Environmental and Economic Sustainability of Table Grape Production in Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. LCA Analysis

2.1.1. Goal and Scope Definition

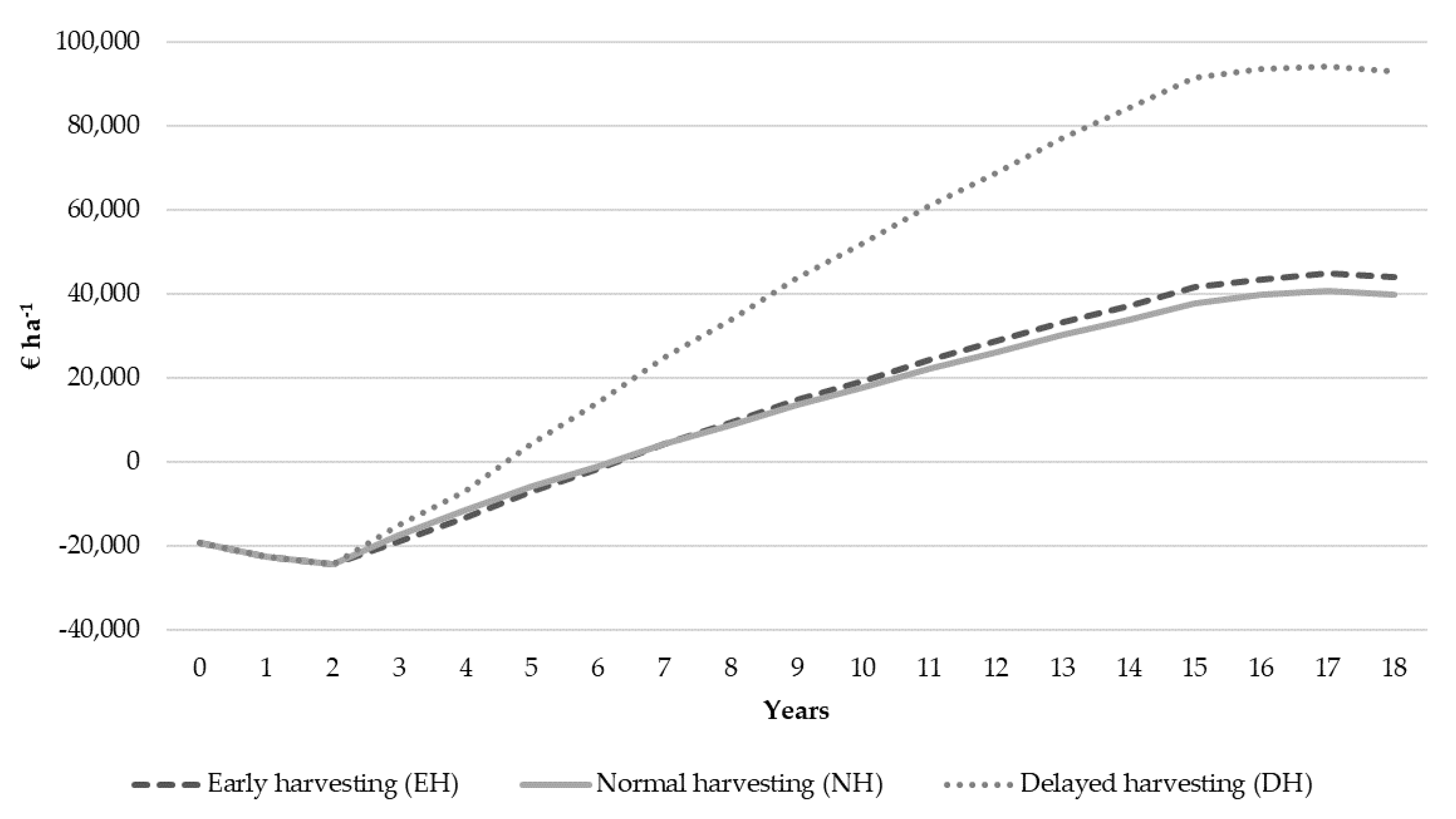

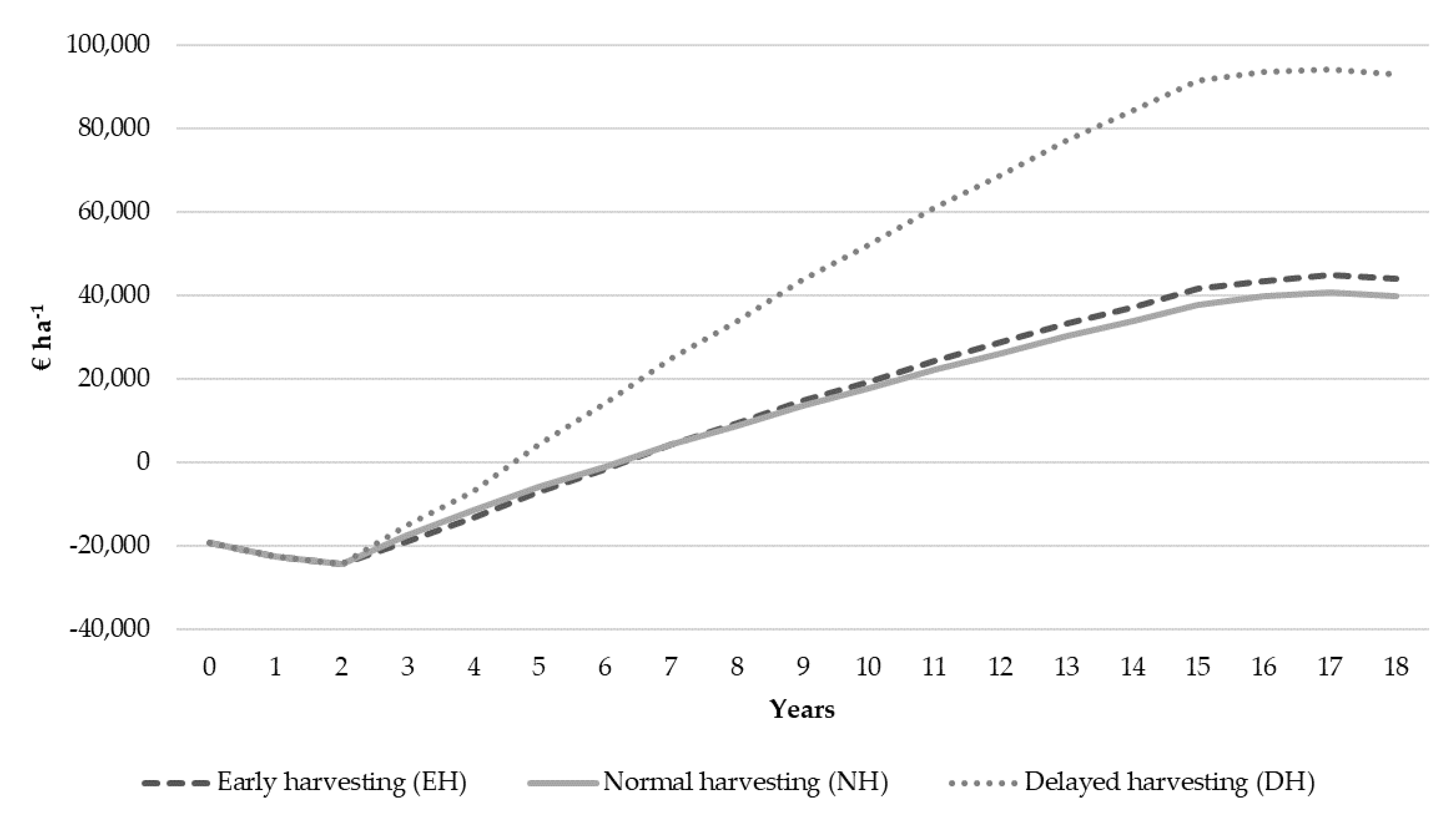

- Planting phase (PP), from the first to the second year, in which the vines are not productive and the only economic item is the planting cost;

- Growing phase (GP), from the third to the fourth year, in which vines and production grow, so that revenues increase more than proportionally compared to costs;

- Full production phase (FPP), from the fifth to the fifteenth year, in which vine growth is complete and production is stable, so that revenues and costs are constant;

- Decreasing production phase (DPP), from the sixteenth to the eighteenth year, in which vine ageing reduces the production, so that revenues decrease more than proportionally compared to costs.

2.1.2. Functional Units and System Boundaries

2.1.3. Evaluation Method and Impact Categories

2.2. LCC Analysis

- The annual total costs were evaluated at current prices. The total costs include specific costs (fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation water, fuel and lubricants, power) and other nonspecific operating costs concerning labor and mechanical operations, which were assessed considering the current hourly wage of workers for the manual operations and the current tariffs charged by agricultural service providers for the mechanical operations, respectively [44];

- The annual total revenues included the revenue from selling the table grapes, but excluded the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) direct aids [44];

- The discount rate was set at 4% considering alternative but similar investments in terms of type, market conditions, duration, and risk [96];

- The revenues per production model were calculated considering the average of farm gate prices on the marketplace of Bari (Italy) during the last five years, i.e., between 2014–2018 [2], namely 0.90 €/kg for the Mystery cultivar in the EH model, 0.55 €/kg for the Italia cultivar in the NH model, and 0.70 €/kg for the Italia cultivar in the DH model;

3. LCA Results

3.1. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Midpoint Analysis

- Irrigation and production/use of fertilizers in the cultivation phase;

- The use of galvanized steel cables and concrete poles in the construction phase.

3.2. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Endpoint Analysis

3.3. LCA Results Related to the Functional Unit of 1 Ton of Table Grape

3.4. LCC Results

3.4.1. Financial Analysis

- The DH model had the best financial performance;

- The EH and NH models had similar performance, but lower compared to the DH model.

3.4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| INPUT | Short Description | Unit of Measure | Construction of Tendone System | Planting Phase—PP | Growing Phase—GP | Full Production Phase—FPP | Decreasing Production Phase—DPP | Disposal of Tendone | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungicides (as active principle): | Penconazole | g | - | 0.00 | 240.00 | 1980.00 | 450.00 | - | 2670.00 |

| Cyproconazole | g | - | 0.00 | 160.00 | 1760.00 | 480.00 | - | 2400.00 | |

| Dimetomorf | g | - | 0.00 | 400.00 | 2200.00 | 600.00 | - | 3200.00 | |

| Myclobutanil | g | - | 0.00 | 42.00 | 462.00 | 63.00 | - | 567.00 | |

| Metalaxyl-m | g | - | 200.00 | 200.00 | 1100.00 | 300.00 | - | 1800.00 | |

| Copper | g | - | 1419.00 | 1419.00 | 7804.50 | 2128.50 | - | 12,771.00 | |

| Insecticides: | Methiocarb | g | - | 3604.00 | 3604.00 | 19,822.00 | 5406.00 | - | 32,436.00 |

| Chlorpyrifos-methyl | g | - | 1605.60 | 3211.20 | 22,077.00 | 4816.80 | - | 31,710.60 | |

| tau-Fluvalinate | g | - | 0.00 | 512.00 | 2,816.00 | 768.00 | - | 4096.00 | |

| Plant growth regulators: | Cytokin | l | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | 5.50 | 1.50 | - | 8.00 |

| Gibberellins | g | - | 0.00 | 16.00 | 88.00 | 24.00 | - | 128.00 | |

| Fertilizers: | Nitric nitrogen | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 30.48 | 167.64 | 45.72 | - | 243.84 |

| Ammoniacal nitrogen | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.32 | 7.26 | 1.98 | - | 10.56 | |

| Urea nitrogen | kg | 1000.00 | 7.00 | 14.00 | 77.00 | 21.00 | - | 1119.00 | |

| Phosphorus pentoxide | kg | 685.00 | 17.60 | 35.20 | 193.60 | 52.80 | - | 984.20 | |

| Calcium oxide | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 31.80 | 174.90 | 47.70 | - | 254.40 | |

| Magnesium oxide | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 19.20 | 105.60 | 28.80 | - | 153.60 | |

| Potassium oxide | kg | 1000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1000.00 | |

| Water: | Water for irrigation | mc | 0.00 | 1000.00 | 2000.00 | 11000.00 | 3000.00 | - | 17,000.00 |

| Water for phytosanitary treatments | mc | - | 6.40 | 14.40 | 96.80 | 24.00 | - | 141.60 | |

| Fuel: | Fuel | kg | 53.10 | 310.00 | 410.00 | 2,475.00 | 645.00 | 28.20 | 3921.30 |

| Lube oil | kg | 1.06 | 6.20 | 8.20 | 49.50 | 12.90 | 0.56 | 78.43 | |

| OUTPUT | Table grape | tons | - | 0 | 21.20 | 193.00 | 33.50 | 0.00 | 247.70 |

| INPUT | Short Description | Unit of Measure | Construction of Tendone System | Planting Phase—PP | Growing Phase—GP | Full Production Phase—FPP | Decreasing Production Phase—DPP | Disposal of Tendone | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungicides (as active principle): | Penconazole | g | - | 0.00 | 240.00 | 2,310.00 | 630.00 | - | 3180.00 |

| Cyproconazole | g | - | 0.00 | 160.00 | 1760.00 | 480.00 | - | 2400.00 | |

| Dimetomorf | g | - | 0.00 | 400.00 | 2200.00 | 600.00 | - | 3200.00 | |

| Myclobutanil | g | - | 0.00 | 42.00 | 693.00 | 189.00 | - | 924.00 | |

| Cyprodinil | g | - | 0.00 | 120.00 | 660.00 | 180.00 | - | 960.00 | |

| Metalaxyl-m | g | - | 200.00 | 200.00 | 1100.00 | 300.00 | - | 1800.00 | |

| Copper | g | - | 1419.00 | 1419.00 | 7804.50 | 2128.50 | - | 12,771.00 | |

| Insecticides: | Methiocarb | g | - | 3604.00 | 3604.00 | 19,822.00 | 5406.00 | - | 32,436.00 |

| Chlorpyrifos-methyl | g | - | 1605.60 | 3211.20 | 22,077.00 | 6021.00 | - | 32,914.80 | |

| tau-Fluvalinate | g | - | 0.00 | 512.00 | 2816.00 | 768.00 | - | 4096.00 | |

| Plant growth regulators: | Cytokin | l | - | 0.00 | 1.00 | 5.50 | 1.50 | - | 8.00 |

| Gibberellins | g | - | 0.00 | 16.00 | 88.00 | 24.00 | - | 128.00 | |

| Fertilizers: | Nitric nitrogen | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 30.48 | 167.64 | 45.72 | - | 243.84 |

| Ammoniacal nitrogen | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.32 | 7.26 | 1.98 | - | 10.56 | |

| Urea nitrogen | kg | 1000.00 | 7.00 | 14.00 | 77.00 | 21.00 | - | 1119.00 | |

| Phosphorus pentoxide | kg | 685.00 | 17.60 | 35.20 | 193.60 | 52.80 | - | 984.20 | |

| Magnesium oxide | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 19.20 | 105.60 | 28.80 | - | 153.60 | |

| Calcium oxide | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 31.80 | 174.90 | 47.70 | - | 254.40 | |

| Potassium oxide | kg | 1000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1000.00 | |

| Water: | Water for irrigation | mc | 0.00 | 1000.00 | 2,000.00 | 16,500.00 | 4500.00 | - | 24,000.00 |

| Water for phytosanitary treatments | mc | - | 6.40 | 19.20 | 132.00 | 36.00 | - | 193.60 | |

| Fuel: | Fuel | kg | 53.10 | 310.00 | 470.00 | 3168.00 | 864.00 | 28.20 | 4893.30 |

| Lube oil | kg | 1.06 | 6.20 | 9.40 | 63.36 | 17.28 | 0.56 | 97.87 | |

| OUTPUT | Table grape | tons | - | 0 | 42.50 | 350.00 | 63.50 | 0.00 | 456.00 |

| INPUT | Short Description | Unit of Measure | Construction of Tendone System | Planting Phase—PP | Growing Phase—GP | Full Production Phase—FPP | Decreasing Production Phase—DPP | Disposal of Tendone | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungicides (as active principle): | Penconazole | g | - | 0.00 | 240.00 | 2310.00 | 630.00 | - | 3180.00 |

| Cyproconazole | g | - | 0.00 | 160.00 | 3520.00 | 960.00 | - | 4640.00 | |

| Dimetomorf | g | - | 0.00 | 400.00 | 4400.00 | 1200.00 | - | 6000.00 | |

| Myclobutanil | g | - | 0.00 | 42.00 | 462.00 | 126.00 | - | 630.00 | |

| Cyprodinil | g | - | 0.00 | 600.00 | 5940.00 | 1620.00 | - | 8160.00 | |

| Metalaxyl-m | g | - | 200.00 | 200.00 | 1100.00 | 300.00 | - | 1800.00 | |

| Copper | g | - | 1419.00 | 2119.00 | 15,504.50 | 4228.50 | - | 23,271.00 | |

| Benzophenone | g | - | 0.00 | 250.00 | 6875.00 | 1875.00 | - | 9000.00 | |

| Fludioxonil | g | - | 0.00 | 320.00 | 3520.00 | 960.00 | - | 4800.00 | |

| Insecticides: | Methiocarb | g | - | 3604.00 | 3604.00 | 19,822.00 | 5406.00 | - | 32,436.00 |

| Chlorpyrifos-methyl | g | - | 1605.60 | 3211.20 | 17,661.60 | 4816.80 | - | 27,295.20 | |

| tau-Fluvalinate | g | - | 0.00 | 512.00 | 2816.00 | 768.00 | - | 4096.00 | |

| Tebufenozide | g | - | 0.00 | 200.00 | 1100.00 | 300.00 | - | 1600.00 | |

| Plant growth regulators: | Cytokin | l | - | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.50 | 1.50 | - | 9.00 |

| Gibberellins | g | - | 16.00 | 16.00 | 88.00 | 24.00 | - | 144.00 | |

| Fertilizers: | Nitric nitrogen | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 30.48 | 251.46 | 68.58 | - | 350.52 |

| Ammoniacal nitrogen | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.32 | 10.89 | 2.97 | - | 15.18 | |

| Urea nitrogen | kg | 1000.00 | 7.00 | 21.00 | 115.50 | 31.50 | - | 1175.00 | |

| Phosphorus pentoxide | kg | 685.00 | 17.60 | 52.80 | 290.40 | 79.20 | - | 1125.00 | |

| Magnesium oxide | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 19.20 | 158.40 | 43.20 | - | 220.80 | |

| Calcium oxide | kg | 0.00 | 0.00 | 31.80 | 262.35 | 71.55 | - | 365.70 | |

| Potassium oxide | kg | 1000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1000.00 | |

| Water: | Water for irrigation | mc | 0.00 | 1000.00 | 2500.00 | 22,000.00 | 6000.00 | - | 31,500.00 |

| Water for phytosanitary treatments | mc | - | 6.40 | 28.80 | 184.80 | 50.40 | - | 270.40 | |

| Fuel: | Fuel | kg | 53.10 | 310.00 | 636.00 | 4081.00 | 1113.00 | 28.20 | 6221.30 |

| Lube oil | kg | 1.06 | 6.20 | 12.72 | 81.62 | 22.26 | 0.56 | 124.43 | |

| OUTPUT | Table grape | tons | - | 0 | 42.50 | 395.00 | 55.50 | 0.00 | 493.00 |

References

- OIV. 2016. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/it/statistiques/ (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Ismea. 2019. Available online: http://www.ismea.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/9427 (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Istat. 6° Censimento Generale Dell’agricoltura. 2014. Available online: http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it/Index.aspx (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Seccia, A.; Santeramo, F.G.; Nardone, G. Trade competitiveness in table grapes: A global view. Outlook Agric. 2015, 44, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Green, K.; Belda, M.; Dewick, P.; Evans, B.; Flynn, A.; Mylan, J. Environmental Impacts of Food Production and Consumption: A Report to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; Manchester Business School: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nemecek, T.; Jungbluth, N.; Milà i Canals, L.; Schenck, R. Environmental impacts of food consumption and nutrition: Where are we and what is next? Int. J. Life Cycle Ass. 2016, 21, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Williams, J.; Daily, G.; Noble, A.; Matthews, N.; Gordon, L.; Wetterstrand, H.; DeClerck, F.; Shah, M.; Steduto, P.; et al. Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio 2017, 46, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acciani, C.; Sardaro, R. Percezione del rischio da campi elettromagnetici in presenza di servitù di elettrodotto: Incidenza sul valore dei fondi agricoli. Aestimum 2014, 64, 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Petrillo, F.; Sardaro, R. Urbanizzazione in chiave neoliberale e progetti di sviluppo a grande scala. Sci. Reg. 2014, 13, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040. Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14044. Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti, A.K.; Beccaro, G.L.; Bosco, S.; De Luca, A.I.; Falcone, G.; Fiore, A.; Iofrida, N.; Lo Giudice, A.; Strano, A. Life Cycle Assessment in the Fruit Sector; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, P.; Nei, D.; Orikasa, T.; Xu, Q.; Okadome, H.; Nobutaka, N.; Shiina, T. A review of life cycle assessment (LCA) on some food products. J. Food Eng. 2009, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, F.; Falcone, G.; Stillitano, T.; De Luca, A.I.; Gulisano, G.; Mistretta, M.; Strano, A. Life cycle assessment of olive oil: A case study in southern Italy. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, M.; D’Amico, M.; Celano, G.; Palese, A.M.; Scuderi, A.; Di Vita, G.; Pappalardo, G.; Inglese, P. Sustainability evaluation of Sicily’s lemon and orange production: An energy, economic and environmental analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, A.K.; Bruun, S.; Beccaro, G.L.; Bounous, G. A review of studies applying environmental impact assessment methods on fruit production systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2277–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, I. Environmental Management Tools for SMEs: A Handbook; European Environment Agency, Environmental Issues Series: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arzoumanidis, I.; Petti, L.; Raggi, A.; Zamagni, A. Life cycle assessment (LCA) for the agri-food sector. In Product—oriented Environmental Management System (POEMS)—Improving Sustainability and Competitiveness in the Agri-food Chain with Innovative Environmental Management Tools; Salomone, R., Clasadonte, M.T., Proto, M., Raggi, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- González-García, S.; Castanheira, E.G.; Dias, A.C.; Arroja, L. Environmental life cycle assessment of a dairy product: The yoghurt. Int. J. Life Cycle Ass. 2013, 8, 796–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, S.; Castanheira, E.G.; Dias, A.C.; Arroja, L. Using life cycle assessment methodology to assess UHT milk production in Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 442, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schau, E.; Fet, A. LCA studies of food products as background for environmental product declarations. Int. J. Life Cycle Ass. 2008, 13, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Forleo, M.B.; Giannoccaro, G.; Suardi, A. Environmental impact of cereal straw management: An on-farm assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2950–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Nicoletti, G.M. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of wine production. In Environmentally-Friendly Food Processing; Mattsson, B., Sonesson, U., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 306–326. [Google Scholar]

- Point, E.; Tyedmers, P.; Naugler, C. Life Cycle environmental impacts of wine production and consumption in Nova Scotia. Canada. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 27, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannone, R.; Miranda, S.; Riemma, S.; De Marco, J. Improving environmental performances in wine production by a life cycle assessment analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugani, B.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Benedetto, G.; Benetto, E. A comprehensive review of carbon footprint analysis is an extended environmental indicator in the wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 54, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, G.; Strano, A.; Stillitano, T.; De Luca, A.I.; Iofrida, N.; Gulisano, G. Integrated sustainability appraisal of wine-growing management systems through LCA and LCC methodologies. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2015, 44, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, A.M.; Pini, M.; Sassi, D.; Zerazion, E.; Neri, P. Effects of grape quality on the environmental profile of an Italian vineyard for Lambrusco red wine production. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3760–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, S.; Di Bene, C.; Galli, M.; Remorini, D.; Massai, R.; Bonari, E. Greenhouse gas emissions in the agricultural phase of wine production in the Maremma rural district in Tuscany. Italy. Ital. J. Agron. 2011, 6, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, G. Evaluation of Environmental Sustainability of Two Italian Wine Productions through the Use of the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Method. Master’s Thesis, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fusi, A.; Guidetti, R.; Benedetto, G. Delving into the environmental aspect of a Sardinian white wine: From partial to total life cycle assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 472, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, B.; Dias, A.C.; Machado, M. Life cycle assessment of the supply chain of a Portuguese wine: From viticulture to distribution. Int. J. Life Cycle Ass. 2013, 18, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Rey, P.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Moreira, M.; Feijoo, G. Comparative life cycle assessment in the wine sector: Biodynamic vs. conventional viticulture activities in NW Spain. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, P.; Fabozzi, F.J. Capital Budgeting: Theory and Practice; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Nova York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sardaro, R.; Pieragostini, E.; Rubino, G.; Petazzi, F. Impact of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis on profit efficiency in extensive dairy sheep and goat farms of Apulia, Southern Italy. Prev. Vet. Med. 2017, 136, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgroi, F.; Candela, M.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Foderà, M.; Squatrito, R.; Testa, R.; Tudisca, S. Economic and financial comparison between organic and conventional farming in Sicilian lemon orchards. Sustainability 2015, 7, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, F.; Foderà, M.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Tudisca, S.; Testa, R. Cost-benefit analysis: A comparison between conventional and organic olive growing in the Mediterranean Area. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 82, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Ninan, K.N. Social cost–benefit analysis of intensive versus traditional shrimp farming: A case study from India. Nat. Resour. Forum 2011, 35, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poot-López, G.R.; Hernández, J.M.; Gasca-Leyva, E. Analysis of ration size in Nile tilapia production: Economics and environmental implications. Aquaculture 2014, 420–421, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshak, G.L. Economic evaluation of capture-based bluefin tuna aquaculture on the US east coast. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2011, 26, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, N.; Sogoba, B.; Zougmore, R.; Howland, F.C.; Samake, O.; Bonilla-Findji, O.; Lizarazo, M.; Nowak, A.; Dembele, C.; Corner-Dolloff, C. Prioritizing investments for climate-smart agriculture: Lessons learned from Mali. Agric. Syst. 2017, 154, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardaro, R.; Grittani, R.; Scrascia, M.; Pazzani, C.; Russo, V.; Garganese, F.; Porfido, C.; Diana, L.; Porcelli, F. The Red Palm Weevil in the City of Bari: A First Damage Assessment. Forests 2018, 9, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardaro, R.; Faccilongo, N.; Roselli, L. Wind farms, farmland occupation and compensation: Evidences from landowners’ preferences through a stated choice survey in Italy. Energy Policy 2019, 133, 110885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gennaro, B.; Notarnicola, B.; Roselli, L.; Tassielli, G. Innovative olive-growing models: An environmental and economic assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 28, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, G.; Katerji, N.; Introna, M.; Hammami, A. Microclimate and plant water relationship of the “overhead” table grape vineyard managed with three different covering techniques. Sci. Hortic. 2004, 102, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, T. Viticultural Opportunities in Argentina; Wines and vines, Hiaring Company: San Rafael, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, A.G.; Wardle, D.A.; Naylor, A.P. Impact of training system, vine spacing, and basal leaf removal on riesling, vine performance, berry composition, canopy microclimate and vineyard labour requirements. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 1996, 47, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Novello, V.; Schubert, A.; Antonietto, M.; Boschi, A. Water relations of grapevine cv. Cortese with different training systems. Vitis 1992, 31, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Katerji, N.; Daudet, F.A.; Carbonneau, A.; Ollat, N. Etude à l’échelle de la plante entière du fonctionnement hydrique et phosynthétique de la vigne: Comparaison des systèmes de conduite traditionnel et an Lyre. Vitis 1994, 33, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, J.L.; McInnes, K.J.; Gesch, R.W.; Lascano, R.J.; Savage, M.J. Effects of trellising on the energy balance of a vineyard. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 1986, 81, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, J.L.; McInnes, K.J.; Savage, M.J.; Gesch, R.W.; Lascano, R.J. Soil and canopy energy balance in a west Texas vineyard. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 1994, 71, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, A.; Bravdo, B.; Gelobter, J. Gas-exchange and water relations in field-grown Sauvignon blanc grapevines. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 1994, 45, 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Trambouze, W.; Voltz, M. Measurement and modelling the transpiration of a Mediterranean vineyard. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 2001, 107, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel, T.; Rambal, S. Stomatal conductance of some grapevines growing in the fields under Mediterranean environment. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 1990, 51, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colapietra, M.; Cavuto, S. Prove di anticipazione dell’epoca di raccolta commerciale su uva da tavola cv. “Cardinal”. L’informatore Agrar. 1993, 96 (Suppl. 50), 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Colapietra, M.; Ranaldi, G.; Amico, G.; Tagliente, G. Diverse coperture su “Victoria” “Matilde” e “Sugraone”. L’informatore Agrar. 1997, 97 (Suppl. 50), 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy, A.; Lacirignola, C. Mediterranean Water Resources: Major Challenges Towards the 21st Century; CIHEAM-IAM: Bari, Italy, March 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Seccia, A.; Antonacci, D.; Pomarici, E. Proposta metodologica per l’analisi dei costi di produzione dell’uva da tavola. Bulletin de l’OIV 2009, 82, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti, A.K.; Beccaro, G.L.; Bruun, S.; Bosco, S.; Donno, D.; Notarnicola, B.; Bounous, G. LCA application in the fruit sector: State of the art and recommendations for environmental declarations of fruit products. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabi ver. 8. Available online: http://www.gabi-software.com/international/software/gabi-software/gabi/ (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Usetox 2.1. Available online: https://usetox.org/model/download/usetox2.1 (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Mackay, D. Multimedia Environmental Models: The Fugacity Approach; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- ECETOC. Ammonia Emissions to air in Western Europe. Technical Report no. 62; European Chemical Industry, Ecology & Toxicology Center: Brussels, Belgium, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- PCC. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Groups to the Fourth Assessment: Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brentrup, F.; Kusters, J.; Lammel, J.; Kuhlmann, H. Methods to estimate on-field nitrogen emission from crop production as an input to LCA studies in the agricultural sector. Intl. J. LCA 2000, 6, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, A.F. Compilation of a Global Inventory of Emissions of Nitrous Oxide; University of Wageningen: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bandino, G.; Dettori, S. Manuale di Olivicoltura; Regione Sardegna, 2000. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/it/document/view/14036060/manuale-di-olivicoltura-dipartimento-di-economia-e-sistemi-arborei (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Prasuhn, V. Erfassung der PO4-Austräge für die Ökobilanzierung SALCA Phosphor; Agroscope Reckenholz—Tänikon (ART), 2006. Available online: https://www.agroscope.admin.ch/agroscope/de/home/themen/umwelt-ressourcen/oekobilanzen/oekobilanz-methoden/oekobilanzmethode-salca.html#-1932315229 (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Freiermuth, R. SALCA Heavy Metal, Model to Calculate the Flux of Heavy Metals in Agricultural LCA; Final report; Agroscop Reckenholz-Tanikon (ART) research Institute: Zürich, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nemecek, T.; Kagi, T. Life Cycle Inventories of Swiss and European Agricultural Production Systems. Final report ecoinvent V2.0 NO. 15a. 2007. Available online: https://db.ecoinvent.org/reports/15_Agriculture.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Goedkoop, M.; Spriensma, R. Eco-Indicator 99. A Damage-Oriented Method for Life Cycle Impact Assessment: Methodology Report, 3rd ed.; Pré Consultants: Amersfoort (NL), The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hauschild, M.; Potting, J. Spatial differentiation in characterisation modelling-what difference does it make? In Proceedings of the 14th SETAC-Europe Annual Meeting, Prague, Czech Republic, 18–22 April 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ecoinvent Center. Ecoinvent Database, Version 3.0. Life Cycle Inventories. 2014. Available online: http://www.ecoinvent.ch (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Jolliet, O.; Margni, M.; Charles, R.; Humbert, S.; Payet, J.; Rebitzer, G. Presenting a new method IMPACT 2002+. A New Life Cycle Impact Assessment Methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Ass. 2003, 8, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, D.W.; Margni, M.; Amman, C.; Jolliet, O. Spatial versus non-spatial multimedia fate and exposure modeling: Insights for Western Europe. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, M.; Spriensma, R. The Eco-indicator 99: A Damage Oriented Method for Life Cycle Assessment, Methodology Report, 2nd ed.; Pré Consultants: Amersfoort (NL), The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Guinée, J.B.; Gorrée, M.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Kleijn, R.; van Oers, L.; Wegener Sleeswijk, A.; Suh, S.; Udo de Haes, H.A.; de Bruijn, H.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment: An Operational Guide to the ISO Standards; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht (NL), The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guinée, J.B.; Gorrée, M.; Heijungs, R. Handbook on Life Cycle Assessment: Operational Guide to the ISO Standards, Vol. 7; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 15686-5:2008. Buildings and Constructed Assets-Service Life Planning-Life Cycle Costing; International Organization for Standardization ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anson, M.J.P.; Fabozzi, F.J.; Jones, F.J. The Handbook of Traditional and Alternative Investment Vehicles: Investment Characteristics and Strategies; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kengatharan, L. Capital budgeting theory and practice: A review and agenda for future research. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2016, 3, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Souza, P.; Lunkes, R.J. Capital budgeting practices by large Brazilian companies. Contaduría y Administración 2016, 61, 514–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennouna, K.; Meredith, G.G.; Marchant, T. Improved capital budgeting decision making: Evidence from Canada. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusumilli, N.C.; Davis, S.; Fromme, D. Economic evaluation of using surge valves in furrow irrigation of row crops in Louisiana: A net present value approach. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 174, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetekamp, W. Net Present Value (NPV) as a Tool Supporting Effective Project Management. In Proceedings of the 6th IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems: Technology and Applications, 898–900, Article no. 6072902, Prague, Czech Republic, 15–17 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gailly, B. Developing Innovative Organizations: A Roadmap to Boost Your Innovation Potential; Palgrave Macmillan: Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.; Sawyers, R. Managerial Accounting: A Focus, 5th ed.; South Western. Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bonazzi, G.; Iotti, M. Interest coverage ratios (ICRs) and financial sustainability: Application to firms with bovine dairy livestock. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2014, 9, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, J.C.; MacCormack, J.J. Internal Rate of Return: A Cautionary Tale. 2014. Available online: http://www.cfo.com/printable/article.cfm/3304945 (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Daneshvar, S.; Kaleibar, M.M. The minimal cost-benefit ratio and maximal benefit-cost ratio. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Engineering System Management and Applications, ICESMA Article no. 5542690, Sharjah, UAE, 30 March–1 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zunino, A.; Borgert, A.; Schultz, C.A. The integration of benefit-cost ratio and strategic cost management: The use on a public institution. Espacios 2012, 33, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Bedecarratz, P.C.; López, D.A.; López, B.A.; Mora, O.A. Economic feasibility of aquaculture of the giant barnacle Austromegabalanus psittacus in southern Chile. J. Shellfish Res. 2011, 30, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoyan, S. The application of Monte Carlo computer simulation in economic decision making. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Application and System Modeling (ICCASM), 7, Taiyuan, China, V7-592, V7-595, 22–24, Taiyuan, China, 22–24 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clemen, R.T.; Ulu, C. Interior additivity and subjective probability assessment of continuous variables. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewy, P.; Nielsen, A. Modelling stochastic fish stock dynamics using Markov Chain Monte Carlo. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2003, 60, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, J.C.; Schafrick, I.C. The relevant internal rate of return. Eng. Econ. 2004, 49, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.; Foderà, M.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Tudisca, S.; Sgroi, F. Choice between alternative investments in agriculture: The role of organic farming to avoid the abandonment of rural areas. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 83, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasol, C.M.; Brun, F.; Mosso, A.; Rieradevall, J.; Gabarrell, X. Economic assessment and comparison of acacia energy crop with annual traditional crops in Southern Europe. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Trapani, A.M.; Sgroi, F.; Testa, R.; Tudisca, S. Economic comparison between offshore and inshore aquaculture production systems of European sea bass in Italy. Aquaculture 2014, 434, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, K.A.; Watanabe, W.O.; Dumas, C.F. Economic evaluation of a small-scale recirculating system for on growing of captive wild black sea bass Centropristis striata in North Carolina. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 2005, 36, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litskas, V.D.; Irakleous, T.; Tzortzakis, N.; Stavrinides, M.C. Determining the carbon footprint of indigenous and introduced grape varieties through Life Cycle Assessment using the island of Cyprus as a case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, K.C.; Bhattarai, S.P.; Midmore, D.J.; Oag, D.R.; Walsh, K.B. Temporal yield variability in subtropical table grape production. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 246, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedipour, P.; Asghari, M.; Abdollahi, B.; Alizadeh, M.; Danesh, Y.R. A comparative study on quality attributes and physiological responses of organic and conventionally grown table grapes during cold storage. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 247, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefola, M.; Pace, B.; Buttaro, D.; Santamaria, P.; Serio, F. Postharvest evaluation of soilless grown table grape during storage in modified atmosphere. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 2153–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttaro, D.; Serio, F.; Santamaria, P. Soilless greenhouse production of table grape under Mediterranean conditions. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012, 10, 641–645. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.E.; Dickey, D.A.; Frey, S.D.; Johnson, D.T. Increasing economic and environmental sustainability of table grapes using high tunnel advanced production. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1115, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, G.; Stillitano, T.; De Luca, A.I.; Di Vita, G.; Iofrida, N.; Strano, A.; Gulisano, G.; Pecorino, B.; D’Amico, M. Energetic and economic analyses for agricultural management models: The calabria PGI clementine case study. Energies 2020, 13, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vita, G.; Stillitano, T.; Falcone, G.; De Luca, A.I.; D’Amico, M.; Strano, A.; Gulisano, G. Can sustainability match quality citrus fruit growing production? An energy and economic balance of agricultural management models for ‘PGI clementine of calabria’. Agron. Res. 2018, 16, 1986–2004. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Unit of Measure | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Vineyard layout: | ||

| Shape of vineyard (rectangular) | m × m | 165 × 60 |

| Longitudinal and transversal rows | No. | 66 × 24 |

| Planting layout (distance between rows) | m × m | 2.50 × 2.50 |

| Young grafted vines (including transplant mortality) | No. ha−1 | 1584 (1614) |

| Tendone structure: | ||

| Wooden poles (height 2.80 m, diameter 11cm) | No. | 180 |

| Wooden poles (height 2.10 m, diameter 9 cm) | No. | 180 |

| Total timber | m3 | 360 |

| Prestressed reinforced concrete poles (height 2.80 m, square section 6 × 6 cm) | No. | 1404 |

| Concrete plinth foundations (ϕ 33 × 60 cm) | No. | 180 |

| Concrete plinth foundations (42 × 42 × 20 cm) | No. | 180 |

| Corner concrete plinth foundations (25 × 25 × 15 cm) | No. | 4 |

| Total concrete | tons | 34 |

| PVC pole covers | N. – kg | 1773 – 89.00 |

| Galvanized steel cables (ϕ 6.5 mm) | tons - m | 0.50 – 2000 |

| Galvanized steel cables (ϕ 5.5 mm) | tons - m | 0.10 – 2000 |

| Galvanized steel cables (ϕ 3.5 mm) | tons - m | 0.55 – 4000 |

| Galvanized steel cables (ϕ 2.7 mm) | tons - m | 0.60 – 8000 |

| Galvanized steel cables (ϕ 2.0 mm) | tons - m | 0.35 – 16,000 |

| Total steel | kg | 599 |

| Total galvanized surface | m2 | 107 |

| Plastic shelters | kg | 100.00 |

| Steel clips | kg | 10.00 |

| Plastic strings | tons | 1.50 |

| Irrigation system: | ||

| PE primary pipe (ϕ 110 mm) | m - kg | 50 – 158.50 |

| PE primary pipe (ϕ 90 mm) | m - kg | 100 – 213.00 |

| PE secondary pipe (ϕ 50 mm) | m - kg | 30 – 20.10 |

| PE secondary pipe (ϕ 40 mm) | m - kg | 140 – 60.20 |

| PE dripping pipe (ϕ 20 mm) | m - kg | 3300 – 561.00 |

| PVC tank pipe (ϕ 110 mm) | m - kg | 10 – 14.30 |

| PP drips (22 l hr−1) | No.; kg | 2700 – 13.5 |

| Plastic cover: | ||

| HDPE antihail nets (for all production models) | lifetime years. – kg | 7 – 242 |

| EVA films (only for EH and DH models) | lifetime years. – kg | 4 – 2440 |

| Parameter | Early Harvesting (EH) | Normal Harvesting (NH) | Delayed Harvesting (DH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivar (Typology) | Mystery (Seedless) | Italia (Seeded) | Italia (Seeded) |

| Planting density (Orchard layout) | 1584 vines ha−1 | 1584 vines ha−1 | 1584 vines ha−1 |

| (2.50 m × 2.50 m) | (2.50 m × 2.50 m) | (2.50 m × 2.50 m) | |

| Economic life (Years) | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| − Planting Phase—PP | 1st–2nd years | 1st–2nd years | 1st–2nd years |

| (two years) | (two years) | (two years) | |

| − Growing Phase—GP | 3rd–4th years | 3rd–4th years | 3rd–4th years |

| (two years) | (two years) | (two years) | |

| − Full Production Phase—FPP | 5th–15th years | 5th–15th years | 5th–15th years |

| (eleven years) | (eleven years) | (eleven years) | |

| − Decreasing Production Phase—DPP | 16th–18th years | 16th–18th years | 16th–18th years |

| (three years) | (three years) | (three years) | |

| Cover systems | Plastic film | Antihail net | Plastic film and antihail net |

| Mean yield (FPP—tons ha−1) | 17.55 | 31.82 | 35.91 |

| Mean yield (Economic life—tons ha−1) | 13.76 | 25.33 | 27.39 |

| Class quality * | “Extra” class | “Extra” class | “Extra” class |

| Parameter | Early Harvesting (EH) | Normal Harvesting (NH) | Delayed Harvesting (DH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter pruning (Period) | Manual | Manual | Manual |

| (December) | (December) | (January) | |

| Shredding of pruning residues (Period) | By tractor and shredder | By tractor and shredder | By tractor and shredder |

| (December) | (December) | (January) | |

| Plastic net opening (Period) | Manual | Manual | Manual |

| (April) | (April) | (April) | |

| Plastic films opening (Period) | By tractor and stretching machine | - | By tractor and stretching machine |

| (February) | (April) | ||

| Spring pruning (Period) | Manual | Manual | Manual |

| (April) | (May) | (May) | |

| Defoliation (Period) | Manual | Manual | Manual |

| (May) | (June) | (June) | |

| Small acini detachment (Period) | - | Manual | Manual |

| (June) | (June) | ||

| Winter fertilization with granular chemical fertilizers (Period) | By spreader | By spreader | By spreader |

| (February) | (February) | (February) | |

| Fertirrigation technique with liquid chemical fertilizers (N. of interventions and period) | Drip irrigation | Drip irrigation | Drip irrigation |

| (2 times year 1, May–June) | (2 times year 1, May–June) | (2 times year 1, May–June) | |

| Irrigation technique (N. of interventions and period) | Drip irrigation | Drip irrigation | Drip irrigation |

| (2 times year 1, May–June) | (4 times year 1, May–July) | (5 times year 1, May–September) | |

| Weed control (Period) | Mechanical tillage and herbicides spread by tractor and atomizer | Mechanical tillage and herbicides spread by tractor and atomizer | Mechanical tillage and herbicides spread by tractor and atomizer |

| (February–July) | (April–July) | (February–September) | |

| Pest control (Period, Frequency) | Conventional technique using tractor and atomizer | Conventional technique using tractor and atomizer | Conventional technique using tractor and atomizer |

| (April–May, Weekly) | (April–August, Weekly) | (April–November, Weekly) | |

| Harvest method (Period) | Manual | Manual | Manual |

| (June) | (September) | (December) | |

| Plastic net closing (Period) | Manual | Manual | Manual |

| (September) | (October) | (January) | |

| Plastic films closing (Period) | By tractor and stretching machine | - | By tractor and stretching machine |

| (September) | (January) |

| Midpoint Impact Categories- | Units | EH | NH | DH | Endpoint Damage Category | Units | EH | NH | DH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcinogens | kg C2H3Cl equiv to air | 1.29 × 103 | 3.69 × 102 | 2.65 × 103 | Human Health | DALY | 2.49 × 100 | 3.07 × 10−1 | 3.40 × 100 |

| Noncarcinogens | kg C2H3Cl equiv to air | 8.66 × 105 | 1.03 × 105 | 1.18 × 106 | |||||

| Respiratory effects | kg PM2.5 equiv to air | 9.20 × 101 | 2.54 × 101 | 1.16 × 102 | |||||

| Ionizing radiation | Bq C-14 equiv to air | 9.43 × 105 | 1.58 × 105 | 1.49 × 106 | |||||

| Ozone layer depletion | kg CFC-11 equiv to air | 4.55 × 10−3 | 7.70 × 10−4 | 4.54 × 10−3 | |||||

| Photochemical oxidation | kg C2H4 equiv to air | 3.82 × 101 | 9.95 × 100 | 5.02 × 101 | |||||

| Aquatic ecotoxicity | kg TEG equiv to water | 6.88 × 109 | 7.97 × 108 | 8.98 × 109 | Ecosystem Quality | PDF*m2*yr | 6.99 × 107 | 8.21 × 106 | 9.42 × 107 |

| Terrestrial ecotoxicity | kg TEG equiv to soil | 8.69 × 109 | 1.02 × 109 | 1.17 × 1010 | |||||

| Terrestrial acid./nutri. | kg SO2 equiv to air | 2.50 × 103 | 7.63 × 102 | 3.31 × 103 | |||||

| Land occupation | m2*year equiv | 3.87 × 103 | 1.14 × 103 | 6.57 × 103 | |||||

| Aquatic acidification | kg SO2 equiv to air | 2.61 × 102 | 9.52 × 101 | 3.06 × 102 | |||||

| Aquatic eutrophication | kg PO4 equiv to water | 8.69 × 109 | 1.02 × 109 | 1.17 × 1010 | |||||

| Global warming 500 year | kg CO2 equiv to air | 1.08 × 105 | 3.64 × 104 | 1.49 × 105 | Climate Change | kg CO2 | 1.08 × 105 | 3.64 × 104 | 1.49 × 105 |

| Nonrenewable energy | MJ | 1.52 × 106 | 3.28 × 105 | 2.21 × 106 | |||||

| Mineral extraction | MJ surplus | 1.49 × 104 | 2.05 × 103 | 2.03 × 104 | Resources | MJ primary | 1.53 × 106 | 3.30 × 105 | 2.23 × 106 |

| Impact Categories | EH | NH | DH | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | A | B | C | D | A | B | C | D | |

| Carcinogens | 102% | −11% | 20% | −11% | 45% | 20% | 72% | −37% | 83% | 12% | 10% | −5% |

| Noncarcinogens | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 99% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Respiratory effects | 76% | 9% | 14% | 1% | 32% | 13% | 52% | 3% | 84% | 4% | 12% | 0% |

| Ionizing radiation | 73% | 22% | 7% | −2% | 55% | 19% | 43% | −17% | 73% | 24% | 5% | −2% |

| Ozone layer depletion | 78% | 17% | 4% | 1% | 53% | 23% | 24% | 0% | 105% | −9% | 4% | 0% |

| Photochemical oxidation | 49% | 36% | 15% | 0% | 22% | 19% | 59% | 0% | 51% | 37% | 12% | 0% |

| Aquatic ecotoxicity | 99% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 98% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Terrestrial ecotoxicity | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Terrestrial acid./nutri. | 75% | 6% | 18% | 1% | 31% | 6% | 59% | 4% | 82% | 3% | 14% | 1% |

| Land occupation | 83% | −1% | 22% | −4% | 37% | 1% | 74% | −12% | 82% | 7% | 13% | −2% |

| Aquatic acidification | 64% | 13% | 23% | 0% | 23% | 13% | 64% | 0% | 85% | −5% | 20% | 0% |

| Aquatic eutrophication | 69% | 25% | 5% | 1% | 44% | 25% | 31% | 0% | 71% | 25% | 4% | 0% |

| Global warming 500 year | 59% | 20% | 15% | 6% | 18% | 13% | 33% | 36% | 65% | 20% | 11% | 4% |

| Nonrenewable energy | 64% | 29% | 10% | −3% | 37% | 34% | 47% | −18% | 66% | 29% | 7% | −2% |

| Mineral extraction | 80% | 16% | 4% | 0% | 65% | 7% | 28% | 0% | 81% | 16% | 3% | 0% |

| Environmental Indexes /(Net Calorific Value) NCV | Units | EH | NH | DH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abiotic Depletion (ADP elements) | kg Sb equiv | 4.47 × 10−3 | 1.33 × 10−3 | 2.80 × 10−3 |

| Abiotic Depletion (ADP fossil) | MJ | 5.69 × 103 | 6.78 × 102 | 4.44 × 103 |

| Acidification Potential (AP) | kg SO2 equiv | 1.65 × 100 | 2.67 × 10−1 | 1.05 × 100 |

| Eutrophication Potential (EP) | kg Phosphate equiv | 6.12 × 10−1 | 6.70 × 10−2 | 4.54 × 10−1 |

| Global Warming Potential (GWP 100 years) | kg CO2 equiv | 4.56 × 102 | 8.18 × 101 | 3.32 × 102 |

| Global Warming Potential (GWP 100 years), excl biogenic carbon | kg CO2 equiv | 4.38 × 102 | 7.00 × 101 | 3.21 × 102 |

| Ozone Layer Depletion Potential (ODP, steady state) | kg R11 equiv | 1.84 × 10−5 | 1.69 × 10−6 | 9.86 × 10−6 |

| Photochem. Ozone Creation Potential (POCP) | kg Ethene equiv | 1.05 × 10−1 | 4.67 × 10−3 | 7.36 × 10−2 |

| Energy (net calorific value) | MJ | 1.27 × 104 | 1.44 × 103 | 9.74 × 103 |

| Production Models | NPV | IRR | DBCR | DPBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EH | 42,104.77 | 18.6% | 1.38 | 8.56 |

| NH | 37,222.38 | 12.7% | 1.26 | 8.15 |

| DH | 94,372.16 | 31.2% | 1.74 | 5.14 |

| NPV | IRR | DBCR | DPBP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EH | ||||

| Min. | 12,372.48 | 7.3% | 1.23 | 5.0 |

| Mean | 53,825.85 | 22.8% | 1.54 | 7.1 |

| Max | 106,170.62 | 36.4% | 2.11 | 16.7 |

| Std. dev. | 18,551.23 | 2.2% | 0.22 | 1.7 |

| NH | ||||

| Min. | −27,916.33 | 4.2% | 0.76 | 6.3 |

| Mean | 25,284.28 | 12.7% | 1.10 | 8.3 |

| Max | 73,017.01 | 21.4% | 1.65 | 17.7 |

| Std. dev. | 21,625.38 | 2.2% | 0.19 | 5.6 |

| DH | ||||

| Min. | 22,374.73 | 9.0% | 1.21 | 3.7 |

| Mean | 89,914.60 | 30.0% | 1.77 | 5.5 |

| Max | 167,482.85 | 51.0% | 2.43 | 12.4 |

| Std. dev. | 28,833.63 | 5.6% | 0.36 | 1.3 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roselli, L.; Casieri, A.; de Gennaro, B.C.; Sardaro, R.; Russo, G. Environmental and Economic Sustainability of Table Grape Production in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093670

Roselli L, Casieri A, de Gennaro BC, Sardaro R, Russo G. Environmental and Economic Sustainability of Table Grape Production in Italy. Sustainability. 2020; 12(9):3670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093670

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoselli, Luigi, Arturo Casieri, Bernardo Corrado de Gennaro, Ruggiero Sardaro, and Giovanni Russo. 2020. "Environmental and Economic Sustainability of Table Grape Production in Italy" Sustainability 12, no. 9: 3670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093670

APA StyleRoselli, L., Casieri, A., de Gennaro, B. C., Sardaro, R., & Russo, G. (2020). Environmental and Economic Sustainability of Table Grape Production in Italy. Sustainability, 12(9), 3670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093670