The Role of Public Participation for Determining Sustainability Indicators for Arctic Tourism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sustainable Tourism Indicators

3. Indicator Framework Development

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Key Work Components in the Framework

- (i)

- Selection of sustainability indicators based on a literature review on international standards and criteria;

- (ii)

- Selection of indicators that fit the area in question based on a compilation and reviewing of local literatures and reports with respect to sustainable development, as well as field observations of local condition;

- (iii)

- Public evaluation of the selected indicators’ applicability and priorities. The public is composed of local stakeholders related to each project;

- (iv)

- Experts’ evaluation of the indicators’ measurability and monitoring, as well as their causal relations;

- (v)

- An overall assessment of each indicator’s applicability for the area in question.

3.2.1. Selection of Key Indicators

3.2.2. Indicators Evaluation

3.3. Public Evaluation

3.4. Experts Evaluation

3.5. Each Indicator’s Overall Assessment

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Sustainability Indicators as a Tool for Managing Tourism Development in the Arctic

4.2. The Role of Public Participation for Determining Sustainability Tourism Indicators

4.3. Management Implication

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- UN (United Nations). Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations A/RES/70/1. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockström, J.; Öhman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Twining-Ward, L. Monitoring for a Sustainable Tourism Transition. The Challenge of Developing and Using Indicators; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Saarinen, J. Using indicators to assess sustainable tourism development: A review. Tour. Geogr. 2013, 16, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN (United Nations). The CSD Theme Indicator Framework; United Nations Division for Sustainable Development: New York City, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- UN (United Nations). The CSD Theme Indicator Framework, 2nd ed.; United Nations Division for Sustainable Development: New York City, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- UN (United Nations). Indicators of Sustainable Development: Guidelines and Methodologies, 3rd ed.; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York City, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). What Tourism Managers Need to Know: A Practical Guide to the Development and Use of Indicators of Sustainable Tourism; UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization): Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). Agenda 21 for the Travel and Tourism Industry; UNWTO, WTTC and Earth Council Publication: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations; A guidebook; UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization): Spain, Madrid, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nordic Council. Arctic Social Indicators ASI II Implementation. In TemaNord 2010:519; Larsen, J.N., Schweitzer, P., Fondahl, G., Eds.; Nordic Council: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nordic Council. Arctic Social Indicators. In TemaNord 2014:568; Larsen, J.N., Schweitzer, P., Fondahl, G., Eds.; Nordic Council: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nordic Council. Indicators for Sustainable Development. 2017. Available online: https://www.norden.org/en/nordic-council-of-ministers/ministers-for-co-operation-mr-sam/sustainable-development/indicators-for-sustainable-development-1 (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Tuulentie, S.; Hovgaard, G.; Zinglersen, K.B.; Svartá, M.; Poulsen, H.H.; Söndergaard, M. The contradictory role of tourism in the northern peripheries: Overcrowding, overtourism and the importance of tourism for rural development. In Sharing Knowledge for Land Use Management: Decision-Making and Expertise in Europe’s Northern Periphery; McDonagh, J., Tuulentie, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J.; Varnajot, A. The Arctic in tourism: Complementing and contesting perspectives on tourism in the Arctic. Polar Geogr. 2019, 42, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Selvaag, S.K.; Aas, O.; Gundersen, V. Linking visitors’ spatial preferences to sustainable visitor management in a Norwegian national park. Eco Mont. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Sæþórsdóttir, A.D.; Noordhuizen, J.; Nijkrake, W. Sustainable Leisure Landscapes in Icelandic Rural Communities: A Multidisciplinary Approach. J. Manag. Sustain. 2018, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Kristjánsdóttir, K.R.; Björnsson, G. Þróun Sjálfbærnivísa fyrir Ferðamennsku á Friðlýstum Svæðum [Development of Sustainability Indicators for Tourism in Protected Areas]; University of Iceland, The Icelandic Ministry of Industries and Innovation: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, J.; Tuulentie, S. (Eds.) Sharing Knowledge for Land Use Management: Decision-Making and Expertise in Europe’s Northern Periphery; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, P.A. Indicators of sustainable development: Some lessons from capital theory. Ecol. Econ. 1991, 4, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B. The unrecognized threat to tourism. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.; Hamilton, K.; Atkinson, G. Measuring sustainable development: Progress on indicators. Environ. Dev. Econ. 1996, 1, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, S.; Ateljevic, I. Tourism, economic development and the global-local nexus: Theory embracing complexity. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 3, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hák, T.; Janoušková, S.; Moldan, B. Sustainable Development Goals: A need for relevant indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, A.; Spangenberg, J.H. A guide to community sustainability indicators. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2000, 20, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, H. Sustainable tourism and the question of the commons. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 1065–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, B.; Twining-Ward, L. Seven Steps Towards Sustainability: Tourism in the Context of New Knowledge. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.C. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saarinen, J. Critical Sustainability: Setting the Limits to Growth and Responsibility in Tourism. Sustainability 2013, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristjánsdóttir, K.; Ólafsdóttir, R.; Ragnarsdóttir, K.V. Reviewing integrated sustainability indicators for tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaonson, J.; Tanguay, G.A. Strategy for selecting sustainable tourism indicators for the Gaspésie and Illes de la Madeleine regions. TÉOROS Spec. Issue 2012, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, H.C.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, J.; Kožić, I.; Krešić, D. Weighting indicators of tourism sustainability: A critical note. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 48, 312–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M.; Vinzón, L. Sustainability indicators of rural tourism from the perspective of the residents. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators; Methodology and User Guide; OECD and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, M. Guide to Sustainable Community Indicators, 2nd ed.; Hart Environmental Data: North Andover, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dymond, S.J. Indicators of Sustainable Tourism in New Zealand: A Local Government Perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 1997, 5, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council. The Global Sustainable Tourism Council Criteria version 1, 1st November 2013 and Suggested Performance Indicators version 1, 10 December 2013 for Destinations. 2013. Available online: https://www.gstcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Dest-_CRITERIA_and_INDICATORS_6-9-14.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- OECD. Green Growth Indicators. 2014. OECD Green Growth Studies: OECD Publishing. Available online: http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/environment/green-growth-indicators-2013_9789264202030-en#page141 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- ERDF (European Union Regional Development Fund). SUSTAIN. Measuring Costal Sustainability. A Guide for the Self-Assessment of Sustainability Using Indicators and a Means of Scoring Them; EU European Regional Development Fund, October 2012; Available online: https://www.sustain-eu.net/what_are_we_doing/measuring_coastal_sustainability.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Government of Iceland. Sustainable Development—A New Strategy for the Nordic Countries [Sjálfbær þróun-ný stefna fyrir Norðurlönd]. 2001. Available online: https://www.stjornarradid.is/media/umhverfisraduneyti-media/media/PDF_skrar/sjalfbaernordurlond.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Ozkan, U.R.; Schott, S. Sustainable Development and Capabilities for the Polar Region. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 1259–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NLSI (National Land Survey of Iceland). Topographical Map 1:500,000; NLSI: Akranes, Iceland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Björnsson, H. Jöklar á Íslandi [Glaciers in Iceland]; Forlagið: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- EAI (Environment Agency of Iceland). Þjóðgarðurinn Snæfellsjökull. Verndaráætlun 2010–2020 [Snæfellsjökull National Park. Protection plan 2010–2020]. 2010. Available online: Ust-2010_09-verndaraaetlun-snaefellsnes_www.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2019).

- Jóhannesson, H. Snæfellsnes. In Náttúruvá á Íslandi. Eldgos og Jarðskjálftar [Natural Disaster in Iceland. Volcanic Eruptions and Earthquakes] 2013; Sólnes, J., Sigmundsson, F., Bessason, B., Eds.; University Publication Press: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2010; pp. 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- CORINE. Corine Land Cover 2012 Raster Data. 2012. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/clc-2012-raster (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Runnström, M.C. Assessing the conditions of hiking trails in two popular tourists’ destinations in the Icelandic highlands. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2013, 3–4, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Iceland. Population by Municipalities. 2020. Available online: https://www.statice.is/statistics/population/inhabitants/municipalities-and-urban-nuclei/ (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Manning, T. Indicators of tourism sustainability. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.; Tribe, J. Sustainability Indicators for Small Tourism Enterprises—An Exploratory Perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, J.-H. Evaluating ecotourism sustainability from the integrated perspective of resource, community and tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.I.; Chia, K.W.; Ho, J.A.; Ramachandran, S. Seeking tourism sustainability—A case study of Tioman Island, Malaysia. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schmalensee, M.; Matthíasdóttir, T.; Stefánsson, R. Skref í rétta átt. Hverju hefur vinna að umhverfisvottun sveitarfélaga á Snæfellsnesi skilað? [Towards a Brighter Future. The Outcome of a Decade of Environmental Certification of the Municipalities on the Snæfellsnes Peninsula (Iceland)]. 2015. Available online: http://nesvottun.is/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Skref_i_retta_att.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- McCool, S.F.; Butler, R.W.; Buckley, R.; Weaver, D.; Wheeller, B. Is Concept of Sustainability Utopian: Ideally Perfect but Impracticable? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2013, 38, 213–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackstock, K.L.; White, V.; McCrum, G.; Scott, A.; Hunter, C. Measuring responsibility: An appraisal of a Scottish National Park’s sustainable tourism indicators. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P. Projects with People: The Practice of Participation in Rural Development; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Icelandic Act no. 106/2000 on environmental impact assessment [Lög um mat á umhverfisáhrifum]. Available online: www.althingi.is (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Icelandic Act no. 105/2006 on strategic environmental assessment [Lög um umhverfismat áætlana]. Available online: www.althingi.is (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Esterberg, K.G. Qualitative Methods in Social Research; McGraw Hill: New York City, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mathevet, R.; Antona, M.; Barnaud, C.; Fourage, C.; Trébuil, G.; Aubert, S. Contexts and Dependencies in the ComMod Processes; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Therivel, R. Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment in Action; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Moore, S.; Dowling, R. Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts and Management, 2nd ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Environmental Indicators: OECD Core Set; Organization for Economic co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

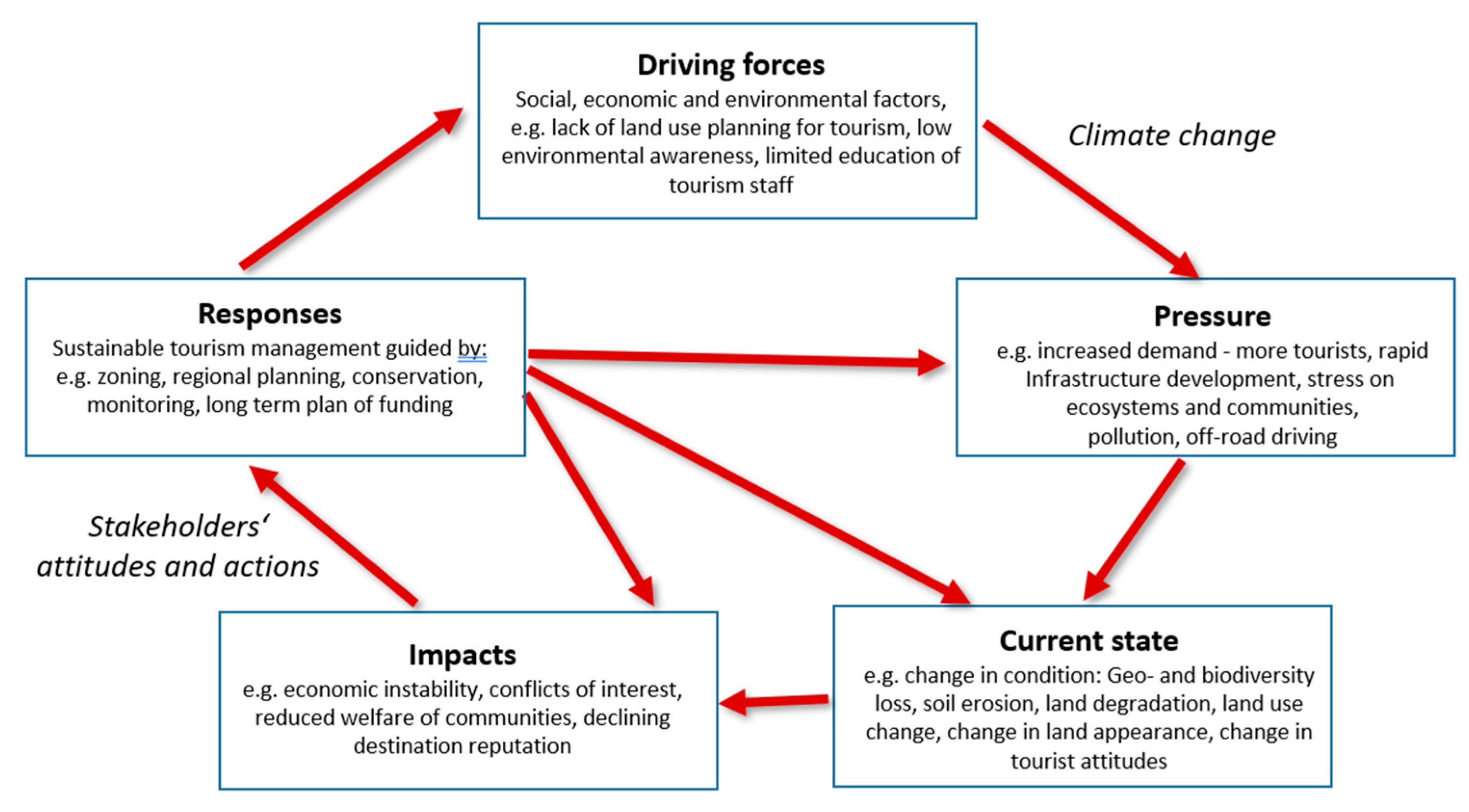

- Carr, E.R.; Wingard, P.M.; Yorty, S.C.; Thompson, M.C.; Jensen, N.K.; Roberson, J. Applying DPSIR to sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2007, 14, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1932–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.J.; Diduck, A.P.; Vespa, M. Public participation in sustainability assessment: Essential elements, practical challenges and emerging directions. In Handbook of Sustainability Assessment; Morrison-Saunders, A., Pope, J., Bond, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 349–374. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, M.C. An integrated approach to assess the impacts of tourism on community development and sustainable livelihoods. Community Dev. J. 2007, 44, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanguay, G.A.; Rajaonson, J.; Therrien, M.-C. Sustainable tourism indicators: Selection criteria for policy implementation and scientific recognition. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 862–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.D. Tourism Struggling as the Icelandic Wilderness is Developed. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 10, 334–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Sæþórsdóttir, A.D. Public Perception of Wilderness in Iceland. Land 2020, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Runnström, M.C. How Wild is Iceland? Assessing Wilderness Quality with Respect to Nature Based Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2011, 13, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Haraldsson, H. Tourism spatial dynamics and causal relations: A need for holistic understanding. In A Research Agenda for Tourism Geographies; Müller, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; Chapter 15; pp. 128–137. [Google Scholar]

- Tverijonaite, E.; Ólafsdóttir, R.; Thorsteinsson, T. Accessibility of protected areas and visitor behaviour: A case study from Iceland. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2018, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsson, H.V.; Ólafsdóttir, R. Evolution of Tourism in Natural Destinations and Dynamic Sustainable Thresholds over Time. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandström, S.; Sandström, P.; Nikula, A. Who is the public and where is participation in participatory GIS and public participation GIS. In Sharing Knowledge for Land Use Management: Decision-Making and Expertise in Europe’s Northern Periphery; McDonagh, J., Tuulentie, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). Tourism and the SDGs; UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization): Madrid, Spain, 2017; Available online: http://www2.unwto.org/content/tourism-and-sdgs (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Júlíusson, Á.D. Farmers’ perception on land cover changes in NE Iceland. Land Degrad. Dev. 2000, 11, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, J.; Árnason, Þ.; Ólafsdóttir, R. Implications of Climate Change on Nature-Based Tourism Demand: A Segmentation Analysis of Glacier Site Visitors in Southeast Iceland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, J.; Johansson, E.L.; Olsson, L. Harnessing local knowledge for scientific knowledge production: Challenges and pitfalls within evidence-based sustainability studies. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Conventional Indicators (Simple) | Sustainability Indicators (Complex) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics |

|

|

| Purpose |

|

|

| Benefits |

|

|

| Flaws |

|

|

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Research and Organization | Indicators’ Development | Implementation |

|

|

|

| Economy | Society and Wellbeing | Environment | Governance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected key indicator | Local stakeholders suggested change | Selected key indicator | Local stakeholders suggested change | Selected key indicator | Local stakeholders suggested change | Selected key indicator | Local stakeholders suggested change | |

| 1 | Job opportunities and the labor market around the national park | Job opportunities and the labor market | Population growth around the national park | Population growth | Environmental certifications and opportunities for environmentally friendly operations | Environmentally friendly management | Sustainable development policymaking | |

| 2 | Opportunities for innovation | Opportunities for local innovation | Quality of service | Biodiversity | Land use strategy tourism development | Zoning and regional planning of tourism | ||

| 3 | Economic standard of living and pricing | Travel behavior and tourists needs | Travel behavior and length of stay | Geodiversity | Sustainability monitoring | |||

| 4 | Seasonal and all year residence | Locals’ experience of tourism | Residents’ experience of tourism | Coastal erosion | National park’s human resources and knowledge of sustainable development | |||

| 5 | Seasonal work | National park employees’ view of tourists | Off-road driving | Public participation in policymaking | ||||

| 6 | Income from tourism | Direct income from tourism | Contentment and living standards of tourism employees | Waste management | Long term appropriation of funding for the national park | |||

| 7 | Modes of transport and traffic | Transportation and traffic | Tourists’ satisfaction | Tourists’ experience and satisfaction | Air pollution and climate change | Air pollution | Locals’ experience of the national park | Residents’ experience of the national park |

| 8 | Condition of roads and parking areas | Status of equality in society | Local equality | Energy utilization | Energy use | |||

| 9 | Sanitary facilities for tourists | Lavatories and other sanitary facilities for tourists | Education and training | Residents’ education and training | Nature conservation | |||

| 10 | Import of labor | Leave out | Local image and culture according to residents | Tourists’ impact on soil and vegetation | Carrying capacity of vegetation and soil | |||

| 11 | Import of goods | Leave out | Locals sustainability and environmental awareness | Sustainability and environmental awareness of residents | Seasonal vegetation and soil carrying capacity | Leave out | ||

| 12 | Local production of goods and services | Local production and utilization of goods and services | Sustainability and environmental awareness of tourists | Management of freshwater resources | Freshwater resources | |||

| 13 | Residents‘ public health and safety | Residents’ public health | ||||||

| New | Indirect income from tourism | Climate change Cultural heritage and history | Safety issues and information flow to tourists | |||||

| Monitoring Practical | Monitoring Partially Practical | Monitoring Impractical | ||

| Monitoring of an indicator is practical given the current circumstances. The foundational data and measurements exist, at least at a national level, and the monitoring can be based on those. | Only a part of the data and measurements are available; the measurements are not compatible and cannot give an overall picture of the area’s sustainability. | Monitoring is impractical because of a lack of data and measurements related to this indicator. | ||

| Economy | 3 | 6 | 2 | 11 |

| Society and wellbeing | 3 | 6 | 4 | 13 |

| Environment | 8 | 2 | 3 | 13 |

| Governance | 0 | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| TOTAL | 14 (31%) | 20 (44%) | 11 (25%) | 45/100 |

| DPSIR | Sustainability Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy | Society and Wellbeing | Environment | Governance | |

| Driving forces | Population growth Local image and culture according to residents Sustainability and environmental awareness of tourists | |||

| Pressure | Transportation and traffic Direct income from tourism | Travel behavior and length of stay | Environmentally friendly management Waste management Energy use Off-road driving | |

| Current state | Job opportunities and the labor market Economic standard of living and pricing Seasonal and all year residence Condition of roads and parking areas Indirect income from tourism Seasonal work | Sustainability and environmental awareness of residents Residents’ public health Quality of service Contentment and living standards of tourism employees National park employees’ views of tourists | Carrying capacity of vegetation and soil Biodiversity Geodiversity Air pollution Coastal erosion Fresh water resources | Residents’ experience of the national park National park’s human resources and knowledge of sustainable development |

| Impacts | Residents’ experience of tourism Tourists’ experience and satisfaction Local equality | Climate change | ||

| Responses | Local production and utilization of goods and services Lavatories and other sanitary facilities for tourists Opportunities for local innovation | Residents’ education and training | Nature conservation Cultural heritage and history | Sustainable development policy making Long-term appropriation of funding for the national park Zoning and regional planning of tourism Sustainability monitoring Public participation in policymaking Safety issues and information flow to tourists |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ólafsdóttir, R. The Role of Public Participation for Determining Sustainability Indicators for Arctic Tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010295

Ólafsdóttir R. The Role of Public Participation for Determining Sustainability Indicators for Arctic Tourism. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010295

Chicago/Turabian StyleÓlafsdóttir, Rannveig. 2021. "The Role of Public Participation for Determining Sustainability Indicators for Arctic Tourism" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010295