Analysis of Attendance and Speleotourism Potential of Accessible Caves in Karst Landscape of Slovakia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- 1.

- We assume the highest cave attendance in 2019 is due to the continuous increase in the number of tourists in Slovakia since 2014, culminating in 2019.

- 2.

- We expect the highest number of visitors in the most famous caves of the Western Carpathians located in national parks, namely Demänovská Cave of Liberty in the Low Tatras National Park and Belianska Cave in the Tatra National Park.

- 3.

- We assume that the approach and interpretation of the cave guide are essential factors increasing the evaluation of the attractiveness of caves in terms of the potential for speleotourism.

- 4.

- We assume a correlation between the highest number of visitors and the highest value of the natural potential of caves for the development of speleotourism and, similarly, a correlation between the lowest number of visitors and the lowest natural potential of caves for the development of speleotourism.

- 5.

- We assume that the Demänovská Cave of Liberty has the highest potential for speleotourism in terms of natural attractions and attendance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

- 1.

- We assumed the highest attendance of caves in 2019 is due to the continuously increasing number of tourists in Slovakia since 2014, culminating in 2019. This assumption has not been confirmed. Based on data from the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic [88], it follows that the number of participants in a personal travel per year has been steadily increasing since 2014, peaking in 2019, when the number of residents aged 15 and over who participated in tourism for personal purposes reached the number of 3,413,879. In total, 6,432,934 people took part in tourism in Slovakia in 2019, a 15% increase compared to 2018. The number of foreign tourists reached the value of 2,475,094 in 2019, which is a 9.7% increase compared to 2018. These indicators were not reflected in the total attendance of the studied caves. The peak of the number of visitors to the studied caves (Table 4) in the three summer months occurred in 2017 (426,251 visitors). The second highest value was 2016 (426,235), the third 2019 (426,199). However, the difference between the year 2016 and 2017 is almost negligible, only 16 visitors. If we take into account the year-round attendance of caves, according to the Slovak Caves Administration, there is also the highest value of attendance in 2017 (633,158 visitors), followed by 2019 (628,433) and 2018 (621,852). In 2020, due to the coronavirus pandemic, the total number of visitors to the 12 studied caves reached 384,834. However, the caves were open in that year only from June 16 to October 2. Overall, we can say that the number of visitors to the caves does not copy the number of tourists.

- 2.

- We expected the largest number of visitors in the Demänovská Cave of Liberty and the Belianska Cave, due to the high concentration of tourism participants in the Demänovská Valley in the Low Tatras National Park in winter and summer, as well as in the Tatra National Park in the case of the Belianska Cave. This assumption has been confirmed. The most visited cave in Slovakia is Belianska Cave. The total attendance in the cave for the three summer months in 2010–2019 reached 703,240 visitors. According to the Slovak Caves Administration, the year-round attendance for 2019 reached 144,376 and is also the highest of all caves. The second most visited is the Demänovská Cave of Liberty. The total attendance in the cave for the three summer months in 2010–2019 reached 647,830 visitors. According to the Slovak Caves Administration, the year-round attendance for 2019 reached 118,703 visitors and is also the second-highest of all caves. Both caves are located in national parks, which are among the most visited in Slovakia. Demänovská Dolina, in which the Demänovská Cave of Liberty lies, is the most important tourist center in the Low Tatras National Park, experiencing high attendance in summer and winter, as it is also the largest ski resort in Slovakia, Demänovská Dolina-Jasná. The cave is open all year round, except for the period from November 16 to January 1. This significant location factor is also confirmed by the second accessible cave of the Demänovská valley—the Demänovská Ice Cave, which is the third most visited cave during the summer months of the period 2010–2019. Belianska Cave is one of two accessible caves in the Tatra National Park (the other is the Brestovská Cave, which opened to the public in 2016). Attractive tourist destinations in summer and winter (several ski resorts) are situated nearby. The cave is increasingly visited even in bad weather and is also open all year round, except from November 16 to January 1.

- 3.

- We assumed that the guide’s approach and interpretation are essential factors in the cave’s overall evaluation regarding its attractiveness, respectively, the potential for speleotourism. This assumption was confirmed. It turns out that the guide’s approach, combined with the form of presentation and the content of the interpretation, is an essential factor in the overall perception of the cave’s attractiveness and, thus, its overall potential for speleotourism evaluation. Respondents especially appreciated the precise, detailed explanation of the cave being presented in a light, humorous form with the opportunity to ask additional questions. The Demänovská Cave of Liberty received the highest point rating within this classification index, but a relatively high point rating was also awarded to several other caves that were less attractive in terms of dimensions or variety of decoration. Deficiencies in the variety or attractiveness of decoration, or the dimension and spaciousness of the cave spaces, resulting from the cave’s very nature, can thus be compensated by the subjective factor of the guide’s approach and interpretation. This fact is more significantly reflected in the final evaluation of the potential, as the classification index interpretation of the guide belongs to the first class of three classification indices with the highest value of the index weight. The need for a variable and varied offer of classification indices (criteria, indicators) with different weights of significance is pointed out in the published works, e.g., [82,83,84,85] and others.

- 4.

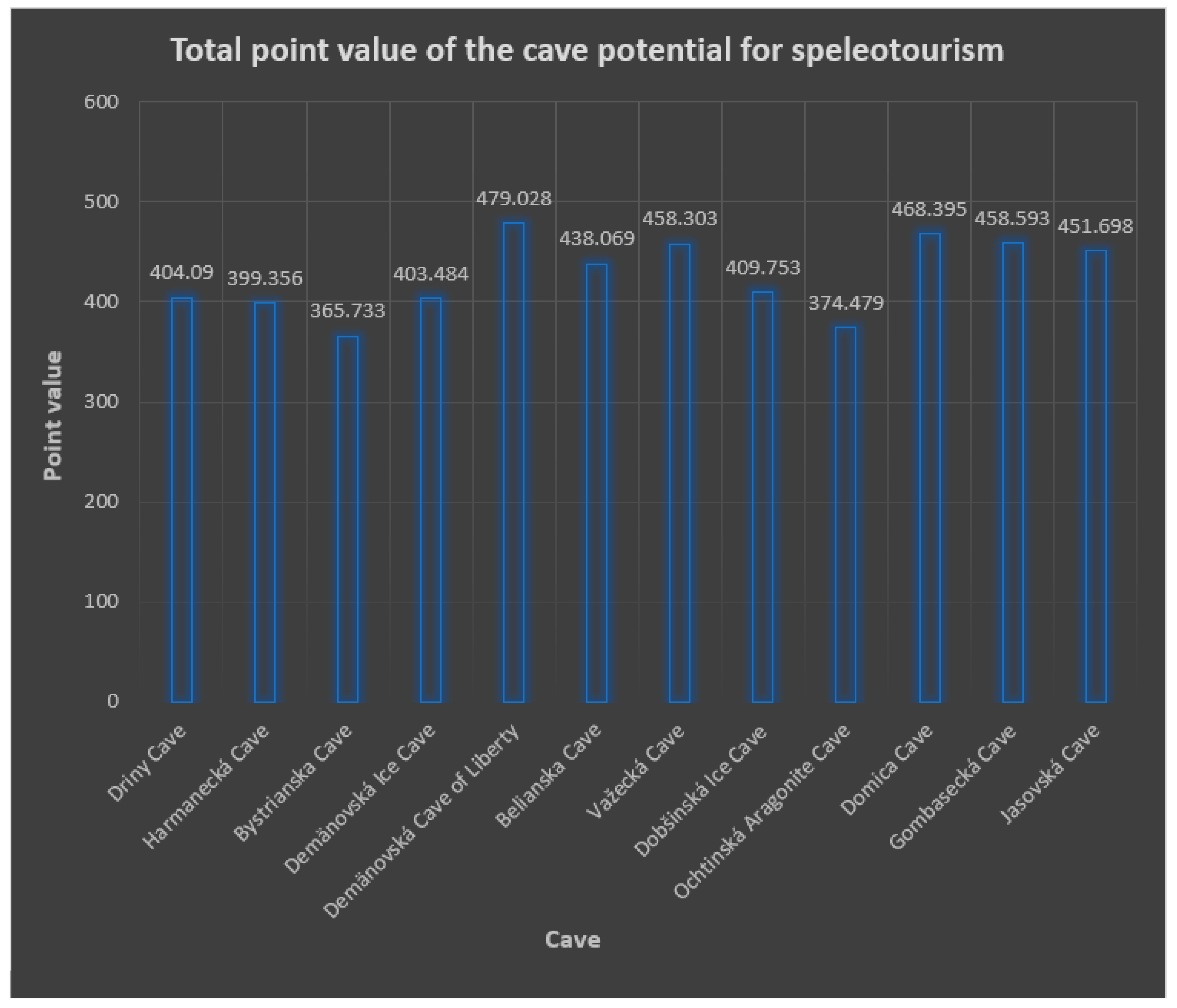

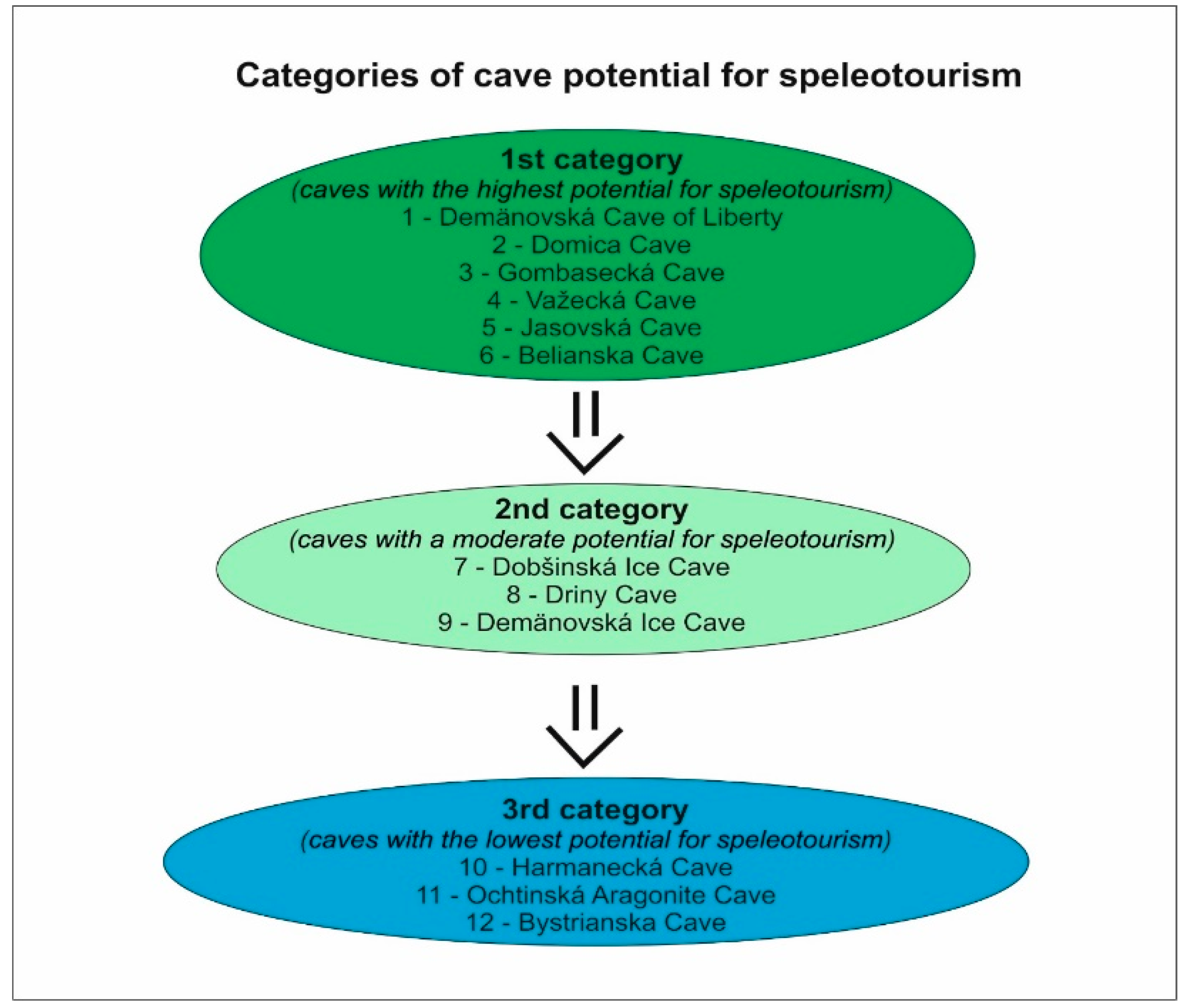

- We assumed a correlation between the highest number of visitors and the highest value of the cave potential for speleotourism; similarly, the correlation between the lowest number of visitors and the lowest potential of the cave for speleotourism. This assumption was not confirmed; respectively, it was confirmed only partially. Jasovská Cave, Važecká Cave, and Gombasecká Cave belong to the third category in terms of attendance (least visited caves), but in terms of evaluating the speleotourism potential, they belong to the first category (caves with the highest potential for speleotourism). Belianska Cave is the most visited cave (first category of attendance). Within the category of speleotourism potential, it is also a part of the first category (caves with the highest potential for speleotourism), but in the point evaluation, it ranks only in the sixth place in this category. Demänovská Cave of Liberty is the second most visited cave, and it ranks first in the potential for speleotourism category, so the assumption of correlation in its case was confirmed to a greater extent than in the case of the Belianská Cave. This relative correlation discrepancy between the rate of attendance and the potential of the cave for speleotourism also points to other factors that enter into evaluating the attractiveness and potential, respectively, which are decisive for tourists’ decision to visit the cave.

- 5.

- We assumed that the Demänovská Cave of Liberty would have the most significant potential for speleotourism. This assumption was proved. The cave is often mentioned in the media, in various promotional materials, and book guides for the domestic and foreign markets. It is located in one of the most visited valleys in Slovakia, where tourism is distributed evenly throughout the year. The character of the cave supports the point evaluation of the potential. The cave has a varied and lively decoration on the whole tour route, dominated by massive and large spaces, underground lakes, and a watercourse. In our opinion, only the Domica Cave in the Slovak Karst can compete with it, which was also confirmed by its second-highest value of potential. The Domica Cave has a similar character of spaces as the Demänovská Cave of Liberty with rich and varied decoration, huge spaces, underground lakes, and a watercourse. In addition to the Demänovská Cave of Liberty, the Domica Cave also has the option of boating on an underground watercourse, the occurrence of archaeological finds, including paintings, and the UNESCO World Natural Heritage brand is not negligible.

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- The correlation between attendance and the potential for speleotourism was not confirmed. The highest number of visitors does not mean the highest potential for speleotourism (for example, Belianska Cave).

- 2.

- A relatively similar amount of cave attendance in the years 2016–2019 is partly due to limitations, namely the ceiling of attendance at several caves.

- 3.

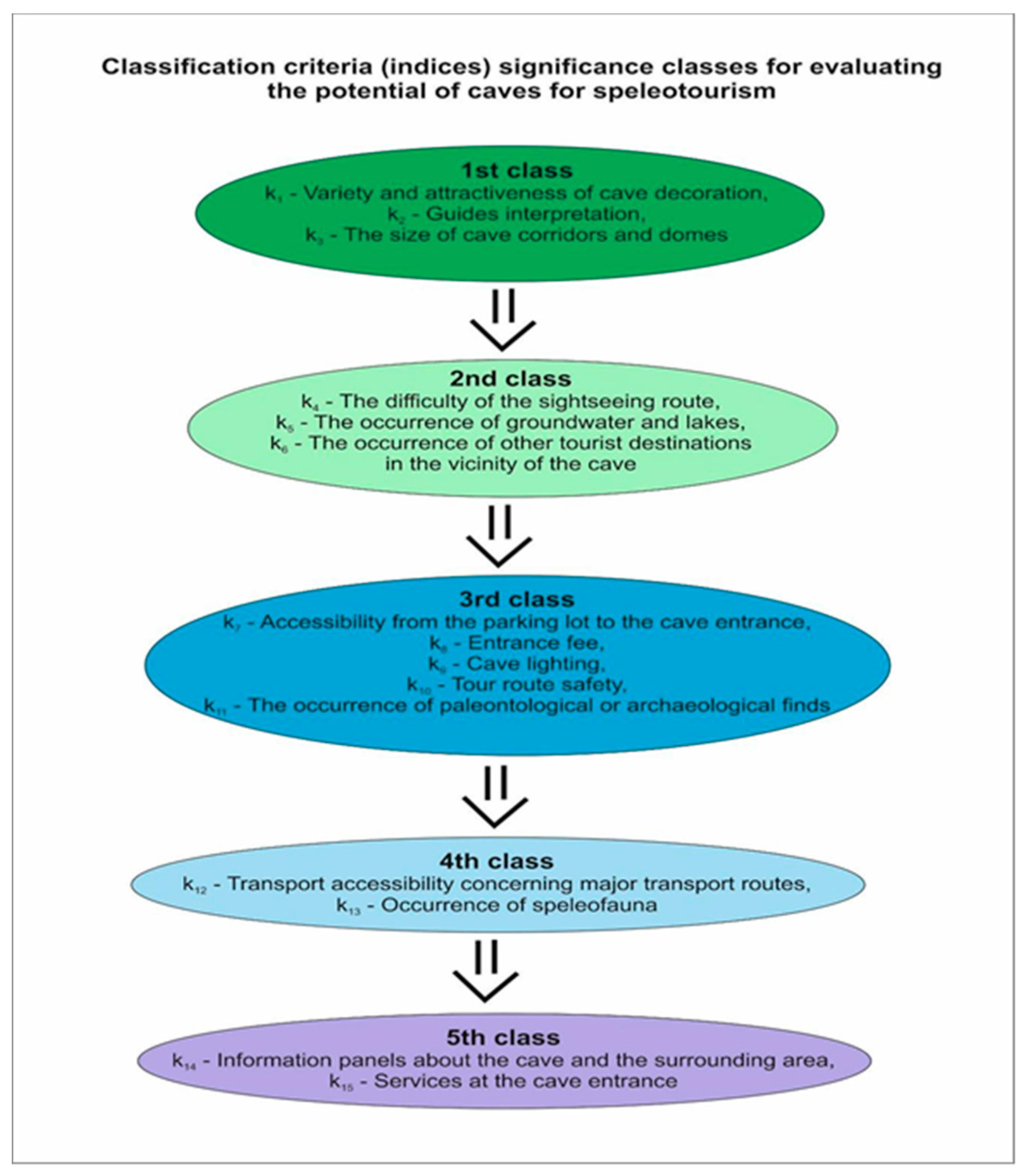

- Variety and attractiveness of cave decoration, guide interpretation, and the size of cave corridors and domes are among the most important criteria (they have the highest importance), on the basis of which the respondents evaluate the attractiveness and potential of caves for speleotourism.

- 4.

- In the case of 5 caves, the UNESCO World Natural Heritage brand does not automatically mean the highest attendance, with respect to the highest potential for speleotourism.

- 5.

- As expected, the Demänovská Cave of Freedom received the highest value of potential for speleotourism and also has the second highest attendance. The cave is well promoted, it is located in one of the most visited localities and the character of the cave itself helps the overall evaluation.

- 1.

- Pay attention to the strict selection of guides in the caves and their accompanying words, as the individual approach of the guide is considered by the respondents to be an important factor in the attractiveness and potential of the cave for speleotourism.

- 2.

- To regulate and monitor the impact of visitors in both ice caves, with regard to the decrease of ice decoration.

- 3.

- To ensure greater promotion of show caves in Slovakia at home and abroad, to bring them more into the public consciousness.

- 4.

- Implement the gradual renewal of the entrance areas of caves and sightseeing routes.

- 5.

- Review technical interventions in some caves, given the fragility and vulnerability of the cave geosystem, in order to make sustainable use of these areas.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lobo, H.A.S.; Trajano, E.; de Alcântara Marinho, M.; Bichuette, M.E.; Scaleante, J.A.B.; Scaleante, O.A.F.; Rocha, B.N.; Laterza, F.V. Projection of tourist scenarios onto fragility maps: Framework for determination of provisional tourist carrying capacity in a Brazilian show cave. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakál, J. Praktická Speleológia; Osveta: Martin, Slovakia, 1982; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Jakál, J. Krasová krajina, jej vlastnosti a odolnosť voči antropickým vplyvom. Geogr. Časopis 2002, 54, 381–392. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido-Bosch, A.; Martin-Rosales, W.; López-Chicano, M.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C.M.; Vallejos, A. Human impact in a tourist karstic cave (Aracena, Spain). Environ. Geol. 1997, 31, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fogaš, A. Jaskyne ako hlavné atraktivity cestovného ruchu v NP Slovenský kras a v Aggtelekskom národnom parku, Zmeny v štruktúre krajiny ako reflexia súčasných spoločenských zmien v strednej a východnej Európe. In Proceedings of the Zborník z III, Medzinárodného Geografického Kolokvia, Danišovce, Slovakia, 10–11 September 2005; Ústav geografie PF UPJŠ v Košiciach: Košice, Slovakia, 2005; pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cigna, A.A. Environmental management of tourist caves: The examples of Grotta di Castellana and Grotta Grande del Vento, Italy. Environ. Geol. 1993, 21, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Reyes, C.A.; Manco-Jaraba, D.C.; Castellanos-Alarcón, O.M. Geotourism in caves of Colombia as a novel strategy for the protection of natural and cultural heritage associated to underground ecosystems. Biodivers. Int. J. 2018, 2, 464–474. [Google Scholar]

- Gurnee, R.; Gurnee, J. The study report on the development of Harrison Cave, Barbados, West Indies. Atti Conv. Int. Grotte Tur. Borgio Verezzi 1981, 10, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cigna, A.A.; Burri, E. Development, management and economy of show caves. Int. J. Speleol. 2000, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, E.E.; Afoma, E.; Martha, I. Cave Tourism and its Implications to Tourism Development in Nigeria: A Case Study of Agu-Owuru Cave in Ezeagu. Int. J. Res. Tour. Hosp. (IJRTH) 2017, 3, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Aly, M.N.; Hamid, N.; Suharno, N.E.; Kholis, N.; Aroyandini, E.N. Community Involvement and Sustainable Cave Tourism Development in Tulungagung Region. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2021, 12, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, A.; Tomić, N.; Đordević, T.; Radulović, M.; Dević, I. Speleological objects becoming show caves: Evidence from the Valjevo karst area in Western Serbia. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artugyan, L. Geomorphosites assessment in karst terrains: Anina karst region (Banat Mountains, Romania). Geoheritage 2017, 9, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrat, A. Geology, geomorphology, geodiversity and geoconservation of the Sof Omar Cave System, Southeastern Ethiopia. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2015, 108, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, A. Tourism and show caves. Z. Für Geomorphol. Suppl. Issues 2016, 60, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, R.; Fletcher, L. The speleotourist experience: Approaches to show cave operations in Australia and China. Helictite 2016, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Garofano, M.; Govoni, D. Underground Geotourism: A Historic and Economic Overview of Show Caves and Show Mines in Italy. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, E.; Sumarmi, S.; Aliman, M. Participation of Green Environmental Group and Ulur-Ulur Local Wisdom on Buret Lake Ecotourism Management in Karst Area of Tulungagung, Indonesia. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2020, 30, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liso, I.; Chieco, M.; Fiore, A.; Pisano, L.; Parise, M. Underground Geosites and Caving Speleotourism: Some Considerations, From a Case Study in Southern Italy. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novas, N.; Gazquez, J.A.; Mac Lennan, J.; Garcia, R.M.; Fernandez-Ros, M.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. A real-time underground environment monitoring system for sustainable tourism of caves. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2707–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmiquel, L.; Alfonso, P.; Bascompta, M.; Vintró, C.; Parcerisa, D.; Oliva, J. Analysis of the European tourist mines and caves to design a monitoring system. Dyna 2018, 85, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavanddasht, M.; Karubi, M.; Sadry, B. An examination of the relationship between cave tourists’ motivations and satisfaction: The case of Alisadr Cave, Iran. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2017, 20, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Vukoičić, D.; Milosavljević, S.; Valjarević, A.; Nikolić, M.; Srećković-Batoćanin, D. The evaluation of geosites in the territory of National park Kopaonik (Serbia). Open Geosci. 2018, 10, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, A.A.; Forti, P. Caves: The most important geotouristic sigs in the world. Tour. Karst Areas 2013, 6, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, S.; Spate, A.; Hamilton-Smith, E. Visiting Show cave-Australia’s Oldest form of Geotourism. In Proceedings of the First Global Conference of Geotourism, Perth, Australia, 17–20 August 2008; pp. 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Antić, A.; Tomić, N. Geoheritage and geotourism potential of the Homolje area (eastern Serbia). Acta Geoturistica 2017, 8, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slomka, T.; Kicińska-Świderska, A. Geoturystyka–podstawowe pojecia. Geoturystyka 2004, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.K. Global Geotourism–An Emerging Form of Sustainable Tourism. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurek, W. Turystyka; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2007; p. 540. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonská, J.; Timčák, G.; Pixová, L. Geotourism and water quality of river Hornád (E. Slovakia). Acta Montan. Slovaca 2009, 14, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gerner, D.; Rybár, P.; Engel, J.; Domaracká, L. Geotourism marketing in Lake Constance’ region. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2009, 14, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Migoń, P. Geoturystyka; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A.; Vasiljević, D.A. Defining the Nature and Purpose of Modern Geotourism with Particular Reference to the United Kingdom and South-East Europe. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlovičová, K.; Klamár, R.; Mika, M. Turistika a Jej Formy; Grafotlač Prešov: Prešov, Slovakia, 2015; p. 550. ISBN 978-80-555-1530-4. [Google Scholar]

- Klamár, R.; Matlovič, R.; Mitura, T.; Buczek-Kowalik, M.; Kopor, I. Development of geotourism and mining heritage on the examples of Slovak opal mines and oil mine Bóbrka. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConference SGEM 2017, 17, 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R.K. (Eds.) Geotourism: The Tourism of Geology and Landscape; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2010; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Hronček, P.; Rybár, P. Relics of manual rock disintegration in historical underground spaces and their presentation in mining tourism. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2016, 21, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Różycki, P.; Dryglas, D. Mining tourism, sacral and other forms of tourism practiced in antique mines-analysis of the results. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2017, 22, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mingaleva, Z.; Zhulanov, E.; Shaidurova, N.; Molenda, M.; Gaponenko, A.; Šoltésová, M. The abandoned mines rehabilitation on the basis of speleotherapy: Used for sustainable development of the territory (the case study of the single industry town of mining industry). Acta Montan. Slovaca 2018, 23, 312–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Kim, M.; Park, J.; Guo, Y. Cave tourism: Tourists’ characteristics, motivations to visit, and the segmentation of their behaviours. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 13, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, A.; Tomić, N. Assessing the speleotourism potential together with archaeological and palaeontological heritage in Risovača cave (central Serbia). Acta Geoturistica 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Knežević, R.; Grbac-Žiković, R. Analysis of the condition and development opportunities of cave tourism in Primorsko-Goranska County. Turizam 2011, 15, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásková, M.; Zelenka, J. Výkladový Slovník Cestovního Ruchu; Ministerstvo Pro Místní Rozvoj: Praha, Czech Republic, 2002; p. 448. ISBN 80-239-0152-4. [Google Scholar]

- Panoš, V. Karsologická a Speleologická Terminologie; Knižné Centrum: Žilina, Czech Republic, 2001; p. 352. ISBN 80-8064-115-3. [Google Scholar]

- Antić, A. Speleotourism and tourist experience in Resava cave. Hotel. Tour. Manag. 2018, 6, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, H.A.; Moretti, E.C. Tourism in caves and the conservation of the speleological heritage: The case of Serrada Bodoquena (Mato Gross Do Sul State, Brazil). Acta Carsologica 2009, 38, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bocic, N.; Lukic, A.; Opacic, V.T. Management Models and Development of Show Caves as Tourist Destinations in Croatia. Acta Carsologica 2006, 35, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rachmawati, E.; Sunkar, A. Consumer-based cave travel and tourism market charakteristics in west Java, Indonesia. Tour. Karst Areas 2013, 6, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rindam, M. Cave Tourism: The Potentials of Ascar Cave as a Natural Tourism Asset at Lenggong Valley, Perak. SHS of Conferences Centre for Distance Education, University Sains Malaysia, 2014. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fc59/580839763f79255bf49a112961014b174e08.pdf?_ga=2.91786333.690534899.1584017531-1236247876.1580540673 (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Bella, P. Jaskyne; Prírodné krásy Slovenska. Dajama: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2011; p. 120. ISBN 978-80-8136-000. [Google Scholar]

- Čech, V.; Košová, V.; Pira, M. Brestovská Cave as a new locality for speleotourism in Slovakia. Acta Geoturistica 2019, 10, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bella, P.; Pavlarčík, S. Morfológia a problematika genézy Belianskej jaskyne. In Výskum, Využívanie a Ochrana Jaskýň; Zborník referátov (Stará Lesná), 3; Správa slovenských jaskýň: Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia, 2002; pp. 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Belanská Jaskyňa a Jej Kras; Vydavateľstvo Šport: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1959; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Bella, P. Fluviálna modelácia Bystrianskej jaskyne. In Výskum, Využívanie a Ochrana Jaskýň; Zborník referátov (Mlynky 1997), SSJ; Liptovský Mikuláš, Knižné Centrum: Žilina, Slovakia, 1998; pp. 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Speleologické problémy Bystrianskej jaskyne. Krásy Slovenska 1957, 34, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bella, P.; Haviarová, D.; Kováč, Ľ.; Lalkovič, M.; Sabol, M.; Soják, M.; Struhár, V.; Višňovská, Z.; Zelinka, J. Jaskyne Demänovskej Doliny; AEPress, s.r.o.: Bratislava (Vydala Štátna ochrana prírody SR), Slovakia, 2014; p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Demänovské Jaskyne. Krasové Zjavy Demänovskej Doliny; SAV: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1957; p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Demänovské Jaskyne a Zaujímavosti Krasu v Okolí; Šport: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1959; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Geomorfologické pomery Demänovskej Doliny. Slovenský Kras 1972, 10, 9–46. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Dobšinská ľadová jaskyňa. Geogr. Časopis 1957, 9, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Dobšinská Ľadová Jaskyňa; Šport: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1960; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Tulis, J.; Novotný, L. Dobšinská Ľadová Jaskyňa a Okolie. Geomorfologický a Speleologický Výskum; Záverečná správa. Mnscr., Správa Slovenských Jaskýň: Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia, 2002; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Bella, P. Geomorfologické pomery okolia jaskyne Domica. Aragonit 2001, 6, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Domica-Baradla Jaskyne Predhistorického Človeka; Šport: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1961; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Majko, J. Ako bola objavená jaskyňa Domica. Krásy Slovenska 1932, 11, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Smolenický kras v Malých Karpatoch. In Zemepisný Sborník SAV a Umení; 3, Slovenská Akadémia vied: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1951; pp. 7–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bella, P. Morfológia a genéza Gombaseckej jaskyne. Slovenský Kras 2003, 41, 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Gombasecká Jaskyňa; Šport: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1962; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Bella, P. Harmanecká jaskyňa-názory a problémy genézy, základné morfologické a genetické znaky. In Výskum, Využívanie a Ochrana Jaskýň; Zborník referátov (Demänovská Dolina 1999); Správa Slovenských jaskýň: Liptovský Mikuláš, Knižné Centrum, Žilina, Slovakia, 2000; pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Himmel, J. Jeskyně a vyvěračky východní části Jasovské planiny v Jihoslovenském krasu. Kras Československu 1963, 1–2, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Vzťah horizontálnych chodieb Jasovskej jaskyne k terasám Bodvy. In Problémy Geografického Výskumu; zborník referátov z X. zjazdu čs. geografov v Prešove (1965); Katedra geografie UPJŠ: Prešov, Slovakia, 1971; pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Erdos, M. Dokumentácia a Registrácia Povrchových a Podzemných Krasových Foriem Slovenského Krasu-Jasovská Planina, Manuskript; Múzeum Slovenského Krasu: Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia, 1975; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Bella, P. Geomorfologické pomery Ochtinskej aragonitovej jaskyne. Slovenský Kras 2004, 42, 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Ochtinská aragonitová jaskyňa. Geogr. Časopis 1957, 9, 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Gaál, Ľ. Krasové javy v okolí Hrádku a ich vzťah k Ochtinskej aragonitovej jaskyni. In Výskum, Využívanie a Ochrana Jaskýň; Zborník referátov (Mlynky 1997); Správa Slovenských jaskýň: Liptovský Mikuláš, Knižné Centrum, Žilina, Slovakia, 1998; pp. 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gaál, Ľ. Geológia Ochtinskej aragonitovej jaskyne. Slovenský Kras 2004, 42, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Homza, Š.; Rajman, L.; Roda, Š. Vznik a vývoj krasového fenoménu Ochtinskej aragonitovej jaskyne. Slovenský Kras 1970, 8, 21–68. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Važecká Jaskyňa a Krasové Javy v Okolí; Šport: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1962; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Droppa, A. Speleologický výskum Važeckého krasu. Geogr. Časopis 1962, 14, 264–293. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Powell, E. Questionnaire Design: Asking Questions with a Purpose; University of Wisconsin Extension: Madison, WI, USA, 1998; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Švec, Š. Metodológia vied o výchove: Kvantitatívno-Scientické a Kvalitatívno-Humanitné Prístupy v Edukačnom Výskume; Iris: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tičar, J.; Tomić, N.; Valjavec, M.B.; Zorn, M.; Marković, S.B.; Gavrilov, M.B. Speleotourism in Slovenia: Balancing between mass tourism and geoheritage protection. Open Geosci. 2018, 10, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, N.; Božić, S. A modified Geosite Assessment Model (M-GAM) and its Application on the Lazar Canyon area (Serbia). Int. J. Environ. Res. 2014, 8, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Tomić, N.; Antić, A.; Marković, S.B.; Dordević, T.; Zorn, M.; Valjavec, M.B. Exploring the Potential for Speleotourism Development in Eastern Serbia. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujičić, M.D.; Vasiljević, D.A.; Markovič, S.B.; Hose, T.A.; Lukić, T.; Hadžić, O.; Janićević, S. Preliminary geosite asessment model (gam) and its application on Fruška gora mountain, potential geotourism destination of Serbia. Acta Geogr. Slovenica 2011, 51–52, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Říha, J. Hodnocení vlivu investic na životní prostředí. In Vícekriteriální Analýza a EIA. Evaluation of the Impact of Investments on the Environment. Multicriteria Analysis and EIA; Nakladatelství ACADEMIA: Praha, Czech Republic, 1995; p. 348. [Google Scholar]

- Říha, J. Objektivizace vah kritérií v procesu EIA. Objectification of criteria weights in the EIA process. Stavební Obz. 1995, 1, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Özoğlu, M. Basic Indicators of Holiday and Business Trips in 2019; Štatistický úrad Slovenskej Republiky: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2020; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

| Entrance Elevation (m a.s.l.) | Ascent to the Cave from the Parking Lot (min) | Overall Cave Length (m) | Length of the Tour (m) | Elevation Difference of the Tour (m) | Number of Stairs on the Tour | Time Needed to Complete the Tour (min) | Ticket Price for Adult Person in € (2020) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belianska Cave | 890 | 25 | 3829 | 1370 | 125 | 874 | 70 | 9 |

| Bystrianska Cave | 565 | 1 | 3531 | 580 | 0 | 26 | 45 | 6 |

| Demänovská Cave of Liberty | 870 | 15 | 11,117 | 1150 (traditional tour) 2150 (long tour) | 86 (both tours) | 913 (t.t.) 1 118 (l.t.) | 60 (traditional tour) 100 (long tour) | 9 (traditional tour) 16 (long tour) |

| Demänovská Ice Cave | 840 | 20 | 2445 | 650 | 48 | 670 | 45 | 8 |

| Dobšinská Ice Cave | 969.5 | 25 | 1491 | 515 | 43 | 500 | 30 | 8 |

| Domica Cave | 339 | 1 | 5368 | 780 (short tour) 930 (tour with a boat ride) | 7 | ? | 45 (short tour) 60 (tour with a boat ride) | 6 (short tour) 8 (tour with a boat ride) |

| Driny Cave | 399 | 20 | 680 | 450 | 10 | 151 | 35 | 6 |

| Gombasecká Cave | 250 | 2 | 1525 | 530 | 8 | 87 | 30 | 6 |

| Harmanecká Cave | 821 | 40 | 3123 | 1020 | 64 | 1042 | 60 | 7 |

| Jasovská Cave | 257 | 1 | 2811 | 720 | 30 | 339 | 45 | 6 |

| Ochtinská Aragonite Cave | 642 | 10 | 585 | 300 | 19 | 104 | 30 | 7 |

| Važecká Cave | 784 | 1 | 530 | 235 | 5 | 88 | 25 | 5 |

| Classification Index (Criterion) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variety and attractiveness of cave decoration | 1 | 2 | 14.5 | 0.104 |

| Guide interpretation | 1 | 2 | 14.5 | 0.104 |

| The size of cave corridors and domes | 1 | 2 | 14.5 | 0.104 |

| The difficulty of the sightseeing route | 2 | 5 | 12.5 | 0.089 |

| The occurrence of groundwater and lakes | 2 | 5 | 12.5 | 0.089 |

| The occurrence of other tourist destinations in the vicinity of the cave | 2 | 5 | 12.5 | 0.089 |

| Accessibility from the parking lot to the cave entrance | 3 | 9 | 9 | 0.064 |

| Entrance fee | 3 | 9 | 9 | 0.064 |

| Cave lighting | 3 | 9 | 9 | 0.064 |

| Tour route safety | 3 | 9 | 9 | 0.064 |

| The occurrence of paleontological or archaeological finds | 3 | 9 | 9 | 0.064 |

| Transport accessibility concerning major transport routes | 4 | 12.5 | 5 | 0.036 |

| Occurrence of speleofauna | 4 | 12.5 | 5 | 0.036 |

| Information panels about the cave and the surrounding area | 5 | 14.5 | 2 | 0.014 |

| Services at the cave entrance | 5 | 14.5 | 2 | 0.014 |

| Rich occurrence of dripstone (or ice) decoration along the entire tour route | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.312 |

| Sporadic occurrence of dripstone (or ice) decoration in some corridors and halls | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.208 |

| Low occurrence of decoration, a predominance of spaces without dripstone (or ice) decoration | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0.104 |

| Cave | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belianska Cave | 55,496 | 63,120 | 60,402 | 64,801 | 69,056 | 64,662 | 77,086 | 76,902 | 84,171 | 87,544 |

| Bystrianska Cave | 12,298 | 12,597 | 12,994 | 12,180 | 13,942 | 14,632 | 15,281 | 16,842 | 17,982 | 17,821 |

| Demänovská Cave of Liberty | 58,195 | 63,118 | 59,845 | 61,403 | 61,692 | 62,337 | 76,090 | 69,174 | 67,074 | 68,902 |

| Demänovská Ice Cave | 56,367 | 37,267 | 60,085 | 62,889 | 62,161 | 62,468 | 66,250 | 66,710 | 64,241 | 62,072 |

| Dobšinská Ice Cave | 45,120 | 48,606 | 49,438 | 48,890 | 52,581 | 57,868 | 67,024 | 72,174 | 68,384 | 68,681 |

| Domica Cave | 17,554 | 18,537 | 11,614 | 16,371 | 13,298 | 13,646 | 27,835 | 19,583 | 19,111 | 16,083 |

| Driny Cave | 21,323 | 21,461 | 24,880 | 24,795 | 23,946 | 24,744 | 27,518 | 28,277 | 26,730 | 26,256 |

| Gombasecká Cave | 5863 | 6056 | 6125 | 5057 | 6153 | 6609 | 8283 | 9505 | 8645 | 10,629 |

| Harmanecká Cave | 11,076 | 14,342 | 14,976 | 13,988 | 13,880 | 15,846 | 16,345 | 15,857 | 15,148 | 16,166 |

| Jasovská Cave | 7712 | 9947 | 10,491 | 11,022 | 11,684 | 12,496 | 11,683 | 14,532 | 12,719 | 14,773 |

| Ochtinská Aragonite Cave | 16,407 | 17,127 | 16,165 | 14,319 | 17,112 | 18,925 | 20,575 | 24,193 | 22,110 | 25,253 |

| Važecká Cave | 10,270 | 10,678 | 9859 | 9893 | 11,080 | 11,183 | 12,265 | 12,502 | 13,172 | 12,019 |

| SUM | 317,681 | 322,856 | 336,874 | 345,608 | 356,585 | 365,416 | 426,235 | 426,251 | 419,487 | 426,199 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1 | 41.392 | 55.536 | 34.424 | 28.912 | 62.192 | 59.952 | 49.504 | 53.04 | 55.224 | 55.774 | 52.832 | 51.168 |

| k2 | 41.6 | 48.092 | 39.104 | 40.856 | 63.056 | 44.096 | 39.088 | 48.192 | 45.36 | 29.224 | 46.488 | 44.512 |

| k3 | 23.608 | 54.184 | 29.432 | 56.472 | 56.68 | 56.368 | 49.816 | 52.728 | 25.168 | 50.336 | 36.816 | 43.888 |

| k4 | 42.364 | 27.234 | 48.597 | 28.569 | 24.202 | 27.926 | 48.683 | 43.254 | 46.636 | 36.579 | 48.772 | 40.139 |

| k5 | 32.841 | 35.6 | 18.067 | 21.538 | 51.4 | 45.6 | 34.71 | 18.423 | 17.8 | 53.4 | 48.861 | 34.532 |

| k6 | 46.013 | 32.93 | 22.695 | 48.06 | 49.662 | 42.129 | 30.438 | 49.128 | 24.119 | 37.558 | 38.537 | 39.882 |

| k7 | 23.616 | 14.592 | 38.272 | 18.504 | 21.952 | 24.192 | 38.4 | 21.632 | 26.496 | 38.4 | 38.08 | 37.12 |

| k8 | 23.68 | 22.144 | 18.88 | 16.704 | 20.992 | 23.552 | 21.824 | 20.736 | 20.416 | 20.928 | 23.68 | 22.976 |

| k9 | 34.368 | 29.44 | 32.152 | 33.91 | 34.624 | 33.984 | 34.048 | 25.312 | 35.2 | 31.744 | 35.328 | 32.386 |

| k10 | 33.792 | 31.616 | 34.608 | 27.264 | 33.664 | 28.928 | 35.136 | 29.504 | 34.752 | 32.256 | 35.52 | 30.976 |

| k11 | 13.248 | 13.504 | 15.808 | 35.776 | 13.312 | 12.8 | 36.544 | 13.888 | 12.8 | 36.928 | 13.824 | 30.464 |

| k12 | 19.512 | 11.484 | 14.328 | 19.8 | 19.44 | 15.012 | 19.08 | 10.476 | 9.792 | 13.752 | 15.792 | 16.036 |

| k13 | 14.112 | 11.376 | 8.712 | 15.127 | 12.452 | 8.676 | 10.247 | 9.795 | 7.043 | 16.071 | 12.475 | 13.276 |

| k14 | 7.672 | 7.48 | 4.018 | 8.271 | 7.798 | 7.63 | 6.027 | 7.617 | 7.128 | 8.417 | 6.417 | 7.512 |

| k15 | 6.272 | 4.144 | 6.636 | 3.721 | 7.602 | 7.224 | 4.758 | 6.028 | 6.545 | 7.028 | 5.171 | 6.831 |

| K | 404.09 | 399.356 | 365.733 | 403.484 | 479.028 | 438.069 | 458.303 | 409.753 | 374.479 | 468.395 | 458.593 | 451.698 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čech, V.; Chrastina, P.; Gregorová, B.; Hronček, P.; Klamár, R.; Košová, V. Analysis of Attendance and Speleotourism Potential of Accessible Caves in Karst Landscape of Slovakia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115881

Čech V, Chrastina P, Gregorová B, Hronček P, Klamár R, Košová V. Analysis of Attendance and Speleotourism Potential of Accessible Caves in Karst Landscape of Slovakia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):5881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115881

Chicago/Turabian StyleČech, Vladimír, Peter Chrastina, Bohuslava Gregorová, Pavel Hronček, Radoslav Klamár, and Vladislava Košová. 2021. "Analysis of Attendance and Speleotourism Potential of Accessible Caves in Karst Landscape of Slovakia" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 5881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115881

APA StyleČech, V., Chrastina, P., Gregorová, B., Hronček, P., Klamár, R., & Košová, V. (2021). Analysis of Attendance and Speleotourism Potential of Accessible Caves in Karst Landscape of Slovakia. Sustainability, 13(11), 5881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115881