Abstract

This study examines the relationship between psychological capital, social capital, and adaptive performance in China’s lodging industry. Recent research has revealed that the production attributes of internal social capital can explain adaptive performance, and that psychological capital affects the relationship attributes of social capital. This raises the question of whether social capital might mediate between psychological capital and adaptive performance. Therefore, this study examined data from a sample of 304 hotel employees in China, using internal social capital as a mediating variable. The results confirmed that psychological capital has a significant positive impact on adaptive performance. Social capital also plays a mediating role partially between psychological capital and adaptive performance. The findings of this study contribute to the theoretical framework of psychological capital and adaptive performance and provide a new approach to human resource management in the lodging industry and other dynamically competitive service industries.

1. Introduction

In a global economy that remains uncertain, the lodging industry faces an increasingly dynamic, complex, and unpredictable environment [1]. To operate successfully in dynamic environments, hotels must cultivate employees’ dynamic capabilities in light of these changes. Griffin, Neal, and Parker (2007) [2] pointed out that when a workplace is uncertain and unpredictable, role flexibility requirements are higher. “Flexibility refers to the capacity for change and adaptation over time” [3] (p. 9). In their cross-border roles, frontline hotel employees must not only meet the requirements of “internal adaptation”(Internal adaptation is employees’ cognitive attitude to changes in the internal environment, such as the organizational structure, post-change, flexibility of roles, and soft service) of their organizational objectives but also respond promptly to the dynamic “external adaptation”(External adaptation is employees’ cognitive attitude towards changes in the external environment, such as the market environment, the economic environment, the political environment, and technological innovation) environment. To promote organizational ambidexterity, frontline hotel employees must adapt to rapidly changing work situations.

Adaptive performance as a component of employee performance is employees’ ability to adapt to interpersonal relationships, acquire the knowledge and skills to adjust to a new environment, and solve problems creatively [4,5]. Adaptive performance is an extension and complement of traditional task and contextual performance and can solve the problems caused by traditional static performance management in a dynamic environment [6]. Unlike extra-role behaviors that employees willingly undertake to support others and benefit the organization [7], adaptive performance emphasizes the integration of person, task, organization, and environment. Organizational support [8], organizational climate (e.g., team learning and innovation) [9], transformative leadership [9], employment resources [10] and organizational structures (e.g., learning organization) [11] all have a major effect on employees’ adaptive performance.

The individual characteristics conducive to adaptive performance have been the focus of a large body of research, including the big five character traits [12], self-efficacy [1], cognitive ability [13], and experience and knowledge [14]. In contrast, the literature relied on the influence of adaptive performance of static factors and unchanging personality characteristics (e.g., the big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability). Several limitations, however, explain the dynamism of adaptive performance using static variables. Trait-based variables, such as personality, are permanent individual features that are difficult to alter [15]. Dynamic or changeable variables are more malleable because they can improve employees’ capacity for real intervention and are more promising intervention targets [16]. Psychological capital could measure both static and dynamic circumstances, according to Luthans and Youssef (2007) [17] and Kirrane et al. (2016) [15]. Detailed examinations of the synergies of psychological capital and adaptive performance would benefit hotels. Neither the effectiveness of psychological capital adaptability nor the development of adaptive performance in the hospitality field, however, has ever been examined.

Psychological capital is “one’s positive appraisal of circumstances and probability for success based on motivated effort and perseverance” [18] (p. 550)) that guides and stimulates individuals to reach their fullest potential [17]. Self-determination theory [19] holds that individuals strive to fulfill their psychological needs for autonomy [20], ability, and relationships [21]. In this sense, employees with large amounts of psychological capital will reach their potential and explore solutions, therefore improving their adaptive performance [22]. However, research on the relationship between psychological capital and adaptive performance is limited. Results from this study could rectify this deficiency.

Social mechanisms differ from the market and bureaucratic systems by countries. In China, the relational culture (guanxi) refers to the tight social networks that shape Chinese society. Guanxi includes not only the existing components, such as family relationships, classmate relationship, but also the instrumental attribute of the relationship. It is an implicit communication relationship based on mutual benefit and reciprocity [23,24]. Guanxi would have an emotional dimension as the number of contacts grows, which can compensate for each other regardless of gain and loss. From the perspective of cross-cultural research, western society is influenced by individualism, and people pursue self-worth. However, East Asian society is deeply influenced by Confucian guanxi culture [25], and pays more attention to the realization of self in a relationship to obtain peer support, trust, and personal identity [26].

The use of relational resources is a typical response when employees face unpredictable situations. Social capital consists of relational resources to help employees have a personal resource network [27]. Social capital can also foster employee social interaction and trust, thus improving their adaptability [10]. The theory of resource conservation [28,29] suggests that people strive to acquire, maintain, and preserve valued resources. People often use their relationship resources (social capital) to resolve crises and protect other resources when faced with uncertainty, problems, and pressure. Employees with large amounts of social capital will mobilize resources, explore solutions, and improve their adaptive performance. Ghitulescu (2013) [10] found that educational organizations, social ties and support are essential factors in the adaptive performance [30]. Thus, a main goal of this study is to determine whether social capital improves employees’ adaptive performance. Our results can compensate for the lack of prior research on the formation of adaptive performance mechanisms.

Another goal of this work is to investigate whether social capital has a mediating role. Psychological capital is a critical psychological resource for managing other resources [18]. Hobfoll (2002) [31] found that personal resources directly affect the cognition of relational resource and social capital is a type of relational resource in a social network [32]. Tamer, Dereli, and Saglam (2014) [33] pointed out that both the premise and the foundation of social capital formation are positive psychological capital development. Wu et al. (2012) [34] also proved that employees with large amounts of psychological capital have a greater sense of self-efficacy, actively interact with colleagues, and are more likely to gain the trust of the organization and colleagues, to acquire more social resources and promote the formation of social capital.

The increase in social capital has a direct impact on knowledge creation [35], innovation [36], reduced work stress [37], and social and cultural adaptability [38]. Social capital has the attribute of production, and the acquisition of relational resources will affect employees’ adaptive behavior. Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) [39] found that individuals with higher social capital have close ties with other organization members, trust each other, share a language and values, all of which make it are easier for them to integrate into the organization and promote the personal organization fit. According to self-determination theory [19] and conservation of resources theory [28,29], employees with large amounts of psychological capital can invest in social capital when facing a crisis or uncertainty, resolve the crisis with the help of relational resources, solve problems in creative ways, and therefore enhance their adaptive performance. As a result, this study determines whether social capital mediates the relationship between employees’ positive psychological resources and adaptive performance.

This study contributes to identify the effects of malleable and interventional capability on adaptive performance factors. There is a shortage of research in the lodging industry on the need for adaptive performance of employees’ duties as a service. The effect of static factors and unchangeable personality traits on adaptive performance has been emphasized in the literature; however, static variables cannot efficiently describe the dynamism of adaptive performance. Therefore, this study broadens our understanding of adaptive performance formation using psychological capital, a variable that can measure both static and dynamic situations. In addition, little research has been done on the formation of adaptive performance in Chinese relational culture. The research on the mediating role of social capital in psychological capital and adaptive performance makes up for the lack of previous literature and provides direction for further research in this field.

In summary, this study pursues the following three objectives:

- This study combines the theories of self-determination and the conservation of resources using frontline hotel employees as the research subjects to explore the impact of psychological capital on adaptive performance and its internal mechanism model.

- The effect of employees’ social capital on their adaptive performance.

- The role of social capital and its operational mechanism.

The results will provide theoretical guidance for hotels and other service companies to cultivate their employees’ potential and improve their adaptive performance.

The structure of this paper is as follows: The second section consists of a literature review and the formulation of hypotheses. This section discusses related concepts and details the hypothesis relationships between variables. The methodology section, which presents the questionnaire design and data collection, is the third section. The fourth section covers data analysis, procedure, process, and presentation of the results. The conclusion section discusses the findings, analyzes their theoretical and practical implications, and then proposes research limitations and possible research directions.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Psychological Capital and Adaptive Performance

Employees with psychological capital often have the internal motivation of self-improvement and growth [32], thus increasing employees’ attention and making them more receptive to new ideas. People with strong self-efficacy tend to learn actively, explore frontier knowledge, and constantly adjust and update their knowledge and skills according to the organization’s requirements and environment [17]. Previous studies have shown that psychological capital not only affects the attitudes of the employee [40] and promotes job performance [41] but also stimulates creativity and innovative behavior [42], turning personal potential into reality.

Positive emotions extend employees’ cognitive horizons and lead to more creative and exploratory thinking and action [43]. In contrast, negative emotions will interfere with their attention and efforts, which is not conducive to adaptive behaviors [44]. The positive psychological state which guides and stimulates individuals to reach their maximum potential is psychological capital [17]. Luthans (2002) [45] analyzed the literature on positive psychology and motivation to explore the factors affecting organizational members’ attitudes and behaviors and proposed the concept of psychological capital, which consists of self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience.

Psychological capital is the catalyst for widening one’s thoughts, which can significantly impact his/her creativity and innovative behavior in a positive way [46]. According to self-determination theory [19], to meet the needs for autonomy, ability, and relationships, employees with psychological capital will stimulate their creativity and innovative behavior [47], enhance autonomy motivation and explore solutions. Employees with more psychological capital have positive and proactive ways of influencing the perceptions of others and building good interpersonal relationships through active interaction and peer contact. When solving problems, employees with psychological capital can reduce the pressure [42,48], and use their resources and abilities to meet changing job demands and be better at their jobs [41].

The concept of job performance is constantly evolving. In the early literature, job performance was viewed in terms of task performance and contextual performance [49]. Task performance is limited to employees’ in-role activities. Contextual performance has no direct relationship to the task; instead, it promotes organizational progress, informal and spontaneous behavior, or organizational citizenship. In addition, task performance emphasizes the connection between people and tasks, while contextual performance emphasizes coordination among people, tasks, and organizations. However, both task performance and contextual performance apply only to a static and stable work environment. In response to a dynamic and changing environment, the concept of adaptive performance has thus emerged to compensate for the disadvantages of traditional performance.

Allworth and Hesketh (1997) [50] proposed the idea of adaptive performance which is the behavior of employees in response to changes in the work environment and in work needs. Since then, other scholars have extended the concept. London and Mone (1999) [51] defined adaptive performance in terms of personal proficiency in new knowledge learning or experience management. Murphy and Jackson (1999) [52] used a variety of role perspectives to explain adaptive behavior. Hesketh and Neal (1999) [53] defined adaptive performance as a way for individuals to cope with changes, concluding that just as environmental changes can be accommodated through learning, knowledge, and experience, adaptive behaviors can be dynamic, reactive, and endurance. Pulakos et al. (2000) [4] used the critical incident method to analyze 21 jobs, and identified eight dimensions of adaptive performance: interpersonal relationship adaptation, cultural adaptation, physical adaptation, learning new things, crisis management, work stress management, creative problem-solving, and uncertainty factor processing. Since then, the research on adaptive performance structural dimensions has been based on the eight-dimensional model proposed by Pulakos et al. (2000) [4]. Tao and Wang (2006) [54] argued that adaptive performance has four dimensions: interpersonal and cultural adaptation, creative problem-solving, stress and crisis management, and learning new things, based on Pulakos et al. (2000) [4] and Chinese cultural background. Pulakos et al. (2000) [4], however, noted differences in the types of adaptive behaviors required by various occupations.

As part of the emotionally intensive service industry, hotel guest service involves significant contact and value co-creation between employees and customers [55]. Employees’ psychological states and social interactions can significantly impact a hotel’s perceived service quality, employees’ performance and their sense of belonging [32]. Given the unique nature of the lodging industry, this study draws on the research of Pulakos et al. (2000) [4] and Tao and Wang (2006) [54] to define adaptive performance as employees’ ability to shape their environment to the demands of their work. In short, it is the ability for stress and crisis management, creative problem-solving, multicultural adaptability, and knowledge acquisition. Due to employee participation in service value co-creation, the lodging industry is focused on frontline hotel employees’ interaction with hotel guests and their responsiveness to customer needs. Accordingly, in a complex and dynamic environment, hotels need to find the best ways to leverage their employees’ dynamic skills to induce motivation, forge new paths, reinforce self-learning and respond subjectively to difficulties. Following Paek et al. (2015) [42] research framework, this study uses psychological capital as an endogenous positive psychological resource that can mobilize and stimulate individuals to respond to environmental changes. This leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Psychological capital has a significant positive impact on adaptive performance.

Hypothesis 1a.

Psychological capital has a significant positive impact on stress and crisis management.

Hypothesis 1b.

Psychological capital has a significant positive impact on creative problem-solving.

Hypothesis 1c.

Psychological capital has a significant positive impact on interpersonal and multicultural adaptability.

Hypothesis 1d.

Psychological capital has a significant positive impact on new knowledge acquisition.

2.2. Social Capital and Adaptive Performance

Social capital consists of the resources or abilities that individuals can mobilize through a network of social relationships in an organizational structure [56]. Hanifan (1916) [57] proposed the concept of social capital, but Bourdieu, Coleman, and Putnam contributed the most to the development of social capital theory. Bourdieu (1986) [58] was the first sociologist to analyze social capital, describing it as “a collection of actual or potential resources and social capital exists in the form of a network of relationships” (p. 248). Coleman (1988) [59] used rational choice theory to analyze social capital. He noted that social capital is not only a way to increase personal resources but also a principal resource for solving collective problems. Putnam (1993) [60] raised social capital from the individual to the societal level and introduced it into political science research.

According to the conservation of resources theory, people will maintain, protect, and invest in their resources to acquire more. The loss of resources is a threat, which can arise from uncertainty, crises, pressure, or difficulties in a dynamic environment. Therefore, in the face of difficulties, employees often draw on relational resources (social capital) to conserve their remaining resources. Employees with an abundance of social capital can interact, share information, increase trust and cohesiveness with other team members, share corporate goals, suppress dissatisfaction, and reduce stress so that they can work together to resolve the crisis and adapt to a new environment and new tasks.

Social capital exists in the network of social relations. The fewer relationships a person has in the face of pressure and crisis, the less social capital he or she has, and the lower the chance of solving problems. People with the most social capital have close relationships, trust others, and have a common language and values [39]. They are therefore more easily integrated into the organization, establish good interpersonal relationships, adapt to multiculturalism, and promote the fit between people and organizations.

Madjar (2005) [61] believed that creativity is the result of the independent thinking and action of employees and is stimulated in interaction and communication with other organizational members. To solve problems creatively, people with more social capital are more likely to communicate and cooperate with members of the organization to produce innovative ideas and actions. Kim et al. (2013) [56] show that more vital social interaction, social trust, and shared goals and visions are critical organizational resources that can enhance the generation of knowledge by the hotel staff and serve as the key mechanism for knowledge flow [62]. The sharing of knowledge among employees can promote their learning.

Furthermore, according to the job-demand resource model, resource acquisition will motivate employees and improve their work efficiency [63]. Employees can obtain intangible resources that help them develop through mutual trust, interpersonal communication, and relationship networks [62]. Abundant social capital helps employees to improve their collaboration. To complete a task, employees often need to communicate and cooperate with several departments; this kind of collaboration enhances adaptive performance. The links between social capital and adaptive performance are hypothesized as follows:

Hypothesis 2.

Social capital has a direct positive impact on adaptive performance.

Hypothesis 2a.

Social capital has a significant positive impact on stress and crisis management.

Hypothesis 2b.

Social capital has a significant positive impact on creative problem-solving.

Hypothesis 2c.

Social capital has a significant positive impact on interpersonal and multicultural adaptability.

Hypothesis 2d.

Social capital has a significant positive impact on new knowledge acquisition.

2.3. Psychological Capital and Social Capital

Hobfoll (2002) [31] noted that employees’ work engagement involves two kinds of resources: personal and relational. Personal resources are individual qualities such as optimism, self-confidence, and tenacity, which the organization can recognize. Relational resources are acquired through communicative interaction. Psychological capital is a positive resource, and social capital is a relational resource found in the social relationship network.

Luthans and Youssef (2004) [32] found that psychological capital and social capital are an organization’s primary competitive resources. Personal resources directly affect the perception of relational resources [31]. Tamer, Dereli, and Saglam (2014) [33] stated that psychological capital development is the premise and basis of social capital formation. It determines the degree to which social capital gains are acquired. Li et al. (2018) [64] explored mobilization from individual initiative to social capital from the perspective of individual psychology. The results showed that the mobilization of social capital is both restricted by social structure and influenced by the actors’ internal psychological characteristics.

Psychological traits affect individuals’ social capital and their behavior. Notably, employees with large amounts of psychological capital have a greater sense of self-efficacy, are more likely to trust interpersonal communication, gain the trust of organizations and colleagues, and thus acquire more social resources [34]. An abundance of psychological capital can enable employees to achieve their goals, build social networks, and communicate and interact with colleagues, therefore forming a friendly network of relationships [65]. Employees’ positive emotions also affect their accumulation of social resources [66]; when facing difficulties, they can be optimistic, seek solutions to problems, and thus gain recognition from organizations and colleagues to form and increase their social capital. The relationship between physical and social capital is hypothesized as follows:

Hypothesis 3.

Psychological capital has a direct positive impact on social capital.

2.4. The Mediating Effect of Social Capital

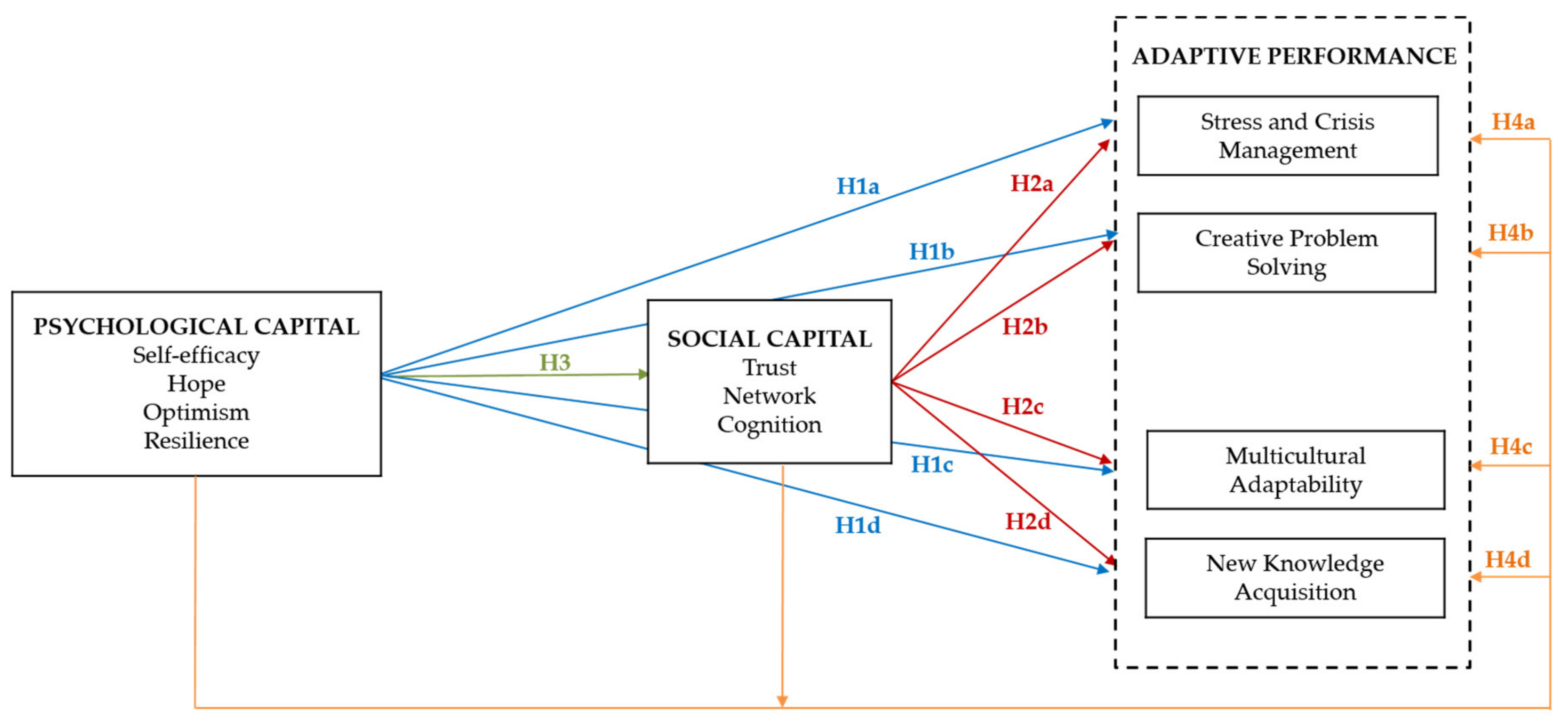

The increase in social capital has a direct positive impact on performance [67], knowledge creation [35], innovation [36] and learning behavior [68], reduced work stress [37] and social and cultural adaptability [38]. In a crisis, employees with psychological capital will explore solutions, acquire new knowledge and skills, and improve their adaptive performance. They can also invest in social capital, use relational resources to deal with the crisis, solve problems, and enhance their adaptive performance. People with large amounts of psychological capital are in a favorable position to accumulate, maintain and use scarce organizational resources. Based on this analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses. The research model is shown in Figure 1:

Hypothesis 4.

Social capital plays a mediating role between psychological capital and adaptive performance.

Hypothesis 4a.

Social capital plays a mediating role between psychological capital and stress and crisis management.

Hypothesis 4b.

Social capital plays a mediating role between psychological capital and creative problem-solving.

Hypothesis 4c.

Social capital plays a mediating role between psychological capital and interpersonal and multicultural adaptability.

Hypothesis 4d.

Social capital plays a mediating role between psychological capital and new knowledge acquisition.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Instrument Development

Adaptation of measurement items used in previous studies resulted in a preliminary questionnaire comprised of 56 Likert-scale statements (1–5 rating) and participant demographics, with 1 representing strongly disagree and 5 representing strongly agree. The translation/back-translation method was used to translate the scale [69]. We translated English into Chinese, and then two independent bilingual experts translated it back into English to ensure the translation quality. We pretested four hotel human resource directors and more than 50 frontline hotel employees to evaluate the preliminary instrument’s readiness for use in this study. Based on the pretest’s findings and suggestions, slight modifications to wording were made to ensure that employees would understand the instruction and terminology.

The 24-item psychological capital scale was adapted from the psychological capital questionnaire developed by Luthans and Youssef (2007) [17], which classifies mental capital into four subsections with six questions each: self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience. The 11-item social capital scale, which drew from the scale that Chow and Chan (2008) [62] developed, was divided into three subsections of trust (three items), network (five items), and cognition (three items). The 21-item adaptive performance scale draws on the scales of Pulakos et al. (2000) [4], along with Tao and Wang’s (2006) [54] research. Taking the nature of the lodging industry into account, we divided adaptive performance into four subsections: stress and crisis management (five items), creative problem-solving (four items), interpersonal and multicultural adaptability (six items), new knowledge acquisition (six items).

3.2. Data Collection

We used the purposive sampling of nonrandom sampling methods to select four-star or five-star hotels in representative provinces and cities. The samples were from Beijing, Guangdong (Shenzhen, Guangzhou), Jiangsu (Nanjing, Suzhou, Changzhou), Shandong (Ji’nan, Qingdao, Yantai), Shanghai, Zhejiang (Hangzhou, Ningbo). These provinces are economically developed, with high per capita income and more scenic spots in the eastern coastal areas, which are well represented. A total of 600 questionnaires were distributed in four- and five-star hotels in six provinces in China. All the respondents had worked in the hotel for more than six months. The data were collected from June 2018 to July 2018, using a combination of online and offline research methods. Offline data were gathered mainly through contact with each hotel’s human resource management, who gave permission and helped obtain the data from participants. All paper questionnaires were sealed in envelopes to keep employees’ information confidential. If the respondents could not fill in the self-administered questionnaire at work, they could complete a WeChat online questionnaire.

To test the causal relationship among psychological capital, social capital and frontline hotel employees’ adaptive performance and reduce the potential for standard method variance, data were collected twice at a two-week interval. The first survey collected psychological capital data and demographic information of frontline hotel employees; the second collected data on social capital and adaptive performance. To match the data from the two surveys, the samples were numbered using employees’ identification numbers.

3.3. Data Screening

A total of 600 questionnaires were distributed, of which 429 were returned. After discarding cases with incomplete responses, 304 questionnaires out of 429 were usable for data analysis, resulting in a 70.86% response rate. In the sample distribution of valid questionnaires (Table 1), the number of women employed in the lodging industry was relatively high (62.5%); the largest percentages of respondents were 20–29 years old (50.7%), and 30–39 years old (36.2%). Respondents with a university degree made up the highest proportion (74.3%), followed by those with a junior college degree (19.2%). The average number of years working at a hotel was 3–5 years (41.8%), followed by more than five years (33.2%).

Table 1.

The summary of the samples (N = 304).

4. Statistical Analyses and Findings

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

To verify the necessary degree of fit for the sample measuring factors, confirmatory factor analysis was done using analysis of a moment structures software (AMOS®). Next, to confirm the intrinsic degree of fit among the measured factors, the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) from the latent variables were used to judge convergent validity. To verify the discriminant validity among the measurement factors, the divergence was judged by calculating whether [∅ ± 2 × S.E.] contained 1 [70]. To ascertain the appropriateness of the degree fit for the whole model, through AMOS, the covariance structure was used to analyze the structural model. Finally, bootstrapping was used to judge and confirm whether the mediating effect of the mediator variable was complete or partial [71].

Cronbach’s α coefficient value was used to assess the reliability of the adopted scales, each scale was independently tested for Cronbach’s alpha value, the value of 0.70 or above was considered to be the acceptability threshold for the current research [72]. Results indicated Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.70 to 0.90 suggesting acceptable reliability for all adopted scales. Harman’s single-factor test was applied to determine if standard method variance was an issue. Therefore, all items related to hope, optimism, resilience, self-efficacy, trust, network, cognition, stress and crisis management, creative problem-solving, cultural adaptation, and new knowledge learning ability were loaded on a single factor through exploratory factor analysis. The single factor explained only 35% of the variance. This result indicated that standard method variance was not a critical concern.

Using AMOS to perform a confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) was lower than the estimated standard value, so some questions were removed using modification indices. The questions removed were as follows: six from psychological capital (one on self-efficacy, one on hope, two on optimism, two on resilience), three from social capital (two on network, one on cognition), and two from adaptive performance (two on multicultural adaptability). The confirmatory factor fitness index of the remaining 45 questions was good (Appendix A). Table 2 shows the results of the confirmatory factor analysis. The results were found to be X2 = 67.794, df = 38, p = 0.000. GFI = 0.960, AGFI = 0.930, CFI = 0.987, IFI = 0.988, RMSEA = 0.051 conformed to the standard value (GFI, AGFI, CFI, IFI > 0.9, RMSEA = 0.05 − 0.08), so the measurement model was suitable.

Table 2.

Results of the composite reliability validity analysis.

Table 2 shows that the composite reliability and the AVE were higher than the standard values (CR was 0.7 or more, AVE was 0.5 or more); thus, there was good convergent validity among the measurement factors. The discriminant validity among factors was judged by calculating whether the [∅ ± 2 × S.E.] value contained the number 1 [70]. The correlation index “±” (plus sign and minus sign) between the two latent variables was multiplied by the standard error, and the value between the sum and the difference was compared. If the difference index does not contain the number 1, the difference is sufficient. Furthermore, if the difference index contains the number 1, it means that each factor did not have discriminant validity. Table 3 shows a degree of discriminating validity for each factor. Furthermore, the confirmatory factor analysis of the six variables indicated that the six-factor model fits the data considerably better than any of the alternatives (Table 4). The findings of further round analyses showed that the six variables were independent and had good validity of discrimination.

Table 3.

Results of the discriminant validity analysis.

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

4.2. Path Analysis

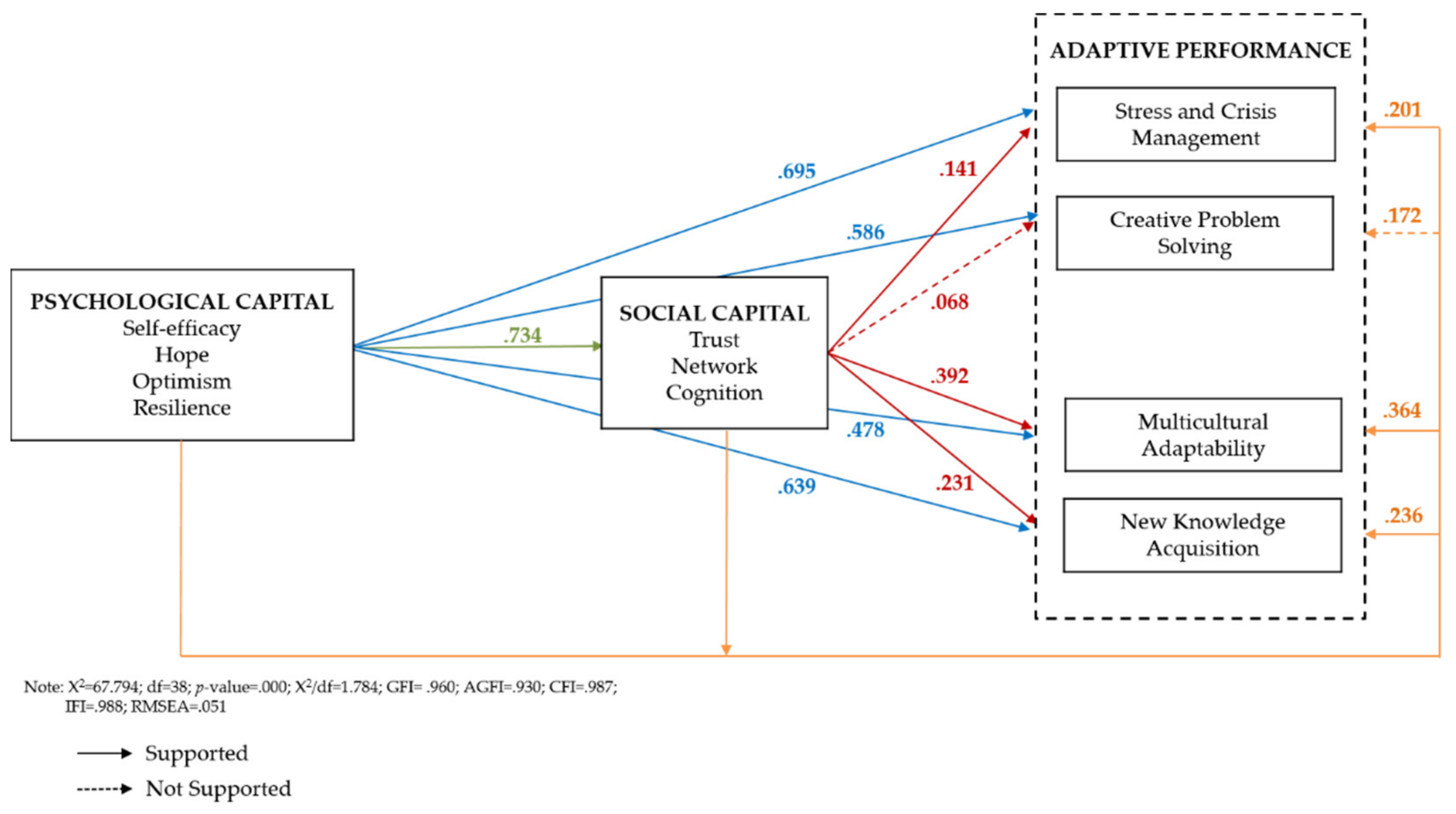

To verify the relationship among psychological capital, social capital, crisis management, creative problem-solving, multicultural adaptability, and new knowledge and skill acquisition, the AMOS covariance structure was used to analyze its model structure. The maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the model, and standardized estimation, squared multiple correlations, indirect effect, direct effect and total effects, critical ratio for differences, and modification indices were analyzed. The results of the analysis are shown in Figure 2, X2 = 67.794, df = 38, p = 0.000. GFI = 0.960, AGFI = 0.930, CFI = 0.987, IFI = 0.988, RMSEA = 0.051 met the standard value (GFI, AGFI, CFI, IFI > 0.9, RMSEA = 0.05~0.08), so the model structure was found to be appropriate and reasonable.

Figure 2.

Path analysis results.

The results of the complete path analysis are shown in Table 5. Psychological capital was shown to have a positive impact on stress and crisis management (β = 0.695, p < 0.001), creative problem-solving (β = 0.586, p < 0.001), multicultural adaptability (β = 0.478, p < 0.001), and new knowledge acquisition (β = 0.639, p < 0.001), with significant effects among them. Psychological capital had the most significant impact coefficient on stress and crisis management, consistent with Hypothesis 1. In addition, social capital had a positive influence on stress and crisis management (β = 0.141, p < 0.01), multicultural adaptability (β = 0.392, p < 0.001), and new knowledge acquisition (β = 0.231, p < 0.05), and the effect was significant. However, social capital had no significant effect on creative problem-solving (β = 0.068, p = 0.293 > 0.05). Therefore, except for Hypothesis 2b, all other hypotheses 2 were supported.

Table 5.

Results of the path analysis.

Psychological capital was also found to have a positive impact on social capital (β = 0.734, p < 0.001), and the effect was significant. In terms of whether social capital had a mediating effect between the dimensions of psychological capital and adaptive performance, we know from bootstrapping that psychological capital had an indirect and insignificant influence on the dimensions of adaptive performance through social capital, except for creative problem-solving.

The mediating effect could be full or partial. To confirm which intermediary the social capital belonged to, we had to confirm the direct and indirect relationship between psychological capital and the dimensions of adaptive performance. If the direct impact of psychological capital on adaptive performance was not significant, but the indirect relationship was, we concluded that mean social capital plays a full intermediary role. In contrast, if psychological capital had a significant effect on the dimensions of adaptive performance, and the effect of indirect relations was also significant, it would mean that social capital plays a mediating role partially. Table 6 shows the results after bootstrapping verification.

Table 6.

The mediating effect analysis results.

We found a positive and significant correlation between the dimensions of psychological capital and adaptive performance. In addition, psychological capital had a significant effect on the indirect relationship between the dimensions of adaptive performance, except for creative problem-solving (where the indirect effect was not significant). In summary, psychological capital not only directly affects crisis management, creative problem-solving, cultural adaptability, and new knowledge skills but also indirectly affects crisis management, cultural adaptability, and acquisition of new knowledge skills through social capital. Therefore, social capital plays a partial intermediary role between psychological capital and adaptive performance.

5. Conclusions, Discussion and Implications

As the internal and external environment of the lodging industry becomes more complex, the adaptability of employees becomes critical, and adaptive performance becomes an essential part of the performance appraisal. Although adaptive performance has been discussed at the personal [12] and organizational levels [8], the development of adaptive performance is a new topic of study and has been under-explored in the hospitality sector. Results from this study demonstrate the effects of malleable and interventional capability on adaptive performance factors. Specifically, this study examines the impact of employees’ psychological capital on adaptive performance. The results support the research hypothesis that psychological capital has a positive effect on employees’ adaptive performance. In terms of the impact of social capital on adaptive performance, except for creative problem-solving, employees’ internal social capital stock positively impacts adaptive performance. Moreover, the results show that psychological capital can promote social capital. The paper also explores the formation mechanism of adaptive performance, i.e., the mediating role of social capital between psychological capital and adaptive performance. The results show that social capital can mediate the relationship between psychological capital and adaptive performance. After empirical data analysis, we summarize the main contributions of this study.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings contribute to the understanding of how to mobilize and activate psychological resources. Frontline hotel employees are different from employees in other industries. Their independence, coordination and dynamics require them to have positive psychological capital to realize their potential, enhance their autonomy, mobilize social capital, coordinate internal and peripheral relationships, respond to a variety of dynamic changes, and improve their adaptive performance. Previous literature examined the relationship between psychological capital and historical performance, but not the relationship between psychological capital and adaptive performance. The findings confirm previous evidence that psychological capital is positively associated with career adaptability [41]. When employees possess psychological capital, they will be more engaged in their work [40,42,73]. If the organization can cultivate personal psychological capital in a targeted way, employees will be prepared to deal with emergencies and stress and solve problems. Even if they are in a troubling situation, they can still solve problems, therefore improving their adaptive performance. The more psychological capital employees have, the more positive their emotions, which will strengthen their vitality and concentration at work, and thus improve their adaptive performance.

This paper also proves the return mechanism of social capital [62,64] and confirms the positive impact of social capital on job performance found by Liu (2017) [67]. The results of this study complement and verify the positive, stimulating effect of social capital on adaptive performance and expand the theory of social capital and job performance. Employees’ internal social capital stock has a significant positive impact on stress and crisis management, interpersonal relationships, multicultural adaptability, and the acquisition of new knowledge and skills in adaptive performance. Social capital is a personal relational resource, according to the conservation of resources theory [42], and the acquisition of relational resources helps to improve employees’ ability to solve problems, reduce work stress [37], and improve social and cultural adaptability [38]. In Chinese relational culture, the production property of social capital is substantial. To complete their tasks, hotel employees often need to communicate and collaborate effectively with their supervisors, colleagues, or subordinates. A rich store of social capital helps employees gain more support. The effect of internal social capital on creative problem-solving was insignificant. One explanation is that individuals’ social capital production strengthens their problem-solving ability but may weaken their creativity.

Furthermore, when psychological capital affects adaptive performance, social capital plays a mediating role. In the past, the study of social capital paid too much attention to its production attributes at the expense of its relationship attributes; that is to say, it paid more attention to the return mechanism of social capital and ignored its intermediate mobilization process [64]. The results presented in this paper explore the mobilization mechanism of social capital in relation to individual psychological capital, and find that the psychological capital affects the relationship property of internal social capital mobilization. The production attribute of social capital can predict employees’ adaptive performance. If employees have positive psychological capital, their social capital will increase, which will then stimulate their proactive motivation [74], help them to recognize relational resources, enhance their social relations, improve their ability to solve problems in a dynamic environment, reduce the sources of pressure at work, and improve their adaptive performance.

5.2. Practical Implications

Based on the research results, the following management recommendations are suggested for hotel managers and other service industries that have intensive contact with customers.

Positive psychological capital can stimulate employees’ potential, enable them to handle stress, solve problems, acquire knowledge and skills, adapt to multi-contextual, multicultural interactions, and improve their adaptive performance. Functioning in a cross-border role in direct contact with customers, hotel employees need numerous capabilities. By cultivating their psychological capital, employees can limit their occupational fatigue and stress, stimulate positive energy and overcome negative emotions, mobilize their inner potential, stimulate their creativity, improve their ability to cope with environmental changes and enhance their adaptive performance. We can conclude that psychological capital is a fundamental resource for coping with crisis and stress and compensates for the consumption of psychological resources.

Hotel managers should break free of the traditional mindset, pay attention to the psychological state of employees, and try to build a positive organizational culture, encourage employees’ positive behaviors, and tap into their internal motivation. Innovative management and targeted interventions such as regular investigation and study of the psychological state of employees, the development of psychological training programs, the introduction of a mentoring system, and the strengthening of psychological capital knowledge education and training will help build employees’ psychological capital. When recruiting frontline employees, hiring managers should pay attention to applicants’ psychological state, and psychological capital should be used to ensure the hiring of employees with an abundance of psychological capital. Hotel managers must be cognizant of their employees’ psychological problems, help them cope with complex and ever-changing environments, and enhance their ability to handle setbacks and avoid trouble. It is also advisable to include employees in decision-making to enhance their internal identity and adaptability. Employees are responsible for maintaining a positive psychological state, accumulating successes, encouraging themselves, and increasing their stock of psychological capital.

Another major finding is that if psychological capital is an internal driving force, then social capital is the external influence factor in employees’ adaptive performance. The consumption of hotel products and services requires interdepartmental cooperation. Good interpersonal interaction and trust among employees can promote hotel service quality. In this process, internal social capital is important. On the one hand, hotels should cultivate the relationship attributes of social capital, provide platforms for employee communication, encourage exchanges among departments, create a relaxed atmosphere for communication, strengthen communication and interaction between leaders and employees, and establish open and transparent communication channels. They should also introduce a mentoring system, so that new employees receive help from more experienced ones. A workshop system should be established to promote exchanges and interactions among colleagues, increase trust among colleagues and their understanding of the companies, therefore improving employees’ adaptive performance. On the other hand, internal factors determine external ones; therefore, hotels should focus on both internal and external training. When selecting and promoting employees, organizations should prioritize psychological capital and employees’ ability to mobilize social capital.

Human resources flexibility is the primary factor in the development of competitiveness and innovation [75]. These findings could allow human resource practitioners and hotel managers to use psychological capital to nurture good human resource flexibility in their system for better performance of both employees and the organization. As such, psychological and social capital should be considered for human resources development, and the most capable should be selected to cultivate the hotel’s ability to adapt to dynamic environments.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. The reactions of psychological capital, social capital, and adaptive performance come from frontline employees. This may lead to an inflated relationship. To compensate for this limitation, future studies should try to replicate our findings using adaptive performance ratings by supervisors. In addition, we cannot exclude the influence of social capital on psychological capital. In future research, the synergy of psychological capital and social capital should be examined. Finally, to reduce the variance of the standard method, although we have adopted measures such as “reducing situational stress,” follow-up studies should use the standard method of measurement of social desirability. An independent sample t-test should also be conducted in a self-directed questionnaire and an online questionnaire to check whether there is a significant difference between the two. Moreover, although we have identified development factors that affect adaptive performance, our findings cannot be readily extended to a wider range of research. Further research is needed, for instance, to compare the individual adaptive performance of different industries, and whether psychological capital and social capital play the same roles in each. In addition, this research emphasizes adaptive performance at the individual level. In the future, scholars can study professional adaptability, team adaptability, and the like.

With the development of adaptive performance research, additional experimental studies and interventions are needed to improve individual adaptability. For example, a meta-analysis could compare the impact of predictors on adaptive performance. In addition, future research could explore the adaptive performance of employees using the event system theory [76]. In the end, the use of variables in second-order confirmatory factor analysis (second-order CFA) may cause errors in linear consistency. Other analytical methods can be used in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing—original draft, C.-Y.L.; Writing—review & editing, Visualization, C.-H.T.; Supervision, M.-H.C.; Data Collection, J.-L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received financial support from Jiangsu Education Department Project (grant number: 2019SJA1756) and Jiangsu Social Science Fund (grant number: 20GLC002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Research Measures

| Factors (No. of items) | Measures | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| Psychological Capital | ||

| Self-efficacy (5) | I feel confident analyzing a long-term problem to find a solution. | 0.760 |

| I feel confident contributing to discussions about my hotel’s strategy. | ||

| I feel confident helping to set targets/goals in my work area. | ||

| I feel confident contacting people outside my hotel (e.g., customers) to discuss problems. | ||

| I feel confident presenting information to a group of colleagues. | ||

| Hope (5) | If I find myself in a jam at work, I can think of many ways to get out of it. | 0.730 |

| There are lots of ways around any problem that I am facing now. | ||

| Right now I see myself as being pretty successful at work. | ||

| I can think of many ways to reach my current goals. | ||

| At this time, I am meeting the work goals I have set for myself. | ||

| Optimism (4) | When things are uncertain for me at work I usually expect the best. | 0.700 |

| If I have a problem in my work, I think it is temporary and can be solved. | ||

| I always look on the bright side of things regarding my job. | ||

| In my current job, things are developing as I expected. | ||

| Resilience (4) | I usually manage difficulties one way or another at work. | 0.710 |

| I can be “on my own,” so to speak, at work if I have to. | ||

| I usually take stressful things at work in my stride. | ||

| I feel I can handle many things at a time at my job. |

| Social Capital | ||

| Trust (3) | I know my organizational members will always try and help me out if I get into difficulties. | 0.700 |

| I can always trust my organizational members to lend me a hand if I need it. | ||

| I can always rely on my organizational members to make my job easier. | ||

| Network (3) | At work, I can keep close communication with other colleagues. | 0.710 |

| At work, I can easily contact and communicate with other departments. | ||

| I always hold a lengthy discussion with my organizational members. | ||

| Cognition (2) | My colleagues and I always agree on what is important at work. | 0.700 |

| My colleagues and I always share the same ambitions and vision at work. |

| Adaptive Performance | ||

| Stress and crisis management (5) | When dealing with urgent problems, I usually think clearly and have clear priorities. | 0.700 |

| I quickly take effective action to solve the problem. | ||

| I stay calm under circumstances where I have to take many decisions at the same time. | ||

| I keep focused on the situation to react quickly. | ||

| I examine available options and their implications to choose the best solution. | ||

| Creative problem-solving (4) | When complex problems arise, I always have innovative methods. | 0.700 |

| I rely on a wide variety of information to find an innovative solution to the problem. | ||

| I try to avoid following established ways of addressing problems to find an innovative solution. | ||

| My colleagues take advice from me for generating new ideas and solutions. | ||

| Interpersonal relationships and multicultural adaptability (4) | I can modify my behavior to adapt to other cultures and customs. | 0.710 |

| I always develop positive relationships with the people I interact with when doing my job because it helps me perform better. | ||

| I actively understand the organizational climate and direction of development of the company. | ||

| I try to consider others’ viewpoints to better interact with them. | ||

| New knowledge and technology learning ability (6) | I search for innovations in my job so as to improve work methods. | 0.750 |

| I learn new knowledge or skills quickly. | ||

| I can apply my new knowledge to my work. | ||

| I take actions (within or outside the company) to keep my skills up to date. | ||

| I can quickly adapt to work procedures or work content that I have not been exposed to before. | ||

| I always take action to correct my shortcomings in my work. |

References

- Pedro, M.Q.; Ricardo, V.; Nicole, E.; Luís, C. Employee adaptive performance and job satisfaction during organizational crisis: The role of self-leadership. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psy. 2019, 28, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent context. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, J.B.; Way, S.A.; Tews, M.J. HR in the hospitality industry: Strategic frameworks and priorities. In Handbook of Hospitality Human Resources Management; Tesone, D.V., Ed.; Elsevier Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pulakos, E.D.; Arad, S.; Donovan, M.A. Adaptability in the work place: Development of a taxonomy of adaptability performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakos, E.D.; Schmitt, N.; Dorsey, D.W.; Arad, S.; Berman, W.C.; Hedge, J.W. Predicting adaptive performance: Further tests of a model of adaptability. Hum. Perform. 2002, 15, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.K.; Witt, L.A.; Vera, D. When does adaptive performance lead to higher task performance? J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 910–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyne, L.V.; Cummings, L.L.; Parks, J.M.L. Extra-role behaviors: In pursuit of construct and definitional clarity. Res. Organ. Behav. 1995, 17, 215–285. [Google Scholar]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Lorinkova, N.M.; Van Dyne, L. Employees’ social context and hange-oriented citizenship: A meta-analysis of leader, coworker, and organizational influences. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 291–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonnier-Voirin, A.; Akremi, A.E.; Vandenberghe, C. A multilevel model of transformational leadership and adaptive performance and the moderating role of climate for innovation. Group Organ. Manag. 2010, 35, 699–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghitulescu, B.E. Making change happen the impact of work context on adaptive and proactive behaviors. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2013, 49, 206–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanten, P.; Kanten, S.; Gurlek, M. The effects of organizational structures and learning organization on job embeddedness and individual adaptive performance. Proc. Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.I.; Ryan, A.M.; Zabel, K.L. Personality and adaptive performance at work: A meta-analytic investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 91, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, D. Predicting real-time adaptive performance in a dynamic decision-making context. J. Manag. Organ. 2014, 20, 715–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.A.; Zou, S.; Vorhies, D.W.; Katsikeas, C.S. Experiential and informational knowledge, architectural marketing capabilities, and the adaptive performance of export ventures: A cross-national study. Decis. Sci. 2003, 34, 287–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirrane, M.; Lennon, M.; O’Connor, C.; Fu, N. Linking perceived management support with employees’ readiness for change: The mediating role of psychological capital. J. Chang. Manag. 2016, 17, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M. Employees’ attitudes toward organizational change: A literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 50, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Emerging positive organizational behavior. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-regulation and the problem of human autonomy: Does psychology need choice, self-determination, and will? J. Pers. 2006, 74, 1557–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baard, P.P.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 2045–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Derks, D. Who takes the lead? A multi-source diary study on leadership, work engagement and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 37, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, K.R.; Pearce, J.L. Guanxi: Connections as substitutes for formal institutional support. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1641–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.M. Gifts, Favors and Banquets: The Art of Social Relationships in China; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, T.; Morris, M.W.; Chiu, C.Y.; Hong, Y.Y. Culture and the construal of agency: Attribution to individual versus group dispositions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.F.; Xie, T. True self in east and west from Guanxi perspective. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 29, 894–905. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Employee voice behavior: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Park, S.Y. Employee adaptive performance and its antecedents: Review and synthesis. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2019, 18, 294–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamer, I.; Dereli, B.; Saglam, M. Unorthodox forms of capital in organizations: Positive psychological capital, intellectual capital and social capital. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Xie, X.X. The Chinese indigenous psychological capital and career well-beling. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2012, 44, 1349–1370. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.H.; Lee, T. Promoting entrepreneurial orientation through the accumulation of social capital, and knowledge management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.W. Making innovation happen through building social capital and scanning environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 56, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. Social capital and perceived stress: The role of social context. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 250, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.M. The relationship between social capital, acculturative stress and depressive symptoms in multicultural adolescents: Verification using multivariate latent growth modeling. Int. J. Intercult. Rel. 2020, 74, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.; Hsu, F.; Lin, H. Workplace fun and work engagement in tourism and hospitality: The role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoun, P.S.; Mona, B. The association of psychological capital, career adaptability and career competency among hotel frontline employees. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Paek, S.Y.; Schuckert, M.; Kim, T.T.; Lee, G. Why is hospitality employees’ psychological capital important? The effects of psychological capital on work engagement and employee morale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Branigan, C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn. Emot. 2005, 19, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.; Sun, L.Y. A self-regulation model of zhong yong thinking and employee adaptive performance. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2018, 14, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F. The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slåtten, T.; Lien, G.; Horn, C.M.F.; Pedersen, E. The links between psychological capital, social capital, and work-related performance: A study of service sales representatives. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. 2019, 30, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckert, M.; Kim, T.T.; Paek, S.; Lee, G. Motivate to innovate: How authentic and transformational leaders influence employees’ psychological capital and service innovation behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. M. 2018, 30, 776–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Jensen, S.M. Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In Personnel Selection in Organizations; Schmitt, N., Broman, W.C., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Allworth, E.; Hesketh, B. Adaptive performance: Updating the criterion to cope with change. In Proceedings of the 2nd Australian Industrial and Organizational Psychology Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 1 January 1997. [Google Scholar]

- London, M.; Mone, E.M. Continuous learning. In The Changing Nature of Performance: Implications for Staffing, Motivation, and Development; Ilgen, D.R., Pulakos, E.D., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 119–153. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.R.; Jackson, S.E. Managing work role performance: Challenges for twenty-first century organizations and their employees. In The Changing Nature of Performance: Implications for Staffing, Motivation, and Development; Ilgen, D.R., Pulakos, E.D., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 325–365. [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh, B.; Neal, A. Technology and performance. In The Changing Nature of Performance: Implications for Staffing, Motivation, and Development; Ilgen, D.R., Pulakos, E.D., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 21–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Q.; Wang, Z. The construct of adaptive performance in management training settings. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 29, 614–617. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Lee, G.; Paek, S.; Lee, S. Social capital, knowledge sharing and organizational performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. M. 2013, 25, 683–704. [Google Scholar]

- Hanifan, L.J. The rural school community center. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1916, 67, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. The prosperous community. TAP 1993, 4, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Madjar, N. The contributions of different groups of individuals to employees’ creativity. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2005, 7, 182–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.S.; Chan, L.S. Social network, social trust and shared goals in organizational knowledge sharing. Inform. Manag. 2008, 45, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands—Resources model of burn out. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Long, X.; Li, X. Who will be more willing to operate social capital? Sociol. Rev. China 2018, 6, 44–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.A. Proactive personality and job performance: A social capital perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, A.; Nielsen, I.; Smyth, R.; Hirst, G. Mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between social support and wellbeing of refugees. Int. Migr. 2018, 56, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H. The relationships among intellectual capital, social capital, and performance: The moderating role of business ties and environmental uncertainty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H. Examining social capital, organizational learning and knowledge transfer in cultural and creative industries of practice. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, S.Y. Measurement in a cross-cultural environment: Survey translation issues. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2000, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J. Structural Equation Models, Concept and Understanding; Hannarae Publishers: Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Im, J. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS 22; Jibhyeonjae Press: Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L. Coefficient alpha and internal structure of test. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Avci, T. The effects of psychological capital and work engagement on nurses’ lateness attitude and turnover intentions. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.Y.; Huo, Y.Y.; Lan, J.B.; Chen, Z.G.; Lam, W. When do frontline hospitality employees take charge? Prosocial motivation, taking charge, and job performance: The moderating role of job autonomy. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2018, 60, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, S.A.; Tracey, J.B.; Fay, C.H.; Wright, P.M.; Snell, S.A.; Chang, S.; Gong, Y. Validation of a multidimensional HR flexibility measure. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1098–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Mitchell, T.R.; Liu, D. Event system theory: An event-oriented approach to the organizational sciences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).