A Conceptual Analysis of Switching Costs: Implications for Fitness Centers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Analysis

3. Method

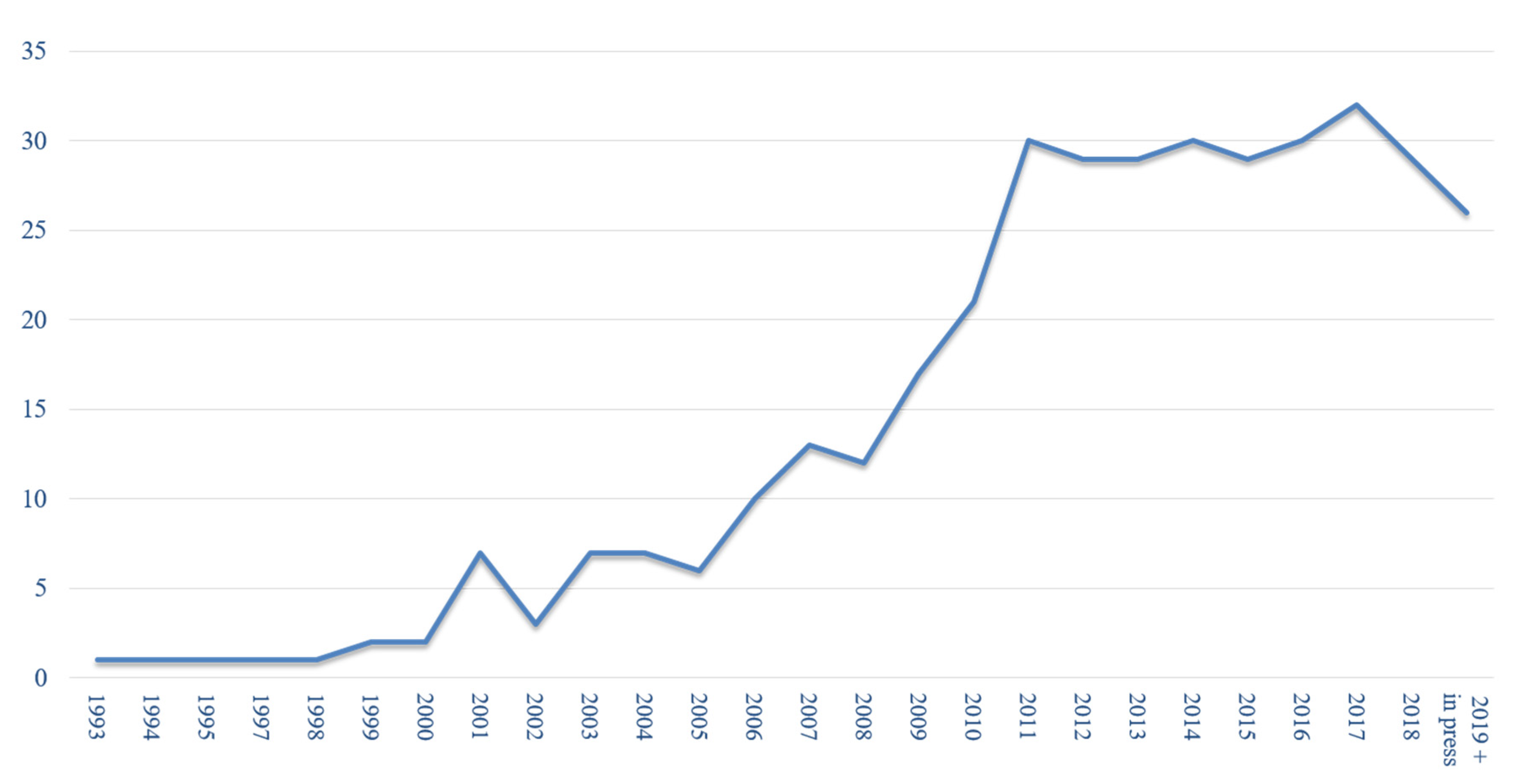

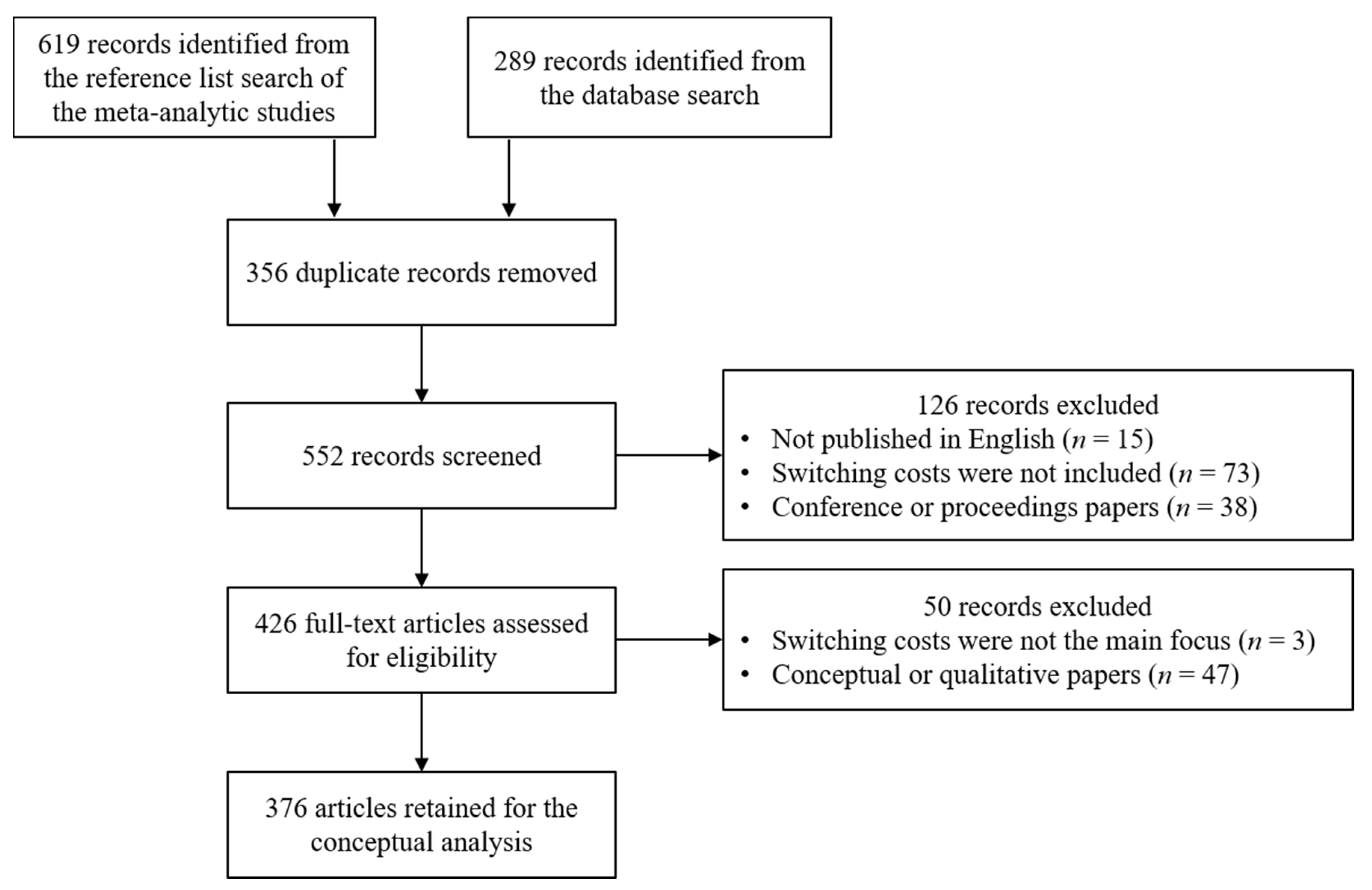

3.1. Article Identification

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Terminology

4.2. Definition

4.3. Dimensionality

4.4. Model Specification

4.5. Context

5. Contributions and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- International Health, Racquet and Sportsclub Association. The 2018 IHRSA Global Report; IHRSA: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Arroyo, M.J.; García-Fernández, J.; Gálvez-Ruiz, P.; Grimaldi-Puyana, M. Analyzing Consumer Loyalty through Service Experience and Service Convenience: Differences between Instructor Fitness Classes and Virtual Fitness Classes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, K.A.; Byon, K.K. A Mechanism of Mutually Beneficial Relationships between Employees and Consumers: A Dyadic Analysis of Employee–Consumer Interaction. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.A.; Byon, K.K. Examining Relationships among Consumer Participative Behavior, Employee Role Ambiguity, and Employee Citizenship Behavior: The Moderating Role of Employee Self-Efficacy. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2018, 18, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, R. What does the Research say about Member Retention in Fitness Centers? Available online: https://blog.mobilefit.com/research-member-retention-fitness-centers/#easy-footnote-bottom-1 (accessed on 27 December 2019).

- Turk, S. IBISWorld Industry Report 71394: Gym, Health & Fitness Clubs in the US; IBISWorld: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chuah, S.H.W.; Rauschnabel, P.A.; Marimuthu, M.; Thurasamy, R.; Nguyen, B. Why do Satisfied Customers Defect? A Closer Look at the Simultaneous Effects of Switching Barriers and Inducements on Customer Loyalty. J. Serv. Theory Pr. 2017, 27, 616–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.; Nguyen, B.; Mutum, D.S.; Mohd-Any, A.A. Constructing Online Switching Barriers: Examining the Effects of Switching Costs and Alternative Attractiveness on E-Store Loyalty in Online Pure-Play Retailers. Electron. Mark. 2016, 26, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piha, L.P.; Avlonitis, G.J. Customer Defection in Retail Banking: Attitudinal and Behavioural Consequences of Failed Service Quality. J. Serv. Theory Pr. 2015, 25, 304–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Beatty, S.E.; Evanschitzky, H.; Brock, C. The Impact of Service Characteristics on the Switching Costs–Customer Loyalty Link. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Beatty, S.E. Switching Barriers and Repurchase Intentions in Services. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Manstrly, D. Cross-Cultural Validation of Switching Costs: A Four-Country Assessment. Int. Mark. Rev. 2014, 31, 413–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Manstrly, D. Enhancing Customer Loyalty: Critical Switching Cost Factors. J. Serv. Manag. 2016, 27, 144–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klein, H.J.; Delery, J.E. Construct Clarity in Human Resource Management Review: Introduction to the Special Issue. Human Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, Y.; Brewster, C. Theorizing the Meaning (s) of ‘Expatriate’: Establishing Boundary Conditions for Business Expatriates. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 27–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barczak, G. Writing a Review Article. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2017, 34, 120–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tähtinen, J.; Havila, V. Conceptually Confused, but on a Field Level? A Method for Conceptual Analysis and its Application. Mark. Theory 2019, 19, 533–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, B.L. Concept analysis: An Evolutionary View. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications; Rodgers, B.L., Knafl, K.A., Eds.; W. B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Miragaia, D.A.M.; Constantino, M.S. Topics and Research Trends of Health Clubs Management: Will Innovation be Part of the Fitness Industry Research Interests? Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2019, 19, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Frennea, C.M.; Mittal, V.; Mothersbaugh, D.L. How Procedural, Financial and Relational Switching Costs Affect Customer Satisfaction, Repurchase Intentions, and Repurchase Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2015, 32, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pick, D.; Eisend, M. Buyers’ Perceived Switching Costs and Switching: A Meta-Analytic Assessment of Their Antecedents. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 42, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Beatty, S.E. Why Customers Stay: Measuring the Underlying Dimensions of Services Switching Costs and Managing their Differential Strategic Outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Zhong, Y.Y.; Tanford, S. Casino loyalty: The Influence of Loyalty Program, Switching Costs, and Trust. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 846–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, G. How Commitment both Enables and Undermines Marketing Relationships. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 1372–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R. Editor’s comments: Construct Clarity in Theories of Management and Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Zmud, R.W.; Sampson, J.P.; Reardon, R.C.; Lenz, J.G.; Byrd, T.A. Confounding Effects of Construct Overlap: An Example from IS User Satisfaction Theory. Inf. Technol. People 1994, 7, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, T.A.; Frels, J.K.; Mahajan, V. Consumer Switching Costs: A Typology, Antecedents, and Consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parganas, P.; Papadimitriou, D.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Theodoropoulos, A. Linking Sport Team Sponsorship to Perceived Switching Cost and Switching Intentions. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 17, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemes, M.D.; Gan, C.; Zhang, D. Customer Switching Behaviour in the Chinese Retail Banking Industry. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2010, 28, 519–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Recommendations for Creating Better Concept Definitions in the Organizational, Behavioral, and Social Sciences. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 19, 159–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, D.A.; Voss, K. A Proposed Procedure for Construct Definition in Marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Temerak, M.S. Examining the Impact of the Attractiveness of Alternatives on Customers’ Perceptions of Price Tolerance: Moderation and Mediation Analyses. J. Financial Serv. Mark. 2016, 21, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P. Construct Measurement and Validation Procedures in MIS and Behavioral Research: Integrating New and Existing Techniques. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 293–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. Construct Validity vs. Concept Validity. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2012, 22, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, R.; Collier, D. Measurement validity: A Shared Standard for Qualitative and Quantitative Research. Am. Politi Sci. Rev. 2001, 95, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, H.; Back, K.J.; Kim, Y.H. A Multidimensional Scale of Switching Barriers in the Full-Service Restaurant Industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2011, 52, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colgate, M.; Tong, V.T.U.; Lee, C.K.C.; Farley, J.U. Back from the Brink: Why Customers Stay. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 9, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G.; Reynolds, N.; Simintiras, A. Bases of E-Store Loyalty: Perceived Switching Barriers and Satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaweera, C.; Prabhu, J. The Influence of Satisfaction, Trust and Switching Barriers on Customer Retention in a Continuous Purchasing Setting. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2003, 14, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergel, M.; Brock, C. The Impact of Switching Costs on Customer Complaint Behavior and Service Recovery Evaluation. J. Serv. Theory Pr. 2018, 28, 458–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, C.; Picón, A. Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Perceived Switching Costs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Evanschitzky, H.; Backhaus, C.; Rudd, J.; Marck, M. Securing Business-to-Business Relationships: The Impact of Switching Costs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 52, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitten, D.; Wakefield, R.L. Measuring Switching Costs in IT Outsourcing Services. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.; Wright, R.; Thatcher, J.B.; Klein, R. Understanding Online Customers’ Ties to Merchants: The Moderating Influence of Trust on the Relationship between Switching Costs and E-Loyalty. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.L.; Xiong, L.; Chen, C.C.; Hu, C. Understanding Active Loyalty Behavior in Hotel Reward Programs through Customers’ Switching Costs and Perceived Program Value. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colgate, M.; Lang, B. Switching Barriers in Consumer Markets: An Investigation of the Financial Services Industry. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufteros, X.; Babbar, S.; Kaighobadi, M. A Paradigm for Examining Second-Order Factor Models Employing Structural Equation Modeling. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 120, 633–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Jarvis, C.B. The Problem of Measurement Model Misspecification in Behavioral and Organizational Research and Some Recommended Solutions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jarvis, C.B.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. A Critical Review of Construct Indicators and Measurement Model Misspecification in Marketing and Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two Structural Equation Models: LISREL and PLS applied to Consumer Exit-Voice Theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, J.R.; Bagozzi, R.P. On the Nature and Direction of Relationships between Constructs and Measures. Psychol. Methods 2000, 5, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.S.; Law, K.S.; Huang, G.H. On the Importance of Conducting Construct-Level Analysis for Multidimensional Constructs in Theory Development and Testing. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 744–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, Y.W.; Hsu, P.Y.; Huang, S.H.; Chen, J. Determinants of Switching Intention to Cloud Computing in Large Enterprises. Data Technol. Appl. 2020, 54, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwono, L.V.; Sihombing, S.O. Factors affecting Customer Loyalty of Fitness Centers: An Empirical Study. J. Din. Manaj. 2016, 7, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Kim, M.; Pifer, N.D. Importance of Theory in Quantitative Enquiry. In Routledge Handbook of Theory in Sport Management; Cunningham, G.B., Fink, J.S., Doherty, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, D.; O’Cass, A. Attributions of Service Switching: A Study of Consumers’ and Providers’ Perceptions of Child-Care Service Delivery. J. Serv. Mark. 2001, 15, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, M.; Smith, T. The Capability Approach as a Conceptual Bridge for Theory-Practice in Sport-for-Development. J. Global Sport Manag. in press. [CrossRef]

- Odio, M.A. The Role of Time in Building Sport Management Theory. J. Global Sport Manag. in press. [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A. “It takes a village:” Interdisciplinary Research for Sport Management. J. Sport Manag. 2013, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byon, K.K.; Zhang, J.J. Critical Statistical and Methodological Issues in Sport Management Research. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 23, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Term | Definition | Dimensionality | Specification | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ping (1993) | Switching costs | Self-made | Unidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Manufacturing |

| Jones et al. (2000) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Self-made | Unidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Financial services; technology, media, and telecommunication |

| Colgate and Lang (2001) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Others | Unidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Financial services |

| Jones et al. (2002) | Switching costs | Self-made | Multidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Financial services; personal service industry |

| Burnham et al. (2003) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Self-made | Multidimensional | 2nd-order not specified with 1st-order not specified | Financial services; technology, media, and telecommunication |

| Patterson and Smith (2003) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Self-made | Multidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Personal service industry; health care services; hospitality and tourism |

| Ranaweera and Prabhu (2003) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Bansal and Taylor (1999) | Unidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Technology, media, and telecommunication |

| Whitten and Wakefield (2006) | Switching costs | Self-made | Multidimensional | 2nd-order not specified with 1st-order not specified | Technology, media, and telecommunication |

| Balabanis et al. (2006) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Jones et al. (2000) | Multidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Retail |

| Jones et al. (2007) | Switching costs | Not reported | Multidimensional | 1st-order not specified | General service industry |

| Colgate et al. (2007) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Burnham et al. (2003) | Unidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Financial services; personal service industry; technology, media, and telecommunication; health care services; automotive industry; hospitality and tourism; sport industry |

| Han, Back, and Kim (2011) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Dick and Basu (1994); Ping (1993) | Unidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Hospitality and tourism |

| Barroso and Picón (2012) | Switching costs | Self-made | Multidimensional | 2nd-order formative with 1st-order reflective | Financial services |

| Blut et al. (2014) | Switching costs | Bendapudi and Berry, 1997 | Multidimensional | 2nd-order not specified with 1st-order not specified | General service industry |

| Carter et al. (2014) | Switching costs | Burnham et al. (2003) | Multidimensional: | 3rd-order formative with 2nd-order formative with 1st-order reflective | Retail |

| El-Manstrly (2014) | Switching costs | Burnham et al., (2003); Jones et al. (2007) | Multidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Financial services |

| Piha and Avlonitis (2015) | Switching costs | Not reported | Unidimensional | 1st-order reflective | Financial services |

| Xie et al. (2015) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Bendapudi and Berry (1997) | Multidimensional but aggregate construct | 1st-order not specified | Hospitality and tourism |

| El-Manstrly (2016) | Switching costs | Not reported | Multidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Personal service industry; hospitality and tourism |

| Temerak (2016) | Switching barriers | Jones et al. (2000) | Multidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Financial services |

| Ghazali et al. (2016) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Patterson and Smith (2003) | Multidimensional | 2nd-order not specified with 1st-order not specified | Retail |

| Blut et al. (2016) | Switching costs | Porter (1980); Others; Ping (1993) | Multidimensional | 2nd-order not specified with 1st-order not specified | Manufacturing |

| Chuah et al. (2017) | Switching costs | Others | Unidimensional | 1st-order reflective | Technology, media, and telecommunication |

| Parganas et al. (2017) | Switching costs | Not reported | Unidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Sport industry |

| Baloglu et al. (2017) | Interchangeable use between switching costs and switching barriers | Jones et al. (2000) | Unidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Hospitality and tourism |

| Bergel and Brock (2018) | Switching costs | Bendapudi and Berry (1997) | Multidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Financial services: personal service industry; transport and logistics |

| Chang et al. (2020) | Switching costs | Self-made | Unidimensional | 1st-order not specified | Technology, media, and telecommunication |

| Category | Frequency | Percentage | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminology | Specification | ||||

| Switching costs | 215 | 57.2 | 1st-order not specified | 327 | 87.0 |

| Switching barriers | 11 | 2.9 | 1st-order reflective | 28 | 7.4 |

| Switching costs and switching barriers | 146 | 38.8 | 1st-order formative | 2 | 0.5 |

| Termination costs | 2 | 0.5 | 2nd-order not specified | 11 | 2.9 |

| Switching costs and termination costs | 1 | 0.3 | 2nd-order formative with 1st-order reflective | 7 | 1.9 |

| Switching difficulties | 1 | 0.3 | 3rd-order formative with 2nd-order formative with 1st-order reflective | 1 | 0.3 |

| Definition | Context | ||||

| Porter (1980) | 41 | 9.4 | Financial services | 85 | 19.8 |

| Burnham et al. (2003) | 41 | 9.4 | Personal service industry | 16 | 3.7 |

| Jones et al. (2000) | 47 | 10.8 | Technology, media, and telecommunication | 139 | 32.4 |

| Heide and Weiss (1995) | 16 | 3.7 | Health care services | 20 | 4.7 |

| Dick & Basu (1994) | 15 | 3.5 | Automotive industry | 9 | 2.1 |

| Bendapudi and Berry (1997) | 14 | 3.2 | Hospitality and tourism | 42 | 9.8 |

| Ping (1993) | 6 | 1.4 | Retail | 64 | 14.9 |

| Jones et al. (2007) | 15 | 3.5 | Energy industry | 7 | 1.6 |

| Others a | 112 | 26.2 | Transport and logistics | 24 | 5.6 |

| Self-made | 33 | 7.6 | Sport industry | 3 | 0.7 |

| Not reported | 94 | 21.7 | Manufacturing | 1 | 0.2 |

| Dimensionality | General service industry | 15 | 3.5 | ||

| Unidimensional | 296 | 78.5 | Not reported | 5 | 1.2 |

| Multidimensional | 81 | 21.5 |

| Recommendations | Research Approaches in the Fitness Center Context. |

|---|---|

| 1: Future research in fitness centers should avoid an interchangeable use of the two terms of switching costs and switching barriers. |

|

| 2: Future research in fitness centers should (1) develop a definition of switching costs, (2) specify what costs mean, (3) avoid an interchangeable use of the two definitions of switching costs and switching barriers, and (4) use switching costs rather than switching barriers. |

|

| 3: Future research in fitness centers should (1) determine whether switching costs constitute unidimensional or multidimensional and (2) avoid modeling multidimensional constructs as a global construct. |

|

| 4. Future research in fitness centers should specify a switching costs measurement model. |

|

| 5. Future research in fitness centers should (1) identify context-specific dimensions, and (2) develop and validate a measurement for fitness centers. |

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, K.; Byon, K.K.; Choi, H. A Conceptual Analysis of Switching Costs: Implications for Fitness Centers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093891

Kim K, Byon KK, Choi H. A Conceptual Analysis of Switching Costs: Implications for Fitness Centers. Sustainability. 2020; 12(9):3891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093891

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Kyungyeol (Anthony), Kevin K. Byon, and Heedong Choi. 2020. "A Conceptual Analysis of Switching Costs: Implications for Fitness Centers" Sustainability 12, no. 9: 3891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093891