Handrails through the Swamp? A Pilot to Test the Integration and Implementation Science Framework in Complex Real-World Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

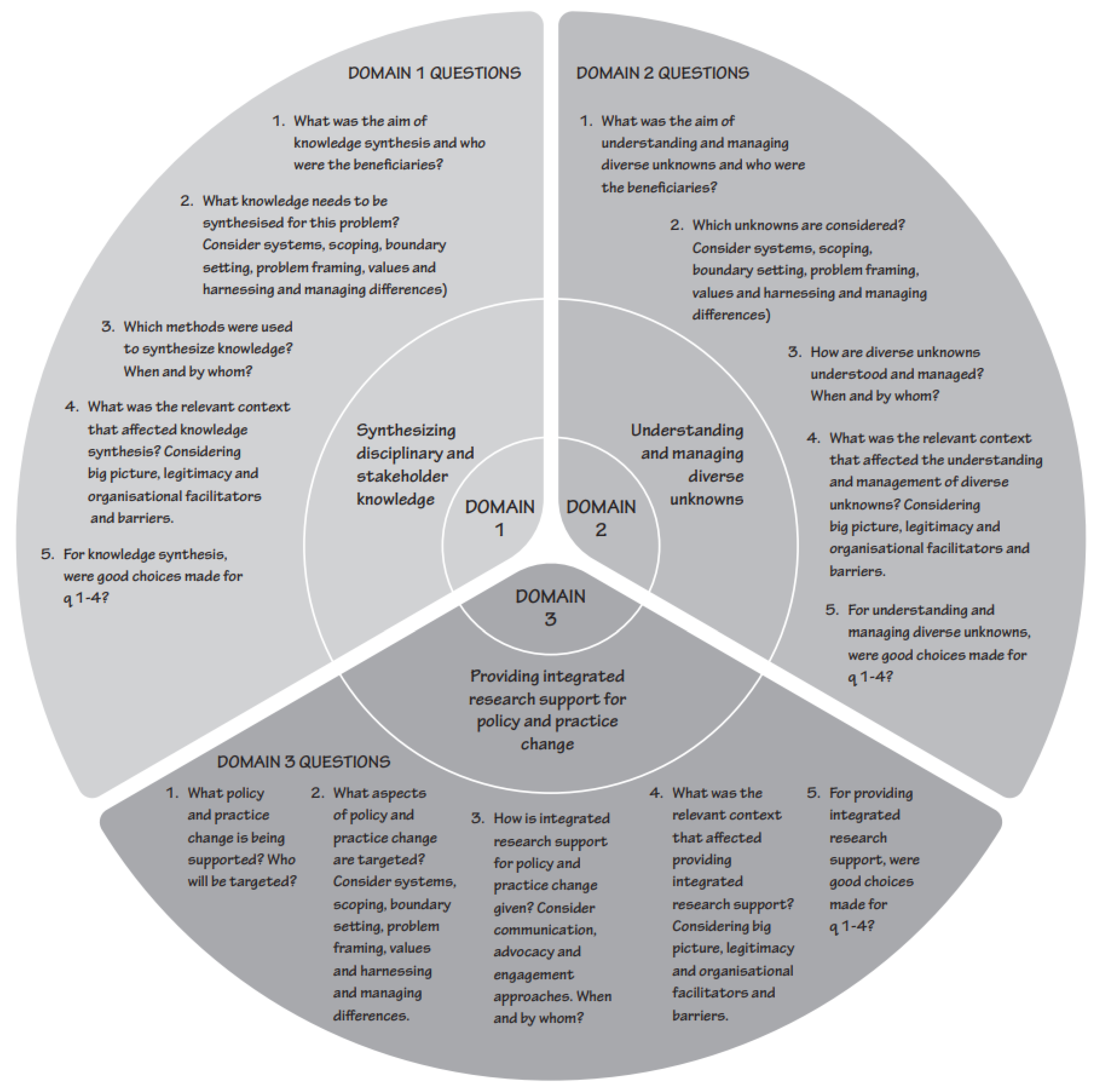

The Integration and Implementation Science Framework

2. Methods

2.1. Choosing Case Studies

2.2. Complexity Assessment

2.3. Deconstructing the i2S Framework

2.4. Case Study Data Collection

2.5. Scoring the Case Studies

2.6. Next-User Assessments

2.7. Study Limitations

3. Results Part 1: The Relationship between Consideration of the i2S Framework and Usefulness

4. Results Part 2: The Aspects of the Case Studies That Next Users Found Most Useful

4.1. Domain 1 Synthesising Disciplinary and Stakeholder Knowledge

4.1.1. Involving the Right Disciplines and the Right People

“we were trying to do science for policy and … the implementation was really key, so we wanted to have the people … most closely involved in implementation to be right in the heart of the research project making sure that it was credible and relevant and legitimate.”(CS2)

“These guys brought practical knowledge, combined with policy and research knowledge from the rest of the team.”(CS2)

“Needed to include various disciplines and end-users (farmers) to maintain integrity … and accelerate adoption.”(CS3)

4.1.2. Identifying the Problem and Synthesising Knowledge

“We used causal loop diagrams, CATWOE, innovation journey analysis, structures and functions framework, and multi- level perspective.” (Causal loop diagrams are used in System Dynamics to understand the behaviour of a system over time. CATWOE is a method to prompt thinking about a change in the system. Innovation journey analysis is a method for analysing the history of an innovation from inception to implementation. Structures and functions framework is a design framework for designing a change in a system, comprising three classes of variables: function, behaviour, and structure. Multi- level perspective is a framework describing the scaling up and out of innovations from niche, to regime, to landscape scale.)

4.1.3. Understanding Different Perspectives

“Each of the industries went away and did quite a significant canvassing and consultation and creation exercise with groups of farmers … to canvass perspectives within each of those groups. The project also included a pan sector reference group who were asked to look at things ‘from a broad industry focus’.”

4.2. Domain 2: Understanding and Managing Diverse Unknowns

4.3. Domain 3: Providing Integrated Research Support for Policy and Practice Change

4.3.1. Producing Relevant and Timely Outputs

4.3.2. Results Communicated Helpfully

“Compared to a group of people going off doing a piece of research and delivering a report or a product [at the end] and walking away, it couldn’t really have been further from that … having the next users on the team helps”.

4.3.3. Supporting Policy and Practice Change

“We tried to frame the research findings as a ‘service’ trying to make transparent the consequences and uncertainties to allow [next users] to make an informed decision. We also resisted the invitations to ‘tell us what the answer is’. The way we described [the results] was in the form of a coloured matrix with the likelihood of meeting the outcomes [desired] by the community. This meant that different scenarios could easily be compared.”

“were specifically identified as having skills, attributes and interest in translation and communication, [were] non-defensive in their approach and had empathy with target audience and were also comfortable with uncertainty”.

5. Discussion

5.1. Domain 1 Synthesising Disciplinary and Stakeholder Knowledge

5.2. Domain 2 Understanding and Managing Diverse Unknowns

5.3. Domain 3: Providing Integrated Research Support for Policy and Practice Change

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. i2S Framework Elements

| Domain | Question | Element |

| Synthesising disciplinary and stakeholder knowledge | What was the synthesis of disciplinary and stakeholder knowledge aiming to achieve and who is intended to benefit? | Purpose of combining disciplinary and Stakeholder (SH). Knowledge documented, Disciplinary and SH beneficiaries documented. |

| Which disciplinary and stakeholder knowledge was considered? | Systems tools used to help define the ‘problem’ and investigate links between problem elements. A recognised method used to develop a system view. Identification of different views on defining the problem. Identification of all the disciplines that could be relevant. Identification of all the stakeholders that could be relevant. A recognised methodology used for identification of relevant stakeholders and disciplines. Relevant science disciplines included and clarity on how decisions were made on what research was undertaken. Relevant stakeholders included and clarity on how decisions were made on which SH were considered relevant to include. All the relevant perspectives within each stakeholder group identified. Consideration given to how the problem was described or framed. Differences or conflicts managed. | |

| How was the disciplinary and stakeholder knowledge synthesised, by whom, and when? | Knowledge from the stakeholder and science participants synthesised using either formal or informal methods. Consideration given to who was the most appropriate person (s) to lead the integration and synthesis. Synthesising of knowledge (stakeholder with stakeholder, discipline with discipline, and stakeholder with discipline) occurs at multiple stages in project. | |

| What circumstances influenced the synthesis of disciplinary and stakeholder knowledge? | Overall context (and changes in context) influencing research project taken into account. Consideration given to the authorisation and legitimacy of the project. Project barriers and facilitators managed. | |

| Understanding and managing diverse unknowns | What was the understanding and management of diverse unknowns trying to achieve? | Clarity within research team, research stakeholders, and target audience on why managing for unknowns is important. |

| Which unknowns/uncertainties/risks considered? | Systematic consideration of unknowns (at outset and on-going through project life). Opportunities and risks associated with undertaking the project managed. | |

| How were the recognised unknowns and uncertainties managed or responded to? | Tools or processes used to help cope with uncertainty in research or implementation process, e.g., the precautionary principle, scenarios, sensitivity analysis, hedging, and adaptive management (acceptance approach). Identification and management of unknowns that were irreducible within the scope of the project. Surprises or the unexpected managed. Consideration of participants’ tacit knowledge (researchers, research stakeholders, and target audience) and management of any conflicts. Communication of uncertainty in research outputs and implications for policy or practice change. | |

| What circumstances influenced the management of unknowns | Management of project barriers to and facilitators of understanding, and managing unknowns within research and target audience organisations. | |

| III Providing integrated research support for policy and practice change | What is the integrated research support aiming to achieve, and who is intended to benefit? | Practice or policy change intent of the project clearly stated. Target audience (e.g., next-user, end-user) government, business, or civil society clearly stated. |

| Which aspects of policy and practice are targeted by the provision of integrated research support? | Consideration given to the target change as part of a system (e.g., if it was a change of regional council policy, was the way the regional council makes policy decisions considered, position in the policy cycle, reaction of lobby groups and community groups?) Identification of different systems views. Consideration given to how change happens-explicit or implicit (e.g., program logic, causal chain modelling, and theory of change). Identification of all the opportunities and target audiences relevant for the targeted change. Consideration of how research findings were framed or described for the target audience. Identified differences or conflicts in values between research team and target audience managed. | |

| How was integrated research support provided, by whom, and when? | Consideration of what methods were used to deliver research findings to the target audience. Consideration given to who was involved in the delivery of the research findings. Interaction with the target audience occurs at multiple stages in project. | |

| What circumstances might/did influence the provision of integrated research support for policy and practice change? | Overall context (and changes in context) influencing target change and target audience managed. Consideration given to the authorisation and legitimacy of the project to interact with target audience. Identification and management of difficulties in moving from doing the research (domain 1) in to trying to implement (domain 3). Project barriers and facilitators with target audience managed. |

Appendix B. Interview Questions

- Did the research include all the stakeholders and knowledge sources you thought necessary (in order for the results to be useful to you)? If not, who was excluded? And why is this important?

- What impact do you think that disciplinary and stakeholder selection had on research results?

- Do you think that mātauranga Māori was well enough integrated in the research outputs (in order for the results to be useful to you)? Why or why not? (Only for case study 1)

- Did the research provide a useful synthesis of all the relevant knowledge? If not, why not? Was something important excluded? If so, why?

- How did your involvement with the research improve your understanding of social, environmental, cultural, and economic interactions? (case study 1)/How did your involvement with the research improve your understanding of good management practice, and of land use, soil, and climate interactions? (case study 2)

- How did your involvement with the research improve your understanding of the diversity of stakeholder perspectives and values?

- Were your contributions well enough reflected in the research outputs?

- Do you think that the uncertainties in the research outputs were adequately described and managed?

- Were the uncertainties communicated helpfully for use in policy development?

- Did any groups attempt to exploit uncertainties or unknown factors in the research process? If yes, how were those attempts managed?

- Were any unknowns that you considered important not addressed or inadequately addressed? What were they and how do you think this impacted the research outputs?

- How well/adequately did the research process involve you in identifying unknowns?

- How well did the research process support your decision-making/policy development process?

- Did the research process produce relevant outputs and information for the decision-makers/policy-makers and did they (the outputs and information) come at the right time?

- Were the research outputs communicated helpfully for policy development?

- Were the research outputs helpful for integrating mātauranga Māori in the policy? (Only for case study 1).

- Do you think that the research outputs were presented impartially (as opposed to advocating for a position)?

- What is your overall evaluation of the research process and its outputs for the development and implementation of policy?

- How legitimate was the research process?

- How credible were the research results?

- How relevant were the research results to subsequent policy development?

- What would have led to a greater sense of legitimacy, credibility, and relevance regarding the research (if not covered above)?

Appendix C. Survey Questions

- Note: the questions below were generic to all projects surveyed. However, each project was sent a personalised questionnaire that referred to their particular project.

- My job/role/next-user/end-user group is: _____________________

- My level of familiarity with XXX research project is:

- 0 = not at all familiar

- 1 = slightly familiar

- 2 = somewhat familiar

- 3 = moderately familiar

- 4 = very familiar

- My frequency of engagement with the XXX research team was:

- 0 = never

- 1 = rarely

- 2 = occasionally/sometimes

- 3 = a moderate amount

- 4 = a great deal

- As a next or end-user of the XXX project please rate how useful the knowledge synthesis and research outputs were for understanding the problem and proposed solutions. Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, very useful = 4

- As a next or end-user of the XXX project, please rate how useful the knowledge synthesis and research outputs were for helping you understanding the perspectives and values of all the affected or interested parties. Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, and very useful = 4

- Was the project relevant to Māori? NA/Yes. If yes, how useful was the integration of mātauranga Māori into the research outputs for understanding the Māori perspective to the research problem and proposed solutions? Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, very useful = 4

- How usefully was the perspective of your industry sector (next-, end-user stakeholder group) reflected in the research knowledge synthesis and outputs? Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, very useful = 4

- Were any affected or interested parties and/or disciplinary knowledge sources not well represented or excluded from the research outputs? If yes, who and why should they have been better represented?

- How useful was the analysis of uncertainties and unknowns, which might influence the problem issue and proposed solutions, in the research outputs? Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, and very useful = 4

- How useful was the communication of uncertainties and unknowns, in the research outputs, for use in policy development or practice implementation? Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, very useful = 4

- Were any uncertainties or unknowns that you considered important not addressed or inadequately addressed in the research outputs? What were they and how do you think this impacted the usefulness of the research outputs?

- How useful were the research project outputs for supporting policy development or practice implementation? Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, and very useful = 4

- How useful were the research outputs in term of providing timely, relevant information for policy-makers or practitioners? Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, and very useful = 4

- How useful were the research outputs communicated for policy development or practice implementation? Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, and very useful = 4

- If mātauranga Māori was relevant to the project, how useful were the research outputs for integrating mātauranga Māori into policy development or practice change? Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, and very useful = 4, NA

- How objectively were the research results presented? Not at all objective = 0, moderately objective = 2, and very objective = 4

- What is your overall evaluation of the usefulness of the research project outputs for policy development or practice implementation? Not at all useful = 0, moderately useful = 2, and very useful = 4

- How legitimate was the research process and outputs? Not at all legitimate = 0, moderately legitimate = 2, and very legitimate = 4

- How credible were the research results and outputs? Not at all credible = 0, moderately credible = 2, and very credible = 4

- How relevant were the research results to subsequent policy development or practice implementation? Not at all relevant = 0, moderately relevant = 2, and very relevant = 4

- What would have led to a greater sense of legitimacy, credibility, and relevance of the research outputs?

References

- Roux, D.J.; Stirzaker, R.J.; Breen, C.M.; Lefroy, E.C.; Cresswell, H.P. Framework for participative reflection on the accomplishment of transdisciplinary research programs. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziulusoy, A.I.; Ryan, C.; McGrail, S.; Chandler, P.; Twomey, P. Identifying and addressing challenges faced by transdisciplinary research teams in climate change research. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, P.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; Osinski, A. Design features for social learning in transformative transdisciplinary research. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovers, S. Clarifying the imperative of integration research for sustainable environmental management. J. Res. Pract. 2005, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mauser, W.; Klepper, G.; Rice, M.; Schmalzbauer, B.S.; Hackmann, H.; Leemans, R.; Moore, H. Transdisciplinary global change research: The co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pohl, C.; Hadorn, G.H. Methodological challenges of transdisciplinary research. Nat. Sci. Soc. 2008, 16, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, C.; Cordell, D.; Fam, D. Beginning at the end: The outcome spaces framework to guide purposive transdisciplinary research. Futures 2015, 65, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Kerkhoff, L. Developing integrative research for sustainability science through a complexity principles-based approach. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D. Toward a science of transdisciplinary action research. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 38, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, L.J.; Hentati-Sundberg, J.; Giusti, M.; Goodness, J.; Hamann, M.; Masterson, V.A.; Meacham, M.; Merrie, A.; Ospina, D.; Schill, C.; et al. The undisciplinary journey: Early-career perspectives in sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bammer, G. Disciplining Interdisciplinarity: Integration and Implementation Sciences for Researching Complex Real-World Problems; ANU Press: Acton, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. Knowing-In-Action: The New Scholarship Requires a New Epistemology. Chang. Mag. High. Learn. 1995, 27, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, B.; Payne, T.; Munguia, O.M.D.O. Developing Reliable and Valid Measures for Science Team Process Success Factors in Transdisciplinary Research. Int. J. Interdiscip. Organ. Stud. 2015, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huutoniemi, K.; Klein, J.T.; Bruun, H.; Hukkinen, J. Analyzing interdisciplinarity: Typology and indicators. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frescoln, L.M.; Arbuckle, J.G. Changes in perceptions of transdisciplinary science over time. Futures 2015, 73, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, D.D.; Simpson, G.L.; McConnell, M.S.; Fair, J.M.; Baker, R.J. Transdisciplinary Research, Transformative Learning, and Transformative Science. Bioscience 2013, 63, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voinov, A.; Kolagani, N.; McCall, M.K.; Glynn, P.D.; Kragt, M.E.; Ostermann, F.O.; Pierce, S.A.; Ramu, P. Modelling with stakeholders—Next generation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 77, 196–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, M.; Nettle, R. Doing integration in catchment management research: Insights into a dynamic learning process. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 47, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berkett, N.; Fenemor, A.; Newton, M.; Sinner, J. Collaborative freshwater planning: Changing roles for science and scientists. Australas. J. Water Resour. 2018, 22, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carew, A.L.; Wickson, F. The TD Wheel: A heuristic to shape, support and evaluate transdisciplinary research. Futures 2010, 42, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polk, M. Achieving the promise of transdisciplinarity: A critical exploration of the relationship between transdisciplinary research and societal problem solving. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.J. How to be a more effective environmental scientist in management and policy contexts. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 64, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maasen, S.; Lieven, O. Transdisciplinarity: A new mode of governing science? Sci. Public Policy 2006, 33, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krueger, T.; Page, T.; Hubacek, K.; Smith, L.; Hiscock, K. The role of expert opinion in environmental modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 2012, 36, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tress, G.; Tress, B.; Fry, G. Analysis of the barriers to integration in landscape research projects. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, P.; Burton, R.J.F. Defining Terms for Integrated (Multi-Inter-Trans-Disciplinary) Sustainability Research. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1090–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, F.; Lyon, F. Transdisciplinary Environmental Research: A Review of Approaches to Knowledge Co-Production. 2014. Available online: http://researchprofiles.herts.ac.uk/portal/files/12138376/Harris_and_Lyon_Nexus_thinkpiece_002.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Duncan, R. Ways of knowing—Out-of-sync or incompatible? Framing water quality and farmers’ encounters with science in the regulation of non-point source pollution in the Canterbury region of New Zealand. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 55, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konig, B.; Diehl, K.; Tscherning, K.; Helming, K. A framework for structuring interdisciplinary research management. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, F.; Guillermin, M.; Dedeurwaerdere, T. A pragmatist approach to transdisciplinarity in sustainability research: From complex systems theory to reflexive science. Futures 2015, 65, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pennington, D. A conceptual model for knowledge integration in interdisciplinary teams: Orchestrating individual learning and group processes. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2016, 6, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D.; Fuqua, J.; Gress, J.; Harvey, R.; Phillips, K.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Unger, J.; Palmer, P.; Clark, M.A.; Colby, S.M.; et al. Evaluating transdisciplinary science. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2003, 5, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brandt, P.; Ernst, A.; Gralla, F.; Luederitz, C.; Lang, D.J.; Newig, J.; Reinert, F.; Abson, D.J.; von Wehrden, H. A review of transdisciplinary research in sustainability science. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 92, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.; Robson-Williams, M.; Nicholas, G.; Turner, J.A.; Smith, R.; Diprose, D. Transformation Is ‘Experienced, Not Delivered’: Insights from Grounding the Discourse in Practice to Inform Policy and Theory. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattor, K.; Betsill, M.; Huayhuaca, C.; Huber-Stearns, H.; Jedd, T.; Sternlieb, F.; Bixler, P.; Luizza, M.; Cheng, A.S. Transdisciplinary research on environmental governance: A view from the inside. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 42, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duncan, R.; Robson-Williams, M.; Fam, D. Assessing research impact potential: Using the transdisciplinary Outcome Spaces Framework with New Zealand’s National Science Challenges. Kōtuitui 2020, 15, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jahn, T.; Bergmann, M.; Keil, F. Transdisciplinarity: Between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, G.; Mancini, M.; Romano, E. Systems Engineering to Improve the Governance in Complex Project Environments. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 1395–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.T. Prospects for transdisciplinarity. Futures 2004, 36, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, T. Transdisciplinarity in the practice of research. In Transdisziplinäre Forschung: Integrative Forschungsprozesse Verstehen und Bewerten; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2008; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Apgar, J.M.; Argumedo, A.; Allen, W. Building Transdisciplinarity for Managing Complexity: Lessons from Indigenous Practice. Int. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Sci. Annu. Rev. 2009, 4, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, G. Systemic Intervention. In the Sage Handbook of Action Research, 3rd ed.; Bradbury-Huang, H., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley, G.; Ahuriri-Driscoll, A.; Foote, J.; Hepi, M.; Taimona, H.; Rogers-Koroheke, M.; Baker, V.; Gregor, J.; Gregory, W.; Lange, M.; et al. Practitioner identity in systemic intervention: Reflections on the promotion of environmental health through Māori community development. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2007, 24, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereijssen, J.; Srinivasan, M.; Dirks, S.; Fielke, S.; Jongmans, C.; Agnew, N.; Klerkx, L.; Pinxterhuis, I.; Moore, J.; Edwards, P. Addressing complex challenges using a co-innovation approach: Lessons from five case studies in the New Zealand primary sector. Outlook Agric. 2017, 46, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammer, G.; Smithson, M. Uncertainty and Risk: Multidisciplinary Perspectives; Earthscan: Routledge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robson-Williams, M.; Norton, N.; Davie, T.; Taylor, K.; Kirk, N. The Changing Role of Scientists in Supporting Collaborative Land and Water Policy in Canterbury, New Zealand. Case Stud. Environ. 2018, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, W. The Case for Case Studies in Confronting Environmental Issues. Case Stud. Environ. 2017, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Seawright, J.; Gerring, J. Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options. Polit. Res. Q. 2008, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareia, B. Qualitative and quantitative case study research method on social science: Accounting perspective. Int. J. Eng. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2016, 10, 3849–3854. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Small, B.; Robson-Williams, M.; Payne, P.; Turner, J.; Robson-Williams, R.; Horita, A. Co-innovation and Integration and Implementation Sciences: Measuring their research impact—An examination of five New Zealand primary sector case studies. NJAS 2021. (In press) [Google Scholar]

- Arkesteijn, M.; van Mierlo, B.; Leeuwis, C. The need for reflexive evaluation approaches in development cooperation. Evaluation 2015, 21, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complex Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use; The Guilford Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, M.C. Technical Report to Support Water Quality and Water Quantity Limit Setting Process in Selwyn Waihora Catchment: Predicting Consequences of Future Scenarios: Overview Report; Environment Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2014.

- Williams, R.H.; Brown, H.E.; Ford, R.; Lilburne, L.; Pinxterhuis, I.J.B.; Robson, M.C.; Snow, V.O.; Taylor, K.; von Pein, T. The Matrix of Good Management: Towards an understanding of farm systems, good management practice and nutrient losses in Canterbury. In Moving Farm Systems to Improved Nutrient Attenuation; Massey University: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2015; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.H.; Brown, H.E.; Ford, R.; Lilburne, L.; Pinxterhuis, I.J.B.; Robson, M.C.; Snow, V.O.; Taylor, K.; von Pein, T. The Matrix of Good Management: Defining good management practices and associated nutrient losses across primary industries. In Nutrient Management for the Farm, Catchment and Community; Massey University: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2014; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, M.C.; Brown, H.E.; Hume, E.; Lilburne, L.; McAuliffe, R.; Pinxterhuis, I.J.B.; Snow, V.O.; Williams, R.H.; B+LNZ; DEVELOPMENTMATTERS; et al. Overview Report—Canterbury Matrix of Good Management Project; Report no. R15/104; Environment Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2015.

- Pinxterhuis, I.; Dirks, S.; Bewsell, D.; Edwards, P.; Brazendale, R.; Turner, J.A. Co-innovation to improve profit and environmental performance of dairy farm systems in New Zealand. Rural Ext. Innov. Syst. J. 2018, 14, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, M.; Bewsell, D.; Jongmans, C.; Elley, G. Just-in-case to justified irrigation: Applying co-innovation principles to irrigation water management. Outlook Agric. 2017, 46, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M.S.; Bewsell, D.; Jongmans, C.; Elley, G. Research idea to science for impact: Tracing the significant moments in an innovation based irrigation study. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 212, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson-Williams, M.; Small, B.; Robson-Williams, R. Designing transdisciplinary projects for collaborative policymaking: The Integration and Implementation Sciences framework as a tool for reflection. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2020, 29, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funtowicz, S.; Ravetz, J. Science for post-normal age. Futures 1993, 25, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Jahn, J.; Knobloch, T.; Krohn, W.; Pohl, C.; Schramm, E. Methods for Trandisciplinary Research: A Primer for Practice; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, S.; Polk, M. Assessing the impact of transdisciplinary research: The usefulness of relevance, credibility, and legitimacy for understanding the link between process and impact. Res. Eval. 2018, 27, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Sigel, K. The role of public participation in managing uncertainty in the implementation of the Water Framework Directive. Eur. Environ. 2005, 15, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson-Williams, M.; Small, B.; Robson-Williams, R. A week in the life of a Transdisciplinary Research: Failures in research to support policy for water quality management in New Zealand’s South Island. In Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Failures Lessons Learned from Cautionary Tales; Fam, D., O’Rourke, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, C. From science to policy through transdisciplinary research. Environ. Sci. Policy 2008, 11, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, M.C.; Morehouse, B.J. The co-production of science and policy in integrated climate assessments. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, A. Make Your Science Sticky-Storytelling as a Science Communication Tool. Stockholm Environment Institute. Available online: https://www.sei.org/perspectives/make-science-sticky-storytelling-science-communication-tool/ (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- Torres, D.H.; Pruim, D.E. Scientific storytelling: A narrative strategy for scientific communicators. Commun. Teach. 2019, 33, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, D.W.; Clark, W.C.; Alcock, F.; Dickson, N.M.; Eckley, N.; Guston, D.H.; Jäger, J.; Mitchell, R.B. Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8086–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Midgley, G. Systemic Intervention: Philosophy, Methodology, and Practice; Kluwer/Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, A.; Brown, M.; Midgley, G. Systemic Intervention for Community OR: Developing Services with Young People (under 16) Living on the Streets; Kluwer/Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mierlo, B.; Arkesteijn, M.; Leeuwis, C. Enhancing the Reflexivity of System Innovation Projects with System Analyses. Am. J. Eval. 2010, 31, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klerkx, L.; Aarts, N.; Leeuwis, C. Adaptive management in agricultural innovation systems: The interactions between innovation networks and their environment. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, L.; Lemos, M.C. Creating usable science: Opportunities and constraints for climate knowledge use and their implications for science policy. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheruvelil, K.S.; Soranno, P.A.; Weathers, K.C.; Hanson, P.C.; Goring, S.J.; Filstrup, C.T.; Read, E.K. Creating and maintaining high-performing collaborative research teams: The importance of diversity and interpersonal skills. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Case Study Number | Case Study Name | Case Study Project Aim | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Selwyn Waihora | To support and inform a collaborative policy process in setting water quality and quantity limits in the Selwyn Waihora catchment. | [47,56] |

| 2 | Matrix of Good Management | To define primary industry-agreed good management practices and model the nutrient losses from farms operating using good management practice. | [57,58,59] |

| 3 | Nutrient Management | To develop and test on farm practices to help farmers to comply with changing and increasingly stringent regional water quality regulations. | [60] |

| 4 | Log Segregation | To develop cost-effective approaches to characterise and deal with variation in wood properties within and between trees to enhance value-added production. | [45] |

| 5 | Heifer Rearing | To improve the reproductive performance of New Zealand’s dairy herd by lifting the proportion of heifers entering the national herd at target live weight. | [60] |

| 6 | Water Use Efficiency | To improve on-farm irrigation decisions using better characterisation of irrigation demand and accurate short-term weather forecasts. | [61,62] |

| 7 | Primary Innovation | To gain greater economic benefit and a more sustainable future from the performance of New Zealand’s primary industries, including science through the use of Agricultural Innovation Systems. | https://www.beyondresults.co.nz/primary-innovation/about/ (accessed on 30 April 2021) |

| Case Study No. | Case Study | Method for Collecting Data from Next Users | Number of Next Users | Role of Next Users |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Selwyn Waihora | Interview | 5 | Decision-maker, planner, and policy-maker |

| 2 | Matrix of Good Management | Interview | 6 | Industry representative, planner, and policy-maker |

| 3 | Nutrient Management | Survey | 5 | Policy-maker, industry representatives, and farmers |

| 4 | Log Separation | Survey | 2 | Industry representatives |

| 5 | Heifer Rearing | Survey | 5 | Industry representatives, farmers |

| 6 | Water Use Efficiency | Survey | 4 | Policy-maker, industry representative, and farmers |

| 7 | Primary Innovation | Survey | 5 | Policy-makers, industry representatives, and researcher |

| Assessed Consideration of i2S Elements | Assessed Usefulness by Next Users | |

|---|---|---|

| Case study 1: Domain 1 | 3.30 | 3.2 |

| Case study 1: Domain 2 | 2.70 | 2.5 |

| Case study 1: Domain 3 | 3.34 | 3.2 |

| Case study 1: all frameworks | 3.1 | 3.0 |

| Case study 2: Domain 1 | 3.73 | 3.5 |

| Case study 2: Domain 2 | 2.63 | 2.8 |

| Case study 2: Domain 3 | 3.33 | 3.2 |

| Case study 2: all frameworks | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Case study 3: Domain 1 | 3.10 | 3.4 |

| Case study 3: Domain 2 | 2.90 | 3.5 |

| Case study 3: Domain 3 | 3.30 | 3.5 |

| Case study 3: all frameworks | 3.1 | 3.5 |

| Case study 4: Domain 1 | 2.68 | 3.0 |

| Case study 4: Domain 2 | 2.30 | 2.8 |

| Case study 4: Domain 3 | 2.65 | 3.0 |

| Case study 4: all frameworks | 2.5 | 2.9 |

| Case study 5: Domain 1 | 2.70 | 3.0 |

| Case study 5: Domain 2 | 1.67 | 1.8 |

| Case study 5: Domain 3 | 2.60 | 2.9 |

| Case study 5: all frameworks | 2.3 | 2.5 |

| Case study 6: Domain 1 | 3.04 | 3.3 |

| Case study 6: Domain 2 | 2.21 | 3.2 |

| Case study 6: Domain 3 | 3.35 | 3.2 |

| Case study 6: all frameworks | 2.9 | 3.2 |

| Case study 7: Domain 1 | 3.25 | 3.2 |

| Case study 7: Domain 2 | 3.19 | 3.4 |

| Case study 7: Domain 3 | 3.61 | 3.4 |

| Case study 7: all frameworks | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Variables | Correlations | |

|---|---|---|

| Consideration of i2S elements: all frameworks | Assessed usefulness by next users: all domains | 0.79 (p < 0.001) |

| Consideration of i2S elements: Domain 1 | Assessed usefulness by next users: Domain 1 | 0.84 (p = 0.018) |

| Consideration of i2S elements: Domain 2 | Assessed usefulness by next users: Domain 2 | 0.78 (p = 0.039) |

| Consideration of i2S elements: Domain 3 | Assessed usefulness by next users: Domain 3 | 0.81 (p = 0.027) |

| Variables | Correlations | |

|---|---|---|

| Consideration of i2S elements: all framework | Assessed usefulness by next users: overall assessment | 0.76 (p = 0.045) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Robson-Williams, M.; Small, B.; Robson-Williams, R.; Kirk, N. Handrails through the Swamp? A Pilot to Test the Integration and Implementation Science Framework in Complex Real-World Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105491

Robson-Williams M, Small B, Robson-Williams R, Kirk N. Handrails through the Swamp? A Pilot to Test the Integration and Implementation Science Framework in Complex Real-World Research. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105491

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobson-Williams, Melissa, Bruce Small, Roger Robson-Williams, and Nick Kirk. 2021. "Handrails through the Swamp? A Pilot to Test the Integration and Implementation Science Framework in Complex Real-World Research" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105491

APA StyleRobson-Williams, M., Small, B., Robson-Williams, R., & Kirk, N. (2021). Handrails through the Swamp? A Pilot to Test the Integration and Implementation Science Framework in Complex Real-World Research. Sustainability, 13(10), 5491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105491