1. Introduction

Buddhism originated in the Indian subcontinent and spread across the globe over the centuries, making it a world religion. Ironically, in present-day India and Nepal, which possess the largest repository of sacred places related to Buddha, the number of Buddhist followers is fairly small [

1]. Here, most Buddhist religious sites are archeological in nature, and if Buddhism is to be revived, then these places need to offer Buddhist activities. It is within this context that one must study Buddhist heritage. Noticeable efforts have been undertaken to revive and rebuild the Buddhist sacred landscape in India and Nepal in the last few decades. On the one hand, governments have focused on excavations to reveal more and more archaeological evidence regarding the expanse of Buddhism [

2,

3]. On the other hand, the Indian and Nepalese governments pursued the policy of cultural diplomacy and appealed to their neighboring countries with larger Buddhist populations for help [

1]. These governments invited Buddhist associations from across the borders to come and rejuvenate the Buddhist landscape [

2,

4]. How would these transnational religious organizations work in reviving Buddhism, how would they interact with local communities, how would they negotiate national and international frameworks within which they operate, what would they make of the sacred land of Buddha, and what kind of heritage will they conserve, produce, and promote? These are some of the questions that this paper grapples with.

Millions of Buddhist followers travel to at least four important pilgrimage sites related to Buddha’s life: Lumbini, where Buddha was born, Bodhgaya, where he attained enlightenment, Sarnath, where he delivered the first sermon, and Kushinagar, where he breathed his last. Lumbini and Bodhgaya were declared as UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1997 and 2002 respectively; Sarnath is in the process of being listed as one. All these sites have recorded an enormous increase in visitors, both domestic and international. This increase is because transnational Buddhist organizations are increasingly mainstreaming Buddhist teachings and philosophies to non-Buddhists, for their universal values, and inspiring them to visit places related to Buddha [

5]. The purpose of this paper is to further the study of heritage and tourism in places where these processes are heavily influenced by transnational religious networks and their intersections with local communities. The findings presented in this paper are based on the fieldwork conducted in Lumbini in December 2019 that involved 20 interviews with major stakeholders, including the monks and managers of international monasteries, community leaders, hoteliers, tour agencies, residents, and government officials. The semi-structured interviews were conducted in the Hindi language, which is quite widely spoken in this part of Nepal where it shares a boundary with India. They were conducted in the choice of venue suggested by the interviewee, to make them comfortable. The interviewees were selected through a snowball method by first approaching the officials of LDT, members of the Hotel Association, and monks in monasteries. As most monks were fluent in English, they were interviewed in English.

2. Lumbini

Lumbini–the birthplace of Buddha–has a long history but its development as a pilgrim-town and place of universal heritage is relatively recent [

6,

7]. Long before the establishment of Lumbini as the birthplace of the Buddha, there was a small Hindu shrine where a sculpture of the resident goddess was worshipped. Only later was this sculpture revealed to be of the Buddha’s mother, Maya Devi, and is still venerated by many Hindus at the site. The context of Buddhist religious practice should be established here before we focus on Lumbini. All three main schools of Buddhist thought—Theravada, Newar Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism—are practiced in Nepal. The living practice of Buddhism is mainly embraced by the indigenous Newar community, and exhibits the syncretism of Hinduism and Buddhism in the matters of rituals, ceremonies, and festivals (for more on this, see Thapa, 2001 [

7]). However, two important aspects distinguish this indigenous form of Buddhist practice: the tradition of bhikkhus or Buddhist monks (this is substituted by the hereditary lineages of Buddhist priests, known as bajracharyas) and a complex social caste structure that emerged under the rule of Nepalese kings who supported Hinduism as a state religion. As a result, these communities follow the Buddhist philosophies, but adapt those in a socio-cultural framework that allows them to dispense religious duties, using the religious occupations of priests [

8]. For instance, Buddhist priests preside over the initiation ceremonies of bhikkhus, which are highly ritualized performances in their own vihāras. Another common practice is the collective singing of religious kirtans and bhajans, which is more of a Hindu practice. They perform many of these songs during their pilgrimages to Buddhist sites [

8]. Close to 9% of the population in Nepal follows Buddhism in its various forms, but the country is home to an enormous Buddhist heritage. The larger region of the Kathmandu Valley has more than 2000 Buddhist sites, including monasteries, chaityas, chortens and many other structures that can be collectively classified into three categories: dedicatory, memorial and funeral. The dedicatory shrines are Swayambhunath, four stupas around Patan, Chillan Deo in Patan, Chillan Deo in Kirtipur, Kathesimbhu in Kathmandu, Buddha Mandal in Kathmandu and Dan Deo near Deopatan in Kathmandu. In most of the dedicatory shrines, there is a monastery or vihāra attached to them. These are of historical importance and are dedicated through including various legends and traditions. The memorial shrines are the Buddhnath or Kasha Chaitya, the Rato (Red) Machhendranath in Patan, the Seto (White) Machhendranath in Kathmandu, the Manjushri shrine near Swayambhunath, and Mahabouddha in Patan. Funeral and relic shrines, which are believed to have ashes or some relics of the dead, are found all over the valley (these are often considered as of less importance in practice [

9]. The most popular of these are Swayambhunath, Boudanath, Muktinath, and Lumbini.

The significance of Lumbini for pilgrimage in contemporary times began to develop only after the historic visit by U. Thant, the then UN Secretary-General, in 1967 [

6]. A Buddhist follower, he was pained to see the condition of the place where Buddha was born. With an initiative from U. Thant and involvement of the then Nepalese monarch, King Mahendra, an ‘International Committee for the Development of Lumbini’ was formed in 1970 (this committee had representatives from 13 Asian countries, which was later expanded to 15 countries) (for details, see Bidari, 2009 [

6]). In 1972, this committee appointed the famous Japanese architect, Kenzo Tange, to design a master plan for Lumbini. The master plan was approved jointly by that committee and the Nepalese king. The Nepalese government then established the Lumbini Development Committee to implement the master plan, with its first task being the acquisition of land covered under the master plan. In 1985, this committee was formally instituted as the Lumbini Development Trust (LDT) under the Lumbini Development Trust Act. LDT is responsible for the overall development of the site. For various reasons (such as geopolitical tensions with its neighbors, China and India, and its religious orientation as a Hindu kingdom), it was not until the early 1990s that Lumbini began to receive some serious attention from the Nepali state [

10].

The Lumbini master plan covers an area of 4.5 sq. miles, and is divided into three sections; through the north-south axis, there runs a long body of water (see

Figure 1). The first part is the “sacred garden”, which contains the main Maya Devi temple, ancient monuments and ruins, the Ashoka Pillar, a body of water, and several small stupas. To recreate the serene, peaceful, and spiritual environment as imagined during Buddha’s time, this zone has limited construction and is segregated from other parts via a circular levee [

11,

12].

The second part, called the “monastic zone”, was designed to cater to the needs of the different schools within Buddhism. It is divided into 42 plots, where Buddhist organizations from different countries could build their monasteries and temples: 13 plots were allotted for the Theravada branch, and 29 for the Mahayana monasteries. The design of the monasteries was to follow the architecture and aesthetics of the native country alongside their own cultural traditions, so that Lumbini could be a diverse and multicultural place of faith. An official from the LDT emphasized that “only two types of designs are permitted: vernacular and Buddhist style”. At present, eight monasteries have been constructed in the Eastern Monastic zone: the Royal Thai Monastery, Thailand; the Canadian Engaged Buddhism Association (Bodhi Institute Monastery and Dharma Center) (under construction); the Mahabodhi Society Temple of India; the Nepal Theravada Buddha Vihar (under construction); the Cambodian Temple, Cambodia (under construction); the Myanmar Golden Temple, Myanmar; the International Gautami Nuns Temple, Nepal; and the Sri Lankan Monastery, Sri Lanka. On the other side (west), 14 monasteries belonging to the Mahayana traditions have been built: the Ka-Nying Shedrup Monastery (Seto Gumba); the Urgen Dorjee Chholing Buddhist Center, Singapore; the French Buddhist Association, France; the Great Lotus Stupa (Tara Foundation), Germany; the World Linh Son Buddhist Congregation, France; the Japanese Monastery, Japan (under construction); the United Tungaram Buddhist Foundation, Nepal; the Thrangu Vajra Vidhya Buddhist Association, Canada; the Vietnam Phat Quoc Tu, Vietnam; the Geden International Monastery, Austria; the Chinese Monastery, China; the Dae Sung Shakya Temple, South Korea; the Drubgyud Chhoeling Monastery (Nepal Mahayana Temple); the Dharmodhaya Sabha, Nepal (Swayambhu Mahavihara); the Karma Samtenling Monastery, Nepal; and the Manang Samaj Stupa, Nepal. In addition, there are three meditation centers.

The third part of the site, the cultural center, was envisioned to be a place of cultural exchange between Buddhist followers from different countries. With only three major buildings constructed, this vision is far from realized. The existing buildings include the museum, the auditorium (financed by the National Committee for the Development of Lumbini in the United States), and the Lumbini International Research Institute (LIRI), gifted by the Reiyukai movement of Japan and operated by German scholars. Toward the end of this zone is the proposed New Lumbini Village, which would be a place for the hustle and bustle of visitors, offering a range of accommodation facilities and opportunities for interaction with the local community.

Given its importance as the birthplace of Buddha, Lumbini was declared a World Heritage Site in 1997 on the following criteria:

Criterion (iii): As the birthplace of the Lord Buddha, testified by the inscription on the Ashoka pillar, the sacred area in Lumbini is one of the most holy and significant places for one of the world’s great religions.

Criterion (vi): The archaeological remains of the Buddhist vihāras (monasteries) and stupas (memorial shrines) from the 3rd century BC to the 15th century AD, provide important evidence about the nature of Buddhist pilgrimage centers from a very early period. (

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/666/ accessed on 20 February 2021)

The promise of the comprehensive development of Lumbini as per the master plan is still to be fulfilled in its entirety [

12]. In this sense, Lumbini presents an excellent case of how living heritage is to be recreated from an archaeological base, using support from international religious and cultural organizations.

3. Co-Creation of Heritage: International Monasteries

In Lumbini, pilgrims are most interested in visiting the Maya Devi temple, where they can see the marker stone that commemorates the birthplace of Buddha. Visitor movement is heavily restricted inside the temple, as it also houses archaeological remains. Consequently, visitors are required to walk on wood platforms/boardwalks along the perimeter, and cannot perform any rituals except for the seeing (darshan) of the marker stone. However, much to the disappointment of archaeologists, there is a “donation box” for pilgrims to offer cash near the marker stone (making an offering is an essential part of pilgrimage). Most of the pilgrimage-related rituals take place outside in the surrounding garden, where they bow to the Ashoka pillar and visit Pushkarini Lake, the bodhi tree and votive stupas, and undertake circumambulation of the sacred garden [

3]. It is here that most devotional activities take place, including prayers, meditation sessions, and community performances (see

Figure 2).

Beyond the sacred zone, it is the monasteries that form the main hub of activities. As mentioned in the previous section, many international monasteries have been built by transnational religious organizations. In principle, monasteries are required to perform multiple functions: providing space for worship, the lodging and boarding of monks and pilgrims, organizing sermons and discourses, retreats, etc. As such, they have a temple, prayer hall, rooms for monks and pilgrims, a dining hall, reception, and other supporting facilities on their premises (see

Figure 3, showing the Thai monastery). This was clearly explained by the head monk at the Swiss monastery in Lumbini: “We follow the core teachings from Atisha Dipankara… the design of the monastery is based on symbolism… our purpose is to teach kids and other western seekers in Tibetan Buddhist philosophy… and maintain discipline as is [done] in our parent monastery that is in Switzerland”. A similar emphasis on teaching is found in almost all monasteries. Some monasteries also engage in social work in the local community, but the primary purpose remains to serve the pilgrims from their native countries (interview with the head monk, the Thai Monastery).

Most international monasteries have resident monks, and their activities range from the teaching of Buddhist literature, the training and ordination of monks, providing spiritual counsel to seekers, offering sermons and spiritual retreats, and organizing the visit of pilgrims to the Maya Devi temple. Monks guide the worship rituals at their own temple—these are exclusively for pilgrims from their home countries. Those pilgrims who stay at monasteries must follow rigorous schedules as prescribed by the monks, including early morning meditation, the offering of pujas twice a day, and observing strict diets and religious behavior (interview with the head monk, the Thai Monastery). Such behavior was expected from pilgrims staying in other monasteries also, but lay guests were exempt from such routines. The monasteries provide a religious-spiritual environment for their pilgrims, and as such are involved in the co-creation of the heritage [

13]. For instance, the manager at the Korean monastery boasted about a “Korean-style puja”, and the head monk at the Thai monastery talked about benefits and merit-making for Thai pilgrims who follow the rigorous daily routines when they stay in the monastery. The head monk at the Swiss monastery reiterated, “Just [a] building cannot create atmosphere… the place and its spirit comes from people and gets magnified… people working here (guards, officers) cannot provide sacred meaning… it has to come from Buddhist practitioners, otherwise it is difficult to maintain sacredness.” This lending of a Buddhist atmosphere comes from the regular flow of monks and pilgrims in the monasteries. A local guide also observed that “the spiritual ambiance in monasteries is better for pilgrims”.

While the activities of long-term residents make monasteries a spiritual abode, their “exoticism” and “otherness” have also become attractions for non-Buddhists, and lead to the huge popularity of Lumbini as a tourist destination.

4. Visitation Patterns: Pilgrims, Tourists, and the In-Betweens

This section provides a nuanced understanding of visitation patterns in Lumbini. These patterns were identified based on the data collected from the Lumbini Development Trust during the fieldwork.

In 2018, Lumbini received an estimated 1.17 million visitors, of which 76% were Nepalese, and 12.6% were Indian. The remaining 11.4% (about 170,000 visitors) were foreigners. These numbers are almost three times those that were recorded in 2011 (see

Figure 4). However, growth has been different for each of these demographics during this period: while there was little increase in the number of foreigners (about 36%), Indian and Nepalese visitor numbers registered dramatic growth (230% and 200%, respectively). The data suggest that although the initial volume of Nepalese and Indians visitors was low a decade ago, it is now growing at a considerably rapid pace.

A closer examination of visitor numbers across different months suggests that their visits are related closely to the holiday season.

Figure 5 shows that the peak numbers of Nepalese and Indian visitors are during the April–May summer holidays and November-December festival period. The foreign visitors, however, are visiting in large numbers across six months—October to March—with peaks in December and January. These are also the times when they are visiting other sites in the Buddhist pilgrimage circuit across the border in India.

The data on foreign visitors shows some interesting trends. LDT started recording foreign arrivals in 1996 (Lumbini was declared a WHS in 1997). Since then, from a small base of about 25,000 foreigners per year, the numbers have grown to more than 175,000 per year in 2018. In 1996, foreigners came from about 21 countries, but now they come from more than 113 countries (

Figure 6).

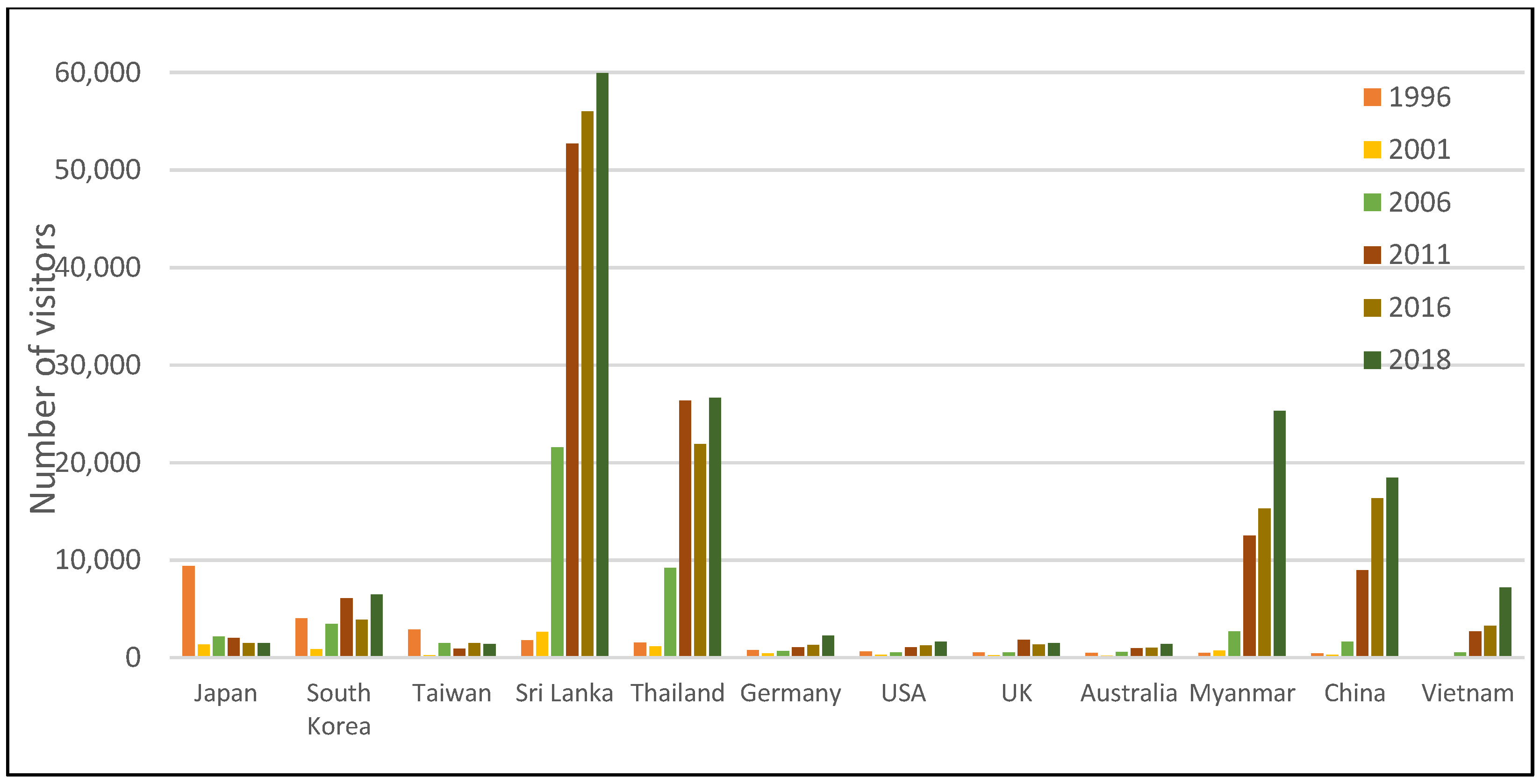

Amongst these “foreigners”, visitors from Buddhist countries continue to dominate the numbers (see

Figure 7). In order of magnitude, these are Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, China, Vietnam, South Korea, Japan, and Malaysia. It must be noted that in the early years, visitors from Japan, Korea, and Taiwan constituted the largest proportion of foreigners. Such numbers can be easily related to the fact that these countries have monasteries in Lumbini—which means that visitors will have some assurance of finding lodging and boarding and that their visits will be fruitful.

Visitor Behaviour

From the statistics on visitors, a few observations can be made. First, the lower numbers of international visitors are most likely coming in as pilgrims. They undertake the necessary ritual practice, offer prayers, meditate, perform prostrations and circumambulation. Most markedly, their appearance and their activities speak of their religious motivation to visit Lumbini. This observation resonates with the findings of a recent visitor survey conducted by LDT, where it was found that “17% explicitly called themselves pilgrims… the majority of visitors were domestic… the package tour was the mode of travel for the lowest number of visitors” and so concluded that Lumbini is “a destination for tourists” [

14].

Second, it is quite unlikely that the large numbers of domestic visitors are religiously motivated pilgrims, because the numbers do not correspond with the minority population of Buddhists in Nepal. A similar scenario might be the case with visitors from India. Most of these are thus interested in Lumbini as a tourist attraction. These observations can also be supported by examining visitor behavior. A senior monk clearly makes the distinction: “Pilgrims have a mission/purpose; they need to see the birthplace of Bhagwan (Buddha)…Others are guests or tourists…” Some of the popular activities in which tourists engage are boating on the lake (see

Figure 8), taking pictures of the exotic culture exhibits, and posing in front of the massive idols and eclectic statues of Buddha in the international monasteries. For many, the native architecture of monasteries itself is an exotic experience.

These observations seem to be a continuation of some of the findings reported by Coningham et al. in their study of visitors in 2002.

In terms of the amount of time spent on the site, 68% of visitors spent less than 30 min at the site of the sacred garden. Between 60 and 70% of visitors had visited the site previously, with only between 40 and 30% making their first visit. It was most notable that between 64 and 81% of visitors did not stay overnight in Lumbini, which partially explains the reason for the low amount of time spent at the site itself by visitors. Buddhists and Hindus formed the largest identifiable religious affiliation of visitors, with Nepalese citizens representing the largest numbers of visitors to the site representing between 49 and 75% [

3].

It must be noted that between the two poles of pilgrims and leisure-tourists are the in-betweeners, who may be motivated by religious reasons, but they may not be fully aware of the Buddhist heritage that they are visiting or partaking of. This is most evident in the way that neo-Buddhists tour the Chinese, Thai, Korean or other monasteries that are religiously and culturally different from their own path of Buddhism. Increasingly, large numbers of neo-Buddhists are traveling on the Buddhist pilgrimage circuit, and as a part of that circuit, visit Lumbini. For them, it is their tour leader who tells them where to visit and what to do. Interestingly, we find neo-Buddhist pilgrims from India praying and making offerings to a Chinese Buddha (see

Figure 9).

Often, groups of international pilgrims come with their own guides (who may be from their home countries or hired in the place from where they start their tour). A range of guides can be hired, but all of these are external to Lumbini: those who are Buddhist teachers and organize tours; commercial tour operators who hire local guides; monks accompanying pilgrim groups that they would have mobilized from their home countries; and sometimes, monks that volunteer at the international monasteries. According to field interviews, hardly any guides are available in the sacred garden complex. An LDT official confirmed that “there is an association of guides, but it has only 18 members, and of those, only 5–6 are working full time.” Even the Nepal Tourism Board, the state agency that has been rigorously promoting Lumbini as a tourism destination [

10], does not have an information kiosk in Lumbini. It seems that the interpretation of Buddhist heritage is left to the visitors.

The opportunities for interpretation and understanding of this heritage are to some extent constrained by the design of the master plan. In the “Sacred Garden Master Plan” area, vehicular movement is restricted, and this means that most visitors must walk. When in a group, walking the 4–5-km distance without many stops or attractions is a challenge. Thus, most day-trippers can visit only the Maya Devi temple. Some groups visit the Chinese and Korean monasteries because of their proximity within the western zone. Others combine visits to the Thai and Sri Lankan Monasteries in the eastern zone. Access to the Master Plan area is controlled via two gates that are miles apart and in different directions. This means that once in the sacred garden area, it is difficult for visitors to leave, and they cannot freely access accommodations that are outside the sacred garden area.

While most international pilgrims support the monasteries, it is the domestic tourists that have driven the demand for a tourism infrastructure. For many years, there were only a handful of hotels in Lumbini: the first was built inside the master plan area by a Japanese agency in 1990, and that catered mainly to a Japanese clientele. Over the last few years, hotels have multiplied outside the master plan area—mainly around the gates. At present, there are about 80-plus hotels that can be categorized as: (a) 5 that are three- and four-star; (b) 10 that are economy-class; (c) 40 that are budget-class; (d) the remaining are general guesthouses, which include dormitories that can be used mainly for group accommodation (5–10 occupants per room) (interview with the president of the Lumbini Hotel Association). The prevailing trend is that “foreigners stay for at least two nights; domestic tourists and pilgrims, just one night” (hotel owner, Lumbini). A large proportion of group tours come to Lumbini from across the Indian border, which is just 40 km away, and hence would generally wrap up a day visit and travel back to their accommodation on the Indian side. Although hotel numbers are increasing, other supporting tourism infrastructure, such as local transport, tours, restaurants, hospitality services, is not yet developed in this largely rural landscape.

5. Co-Creation, Imported Buddhism, and Multiple Heritages

The co-creation of Buddhist heritage by international monasteries must also be recognized in relation to its context [

13]. Lumbini is a part of a large archeological landscape which in turn is surrounded by a rural hinterland. A large proportion of its population is in agriculture-related occupations and is predominantly non-Buddhist: about 65% of the population in the surrounding villages of Lumbini is Muslim (interview with the Mayor, Lumbini Cultural Municipality). This context has a strong bearing on not only the visualization of Lumbini as a World Heritage Site but also its development and management as an important heritage site with the potential to attract tourists. One, the physical development is restricted by national laws related to managing and maintaining such archaeological sites, and the decisions of national authorities. Two, such an archaeological Buddhist heritage is different from the practices of the dominant social-cultural groups, and that means a lack of interest in valuing it as their own [

3,

15].

The sacred garden of Lumbini, as the birthplace of the Buddha, is the main component of Buddhist heritage. This archaeological landscape is brought to life by different Buddhist groups as they engage with the sacred landscape, through rituals and performances that are embedded in their traditions from their homelands. Through those rituals, they understand, mediate, and realize the sanctity of the sacred garden. As such, one can find many ways of veneration that may be native to some but would appear “exotic” to other groups.

Buddhist pilgrims from different countries and different paths interact and engage with the sacred landscape of Lumbini in a variety of ways. While the opportunity to be in direct contact with the sacred object—the marker stone—for a longer duration and to make offerings are limited due to conservation requirements, these are fulfilled by performing rituals in the garden. The same landscape then provides multiple points of interpretation of this heritage. The multiple interpretations and the diversity of Buddhist heritage are also co-created by international monasteries as they follow their own native traditions. Even in the layout of the site, the distinction between the two schools of thought of Buddhism is maintained, so that each can follow their own rituals, meditation techniques, prayers, etc.—this is something that Geary has called “ritual demarcation”. So, for a pilgrim, visiting Lumbini can be an enriching experience as he/she has the possibility of being exposed to the living practice of Thai Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Sri Lankan Buddhism, Burmese Buddhism, and so on, which are on display in the international monasteries. The ways in which various strands of Buddhist heritage are interpreted add to the universal value of Lumbini as a world heritage site. For instance, “On the full moon night, all monasteries come together for prayers at the Maya Devi temple, and that shows how we are all bound by our devotion to Buddha,” (head monk, Swiss Monastery). Besides the spiritual and religious aspects of this heritage, it is the cultural exoticism of monasteries that provides a major resource for interpretation and tourism.

As part of the master plan, monasteries were to follow their nationalist or vernacular Buddhist designs. Such directions as related to native designs and aesthetics were followed. For instance, the Royal Thai Monastery (popularly known as Thai-wat), with its marble temple and vernacular style, set an example for the other Thai monasteries that were to be built later. Many monasteries have fascinating pagodas, gardens, and large-scale sculptures such as the Great Buddha statues, and all this creates a sense of attraction for visitors. The monasteries and their temples mimic what Geary observed in the case of Bodhgaya, where they serve as “opulent and lavish religious landmarks” and “present a pronounced spatial and visual counterpoint to the rural landscape, and project an image and presence of international Buddhism onto the surrounding geography [

4]”. He further argues that “the colorful global landscape of foreign temples and monasteries” [

4] is a big draw for domestic tourists.

The use of monasteries as tourist attractions in Lumbini is reflected in terms such as “pleasure park”, “amusement park”, “open-air museum”, and “picnic spot” that recurrently appeared in the interviews. Many monasteries and temples provide a backdrop for photo opportunities. A senior archaeologist remarked that the “monastic zone” has become “temple zone” where “Nepali local tourists do not even spend five minutes; they are interested only in taking photos in front of the temple and move to the next; they often have their back to Buddha-how can they even know spirituality… monasteries are losing their value.” This is clearly seen in

Figure 10. A senior monk of the Nepal Monastery lamented, “Hardly any pilgrims… Only fun lovers…”. The increased presence of domestic tourists was highlighted by a local tour guide, “More than 80% are Nepalese and Indian; rest are foreigners; out of Nepali visitors only 10% are pilgrimage-tourists rest 90% are for bhraman (tourism)”. The rapid increase of domestic tourists in Lumbini coincides with the increasing number of attractive Buddhist temples that have been built in recent years (interview with local media reporter).

Thus, international monasteries present a religious-recreational mix, wherein there are many interpretations of heritage. While most tourists would be happy to see an exotic Buddhist heritage from another country that may be different from their own, there are questions about what is authentic and whether it is really in alignment with the values of Buddhism. Of some of the monasteries, one monk remarked: “A building cannot create atmosphere; the place–spirit comes from people and then gets magnified… how can people working there (guards, officers) provide sacred meaning… they have no idea of “welcoming” and guiding, so it is difficult to maintain the sacredness of a pilgrimage site.” The religious and spiritual motivation of Buddhist pilgrims and the leisure-orientation of visitors reinforce these concerns about sanctity.

It is just not the sanctity, but also the social-cultural construct of Buddhism that has a strong bearing on articulating Lumbini’s heritage. These concerns are encapsulated through a construct—imported Buddhism. I heard this phrase from a hotelier who was born in Lumbini, and I was both surprised and taken aback. With pride, he said, “I am born in the place where Buddha was born, so I grew up knowing Buddhism.” Soon, he followed with a certain disappointment, “what I see now is Imported Buddhism”. This term resonates with most things that are developed in Lumbini. Geary’s interpretation of Bodhgaya as a “place of multiple Buddhism(s), where national, sectarian, and cultural-linguistic differences undercut a singular conception of the religion” [

4] may well also be true for Lumbini, but it is very clear that in the perceptions of the local communities, these are still different from their own brand of Buddhism. From their perspective, international Buddhist paths and schools are interested in pursuing their own agenda. The plethora of diverse rituals, performances and ceremonies performed by transnational organizations in these places provide the “other dimensions”—mainly that of spectacle—but these are hardly embraced by local communities. In these spectacles, the local communities are service providers of menial tasks rather than participants and owners of the Buddhist heritage.

6. Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Tourism in Lumbini

In Lumbini, the Maya Devi temple marks the place of Buddha’s birth and is venerated by all Buddhists. Besides this shared heritage, as the above findings suggest, it is the monasteries that are co-creating Buddhist heritage as a resource for tourism, by being attractions and providing for pilgrims. As such, they have emerged as important stakeholders in religious tourism. Moreover, the master plan has provided the spatial context for an understanding and appreciation of such co-created heritage. This externally driven creation of heritage in a WHS has significant implications for the sustainability of tourism, and its benefits for the local community.

6.1. Heritage and Tourism Management at Lumbini as WHS

Initiated and supported by the UN, Lumbini is almost a display center for the international monasteries. So, right from the start, it has been a designed environment to preserve the historical birthplace of Buddha and to enliven the universal religion. So, there are two major stakeholders: Lumbini Development Trust and the international monasteries.

The Lumbini Development Trust was established to implement the master plan, and thus has complete control over what happens in the master plan area. Since its inception, the Lumbini master plan has been mainly funded by external sources such as the state government and international agencies, UNESCO, and bi-lateral funds. Unlike other religious sites, where pilgrim donations are a primary source of revenue, the Maya Devi temple hardly derives any income from the visiting pilgrims, because making offerings in the main temple is quite difficult since it is an archeological site, and there is limited space for movement in front or around the nativity marker. In the past, a donation box was kept by a monastery for offerings. In 1995, LDT took over this box and started to collect cash for improvements at the temple, but this is highly contested by archaeologists (interview with a former senior archeologist). Coningham et al., in their study, found that “the Pillar and Temple are now beginning to be provided with clear ritual focus areas for lamps and offerings, so as to reduce damage to the monuments themselves” [

3]. LDT collects entrance fees of RP 500 from foreigners, RP 300 from visitors from SAARC countries, and only 10 RP from Nepalese visitors. It is not hard to imagine that when foreign visitors constitute less than 10% of visitor flow, this income is not substantial, and LDT is struggling to maintain the facilities and amenities in the master plan area (interview). As per the master plan, vending is allowed only in the bus-park area near one of the entrance gates. LDT has constructed and leased 34 permanent shops here. In addition, it has registered about 150 vendors to operate around this area, for which opportunity they pay daily fees and monthly rent. Given these limited sources of revenue, LDT has to rely on external sources of funding. For instance, it is mainly owing to a major Asian development bank-funded project that some major improvements were undertaken in Lumbini, including the “construction of a visitor center, and landscaping and pedestrian walkways around the center, enhancement of on-site interpretation displays and signages, development of car parking, and the bus stop and pedestrian walkway at the entry of the site” [

16]. Because of the uncertainty of government funds, LDT has taken a very long time to fully implement even the basic infrastructure necessary for the master plan, and thus Lumbini is still a work in progress.

The monastic zone in the Lumbini master plan is symptomatic of the broader cultural diplomacy at play. For reviving Buddhist sites, both India and Nepal rely heavily on cultural diplomacy, where they pride themselves as being repositories of a rich Buddhist heritage, and use this heritage to connect with neighboring countries in Asia that have large Buddhist populations [

1,

17]. One pioneering initiative from this is the land grant in Bodhgaya that was provided by the Prime Minister of India in 1957 (to mark the 2000-year celebration of Buddha Jayanti) to the Thai government. Under the name of the “Royal Wat Thai”, this became the first Buddhist monastery and temple in the post-independent era to be built under the jurisdiction of a foreign head of state [

1]. Using diplomatic ties, making land available for developing a Buddhist religious infrastructure became a mainstay in the revival of Buddhist heritage. The Lumbini master plan completely legitimizes the need for foreign monasteries to enliven its archaeological landscape.

In the master plan, international monasteries were to represent Buddhists from all over the world and bring their native religious and cultural traditions to Lumbini. To construct a monastery, the sponsoring organization has to seek approval from LDT. There are only 42 parcels of land across three sizes of plot: 80 m × 80 m; 120 m × 120 m; and 160 m × 160 m. Agreements must be created between transnational organizations, the LDT and the government, before establishing a monastery; of the total cost, monasteries must pay 5% in service fees and 10% in development charges. The organizations supporting these monasteries need to be resourceful and must have the capacity to maintain monasteries and all the religious paraphernalia for marking their presence in Lumbini. This was most clearly illustrated in the example of the Burmese monastery—the first to acquire a plot under the 99-year lease in the monastic zone, but they are yet to construct any structure (interview with senior archaeologist). Moreover, transnational organizations face the challenges of navigating through a tedious approval process at the national level, and then through the local construction and support system (manager, Chinese monastery). Acquiring a Visa to stay in the country is a challenge for monks, and this has a strong bearing on the functioning of monasteries. For instance, for the last 3–4 years, Korean monks were not given visas for long-term stays, and that led to a steady decline in the grand monastery, which was once very popular (manager, Korean Monastery).

There are other ways in which cultural diplomacy is used at Lumbini. One of the main activities of LDT is to host diplomatic visits. LDT facilitates visits by international dignitaries from Buddhist countries, and thereby attracts more Buddhist followers from those countries. In 2018, certain notable visitors were the President of Sri Lanka, His Excellency Maithripala Sirisena, and the President of Myanmar, His Excellency U. Win Myint. Their entourage included high-level diplomats. In addition, LDT invites many national and international dignitaries for the International Buddhist Conference, to coincide with the Buddha Jayanti Celebrations. Using the potential of international travel expos, LDT has been signing bilateral agreements with many Buddhist countries. For instance, in 2016, Lumbini signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Koya Town of Japan as a sister city in 2016. A similar MOU on a “Friendly and cooperative relationship between Lumbini Sacred Garden, Nepal, and Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic Area, China” was signed at the Leshan Tourism Expo 2018 [

5]. Lumbini’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site aids in the exercise of international cultural diplomacy, and this can be visible “in the form of the funding of conservation projects” [

5,

17].

Many monasteries, supported by their national governments, created magnificent structures that attract hordes of domestic tourists, but these flows are seasonal, and these visitors are not the ones to make donations and make merit like Buddhist pilgrims. In the Thai temple, for instance, more than 90% of its income came from pilgrim donation (interview with Head Monk), but there is hardly any income for the Korean Monastery. Its physical location within a confined sacred garden master plan area makes monasteries more isolated and provides very few opportunities for interaction with the local communities. Thus, with fewer visitors, they have to rely on their international patrons for funding. Generating and using such international funds is always the biggest challenge, and this affects how much a monastery can do in terms of producing cultural heritage. This is clearly seen when one compares the flourishing Thai monastery and the Korean monastery, which is in quite a dilapidated condition without maintenance and without monks.

Despite the challenges related to this reliance on international funding, tourism in Lumbini has picked up—and that is mainly due to the increasing flow of domestic tourists, as seen from the visitation patterns. However, for them, the interpretation of Lumbini’s heritage is as a tourist destination rather than the universally sacred place that it aspires to be. Such a tourism image is also consciously created and promoted by the Nepal Tourism Board, which Bhandari contends is “somehow contradictory” to the goals of the site to become a serene sacred site, as the master plan had envisaged [

10]. However, these tourism activities are the ones that provide some income opportunities for those staying in the villages outside the buffer zone around the master plan area [

18]. This is also evident from the increase in the population of the Lumbini municipality, which covers an area of 112.29 km

2 surrounding the master plan area: from 71,000 in 2009, it increased to about 89,000 in 2019. The local community considers itself as a part of the cultural heritage of Buddha—something that was proudly reinforced by the Mayor: “...that is why we have named our municipality Lumbini Sanskritik (Cultural) municipality” (interview with the Mayor). However, they have mixed reactions as to the functioning of international monasteries in Lumbini.

6.2. Competition from Monasteries as Tourism Enterprises

Lumbini has seen an increase in the number of hotels over the past few years, which have a direct and insurmountable competition from the monasteries. The scale of monasteries ranges from a monastery with 50–60 rooms (the Thai monastery) to about 300 rooms (the Chinese monastery). The international clientele favors monasteries, and that is where all the money is spent. The mayor of Lumbini said, “Buddhist history is recognized, and spirituality is increased… and there is no day without tourists... but foreigners [are] not giving economic benefit; local life [is] not changing and [there is] not much business”. Most economic opportunities related to tourism are concentrated on and operated by monasteries: accommodation, dining, tours, souvenirs, and so on [

19]. This means that they provide all the needed accommodation, implying a “difficult situation for local hotels and guesthouses which have very limited business opportunities” (interview with a hotelier).

Although monasteries provide the religious infrastructure essential for the pilgrimage economy [

20] of Lumbini, they continue to be perceived as outsiders by local communities and agencies that deprive them of the opportunities to engage in tourism-related occupations. This is most pronounced amongst those living just outside the master plan area in the buffer zone. Many of them were relocated when their lands were taken away—most now work in menial jobs such as cleaners, cooks, drivers, and maintenance staff in hotels and monasteries. For many hoteliers, whose hotels have low occupancy rates, this is also about survival, as pointed out by a hotelier: “the seasonality of tourists is a problem, but the monasteries pose a bigger threat, because we do not have advanced systems of booking and setup like those mighty monasteries”. Moreover, monasteries have monks and other supporting staff, who can provide the level of comfort and services that foreign tourists would be expecting. It is clear that the just-developing local hotel industry is no match for the well-established monasteries, which provide a complete package experience for the visitors. Many monasteries organize pilgrim tours in the Buddhist circuit by hiring travel agencies from other major cities, such as Delhi and Kolkata in India, and Kathmandu in Nepal. Locals are engaged in providing local services only.

Besides the religious and heritage aspects of a site, there are other supporting services that are equally crucial for a successful religious tourism economy in that particular place [

20]. In the case of Lumbini, however, most tourism-related activities (both religious and recreational) are concentrated within the master plan area. It is seen that monasteries provide complete meals and refreshments, and thus, there is hardly any need for pilgrims to go outside and eat. Religious souvenirs are another major source of revenue from visitors. Outside the Lumbini master plan area, there is not a single shop that sells souvenirs and regalia related to pilgrimage. There are only a few vending shops in the Master Plan area but “they all sell souvenirs that are made in China and India, there is nothing that is made locally even though this [is] the land of Buddha” (interview with a local guide). Overall, one can find the dominating presence of the monasteries in every aspect of the economy related to pilgrimage and religious tourism. It is also evident that the benefits that are realized from tourism for the local economy are much less in comparison to the revenues that are accrued by international tour operators and monasteries.

Residents argue that because monasteries derive benefit from the incoming pilgrims, they should be considered as economic enterprises. As per regulations, only a certain number of monks and pilgrims can stay in monasteries to maintain monastic establishments. A hotel owner in Lumbini pointed out that: “Hoteliers are not getting guests, but monastery rooms are full, and that creates [a] hostile situation; [the] master plan suggests only 11 people staying in one monastery—they should focus on [the] spiritual—and provide dharamshala [pilgrim-lodges] for low-budget travelers, Chinese monastery about 500 rooms, Korea monastery about 100 rooms”. Somehow, rules are not enforced strictly for the monasteries. The senior archaeologist lamented that the “monastic zone was for the meditation and practice of Buddhism, but now they have rooms and act like commercial complexes”. Moreover, in many cases, the international monasteries bypass the local rules and regulations and take the matter beyond the local administration to the national governments to get their work done via diplomatic channels.

6.3. Production of Enclaves and Hollowed Spaces

The designed environment of Lumbini has created what is known in tourism literature as enclaves. The pilgrims who visit Lumbini are confined to their monasteries, which is where they stay, take meals, and pray. Access to the monasteries in the master plan area is controlled via two gates that are miles apart and in different directions. This means that once in the master plan area, it is difficult for visitors to come out, and visitors cannot freely access facilities that are outside the sacred garden area. The rigorous routines of the monasteries, the physical separation and distance from the nearby villages, and rigid physical boundaries mean fewer opportunities for interactions between the visitors and the communities outside the complex. A guide in Lumbini explained in an interview:

“There is an ‘andar ki Lumbini’ and ‘bahar ki Lumbini’ (one Lumbini is inside and one is outside); till Lumbini goes out of the ‘3-mile’ it will not develop; how long will international organizations support the development process? 3 square mile is [the] UN’s Master Plan so what can we do? Locals have no knowledge; local stakeholders need to be involved otherwise it will lead to conflicts… Monks/religious institutions cannot do development. Outside the 1-km radius, people are still living a life that is 30 years backward.’

The sentiment that there are two worlds—one of the monasteries and one of the communities—was often repeated to me in most interviews. LDT is constrained by its own mandate to only operate within the master plan area, and has nothing to do with what happens outside. According to the mayor, “LDT does not do anything for us or even employ our people, there is no affinity with LDT; if LDT would have done something then nearby villages would have developed.” Rodriguez claims that “government representatives described the master plan policies in Lumbini as efforts to foster development”, but, in reality, “struggles over where vendors could set up shop, building and zoning regulations, and the extent of the affected areas have all been sources of conflict” [

21].

The other stakeholder, monasteries, also distance themselves through deliberate means, language being a powerful one. It was observed that monasteries exclusively used languages from their countries in their premises, with no translation offered to others. In addition, none of the monasteries reported any of their activities to the local government. They are only required to submit annual reports, but those were in their own languages and sent to their headquarters in other countries. Thus, most were not transparent. In these circumstances, it is quite easy to understand the negative perceptions of residents, when they pose questions like: “What they do behind the big walls? Only Buddha knows”. The walls and the enclaves mean that the benefits of tourism are not accrued to the local communities, but to the parent organizations, located in a foreign country.

Reader has forcefully argued that pilgrimage “is a major source of income for the people living in the vicinity of major sites” [

20]. However, in the case of Lumbini, that pilgrimage economy seems to operate within the confines of a heavily controlled master plan, and this has serious repercussions on the sustainability of the heritage context within which Lumbini exists. On the positive side, the WHS status of Lumbini has generated much interest in the international community, and that has had a positive effect on its popularity for domestic tourists as well. How to channel this potential and balance the global versus local benefit should be the focus of LDT, if Lumbini is to become a successful destination for religious and cultural tourism. It is necessary that LDT now starts to think beyond the development of infrastructure, to embark on a tourism management plan that promotes the co-created heritage of the site and accounts for the needs of both international and domestic visitors, and helps create opportunities for strengthening the participation of host communities in the tourism economy.

7. Conclusions

This paper has offered some insights on the issues around heritage and tourism management, which have a strong bearing on the sustainability of the WHS of Lumbini in Nepal. The case of Lumbini is not an isolated one, but where the global interest in universal and world heritage intersects in many different ways with the local context. These intersections are particularly important in places with a considerable heritage of archeological sites that developed around a religion in the past, but now have fewer people following that religion. This archeological heritage resource is somehow to be revived, and for this, national governments invite organizations from other countries to import their religious and cultural practices, to bring life to those sites. As such, findings from Lumbini may be applicable to many of those places related to the heritage of different religions. For instance, Rodriguez, in a comparative study, observes that both Lumbini and Bodhgaya “have become sites of contestation as pilgrimage, and monastery building has increasingly come to characterize Buddhist practice since the late nineteenth century, and as they have become epicenters of a global Buddhist sacred geography [

21].

At the conceptual level, this paper has drawn attention to the key ideas of co-creation of heritage for religious tourism in a WHS. This takes place when international monasteries superimpose and juxtapose their own traditional practices and rituals on the sacred landscape of Lumbini. They provide the necessary religious infrastructure for Buddhist pilgrims to mediate the sanctity of the place [

20], and partake in the spirit of the place where Buddha was born. A flip side of this co-creation is that it is perceived as “imported Buddhism” by local communities, as they see this juxtaposition on their environment as an import that has little to do with their own religious practice. The process of co-creation also generates tourism, because monasteries become attractions of the cultural “other”. This is further aided by the fact that the master plan was designed for a serene experience and had elements that would appeal to the different sensitivities and expectations of visitors. This religious-recreational mix then presents a new kind of heritage that needs to be interpreted, conveyed, and appreciated.

At a practical level, the paper explains that the sustainability of tourism in a WHS such as Lumbini is heavily reliant on international support and funding from external sources, because creating such a place is a massive undertaking. The revenues from other sources, such as entrance fees and the lease of shops is negligible, compared to what is required to even maintain the basic services in the master plan area of Lumbini. The other important stakeholder, the monasteries, are self-financing institutions that depend directly on pilgrims for their vitality. However, their presence in the master plan also generates consternation among the residents, who see them as competitors in the tourism economy.

In this exploratory work, many questions were answered but many more have also been raised. For example, what are the impacts of the seemingly imported Buddhism on everyday practices, rituals, and performances of native Buddhist populations? How would monasteries interact with local communities to produce more equitable benefits from the tourism economy? It also asks how Lumbini can continue to maintain its WHS status in the wake of the combined sacred and leisure orientations that might threaten to affect the sanctity of the place, and whether it will move beyond a reliance on external support for its vitality. At a broader level, it is prudent to examine how the form of tourism seen in Lumbini intersects with other forms of tourism popular in the mountainous Nepal region, and how similar or different are Buddhist pilgrimages in Lumbini to those observed in other Buddhist heritage places. Finding answers to these aspects can provide a more holistic understanding of how the value of heritage can be fully realized for improving tourism prospects in world heritage sites.