An Empirical Investigation and Conceptual Model of Perceptions, Support, and Barriers to Marketing in Social Enterprises in Bangladesh

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Underpinnings

Technology–Organisation–Environment (TOE) Framework

3. Methodology and Methods

3.1. Data Collection Methods

3.2. Sampling Technique

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

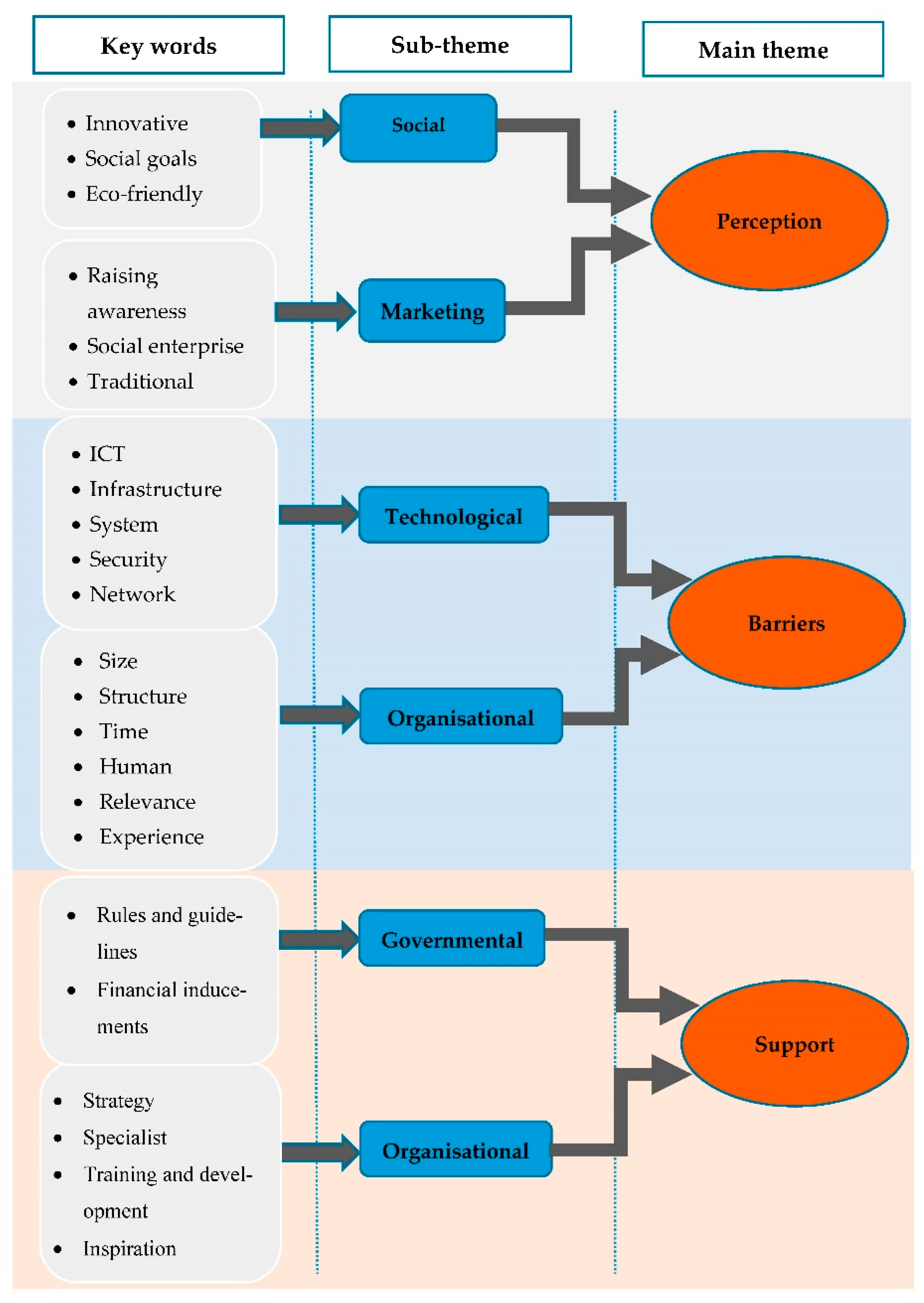

4.1. Main Theme 1: Perception

4.1.1. Sub-Theme 1: SE

4.1.2. Sub-Theme 2: Marketing

4.2. Main Theme 2: Barriers

4.2.1. Sub-Theme 1: Technological Barriers

4.2.2. Sub-Theme 2: Organisational Barriers

4.3. Main Theme 3: Support

4.3.1. Sub-Theme 1: Governmental Support

4.3.2. Sub-Theme 2: Organisational Support

5. Discussion

6. Conceptual Framework

7. Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haller, S.; Siedschlag, I. Determinants of ICT adoption: Evidence from firm-level data. Appl. Econ. 2011, 43, 3775–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivetbodee, S.; Igel, B.; Kraisornsuthasinee, S. Creating Social Value Through Social Enterprise Marketing: Case Studies from Thailand’s Food-Focused Social Entrepreneurs. J. Soc. Entrep. 2017, 8, 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, M.; Vermeulen, E.P.M. Alternatives to Silicon Valley: Building Your Global Business Anywhere. In Lex Research Topics in Corporate Law & Economics Working Paper No. 2015-2; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Wittmann, X.; Peng, M.W. Institution-based barriers to innovation in SMEs in China. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2011, 29, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei-Skillern, J. Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebold, N.; Günzel-Jensen, F.; Müller, S. Balancing dual missions for social venture growth: A comparative case study. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 31, 710–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, C.; Ray, S. Social enterprise marketing: Review of literature and future research agenda. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 38, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykkyläinen, S.; Ritala, P. Business model innovation in social enterprises: An activity system perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G. Enterprising Nonprofits. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Iankova, S.; Davies, I.; Archer-Brown, C.; Marder, B.; Yau, A. A comparison of social media marketing between B2B, B2C and mixed business models. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 81, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Sinha, J. E-Commerce: Adoption Barriers in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) in India. SMS J. Entrep. Innov. 2016, 2, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamat, A.; Shahkat Ali, M.; Hamid, N. Factors influencing the adoption of social media in small and medium enterprises (SMEs). In Proceedings of the SOCIOINT 2017—4th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities, Dubai, UAE, 10–12 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.E.; Lancaster, G. Understanding technologically induced customer services in the Nigerian banking sector: The internet as a post-modern phenomenon. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2016, 15, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; Khan, M.; Athoi, A.; Islam, F.; Lynch, A. The State of Social Enterprise in Bangladesh. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/bc-report-ch2-bangladesh-digital_0.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Weerakoon, C.; McMurray, A.J.; Rametse, N.; Arenius, P. Knowledge creation theory of entrepreneurial orientation in social enterprises. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 834–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lim, U. Social Enterprise as a Catalyst for Sustainable Local and Regional Development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, K.K.Y.; Chau, P.Y.K. A Perception-Based Model for EDI Adoption in Small Businesses Using a Technology Organisation-Environment Framework. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S. Energy Cooperation between India and Bangladesh: Economics and Geopolitics. In The Geopolitics of Energy in South Asia; Lall, M., Ed.; ISEAS Publications: Singapore, 2009; pp. 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.H.; Lee, J.-H. A Study on the Effects of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Learning Orientation on Financial Performance: Focusing on Mediating Effects of Market Orientation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjojo, H.; Gunawan, S. Indigenous Tradition: An Overlooked Encompassing-Factor in Social Entrepreneurship. J. Soc. Entrep. 2019, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Garg, I.; Sharma, G. Social Entrepreneurship as a Path for Social Change and Driver of Sustainable Development: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wry, T.; York, J. An Identity-Based Approach to Social Enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Foss, N.; Linder, S. Social Entrepreneurship Research: Past Achievements and Future Promises. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S.; Warnick, B.J. The Downside of Blended Value and Hybrid Organizing. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 2015, p. 10130. [Google Scholar]

- Bacq, S.; Hartog, C.; Hoogendoorn, B. A Quantitative Comparison of Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Toward a More Nuanced Understanding of Social Entrepreneurship Organizations in Context. J. Soc. Entrep. 2013, 4, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.; Santos, F. Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 972–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, P. Social enterprise sustainability revisited: An international perspective. Soc. Enterp. J. 2016, 12, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinch, S.; Sunley, P. Social enterprise and neoinstitutional theory. Soc. Enterp. J. 2015, 11, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.; Crompton, H. Business practices in social enterprises. Soc. Enterp. J. 2006, 2, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Jonaed Kabir, M.; Solaiman, D. Social Entrepreneurship (SE) Development in Bangladesh. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. E Mark. 2015, 15. Available online: https://journalofbusiness.org/index.php/GJMBR/article/view/1685 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Brink, T. B2B SME management of antecedents to the application of social media. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 64, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Lancaster, G. Consumption and communication perspectives of IT in a developing economy. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, R. Strategic Marketing and Marketing Strategy: Domain, Definition, Fundamental Issues and Foundational Premises. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Aggrawal, A. Revolutionising Marketing Through Social Networking Case Study of Indian SME. [Online]. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3094002 (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Atwong, C. A Social Media Practicum: An Action-Learning Approach to Social Media Marketing and Analytics. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2016, 25, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaga, W.; Chacour, S. Measuring Customer-Perceived Value in Business Markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2001, 30, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiweshe, N.; Ellis, D. Strategic Marketing for Social Enterprises in Developing Nations; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Fundamentals for an International Typology of Social Enterprise Models. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2017, 28, 2469–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, K. An exploratory study of social purpose business models in the United States. Non-Profit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 40, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuem, W.; Patel, A.; Howell, K.E.; Lancaster, G. An exploration of customers’ response to online service recovery initiatives. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 59, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe, L.M. Marketing Defined. Mark. News 2008, 42, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, C.R.; Kwong, C.C.Y.; Tasavori, M. Market orientation, market disruptiveness capability and social enterprise performance: An empirical study from the United Kingdom. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terziev, V.; Georgiev, M. Social Entrepreneurship: Support for Social Enterprises in Bulgaria. IJASOS Int. E-J. Adv. Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 744–749. [Google Scholar]

- Modi, P.; Mishra, D. Conceptualising market orientation in non-profit organisations: Definition, performance, and preliminary construction of a scale. J. Mark. Manag. 2010, 26, 548–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chao, P.; Huang, G. Modeling market orientation and organizational antecedents in a social marketing context: Evidence from China. Int. Mark. Rev. 2009, 26, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, T. Market Orientation Impact on Organisational Performance of Non-Profit Organisation (NPOs) Among Developing Countries. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2018, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Levy, S. Broadening the Concept of Marketing. J. Mark. 1969, 33, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulai Mahmoud, M.; Yusif, B. Market orientation, learning orientation, and the performance of nonprofit organisations (NPOs). Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2012, 61, 624–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linna, P. Bricolage as a means of innovating in a resource-scarce environment: A study of innovator-entrepreneurs at the bop. J. Dev. Entrep. 2013, 18, 1350015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E. Marketing in the social enterprise context: Is it entrepreneurial? Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2004, 7, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Eng, T.; Takeda, S. An Investigation of Marketing Capabilities and Social Enterprise Performance in the UK and Japan. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 267–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Osborne, S. Can marketing contribute to sustainable social enterprise? Soc. Enterp. J. 2015, 11, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Madill, J.; Chreim, S. Social enterprise dualities: Implications for social marketing. J. Soc. Mark. 2016, 6, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Managing Balance in Social Enterprise: Would For-Profit Activities Benefit Rather than Destroy Non-Profit Purpose? SSRN Electron. J. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madill, J.; Ziegler, R. Marketing social missions—Adopting social marketing for social entrepreneurship? A conceptual analysis and case study. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2012, 17, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.; Amran, A.; Yahya, S. Internal oriented resources and social enterprises’ performance: How can social enterprises help themselves before helping others? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, G.; Fleischer, M. The Processes of Technological Innovation; D.C. Heath & Company: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hujran, O.; Al-Lozi, E.; Al-Debei, M.; Maqableh, M. Challenges of Cloud Computing Adoption from the TOE Framework Perspective. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. 2018, 14, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayginer, C.; Ercan, T. Understanding determinants of cloud computing adoption using an integrated diffusion of innovation (DOI)-technological, organizational, and environmental (TOE) model. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2020, 8, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Lo, A.; Fong, L.; Law, R. Applying the Technology-Organization-Environment framework to explore ICT initial and continued adoption: An exploratory study of an independent hotel in Hong Kong. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, S.; Olatunji, S.; Chinedu-Eze, V.; Bello, A.; Ayeni, A.; Peter, F. Determinants of perceived information need for emerging ICT adoption. Bottom Line 2019, 32, 158–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, J. Assimilation of social media in local government: An examination of key drivers. Electron. Libr. 2017, 35, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, H.; Ukoha, O.; Emecheta, B. Using T-O-E theoretical framework to study the adoption of ERP solution. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2016, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschee, J. Social Entrepreneurship: The Promise and the Perils. In Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change; Nicholls, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Business Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chell, E. Social enterprise and entrepreneurship: Towards a convergent theory of the entrepreneurial process. Int. Small Bus. J. 2007, 25, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchikhi, H. A constructivist framework for understanding entrepreneurship performance. Organ. Stud. 1993, 14, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T. Promoting multi-paradigmatic cultural research in international business literature: An integrative complexity-based argument. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2016, 29, 599–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishers Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dudwick, N.; Kuehnast, K.; Jones, V.N.; Woolcock, M. Analysing Social Capital in Context: A Guide to Using Qualitative Methods; Data World Bank Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gopaldas, A. A Front-to-back Guide to Writing a Qualitative Research Article. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2016, 19, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, H. Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2018, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geer, J.G. What do open-ended questions measure? Public Opin. Q. 1988, 52, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, K.E. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Methodology; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.; Frey, J.H. The interview: From structured questions to negotiated text. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 645–672. [Google Scholar]

- Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.E.; Lancaster, G. The impact of digital books on marketing communications. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; van Manen, M. Phenomenology. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 614–619. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R. The Art of Case Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson Education Ltd.: Harlow, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. SAGE J. 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, M.; Ridley-Duff, R. Towards an Appreciation of Ethics in Social Enterprise Business Models. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 159, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukerjee, K.; Shaikh, A. Impact of customer orientation on word-of-mouth and cross-buying. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; Xiong, Q.; Wu, Y.; Tang, Y. The modelling and analysis of the word-of-mouth marketing. Phys. A. Stat. Mech. Appl. 2018, 493, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.A.; Kim, T. Predicting user response to sponsored advertising on social media via the technology acceptance model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukemiroglu, S.; Kara, A. Online word-of-mouth communication on social networking sites: An empirical study of Facebook users. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2015, 25, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, H. Effects of various characteristics of social commerce (s-commerce) on consumers’ trust and trust performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Zha, S. An exploratory investigation of social media adoption by small businesses. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2017, 18, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azemi, Y.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.E.; Lancaster, G. An exploration into the practice of online service failure and recovery strategies in the Balkans. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larasati, N. Technology Readiness and Technology Acceptance Model in New Technology Implementation Process in Low Technology SMEs. Int. J. Innov. Manag. Technol. 2017, 8, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.; Gardner, J. Aligning technology and institutional readiness: The adoption of innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 1229–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, G.; Roberts, M. Adoption of new information technologies in rural small businesses. Omega 1999, 27, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, J. An integrated model of information systems adoption in small businesses. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1999, 15, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tob-Ogu, A.; Kumar, N.; Cullen, J. ICT adoption in road freight transport in Nigeria—A case study of the petroleum downstream sector. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 131, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, M.; El-Kassar, A.; Tarhini, A. Impact of ICT-based innovations on organizational performance: The role of corporate entrepreneurship. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2017, 30, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.; Mustafa, S. SMEs and its role in economic and socio-economic development of Pakistan. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2017, 7, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, V.; Dow, K.; Chong, A.; Ngai, E. An examination of the long-term business value of investments in information technology. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 21, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera, C.; Iijima, J. The Role of IT and Organizational Capabilities on Digital Business Value. Pac. Asia J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2019, 11, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awiagah, R.; Kang, J.; Lim, J.I. Factors affecting e-commerce adoption among SMEs in Ghana. Inf. Dev. 2015, 32, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.A. Factors Affecting on Users’ Intentions toward 4G Mobile Services in Bangladesh. Asian Bus. Rev. 2019, 9, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, M.J.; Rousselière, D. Do hybrid organizational forms of the social economy have a greater chance of Surviving? An examination of the case of Montreal. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Non-Profit Organ. 2016, 27, 1894–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, P.; Mills, A. IT support for business processes in SMEs. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2011, 17, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, A.; Hossain, M.; Whiteside, N.; Mercieca, P. Social media and entrepreneurship research: A literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.; McColl, J. Contextual influences on social enterprise management in rural and urban communities. Local Econ. 2016, 31, 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, T.; Krishnan, M.S. Organizational adoption of web 2.0 technologies: An empirical analysis. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2012, 22, 301–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, S.; Saxton, G. Modeling the adoption and use of social media by nonprofit organizations. New Media Soc. 2012, 15, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, S. Media publicity and civil society: Nonprofit organizations, local newspapers, and the Internet in a Midwestern community. Mass Commun. Soc. 2010, 13, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napitupulu, D.; Syafrullah, M.; Rahim, R.; Abdullah, D.; Setiawan, M.I. Analysis of user readiness toward ICT usage at small medium enterprise in South Tangerang. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1007, 12–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Z.; Muhammad Arif, A. Strengthening access to finance for women-owned SMEs in developing countries. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2015, 34, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, B.; Chevers, D.; Williams, D. SMEs’ adoption of enterprise applications. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2013, 20, 735–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoko, H.; Ceric, A.; Huang, C. ICT adopting model of Chinese SMEs’. Int. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 8, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.; Xin, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhou, H.; Guo, J. A Preliminary Study on the Use of the ICTs in the Tourism Industry in China. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE/ACIS International Conference on Computer and Information Science, Sanya, China, 16–18 May 2011; Volume 1, pp. 373–376. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, A.Y.L.; Ooi, K.B.; Lin, B.S.; Raman, M. Factors affecting the adoption level of c-commerce: An empirical study. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2009, 50, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Hong, T.; Sabouri, M.; Zulkifli, N. Strategies for Successful Information Technology Adoption in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises. Information 2012, 3, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.; Quaddus, M. E-Services Adoption: Processes by Firms in Developing Nations; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kapurubandara, M.; Lawson, R. Availability of E-commerce Support for SMEs in Developing Countries. Int. J. Adv. ICT Emerg. Reg. 2009, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qu, W.; Oh, W.; Pinsonneault, A. The strategic value of IT insourcing: An IT-enabled business process perspective. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2010, 19, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, P.; Ho, M. How Opportunities Develop in Social Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J. Cracking the organizational challenge of pursuing joint social and financial goals: Social enterprise as a laboratory to understand hybrid organizing. Management 2018, 21, 1278–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, J.A.; Wry, T.; Zhao, E.Y. Funding Financial Inclusion: Institutional Logics and the Contextual Contingency of Funding for Microfinance Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 2103–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Haugh, H.; Chambers, L. Barriers to Social Enterprise Growth. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 1616–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumpi, D.; Magrizos, S.; Nicolopoulou, K. Virtuous circle: Human capital and human resource management in social enterprises. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 59, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaveli, N.; Geormas, K. Doing well and doing good: Exploring how strategic and market orientation impacts social enterprise performance. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Morley, A. Eight paradoxes of the social enterprise research agenda. Soc. Enterp. J. 2008, 4, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kumar Kar, A. Why do small and medium enterprises use social media marketing and what is the impact: Empirical insights from India. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahnil, M.I.; Marzuki, K.M.; Langgat, J.; Fabeil, N.F. Factors Influencing SMEs Adoption of Social Media Marketing. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamgbade, J.; Nawi, M.; Kamaruddeen, A.; Adeleke, A.; Salimon, M. Building sustainability in the construction industry through firm capabilities, technology and business innovativeness: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, M.; Hussain, H.; Ślusarczyk, B.; Jermsittiparsert, K. Industry 4.0: A Solution towards Technology Challenges of Sustainable Business Performance. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musawa, M.; Wahab, E. The adoption of EDI technology by Nigerian SMEs: A conceptual framework. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. 2012, 3, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, K.K.; Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P. Advances in Social Media Research: Past, Present and Future. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 20, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Islam, M.N.; Ozuem, W.; Bowen, G.; Willis, M.; Ng, R. An Empirical Investigation and Conceptual Model of Perceptions, Support, and Barriers to Marketing in Social Enterprises in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010345

Islam MN, Ozuem W, Bowen G, Willis M, Ng R. An Empirical Investigation and Conceptual Model of Perceptions, Support, and Barriers to Marketing in Social Enterprises in Bangladesh. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010345

Chicago/Turabian StyleIslam, MD Nazmul, Wilson Ozuem, Gordon Bowen, Michelle Willis, and Raye Ng. 2021. "An Empirical Investigation and Conceptual Model of Perceptions, Support, and Barriers to Marketing in Social Enterprises in Bangladesh" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010345

APA StyleIslam, M. N., Ozuem, W., Bowen, G., Willis, M., & Ng, R. (2021). An Empirical Investigation and Conceptual Model of Perceptions, Support, and Barriers to Marketing in Social Enterprises in Bangladesh. Sustainability, 13(1), 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010345