health benefits and the effectiveness of interventions. J. Sports Sci. 2004, 22, 703–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamil, F.; Khalid, R. Factors contributing to depression during peri menopause: Findings of a Pakistani sample. Sex Roles 2016, 75, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, J.; Faulkner, G.; Veldhuizen, S.; Wade, T.J. Changes over time in physical activity and psychological distress among older adults. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, M.; Zaman Khan, S.; Ali Shah, S.Z. A Study of the Relationship Between Innovation and Performance Among NPOs in Pakistan. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2020, 46, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranis, L.; Meyer, C. Perfectionism and compulsive exercise among female exercisers: High personal standards or self-criticism? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-H. Preliminary reliability of the five item physical activity questionnaire. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 3393–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, E.G.; Gramzow, R.H.; Sedikides, C. Individual differences in self-enhancement and self-protection strategies: An integrative analysis. J. Personal. 2010, 78, 781–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepper, E.G.; Sedikides, C.; Cai, H. Self-enhancement and self-protection strategies in China: Cultural expressions of a fundamental human motive. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.; Zuroff, D.C. The Levels of Self-Criticism Scale: Comparative self-criticism and internalized self-criticism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.R.; Naqvi, I. Self-criticism and fear of negative evaluation among university students with and without obesity. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2016, 31, 509–530. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.; Jacobs, G. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Marteau, T.M.; Bekker, H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State—Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 31, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 20.0; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2011.

- Hair, J.F.; Black, B.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle Creek, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Study Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update; Allyn & Bacon, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts. In Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Landers, D.M.; Arent, S.M. Physical activity and mental health. In Handbook of Sport Psychology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 2, pp. 740–765. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, M.; Niazi, S.; Ghayas, S. Relationship between Self-Esteem and Social Anxiety: Role of Social Connectedness as a Mediator. Pak. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 15, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Z.R.; Bano, N.; Ahmad, R.; Khanam, S. Social anxiety in adolescents: Does self-esteem matter. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2013, 2, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Yousafzai, A.W.; Siddiqui, M.N. Association of lower self esteem with depression: A case control study. J. Postgrad. Med. Inst. 2011, 21, 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, S. The Relation between Self-Esteem, Parenting Style and Social Anxiety in Girls. J. Educ. Prac. 2015, 6, 140–142. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.; Fatima, G.; Hussain Ch, A. Test Anxiety and Self-Concept of University Students Enrolled in B Ed Honors Degree Program Funded by USAID. Bull. Educ. Res. 2016, 38, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, G. Erosion: The Psychopathology of Self-Criticism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, M.; Paiva, M.J. Text anxiety in adolescents: The role of self-criticism and acceptance and mindfulness skills. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Kim, M.-S.; Akutsu, S. The effects of self-construals, self-criticism, and self-compassion on depressive symptoms. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014, 68, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables and Items | EFA | CFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | C.R. | AVE | √AVE | MSV | ||

| Physical Activity | α = 0.912 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.82 | 0.12 | |

| 1. What type of physical activity are you doing? | 0.831 | 0.87 *** | ||||

| 2. During a week, how often do you participate in the activity in your free time? | 0.710 | 0.75 *** | ||||

| 3. How intensely do you participate in the activity? | 0.861 | 0.82 *** | ||||

| 4. How long do you do the activity in your free time? | 0.740 | 0.77 *** | ||||

| 5. How monthly have you been performing the activity? | 0.821 | 0.88 *** | ||||

| Self-enhancement | α = 0.954 | 0.95 | 0.50 | 0.71 | 0.12 | |

| 1. When you achieve success or really good grades, thinking it was due to your ability. | 0.831 | 0.71 *** | ||||

| 2. Thinking of yourself as generally possessing positive personality traits or abilities to a greater extent than most people | 0.810 | 0.74 *** | ||||

| 3. Remembering hardships that you had to overcome to be really successful. | 0.710 | 0.72 *** | ||||

| 4. When you do poorly at something or get bad grades, thinking it was due to bad luck. | 0.700 | 0.76 *** | ||||

| 5. When you achieve success or really good grades, thinking it says a lot about you as a person. | 0.820 | 0.71 *** | ||||

| 6. Believing that you are changing, growing, and improving as a person more than other people are. | 0.811 | 0.75 *** | ||||

| 7. Thinking about how you have grown and improved as a person over time; how much more good/honest/skilled you are now than you used to be. | 0.830 | 0.68 *** | ||||

| 8. When you do poorly at something or get bad grades, thinking that the situation or test was uninformative or inaccurate. | 0.726 | 0.70 *** | ||||

| 9. When you achieve success or really good grades, playing up the importance of that ability or area of life. | 0.813 | 0.71 *** | ||||

| 10. Believing you are more likely than most people to be happy and successful in the | 0.728 | 0.71 *** | ||||

| 11. In times of stress, reminding yourself of your values and what matters to you | 0.750 | 0.69 *** | ||||

| 12. When you do poorly at something or get bad grades, thinking hard about the situation and feedback until you find something wrong with it and can discount it | 0.811 | 0.66 *** | ||||

| 13. Spending time with people who think highly of you, say good things about you, and make you feel good about yourself | 0.751 | 0.71 *** | ||||

| 14. When someone says something ambiguous about you, interpreting it as a positive comment or compliment. | 0.714 | 0.67 *** | ||||

| 15. In times of stress, thinking about your positive close relationships and loved ones. | 0.841 | 0.68 *** | ||||

| 16. Revising very little for a test, or going out the night before an exam or appraisal at work, so that if you do well, it would mean you must have very high ability | 0.840 | 0.67 *** | ||||

| 17. Asking for feedback when you expect a positive answer | 0.813 | 0.75 *** | ||||

| 18. Generally getting over the experience of negative feedback quickly, so a few hours/days/weeks after a negative event you no longer feel bad. | 0.821 | 0.70 *** | ||||

| 19. Thinking about how things could have been much worse than they are. | 0.816 | 0.72 *** | ||||

| 20. Revising very little for a test, or going out the night before an exam or appraisal at work, so that if you do poorly, it would not mean you are incompetent | 0.811 | 0.70 *** | ||||

| Self-criticism | α = 0.967 | 0.97 | 0.58 | 0.76 | 0.06 | |

| 1. I am very irritable when I have failed. | 0.851 | 0.86 *** | ||||

| 2. I have a nagging sense of inferiority. | 0.820 | 0.81 *** | ||||

| 3. I am very frustrated with myself when I don’t meet the standards I have for myself. | 0.852 | 0.87 *** | ||||

| 4. I am usually uncomfortable in social situations where I don’t know what to expect. | 0.811 | 0.63 *** | ||||

| 5. I often get very angry with myself when I fail. | 0.710 | 0.88 *** | ||||

| 6. I don’t spend much time worrying about what other people will think of me. | 0.719 | 0.76 *** | ||||

| 7. I get very upset when I fail. | 0.811 | 0.79 *** | ||||

| 8. If you are open to other people about your weaknesses, they are likely to still respect you. | 0.705 | 0.76 *** | ||||

| 9. Failure is a very painful experience for me. | 0.813 | 0.66 *** | ||||

| 1. I often worry that other people will find out what I’m really like and be upset with me. | 0.811 | 0.67 *** | ||||

| 11. I don’t often worry about the possibility of failure. | 0.821 | 0.77 *** | ||||

| 12. I am confident that most of the people I care about will accept me for who I am. | 0.716 | 0.73*** | ||||

| 13. When I don’t succeed, I find myself wondering how worthwhile I am. | 0.855 | 0.77 *** | ||||

| 14. If you give people the benefit of the doubt, they are likely to take advantage of you. | 0.813 | 0.89 *** | ||||

| 15. I feel like a failure when I don’t do as well as I would like. | 0.811 | 0.68 *** | ||||

| 16. I am usually comfortable with people asking me about myself. | 0.815 | 0.65 *** | ||||

| 17. If I fail in one area, it reflects poorly on me as a person. | 0.823 | 0.83 *** | ||||

| 18. I fear that if people get to know me too well, they will not respect me. | 0.811 | 0.71 *** | ||||

| 19. I frequently compare myself with my goals and ideals. | 0.750 | 0.74 *** | ||||

| 20. I seldom feel ashamed of myself. | 0.899 | 0.88 *** | ||||

| 21. Being open and honest is usually the best way to keep others’ respect. | 0.781 | 0.63 *** | ||||

| 22. There are times that it is necessary to be somewhat dishonest to get what you want. | 0.716 | 0.65 *** | ||||

| Academic Anxiety | α = 0.864 | 0.86 | 0.50 | 0.71 | 0.09 | |

| 1. I feel calm | 0.719 | 0.73 *** | ||||

| 2. I am tense | 0.719 | 0.77 *** | ||||

| 3. I feel upset | 0.831 | 0.69 *** | ||||

| 4. I am relaxed | 0.801 | 0.71 *** | ||||

| 5. I am content | 0.716 | 0.66 *** | ||||

| 6. I am worried | 0.730 | 0.69 *** | ||||

| Factors | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | 3.62 | 0.68 | −0.91 | 1.66 |

| Self-Enhancement | 3.72 | 0.39 | −0.15 | 0.81 |

| Self-Criticism | 3.24 | 0.52 | −0.48 | −0.63 |

| Academic Anxiety | 2.78 | 0.49 | 0.78 | 1.36 |

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | |||||

| Education | −0.099 * | 1 | ||||

| Physical activity | −0.009 | −0.051 | 1 | |||

| Self-Enhancement | 0.079 | −0.015 | 0.347 ** | 1 | ||

| Self-Criticism | −0.053 | 0.011 | −0.115 * | −0.092 | 1 | |

| Academic Anxiety | 0.078 | 0.020 | −0.281 ** | −0.310 ** | 0.248 ** | 1 |

| Study Variables and Models | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | 3.77 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.082 | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| Self-enhancement | 2.85 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.067 | 0.352 | 0.000 |

| Self-criticism | 4.85 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.0812 | 0.041 | 0.000 |

| Academic anxiety | 2.74 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.042 | 0.074 | 0.000 |

| Measurement model | 2.31 | 0.911 | 0.901 | 0.056 | 0.046 | 0.000 |

| Structural model | 1.602 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.075 | 0.079 | 0.000 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p-Value | R2 | R2∆ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error | Beta | ||||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 2.608 | 0.075 | 34.747 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.016 | |

| Education | 0.034 | 0.032 | 0.054 | 1.069 | 0.286 | |||

| Age | 0.062 | 0.030 | 0.102 | 2.038 | 0.042 | |||

| 2 | (Constant) | 3.351 | 0.146 | 22.915 | 0.000 | 0.091 | 0.075 | |

| Education | 0.036 | 0.031 | 0.056 | 1.168 | 0.244 | |||

| Age | 0.049 | 0.029 | 0.081 | 1.665 | 0.097 | |||

| Physical_Activity | −0.199 | 0.034 | −0.275 | −5.841 | 0.000 | |||

| 3 | (Constant) | 3.485 | 0.278 | 12.520 | 0.000 | 0.191 | 0.101 | |

| Education | 0.054 | 0.029 | 0.085 | 1.857 | 0.064 | |||

| Age | 0.055 | 0.028 | 0.091 | 1.985 | 0.048 | |||

| Physical_Activity | −0.120 | 0.035 | −0.165 | −3.473 | 0.001 | |||

| Self_Enhancement | −0.304 | 0.060 | −0.240 | −5.054 | 0.000 | |||

| Self_Criticism | 0.206 | 0.043 | 0.215 | 4.808 | 0.000 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kayani, S.; Wang, J.; Biasutti, M.; Zagalaz Sánchez, M.L.; Kiyani, T.; Kayani, S. Mechanism Between Physical Activity and Academic Anxiety: Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093595

Kayani S, Wang J, Biasutti M, Zagalaz Sánchez ML, Kiyani T, Kayani S. Mechanism Between Physical Activity and Academic Anxiety: Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability. 2020; 12(9):3595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093595

Chicago/Turabian StyleKayani, Sumaira, Jin Wang, Michele Biasutti, María Luisa Zagalaz Sánchez, Tayyaba Kiyani, and Saima Kayani. 2020. "Mechanism Between Physical Activity and Academic Anxiety: Evidence from Pakistan" Sustainability 12, no. 9: 3595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093595

APA StyleKayani, S., Wang, J., Biasutti, M., Zagalaz Sánchez, M. L., Kiyani, T., & Kayani, S. (2020). Mechanism Between Physical Activity and Academic Anxiety: Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability, 12(9), 3595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093595