Abstract

Kigali city authorities have recently adopted an in-kind compensation option to mitigate some patterns of spatial injustices, reflected in the displacement of expropriated real property owners towards urban outskirts, where they can afford new properties using the in-cash compensation they receive. This study assesses whether this form of compensation promotes a spatially just and inclusive urban (re)development. It applies an evaluative framework comprising a series of indicators connected to three dimensions (rules, processes, and outcomes) of spatial justice and its four forms consisting of procedural, recognitional, redistributive, and intra-generational justice. It relies on data collected through field surveys and a review of literature on expropriation and urban (re)development processes in Kigali city. The findings reveal that the adopted in-kind compensation exhibits some aspects of spatial justice connected with the access to decent houses, basic urban amenities, and increased tenure security. However, these findings unveil deficiencies in procedural, recognitional, redistributive, and intra-generational justice, portrayed in the lack of negotiation on the compensation option, non-participation of expropriated property owners in their resettlement process, overcrowding conditions of the new houses, and loss of the main sources of incomes. Some options for a better implementation of the in-kind compensation are suggested. Two strands of procedural and recognitional justice, namely negotiation and community participation, are central to their successful implementation.

1. Introduction

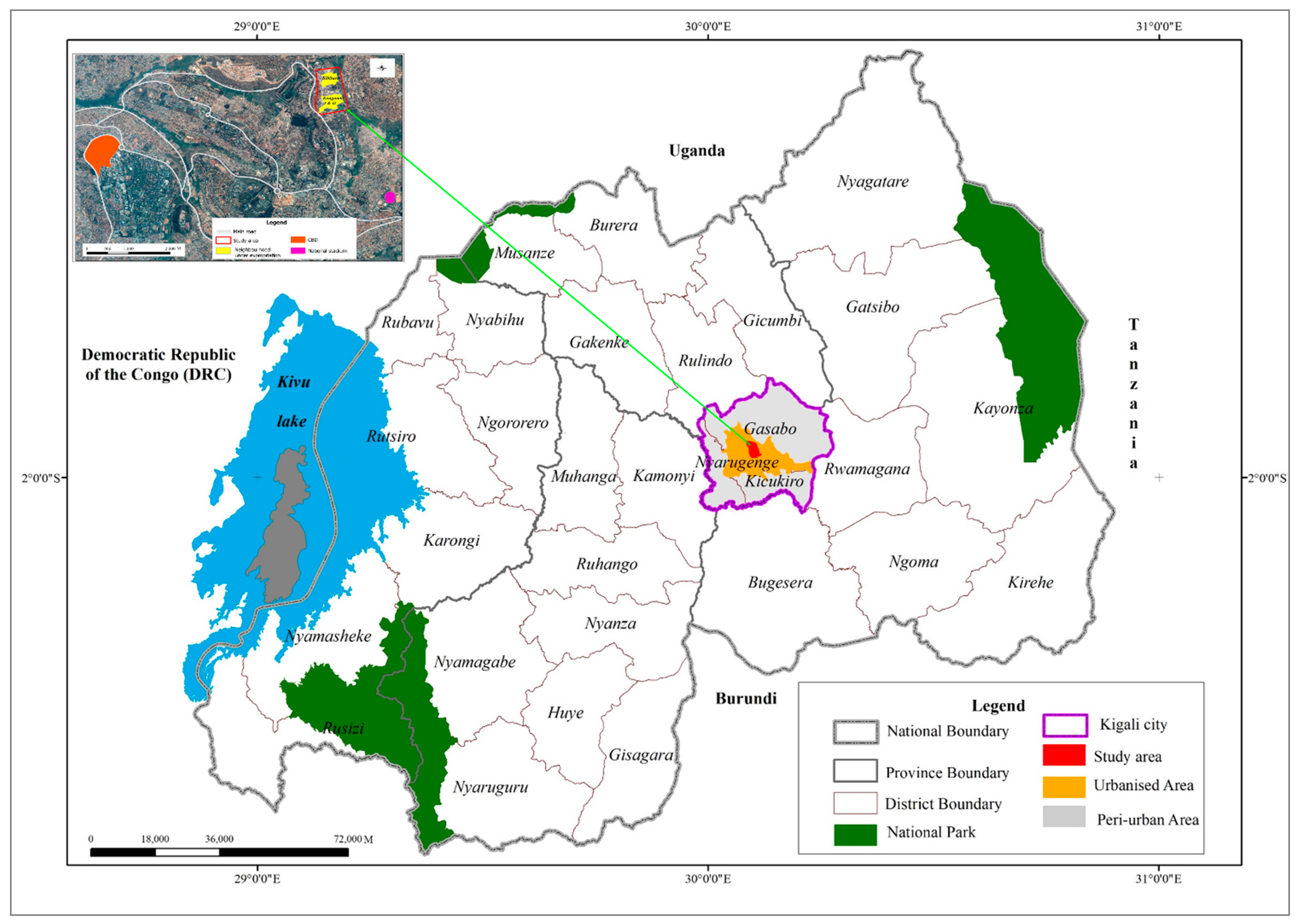

Kigali, the capital city of Rwanda (located in East Africa, as shown in Figure A1), has been undergoing different processes of urban re-development, alongside the implementation of its conceptual and detailed master plans, adopted from 2008 to 2013 [1]. These processes consist of clearing informal settlements and old structures and providing basic amenities and services, in a bid to improve the economic, physical, social, and environmental conditions of the city. Their implementation has been preceded by the acquisition of large tracts of land and other assets incorporated thereon, such as residential buildings through expropriation [2,3]. Expropriation means a compulsory acquisition of individuals’ real properties by the State in the public interest. This should be done in accordance with procedures provided by law and subject to fair and prior compensation, which can consist of the monetary form or other real properties [4]. The latter is referred to as in-kind compensation in this paper. Alongside the implementation of Kigali city master plans, the practice of expropriation has mainly targeted informal settlements [2]. The processes of urban space (re)organization, which include the clearance of these settlements, have been decried by spatial justice scholars for producing spatial injustices through forcing their inhabitants (poor and low-income people) out of the urbanised areas and depriving them of access to basic urban resources [5,6]. Despite the in-cash compensation paid to expropriated property owners in Kigali city, these processes result in their displacement towards urban fringes, as they can hardly afford new houses in the planned urban neighbourhoods [4,7]. This displacement trend is discussed in Section 2 of this paper.

In seeking for better urban (re)development options that counteract the exclusionary effects of expropriation, Kigali City Council and its partners have recently decided to implement the in-kind compensation for expropriated property owners [4], through their resettlement in planned urban neighbourhoods [8]. This resettlement is embodied in the goals related to inclusive urban (re)development, as stated in the national strategies for socio-economic development and various policies, including the Vision 2020; the national strategy for transformation (NST1) [9]; the national urbanisation policy [10]; and the national housing policy [11]. As for goals, they include the promotion of living conditions of all urban dwellers through the increased access to decent housing, basic amenities and services, and prevention of urban dynamics that may be deterrent to spatial inclusion [10]. Achieving this inclusion embraces the promotion of diversity in the urban space and participation of all its inhabitants, including the poor and low-income groups, in making and implementing regulations and plans related to the development of their lived spaces [12]. As suggested by proponents of an inclusive and just city, meeting the aforementioned goals necessitates decreasing the displacement of urban dwellers from their neighbourhoods, through the increased consideration of spatial justice aspiration in rules and processes related to urban space (re)organisation [5,6,13].

Along these lines, spatial justice consists of the spatial aspect of social justice within any geographical space, which is the product of social relations and interactions among various actors (including the local community) who make decisions about who can access and use its resources [5,14]. Generally, spatial justice is envisioned as the application of effective rules and processes related to the management of geographical space with the aim to achieve just outcomes, such as equality in access and use of its resources for all people towards improving their living conditions [15]. Various urban management approaches exist to curb spatial injustices, which are manifested in inequalities in access to basic resources and neighbourhood segregation [14,16]. During the implementation of the in-kind compensation through the resettlement of expropriated real property owners, spatial justice aspects entail increased recognition and respect of their rights to land and housing [17,18]. In the Rwandan context, respect of these rights for all people is stipulated in article 34 of the national constitution. This article states that private property is inviolable and shall not be encroached upon, except when it is required by public interest. Yet, it has be to be carried out according to legal procedures [19]. The 2015 expropriation law grants the State the power to interfere in private property rights for a public interest, provided that there is a payment of a fair compensation, that is, an indemnity that is equivalent to the market value of the land and related properties. The compensation can be paid in a monetary form or in any other form mutually agreed upon by an expropriator and an expropriated person [20]. In addition, national housing and human settlement policies recognise the rights of local communities to participate in making and implementing decisions and plans related to urban (re)development, including the resettlement of displaced property owners [11].

Community participation in urban (re)development processes is a prerequisite for meeting processual and distributive aspects of spatial justice [6,21]. In expropriation and resettlement processes, processual aspects encompass negotiation on the compensation option between the expropriating agencies and property owners, and their direct collaboration in designing and implementing the resettlement plans. The distributive aspect includes the compensation for the acquired real properties at the market value; improved access to basic urban amenities and services for the resettled property owners; and their opportunities to reconstitute their livelihoods, that is, access to new jobs or income-generating activities [17,18]. These aspirations are also well reiterated in the current regulations related to Kigali city (re)development, which legitimise resettlement as the compensation option for expropriated property owners [20]. However, recent studies on Kigali city (re)development processes point out that expropriated people have been sceptical about the advantages of this form of compensation [8] because it may not be carried out in a just way [22]. Nevertheless, there are no studies that fully ascertain justice aspects from the implementation of this form of compensation [4]. This study is, therefore, a contribution to bridge this knowledge gap. Its main objective is to evaluate if the in-kind compensation for expropriated real properties in Kigali city exhibits some trends of spatial justice in the related regulations as well as their implementation processes and outcomes. The pursuit of this objective was guided by the following research questions:

- (1)

- Do regulations and practices governing the in-kind compensation option in Kigali city promote spatial justice?

- (2)

- How can this compensation option be effectively applied to advance spatial justice for expropriated real property owners in Kigali city?

The findings of this research can inform policy makers and agencies engaged in Kigali city (re)development on the degree to which they can attain their objectives of promoting inclusive urban (re)development. Furthermore, it can help to identify different aspects for improvement during the resettlement of displaced property owners. This paper is structured into six sections. After this introduction, Section 2 highlights the drivers for adopting the resettlement option as the form of compensation for expropriated property owners in Kigali city. Section 3 discusses the theoretical foundation of spatial justice. Section 4 discusses the evaluative framework. Section 5 provides details on data sources and research methods. Section 6 presents and discusses our findings. At the end, a general conclusion is drawn.

2. Drivers for Adopting the In-Kind Compensation in Kigali City: Promoting Inclusive Urban (Re)Development through Decreasing Spatial Injustices

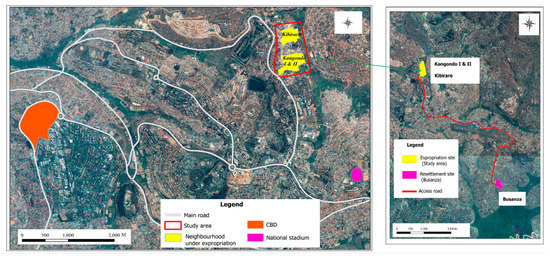

In-kind compensation can be a string to spatial aspects of injustices when it results in the confinement of the poor and low-income expropriated property owners, in particular localities deprived of access to basic infrastructure and services, even if they receive a fair compensation. These injustices can also be attributed to inequity associated with the payment of unfair compensation, which makes it difficult for the expropriated property owners to improve their living conditions and quality of life after expropriation [23]. An in-depth examination of the problems faced by expropriated property owners in Kigali city reveals these features of spatial injustices [24]. They are reflected in low development patterns and disparities in access to basic amenities and services including water, electricity, transportation network, education, and health and sanitation facilities between the former neighbourhoods and new residential areas of expropriated property owners, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Displacement patterns and trends of access to basic urban amenities and services for expropriated property owners in Kigali city. Data source: Government of Rwanda [25], Norwegian People’s Aid and Rwanda Civil Society Platform [24], and Uwayezu and de Vries [4]. CBD, central business district.

Figure 1 shows the main urban neighbourhoods of Kigali city where different processes of expropriation have been carried out from 2008 to 2019. It also shows the numbers of expropriated households that have been displaced towards the urban fringes where they could afford other houses, the prices of which are relatively commensurate with the in-cash compensations that they receive [4]. Generally, these households move from the neighbourhoods where access to basic amenities or services is “very good” to new residential areas where this access is “limited”, in relation to the accessibility indicators defined in the regulations related to urban planning and buildings development in Rwanda [25]. According to these regulations, the thresholds that are taken into account to assess the quality of access to any of these basic amenities and services are defined in Table A1.

From the data in Figure 1 and Table A1, it is obvious that in-cash compensation pushes expropriated real property owners in Kigali city towards areas with limited access to basic urban amenities. In their new residential neighborhoods, these people have been putative actors of informal settlements’ proliferation, and related environmental degradation, which increasingly become a challenge for sustainable urban (re)development [4,8]. Some of these informal settlements are located in high-risk zones whose land slope is greater than 30%, which should be cleared alongside the implementation of the current Kigali city master plan [26,27]. For this reason, new settlers as well as the existing inhabitants are perpetually risking displacement. Although clearing these settlements involves expropriation, decision-makers find the perpetual process of expropriation very expensive [4]. A practical and suitable option for mitigating the displacement effect induced by the in-cash compensation would be to relocate expropriated property owners in planned urban neighborhoods. This would be an alternative form of compensation, which is also allowed under the general framework of inclusive urban (re)development in Rwanda [4,10]. In addition, this form of compensation can contribute to the achievement of the target of the Rwandan Government to increase the current rate of urban population from 18% to 35% by 2024, in a bid to promote a socio-economic development in the context of ongoing urbanisation [9]. Therefore, the adoption of in-kind compensation can help to achieve these aspects of spatial justice, related to the integration of all people in the urban fabric and increased access to basic urban amenities and services. The next section connects this form of compensation to features of spatial justice.

3. Framing Spatial Justice from the Resettlement of Expropriated Property Owners

The need to improve spatial justice in rules and processes of urban (re)development is expressed in the global agenda of inclusive cities [28,29]. From a welfare perspective, advocates of spatial justice plead for increased recognition of rights for all urban dwellers to urban space, as well as access and use of its resources, according to their needs and socio-economic aspirations [5,16]. According to Lefebvre [6], urban space (re)development operations can support spatial justice if they include specific measures meant to reduce spatial inequalities and prevent deprivation to basic urban resources for all urban dwellers. This requires the pursuit of the four forms of spatial justice (i.e., procedural, recognitional, redistributive, and intra-generational justice [14,30,31]) during the implementation of different urban (re)development programmes, including the resettlement of displaced urban dwellers [17,32].

Procedural justice conceptually adheres to spatial management principles. It is embedded in rules and processes related to the use, access, or allocation of spatial resources. It is vividly captured in the participation and inclusion of all spatial resource owners (and users) in making decisions that affect their rights on these resources [30,33]. When urban (re)development can result in expropriation and compensation, including the resettlement processes of the affected property owners, pursuing procedural justice requires the application of clear procedures such as their participation in planning and implementation of these processes, so that their rights to housing can be recognised and re-established [21,30]. Procedural justice also embraces voice and hearing [34], which permits shaping the resettlement site according to the needs, interests, and livelihoods of the resettled people [17]. For this to happen, it is crucial to combine procedural justice with recognitional justice.

Recognitional justice embraces the respect and recognition of property owners’ rights to land, housing, and basic amenities when implementing expropriation projects [32]. When the compensation option is adopted for resettlement, these rights are sought in both rules guiding expropriation. Recognitional justice is about treating all resettled property owners in a just way, in accordance with the international and/or national guidelines and mechanisms applied to acquire real private property. The rights and needs of these property owners are recognised if they are actively involved in the implementation of their resettlement in partnership with government officials who make decisions related to the urban space management [35]. In a nutshell, recognitional justice through participation empowers and benefits expropriated property owners and allows for a fair compensation and access to basic urban amenities and services in the resettlement site.

Redistributive justice embraces all processes of redistributing spatial resources or allocating use rights based on the needs of all users of the urban space. This could overcome material deprivation and/or decrease spatial inequalities [36]. This form of spatial justice relates mainly to the implementation of rules that guide these processes and determine their outcomes. In expropriation, redistributive justice stands for fair compensation for affected property owners, proportionally to their losses. This requires an increased consideration of human dignity so that expropriation does not result in deprivation of resources and/or deepening poverty for these people [37].

Intra-generational justice advances welfare for all urban dwellers, through the recognition of their basic rights when implementing urban (re)development projects. During expropriation and resettlement processes, welfare coalesces in fair restitution of individuals’ rights to housing, basic urban amenities, and services [38]. This means that these processes equally benefit all categories of property owners [39]. The pursuit of intra-generational justice specifically requires to consider the conditions of the worst-off or least disadvantaged groups when implementing these processes. Intra-generational justice, therefore, promotes effective allocation of material resources among a generation of people from different socio-economic statuses, so that the position of the worst-off people is improved or does not deteriorate [17].

The four forms of spatial justice share similar normative values, including active participation of expropriated property owners in resettlement processes, recognition and restoration of rights to basic material resources and socio-economic opportunities, and reconstitution of their livelihoods. In the following section, we present the evaluative framework to assess whether in-kind compensation for expropriated property owners in Kigali city is aligned with these values.

4. Evaluative Framework

Guidelines, standards, and recommendations developed by international organizations (such as the Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations, and World Bank) in relation to the compulsory real property acquisition call for the provision of fair compensation for the affected property owners [40,41,42]. Table 1 summarises these guidelines and mechanisms, and connects them to the forms of spatial justice discussed above, whose main aspiration encompasses a just resettlement process of displaced property owners.

Table 1.

Key aspects of guidelines and mechanisms for the implementation of resettlement as a compensation form during expropriation.

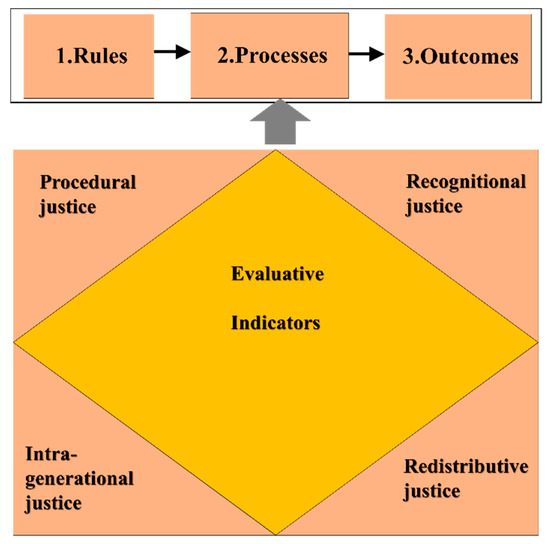

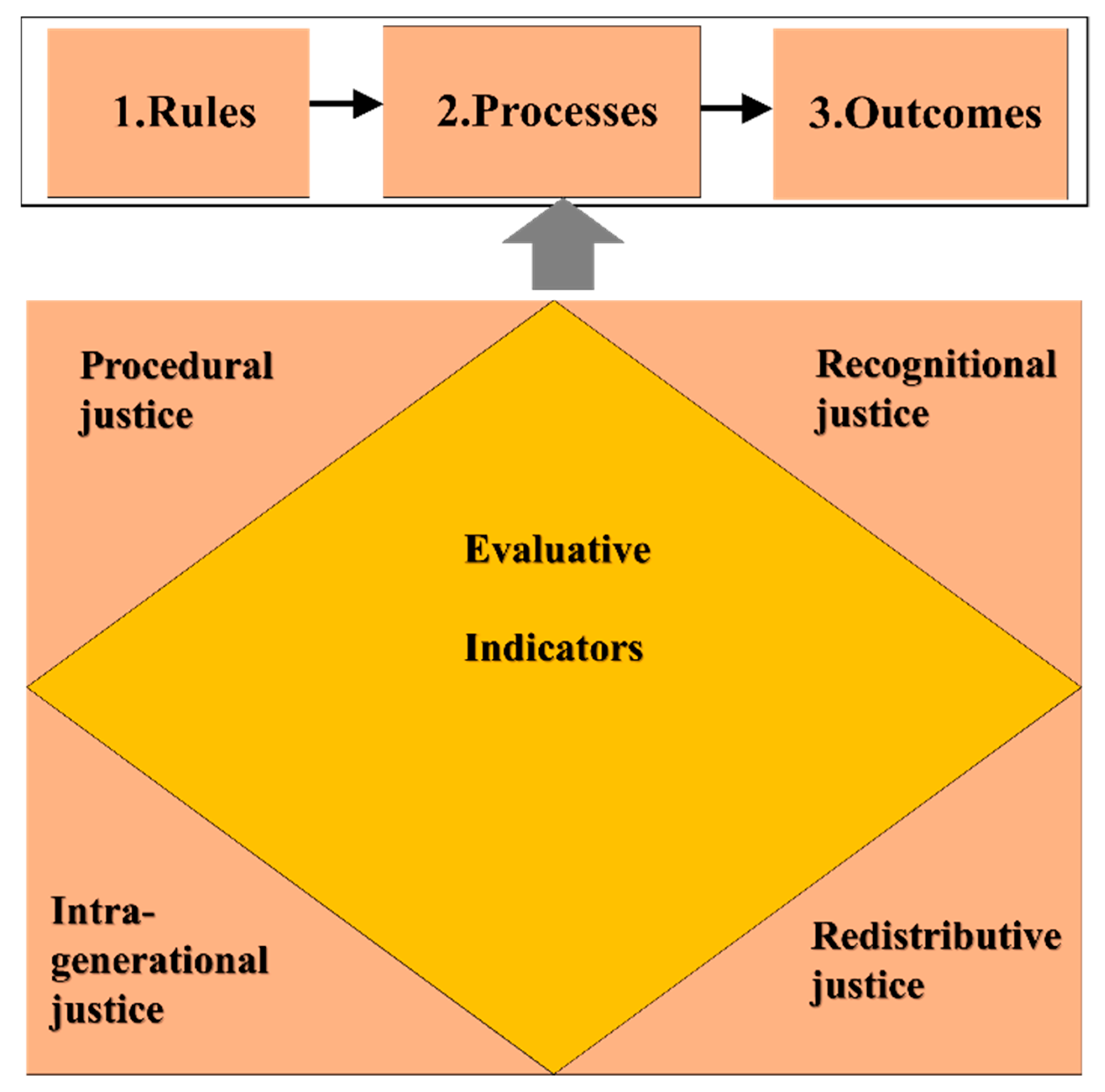

By connecting the four forms of spatial justice with these guidelines and mechanisms, we selected indicators to assess trends of spatial justice when resettling expropriated property owners in Kigali city. The selection of these indicators relies on the framework developed by Uwayezu and de Vries [17]. The assessment consisted of investigating if rules in use and their implementation processes permit expropriated property owners to have access to decent houses, urban amenities, and services, in order to pursue their livelihoods and promote their security of tenure [17,32]. Figure A2 shows the applied evaluative framework, which comprises three dimensions (rules, processes, and outcomes) and indicators connected to four forms of spatial justice. The rules dimension embraces different national policies and laws, including the 2008 national land policy and urban housing policy, the 2012 law relating to planning of land use and development, the 2013 law governing land, the 2015 law relating to expropriation in the public interest, and the national urbanization policy [10,11,20,49,50], which govern land management in Rwanda. There are also local zoning regulations and Kigali city master plans, adopted from 2008 to 2013, that guide land use and spatial organisation of this city [51]. The processes dimension corresponds to different action plans and activities related to the implementation of these rules. The outcomes dimension is associated with redistributive effects of the implemented action plans and activities performed in line with the resettlement process [4,17]. These outcomes relate to access to decent housing, basic amenities, jobs or income-generating activities, and other opportunities that help expropriated property owners to pursue their livelihoods. The applied evaluative indicators covering these aspects are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Indicators for measuring spatial justice in the in-kind compensation for expropriated real property in Kigali city. Adapted from Uwayezu and de Vries [17].

5. Data Sources and Methods

In this section, we present the study area and discuss methods applied in collecting and analysing the required data for this study. Data collection was carried out in three phases: January–March 2018; January–February 2019; and June 2019. During the first phase, the inventory and valuation of real properties to be expropriated was carried out by property valuers hired by Kigali city and Gasabo district, which are the expropriating agencies in this case. Local leaders and district authorities informed property owners about their resettlement process as compensation option. We collected data on the motivation for adopting the in-kind compensation and perceptions of property owners on this compensation option. During the second and third phases, the construction of houses that will be allocated to these people took place. We collected data about the location of their resettlement site, characteristics of these houses, and availability of socio-economic infrastructure and services. It is worth noting that the construction of some houses was in the final stage and their recipients were expected to move in before the end of June 2020.

5.1. Study Site

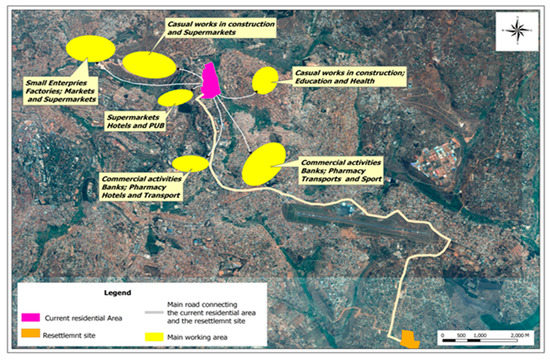

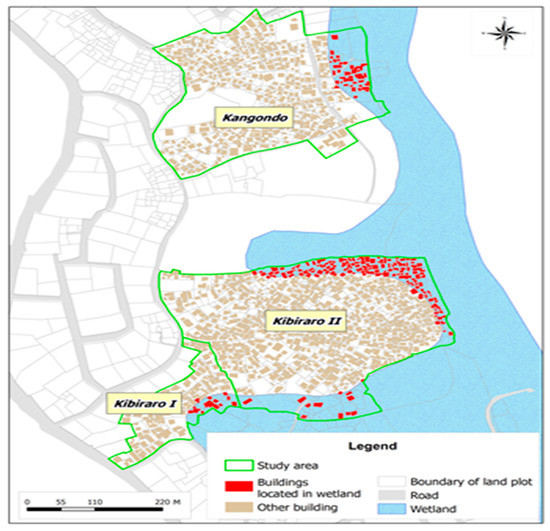

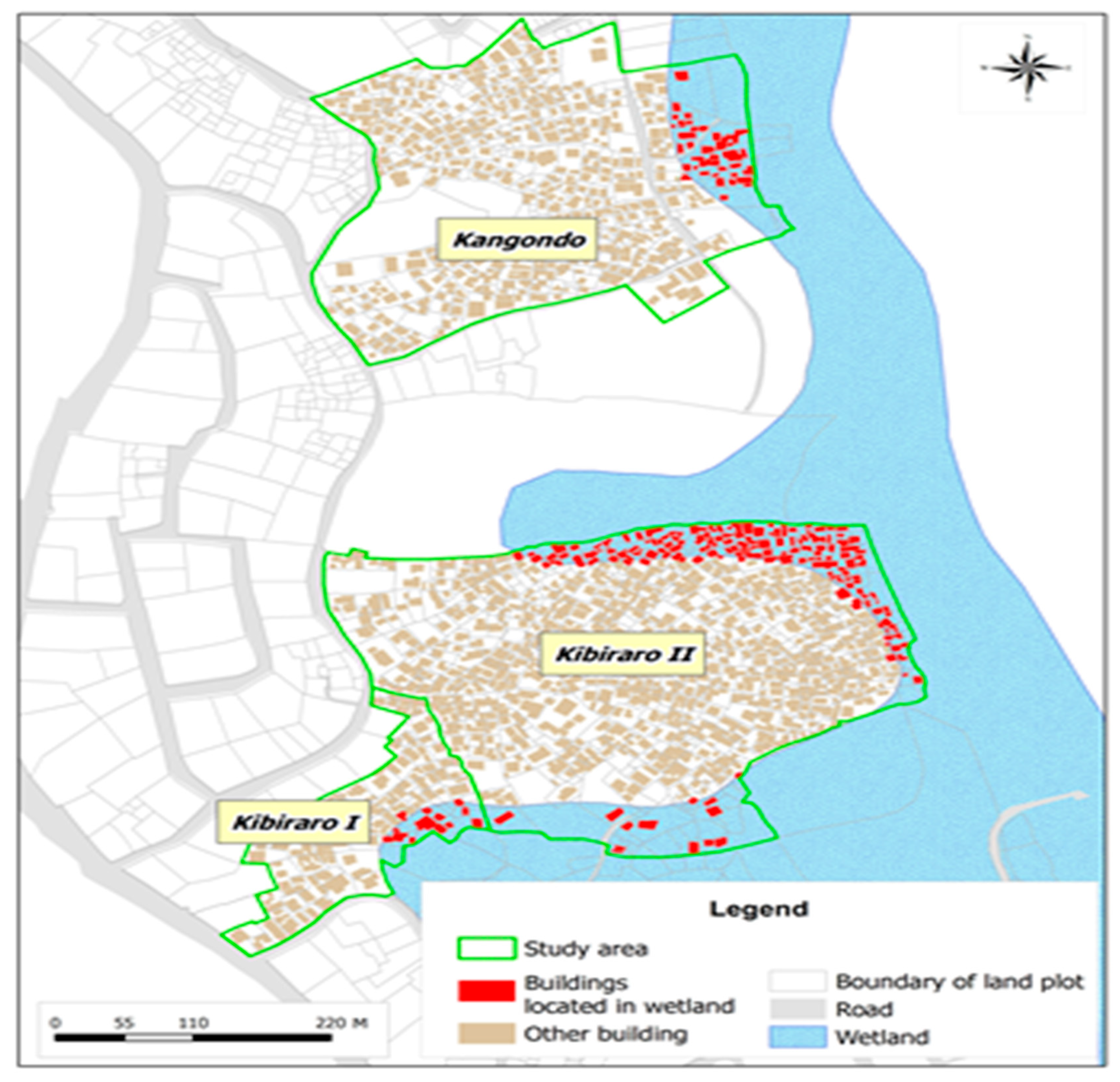

The study site is the informal settlement, comprising three neighbourhoods of Kangondo I & II and Kibiraro located in Nyarutarama cell, Remera sector, Gasabo district, Kigali city. It lies at 8 kilometres from the central business district (CBD) of Kigali city and 5 kilometres from the main national stadium located in Remera zone, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Location of the study area; data source: field survey (January–March of 2018 and January to February of 2019).

As previously mentioned, the expropriation of real properties in this site was carried out following Kigali city authorities’ decision to resettle expropriated property owners in a serviced residential neighbourhood for three reasons: to promote inclusive urban (re)development; to tackle the problems of limited access to decent houses for expropriated property owners; and to curb the proliferation of informal settlements, which is among the adverse effects associated with in-cash compensation [4]. In addition, this site represents the first experiment of relocation from single-family houses to a shared flat for the resettled property owners. Therefore, it was purposefully selected to assess how well and in what ways the resettlement as a form of compensation for expropriation can achieve spatial justice.

The development of informal settlements in the study area was prominent between 2000 and 2008, owing to the rapid growth of Kigali city inhabitants (accelerated by poor and low-income rural-urban migrants in search of employment in the closest planned residential neighbourhoods), poor physical planning, and low enforcement of housing development regulations during that period [52]. The three neighbourhoods of Kangondo I & II and Kibiraro thus evolved into overcrowded and non-organised settlements deprived of some urban amenities such as sanitation systems, waste disposal, and roads. In the framework of the current re-development processes of Kigali city, these sites have been identified among informal neighbourhoods that will be transformed into modern villas [52]. Before clearing these neighbourhoods, property owners will be resettled in another site called Busanza (as shown on Figure 2), as a form of compensation.

5.2. Sampling

We randomly sampled 306 respondents out of 1498 households, including 84 squatters who do not hold formal land rights. This sample size was determined using the following formula, applied in selecting the sample from the finite population and seeking a generally acceptable level of confidence and standard error [53]:

where

- Z = is the value assigned for the confidence level of 95%, with 1.96 as a confidence level score;

- p = the desired proportion for the sample size n, which is 0.5;

- e = the marginal error (10% in this study);

- N = population size (for the whole study area).

As the study area is divided into three neighbourhoods, we distributed our sample proportionally to the number of households recorded in each neighbourhood as follows: 126 respondents in Kangongo I, 108 in Kangondo II, and 72 in Kibiraro. By distributing these selected samples over the total number of households in the respective neighbourhoods, we realised that one person out of five could participate in the survey. We, therefore, skipped four to five households in each neighbourhood to survey the next one and so on, in order to cover the whole geographic area.

5.3. Primary and Secondary Data Collection

Primary data were collected through household surveys and in-depth semi-structured interviews with expropriated property owners, as well as structured interviews with 27 people, comprising of decision makers and other professionals from public and private agencies involved in the resettlement process. We also interviewed eight researchers in higher education and research institutions who have published on the topics related to urban (re)development and expropriation in Kigali. Survey questions used a Likert scale with five levels of scores to evaluate whether rules guiding the resettlement of expropriated property owners and their implementation processes abide by the aspirations of the four forms of spatial justice. The five levels of the Likert scale and related scores were defined as very unjust (with 1 score), unjust (2 scores), neither unjust nor just (3 scores), just (4 scores), and very just (5 scores).

Another measurement approach, following from our evaluative framework in Table 2, consists of the percentages of expropriated property owners participating in expropriation and resettlement who reported that their resettlement is likely to result in just outcomes. These percentages were aligned with the Likert scale scores to harmonise the presentation of the results. In that framework, rules are perceived as just if they recognise the basic rights and needs of expropriated property owners. Their implementation processes are just if they are fairly applied by actors in expropriation and resettlement, in partnership with property owners to come up with just outcomes [17]. Just outcomes consist of access to other real properties of similar or higher market values, including decent houses that fit the sizes of the resettled households and restoration of their livelihoods.

The survey was carried out during the pre-resettlement period. Expropriated property owners were already informed about their resettlement process, and had visited the new houses that they would receive as a form of compensation [8]. Through the household survey and interviews, we collected primary data on the following topics: household characteristics (including the size, the source of incomes, employment status), property owners’ appreciation of the compensation option and their resettlement processes, their roles in these processes, the market value and housing conditions in the existing and new settlement sites, opportunities and challenges associated with their resettlement, and livelihood conditions (including working opportunities and income generating activities) before and after resettlement. Some data related to these topics were collected through field observations in these sites.

Secondary data were collected through the review of the expropriation law, research papers, and reports on expropriation in Kigali city, and valuation reports held by either expropriated property owners or real property valuers who participated in real property valuation. Data on the market values of expropriated and new houses were compiled through review of the valuation reports and the resettlement plans for expropriated property owners. The master plans and various regulations and policies related to Kigali city (re)development were also reviewed. During this document review, attention was paid to the compensation options applicable in the expropriation of the real property (such as land and houses), decision making on the compensation option, and planning and implementation of resettlement of expropriated property owners. Aspects related to participation and collaboration between property owners and government officials implementing the expropriation law and Kigali city (re)development schemes were also investigated. As the expropriation and resettlement processes of expropriated property owners in Kigali city have largely attracted the attention of the local media during the last five years, the related records including video (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xiFZfvO9YzY) and online newspaper articles (see, for instance, https://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/227839, https://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/219817, and https://www.reuters.com/article/us-rwanda-landrights-housing/controversial-slum-relocation-kicks-off-in-rwandas-capital-idUSKBN1HJ39Z) were accessed and reviewed. This study is limited to the main aspects of spatial justice, including collaboration between the property owners and the expropriating agencies, restitution of access to housing and basic amenities, and socio-economic livelihoods of expropriated property owners alongside their resettlement processes. It does not analyse the processes of determining the compensation value and related challenges, which were analysed in another paper, previously published by Uwayezu and de Vries [4].

5.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis relied on the transcription of recorded information from the interviews and household surveys. Transcripts were organised into eight themes, corresponding to the spatial justice variables that are under evaluation, as presented in Table 2. As the evaluation uses the measurement scale with five levels, the recorded scores and other quantitative data were organised in table format using Excel. The Mann–Whitney statistical analysis test was used to assess significant differences between the scores recorded for evaluative indicators and variables of spatial justice (for the rules, processes, and outcomes), with respect to the appreciations of respondents to the related survey questions. These scores are presented in Table 3 and discussed in combination with our general findings in the following section.

Table 3.

Patterns of spatial justice in rules, processes, and outcomes of the in-kind compensation in Kigali city. Data source: review of rules related to expropriation and Kigali city (re)development, and analysis of field data (collected from January to March 2018, and January to February 2019).

6. Results and Discussion

In this section, we present our results on the assessment of whether aspirations of spatial justice are met during the resettlement of expropriated property owners in Kigali city. After the presentation of results, we suggest different approaches through which these aspirations can be effectively attained, based on features of spatial injustices identified in the implementation of this form of compensation.

6.1. Patterns of Spatial (In)Justice Emerging from the In-Kind Compensation in Kigali City

Various aspects of spatial (in)justice identified in the rules and processes underlying the implementation of the in-kind compensation for expropriated property owners in Kangondo and Kibiraro are presented in this section. The recorded scores on survey-based variables and related forms of spatial justice are presented in Table 3 and discussed subsequently. Generally, they show that spatial justice aspirations are very well met at the rules dimension, with scores ranging between 4.6 and 4.8 out of 5 for procedural, recognitional, redistributive, and intra-generational justice. Scores of 4 and 5 indicate that rules governing resettlement are “just” and “very just”, respectively [17]. This means that the expropriation law and various rules related to Kigali city (re)development incorporate different provisions that are aligned with general aspirations of spatial justice. However, the scores for the processes and outcomes dimensions are much lower (they generally oscillate between 1.0 and 1.3 out of 5) than the scores recorded at the rules dimension. These low scores indicate little likelihood to attain spatial justice aspirations at both the processes and outcomes dimensions. The non-compliance to the rules and lack of collaboration between government officials and expropriated property owners in the implementation of the expropriation law and related resettlement process are the main factors for these low scores. Nevertheless, very good scores were recorded for other variables at both the processes and outcomes dimensions. These variables comprise the market value and quality of developed houses and increased tenure security, as shown in Table 3 and discussed in the forthcoming sub-sections.

6.1.1. Forms of Spatial Justice Associated with the In-Kind Compensation for Expropriated Real Properties in Kigali City

In this section, we discuss evidences of spatial justice identified from the implementation of the in-kind compensation for expropriated property owners in Kigali city. These evidences embrace the market value and quality of developed houses, and increased tenure security.

Compensation at the Market Value and Improved Quality of Housing Exhibit Various Patterns of Spatial Justice

The assessment of the market value and quality of housing units developed for expropriated property owners reveals scores of 4.8 at the rules dimension and 4.7 at both the processes and outcomes dimensions, out of 5. These scores are linked with recognitional and procedural justice attained through compliance with the expropriation law stipulating that the compensation for expropriated real properties should not be below their market value [20]. This is also reiterated in the international norms related to fair compensation [40,42]. Our results show that the pursuit of this spatial justice aspiration resulted in increased market values for the new houses that are disproportionately very high if compared with the values of expropriated houses in the pre-relocation settlement (for all income categories), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Market values of in-kind compensation compared with the values of expropriated properties. Data source: household survey (January–February 2018) and expropriation rolls.

The high market values of the new houses also exhibit some aspects of redistributive and inter-generational justice attained through the allocation of more financial resources in the resettlement of expropriated property owners in order to promote their access to decent housing, especially for the poor households, as stated by our key informants. The poor households (category 1) whose houses in the pre-relocation settlement are in poor quality (because they were developed using local, low-cost, and non-durable materials such as mud bricks and used iron sheets) receive the greatest values (298% higher than expropriated houses) in the shares of new houses’ prices. Their high market values are associated with construction materials, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Housing conditions in Kangondo and Kibiraro. Data sources: Rwanda Housing Authority [52] and field survey (January–March 2018 and January–February 2019).

Table 5 shows poor housing conditions that exist in pre-resettlement neighborhoods. Most of the houses are old and should be renovated. However, the renewal process has not been possible as Kigali city zoning regulations ban this process in informal settlements, except for simple painting or minor reparation [54]. The precarious conditions of these houses are associated with a high poverty rate of 40% among their owners. Yet, some of these houses have annexes that owners rent to tenants or for small retail activities to generate income. By comparing their quality and that of the apartments developed in the relocation site, there is a significant difference between them, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Housing aspects before and after the resettlement. Data source: field survey (January–March 2018, January–February 2019, and June 2019).

Figure 3 shows that the quality of expropriated houses is much lower than that of apartments developed for expropriated property owners. In fact, the fieldwork for this study was carried out when the construction of the new houses was 70% complete. Some of these houses already had installations for pipe water, electricity, and drainage systems. They are also close to basic urban facilities such as schools and health centres. Each house contains a bathroom, an internal toilet, and a kitchen, which do not exist in some households in the pre-relocation settlements, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Access to basic amenities before and after resettlement. Data source: field survey (January–March 2018, and January–February and June 2019).

Table 6 shows the percentages of expropriated property owners with basic urban amenities and services available on the premises or distances from the neighbourhood and how their resettlement increases their access to these amenities and services. This increase is featured in procedural justice, in tandem with recognitional and redistributive justice, whose aspirations embrace the increased access to basic urban amenities and services for the resettled people. Related variables culminate to a mean score of 4.8 out of 5 at the rules, processes, and outcomes dimensions, as shown in Table 3. Indicators of recognitional and redistributive justice include the formal recognition of the rights of all of these people to housing, and the integration of their settlement in the formal planning processes as reiterated in the national and international guidelines for the inclusive urban (re)development [10,29], from which the security of tenure may emerge [55]. In the following section, we explore how the compliance with these guidelines can enhance tenure security, in relation to specific forms of spatial justice identified in the resettlement process of property owners in Kangondo and Kibiraro.

Compensation for All Tenure Types and Increased Tenure Security through Various Forms of Spatial Justice

The resettlement of expropriated property owners in Kangondo and Kibiraro has also been perceived as a driver for tenure security, especially for poor squatters. Apart from the formal resettlement, this security of tenure is also connected to the claim of procedural, recognitional, and intra-generational justice in relation to the payment of compensation for all displaced property owners, in all forms of land tenure [17]. In our case study, most of the poor had informally acquired their land by encroaching the wetland (which is public land), where they illegally developed their houses. The study identified 84 houses (in red colour) and 107 land plots occupied by squatters and located within this wetland, as shown in Figure A3. Despite the illegality of these houses, their owners receive an in-kind compensation as well as those who developed their houses on legally owned land plots. According to the 2005 law determining the modalities of protection, conservation, and promotion of environment in Rwanda, the development of residential or commercial buildings in wetlands is prohibited [56]. Article 19 of the Rwandan land law places wetlands in the public domain on which individuals cannot enjoy perpetual use rights [50]. In this respect, the master plan of Kigali city recommends the removal of all residential or commercial buildings from the wetlands. The provisions of these legal instruments on the illegality of houses located in wetlands have caused a high degree of tenure insecurity for squatters in these areas, which resulted in increased fear of eviction (household survey (January–February 2019)).

Regardless of the illegal status of these houses, their values were determined during the process of expropriation, so that their owners will be compensated. The compensation is embedded in the recognition of their rights to housing as stipulated in national policies and laws (mentioned in Section 3), which promote access to decent housing, basic amenities, and services for all Rwandans. These goals are consistent with the welfare-based principle of spatial justice appealing for the increased recognition of property rights for the most disadvantaged people, alongside the implementation of all urban space (re)development processes. In this respect, spatial justice scholars such as Soja [38] and Rawls (1999, pp. 5–6) [31] suggest the application of specific resource allocation arrangements (devised without compliance to the formal law) in order to improve the living conditions of these people. Thus, the pursuit of spatial justice towards improving the conditions of poor people may imply the non-compliance to the principle of rule of law, from the perspective of the legal law enforcement [57].

During the resettlement process of expropriated property owners in Kigali city, decision makers have been conscious that eviction of illegal settlers can harm their livelihoods and deteriorate their socio-economic conditions. Those impacts are mitigated through resettlement of this category of urban dwellers. Throughout our interviews, decision-makers, local authorities, and urban planners acknowledged awareness of the housing rights of poor urban dwellers. These key informants pointed out that the ongoing resettlement processes for expropriated property owners has been adopted in a bid to promote the integration of all categories of Kigali city inhabitants in the urban fabric. Therefore, the resettlement processes embrace various patterns of procedural, recognitional, redistributive, and intra-generational justice, if we link them to the provisions of urban development policies that guide the relocation of the displaced urban dwellers. Procedural and recognitional justice is embedded in the land and urban housing policies of Rwanda and the NST1, which state that the displaced informal settlers should be relocated to prevent their deprivation of access to housing [11,58]. On this note, our key informants stated that they abide by the conviviality pillar of the national urbanisation policy. This pillar claims for the promotion of urban quality of life and social inclusion [10], so that compensation of informal settlers through their relocation in planned sites is accordingly carried out.

As for other forms of spatial justice, redistributive and intra-generational justice are embedded in the equality of rights and opportunities in access to basic urban amenities and services for expropriated property owners and allocation of decent houses to those who have been living in wetlands. These aspects of spatial justice are substantiated by the results of our household survey. In Table 3, they show a mean score of 4.8 out of 5 at three dimensions of spatial justice and the aspect related to the compensation for all tenure types. Generally, if the laws prohibiting housing development in wetlands were respected and strictly implemented, squatters who developed their houses on these lands should not receive any compensation, as stated by our key informants. These squatters could have been evicted without relocation. However, the increased consideration of spatial justice aspects in the current expropriation processes has resulted in the recognition of their rights to housing (by decision makers and political leaders) through their resettlement. Still, the housing ownership aspect received medium scores for the processes and outcomes dimensions, because the expropriated property owners have not moved in new houses and thus do not have ownership documents. Yet, their resettlement to a site planned for housing development is arranged, so that they will not feel any risk of eviction, as reported by 96% of participants in our survey whose houses are located in wetlands. The decreased likelihood of eviction and their integration in the urban space (this aspect records a score of 4.8 out of 5 at the rules, processes, and outcomes dimensions, as shown in Table 3) are also driving factors for the perceived tenure security. To stress this, one of the respondents to the survey questionnaire, stated the following:

“One of the benefits for my resettlement is the access to quality housing in a planned neighbourhood. I will no longer feel any risk of eviction since it is the government that decided about this resettlement”.

Despite these good outcomes, there are other aspects of spatial justice that show very low scores and tend to depict some patterns of spatial injustices in the implementation of the in-kind compensation.

6.1.2. Limited Evidence of Spatial Justice in the Implementation Processes and Outcomes of the In-Kind Compensation

In this sub-section, we discuss the general problems identified during implementation processes of in-kind compensation and their implications on the livelihoods of expropriated property owners. These problems are linked with the unwillingness of expropriating agencies to negotiate with property owners on the compensation option and include them in the planning and implementation of resettlement processes. This resulted in the non-recognition of the basic needs and rights to employment and/or income-generating activities of these property owners, which can be well comprehended from a spatial justice lens.

Lack of Negotiation on the Compensation Options and Community Participation in the Resettlement Processes: Deficient Procedural and Recognitional Justice

Procedural and recognitional justice considerations contribute to fair negotiation with real property owners during the expropriation projects and their participation in urban space (re)development, which are a prerequisite to attaining just outcomes [17,32,59]. Negotiation on compensation options and participation of expropriated people in their resettlement are their rights and factors for procedural and recognitional justice. These aspects of spatial justice should be embedded in the rules and processes of urban (re)development to reach fair and transparent decision and outcomes [17]. The related forms of spatial justice received a score of 4.6 out of 5 for the rules dimension (as shown in Table 3). This finding is consistent with the Rwandan expropriation law, which recognises the rights of property owners to negotiate on the compensation option, even though it does not entitle these people to participate in the planning and implementation of their resettlement process. Nevertheless, different policies and regulations related to urban (re)development such as the urbanisation policy, national human settlement and housing policies, and laws related to land use planning and building development in Rwanda entitle the local community the rights to be engaged in all processes related to the design and implementation of urban (re)development plans [49,60,61,62,63].

However, there is criticism that these rights are not respected [2,22]. Representatives of Kigali city and local government entities (like the districts and local leaders) are the main actors who implement the master and detailed plans of Kigali city, designed from 2008 to 2013 by independent consultancy firms without local community engagement [51]. This practice has resulted in a top-down urban planning approach, which does not open the room for local community participation in urban space management. Yet, members of the sector and district councils represent the local community in making decisions related to local development, including the establishment of local development plans [64]. However, this approach of Kigali city management was criticised by participants in our household survey who stated that their representatives do not advocate for their needs and rights during the approval of these local development plans. One of them argued the following:

“The members of the sector and district councils may not have power to influence the high-level decision makers who are responsible for the implementation of Kigali city master plan. They are informed about what has been planned and requested to communicate the information to the local community in the sake of compliance (Summary of property owners’ arguments, compiled during the household survey.)”.

The lack of communicative and participatory urban planning is shown by the deficiency of the spatial justice frames related to negotiation and participation in the implementation processes of the expropriation in Kigali city. As shown in Table 3, these spatial justice aspects received mean scores of 1.3 and 1.0 out of 5, as recorded during the household survey. The non-recognition of property owners’ rights to negotiate the compensation options or participate in the valuation process is frequent in developing countries, such as Angola, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Nigeria, Thailand, and Zimbabwe. This happens when the expropriating agencies face a shortage of budgets and under-estimate the compensation in order to lower the cost of expropriation [65,66]. Although there is no evidence for this practice in Kigali city, government officials implementing the master plan of this city do not clearly justify the reason for not negotiating with the property owners on the compensation option. They argue that negotiation and participation of property owners in expropriation, design, and implementation of their resettlement plans may be cumbersome and time-consuming because their expectations diverge from those of decision makers [4]. During our interviews, one of these officials implementing the expropriation process stated the following:

“Property owners do not like to negotiate. They prefer to be compensated in a monetary form. Unfortunately, this compensation option does not help all of them to access new properties in Kigali city. They move towards the urban fringe where they informally develop new houses. This practice has to be discouraged. For the government as well as property owners, the best option which can promote their access to quality housing, basic urban amenities and their integration in the urban space is the resettlement (Interviews with local leaders, Kigali city authorities)”.

Despite this justification for not negotiating and collaborating with property owners in the expropriation process, these authorities do not provide any evidence about a failed attempt to use this approach. Nevertheless, negotiation and collaboration approaches have been applied without compromising the success of expropriation and resettlement projects in various countries such as Morocco, India, Sri Lanka, East Timor, and Pacific States [67,68,69,70]. In Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Slovenia, and Germany, the expropriation process and the determination of compensation value for private real property involve negotiation and agreement between the property owners and the expropriating agencies [67,71,72].

The lack of compliance with these ethical frames during expropriation and resettlement of affected property owners in Kigali city has resulted in the construction of houses that do not fit the sizes of their families. An immediate consequence is overcrowded houses (like the studios) for 63% of expropriated households. This reveals the low level of compliance to spatial justice criteria in all its forms and dimensions, as shown by a moderate score of 3.1 at the rules dimension, which falls to 1.1 out of 5 for the processes and outcomes dimensions (see Table 3). The scores ranging between 1 and 2 indicate the lack of spatial justice aspects in rules and processes related to the resettlement of expropriated households, and the factor for developing small sized houses, which do not fit the number of people in each household. Another factor is the limited financial capacity of the expropriating agencies to develop big houses for these property owners, although the market values for these small houses are still higher than the values of expropriated properties. This aspect is discussed in detail in the next sub-section.

Fair Compensation at Market Values Is Not Always Spatially Just

As stated in Section (Compensation at the Market Value and Improved Quality of Housing Exhibit Various Patterns of Spatial Justice) and shown in Table 4, the in-kind compensation for expropriated property owners results in developing modern houses for which market values are higher than the values of expropriated properties. However, these high market values are not commensurate with the adequate housing, which is the basis for good housing conditions for the resettled people. An adequate housing unit is associated with its use-value. From a recognitional justice dialectic, access to a new house reflects just outcomes if this house can be used to meet the needs of the owners [73]. In contrast, the provision of a housing unit that does not consider the household size reflects a deficiency in recognitional justice. This results in overcrowding conditions that will be observed in the developed houses, in relation to their sizes and number of rooms, which do not match the sizes of expropriated households. During our survey, some of these households critically questioned the number of bedrooms and overcrowding aspect of these new houses they are supposed to receive as compensation, as follows:

“How can parents who have two or three children sleep in one-bedroom with their children? Each family should receive at least a house with different sleeping rooms for parents and children”.

Other people stated that their resettlement in apartments is not a good option, if they take into account the mean household size in Rwanda, which is close to five persons [74]. One of the expropriated property owners who will receive a studio (as a compensation) mentioned the difficulties associated with its uses, as follows:

“Tell me (he asked me) how can parents and their children sleep together in a studio? Decision makers are aware that parents do not sleep with children who are over 3 years old. Our relocation in the studio is even disrespectful to parents since sleeping in the studio will unveil our private relationships to children”.

Although existing houses in the pre-relocation settlements are very small (between 26 and 42 square meters), 58% of households live in at least two bedrooms for the parents and children. Among the 18% poor households, each of them has one bedroom occupied by the parents and a sitting room that is also used as a bedroom for the children, as revealed by our field survey data, presented in Table 4. In this regard, one of the expropriated women who participated in our survey stated the following:

“the expropriating agencies should bear the cost of a housing unit which can fit the size of each family if they really want to improve its living conditions”.

She went on and argued the following:

“If these agencies do not have such capacity, the compensation should be in monetary form so that we can move to other areas and develop other houses at our convenience”.

The arguments of these respondents concur with the general aspiration of spatial justice or international norms, which claim that expropriating agencies should pay enough to place expropriated people in the same or improved living conditions [40,42,44,45].

Generally, the consideration of procedural and recognitional justice aspects from the resettlement of expropriated property owners in Kigali city in relation to the overcrowding aspect of the houses they are supposed to receive leads us to posit that this compensation option is not spatially just. The lack of spatial justice is reflected in the non-participation of these property owners in the planning and implementation of their resettlement processes. This resulted in the development of new houses that do not fit their household sizes. This problem was discussed with one of the decision makers during our interviews. His responses were contentious, as he argued that, “the expropriated property owners whose family sizes do not fit within the developed houses have rights to rent or sell them to small or single families which can fit well in these houses”.

His argument contrasts with the urban development goals related to social inclusion and informal settlements growth mitigation in Kigali city [9]. If expropriated property owners sell the new houses that they are supposed to receive, they may relocate themselves in the informal settlements and contribute to their spatial growth, which is already mushrooming and no longer tolerated by the current Kigali city zoning regulations [27]. In addition, if they do not occupy the new houses in the resettlement site, this can result in their disintegration from the formal city and deprivation of access to basic urban amenities that the adopted in-kind compensation intends to tackle.

Risks of Income Losses: Deficiencies in Procedural, Recognitional, and Redistributive Justice

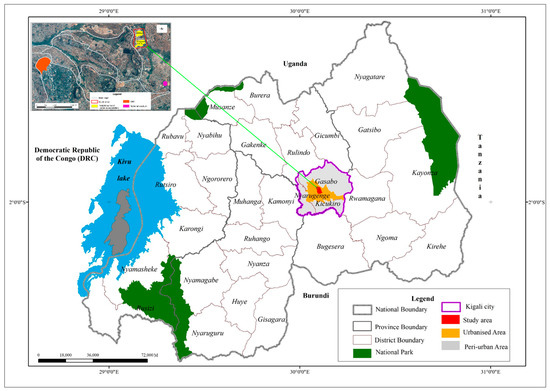

The implementation of the in-kind compensation for expropriated property owners in Kigali city also portrays deficiencies in procedural, recognitional, and redistributive justice with regards to the variables related to the access to jobs or employment opportunities. These variables received scores of 4.8 out of 5 at the rules dimension, which fall to 1.1 for the processes and outcomes, as shown in Table 3. Deficiency in procedural justice is associated with their displacement and resettlement in a site that is very far from their usual working places, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Working places for the inhabitants of Kibiraro and Kandongo. Data source: field survey (January–March 2018 and January–February 2019).

Figure 4 shows the working areas and sectors of employment for the inhabitants of Kangondo and Kibiraro sites. Among them, 30% are employed in masonry, garden, and security services. Artisanal workers represent 4%. People who are self-employed in business (such as trading and transport) are estimated at 35%, while those who are employed in similar businesses such as hotels, supermarkets, and bars represent 10%. Public servants (including teachers, nurses, and other government employees) represent 3%. The remaining (18%) are unemployed, but some of them rely on small incomes generated from renting the annexes of their main houses to low-income tenants. With respect to their current working places, the displacement of all these people will negatively affect their economic status and incomes. During our household survey, the self-employed people (like small retailers) expressed concerns about the loss of their businesses because the resettlement does not include in-cash compensation that could help them invest in new businesses in the new neighbourhood. In addition, these people will bear the high cost of their relocation and new equipment if they try to restart these businesses. One of them suggested the following:

“if the resettlement is the agreed upon option for compensation, decision makers should pay special consideration to the sources of our incomes so that our resettlement can be combined with financial compensation that we can use to restart our businesses”.

Notwithstanding this claim, other people are sceptical about the success of new businesses in the new location, because they will lose the customers with whom they have tied relationships (within and around their residential neighbourhoods). In addition, they mentioned the disruption of social networks that they have consolidated in these neighbourhoods. Economic hardship was also pointed out by people who are formally or informally employed by public and private agencies. The main problem is the loss of jobs and savings. Currently, these employees walk to their working places and back home. If they decide to keep their jobs after the resettlement, the mean commute distance will be 18 kilometres and 800 meters using public transport. However, their low salaries will not allow them to save a part of their income. The average monthly income of the heads of households varies depending on the type of employment or sources of their incomes. The monthly income ranges between 70.00 and 94.00 U.S. dollars for 28% of the heads of households; 94.00 and 118.00 for 20%; 118.00 and 176.00 for 20%; 176.00 and 235.00 for 15%; 235.00 and 294.00 for 10%; and 294.00 and 353.00 for 5%. It is above 353.00 U.S. dollars for only 2% (data source: field survey, January–February 2019 and Rwanda Housing Authority, 2017). This study assessed how transport-related expenses might affect these incomes if these people decide to keep their current jobs. The likely costs are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Cost for daily transport before and after the resettlement. Data source: field survey (January and February 2019) and review of data on local transportation tariff.

After their resettlement, the daily cost of transport will increase for people who currently use public transport to go to work, as shown in Table 7. This cost will also be high for others who currently walk to working places if they decide to keep their jobs and use public transport to reach their respective working places. This implies that each person may spend between 26.00 to 29.00 U.S. dollars per month if we count only the weekdays. Thus, the remainder of their net incomes will decrease. This will seriously affect 48% of people whose monthly income is less than 118.00 U.S. dollars. As these people already live under the poverty line [52], the resettlement will deteriorate their living conditions, as pointed out during our survey—they perceive high risks for impoverishment, if they keep their jobs (owing to the high cost of transportation), or limited opportunities for finding new jobs in and around their resettlement site, which is a new residential neighbourhood with very limited working opportunities.

In addition, the resettlement plan does not include any option for the creation of jobs or income-generating activities in this new residential neighbourhood. The risk of impoverishment is also perceived by 32% of landlords who earn their incomes from renting their secondary houses or annexes to main houses. Their resettlement will evidently result in the loss of this income source because each household will receive one family apartment (within the shared flats) as a form of compensation. During our survey, 17% of heads of households reported that they have already been enduring these economic losses from December 2018 (when they were informed about their resettlement in another area) because their tenants moved out in search of other houses in other neighbourhoods.

Another problem associated with the resettlement of these people is the cost of kitchen appliances (such as stoves, gas cookers, and cylinders) in the new houses, especially for these poor and very low-income groups. Some of them stated that they have been using charcoal or firewood for cooking in their pre-resettlement homes. However, it is not possible to use these sources of energy in shared flats, where the use of gas for cooking is required. The cost of these kitchen appliances is a financial burden that these people are not prepared to bear. They suggested that the expropriating agencies should bear this cost when compensation consists of resettlement in the apartments. The loss of the sources of incomes and other problems associated with the resettlement of expropriated property owners in Kigali city are similarly echoed in other studies on the processes of forced displacement conducted under the pretext of expropriation for public interest in various countries [41]. Disruption in socio-economic livelihoods and associated risks for impoverishment have been reported among the features of spatial injustices resulting from the expropriation processes carried out without compliance to the principles of equity and respect of the fundamental human rights in China, South Korea [75,76], Ethiopia [23], and Tanzania [77], among others. However, there exist different options that can be applied to decrease these spatial injustices. Some of these options are discussed in the next section.

6.2. Options for Promoting Spatial Justice in the Implementation of In-Kind Compensation in Kigali City

In this section, we present and discuss three main options (compatible with the demands of spatial justice) through which in-kind compensation can be implemented, as suggested by the heads of households who participated in this study. These options include the combination of in-cash compensation and self-help incremental housing development in another residential site; social mix and participatory in-situ resettlement; and resettlement in the urban village and diversified dwelling units around business and services areas. Some of these options are reiterated in the current rules and strategic development plans related to both urban and socio-economic development in Rwanda. Applying them during the resettlement of expropriated property owners may result in spatially just outcomes in the broad context of inclusive urban (re)development.

6.2.1. The In-Cash Compensation and Self-Help Incremental Housing Development: Procedural, Recognition, and Redistributive Justice

To cater for the problem associated with the habitability of housing units allocated to expropriated property owners in Kibiraro and Kangondo, a possible just option suggested by 96% of these people is the combination of the in-cash and in-kind compensation. It would consist of fair compensation in a monetary form for the houses and other developments on the land, and the provision of serviced land plots in another residential site that is close to employment opportunities such as commercial or industrial areas. As they stressed, the selection of this site should be carried out in a participatory manner, through collaboration between Kigali city authorities and property owners. Thereafter, expropriated people can incrementally develop their own houses, using the compensation paid for the non-movable properties. This option is commensurate with different forms of spatial justice such as procedural embedded in compensation at market value for these properties and engagement of property owners in developing their residential neighbourhood, following a participatory planning approach of their resettlement.

Recognitional and redistributive justice are reflected in recognition of the expropriated property owners’ rights to produce their dwelling units, which are compatible with their family sizes. Redistributive and intra-generational justice are exhibited in the allocation of residential land plots to these people so that they can develop (through self-help construction) diversified dwelling units, aligned with their needs and financial capacities [1,78]. However, finishing a self-help house may be difficult for the poor and very low-income categories. This can result in the transformation of the selected residential site into shacks or informal settlements. To minimise this risk, the implementation of the self-help housing development approach can be applied through a partnership of expropriated property owners with Kigali city authorities, urban planners, and other government officials who are engaged in the management of this city. Therefore, these actors can seek other forms of support (from local NGOs, international development agencies) that may consist of material or financial assistance to the poor and very low-income urban dwellers who may fail to develop the received land plots according to the proposed housing development plan. The financial support can also be provided by Kigali city and the central government, as reiterated in the NST1, and different strategic development plans of Rwanda [9]. In the case in which it is difficult to implement the self-help housing development in partnership with Kigali city authorities and their representatives owing to their limited time, at least the resettlement plan of expropriated households should be designed in a participatory manner. Thereafter, it can be implemented through regular control by local leaders and professionals at a low-level of government who enforce local community compliance with the master and local development plans of this city [2].

6.2.2. Promotion of the Social Mix through the Participatory In-Situ Resettlement

Social mix is among the options that can be applied to promote spatial justice with urban (re)development, through the integration of poor and low-income urban neighbourhoods and their inhabitants in the formal city [79]. The social mix approach is supported by 95% of households who participated in this study, as it can enhance their formal integration in the urban space. Its application can result in developing dwelling units that are balanced in the needs of all categories of urban dwellers. This housing development option, which is acclaimed to be spatially just, is largely echoed in the work of Arthurson, Levin, and Ziersch [80,81]. According to these scholars, the social mix is like a corridor for spatial justice flagship in the urban space (re)organisation when it consists of clearing and re-developing the declining poor and low-income neighbourhoods. One of its outcomes is the protection of these areas’ inhabitants against the displacement [82]. The social mix has been implemented in different ways. Its most common implementation practice has been termed the “organic mix”, consisting of developing mixed housing typologies that integrate various socio-economic groups in a spatially just and inclusive urban space [83]. As Marcuse, (2009, p. 190) contends, apart from advancing the equality in access to decent housing, the organic mix promotes access to basic urban amenities and services required for the welfare of all urbanites [84].

Although the existing literature shows that this urban (re)development option has mainly been implemented in developed countries such as The Netherlands [85,86], Australia [80,81], United Kingdom, USA, and Canada [87], it is among the options that can be applied to advance recognitional and redistributive spatial justice in Kigali city management. This option is reiterated in the urbanization policy [10], housing policy [11], and urban housing policy of Rwanda [88], as well as the master plans of Kigali city [51,89], whose goals include the integration of all categories of urban dwellers in the urban spaces through the development of mixed-income residential neighbourhoods. Its implementation requires a communicative and collaborative urban planning approach, embedded in procedural and recognitional justice, which allows for various categories of urban dwellers (poor, middle, and upper income groups) to interact and design urban (re)development plans for the creation of diversified residential neighbourhoods that permit their integration in the urban geography [17,30,90]. These residential neighbourhoods should be connected through a fair provision of public facilities in order to minimise the risks of spatial segregation [91].

If the organic mix approach is used for the in-situ resettlement of expropriated property owners, it prevents their displacement through the redevelopment of their neighbourhood, which can include the conversion of the existing single houses into low- and middle-rise apartments in order to optimise the use of suitable buildable land. In addition, it can preserve the social relations among these people and support their livelihood enhancement. We propose this urban (re)development approach in an attempt to mitigate various challenges such as the loss of employment opportunities that expropriated property owners may face after their off-site resettlement. In addition, this approach is among the informal settlement management options suggested by various studies on Kigali city [52]. Its implementation requires the landscape and environment management operations to minimise the environmental hazards [92]. However, construction works of new houses for the property owners in Kangondo and Kibiraro who participated in this study are almost finished. It is expected that these people will move into these houses by June 2020 (see https://www.ktpress.rw/2020/03/relocation-from-bannyahe-high-risk-zone-begins). Despite the current progress in their resettlement process, this study identified that it could have been possible to relocate these urban dwellers in one part of their neighbourhood, and thus reduce their displacement. Thus, the suggested social mix approach can be applied in further processes of expropriation and in-kind compensation in Kigali city.

6.2.3. Urban Village and Diversified Dwelling Units: Reframing Recognitional, Redistributive, and Intra-Generational Justice

Resettlement in urban villages can be another option for mitigating the problem of overcrowding associated with housing conditions of expropriated property owners in Kibiraro and Kangondo. As suggested by 73% of participants in our survey, an urban village can be developed in the neighbourhoods that are close to employment opportunities in order to increase the chances for the resettled households to improve their livelihoods. The village (some models are already under construction in Kigali city, as shown in Figure 5) can comprise various housing units whose number of bedrooms matches the sizes of expropriated households.

Figure 5.

Model of an urban village under construction in Kigali city. Data source: field survey (January–March 2018 and January–February 2019).

The urban villages shown in Figure 5 comprise various blocks of residential houses, connected to basic urban amenities and services. Each housing unit has one sitting room, two bedrooms, a toilet, a kitchen, a bathroom, and a food pantry. It costs around 5650.00 U.S. dollars. This type of housing unit can be more convenient for expropriated property owners than being resettled in a studio or a one-bedroom apartment. As the costs of the studio and one-bedroom apartment are estimated at 16,723.00 and 22,965.00 U.S. dollars respectively, it can be possible to use this money to develop a large dwelling unit, with three to four rooms, at a lower cost than that of one studio or apartment. Unfolding this option can result in developing residential neighbourhoods comprising large units of connected houses and high-rise apartments (as shown in Figure 5), which can accommodate households of lower, middle, and upper socio-economic groups in the same area. This suggestion is in agreement with the material aspect of spatial justice, which appeals for promoting diversity and a mixed urban community within one neighbourhood without socio-spatial segregation [31].

7. Conclusions

This study applied a series of indicators to probe various aspects of spatial justice from the implementation of in-kind compensation for expropriated properties in Kigali city. The findings reveal that the rules dimension embracing the expropriation law, policies, and regulations governing the Kigali city (re)development and resettlement process of expropriated property owners has great potential to promote spatial justice in its four forms. These findings are supported by high scores (between 4.6 and 4.8 out 5) of various spatial justice indicators, namely, negotiation on the compensation option; fair compensation of all property owners from both formal and informal tenure; participation in the resettlement process; decreased displacement or risks of eviction; access to income-generating opportunities, urban amenities, and services; and integration of expropriated property owners in the urban fabric. However, the related indicators at the processes dimension, which stands for the implementation of the rules, have very low scores (between 1.1 and 1.3 out 5). These scores are connected to the non-compliance to procedural, recognitional, and redistributive justice by government officials implementing these rules, through the non-recognition of the rights of expropriated property owners to negotiate the compensation option and participate in their relocation process, as well as their rights to jobs and income-generating opportunities. This results in outcomes that are generally unjust, because they directly depend on the processes dimension for which most of spatial justice indicators received very low scores. Notwithstanding these low scores, the resettlement of expropriated property owners exhibits some aspects of spatial justice at the outcomes dimension, such as the equality in access to urban amenities and services as well as new houses in the planned residential site, which affirms their integration in the urban space.