Spatial Variation in Tourism and Investment Potential in the Context of Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Staszowski County

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Spatial Variation in Tourism

2.2. Investment Potential in Tourism

- market and financial conditions, which influence on the decision-making about investment in tourism,

- demographic and psychological conditions concerning the perception of the region by potential tourists and the tradition of recreation,

- technological and ecological conditions related to the possibility of better adaptation of tourist values or use by tourists and protection against degradation,

2.3. Tool Supporting Tourism Sustainable Development

3. Materials and Methods

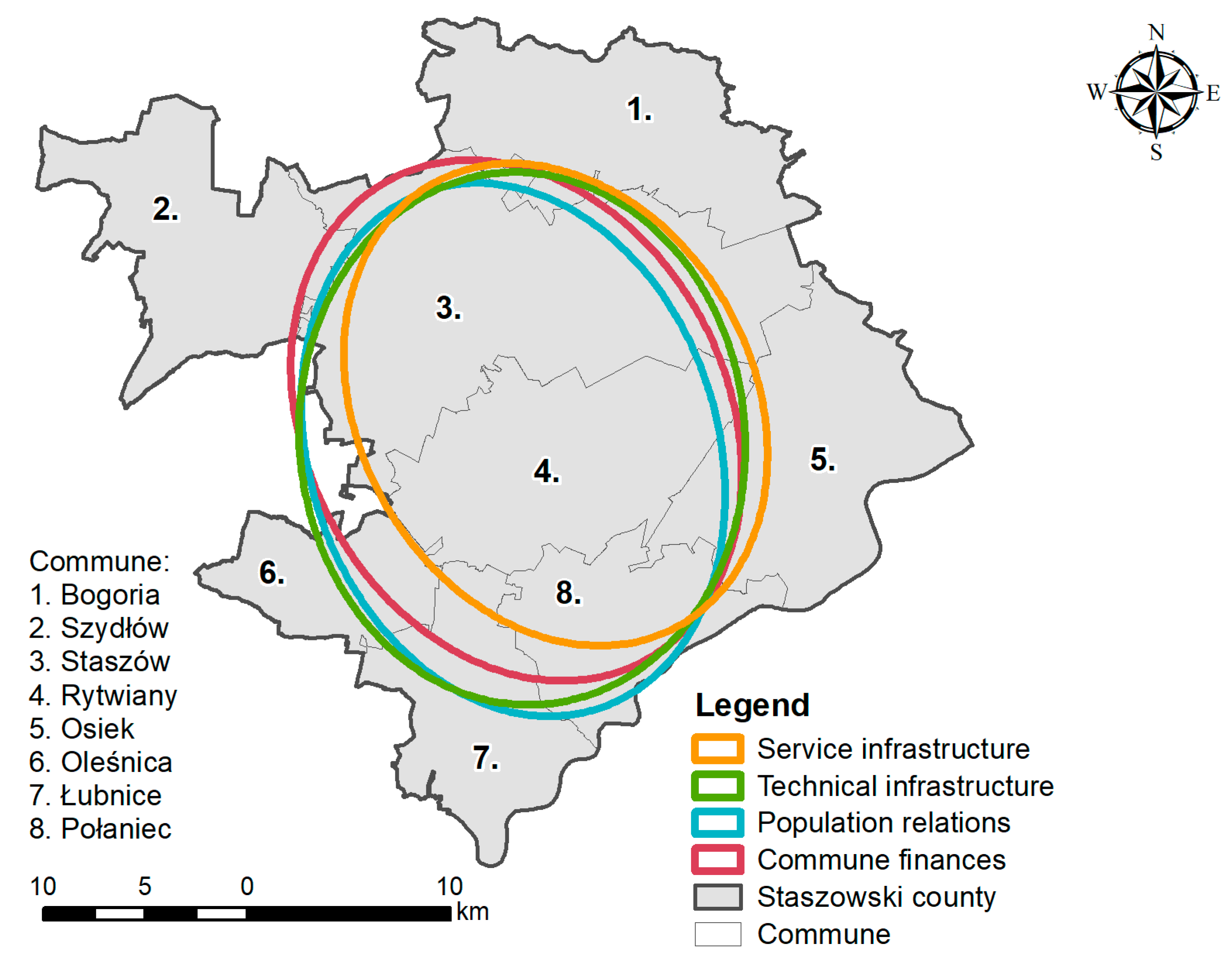

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methodology

- nij—normalized value of the j-th indicator in the i-th commune,

- yij—value of j-th indicator in the i-th commune,

- yj max—maximum value of the j-th indicator among analysis communes.

4. Results

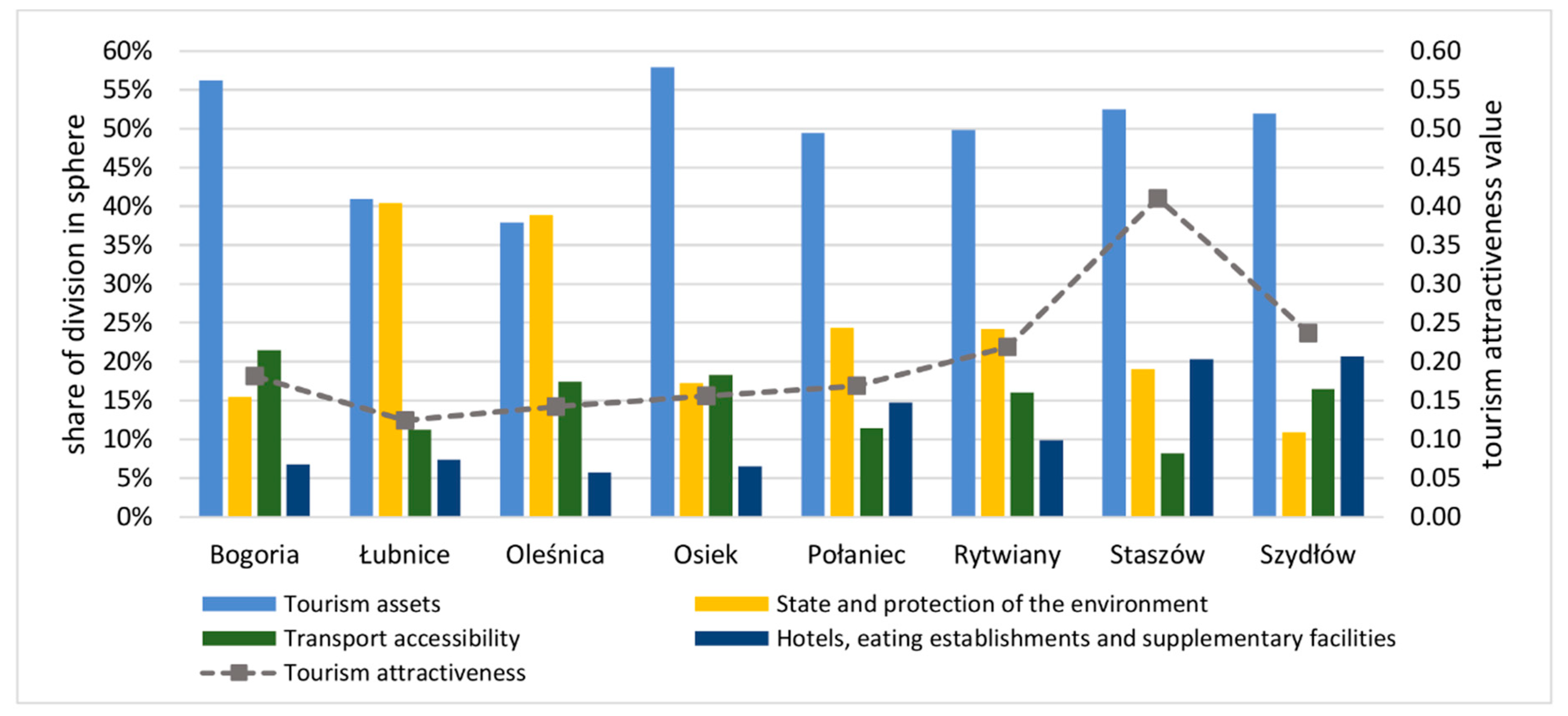

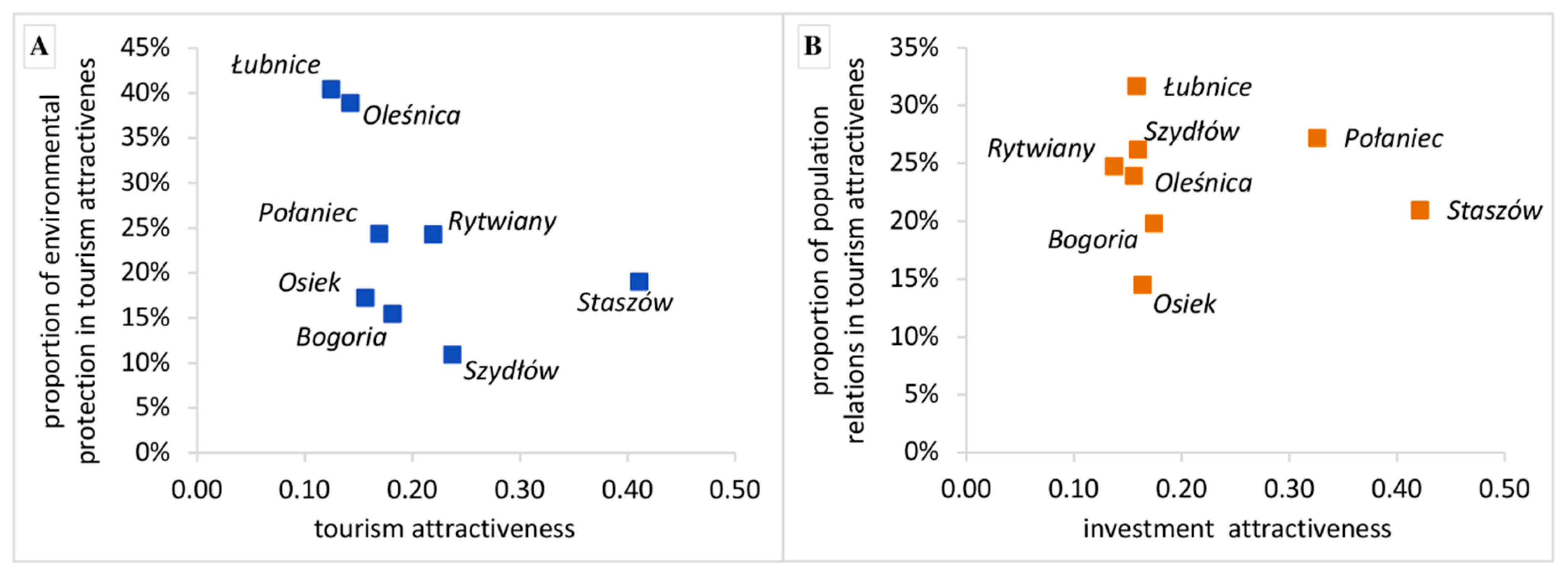

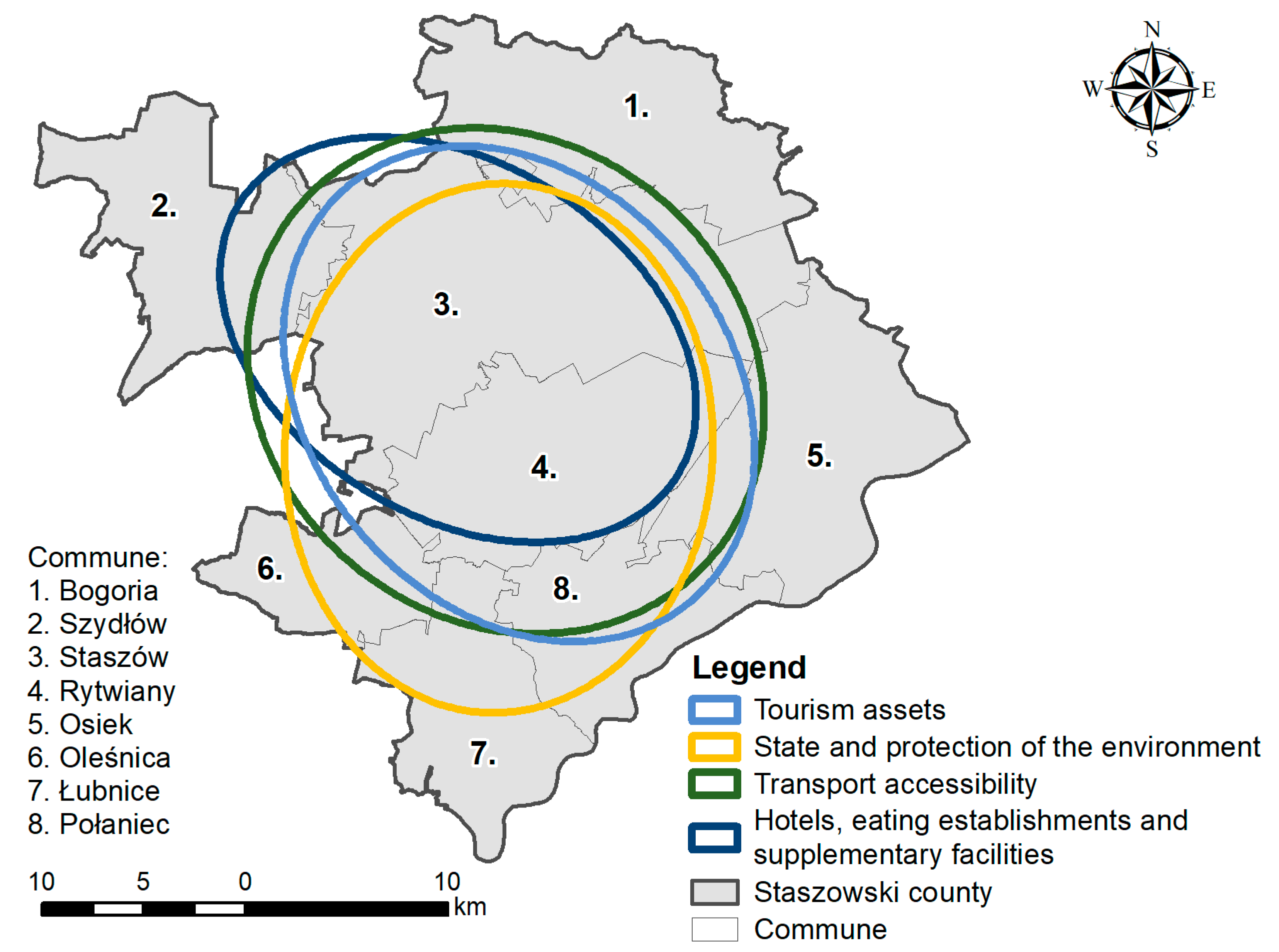

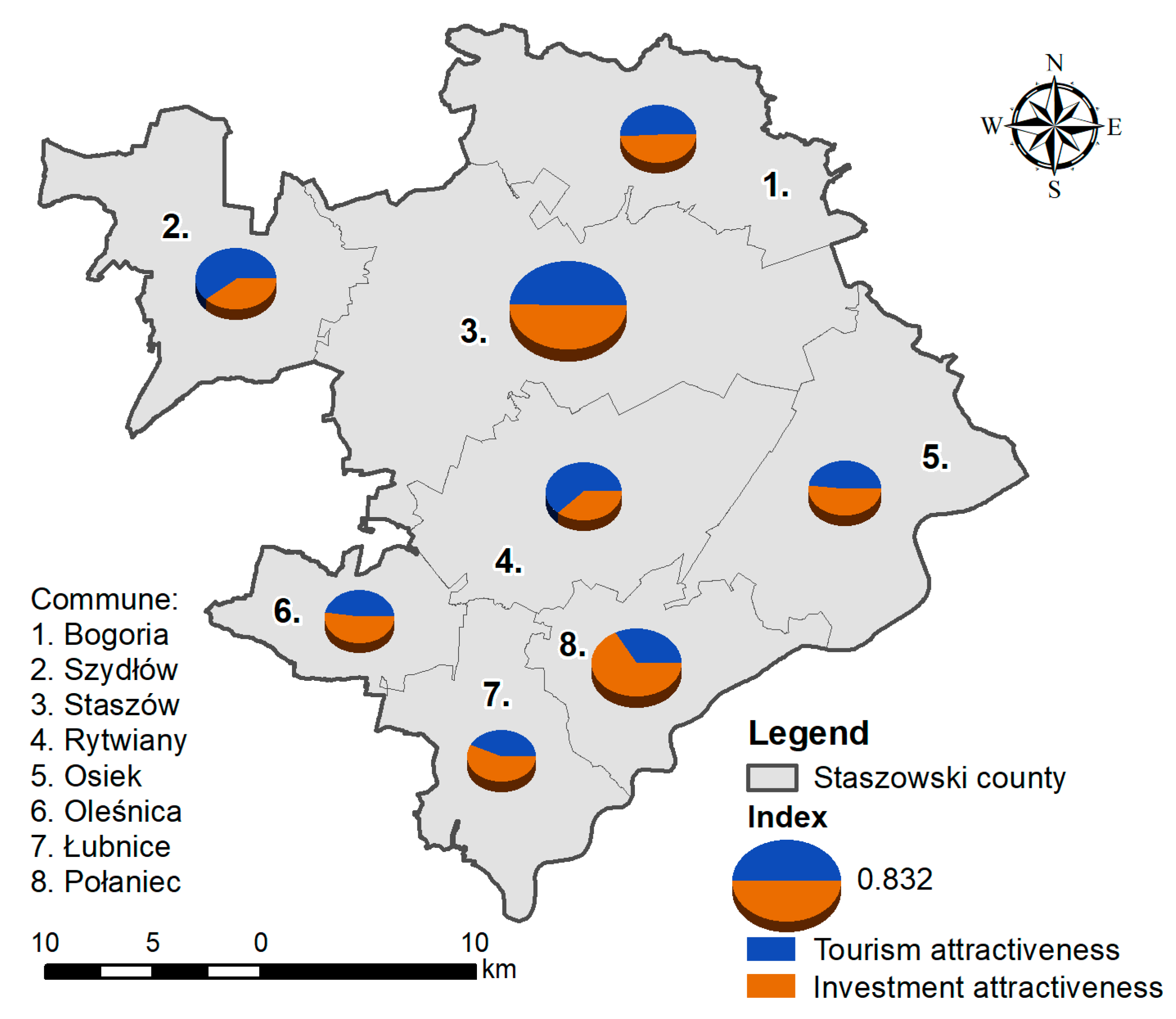

4.1. Assessment of Tourism Attractiveness

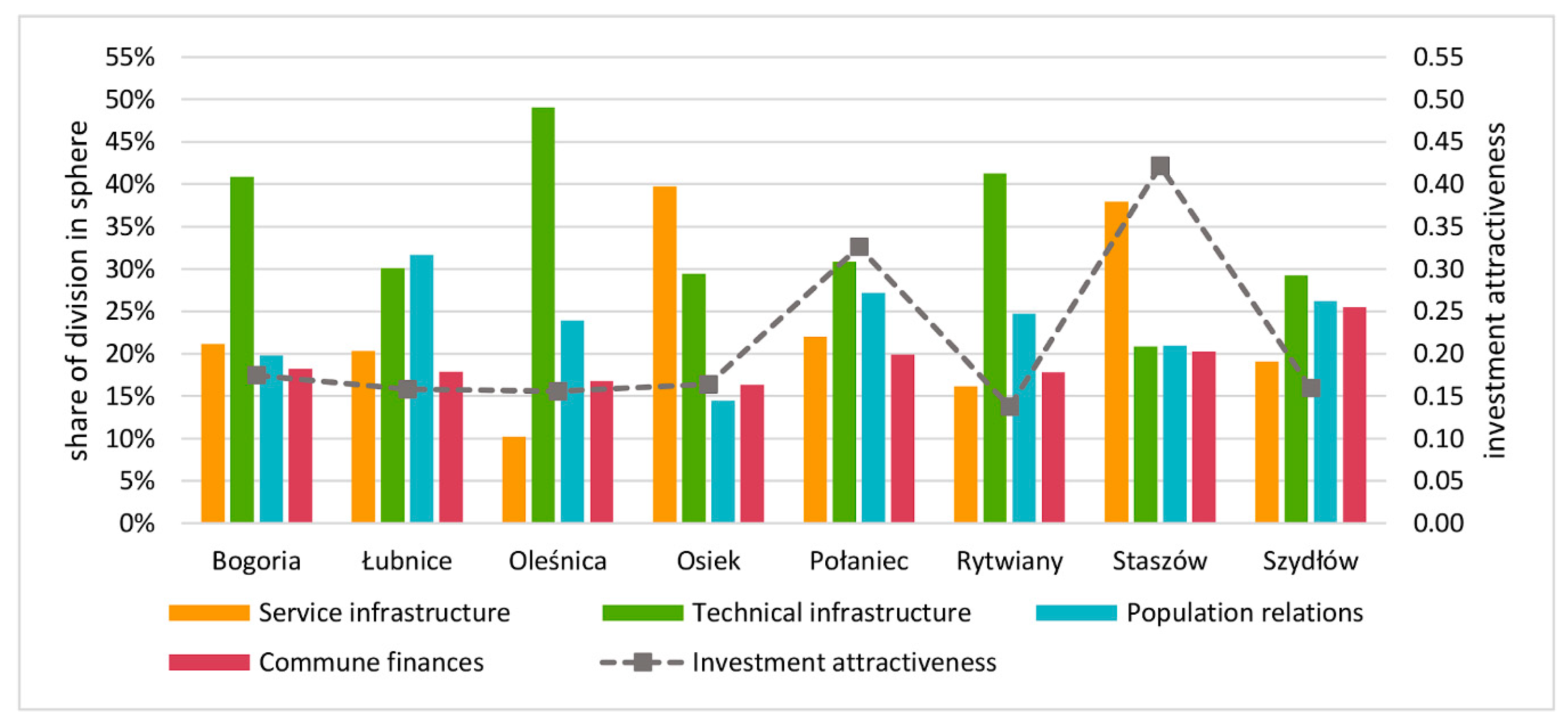

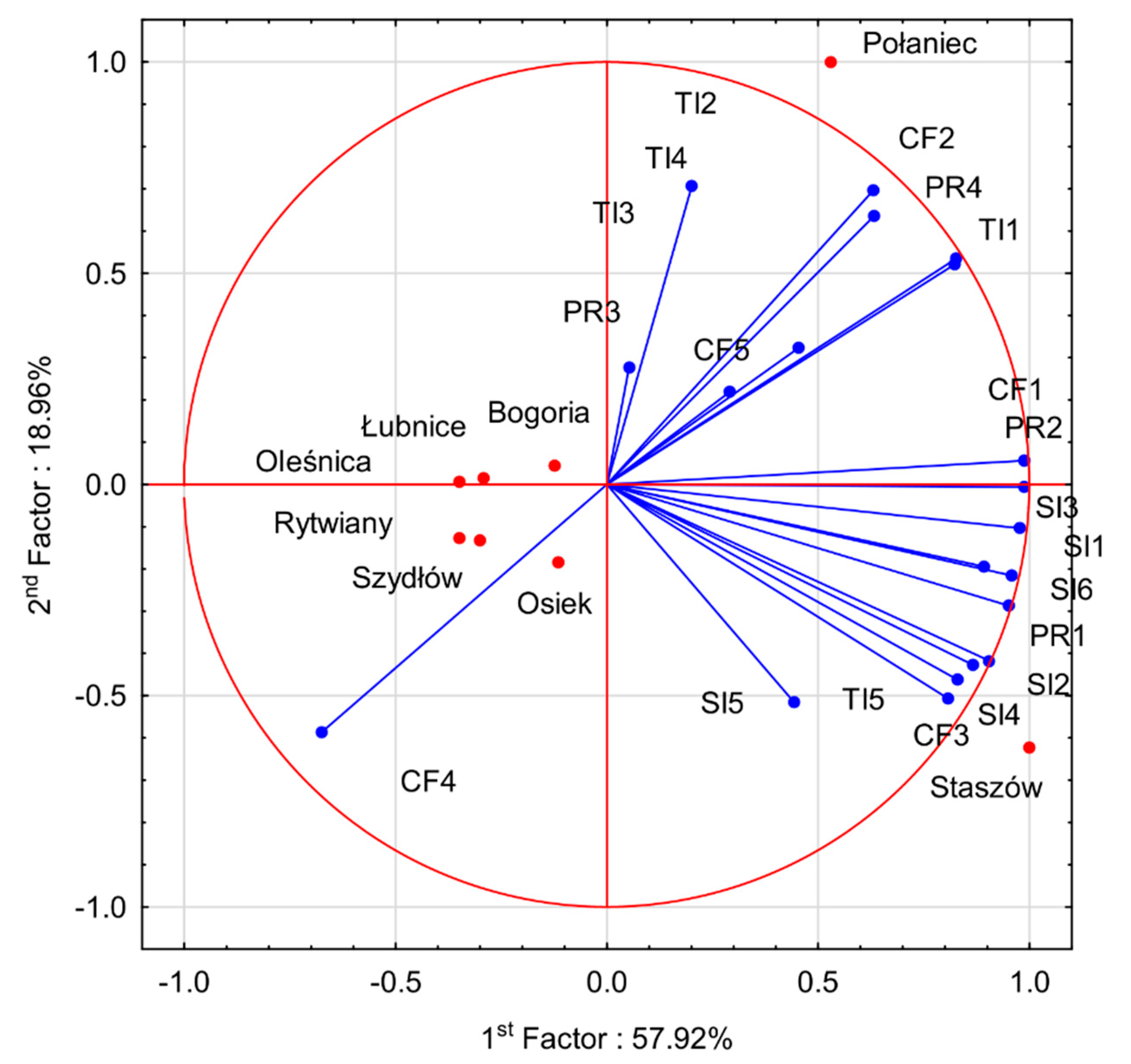

4.2. Assessment of Attractiveness for Investors

4.3. Synthetic Measure of Total Determinants of the Development of Tourism in the Communes

4.4. Suggestions for Development in Individual Communes

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The most attractive communes in terms of tourism, i.e., Staszów and Szydłów, and the most attractive communes for investors, i.e., Staszów and Połaniec, have lower indicators of sustainable development associated with environmental protection than the average for the county.

- Staszowski County has tourism and investment potential as well as the potential to be a significant centre of development of tourism, but it should strive for more sustainable development.

- Communes with greater tourism potential, such as Staszów and Szydłów, are situated in the centre of the county, and should be more focused on their nature and cultural assets, while at the same time taking care to ensure appropriate tourism assets and environmental protection.

- Communes such as Łubnica and Połaniec, situated in the south-eastern part of the county, are distinguished by their greater investment potential, and should be more focused on the development of suitable technical and transport infrastructure in order to increase the number of potential investors.

- The study confirms the useful contribution of GIS tools in the assessment of tourism and investment potential. They are especially useful to the identification of spatial patterns, which might be helpful in a more sustainable development of the region. The other contribution for the existing literature is identification of the lack of cluster structure for tourism in the region, which have some tourism and investment potential, but tourism has only an indirect impact on the economy. However, due to small sample size, the research should be carried out in other regions with similar tourism and investment potential.

- The study can be used as a basis for drawing up planning documents at the local level to support sustainable development in the area. They can also be used as a basis for future cooperation between communes, including cooperation aimed at supporting the competitiveness of the county. This will help to better exploit the common assets of the region and its sustainable development.

- The study should be repeated in subsequent years, particularly in 2021, in order to track the changes in the values of the parameters analysed and to evaluate progress in the sustainable development of tourism in the study area. This research can also be helpful in assessing the development of tourism after two phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 1–383. [Google Scholar]

- Kapera, I. Sustainable tourism development efforts by local governments in Poland. Sustain. Cities. Soc. 2018, 40, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme; United Nations World Tourism Organization. Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers; UNEP: Paris, France; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2005; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.S.; García-Moruno, L.; Hernández-Blanco, J.; Jaraíz-Cabanillas, F.J. An operational method to supporting siting decisions for sustainable rural second home planning in ecotourism sites. Land Use Policy 2014, 41, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva-Shapira, K.A. New paradigms in city tourism management: Redefining destination promotion. J. Travel. Res. 2007, 46, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timur, S.; Getz, D. Sustainable tourism development: How do destination stakeholders perceive sustainable urban tourism? Sustain. Dev. 2009, 17, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimoska, T.; Petrevska, B. Indicators for sustainable tourism development in Macedonia. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Business, Economics and Finance “From Liberalization to Globalization: Challenges in the Changing World”, Stip, North Macedonia, 13–15 September 2012; pp. 389–400. [Google Scholar]

- Vallone, C.; Orlandini, P.; Cecchetti, R. Sustainability and innovation in tourism services: The Albergo Diffuso case study. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf, J. Tourism in the system of industrial society. Ann. Tour. Res. 1986, 13, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A. Turystyka zrównoważona; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2001; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Sport and Tourism. Tourism Development Programme Until 2020; Ministry of Sport and Tourism: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pałka, E. The development of tourist sector in the Świętokrzyskie voivodship in background of Poland. Infrastruct. Ecol. Rural. Areas 2011, 2, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Revisiting several basic geographical concepts: A social sensing perspective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2016, 71, 564–575. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, W.; Mika, M. Turystyka jak przedmiot badań naukowych. In Turystyka; Kurek, W., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2007; pp. 9–49. [Google Scholar]

- Warszyńska, J.; Jackowski, A. Podstawy Geografii Turyzmu; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Liszewski, S. Przestrzeń turystyczna. Turyzm 1995, 5, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wong, K.K. Spatial distribution of tourist flows to China’s cities. Tour. Geogr. 2012, 15, 338–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Huang, G.Q. Tourism supply chain management: A new research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gillmor, D.A. Evolving air-charter tourism patterns: Change in outbound traffic from the Republic of Ireland. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hare, G.; Barrett, H. Regional inequalities in the Peruvian tourist industry. Geogr. J. 1999, 165, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.Y.; Lin, H.L.; Wang, C.L. Industry-region position and economic performance of travel and tourism service industry: An agglomeration perspective. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, E.J. Tourism micro-clusters. Tour. Econ. 2003, 9, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.A.; Hassan, S. Investment and Tourism: Insights from the literature. J. Econ. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 10, 581–590. [Google Scholar]

- Romão, J.; Guerreiro, J.; Rodrigues, P.M. Territory and sustainable tourism development: A space-time analysis on European regions. Region 2017, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romão, J.; Saito, H. A spatial analysis on the determinants of tourism performance in Japanese Prefectures. Asia Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 2017, 1, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jędruch, M.; Furmankiewicz, M.; Kaczmarek, I. Spatial Analysis of Asymmetry in the Development of Tourism Infrastructure in the Borderlands: The Case of the Bystrzyckie and Orlickie Mountains. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2020, 9, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, P. Barrier E_ects of Borders: Implications for Border Crossing Infrastructures. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2012, 12, 150–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Rangel, M.C.; Sanchez Rivero, M. Spatial Imbalance Between Tourist Supply and Demand: The Identification of Spatial Clusters in Extremadura, Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruda, A. Exploring tourism possibilities using GIS-based spatial association methods. Geogr. Tech. 2016, 11, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nalej, M. Rozmieszczenie obiektów noclegowych w Łodzi w 2013 roku w świetle miar centrograficznych. Acta Univ. Lodziensis. Folia Geogr. Socio Oeconomica 2014, 16, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Majewska, J. Inter-regional agglomeration effects in tourism in Poland. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 408–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, J.; Trusklolaski, S. Spatial concentration of economic activity and competitiveness of Central European regions. In Challenges for International Business in Central and Eastern Europe; Wach, K., Kneževi’c, B., Šimurina, N., Eds.; Cracow University of Economics: Kraków, Poland, 2017; pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zarębski, P.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Oklevik, O. Tourism investment gaps in Poland. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Mamun, A.; Mitra, S. A methodology for assessing tourism potential: Case study Murshidabad District, West Bengal, India. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2012, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, E. Regionalne zróżnicowanie atrakcyjności turystycznej na przykładzie województwa świętokrzyskiego. Studium Vilnense A. 2020, 17, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kornak, A.S.; Rapacz, A. Zarządzanie Turystyką i Jej Podmiotami w Miejscowości i Regionie; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2001; pp. 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- Gawroński, K.; Król, K.; Gawrońska, G.; Leśniara, N. Spatial diversity of tourism attractiveness of the Nowy Sącz district, using the Wrocław taxonomic method. Geomat. Landmanagement Landsc. 2019, 2, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołembski, G. (Ed.) Regionalne Aspekty Rozwoju Turystyki; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw-Poznań, Poland, 1999; pp. 1–206. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B. Aktywność samorządu lokalnego jako element potencjału turystycznego na przykładzie wybranych gmin województwa zachodniopomorskiego. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Szczecińskiego 2010, 590, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guillet, B.D.; Zhang, H.Q.; Gao, B.W. Interpreting the mind of multinational hotel investors: Future trends and implications in China. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, W.; Turnpenny, J.; Nilsson, M.; Von Raggamby, A. A framework for tool selection and use in integrated assessment for sustainable development. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2007, 9, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schianetz, K.; Kavanagh, L.; Lockington, D. Concepts and tools for comprehensive sustainability assessments for tourism destinations: A comparative review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Tourism Indicator System. ETIS Toolkit for Sustainable Destination Management; Publications Office for the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Gao, B.W.; Zhang, M. A mathematical model for tourism potential assessment. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, P.; Faryadi, S. Potential Assessment of Nature-Based Tourism Destinations Using MCA Techniques (Case Study: Lavasan-e Koochak). J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 36, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Kreiner, N.; Wall, G. Evaluating tourism potential: A SWOT analysis of the Western Negev, Israel. Tourism 2007, 55, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Iatu, C.; Bulai, M. New approach in evaluating tourism attractiveness in the region of Moldavia (Romania). Int. J. Energy Environ. 2011, 5, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G. The development of indicators for sustainable tourism: Results of a Delphi survey of tourism researchers. Tour. Manage. 2001, 22, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano-Oyola, M.; Blancas, F.J.; González, M.; Caballero, R. Sustainable tourism tags to reward destination management. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 250, 109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour. Manage. 2019, 71, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzo-Navarro, M.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M.; Vinzón, L. Sustainability indicators of rural tourism from the perspective of the residents. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.; Shaw, J. The ecological footprint as a key indicator of sustainable tourism. Tourism Manage. 2007, 28, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Lindo, P.; Vanderschaeghe, M. Can community-based tourism contribute to development and poverty alleviation? Lessons from Nicaragua. Curr. Issues. Tour. 2011, 14, 725–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; González, M.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; Perez, F. The assessment of sustainable tourism: Application to Spanish coastal destinations. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Kanie, N.; Kim, R.E. Global governance by goal-setting: The novel approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Curr. Opin. Env. Sust. 2017, 26–27, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondracki, J. Geografia regionalna Polski; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2009; pp. 1–441. [Google Scholar]

- Starostwo Powiatowe w Staszowie. Strategia Rozwoju Powiatu Staszowskiego na lata 2016–2025; Starostwo Powiatowe w Staszowie: Staszów, Poland, 2016; pp. 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Durydiwka, M. Tourist function in rural areas of Poland. Spacial diversity and changing trends. Misc. Geogr. 2013, 17, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witkowska-Dąbrowska, M. Ocena potencjału turystycznego powiatu o wysokich walorach środowiskowych. In Tourism in the Development of Rural Areas; Sikorska-Wolak, A., Ed.; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2007; pp. 463–477. [Google Scholar]

- Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A.; Zawora, T. Wybrane metody oceny atrakcyjności agroturystycznej terenów wiejskich. Infrastruct. Ecol. Rural. Areas 2011, 2, 235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Pukowiec, K.; Kurda, W. Ocena atrakcyjności turystyczno-rekreacyjnej gmin powiatu Lublinieckiego. Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Przymierza Rodzin w Warszawie 2013, 11, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lisiak, M.; Opala, A.; Borowiak, K. The concept of tourism development as a factor increasing the tourism potential of rural communes—A case study. Studia Obszarów Wiejskich 2016, 44, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robaszkiewicz, K.; Lisiak, M.; Borowiak, K.; Kanclerz, J. The concept of tourism enrichment potential of Witkowo commune concerning Gniezno county area. Infrastruct. Ecol. Rural. Areas 2016, IV/2, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Król, K.; Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A.; Zdonek, D. Assessment of the attractiveness of the tourist and recreation area of Bielsko County. Zesz. Nauk. Organ. i Zarządzanie Politech. Śląska 2020, 144, 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A.; Lisiak, M. Evaluation of the tourism and recreational space of Lubaczowski County, Poland. J. Water Land Dev. 2020, 44, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Świstak, E.; Świątkowska, M. Zróżnicowanie przestrzenne bazy noclegowej jako determinanta ruchu turystycznego w Polsce. Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2016, 34, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polska Agencja Rozwoju Turystyki SA. In Strategia Rozwoju Turystyki w Województwie Świętokrzyskim na Lata 2006–2014; Ministerstwo Sportu i Turystyki: Warsaw, Poland, 2005.

- Derek, M.; Woźniak, E.; Kulczyk, S. Clustering nature-based tourists by activity. Social, economic and spatial dimensions. Tour. Manage. 2019, 75, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jażdżewska, I. The use of centrographic measures in analysing the dispersion of historic factories, villas and palaces in Łódź (Poland). Folia Geogr. 2018, 60, 50. [Google Scholar]

| Division | Feature | Symbol | Unit of Measurement | Weight | Character |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tourism assets | forest area | TA1 | ha | 0.15 | + |

| meadow and pasture area | TA2 | ha | 0.04 | + | |

| other land and wasteland | TA3 | ha | 0.08 | + | |

| protected areas | TA4 | ha | 0.12 | + | |

| river | TA5 | number | 0.08 | + | |

| lake | TA6 | number | 0.08 | + | |

| fairs, exhibitions and events | TA7 | number | 0.08 | + | |

| museums | TA8 | number | 0.05 | + | |

| churches | TA9 | number | 0.06 | + | |

| palace and castles | TA10 | number | 0.09 | + | |

| historic monuments | TA11 | number | 0.09 | + | |

| tourist trail length | TA12 | km | 0.08 | + | |

| state and protection of the environment | wastewater treatment plant capacity relative to volume of wastewater to be treated | EP1 | % | 0.25 | + |

| amount of waste generated during the year | EP2 | t | 0.25 | - | |

| water consumption for the needs of the national economy and population during the year | EP3 | hm3 | 0.25 | - | |

| number of home sewage treatment plants | EP4 | number | 0.25 | + | |

| transport accessibility | length of regional roads | TRA1 | km | 0.50 | + |

| length of county roads | TRA2 | km | 0.50 | + | |

| hotels, eating establishments and supplementary facilities | hotels | HC1 | number of facilities | 0.30 | + |

| boarding houses | HC2 | number of facilities | 0.25 | + | |

| restaurants and cafés | HC3 | number of facilities | 0.25 | + | |

| swimming pools | HC4 | number of facilities | 0.04 | + | |

| swimming areas | HC5 | number of facilities | 0.05 | + | |

| sports fields | HC6 | number of facilities | 0.06 | + | |

| horse riding centres, studs | HC7 | number of facilities | 0.05 | + | |

| service infrastructure | petrol stations | SI1 | number of facilities | 0.30 | + |

| pharmacies | SI2 | number of facilities | 0.08 | + | |

| banks and money exchange offices | SI3 | number of facilities | 0.20 | + | |

| post and telecommunication centres | SI4 | number of facilities | 0.30 | + | |

| outpatient clinics and health centres | SI5 | number of facilities | 0.06 | + | |

| dental surgeons | SI6 | number of facilities | 0.06 | + | |

| technical infrastructure | proportion of residential buildings connected to the water network in total residential buildings | TI1 | % | 0.20 | + |

| water distribution network length | TI2 | km per 100 km2 | 0.20 | + | |

| proportion of residential buildings connected to the sanitary drainage network in total residential buildings | TI3 | % | 0.20 | + | |

| sanitary drainage network length | TI4 | km per 100 km2 | 0.20 | + | |

| population using gas supply network | TI5 | % | 0.20 | + | |

| population relations | total number of inhabitants | PR1 | number of people | 0.15 | + |

| total number of employed people | PR2 | number of people | 0.20 | + | |

| unemployment rate | PR3 | % | 0.30 | + | |

| population density | PR4 | number of people per km2 | 0.35 | + | |

| commune finances | commune incomes | CF1 | PLN | 0.40 | + |

| total value of signed grant agreements | CF2 | PLN | 0.10 | ||

| the proportion of commune’s investments in total expenditure from the communal budget | CF3 | % | 0.20 | + | |

| proportion of grants and subsidies in total income of the commune | CF4 | % | 0.10 | + | |

| expenditure on public roads | CF5 | PLN | 0.20 | + |

| Sphere | Weight of Sphere | Division | Weight of Division |

|---|---|---|---|

| tourism attractiveness | 0.50 | tourism assets | 0.60 |

| state and protection of the environment | 0.10 | ||

| transport accessibility | 0.10 | ||

| hotels, eating establishments and supplementary facilities | 0.20 | ||

| investment attractiveness | 0.50 | service infrastructure | 0.32 |

| technical infrastructure | 0.25 | ||

| population relations | 0.23 | ||

| commune finances | 0.20 |

| Analysis Division | Moran’s I index | z-Score | p-Value | Spatial Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tourism assets | 0.031 | 0.780 | 0.435 | random |

| state and protection of the environment | −0.734 | −2.518 | 0.012 | dispersed |

| transport accessibility | 0.302 | 1.737 | 0.082 | clustered |

| hotels, eating establishments and supplementary facilities | 0.183 | 1.531 | 0.126 | random |

| service infrastructure | −0.323 | −0.974 | 0.330 | random |

| technical infrastructure | −0.612 | −1.817 | 0.069 | dispersed |

| population relations | −0.597 | −1.816 | 0.069 | dispersed |

| commune finances | −0.374 | −1.007 | 0.314 | random |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lisiak-Zielińska, M.; Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A. Spatial Variation in Tourism and Investment Potential in the Context of Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Staszowski County. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010003

Lisiak-Zielińska M, Ziernicka-Wojtaszek A. Spatial Variation in Tourism and Investment Potential in the Context of Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Staszowski County. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleLisiak-Zielińska, Marta, and Agnieszka Ziernicka-Wojtaszek. 2021. "Spatial Variation in Tourism and Investment Potential in the Context of Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Staszowski County" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010003