Analysis of the Technological Evolution of Materials Requirements Included in Reactor Pressure Vessel Manufacturing Codes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Corrosion of materials and corrosion erosion, stress corrosion and corrosion-fatigue combined processes;

- Embrittlement by irradiation of the steels of the vessel.

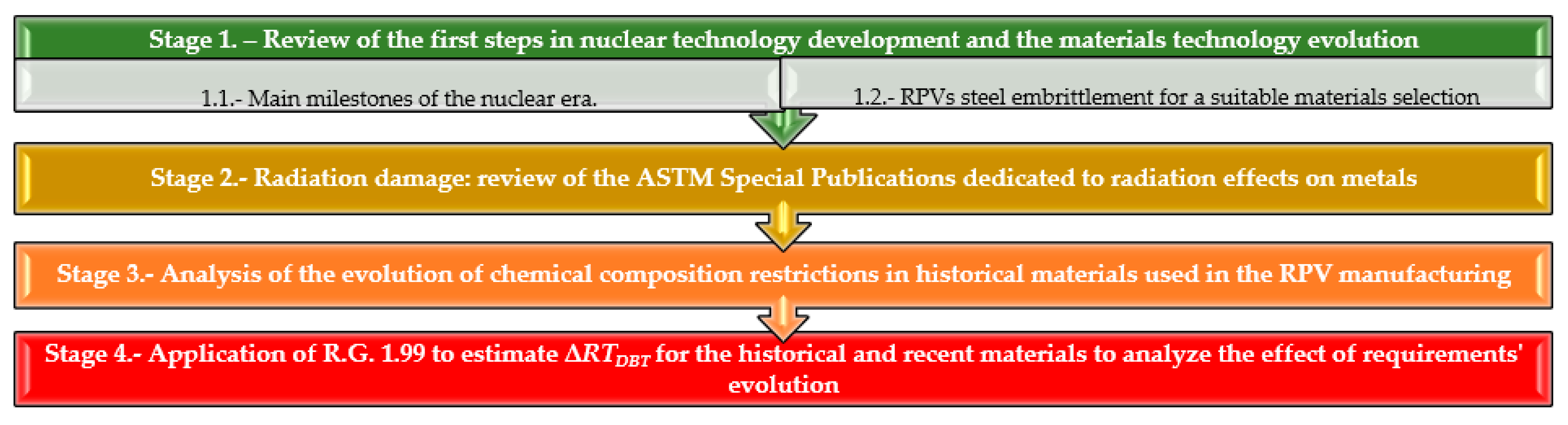

2. Methodology

- Stage 1. Review of the first steps in nuclear technology development and the materials technology evolution: main milestones of the nuclear era (Section 2.1.1) and review of contemporary data and theory regarding RPV steel embrittlement for a suitable materials selection (Section 2.1.2).

- Stage 2. Radiation damage: review of the ASTM Special Publications dedicated to radiation effects on metals.

- Stage 3. Analysis of the evolution of chemical composition restrictions in historical materials used in the RPV construction.

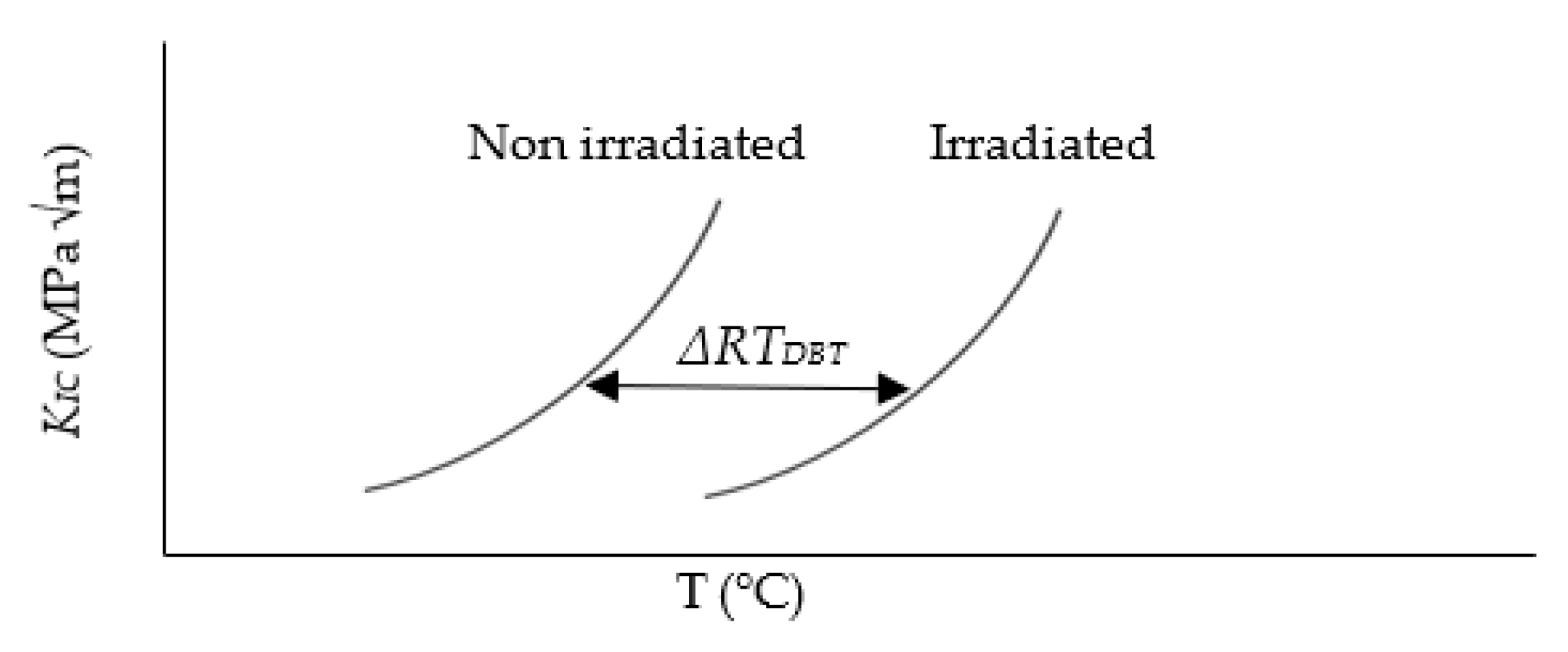

- Stage 4. Application of U.S. NRC R.G. 1.99 to estimate ductile-to-brittle transition temperature (ΔRTDBT) for both historical and contemporary materials to analyze the effect of the requirements’ evolution.

2.1. Stage 1.—Review of the First Steps in Nuclear Technology Development and Materials Technology Evolution

2.1.1. Main Milestones of the Nuclear Era

2.1.2. Review of the State of the Art of the RPVs Steel Embrittlement for Suitable Materials Selection

History of Irradiation Embrittlement Understanding. Identifying the Role of Different Parameters Since the Earliest Steps

Main Technological Characteristics Influencing Irradiation Embrittlement Characteristics

- Vanadium, V, increases the susceptibility of the material to neutron irradiation embrittlement [60] and decreases the weldability of the steel.

2.2. Stage 2.—Radiation Damage: Review of the ASTM SPECIAL Publications Dedicated to Radiation Effects on RPV Metals

3. Results

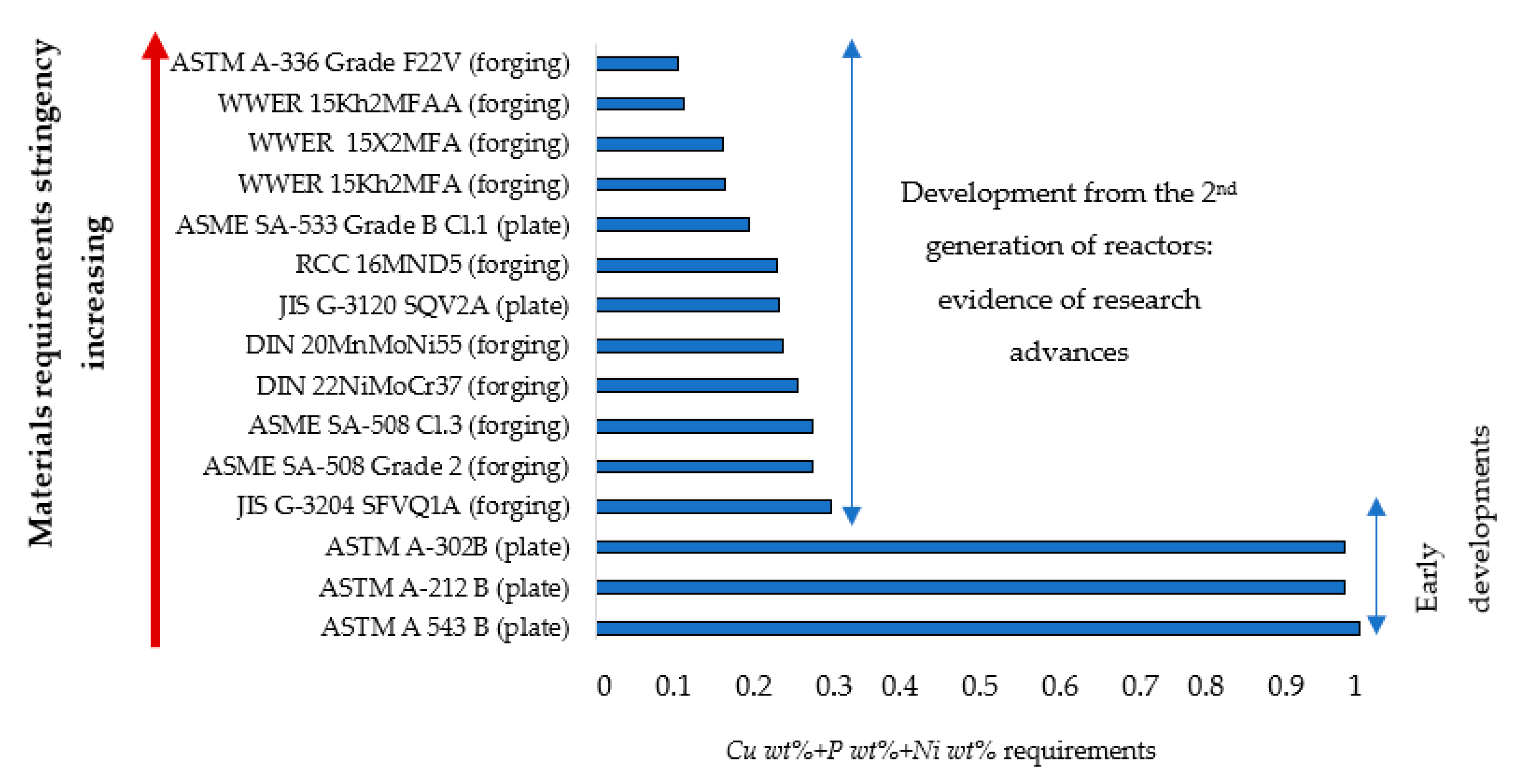

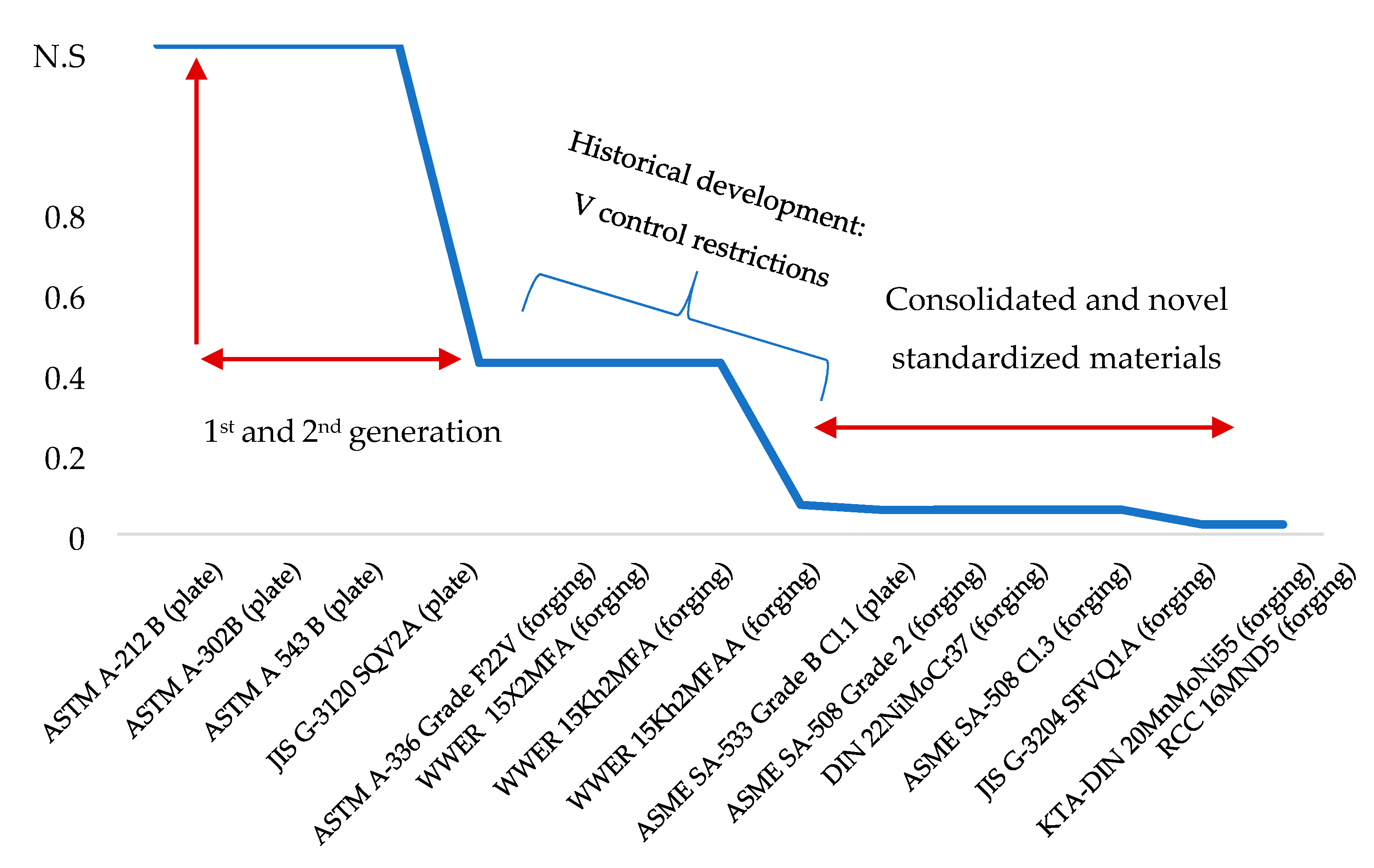

3.1. Stage 3.—Analysis of the Evolution of Chemical Composition Restrictions in Historical Materials Used in RPV Manufacturing

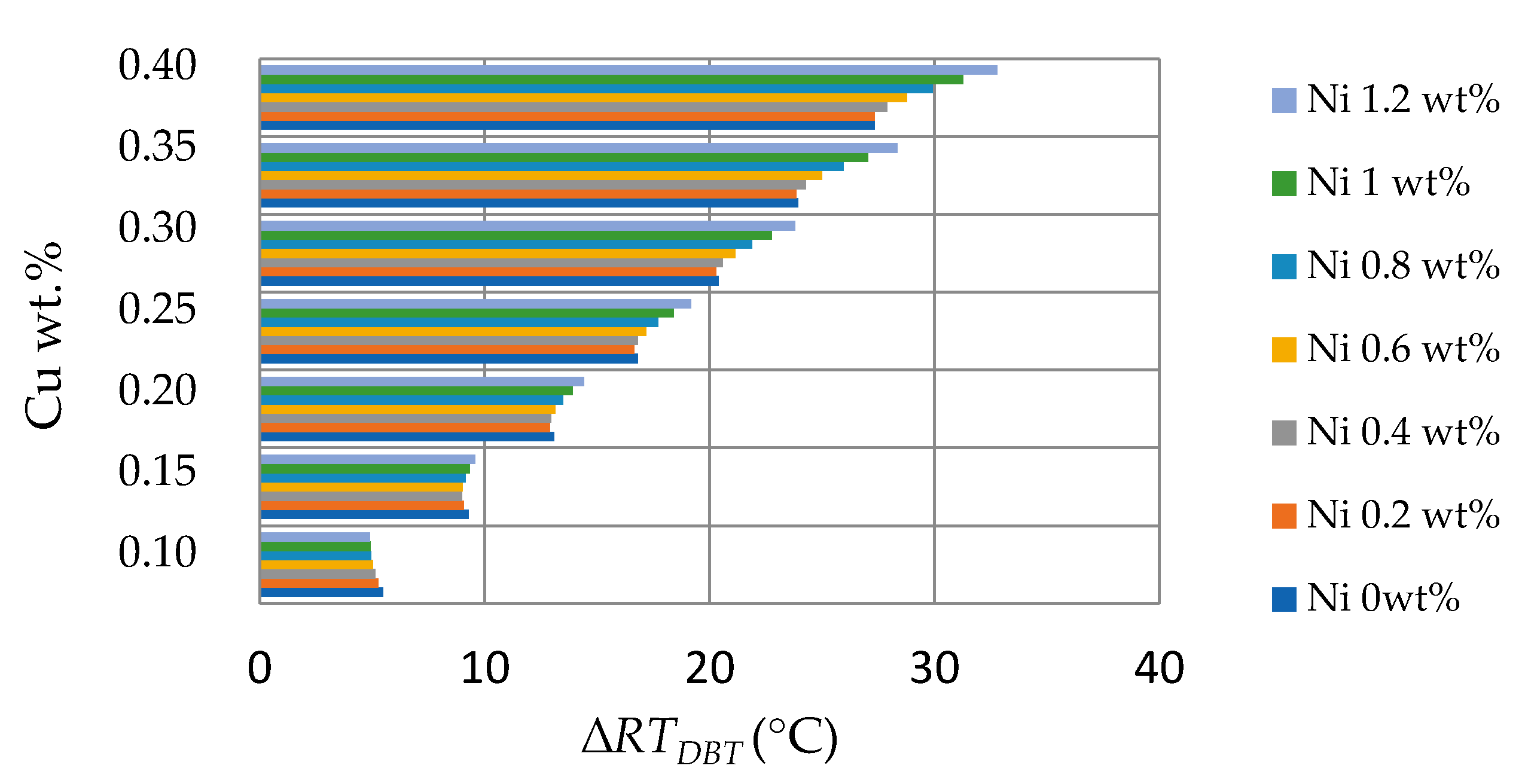

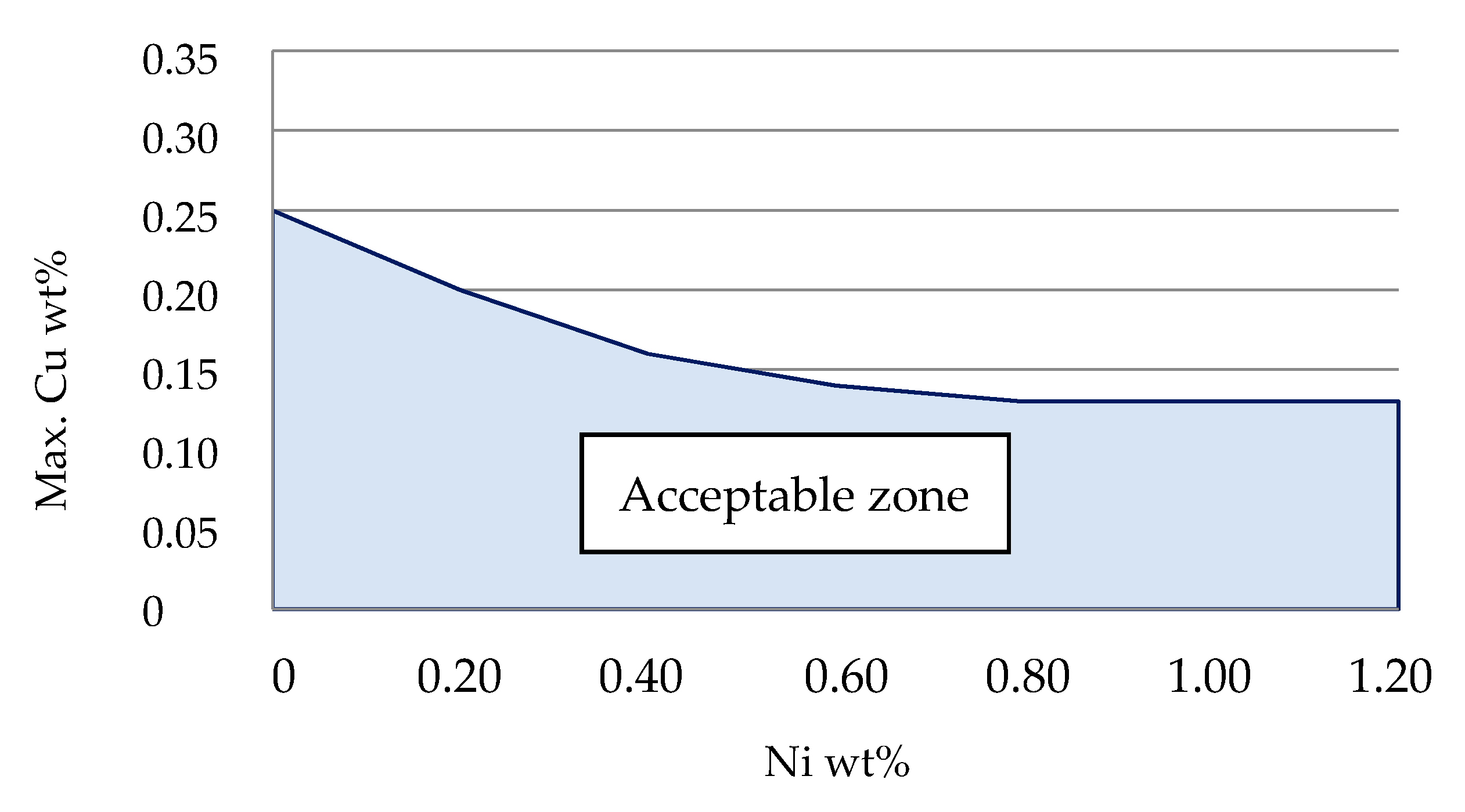

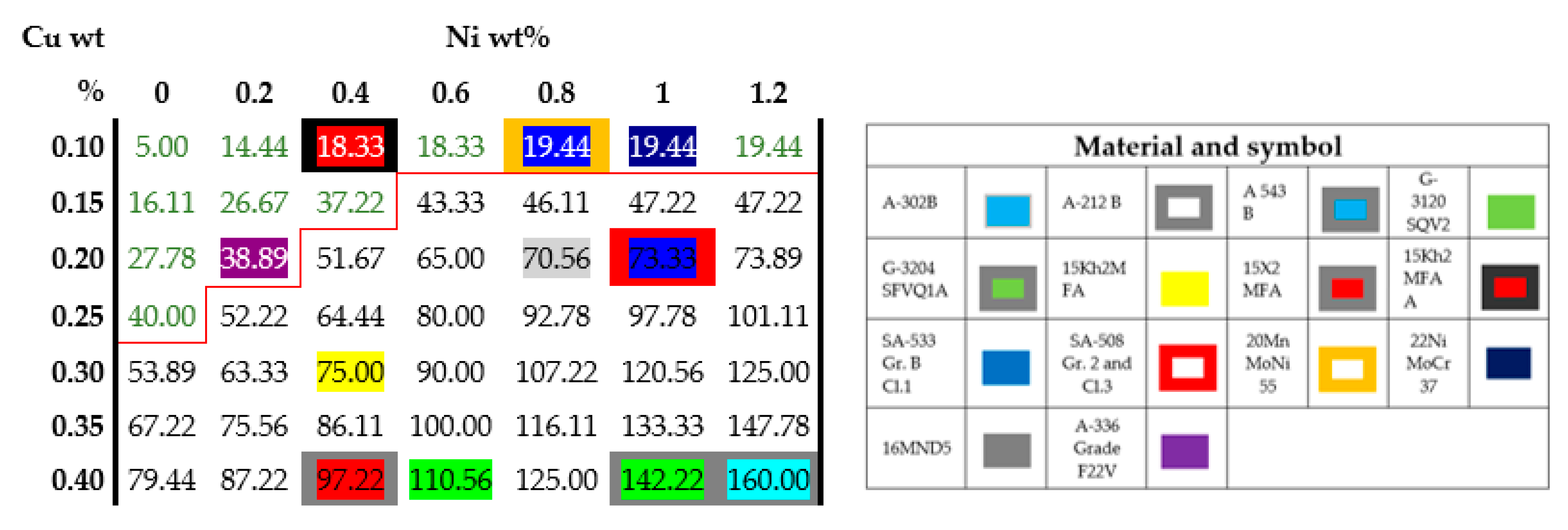

3.2. Stage 4.—Application of R.G. 1.99 to Estimate ΔRTDBT for the Historical and Recent Materials to Analyze the Effect of Requirements’ Evolution

4. Conclusions

- Steels with low levels of impurities are recommended for the current light water RPV steels and for the new-generation nuclear systems. However, it is recommended to review historical scientific advances related to the understanding of radiation embrittlement and the key factors involved in this phenomenon. This review allows one to analyze the evolution of the essential technological requirements and how they were integrated in the codes, standards and standardized specifications. Consequently, this is the rich technical heritage provided by the scientific research and the technical advancement that provides for safe and sustainable nuclear power generation now and in the future.

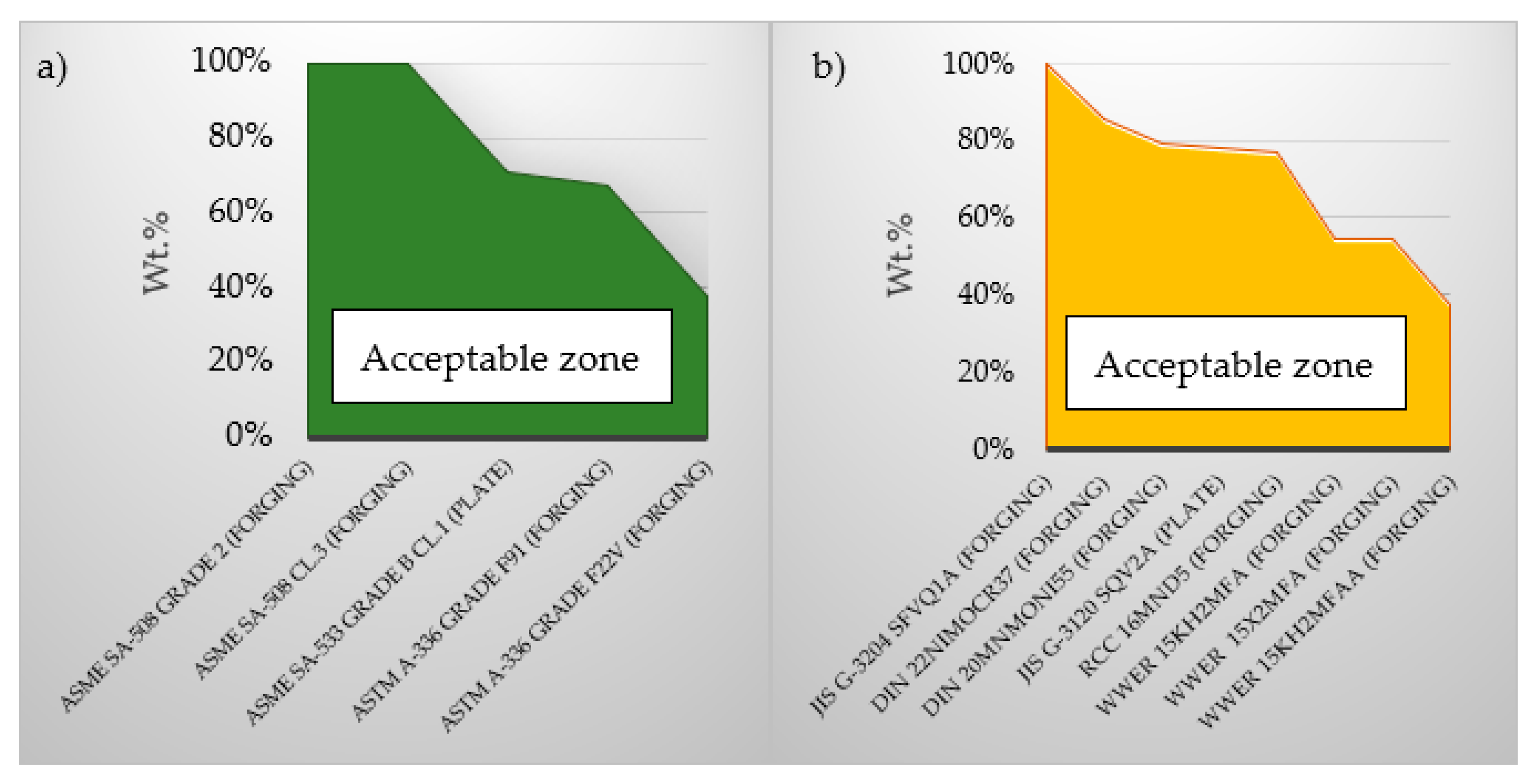

- According to NUREG and E-900-02 models, the ΔRTDBT is always lower than 40 °C (as established by KTA 3203 [55]) when the Cu wt.% is below 0.4% and the Ni wt.% is below 1.2%. This highlights that these theoretical models are less stringent than other experimental works that provide more stringent thresholds [51,52,53,54], according to information contained in Table 2. The nuclear industry is very conservative and, even nowadays, the model most consolidated and used is the U.S. NRC R.G. 1.99 Rev.2 because it is more stringent, meeting the requirements of several experimental works [51,52,53,54].

- The results obtained by applying the analysis based on the consolidated U.S: NRC R.G. 1.99 Rev.2 model allow for the definition of the best material options that correspond to some of the most widely used material specifications, such as WWER 15Kh2MFAA (used from the 1970s and 1980s; already in operation) ASME SA-533 Grade B Cl.1 (used in PWR 2nd–4th; already in operation), DIN 20MnMoNi55 and DIN 22NiMoCr37 (used in PWR 2nd–4th), as well as ASTM A-336 Grade F22V (current designs). This confirms a trend of improving the standards for improving nuclear safety.

- Finally, using a novel ductility–toughness ratio, the materials that exbibit the most balanced ductility–toughness ratio are: SA-508 Gr. 2, SA-533 Gr.B Cl.1, DIN 20NiMoCr37 and DIN 20MnMoNi55.

- Thus, in view of the results obtained, it can be concluded that the best options correspond to recently developed or well-established specifications used in the design of pressurized water reactors. These assessments endorse the fact that nuclear technology is in a state of continual development, with safety being its fundamental pillar.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raj, B.; Vijayalakshmi, M.; Rao, P.R.V.; Rao, K.B.S. Challenges in Materials Research for Sustainable Nuclear Energy. MRS Bull. 2008, 33, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Su, C.-C.; Nguyen, V.T. Nuclear Power Plant Location Selection in Vietnam under Fuzzy Environment Conditions. Symmetry 2018, 10, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serp, J.; Poinssot, C.; Bourg, S. Assessment of the Anticipated Environmental Footprint of Future Nuclear Energy Systems. Evidence of the Beneficial Effect of Extensive Recycling. Energies 2017, 10, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merk, B.; Litskevich, D.; Whittle, K.R.; Bankhead, M.; Taylor, R.J.; Mathers, D.; Mathers, D. On a Long Term Strategy for the Success of Nuclear Power. Energies 2017, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Arun, M. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Kim, M.-G.; Lee, J.I.; Lee, P.-S. Recent Advances in Ocean Nuclear Power Plants. Energies 2015, 8, 11470–11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.M.; Hong, S. Minimizing the Risks of Highway Transport of Hazardous Materials. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, L.; Forsberg, C.; Dolan, T.J. Electricity production. In Molten Salt Reactors and Thorium Energy; Woodhead Publishing: Duxford, UK, 2017; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, C.F. Power conversion system considerations for a high efficiency small modular nuclear gas turbine combined cycle power plant concept (NGTCC). Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 73, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ronco, A.; Giacobbo, F.; Lomonaco, G.; Lorenzi, S.; Wang, X.; Cammi, A. Preliminary Analysis and Design of the Energy Conversion System for the Molten Salt Fast Reactor. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Sebastián, M.A. Quantitative analysis of prediction models of hot cracking in stainless steels using standardized requirements. Sādhanā 2017, 42, 2147–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merayo, D.; Rodríguez-Prieto, Á.; Camacho, A.M. Analytical and numerical study for selecting polymeric matrix composites intended to nuclear applications. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L 2019, 233, 2072–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A. Análisis de Requisitos Tecnológicos de Materiales Especificados en Normativas Reguladas y su Repercusión Sobre la Fabricación de Recipientes Especiales Para la Industria Nuclear. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Sebastián, M.A. Materials selection criteria for nuclear power applications: A decision algorithm. JOM 2016, 68, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA TECDOC—1442. Guidelines for Prediction of Irradiation Embrittlement of Operating WWER—440 Reactor Pressure Vessels; International Atomic Energy Agency Publications: Vienna, Austria, 2005; pp. 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zinkle, S.J.; Busby, J.T. Structural materials for fission & fusion energy. Mater. Today 2009, 12, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Sebastián, M.A. Value analysis to optimize the manufacturing code selection process in the nuclear industry. In Proceedings of the 21th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Spain, 12–14 July 2017; AEIPRO-IPMA: Cadiz, Spain, 2017; pp. 721–729. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Sebastián, M.A. Evaluation method for pressure vessel manufacturing codes: The in-fluence of ASME unit conversion. Int. J. Mater. Prod. Technol. 2017, 54, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Merayo, D.; Sebastián, M.A. An educational software to reinforce the comprehensive learning of materials selection. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2018, 26, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odette, G.R. Recent progress in developing and qualifying nanostructured ferritic alloys for advanced fission and fusion ap-plications. JOM 2014, 66, 2427–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosemann, P.; Frazer, D.; Fratoni, M.; Bolind, A.; Ashby, M. Materials selection for nuclear applications: Challenges and opportunities. Scr. Mater. 2018, 143, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A. Evaluación cuantitativa del riesgo de fallos en servicio como herramienta para la gestión de la integridad de materiales en centrales nucleares. In Proceedings of the 45 Reunión Anual de la Sociedad Nuclear Española, Vigo, Spain, 23–28 September 2019; SNE: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Sebastián, M.A. Selection of candidate materials for reactor pressure vessels using irra-diation embrittlement prediction models and a stringency level methodology. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L 2019, 233, 965–976. [Google Scholar]

- DOE/NE-0088. The History of Nuclear Energy; Office of Nuclear Energy, Science and Technology: Washington DC, USA, 2006; p. 19.

- Fischer, D. History of the International Atomic Energy Agency: The First forty Years; International Atomic Energy Agency Publications: Vienna, Austria, 1997; p. 550. [Google Scholar]

- GOV/INF/2017/12-GC(61)/INF/8. International Status and Prospects of Nuclear Power 2017; International Atomic Energy Agency Publications: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NUREG/CR—5750. Rates of Initiating Events of US Nuclear Power Plants; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; p. 320.

- Murakami, K.; Sekimura, N.; Iwai, T.; Abe, H. Heterogeneity of ion irradiation-induced hardening in A533B reactor pressure vessel model alloys. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 53, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA NP-T-3.11. Integrity of Reactor Pressure Vessels in Nuclear Power Plants: Assessment of Irradiation Embrittlement Effects in Reactor Pressure Vessel Steels; International Atomic Energy Agency Publications: Vienna, Austria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, F. Radiation effects in solids. Phys. Today 1952, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trampus, P. Reactor Pressure Vessel Integrity in Light of the Evolution of Materials Science and Engineering. Mater. Sci. Forum 2005, 2005, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, F. On the Disordering of Solids by Action of Fast Massive Particles. In Crystal Growth, Discussions of the Faraday Society; Faraday Society: London, UK, 1949; pp. 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, F.; Koehler, J.S. The theory of lattice displacements produced during irradiation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy, Geneva, Switzerland, 8–20 August 1955; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesby, A.; Hancock, N.; Sansom, H. Effect of atomic-pile radiation on the elastic modulus of an austenitic steel. J. Nucl. Energy 1954, 1, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.C.; Berggren, R.G. Effect of neutron irradiation in steel. Proc. Am. Soc. Testing Mats. 1955, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, L.F. Radiation effects on steels. ASTM STP 1969, 276, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kangilaski, M. The Effects of Neutron Irradiation on Structural Materials; Battelle Memorial Institute Publications: Columbus, OH, USA, 1967; p. 253. [Google Scholar]

- Mager, T.R. Report on utilization of reactor pressure surveillance data in support of aging management. ASTM STP 1993, 1170, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pachur, D. Apparent Embrittlement Saturation and Radiation Mechanisms of Reactor Pressure Vessel Steels. ASTM STP 1981, 725, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, C.; Hyde, J. Radiation damage of reactor pressure vessels steels. In Comprenhensive Nuclear Materials; Konings, R.J., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 4, pp. 151–180. [Google Scholar]

- Soneda, N.; Dohi, K.; Nishida, K.; Nomoto, A.; Iwasaki, M.; Tsuno, S.; Akiyama, T.; Watanabe, S.; Ohta, T. Flux effect on neutron irradiation embrittlement of Reactor Pressure Vessel steels irradiated to high fluences. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Contribution of Materials Investigations to Improve the Safety and Performance of LWRs, Avignon, France, 26–30 September 2011; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- IAEA-TECDOC-1230. Reference Manual on the IAEA JRQ Correlation Monitor Steel for Irradiation Damage Studies; International Atomic Energy Agency Publications: Vienna, Austria, 2001; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, M.; Hernández, M. Programas de investigación sobre fragilización por irradiación de los aceros de vasija. An. Mecánica Electr. 2008, 5, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros, A.; Ahlstrand, R.; Bruynooghe, C.; Chernobaeva, A.; Kevorkyan, Y.; Erak, D.; Zurko, D. Irradiation temperature, flux and spectrum effects. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2011, 53, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, A.; Ahlstrand, R.; Bruynooghe, C.; von Estorff, U.; Debarberis, L. The role of pressure vessel embrittlement in the long term operation of nuclear power plants”, Section Engineering (II). In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting Spanish Nuclear Society, Cáceres, Spain, 17–19 October 2012; SNE: Cáceres, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Sebastián, M.A. Multicriteria materials selection for extreme operating conditions based on a multiobjective analysis of irradiation embrittlement and hot cracking prediction models. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2018, 14, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Klingensmith, D.; Odette, G.; Kikuchi, H.; Kamada, Y. Magnetic evaluation of irradiation hardening in A533B reactor pressure vessel steels: Magnetic hysteresis measurements and the model analysis. J. Nucl. Mater. 2012, 422, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odette, G.; Lucas, G.; Klingensmith, R. The Influence of Metallurgical Variables on the Temperature Dependence of Irradiation Hardening in Pressure Vessel Steels. In Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on effects of radiation on materials, Sun Valley, ID, USA, 20–23 June 1996; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1996; pp. 606–622. [Google Scholar]

- Odette, G.R.; Lucas, G.; Wirth, B.; Liu, C. Current understanding of the effects of environmental and irradiation variables on RPV embrittlement. In Proceedings of the 24th Water Reactor Safety Information Meeting, Bethesda, MD, USA, 21–23 October 1997; Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA; Volume 2, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nagay, Y.; Tang, Z.; Hassegawa, M.; Kanai, T.; Saneyasu, M. Irradiation—Induced Cu aggregations in Fe: An origin of em-brittlement of reactor pressure vessel steels. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 2001, 63, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Klingensmith, D. On the effect of dose rate on irradiation hardening of RPV steels. Philos. Mag. 2005, 85, 779–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrequin, P.; Soulat, P.; Houssin, B. Effect of residual elements and Nickel on the sensitivity to irradiation embrittlement of SA 508 CL.3 pressure vessel steel and weld. In Irradiation Embrittlement Thermal Annealing and Surveillance of Reactor Pressure Vessels; Steele, L.E., Ed.; International Atomic Energy Agency Publications: Vienna, Austria, 1979; Volume 79, pp. 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Stofanak, R.; Poskie, T.; Li, Y.; Wire, G. Irradiation damage behaviour of low alloy steel wrought and weld materials. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems—Water Reactors, San Diego, CA, USA, 1–5 August 1993; pp. 757–763. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaeva, A.; Nikolaev, Y.; Krjoikov, A. The contribution of grain boundary effects to low—Alloy steel irradiation embrittle-ment. J. Nucl. Mater. 1994, 218, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KTA 3203. Monitoring the Radiation Embrittlement of Material of the Reactor Pressure Vessel of Light Water Reactors; Nuclear Safety Standards Commission (KTA): Salzgitter, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Amayev, A.D.; Kryukov, A.M.; Sokolov, M.A. Radiation embrittlement of nuclear reactor pressure vessels steels: An interna-tional review. ASTM STP 1993, 1170, 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Sebastián, M.A.; Yanguas-Gil, A. Computer-aided sensitivity analysis of a multicriteria decision-making methodology for the evaluation of materials requirements stringency in nuclear components manufacturing. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. L. 2019, 233, 2094–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, W. The Fracture of Metals; Institution of Metallurgists: London, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, F.B.; Gladman, T. Metallurgical Developments in Carbon Steels; Iron and Steel Institute: London, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne, J.R. Significance of selected residual elements to the radiation sensitivity of steels. Nucl. Technol. 1982, 59, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Garmo, E.P.; Black, J.T.; Kohser, R.A. Materials and Processes in Manufacturing, 13th ed.; John Wyley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; p. 896. [Google Scholar]

- Odette, G.R.; Lucas, G.E. Recent progress in understanding reactor pressure vessel embrittlement. Radiat. Eff. Defect. S. 1998, 144, 189–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G.M.; Klepfer, H.H. Engineering Significance of Ferrite Grain Size on the Radiation Sensitivity of Pressure Vessel Steels. ASTM STP 1967, 426, 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund, K.; Zinkle, S.J.; Sand, A.E.; Granberg, F.; Averback, R.S.; Stoller, R.E.; Suzudo, T.; Malerba, L.; Banhart, F.; Weber, W.J.; et al. Primary radiation damage: A review of current understanding and models. J. Nucl. Mater. 2018, 512, 450–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleman, L.S. Survey of the Effects of Neutron Bombardment on Structural Materials. ASTM STP 1957, 208, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- KTA 3201.2. Components of the Reactor Coolant Pressure Boundary of Light Water Reactors—Part 2: Design and Analysis; Nuclear Safety Standards Commission (KTA): Salzgitter, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–162. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 208. Radiation Effects on Materials, American Society for Testing and Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1957; p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 341. Radiation Effects on Metals and Neutron Dosimetry; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Con-shohocken, PA, USA, 1963; p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 426. Effects of Radiation on Structural Metals; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1967; p. 706. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 484. Irradiation Effects on Structural Alloys for Nuclear Reactor Applications; American Society for Testing and Mate-rials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1970; p. 570. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 683. Effects of Radiation on Structural Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1979; p. 675. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 725. Effects of Radiation on Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1981; p. 759. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 819. Radiation Embrittlement and Surveillance of Nuclear Reactor Pressure Vessels: An International Study; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1983; p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 1175. Effects of Radiation on Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA USA, 1994; p. 1319. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 1325. Effects of Radiation on Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1999; p. 1120. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 1475. Effects of Radiation on Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2006; p. 406. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 909. Radiation Embrittlement of Nuclear Reactor Pressure Vessel Steels: An International Review; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1986; p. 297. [Google Scholar]

- R.G 1.99 Rev.2. Radiation Embrittlement of Reactor Vessel Materials; Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC): Washington, DC, USA, 1988; pp. 1–9.

- ASTM STP 1046. Effects of Radiation on Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1990; p. 672. [Google Scholar]

- NUREG/CR-6551. Improved Embrittlement Correlations for Reactor Pressure Vessel Steels; Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC): Washington, DC, USA, 1998; p. 134.

- ASTM E900. Standard Guide for Predicting Radiation-Induced Transition Temperature Shift in Reactor Vessel Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2002; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP-782. Effects of Radiation on Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1982; p. 1219. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP-1170. Radiation Embrittlement of Nuclear Reactor Pressure Vessel Steels: An International Review; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1993; p. 399. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP-1270. Effects of Radiation on Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1996; p. 1161. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 1447. Effects of Radiation on Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004; p. 758. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 1492. Effects of Radiation on Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM STP 1572. Effects of Radiation on Nuclear Materials; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A. Fragilización por irradiación neutrónica de la vasija: Algunas consideraciones para la selección de mate-riales. In Proceedings of the 42 Reunión Anual de la Sociedad Nuclear Española, Santander, Spain, 28–30 September 2016; SNE: Madrid, Spain; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Dailey, R.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Humrickhouse, P.; Corradini, M.L. Accident tolerant fuels (FeCrAl Cladding & Coating) performance analysis in Boiling Water Reactor (BWR) by the MELCOR 1.8.6 UDGC. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2021, 371, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yeom, H.; Humrickhouse, P.; Sridharan, K.; Corradini, M. Effectiveness of Cr-Coated Zr-Alloy Clad in Delaying Fuel Degradation for a PWR During a Station Blackout Event. Nucl. Technol. 2020, 206, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Sebastián, M.A. New decision methodology for selecting manufacturing codes of nuclear reactor pressure-vessels. In Proceedings of the Annals of DAAAM for 2015 and Proceedings of the 26th DAAAM International Symposium, Zadar, Croatia, 18–25 October 2015; DAAAM International: Vienna, Austria; pp. 693–698. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Camacho, A.M.; Sebastián, M.A. Consideraciones técnicas acerca de los programas regulados para la vigilancia de las propiedades de aceros de vasija en reactores nucleares. Ind. Química 2016, 33, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

| Chronology | Description | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1939 January | Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman report in the journal Naturwissenschaften that they have bombarded and split the uranium atom into two or more lighter elements. | • |

| 1942 December | The first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction occurs at the University of Chicago. | • |

| 1946 August | The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 creates the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to control nuclear energy development and explore peaceful uses of nuclear energy. | ◦ |

| 1951 December | In Arco, Idaho, Experimental Breeder Reactor I produces electric power, lighting four light bulbs. | • |

| 1953 March | Nautilus starts its nuclear power units for the first time. | • |

| 1953 December | President Eisenhower delivers his “Atoms for Peace” speech before the United Nations. | ◦ |

| 1954 August | President Eisenhower signs The Atomic Energy Act of 1954, the first major amendment of the original Act. | ◦ |

| 1955 January | The AEC announces the Power Demonstration Reactor Program. | ◦ |

| 1955 July | Arco, Idaho, population 1000, becomes the first town powered by a nuclear powerplant. | • |

| 1955 August | Geneva (Switzerland) hosts the first United Nations International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. | ◦ |

| 1957 July | The first power from a civilian nuclear unit is generated by the Sodium Reactor Experiment at Santa Susana, California. | • |

| 1957 October | The United Nations creates the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna, Austria, to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy. | ◦ |

| 1957 December | The world’s first large-scale nuclear powerplant begins operation in Shippingport, Pennsylvania. The plant reaches full power three weeks later and supplies electricity to the Pittsburgh area. | • ◦ |

| Early 1960s | Small nuclear power generators are first used in remote areas to power weather stations and to light buoys for sea navigation. | • |

| 1961 November | The U.S. Navy commissions the world’s largest ship, the U.S.S. Enterprise (nuclear-powered aircraft carrier with the ability to operate for up to 740,800 km without refueling). | • |

| 1965 April | The first nuclear reactor in space (SNAP-10A) is launched by the United States. | • |

| 1970 March | The United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union and 45 other nations ratify the Treaty for Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. | ◦ |

| 1974 October | The Energy Reorganization Act of 1974 divides AEC functions in two new agencies: Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA), to carry out research; and Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), to regulate nuclear power. | ◦ |

| 1977 October | Department of Energy (DOE) begins operations. | ◦ |

| 1979 March | The worst accident in U.S. commercial reactor history occurs at the Three Mile Island nuclear power station near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The accident was caused by a loss of coolant from the reactor core due to a combination of mechanical malfunction and human error. | ◊ |

| 1980 March | DOE initiates the Three Mile Island accident research and development program to develop technology for disassembling and de-fueling the damaged reactor. The program continued for 10 years and made significant advances in developing new nuclear safety technology. | ◊ |

| 1986 April | Operator error causes two explosions at the Chernobyl No. 4 nuclear powerplant in the former Soviet Union. The reactor has an inadequate containment building, and large amounts of radiation escape. A plant of such design would not be licensed in the United States or Western Europe. | ◊ |

| 1989 April | The NRC proposes a plan for reactor design certification, early site permits, and combined construction and operating licenses. | • ◦ ◊ |

| 1990 March | DOE launches a joint initiative to improve operational safety practices at civilian nuclear powerplants in the former Soviet Union. | ◦ ◊ |

| 2000 December | The last of the reactors at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant are shut down. | ◊ |

| Early 2004 | The first of the late third-generation units was ordered for Finland–a 1600 MWe European PWR (EPR). | • |

| 2011 March | Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident occurs after a severe earthquake off the coast of Japan. This caused the establishment of more stringent safety specifications for reactors around the world. | ◊ |

| 2020 July | ITER begins its assembly with the support of 35 countries. | • |

| Chemical Element | Established Scientific Threshold (Maximum wt.%) |

|---|---|

| Cu | 0.10 |

| P | 0.02 |

| Ni | 1.00 |

| Year | Ref. ASTM | Structural Materials | Testing Conditions | Highlighted Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ϕ (n/cm2) | T (°C) | ||||

| 1957 | STP-208 [67] | ASTM A-212B | 1.0·1019 1.0·1020 | 60 93 | Δ (UTSI − UTSN-I) = 30.5%, Δ (YpI − YpN-I) = 7.7% Δ (UTSI − UTSN-I) = 87.2%, Δ (YpI − YpN-I) = 29.5% |

| ASTM A-302B | 3.7·1018 | 240–280 | Δ (UTSI − UTSN-I) = 10.9%, Δ (YpI − YpN-I) = 4.2% | ||

| 1962 | STP-341 [68] | ASTM A-212B | 2·1018 | 25 | No appreciable changes in the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature. |

| 1967 | STP-426 [69] | ASTM A-212B/302B | 2·1018 | 300 | ΔRTDBT = 18.33 °C. |

| 1970 | STP-484 [70] | ASTM A-212B | 9.4·1018 | 260 | ΔRTDBT = 35 °C |

| A302B | 8.0·1018 2.0·1020 | Δ (UTSI − UTSN-I) = 7.61%, Δ (YpI − YpN-I) = 39.74% Δ (UTSI − UTSN-I) = 31.42%, Δ (YpI − YpN-I) = 73.08% | |||

| A542 | 6.0·1018 3.0·1020 | Δ (UTSI − UTSN-I) = 10.24%, Δ (YpI − YpN-I) = 27.52% Δ (UTSI − UTSN-I) = 43.31%, Δ (YpI − YpN-I) = 66.97% | |||

| 1979 | STP-683 [71] | A302B | 3.0·1019 | 288 | ΔRTDBT = 55 °C |

| A533B | 5–7·1019 | ΔRTDBT = 12 − 35 °C | |||

| 1981 | STP-725 [72] | A533B | 1018–1020 | Embrittlement is maximized at 150 °C. | |

| 1983 | STP-819 [73] | A533B | 1.2·1019 | 290 | ΔRTDBT = 24 °C |

| A508-3 | 1.9·1019 | 290 | ΔRTDBT = 27 °C | ||

| 1994 | STP-1175 [74] | A533-B | 0.7·1018 | 280 | ΔRTDBT = 7–12 °C. |

| 1999 | STP 1325 [75] | A533-B | 4.0·1023 | 290 350 | Δ (YpI − YpN-I) = 100 MPa for Cu between 0.5 and 0.9 wt.%. Δ (YpI − YpN-I) = 180 MPa for Cu between 0.5 and 0.9 wt.%. |

| 2006 | STP 1475 [76] | A508-2/ A533-B | 1019 | 282 | A 508-2: ΔRTDBT = 11% greater after 209 000 h (24 years) at about 282 °C. A533-B: ΔRTDBT = 8% greater after 209 000 h (24 years) at about 282 °C. |

| ASTM Report or Published Standard | Highlighted Contributions | |

|---|---|---|

| STP-909 (1986) [77] | Odette presented the equation: | |

| ∆RTDBT (°C) = 200·Cu·(1 + 1.38(erf (0.3·Ni-Cu)/Cu) + 1) × (1 − e(−φ/0.11))1.36 φ18 | (1) | |

| R.G. 1.99 Rev.2 (1988) [78] | ΔRTDBT = (CF) × f (0.28 – 0.10 log f) | (2) |

| where CF is the chemical factor provided by R.G. 1.99 Rev. 2, which is a function of Cu and Ni content in wt.%; and f is the neutron flux in n/cm2. | ||

| STP-1046 (1990) [79] | Miannay presented the equation: | |

| ∆RTDBT (°C) = 10.98 + 316.4·(P- 0.008) + 225.29·(Cu – 0.08) + 12.10·(Ni – 0.7) + 248.31 × (Cu – 0.08) ·(Ni – 0.7)) ·φ0.70 | (3) | |

| NUREG CR-6551 (1998) [80] | ΔRTDBT = SMD + CRP | (4) |

| SMD = A exp [CTc/(Tc + 460)] [1 + CP P] (φt)α | (5) | |

| CRP = B [1 + CNi Νiη] F(Cu) G(φt) | (6) | |

| To obtain the CRP contribution, it is necessary to calculate the F(Cu) (Equation (6)) and the G(φt) (Equation (7)) parameters. | ||

| (7) | ||

| G(φt) = ½ + ½ tanh {[log (φt + Ct tf) − μ]/σ} | (8) | |

| ASTM E900-02 [81] | ΔRTDBT = SMD + CRP + Bias | (9) |

| The Bias term was introduced, | ||

| Bias | (10) | |

| where ti is the irradiation time |

| ASTM Report or Published Standard | Highlighted Findings |

|---|---|

| STP-782 (1982) [82] | The sensitivity to irradiation embrittlement depends on Cu wt.% contents from 0.03 to 0.10 wt.%, as well as on Ni contents for A508-2 and A508-3 and testing 1018–1020 n/cm2. |

| STP-1170 (1993) [83] | Amayev proposed that P ≥ 0.02 wt.% negatively affects the mechanical properties of the material. Mager [38] did not find dependence between neutron flux rates from ϕ = 2.5 × 1018 n/cm2 to ϕ = 8.8 × 1019 n/cm2. |

| STP-1270 (1996) [84] | Odette presented a Cu limitation: 0.10 wt.%. |

| STP 1447 (2004) [85] | The NRC draft correlation adds a term representing an additional shift if the steel has been exposed to more than 97,000 h of high temperature. |

| STP 1492 (2008) [86] | The A533B steel plate with high content of P exhibited significant hardening, as well as grain boundary P segregation, and a large ΔRTDBT of 230 °C due to neutron irradiation to a fluence of 6.9·1019 n/cm2 and E ≤ 1 MeV at 290 °C. |

| STP 1572 (2014) [87] | Adequate safety margins of ΔRTDBT with respect to the German KTA 3201.2. standard [66] curve were observed for all materials with Cu ≤ 0.15% and Ni ≤ 1.1% for which the ΔRTDBT curve is valid. |

| Material | Chronology | Type and Generation of Reactor | Design Code | Cu | Ni | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASTM A-302B (plate) | 1960s | PWR 1st | ASME B&PVC | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

| ASTM A-212 B (plate) | 1960s (withdrawn 1967) | PWR 1st | ‒ | ‒ | X | |

| ASTM A 543 B (plate) | 1960s | PWR 1st | ‒ | X | X | |

| JIS G-3120 SQV2A (plate) | 1970s–1980s | PWR 2nd | JSME | ‒ | X | X |

| JIS G-3204 SFVQ1A (forging) | 1980s | PWR 2nd–3rd | ‒ | X | X | |

| WWER 15Kh2MFA (forging) | 1970s–1980s | WWER-440 | Gosgortechnadzor | ‒ | X | X |

| WWER 15 × 2MFA (forging) | 1970s–1980s | WWER-440 | X | X | X | |

| WWER 15Kh2MFAA (forging) | 1970s–1980s | WWER-440 | X | X | X | |

| ASME SA-533 Gr. B Cl.1 (plate) | 1980s | PWR 2nd–3rd | ASME B&PVC | X | X | X |

| ASME SA-508 Grade 2 (forging) | 1980s | PWR 2nd–3rd | X | X | X | |

| ASME SA-508 Cl.3 (forging) | 1980s–present | PWR 2nd–4th; PHWR | X | X | X | |

| DIN 20MnMoNi55 (forging) | 1980s–present | PWR 2nd–4th; PBMR | KTA | X | X | X |

| DIN 22NiMoCr37 (forging) | 1980s–present | PWR 2nd–4th | X | X | X | |

| RCC 16MND5 (forging) | 1980s–present | PWR 2nd–4th | RCC-MR | X | X | X |

| ASTM A-336 Grade F22V (forging) | (present) | GT-MHR (General Atomics) | ASME B&PVC | X | X | X |

| RPV Material | Chemical Requirements (Maximum wt.%) | Mechanical Requirements | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | P | Ni | Si | V | Maximum Elongation (EL) in % | Maximum σy/UTS | |

| ASTM A 212B, | N.S. | 0.035 | N.S. | 0.30 | N.S. | 23 | 0.68 |

| ASTM A 302B | N.S. | N.S. | N.S. | 0.40 | N.S. | 15 | 0.56 |

| ASTM A 543 B | N.S. | 0.020 | 4.00 | 0.40 | N.S. | 18 | 0.56 |

| ASME SA 533 Grade B Cl.1 | 0.12 | 0.015 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 18 | 0.56 |

| JIS G 3204 SFVQ1A | N.S. | 0.035 | 0.70 | 0.30 | N.S. | 18 | 0.54 |

| ASME SA 508 Grade 2 | 0.20 | 0.025 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 16 | 0.64 |

| DIN 22NiMoCr37 | 0.11 | 0.025 | 1.00 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 16 | 0.64 |

| ASME SA 508 Grade 3; | 0.20 | 0.025 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 16 | 0.64 |

| DIN 20MnMoNi55 | 0.12 | 0.012 | 0.85 | 0.35 | 0.02 | 19 | 0.59 |

| RCC 16 MND5 | 0.20 | 0.020 | 0–80 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 20 | 0.66 |

| JIS G 3204 SFVQ1A | N.S. | 0.025 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 18 | 0.72 |

| ASTM A 336 Grade F22V | 0.20 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.35 | 20 | 0.60 |

| WWER 15X2MF | 0.30 | 0.020 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 14 | 0.80 |

| WWER 15Kh2MFA | N.S. | 0.025 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 14 | 0.80 |

| WWER 15Kh2MFAA | 0.08 | 0.012 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 15 | 0.81 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Prieto, A.; Frigione, M.; Kickhofel, J.; Camacho, A.M. Analysis of the Technological Evolution of Materials Requirements Included in Reactor Pressure Vessel Manufacturing Codes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105498

Rodríguez-Prieto A, Frigione M, Kickhofel J, Camacho AM. Analysis of the Technological Evolution of Materials Requirements Included in Reactor Pressure Vessel Manufacturing Codes. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105498

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Prieto, Alvaro, Mariaenrica Frigione, John Kickhofel, and Ana M. Camacho. 2021. "Analysis of the Technological Evolution of Materials Requirements Included in Reactor Pressure Vessel Manufacturing Codes" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105498

APA StyleRodríguez-Prieto, A., Frigione, M., Kickhofel, J., & Camacho, A. M. (2021). Analysis of the Technological Evolution of Materials Requirements Included in Reactor Pressure Vessel Manufacturing Codes. Sustainability, 13(10), 5498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105498