Strengthening the Call for Intentional Intergenerational Programmes towards Sustainable Futures for Children and Families

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Grounding Theories for Conceptual Development

2.1. Conceptual Process

2.2. Cultural–Historical Perspectives

2.3. Cultural Artefacts

- (1)

- Primary artefacts: traditionally a hammer, a needle, scissors or a camera; used in production and labour.

- (2)

- Secondary artefacts: relating to primary artefacts (such as a user manual for a camera or instructions for cooking (a recipe).

- (3)

- Tertiary artefacts: representations of secondary artefacts, symbols, theories and models (imagining new ideas).

2.4. Cultural–Historical Wholeness Approach—Visual Model

2.5. Childhood Studies and Glocal Understandings

2.6. Characterisations of Intergenerational Programmes in the Field of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC)

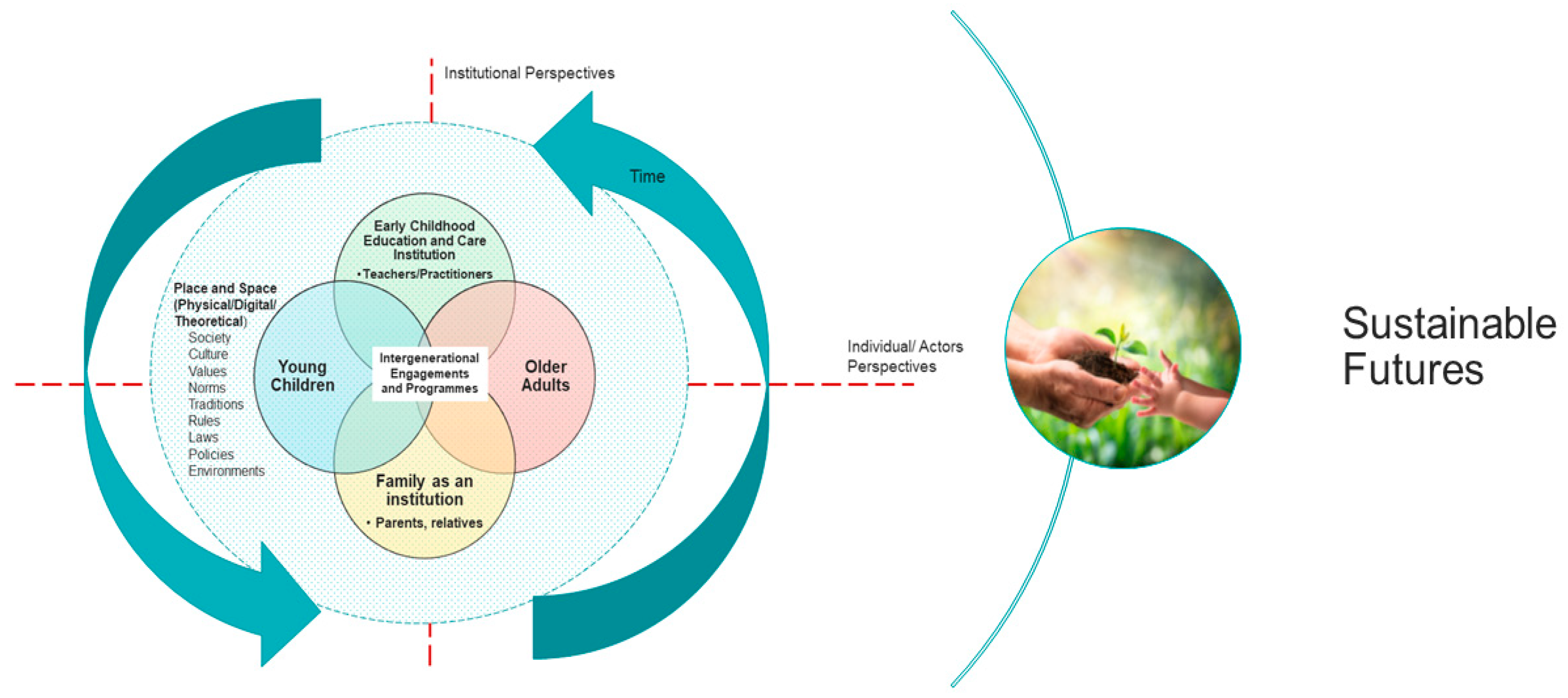

3. A Visual Representation of Elements of Intergenerational Programmes in Kindergartens

3.1. Individual Perspectives: Young Children and Older Adults

3.2. Institutional Perspectives: ECEC Institutions and the Family

3.3. Societal Perspectives: Physical, Digital and Theoretical Places and Spaces

3.4. Time

3.5. Congruent and Conflicting Elemental Overlaps

4. Discussion: Intentional Inclusion of Intergenerational Programmes towards Social Sustainability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barranti, C.C. The Grandparent/Grandchild Relationship: Family Resource in an Era of Voluntary Bonds. Fam. Relat. 1985, 34, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.; de la Fuente Anuncibay, R. Intergenerational Grandparent/Grandchild Relations: The Socioeducational Role of Grandparents. Educ. Gerontol. 2007, 34, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agate, J.R.; Agate, S.T.; Liechty, T.; Cochran, L.J. ‘Roots and Wings’: An Exploration of Intergenerational Play: Research. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2018, 16, 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, H. Play in Three-Generational Families: A Tapestry of Children’s Cultural Development. In Proceedings of the Diversities in Early Childhood Education Conference, Strausbourg, France, 26–29 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Monk, H. Intergenerational Family Dialogues: A Cultural Historical Tool Involving Family Members as Co-Researchers Working with Visual Data. In Visual Methodologies and Digital Tools for Researching with Young Children; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOY Consortium. Reweaving the Tapestry of the Generations: An Intergenerational Learning Tour through Europe; TOY Consortium: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; Available online: http://www.toyproject.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Summary-English.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Rye, J.F. Leaving the Countryside. Acta Sociol. 2006, 49, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Social Report 2020: Inequality in a Rapidly Changing World. United Nations. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/02/World-Social-Report2020-FullReport.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Newman, S. History and Current Status of the Intergenerational Field; Generations Together Publications, Pittsburgh Univ Center for Social and Urban Research: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hagestad, G.O. The Book-Ends: Emerging Perspectives on Children and Old People; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. The Sandwich Generation. Elder Care 2004, 712, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachantoni, A.; Evandrou, M.; Falkingham, J.; Gomez-Leon, M. Caught in the Middle in Mid-Life: Provision of Care across Multiple Generations. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 1490–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ødegaard, E.E.; Hedegaard, M. Introduction to Children’s Exploration and Cultural Formation. In Children’s Exploration and Cultural Formation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. Examining Early Childhood Education through the Lens of Education for Sustainability. In Research in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: International Perspectives and Provocations; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson, I.P.; Kaga, Y. The Contribution of Early Childhood Education to a Sustainable Society; Unesco Paris: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training. Framework Plan for Kindergartens: Contents and Tasks. Norway. 2017. Available online: https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Oropilla, C.T. Spaces for Transitions in Intergenerational Childhood Experiences. In Childhood Cultures in Transformation; Ødegaard, E.E., Borgen, J.S., Eds.; Brill|Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 74–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj-Blatchford, J.; Pramling-Samuelsson, I. Education for Sustainable Development in Early Childhood Care and Education: An Introduction. In International Research on Education for Sustainable Development in Early Childhood; Siraj-Blatchford, J., Mogharreban, C., Park, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Boldermo, S. Education for Social Sustainability. Meaning Making of Belonging in Diverse Early Childhood Settings. Ph.D. Thesis, PhD Programme in Humanities and Social Sciences, The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. “What Is Social Sustainability? A Clarification of Concepts”. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOY Consortium. Intergenerational Learning Involving Young Children and Older People; The TOY Project: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; Available online: http://www.toyproject.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Summary-English.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Cartmel, J.; Radford, K.; Dawson, C.; Fitzgerald, A.; Vecchio, N. Developing an Evidenced Based Intergenerational Pedagogy in Australia. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2018, 16, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanen, L. Generational Order. In The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard, M.; Fleer, M. Studying Children: A Cultural-Historical Approach; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard, M. Children’s Perspectives and Institutional Practices as Keys in a Wholeness Approach to Children’s Social Situations of Development. In Cultural-Historical Approaches to Studying Learning and Development: Societal, Institutional and Personal Perspectives; Edwards, A., Fleer, M., Bøttcher, L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. Handb. Child. Psychol. 2007, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, B. The Cultural Nature of Human Development; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ødegaard, E.E. Dialogical Engagement and the Co-Creation of Cultures of Exploration. In Children’s Exploration and Cultural Formation; Hedegaard, M., Ødegaard, E.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ødegaard, E.E. Reimagining “Collaborative Exploration”—A Signature Pedagogy for Sustainability in Early Childhood Education and Care. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky. Volume 5. Child. Psychology; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. Prologue to the English Edition. In The Collected Works of Ls Vygotsky; Rieber, R.W., Carton, A.S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, M.M.; Holquist, M.; Emerson, C. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1981; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. The Development of Higher Forms of Attention in Childhood. In The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology; Wertsch, J.V., Ed.; M. E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Minick, N. The Development of Vygotsky’s Thought: An Introduction. In The Collected Works of Ls Vygotsky; Rieber, R.W., Carton, A.S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. The Problem of Age, Transcribed by Andy Blunden. Collect. Works LS Vygotsky 1998, 5, 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff, B.; Sellers, M.J.; Pirrotta, S.; Fox, N.; White, S.H. Age of Assignment of Roles and Responsibilities to Children. Hum. Dev. 1975, 18, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, B.; Najafi, B.; Mejía-Arauz, R. Constellations of Cultural Practices across Generations: Indigenous American Heritage and Learning by Observing and Pitching In. Hum. Dev. 2014, 57, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppens, A.D.; Silva, K.G.; Ruvalcaba, O.; Alcalá, L.; López, A.; Rogoff, B. Learning by Observing and Pitching In: Benefits and Processes of Expanding Repertoires. Hum. Dev. 2014, 57, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Socio-Cultural Theory. Mind Soc. 1978, 6, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wartofsky, M. Artifacts, Representations and Social Practice: Essays for Marx Wartofsky; Gould, C.C., Cohen, R.S., Eds.; Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wartofsky, M. Models: Representation and the Scientific Understanding; Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M. Re-Covering the Idea of a Tertiary Artifact. In Cultural-Historical Approaches to Studying Learning and Development—Societal, Institutional and Personal Perspectives; Fleer, M., Böttcher, L., Eds.; Springer Nature: Basingstoke, UK, 2019; pp. 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ødegaard, E.E. A Pedagogy of Collaborative Exploration-A Case Study of the Transition from a Monocultural Entity in National Celebration Rituals to a Multilayered Informed Pedagogical Practice. In Qualitative Studies of Exploration in Childhood Transitions: Cultures of Play and Learning; Fleer, M., Hedegaard, M., Ødegaard, E.E., Sørensen, H.V., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, in print.

- Hedegaard, M. Children’s Perspectives and Institutional Practices as Keys in a Wholeness Approach to Children’s Social Situations of Development. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2020, 26, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, M. Children’s Development from a Cultural–Historical Approach: Children’s Activity in Everyday Local Settings as Foundation for Their Development. Mind Cult. Act. 2009, 16, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, M.; Aronsson, K.; Højholt, C.; Ulvik, O.S. Children, Childhood, and Everyday Life: Children’s Perspectives; IAP: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, A.; Fleer, M.; Bøttcher, L. Cultural–Historical Approaches to Studying Learning and Development: Societal, Institutional and Personal Perspectives; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. Available online: http://wunrn.org/reference/pdf/Convention_Rights_Child.PDF (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Grindheim, L.T.; Borgen, J.S.; Ødegaard, E.E. Chapter 2 in the Best Interests of the Child: From the Century of the Child to the Century of Sustainability. In Childhood Cultures in Transformation; Eriksen, E., Ødegaard, J.S.B., Eds.; Brill|Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatlow-Golden, M.; Montgomery, H. Childhood Studies and Child Psychology: Disciplines in Dialogue? Child. Soc. 2021, 35, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uprichard, E. Children as ‘Being and Becomings’: Children, Childhood and Temporality. Child. Soc. 2008, 22, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N. Childhood and Society: Growing Up in an Age of Uncertainty; Issues in Society; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- James, A.; Jenks, C.; Prout, A. Theorizing Childhood; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Qvortrup, J. The Waiting Child; Sage Publications Sage CA: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro, W.A. The Sociology of Childhood. In Sociology for a New Century, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ødegaard, E.E. ‘Glocality’ in Play: Efforts and Dilemmas in Changing the Model of the Teacher for the Norwegian National Framework for Kindergartens. Policy Futures Educ. 2015, 14, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Gemeinschaften, G.B.E. Age and Attitudes: Main Results from a Eurobarometer Survey. Commission of the European Communities. 1993. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_069_en.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of Older Persons. Geneva. 1995. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838f11.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Falconer, M.; O’Neill, D. Out with “the Old,” Elderly, and Aged. BMJ 2007, 334, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.; Ward, C.R.; Smith, T.B. Intergenerational Programs: Past, Present, and Future; Taylor & Francis US: New York, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, N.P.; Havens, B.; Black, C. Living Longer but Doing Worse: Assessing Health Status in Elderly Persons at Two Points in Time in Manitoba, Canada, 1971 and 1983. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, 36, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.L.; Charmes, J.P.; Bouthier, F.; Merle, L. Inappropriate Medications in the Elderly. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 85, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, M.; Sanchez, M.; Hoffman, J. Intergenerational Pathways to a Sustainable Society; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, E.Y.; Waite, L.J. Social Disconnectedness, Perceived Isolation, and Health among Older Adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMIL Network. What Is Intergenerational Learning? Available online: http://www.emil-network.eu/what-is-intergenerational-learning/ (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Beth Johnson Foundation. A Guide to Intergenerational Practice. 2011. Available online: http://www.ageingwellinwales.com/Libraries/Documents/Guide-to-Intergenerational-Practice.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Airey, T.; Smart, T. Holding Hands Intergenerational Programs Connecting Generations. 2015. Available online: http://www.issinstitute.org.au/wp-content/media/.../ReportAirey-Smart-Final-LowRes.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Eurochild. How Young Children, Adults and Communities Benefit from Intergenerational Activities. 2016. Available online: http://www.eurochild.org/news/news-details/article/how-young-children-adults-and-communities-benefit-from-intergenerational-activities/?tx_news_pi1%5Bcontroller%5D=News&tx_news_pi1%5Baction%5D=detail&cHash=4300947b9b4d81ea7d432564dc05c94f (accessed on 26 March 2019).

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. Public Health Report—A Good Life in a Safe Society. Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. Norway: Solberg Government. 2020. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-19-20182019/id2639770/ (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Hedegaard, M. Analyzing Children’s Learning and Development in Everyday Settings from a Cultural-Historical Wholeness Approach. Mind Cult. Act. 2012, 19, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Prout, A. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood: Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood, 3rd ed.; Routledge Education Classic Edition; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- James, A.; Prout, A. Re-Presenting Childhood: Time and Transition in the Study of Childhood. In Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood: Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 230–250. [Google Scholar]

- Alanen, L.; Mayall, B. Conceptualizing Child-Adult Relations; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mayall, B. Towards a Sociology for Childhood: Thinking from Children’s Lives; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Garvis, S.; Lemon, N.; Ødegaard, E.E. Beyond Observations: Narratives and Young Children; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alanen, L. Childhood and Intergenerationality: Toward an Intergenerational Perspective on Child Well-Being. In Handbook of Child. Well-Being; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 131–160. Available online: https://doi-org.galanga.hvl.no/10.1007/978-90-481-9063-8_5 (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Harrison, S.; Dourish, P. Re-Place-Ing Space: The Roles of Place and Space in Collaborative Systems. In Proceedings of the 1996 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 67–76. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/240080.240193?casa_token=Ceb7YhPn9lcAAAAA:alKIAh4Y5XNVJTfiSs1zLaI4TST-G3HEq6vRFnOPS0zopHhvXFrw7tVUUd8iovHgktnmAOgcVAhrHQ (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Smahel, D.; Machackova, H.; Mascheroni, G.; Dedkova, L.; Staksrud, E.; Ólafsson, K.; Livingstone, S.; Hasebrink, U. EU Kids Online 2020: Survey Results from 19 Countries. 2020. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/assets/documents/research/eu-kids-online/reports/EU-Kids-Online-2020-March2020.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Holloway, D.; Green, L.; Livingstone, S. Zero to Eight: Young Children and Their Internet Use. 2013. Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/52630/1/Zero_to_eight.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Lansdown, G. Every Child’s Right to Be Heard: A Resource Guide on the Un Committee on the Rights of the Child General Comment No. 12; Save the Children/United Nations Children’s Fund: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arpino, B.; Pasqualini, M.; Bordone, V. Physically Distant but Socially Close? Changes in Intergenerational Non-Physical Contacts During the Covid-19 Pandemic among Older People in France, Italy and Spain. Eur. J. Ageing 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.; Levy, B.R.; Wahl, H.W.; Tesch-Romer, C.; Ayalon, L.; Rothermund, K.; Neupert, S.D.; Chasteen, A. Aging in Times of the Covid-19 Pandemic: Avoiding Ageism and Fostering Intergenerational Solidarity. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 76, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, M.; Suitor, J.J.; Rurka, M.; Silverstein, M. Multigenerational Social Support in the Face of the Covid-19 Pandemic. J. Family Theory Rev. 2020, 12, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploettner, J.; Tresseras, E. An Interview with Yrjö Engeström and Annalisa Sannino on Activity Theory. Bellaterra J. Teach. Learn. Lang. Lit. 2016, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widom, C.S.; Wilson, H.W. Intergenerational Transmission of Violence. In Violence and Mental Health; Lindert, J., Levav, I., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, A.; Romano, A. Deterministic Modeling in Scenario Forecasting: Estimating the Effects of Two Public Policies on Intergenerational Conflict. Qual. Quant. 2015, 52, 2345–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckfield, J. Rising Inequality Is Not Balanced by Intergenerational Mobility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPrete, T.A. The Impact of Inequality on Intergenerational Mobility. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2020, 46, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ødegaard, E.E.; White, E.J. Bildung: Potential and Promise in Early Childhood Education. In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippine Statistics Authority. 2015 Facts on Senior Citizens. Republic of the Philippines. 2015. Available online: https://psa.gov.ph/system/files/2015%20Fact%20Sheets%20on%20Senior%20Citizen_pop.pdf?width=950&height=700&iframe=true (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Oropilla, C.T.; Guadana, J.C. Intergenerational Learning and Sikolohiyang Pilipino: Perspectives from the Philippines. Nord. J. Comp. Int. Educ. in review.

- Boldermo, S.; Ødegaard, E.E. What About the Migrant Children? The State-of-the-Art in Research Claiming Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 17 December 2018: Follow-up to the Twentieth Anniversary of the International Year of the Family and Beyond. 2019. Available online: http://www.familyperspective.org/undocs/ARES731442018.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Clark, H.; Coll-Seck, A.M.; Banerjee, A.; Peterson, S.; Dalglish, S.L.; Ameratunga, S.; Balabanova, D.; Bhan, M.K.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Borrazzo, J.; et al. A future for the world’s children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 395, 605–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oropilla, C.T.; Ødegaard, E.E. Strengthening the Call for Intentional Intergenerational Programmes towards Sustainable Futures for Children and Families. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105564

Oropilla CT, Ødegaard EE. Strengthening the Call for Intentional Intergenerational Programmes towards Sustainable Futures for Children and Families. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105564

Chicago/Turabian StyleOropilla, Czarecah Tuppil, and Elin Eriksen Ødegaard. 2021. "Strengthening the Call for Intentional Intergenerational Programmes towards Sustainable Futures for Children and Families" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105564

APA StyleOropilla, C. T., & Ødegaard, E. E. (2021). Strengthening the Call for Intentional Intergenerational Programmes towards Sustainable Futures for Children and Families. Sustainability, 13(10), 5564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105564