Sustainable Meat: Looking through the Eyes of Australian Consumers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Study Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.1.1. Stage 1: Online Survey

2.1.2. Stage 2: Eye-Tracking

2.1.3. Stage 3: In-Person Semi-Structured Interviews

2.2. Participants

| Standards | RSPCA Approved Farming Scheme 1 | Free-Range 2 | Free-Range 2 | Antibiotic-Free 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|  | |||

| Confinement in cages 4 | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Antibiotics are allowed under veterinary advice | YES | Depends on accreditation program | If antibiotics are required, meat may no longer be sold as free-range | YES |

| Growth promoting hormones are allowed 5 | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Birds have access to an outdoor area | NO Birds can be raised indoors; only applies when ‘free-range’ is written on the logo, | YES Birds must have easy access to an area on which to range | YES | N/A |

| Animals are fed only certified organic feedstuffs | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Animals are never fed grain or grain by-products | NO | NO | NO | N/A |

| On-farm assessment | YES | YES | YES | N/A |

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. Online Survey

2.3.2. Eye-Tracking

2.3.3. Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Perceptions of Sustainable Food Systems and Sustainable Chicken Meat Production Systems

3.2.1. Relative Importance of the Four Pillars of Sustainability to Food Systems

3.2.2. Importance of Sustainability When Purchasing Chicken Meat

3.2.3. Perceived Associations between Chicken Meat and Sustainability

“…well chicken doesn’t produce much methane because they don’t fart, I don’t think. I’ve never really considered it. Yeah, less sustainable. (...) So, the cows obviously produce more methane and then in terms of how they’re killed, I just think that it’s less sustainable, also because of how big they are. They obviously need more room and then they’re also grazing on farm or land. (...) I just think we’re over-fishing in a lot of places (…), you can tell because (…) my husband and my dad love crabbing and squidding and fishing, and over the years, even a short amount of time, there’s just less things in the ocean because people are just catching them all and they don’t have time to reproduce.”(Participant #9, Medium importance, female, 30 y, university degree, income Q5)

“So, I equate sustainable with ethical so like whether the welfare of the chicken is the primary concern.”(Participant #36, Low importance, female, 26 y, university degree, income Q4)

“To me, as I said, sustainability is more economic than anything else. It’s also got to be sustainable for the producers in Australia.”(Participant #53, High importance, female, 64 y, university degree, income Q4)

“I was thinking about environmental concerns more than my personal sustainability (laughs), so obviously buying a higher costing chicken breast is less sustainable (laughs) for me personally, if you could think about it like that. But I was thinking more of environmental concerns.”(Participant #62, High importance, female, 28 y, university degree, income Q2)

“…there’s a wholesaler in Melbourne that’s actually started promoting carbon neutral meat (for beef and lamb) and so they source meat from people that have actually measured their carbon footprint and then they’ve calculated the downstream carbon use and then offset the total which I think is excellent. I know if I was in the chicken industry I might not want to go too far down that track because at the moment the chicken industry has shown, because they talk about gross emissions, and gross emissions chicken meat is fantastic compared to beef and lamb but on cycle emissions, it doesn’t have any sequestering in it. It’s just out. Whereas the beef and lamb industry have huge sequestering that they can do.”(Participant #89, Medium importance, male, 47 y, university degree, income Q4)

3.3. Factors Consumers Use to Assess the Sustainability of Chicken Meat Products

3.4. Perceptions and Use of Sustainability Labels and Prices When Assessing the Sustainability of Chicken Meat Products

3.4.1. RSPCA Approved Farming Scheme

“I was thinking that they might be more sort of ‘earthy’ (laughing).”(Participant #79, Low importance, female, 42 y, university degree, income Q5)

“I would like to think something that’s bad for the chickens is also going to be bad for the environment. So environmentally I would say that you’re probably better off with that stamp.”(Participant #61, Low importance, male, 36 y, no university degree, income Q4)

“You can be like very nice in the RSPCA approved farming, but if you kill way too much then it’s not, and then it’s not sustainable.”(Participant #17, Low importance, male, 22 y, university degree, income Q1)

3.4.2. Free-Range

“I guess I just assume that if a farm is a free-range farm, then the people that are running that farm are more likely to be a bit more concerned with treating the animals better and maybe they’re concerned with sustainability and the environmental impact as well.”(Participant #16, High importance, male, 34 y, university degree, income Q5)

“I’d like to think that free-range isn’t going to be washing a ton of chemicals down the drain. Because if you’ve got a battery farm (…) you need to wash it down (…). You have diseases going through (…). I just don’t feel that battery farms and things give too much care into things like that.”(Participant #62, High importance, female, 28 y, university degree, income Q2)

“I guess if they’re also free-range that takes up land, and that land has to be farmed, so that’s clearing land for that.”(Participant #44, High importance, female, 32 y, university degree, income Q3)

“Sort of knowing that free-range is certainly way more exposed to fox predation (…) I think that’s probably it, and the potential to lose more chickens and makes them more expensive in the long run.”(Participant #27, Medium importance, female, 23 y, university degree, income Q1)

3.4.3. Antibiotic Free

“So, the antibiotics was an easy one to make a decision. It’s not sustainable to use antibiotics because the unintended long-term consequences are, to me, the most important thing in terms of the sustainability question. That’s what sustainability is all about, yes you can do this today, but what’s going to happen in 50 years’ time? Overuse of antibiotics is going to cause problems in 50 years’ time.”(Participant #89, Medium importance, male, 47 y, university degree, income Q4)

“I was probably thinking about the antibiotics staying in the environment, whether they actually dissipate or whether they’re still there the whole time. I don’t know enough about antibiotics, but that’s what I was thinking (…) It could be that never-ending circle, you eat the chicken meat and then it comes out in your excretions and then goes in the waterways and keeps on.”(Participant #34, High importance, female, 67 y, university degree, income Q5)

“With the sustainability, well, I guess antibiotic use in chicken just springs to mind a warehouse crammed full of chickens, that are all—because they don’t have any room or any sunlight or air or anything—they all need to be pumped full of antibiotics. So as a general rule, I don’t really want to support that model.”(Participant #62, High importance, female, 28 y, university degree, income Q2)

“If they use antibiotics, probably it helps a bit with the life or the quality of the chicken.”(Participant #18, Medium importance, female, 48 y, university degree, income Q4)

“I do remember thinking that if they raised them with antibiotics, it would actually be more sustainable. Again, related to output of production.”(Participant #70, Low importance, female, 47 y, university degree, income Q4)

“But I suppose if it doesn’t tell me directly on the label that it’s sustainable, then I look at other elements of the label that might suggest that as well as these qualities (...) and that they’re not full of antibiotics, then if you accept those things are true, then you could probably put into that bundle that the production of that meat that I’m looking at, was sustainable along the line. But that’s a supposition.”(Participant #80, Low importance, female, 63 y, university degree, income Q5)

“I don’t have strong opinions on antibiotics (laughing) and maybe I should and I don’t know what sustainable really means, yeah.”(Participant #79, Medium importance, female, 42 y, university degree, income Q5)

3.4.4. Price

“Probably just more money that goes into it—the chickens need more space, more farmland, more money, you know if they’re not using as many antibiotics then maybe more chickens die (…). I guess that if I saw that it was more expensive then I automatically assume that maybe it was more sustainable.”(Participant #25, Medium importance, male, 27 y, university degree, income Q1)

“Yes, one would imagine so because it would be more expensive to do the right thing by the environment than to just jam them into a cage and, you know, put all the entrails into the river so I’m paying for that.”(Participant #80, Low importance, female, 63 y, university degree, income Q5)

“To make it sustainable, I’d be looking at the price because I think nobody can, in general, the public can’t continue to pay $18 kilo (…) so that wouldn’t be sustainable long-term.”(Participant #53, High importance, female, 64 y, university degree, income Q4)

“I found myself leaning to price a fair bit, (…) because I wasn’t quite sure from a business perspective how you’re going to be able to sustain a business if you’re not selling a product and if there’s $21 chicken regardless of how many stamps you put on it versus a $9 sticker (…) you’re going to irrespective look at that $9 chicken over the $20 chicken.”(Participant #61, Low importance, male, 36 y, no university degree, income Q4)

“If I’m looking at sustainability only, then price is not important.”(Participant #36, Low importance, female, 26 y, university degree, income Q4)

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Implications

4.2. Strengths/Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Interview Guide

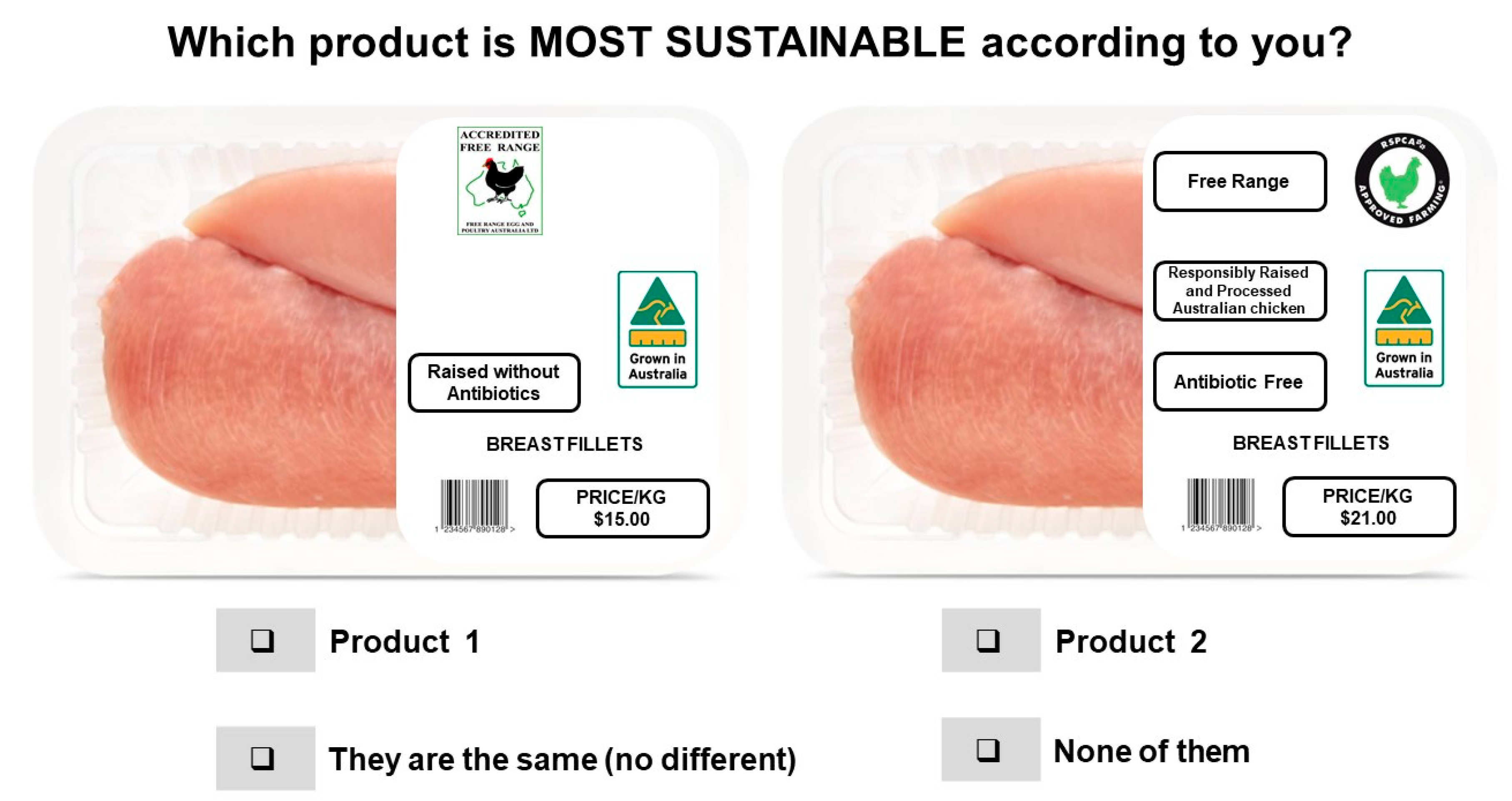

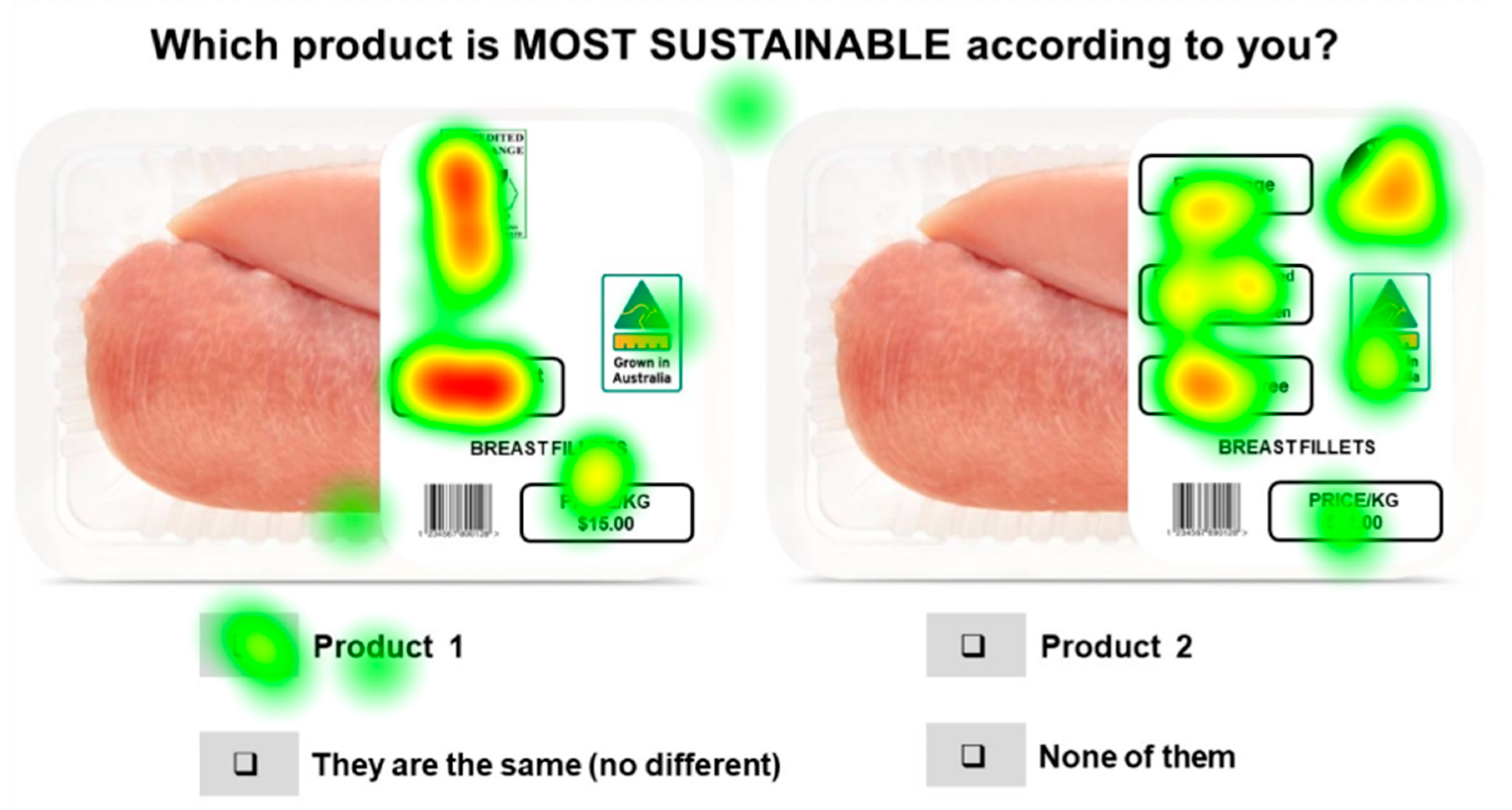

Questions for Sustainability Choice Sets

Appendix B

Sustainability Choice Sets Shown to Participants

References

- Adesogan, A.T.; Havelaar, A.H.; McKune, S.L.; Eilittä, M.; Dahl, G.E. Animal source foods: Sustainability problem or malnu-trition and sustainability solution? Perspective matters. Glob. Food Secur. 2019, 25, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.; Candel, J.; Davies, A.; de Vries, H.; Cristiane, D.; Dragović-Uzelac, V.; Hoel, A.H.; Holm, L.; Morone, P.; Penker, M.; et al. A Sustainable Food System for the European Union; Science Advice for Policy by European Academies: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Resare Sahlin, K.; Röös, E.; Gordon, L.J. ‘Less but better’ meat is a sustainability message in need of clarity. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Priorities for sustainable consumption policies. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Consumption; Edward Elgan Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, D.; Stadler, K.; Steen-Olsen, K.; Wood, R.; Vita, G.; Tukker, A.; Hertwich, E.G. Environmental Impact Assessment of Household Consumption. J. Ind. Ecol. 2016, 20, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Consumer in-store choice of suboptimal food to avoid food waste: The role of food category, communication and perception of quality dimensions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.; Waldrop, M.E.; Roosen, J. How does animal welfare taste? Combining sensory and choice experiments to evaluate willingness to pay for animal welfare pork. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.P.; Allen, L.H. Nutritional Importance of Animal Source Foods. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3932S–3935S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 515, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Silva, J. The Meat Crisis: The Ethical Dimensions of Animal Welfare, Climate Change, and Future Sustainability. In Sustainable Food Security in the Era of Local and Global Environmental Change; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Parodi, A.; Leip, A.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Slegers, P.M.; Ziegler, F.; Temme, E.H.M.; Herrero, M.; Tuomisto, H.; Valin, H.; van Middelaar, C.E.; et al. The potential of future foods for sustainable and healthy diets. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; Rolfe, J. Segmentation of Australian meat consumers on the basis of attitudes regarding farm animal welfare and the environmental impact of meat production. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2018, 58, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spencer, M.; Cienfuegos, C.; Guinard, J.-X. The Flexitarian Flip™ in university dining venues: Student and adult consumer acceptance of mixed dishes in which animal protein has been partially replaced with plant protein. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, N. Meeting the demand: An estimation of potential future greenhouse gas emissions from meat production. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 67, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberger, W.; Malek, L. Market Insights for Australia’s Chicken Meat Industry; Agrifutures Australia: Wagga Wagga, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Meat Consumption. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/fa290fd0-en (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Wiedemann, S.G.; Murphy, C.M.; McGahan, E.J.; Bonner, S.L.; Davis, R.J. Life Cycle Assessment of Four Southern Beef Supply Chains; Meat & Livestock Australia Ltd.: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann, S.; Mcgahan, E.J.; Poad, G. Using Life Cycle Assessment to Quantify the Environmental Impact of Chicken Meat Production; RIRDC: Canbera, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Janßen, D.; Langen, N. The bunch of sustainability labels—Do consumers differentiate? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J. Sustainability labelling schemes: The logic of their claims and their functions for stakeholders. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2003, 12, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loureiro, M.L.; McCluskey, J.J. Assessing consumer response to protected geographical identification labeling. Agribusiness 2000, 16, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Amstel, M.; Driessen, P.; Glasbergen, P. Eco-labeling and information asymmetry: A comparison of five eco-labels in the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, C.C.; Collins, L. Eco-labelling: Success or failure? Environmentalist 1997, 17, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, E.J.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Verbeke, W. Consumers’ valuation of sustainability labels on meat. Food Policy 2014, 49, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, B.; Rodrigues, H.; Nogueira, R.M.; Guimarães, K.R.L.S.L.D.Q.; Behrens, J.H. What about sustainability? Understanding consumers’ conceptual representations through free word association. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 44, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdiarmid, J.I.; Douglas, F.; Campbell, J. Eating like there’s no tomorrow: Public awareness of the environmental impact of food and reluctance to eat less meat as part of a sustainable diet. Appetite 2016, 96, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annunziata, A.; Scarpato, D. Factors affecting consumer attitudes towards food products with sustainable attributes. Agric. Econ. 2014, 60, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoek, A.; Pearson, D.; James, S.; Lawrence, M.; Friel, S. Shrinking the food-print: A qualitative study into consumer perceptions, experiences and attitudes towards healthy and environmentally friendly food behaviours. Appetite 2017, 108, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; Goddard, E. Committed vs. uncommitted meat eaters: Understanding willingness to change protein consumption. Appetite 2019, 138, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samant, S.S.; Seo, H.S. Effects of label understanding level on consumers’ visual attention toward sustainability and pro-cess-related label claims found on chicken meat products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 50, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, A.R.; Briley, D.; Wilson, B.J.; Raubenheimer, D.; Schlosberg, D.; McGreevy, P.D. The price of good welfare: Does informing consumers about what on-package labels mean for animal welfare influence their purchase intentions? Appetite 2020, 148, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Impact of sustainability perception on consumption of organic meat and meat substitutes. Appetite 2019, 132, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. Sustainability in the food sector: A consumer behaviour perspective. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2011, 2, 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J. Distinguishing meat reducers from unrestricted omnivores, vegetarians and vegans: A comprehensive comparison of Australian consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, E.J.; Hoefkens, C.; Verbeke, W. Healthy, sustainable and plant-based eating: Perceived (mis)match and involvement-based consumer segments as targets for future policy. Food Policy 2017, 69, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banović, M.; Chrysochou, P.; Grunert, K.G.; Rosa, P.J.; Gamito, P. The effect of fat content on visual attention and choice of red meat and differences across gender. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, G.; Zerweck, I.; Ehret, J.; Winter, S.S.; Stroebele-Benschop, N. The influence of the arrangement of different food images on participants’ attention: An experimental eye-tracking study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 62, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Chicken Meat Federation. Infographics. 2020. Available online: https://www.chicken.org.au/ (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Lilydale. Lilydale FAQ. 2020. Available online: https://lilydalefreerange.com.au/frequently-asked-questions (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Cervantes, H.M. Antibiotic-free poultry production: Is it sustainable? J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2015, 24, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSPCA Approved Farming Scheme. RSPCA Website. 2021. Available online: https://kb.rspca.org.au/ (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Free Range Accredited. FREPA Website. 2021. Available online: https://frepa.com.au/ (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Australian Chicken Meat Federation. Responsible Use of Antibiotics in the Australian Chicken Meat Industry. 2018. Available online: https://www.chicken.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/New_ACMF_Position-Statement_Antibiotics_180314F.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Australian Chicken Meat Federation. Meat Chickens and Cages. 2014. Available online: https://www.chicken.org.au/meat-chickens-and-cages/ (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Wedel, M.; Pieters, R. A review of eye-tracking research in marketing. In Review of Marketing Research; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, A. The Tobii I-VT Fixation Filter; Tobii Technology: Danderyd, Sweden, 2012; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L.; O’Connor, W.; Ormston, R. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2003; pp. 219–262. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, S.; White, M.; Wrieden, W.; Brown, H.; Stead, M.; Adams, J. Home food preparation practices, experiences and percep-tions: A qualitative interview study with photo-elicitation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malek, L.; Duffy, G.; Fowler, H.; Katzer, L. Use and understanding of labelling information when preparing infant formula: Evidence from interviews and eye tracking. Food Policy 2020, 93, 101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.C.; Cotgrave, A.J. Sustainable development: A qualitative inquiry into the current state of the UK construction industry. Struct. Surv. 2014, 32, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Education and Work, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics Canberra. 2017. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6227.0 (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 6523.0–Household income and wealth, Australia, 2013–2014. 2015. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6523.02015-16?OpenDocument (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 Census QuickStats: Australia. 2017. Available online: https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/036?opendocument (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Soini, K.; Dessein, J. Culture-Sustainability Relation: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T.D. Willingness to pay: Australian consumers and “on the farm” welfare. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2009, 12, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A. Italian consumer awareness of layer hens’ welfare standards: A cluster analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Pacelli, C.; Girolami, A.; Braghieri, A. Effect of Information About Animal Welfare on Consumer Willingness to Pay for Yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Musto, M.; Faraone, D.; Cellini, F. The Role of Cognitive Styles and Sociodemographic Characteristics in Consumer Perceptions and Attitudes Toward Nonhuman Animal Welfare. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2014, 17, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RSPCA. Approved Farming Scheme. Policy—Farm Animals General Principals. 2020. Available online: https://kb.rspca.org.au/knowledge-base/rspca-policy-b1-farm-animals-general-principles/ (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Leinonen, I.; Williams, A.G.; Wiseman, J.; Guy, J.; Kyriazakis, I. Predicting the environmental impacts of chicken systems in the United Kingdom through a life cycle assessment: Broiler production systems. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, J.; Taisch, M.; Mier, M.O. Influencing factors to facilitate sustainable consumption: From the experts’ viewpoints. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meise, J.N.; Rudolph, T.; Kenning, P.; Phillips, D.M. Feed them facts: Value perceptions and consumer use of sustainability-related product information. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbeke, W.; van Poucke, E.; Tuyttens, F.A. Do citizens and farmers interpret the concept of farm animal welfare differently? Livest. Sci. 2008, 116, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbeke, W. Public and Consumer Policies for Higher Welfare Food Products: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2013, 27, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Stewart, G.B.; Panzone, L.A.; Kyriazakis, I.; Frewer, L.J. A Systematic Review of Public Attitudes, Perceptions and Behaviours Towards Production Diseases Associated with Farm Animal Welfare. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Musto, M.; Cardinale, D.; Lucia, P.; Faraone, D. Creating Public Awareness of How Goats Are Reared and Milk Produced May Affect Consumer Acceptability. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2016, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musto, M.; Cardinale, D.; Lucia, P.; Faraone, D. Influence of Different Information Presentation Formats on Consumer Acceptability: The Case of Goat Milk Presented as Obtained from Different Rearing Systems. J. Sens. Stud. 2015, 30, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Ares, G.; Thøgersen, J.; Monteleone, E. A sense of sustainability?—How sensory consumer science can contribute to sustainable development of the food sector. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, L.; Delanchy, M.; Remaud, H.; Zepeda, L.; Gurviez, P. Consumers’ perceptions of individual and combined sustainable food labels: A UK pilot investigation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage 1 | Stages 2–3 | Australian Adult Population c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 87) | (n = 30) | ||

| Gender (females/males) | 56%/44% | 60%/40% | 51%/49% |

| Age, years | |||

| 18–24 years | 18% | 10% | 9% |

| 25–34 years | 26% | 27% | 19% |

| 35–44 years | 30% | 20% | 19% |

| 45–54 years | 15% | 20% | 19% |

| ≥55 years | 10% | 23% | 33% |

| Educational attainment (university degree) a | 74% | 80% | 31% |

| Household income quintiles b | |||

| ≤$35,000 | 12% | 10% | 20% |

| $35,001–$65,000 | 25% | 10% | 21% |

| $65,001–$105,000 | 21% | 23% | 19% |

| $105,001–$165,000 | 24% | 23% | 19% |

| >$165,000 | 18% | 33% | 21% |

| Pillar | Most Important Ranking (%) | Mean Rank Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 Participants (n = 87) | Stage 2–3 Participants (n = 30) | p-Value | Stage 1 Participants (n = 87) | Stage 2–3 Participants (n = 30) | p-Value | |

| Environmental | 75% | 69% | 0.835 | 3.61 | 3.55 | 1.000 |

| Economic | 20% | 21% | 0.959 | 2.54 | 2.48 | 0.717 |

| Social | 14% | 10% | 0.960 | 2.69 | 2.69 | 0.792 |

| Cultural | 2% | 0% | 0.574 | 1.48 | 1.31 | 0.285 |

| Level of Importance Placed on Sustainability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | Categories (Examples of the Most Relevant Type of Answers) | Low (n = 5) | Medium (n = 15) | High (n = 10) | Total (n = 30) | % (n = 30) |

| Environmental pillar/impact | Less use of water | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 20 |

| Reduced environmental impact | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 17 | |

| Less use of land/without destroying | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 10 | |

| Less production of waste/food waste | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Less food miles (shorter distance from farm to point of purchase) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Reduced carbon emissions caused by food production | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Using less packaging | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Reduced chemicals used in food production | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Animal Welfare | Animal welfare-friendly food production practices, indicated by specific labels (e.g., Free-range and RSPCA) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 27 |

| Animal welfare-friendly food production practices, no specific examples or labels cited | 2 | 2 | 4 | 13 | ||

| Antibiotics not being used improves animal welfare | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Don’t think animal welfare relates to sustainability | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Economic and Social pillars/impacts | Farmers maintaining production and profits | 3 | 3 | 6 | 20 | |

| Affordable for consumers | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 13 | |

| Fair working conditions and wages for food producers (e.g., Grown in Australia label, cited once) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 10 | ||

| Information on labels | Other examples cited: organic (n = 1), carbon neutral (n = 1) and sustainable (n = 1) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 10 | |

| Current labels don’t help to decide | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Don’t look for information on labels | 2 | 2 | 7 | |||

| Sustainability is not in the ‘back of the head’ while shopping | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Look for information on labels | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Antibiotic use | Antibiotics not being used improves animal welfare | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | |

| Antibiotics not being used improves the healthiness of foods | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Farmland conservation | Farmland conservation for multiple generations (will sustain for a long period of time) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 13 |

| Healthier for consumers | Healthier food products | 3 | 3 | 10 | ||

| Don’t know | Don’t know/No thoughts | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Labels/Claims (Areas of Interest) | Free-Range, Text | Free-Range, Logo | RSPCA Approved, Logo | Antibiotic Free, Text | Grown in Australia | Price | Cut | Meat Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of choice tasks in which label is shown | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Average % fixated each time label shown 1 | 90% c,d | 96% d | 71% b | 94% d | 94% d | 88% c,d | 76% b,c | 44% a |

| Average fixation count (number) | 3.12 ± 1.68 c,d | 4.03 ± 1.94 d | 2.20 ± 1.45 b,c | 3.94 ± 1.69 d | 2.14 ± 0.87 b,c | 2.01 ± 1.14 b | 1.14 ± 0.64 a,b | 0.38 ± 0.26 a |

| Average fixation duration (seconds) | 0.66 ± 0.40 d,e | 0.89 ± 0.46 e | 0.46 ± 0.30 c,d | 0.79 ± 0.33 e | 0.41 ± 0.17 b,c | 0.38 ± 0.23 b,c | 0.22 ± 0.13 a,b | 0.06 ± 0.05 a |

| Average visit count (number) | 2.36 ± 1.26 d | 2.33 ± 1.00 d | 1.30 ± 0.72 b,c | 2.53 ± 1.07 d | 1.63 ± 0.58 c | 1.43 ± 0.71 b,c | 0.94 ± 0.52 a,b | 0.34 ± 0.19 a |

| Average visit duration (seconds) | 0.69 ± 0.41 d,e | 0.95 ± 0.49 f | 0.50 ± 0.33 c,d | 0.83 ± 0.35 e,f | 0.43 ± 0.18 b,c | 0.40 ± 0.25 b,c | 0.22 ± 0.13 a,b | 0.06 ± 0.06 a |

| RSPCA Approved | Free-Range | Antibiotic Free | Price | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | Categories (Examples of the Most Relevant Type of Answers) | n | % (n = 30) | n | % (n = 30) | n | % (n = 30) | n | % (n = 30) |

| Related to sustainability in general | It is accredited/trusted, which influences the positive association with sustainability | 4 | 13 | 4 | 13 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 3 |

| Extra factor if combined with other labels | 3 | 10 | 4 | 13 | 10 | 33 | |||

| General positive association with sustainability/better than other labels | 1 | 3 | 6 | 20 | 3 | 10 | |||

| Not related to sustainability | Not related to sustainability and not trusted | 4 | 13 | 5 | 17 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Not trusted/believed the label has low standards | 3 | 10 | 2 | 7 | |||||

| Not related to sustainability, only with animal welfare | 7 | 23 | 3 | 10 | |||||

| Not related to sustainability because of the higher land requirements of this farming husbandry method when compared to non-free-range | 3 | 10 | 5 | 17 | |||||

| Not related/nothing to do with sustainability | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| Animal Welfare | Animal Welfare friendly production practices | 4 | 13 | 6 | 20 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Not in cages/more space | 2 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 7 | |||

| Happy animals | 3 | 10 | 7 | 23 | |||||

| Good feed | 1 | 3 | 5 | 17 | |||||

| Environmental pillar/impact | Perceived association between this label and environmental sustainability | 5 | 17 | 6 | 20 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Reduced use of chemicals and antibiotics | 3 | 10 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| Chickens are walking outdoors and fertilizing soil | 3 | 10 | 13 | 43 | |||||

| Healthier for consumers | Healthier products for consumers | 3 | 10 | 2 | 7 | ||||

| Economic and social pillars/impacts | Not sustainable because of its smaller scale | 2 | 7 | 2 | 7 | ||||

| Not sustainable because of the potential to lose chickens in the open field | 1 | 3 | 4 | 13 | |||||

| Farm is run properly and can continue in business | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| Don’t know | Don’t know/No thoughts | 5 | 17 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcez de Oliveira Padilha, L.; Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J. Sustainable Meat: Looking through the Eyes of Australian Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105398

Garcez de Oliveira Padilha L, Malek L, Umberger WJ. Sustainable Meat: Looking through the Eyes of Australian Consumers. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105398

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcez de Oliveira Padilha, Lívia, Lenka Malek, and Wendy J. Umberger. 2021. "Sustainable Meat: Looking through the Eyes of Australian Consumers" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105398

APA StyleGarcez de Oliveira Padilha, L., Malek, L., & Umberger, W. J. (2021). Sustainable Meat: Looking through the Eyes of Australian Consumers. Sustainability, 13(10), 5398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105398