Evolution of the Concept of Sensory Gardens in the Generally Accessible Space of a Large City: Analysis of Multiple Cases from Kraków (Poland) Using the Therapeutic Space Attribute Rating Method

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Evolution of the Idea of Sensory Gardens in Poland

3. Object of Study

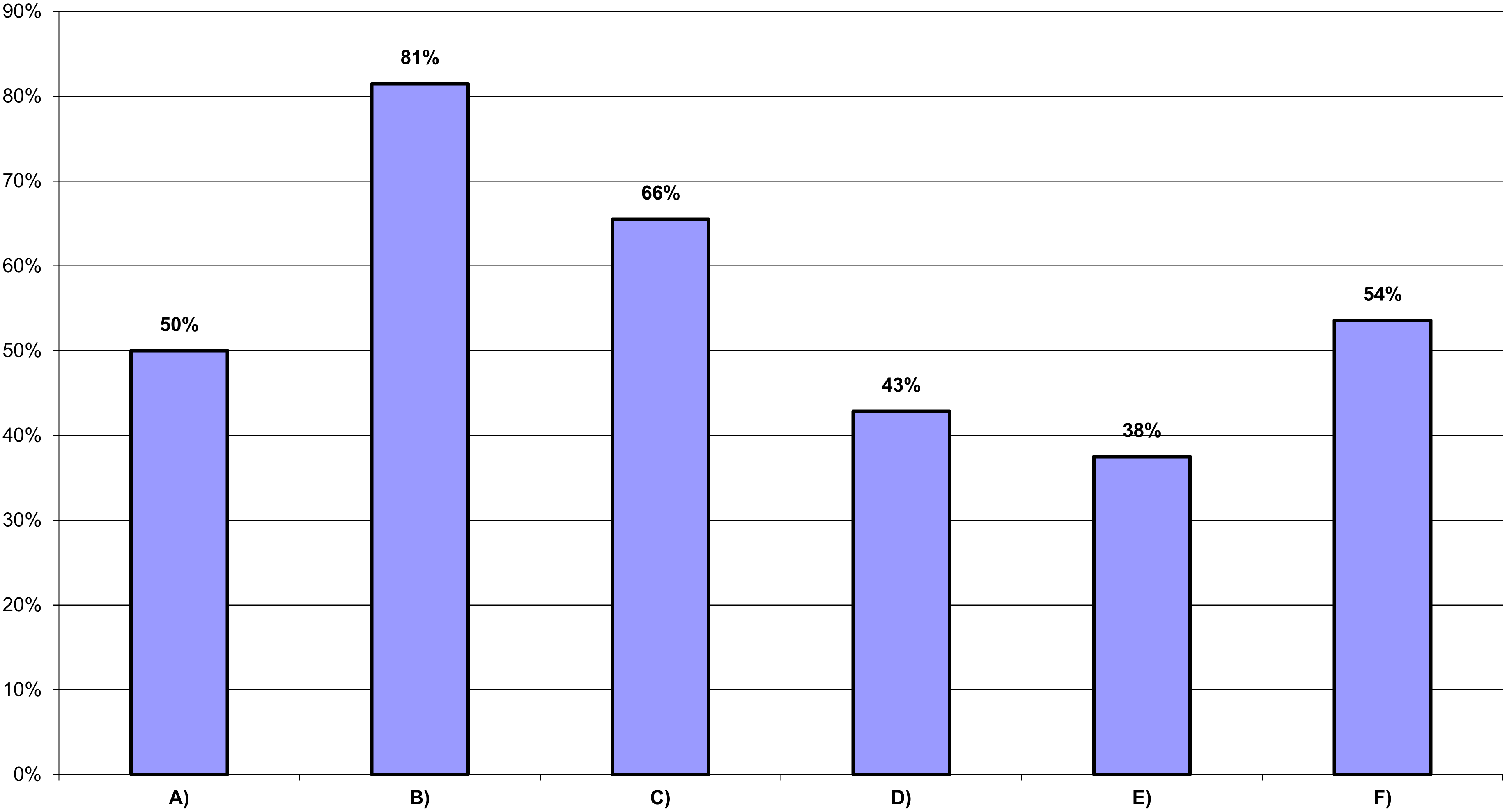

- (A)

- ‘Zapachowo’—fragrance garden in the S. Lem Educational Park (2013)—ca. 742 m2;

- (B)

- Sensory Garden at the Piaski Nowe housing estate (2019)—ca. 903 m2 (Figure 2);

- (C)

- Garden with sensory features near the J. Czapski Musuem (2018–2019)—ca. 260 m2 (Figure 3);

- (D)

- Sensory garden with a sensory path in Tysiąclecia Park (2020)—ca. 1840 m2;

- (E)

- Sensory garden in Reduta Park (2020)—ca. 2385 m2;

- (F)

- Playground with sensory features in Jordan Park (built gradually, mostly in recent years)—ca. 2800 m2.

4. Research Method

- they should be designed with the intent to stimulate human senses;

- they should form a complete whole, isolated from the surroundings;

- they should affect all the senses;

- they should focus on non-visual stimulation;

- apart from sense-stimulating plants, they should also feature other elements that stimulate the senses.

- they should be animal-friendly, as the presence of animals increases the scope of positive stimuli [17];

- they should be equipped with water features, because of their sonic properties and their importance for plants and animals;

- they should have dedicated use indications that facilitate experiencing the garden from up close [17];

5. Results

5.1. Location of Kraków’s Gardens with Sensory Features and Their Users

5.2. Sensory Stimulation in Kraków’s Sensory Gardens

5.3. Garden Attribute Analysis

- 1—the attribute was present, and its potential was being used well,

- 0.5—the attribute was present, but it was not used to its full potential,

- 0—the attribute was not present.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Winterbottom, D.; Wagenfeld, A. Therapeutic Gardens: Design for Healing Spaces; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Health Benefits for Gardens in Hospitals. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A & M University, College State, TX, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, H. Using the sensory garden as a tool to enhance the educational development and social interaction of children with special needs. Support Learn. 2010, 25, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.T.; Kirkevold, M. Clinical use of sensory gardens and outdoor environment in Norvegian nursing homes: A cross-sectional e-mail survey. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 36, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balode, L. The design guidelines for therapeutic sensory gardens. Res. Rural Dev. 2013, 2, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sensory Trust. Available online: Sensorytrust.org.uk/information/factsheets/sensory-garden-1.html (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Hussein, H. Sensory Garden in Special Schools: The issues, design and use. J. Des. Built Environ. 2009, 5, 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pawłowska, K. Ogród sensoryczny. In Dźwięk w Krajobrazie Jako Przedmiot Badań Interdyscyplinarnych. Prace Komisji Krajobrazu Kulturowego PTG; Bernat, S., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Polihymnia: Lublin, Poland, 2008; Volume XI, pp. 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Dudkiewicz, M.; Marcinek, B.; Tkaczyk, A. Idea ogrodu sensorycznego w koncepcji zagospodarowania atrium przy Szpitalu Klinicznym nr 4 w Lublinie. Acta Sci. Pol. Archit. 2014, 13, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Górska-Kłęk, L. ABC Zielonej Opieki. Seria „Biblioteka Nestora”, t. VIII; Dolnośląski Ośrodek Polityki Społecznej: Wrocław, Poland, 2016; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowska, M. Parki i Ogrody Terapeutyczne; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN SA: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbski, M.; Dudkiewicz, M. Przystosowanie ogrodu dla niewidomego użytkownika na przykładzie ogrodów sensorycznych w Bolestraszycach, Bucharzewie i Powsinie. Teka Kom. Archit. Urban. Studiów Kraj. 2010, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowska, M. Sensory gardens inclusively designed for visually impaired users. PhD Interdiscip. J. 2014, 1, 30–317. [Google Scholar]

- Woźny, A.; Lauda, A. Ogrody dla osób z dysfunkcją wzroku w świetle ich oczekiwań. Archit. Kraj. 2014, 4, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zajadacz, A.; Lubarska, A. Sensory gardens as places for outdoor recreation adapted to the needs of people with visual impairments. Studia Perieget. 2020, 2, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, J.M. Hype, Hyperbole, and Health: Therapeutic site design. In Urban Lifestyles: Spaces, Places People; Benson, J.F., Rowe, M.H., Eds.; Brookfield A. A. Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz, I.; Moszkowicz, Ł.; Porada, K. Znaczenie miejskich ogrodów sensorycznych o cechach przyjaznych organizmom rodzimym, na przykładzie dwóch przypadków z terenu dużych miast europejskich: Krakowa i Londynu. In Integracja Sztuki i Techniki w Architekturze i Urbanistyce; Wydawnictwa Uczelniane Uniwersytetu Technologiczno-Przyrodniczego: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2020; pp. 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczko, D. Ogrody sensoryczne na Błoniach Niepołomickich; Cracow University of Technology: Kraków, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kraków w Liczbach. 2019, Urząd Miasta Krakowa. Available online: https://www.bip.krakow.pl/?mmi=6353 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Kondracki, J. Geografia Regionalna Polski; Polskie Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warszawa, Poland, 2001; p. 441. [Google Scholar]

- Rackiewicz, I. Diagnoza Stanu Środowiska Miasta Krakowa; Urząd Miasta Krakowa: Kraków, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowska, M. The Universal Pattern of Design for Therapeutic Parks. Methods of Use. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2018, 9, 1410–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, A.; Grahn, P. Outdoor environments in healthcare settings: A quality evaluation tool for use in designing healthcare gardens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 13, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowacki, J.; Bunalski, M.; Sienkiewicz, P. Fauna jako istotny element hortiterapii. In Hortiterapia Jako Element Wspomagający Leczenie Tradycyjne; Krzymińska, A., Ed.; Rhytmos: Poznań, Poland, 2012; pp. 117–144. [Google Scholar]

- Moszkowicz, Ł.; Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz, I. Impact of the public parks location in the city on the richness and diversity of herbaceous vascular plants on the example of Krakow Southern Poland. In Proceedings of the Plants in Urban Areas and Landscape, Nitra, Slovakia, 7–8 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmer, P. Pollination and Floral Ecology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2011; p. 778. [Google Scholar]

- Chance, H.; Winterbottom, D.; Bell, J.; Wagenfeld, A. Gardens for Well-Being in Workplace Environments. In Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference on Design4Health, Sheffield, UK, 13–16 July 2015; Available online: https://research.shu.ac.uk/design4health/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/D4H_Chance_et_al.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Chang, C.Y.; Chen, P.K. Human Response to window views and indoor plants in the workplace. HortScience 2005, 40, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Garden with Sensory Features | General Overview | Location Overview | Use, Users | Urban Activity Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) in the Educational S. Lem Park | The garden has a freeform composition and consists of a path that meanders between fragrant plants | The garden is a part of a sensory educational park that familiarises users with the laws of physics and that features several dozen installations for personal experimentation | Learning through play, primarily for children, the youth, and adults | Educational zone |

| (B) accompanying the J. Czapski Museum | The garden has a geometric layout and consists of a large, square lawn and a path that runs around it and leads to the museum building. There are tall pots, mostly with fragrant plants and herbs, along the path | The garden is located in the city centre and belongs to the J. Czapski Museum grounds It was designed as a place intended for the museum’s supplementary events. The building’s outer wall is used as a screen for film screenings, and there is also a coffee shop in the garden. There is another Museum nearby, named after E. Hutten-Czapski | Cultural activity intended for visitors to the city and its residents | Cultural and tourist zone |

| (C) at the Nowe Piaski housing estate | It was designed with central paths extending from a central section and leading to various garden interiors. It has a wealth of plants and small meadows covered with grass and surrounded by greenery | The garden is located on a typical block housing estate distinctive for large Polish cities. The garden is surrounded by housing blocks, streets, and parking lots | Local communal activity, it is also used as a meeting space and to stimulate activity among seniors | Urban housing estate resident activity zone |

| (D) in Tysiąclecia Park | The garden consists of several sections, its composition is part-freeform and part-geometric. | The garden is located in the centre of a large city park | Outdoor exercise and rest among greenery for local citizens | Recreational zone in an urban green area |

| (E) in Reduta Park | The garden is located on a slope; most of it is geometric. It features large, narrow beds with fruit bushes and low beds mostly filled with fragrant herbs. The garden features a coffee shop with a roof with a gravel surface and low planters with fragrant plants. The roof can be reached via stairs. | The garden is located in a large city park | Outdoor exercise and rest among greenery for local citizens | Recreational zone in an urban green area |

| (F) in H. Jordan Park | The garden was built gradually and consists of a sand garden, a section of wooden play equipment for children, a fountain with jets in the pavement surface, and a green labyrinth. | The garden is located in a large park which has been dedicated to children’s and youth activity from its inception. | Stimulating children and the youth to lead an active and healthy lifestyle | A zone dedicated to sports activity among children and the youth |

| Garden with Sensory Features | Taste | Touch | Sight | Hearing | Smell | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) in the Educational S. Lem Park | None | There is a sensory path near the garden—tactile sensations in feet | Flowers, greenery, plants | People laughing, birds singing | Large areas of fragrant herbs | There is a plant-based labyrinth near the garden |

| (B) accompanying the J. Czapski Museum | Fruits | The touch of grass, plants, sensory path—tactile sensations in feet | Colours of flowers, fruits, narrow mirrors that reflect plants | Insect buzzing | Fragrant herbs and flowers | Wigwam from willow branches, isolated meadows with grass, a small sensory path |

| (C) at the Nowe Piaski housing estate | The taste of herbs, nearby coffee shop | Ability to touch plants with different textures | Green and white—the plants and the surroundings | Insect buzzing | Fragrant herbs and flowers | None |

| (D) in Tysiąclecia Park | None | The touch of perennial plants, sensory path—tactile sensations in feet | Colours of flowers | The sound of water (a fountain) | Bitterling, the smell of herbs and flowers | Elements in the form of a line net |

| (E) in Reduta Park | Fruits | None | Colours of flowers | Insect buzzing | Smell of herbs | Observation deck with gravel surface |

| (F) in H. Jordan Park | None | Touch of sand, water, and wood | Green of plants, clear water | Sound of steps on wooden surfaces, birds singing, the sound of water | None | Labyrinth made of plants |

| The First Group of Attributes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (D) | (E) | (F) | ||

| Functional Programme | Attribute | ||||||

| (a) Enabling physical and psychological regeneration | Places for rest that facilitate experiencing the surroundings from up close | YES/NO (0.5) too few benches, but they are deep in the garden | YES (1) many seats in various parts of the garden, there is also a small meadow with sunbeds | YES/NO (0.5) there are seats on a platform, but no isolated places or places near plants | YES/NO (0.5) there are seats in various places, but usually along the main path | YES/NO (0.5) too few benches, only in selected places and arranged linearly | YES/NO (0.5) too few benches |

| Isolation from the urban environment, noise, smells, and the pressure of time and fast living | YES (1) the garden is at the edge of a science garden and faces the park | YES (1) densely placed plants partially insulate from streets, but there are also places deeper in the garden | YES (1) the garden is located in an interior courtyard | NO (0) a busy path runs through the garden, no plants along the edges | YES/NO (0.5) frequented paths run through the garden, and there is a playground nearby, but the park itself is isolated from busy streets | YES/NO (0.5) the garden is near the park’s outer fence, but there are bushes and trees here | |

| Ability to easily observe animals or people | YES/NO (0.5) insects—there are taller bushes, but many plants are close to the soil surface | YES (1) insects and birds—there are both taller bushes and perennials, as well as bench-side plants | YES (1) insects, as plants are in taller pots | YES/NO (0.5) there are taller perennials, but most plants are short | NO (0)—the benches are placed in a way that prevents a comfortable observation of the nearby park area | YES (1) ability to observe children at play, or birds | |

| (b) Facilitating social contact | Ability to meet as a group | YES/NO (0.5) there is a small space with three benches, but the main path crosses through it, which can make conversing difficult | YES (1) there is a meeting space; benches are often placed in pairs and at an angle, facilitating eye contact and conversation | YES (1) there is a space for meetings—a terrace with chairs and tables that can be rearranged | YES/NO (0.5) meetings are possible, but usually for two people—benches and chairs are placed in pairs | YES/NO (0.5) ability to meet at a coffee shop, but the sensory spaces do not facilitate this | YES (1) the entire space allows group play |

| (c) Facilitating physical activity | Places for play and recreation | YES (1) a large lawn, with equipment for performing experiments nearby | YES (1) a meadow in a garden with sunbeds and a wigwam made of living willow branches for children | YES/NO (0.5) there is a lawn, but due to the proximity of a Museum it is not used for physical activity | YES (1) features with a line net suspended from metal frames; extensive lawns nearby | YES/NO (0.5) there are lawns, but the site is on a slope, which excludes several activity types | YES (1) the entire area facilitates play for children and their caretakers |

| Place dedicated to gardening classes or hortitherapy | NO (0)—absent | YES (1) a large table for classes in the central part | NO (0)—absent | NO (0)—absent | NO (0)—absent | NO (0)—absent | |

| (d) Meeting essential user needs | Safety in the garden space | YES (1) the garden is located in a larger, fenced science garden | YES (1) the garden is fenced | YES (1) the garden is close to the Museum, in its internal courtyard | NO (0) lack of isolation from the remainder of the park | NO (0) lack of isolation from the remainder of the park | YES (1) the site is fenced with a low fence |

| Safety in direct contact with plants | YES (0.5) the plants are safe, but there are also roses | YES/NO (0.5) most plants are safe, but there are also prickly plants | YES (1) safe plants were used, mainly herbs | YES/NO (0.5) there are rose bushes around a fountain | YES/NO (0.5) safe plants were used, but there are gooseberry bushes | YES (1) the labyrinth is made from safe plants | |

| Seating or shelter | YES/NO (0.5) there is shelter under tree canopies | YES (1) shelter under a sail suspended above the garden’s central space | YES (1) shelter inside a coffee shop that opens towards the garden | YES (0.5) there is shelter under tree canopies | YES (1) shelter inside a coffee shop | YES/NO (0.5) there is shelter under tree canopies | |

| Sunny and shaded places | YES/NO (0.5) there are only sunny spaces in the garden | YES (1) | YES (1) | YES (1) | YES/NO (0.5) there are only sunny spaces in the garden | YES (1) | |

| Amenities for the disabled | NO (0) a gravel path with solid strips, but turns are at an angle that make it impossible for wheelchair-bound persons to make them | YES/NO (0.5) wide paths, but no amenities for the blind | YES/NO (0.5) wide paths, but no dedicated amenities for the blind | YES/NO (0.5) wide, even paths, but no dedicated amenities for the blind | NO (0) the garden is on a slope, the paths along bushes are narrow and dead-ended, which hinders wheelchair movement, stairs to the observation deck | NO (0) absent | |

| Elements that indirectly affect comfort of use: access to food and drink, toilets, and others | YES (1) they are present in the park | YES/NO (0.5) they are absent in the park; there are bicycle stands and waste bins | YES (1) there is a coffee shop that opens towards the garden | YES/NO (0.5) there are bicycle stands | YES (1) there is a coffee shop with restrooms | YES (1) they are present in the park | |

| (e) Cognitive support | Features that facilitate education in the garden | YES (1) plaques with plant names | YES (1) information boards that also feature plant names | NO (0) | NO (0) no plaques | NO (0) no plaques | YES/NO (0.5) learning through play facilitated by playground equipment |

| The Second Group of Attributes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (D) | (E) | (F) | ||

| Attribute | |||||||

| Functio-spatial structure | Isolation of the garden from its surroundings, creating a separate, intimate space | YES/NO (0.5) | YES (1) | YES (1) | NO (0) | NO (0) | YES (1) |

| Siting in a place that retains fragrances and sounds inside the garden | YES (1) there is a hill near the garden that shelters it from one side | YES (1) plants located around the outer rim of the garden shelter it from draughts | YES (1) the garden is surrounded by solid fences and walls | YES/NO (0.5) the garden is in a depressed area, but has no buffer greenery to protect it from draughts | YES/NO (0.5) only partially protected | NO (0) | |

| Internal space and architectural form design | Garden complexity, presence of various garden interiors, proper path system | YES/NO (0.5) interesting path course, no interiors for longer stays | YES (1) the garden is divided into interiors where one can sit and stay longer | YES/NO (0.5) the layout is simple, the path encircles a lawn, but plant pots are only on one side | YES (1) the garden has varied interiors and each has rest spaces | YES/NO (0.5) there are diverse interiors but no paths, some paths have dead ends, little room to sit among the plants | YES/NO (0.5) the path runs through the garden’s centre, which allows easy access to its every part; there are two entrances |

| Legibility of composition | YES/NO (0.5) the composition is not entirely legible, there are dead-ended side paths | YES (1) a clear central path with side paths | YES (1) legible, geometric composition | YES/NO (0.5) consists of several sections, which appear isolated from each other | YES/NO (0.5) consists of several sections which do not appear coherent | YES/NO (0.5) consists of several sections with poor compositional linkages | |

| Presence of water, especially water in motion | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | YES (1) there is a fountain | NO (0) | YES (1) there is a fountain in the form of water jets | |

| Plant sensory impact on each of the senses | YES/NO (0.5) mostly a scent-based garden | YES (1) each of the five senses is highlighted in a separate part of the garden | YES (1) plants in pots provide a diverse range of sensations, they can also be tasted | YES/NO (0.5) various plants that induce sensory experiences, no experiences based on taste | YES/NO (0.5) numerous fragrant plants and fruit-bearing bushes, one can hear the rustle of grass and the sound of gravel, but touch is not stimulated | NO (0) | |

| Intensity of plant sensory impact (e.g., diversity of species, large spaces, elevated beds) | YES (1) large patches of fragrant plants situated along paths | YES (1) wealth of species and strains; plants also placed in pots built into benches | YES (1) plants elevated and placed in large pots | YES (1) sensory path surrounded by sensory active plants | YES/NO (0.5) presence of fragrant plants in isolated areas, but difficult to reach and without seats | NO (0) absent | |

| Other sensory active elements (e.g., labyrinth, sensory path) | YES (1) sensory path and labyrinths near the garden | YES (1) small sensory path | NO (0) absent | YES (1) sensory path | YES/NO (0.5) observation deck on roof, with a gravel surface, but only accessible via stairs | YES (1) labyrinth | |

| Placemaking | Ability to personalise the space | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) |

| Ability to animate the space | YES/NO (0.5) lessons for children, the youth, or adults in the open | YES (1) a green meadow and a tent from living willow branches form a place for play and recreation | YES (1) multimedia presentations, films on the museum wall (chairs laid out on the lawn) | YES/NO (0.5) small tables where one can play board games or chess | NO (0) | YES (1) potential to use one’s imagination and engage in various forms of play | |

| Artistic creations | NO (0) | YES (1) white cubes that act as seats | YES (1) the Museum wall has an artistic expression | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | |

| Special indications for use that facilitate experiencing the garden from up close | NO (0) | YES (1) one can taste fruits | YES (1) one can taste herbs | NO (0) | YES (1) one can taste fruits | YES (1) one can directly use all the equipment, including the fountain | |

| Sustainability criteria | Biodiversity preservation: use of domestic plant species and plants attractive to various groups of animals, creating habitats for animals | YES/NO (0.5) some plants are attractive to butterflies or other insects | YES (1) introduction of plants attractive to the hymenoptera species, plants with fruit for birds; bird habitats | YES/NO (0.5) intentional use of species attractive to species of hymenoptera | YES/NO (0.5) some plants are attractive to butterflies or other insects | YES/NO (0.5) some plants are attractive to insects | NO (0) |

| Sustainable water management, e.g., stormwater collection and use | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | |

| Natural energy sources | NOT APPLICABLE—no electrical appliances | NOT APPLICABLE—no electrical appliances | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | NO (0) | |

| Natural garden maintenance methods | No data | No data | YES (1) | No data | No data | No data | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz, I.; Moszkowicz, Ł.; Porada, K. Evolution of the Concept of Sensory Gardens in the Generally Accessible Space of a Large City: Analysis of Multiple Cases from Kraków (Poland) Using the Therapeutic Space Attribute Rating Method. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115904

Krzeptowska-Moszkowicz I, Moszkowicz Ł, Porada K. Evolution of the Concept of Sensory Gardens in the Generally Accessible Space of a Large City: Analysis of Multiple Cases from Kraków (Poland) Using the Therapeutic Space Attribute Rating Method. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):5904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115904

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrzeptowska-Moszkowicz, Izabela, Łukasz Moszkowicz, and Karolina Porada. 2021. "Evolution of the Concept of Sensory Gardens in the Generally Accessible Space of a Large City: Analysis of Multiple Cases from Kraków (Poland) Using the Therapeutic Space Attribute Rating Method" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 5904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115904

APA StyleKrzeptowska-Moszkowicz, I., Moszkowicz, Ł., & Porada, K. (2021). Evolution of the Concept of Sensory Gardens in the Generally Accessible Space of a Large City: Analysis of Multiple Cases from Kraków (Poland) Using the Therapeutic Space Attribute Rating Method. Sustainability, 13(11), 5904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115904