“I am Delighted!”: The Effect of Perceived Customer Value on Repurchase and Advocacy Intention in B2B Express Delivery Services

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. B2B Customer Perceived Value

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. Customer Perceived Value and B2B Customer Satisfaction

2.2.2. Customer Perceived Value and B2B Customer Trust

2.2.3. Customer Perceived Value and B2B Switching Costs

2.2.4. Customer Perceived Value and B2B Repurchase Intent

2.2.5. Customer Perceived Value and B2B Recommendation Intention

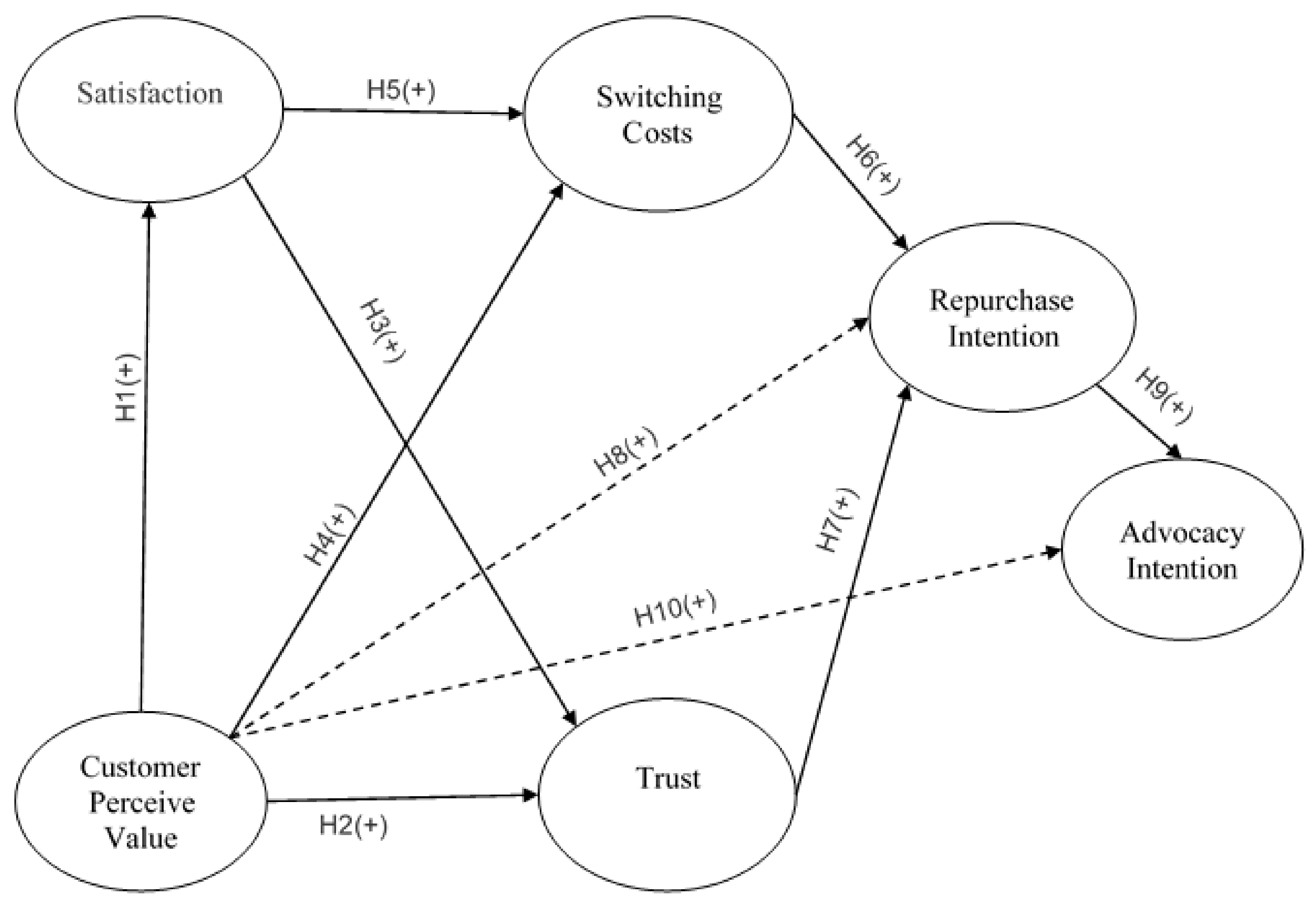

2.3. Conceptual Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measurement Scales

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the Measurement Model

4.2. Analysis of the Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Practical Applications

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Setiyawati, S.; Haryanto, B. Why Customers Intend to Use Express Delivery Services? Case Stud. Bus. Manag. Macrothink Inst. 2016, 3, 56–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donthu, N.; Gustafsson, A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, J.A.; Ballantine, P.W. What do we mean by sustainability marketing? J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 277–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, N.D.; Phan, A.C. Determinants of customer satisfaction and loyalty in Vietnamese life-insurance setting. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DBK INFORMA Observatorio Sectorial. Available online: https://www.dbk.es/es/estudios/15533/summary (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Pettersson, A.I.; Segerstedt, A. Measuring supply chain cost. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schniederjans, A.; Schniederjans, D.; Schniederjans, M. Outsourcing Management Information System; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- König, A.; Spinler, S. The effect of logistics outsourcing on the supply chain vulnerability of shippers. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2016, 27, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, S.M. Entre regulación y competencia: Revisión institucional de la Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia CNMC. Ph.D. Thesis, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lashley, C.; Chibili, M.N. Pocket Guide for Hospitality Managers, 1st ed.; Noordhoff Uitgevers: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rauyruen, P.; Miller, K.E. Relationship quality as a predictor of B2B customer loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čater, B.; Čater, T. Relationship-value-based antecedents of customer satisfaction and loyalty in manufacturing. JBIM 2009, 24, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahan, A.M.; Porter, M.E. How much does industry matter, really? SMJ 1997, 18, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahan, A.M. Competition, Strategy, and Business Performance. CMR 1999, 41, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.T. Factors affecting online food delivery service in Bangladesh: An empirical study. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon-itt, S. Managing self-service technology service quality to enhance e-satisfaction. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2015, 7, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Stolze, H.J.; Mollenkopf, D.A.; Flint, D.J. What is the right supply chain for your shopper? Exploring the shopper service ecosystem. J. Bus. Logist. 2016, 37, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Payne, A.; Ballantyne, D. Relationship Marketing; Taylor & Francis: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, F.; Herrmann, A.; Morgan, R.E. Gaining competitive advantage through customer value oriented management. JCM 2001, 18, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polas, R.H.; Imtiaz, M.; Saboor, A.; Hossain, N.; Javed, M.A.; Nianyu, L. Assessing the Perceived Value of Customers for being Satisfied towards the Sustainability of Hypermarket in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 6, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.H.; Huang, W. Bulls, bears and market sheep. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1990, 14, 299–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B. Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S.P.; Tzempelikos, N.A.; Chatzipanagiotou, K. The relationships of customer-perceived value, satisfaction, loyalty and behavioral intentions. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2007, 6, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S. Measuring service quality in B2B services: An evaluation of the SERVQUAL scale vis-à-vis the INDSERV scale. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2005, 19, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Customer retention in the medical tourism industry: Impact of quality, satisfaction, trust and price reasonableness. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbango, P. The role of perceived value in promoting customer satisfaction: Antecedents and consequences. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1684229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Helkkula, A.; Kelleher, C. Circularity of customer service experience and customer perceived value. J. Cust. Behav. 2010, 9, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, O.S.; Kassar, A.N.; Loureiro, S.M.C. Value get, value give: The relationships among perceived value, relationship quality, customer engagement, and value consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Thompson, C.J. Consumer culture theory (CCT): Twenty years of research. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 31, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jin, N.; Line, N.D.; Goh, B. Experiential value, relationship quality, and customer loyalty in full-service restaurants: The moderating role of gender. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.S.; Hapsari, R.D.V.; Yulianti, I. Experience quality and hotel boutique customer loyalty: Mediating role of hotel image and perceived value. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.J.; Liang, R.D. Effect of experiential value on customer satisfaction with service encounters in luxury-hotel restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V.; Sherry, J.F.; DeBerry-Spence, B.; Duhachek, A.; Nuttavuthisit, K.; Storm, D. Themed flagship brand stores in the new millennium: Theory, practice, prospects. J. Retail. 2002, 78, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environment. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A. Rethink brand experience. Brand Strategy 2003, 174, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsson, S.H.; Kale, S.H. The experience economy and commercial experiences. TMR 2004, 4, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, T.; Dhanya, A. Impact of product quality, service quality and contextual experience on customer perceived value and future buying intentions. EJBMR 2012, 3, 307–315. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Q.T.; Tran, X.P.; Misra, S.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Damaševičius, R. Relationship between convenience, perceived value, and repurchase intention in online shopping in Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, L.Y.; Chen, K.Y.; Chen, P.Y.; Cheng, S.L. Perceived value, transaction cost, and repurchase-intention in online shopping: A relational exchange perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2768–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, D.M.; Gremler, D.D.; Washburn, J.H.; Carrión, G.C. Service value revisited: Specifying a higher-order, formative measure. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Po Lo, H.; Chi, R.; Yang, Y. An integrated framework for customer value and customer-relationshipmanagement performance: A customer-based perspective from China. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2004, 14, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minarti, S.N.; Segoro, W. The influence of customer satisfaction, switching cost and trusts in a brand on customer loyalty—The survey on student as IM3 users in Depok, Indonesia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 143, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leninkumar, V. The relationship between customer satisfaction and customer trust on customer loyalty. IJARBSS 2017, 7, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, J.; Droge, C. Service quality, trust, specific asset investment, and expertise: Direct andindirect effects in a satisfaction-loyalty framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, F.D.O.; Ladeira, W.J.; Sampaio, C.H. The role of satisfaction in fashion marketing: A meta-analysis. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2018, 9, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M. Internet banking service quality and its implication on e-customer satisfaction and e-customer loyalty. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Measurement and evaluation of satisfaction processes in retail settings. J. Retail. 1981, 57, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.W.; Fornell, C.; Lehmann, D.R. Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsetova, A.; Enimanev, K. A Study on Customer Satisfaction of Courier Services in Bulgaria. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2014, 6, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Otsetova, A. Relationship between logistics service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty in courier services industry. Manag. Educ. 2017, 13, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kesari, B.; Atulkar, S. Satisfaction of mall shoppers: A study on perceived utilitarian and hedonic shopping values. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adly, M.I. Modelling the relationship between hotel perceived value, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, M. The impact of HRM practices on service quality, customer satisfaction and performance in the Indian hotel industry. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.L. Service quality and the training of employees: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikhamn, W. Innovation, sustainable HRM and customer satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Fan, W.; Zhou, M. Social presence, trust, and social commerce purchase intention: An empirical research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Min, Q.; Han, S. Understanding the effects of trust and risk on individual behavior toward social media platforms: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Narus, J.A. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Deshpande, R.; Zaltman, G. Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganesan, S. Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; Hunt, S. The commitment-trust theory of relationships marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Weitz, B. The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askariazad, M.H.; Babakhani, N. An application of European Customer Satisfaction Index (ECSI) in Business to Business (B2B) Context. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2015, 30, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Li, J.; Tangpong, C.; Clauss, T. The interplays of coopetition, conflicts, trust, and efficiency process innovation in vertical B2B relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 85, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, G.S.; Eberle, L.; Bebber, S. Perceived value, reputation, trust, and switching costs as determinants of customer retention. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2015, 14, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Lankton, N.K.; Nicolaou, A.; Price, J. Distinguishing the effects of B2B information quality, system quality, and service outcome quality on trust and distrust. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghkhah, A.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Asgari, A.A. Effects of Customer Value And Service Quality on Customer Loyalty: Mediation Role of Trust and Commitment in Business-To-Business Context. Manag. Res. Pr. 2020, 12, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Blut, M.; Evanschitzky, H.; Backhaus, C.; Rudd, J.; Marck, M. Securing business-to-business relationships: The impact of switching costs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 52, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burnham, T.A.; Frels, J.K.; Mahajan, V. Consumer switching costs: A typology, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandos Herrera, C.; Puyuelo Arilla, J.M. La generación de lealtad a un destino de turismo gastronómico como factor clave en el desarrollo rural. Cuad. Aragon. Econ. 2013, 23, 47–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lesmono, S.U.; Santoso, T.; Wijaya, S.; Jie, F. The Effect of Switching Cost and Product Return Management on Repurchase Intent: A Case Study in the B2B Distribution Channel Context in Indonesia. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 9, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett, D.; Hopkins, C.D.; Williams, Z. Buyer dependence in B2B relationships: The role of supplier investments, commitment form, and trust. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.; Hu, T.; Yang, S. Effects of inertia and satisfaction in female online shoppers on repeat-purchase intention: The moderating roles of word-of-mouth and alternative attraction. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2013, 23, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, J.; Lajevardi, M.; Fakharmanesh, S. An Integrated Model in Customer Loyalty Context: Relationship Quality and Relationship Marketing View. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2013, 7, 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Hellier, P.K.; Geursen, G.M.; Carr, R.A.; Rickard, J.A. Customer repurchase intention: A general structural equation model. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1762–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiu, C.M.; Lin, H.Y.; Sun, S.Y.; Hsu, M.H. Understanding customers’ loyalty intentions towards online shopping: An integration of technology acceptance model and fairness theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2009, 28, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiders, K.; Voss, G.B.; Grewal, D.; Godfrey, A.L. Do satisfied customers buy more? Examining moderating influences in a retailing context. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A. Examining the impact of perceived service quality dimensions on repurchase intentions and word of mouth: A case from software industry of Pakistan. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 16, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1993, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, B.; Gale, B.T.; Wood, R.C. Managing Customer Value: Creating Quality and Service that Customers can See; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Chen, Y. A study on the influence of purchase intentions on repurchase decisions: The moderating effects of reference groups and perceived risks. Tour. Rev. 2009, 64, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, S. Mediating role of customer value between Innovative Self-Service Technology (ISST) factors and online repurchase intention. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2016, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Suryadi, N.; Suryana, Y.; Komaladewi, R.; Sari, D. Consumer, customer and perceived value: Past and present. Acad. Strat. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, S.; Chen, C.W. The influences of relational benefits on repurchase intention in service contexts: The roles of gratitude, trust and commitment. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, M.T.M. The factors affect organization customer perceived value and repurchase intention-A empirical study of professional B2B general insurance service in Vietnam. Ph.D. Thesis, International University-HCMC, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, S.; Wei, J. Consumer’s intention to use self-service parcel delivery service in online retailing: An empirical study. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 500–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garver, M.S.; Williams, Z.; Goffnett, S.P.; Gibson, B.J. Parcel shipping: Understanding the needs of business shippers. J. Transp. Manag. 2016, 26, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y. Investigating antecedents of consumers’ recommend intentions and the moderating effect of switching barriers. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.W.; Cowles, D.L.; Tuten, T.L. Service recovery: Its value and limitations as a retail strategy. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1996, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B. How word of mouth communication varies across service encounters. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2011, 21, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawdhary, R.; Dall’Olmo Riley, F. Investigating the consequences of word of mouth from a WOM sender’s perspective in the services context. J. Mark. Manag. 2015, 31, 1018–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simpson, P.M.; Siguaw, J.A. Destination Word of Mouth: The Role of Traveler Type, Residents, and Identity Salience. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvisi, M.; Pianeti, R.; Urga, G. Modelling Financial Markets Comovements during Crises: A Dynamic Multi-Factor Approach. Adv. Econ. 2016, 35, 317–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reyes-Menendez, A.; Saura, J.R.; Martinez-Navalon, J.G. The impact of e-WOM on hotels management reputation: Exploring tripadvisor review credibility with the ELM model. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 68868–68877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.C.Y.; Malhotra, N.K.; Alpert, F. A two-dimensional model of trust-value-loyalty in service relationships. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 26, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Leonard, L.N. Factors Influencing Buyer’s Trust in Consumer-to-Consumer E Commmerce. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2014, 54, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K. Consequences of customer advocacy. J. Strat. Mark. 2013, 21, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, F.; Cheema, S. Customer satisfaction and customer perceived value and its impact on customer loyalty: The mediational role of customer relationship management. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2017, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nyadzayo, M.W.; Khajehzadeh, S. The antecedents of customer loyalty: A moderated mediation model of customer relationship management quality and brand image. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.A.; Baker, T.L. An assessment of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in the formation of consumers’ purchase intentions. J. Retail. 1994, 70, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decision. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, S.; Cheng, Y. Improve Communication Quality by Understanding Customer Switching Behavior in China’s Telecom Sector. Ibusiness 2016, 8, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inman, J.J.; Nikolova, H. Shopper-facing retail technology: A retailer adoption decision framework incorporating shopper attitudes and privacy concerns. J. Retail. 2017, 93, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Y.W.; Kim, D.J. Assessing the effects of consumers’ product evaluations and trust on repurchase intention in e-commerce environments. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H. Effect of image, satisfaction, trust, love, and respect on loyalty formation for name-brand coffee shops. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, I.; Mensah, R.D. Effects of Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction on Repurchase Intention in Restaurants on University of Cape Coast Campus. JTHSM 2018, 4, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghia, H.T.; Olsen, S.O.; Trang, N.T.M. Shopping value, trust, and online shopping well-being: A duality approach. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B.; Maroofi, F.; Ahmadizad, A. The investigating of cognitive and affective two-dimensional pattern between consumer trust, perceived value and behavioral loyalty in Iran governmental and non-governmental insurance areas. Bankacılık Ve Sigortacılık Araştırmaları Derg. 2017, 2, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamam, N.M. Does Re-Enroll Intention Mediate Relationship Between Perceived Value, Student Satisfaction and Advocacy Behavior? A Perspective of Private Higher Education. IJARES 2020, 2, 130–141. [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon, E.E. Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in European management research: A realist perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Bridging design and behavioral research with variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. On comparing results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Five perspectives and five recommendations. Mark. ZFP 2017, 39, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Partial least squares path modeling: Quo vadis? Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, A.; Deckers, T.; Dohmen, T.; Falk, A.; Kosse, F. The relationship between economic preferences and psychological personality measures. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2012, 4, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W. Bootstrap cross-validation indices for PLS path model assessment. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3 [Software]; SmartPLS: Bönningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Carrión, G.; Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.L. Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modeling: Guidelines and empirical examples. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Thompson, R.; Higgins, C. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, G.V. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Peterson, R.T. Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: The role of switching costs. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C. A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Feick, L. The impact of switching costs on the customer satisfaction-loyalty link: Mobile phone service in France. J. Serv. Mark. 2001, 15, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, W.D. Satisfaction is nice, but value drives loyalty. Mark. Res. 1999, 11, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N.; Patterson, P.G. Switching costs, alternative attractiveness and experience as moderators of relationship commitment in professional, consumer services. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2000, 11, 470–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Lemon, K.N. A dynamic model of customers’ usage of services: Usage as an antecedent and consequence of satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ram, S.; Jung, H.S. How product usage influences consumer satisfaction. Mark. Lett. 1991, 2, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, N.U.; Aslam, N.; Gulzar, A. Sustainable service quality and customer loyalty: The role of customer satisfaction and switching costs in the Pakistan cellphone industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nenadál, J.; Vykydal, D.; Tylečková, E. Complex Customer Loyalty Measurement at Closed-Loop Quality Management in B2B Area—Czech Example. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenitzerová, M.; Gaňa, J. Customer satisfaction and loyalty as a part of customer-based corporate sustainability in the sector of mobile communications services. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heinonen, K.; Strandvik, T. Reframing service innovation: COVID-19 as a catalyst for imposed service innovation. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 32, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.J.; Lee, J.Y. South Korea’s proactive approach to the COVID-19 global crisis. Psychol. Trauma. 2020, 12, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eggert, A.; Ulaga, W. Customer perceived value: A substitute for satisfaction in business markets? J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2002, 17, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, R.; Dingus, R.; Hu, M.Y.; Krush, M.T. Social media: Influencing customer satisfaction in B2B sales. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 53, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Sreejesh, S.; Bhatia, S. Service quality versus service experience: An empirical examination of the consequential effects in B2B services. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 82, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Ko, E.; Joung, H.; Kim, S.J. Chatbot e-service and customer satisfaction regarding luxury brands. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item Scales 1 | REP | ADV | SAT | SC | CPV | TRU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I will probably use my express delivery provider again. | 0.899 | |||||

| I have the intention to purchase the services of my express delivery provider in the future. | 0.912 | |||||

| I may use my express delivery provider’s services very frequently in the future. | 0.912 | |||||

| I will say positive things about my express delivery provider to other people. | 0.939 | |||||

| I will recommend my express delivery provider to other people who ask me. | 0.933 | |||||

| I will encourage friends and family to do business with my express delivery supplier. | 0.874 | |||||

| I am satisfied with the services of my express delivery provider. | 0.873 | |||||

| Overall, I am satisfied when using the services of my express delivery provider. | 0.921 | |||||

| Using the services of this express delivery provider is a satisfying experience. | 0.910 | |||||

| My choice to use my express delivery provider was the right one. | 0.942 | |||||

| Overall, I am satisfied with my express delivery supplier. | 0.917 | |||||

| I believe I made the right decision in choosing to rely on my express delivery provider for my service needs. | 0.896 | |||||

| Certainly if I switch to another express delivery provider it probably would not be as good as the current one. | 0.770 | |||||

| I am not sure if switching to another express delivery provider would be good for me. | 0.706 | |||||

| I already know the staff; changing express delivery providers would be like starting from scratch. | 0.720 | |||||

| My express delivery supplier has a strong social reputation. | 0.712 | |||||

| My express delivery provider’s employees are available to help my company achieve my objectives. | 0.874 | |||||

| My express delivery supplier’s employees are available to add value to my business. | 0.898 | |||||

| My express delivery supplier’s employees are available to help improve my company’s sales and image. | 0.915 | |||||

| I am satisfied with my express delivery supplier’s level of innovation and leadership position in their field. | 0.789 | |||||

| In our relationship, I can always rely on my express delivery supplier. | 0.905 | |||||

| In our relationship, my express delivery supplier always gets it right. | 0.911 | |||||

| In our relationship, my express delivery supplier has high reliability and integrity. | 0.911 |

| Scales 1 | Mean | SD | CA | Rho A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REP | 5.145 | 1.311 | 0.893 | 0.893 | 0.934 | 0.824 |

| ADV | 5.036 | 1.312 | 0.905 | 0.936 | 0.940 | 0.838 |

| SAT | 5.198 | 1.106 | 0.958 | 0.960 | 0.967 | 0.828 |

| SC | 4.696 | 1.414 | 0.707 | 0.712 | 0.818 | 0.529 |

| CPV | 4.626 | 1.393 | 0.892 | 0.892 | 0.926 | 0.758 |

| TRU | 4.735 | 1.251 | 0.895 | 0.896 | 0.934 | 0.826 |

| Scales 1 | REP | ADV | SAT | SC | CPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REP | − | ||||

| ADV | 0.778 | − | |||

| SAT | 0.825 | 0.790 | − | ||

| SC | 0.683 | 0.722 | 0.722 | − | |

| CPV | 0.534 | 0.624 | 0.708 | 0.853 | − |

| TRU | 0.674 | 0.675 | 0.833 | 0.775 | 0.830 |

| Effects on Endogenous Variables 1 | Path Coeff. | Confidence Intervals (97.5%) | Significance of Effect (p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5%CIlo | 97.5%CIhi | |||

| CPV → SAT (H1) | 0.661 | 0.562 | 0.759 | Yes (0.000) |

| CPV → TRU (H2) | 0.417 | 0.292 | 0.542 | Yes (0.000) |

| SAT → TRU (H3) | 0.499 | 0.343 | 0.655 | Yes (0.000) |

| CPV → SC (H4) | 0.287 | 0.120 | 0.454 | Yes (0.001) |

| SAT → SC (H5) | 0.497 | 0.356 | 0.639 | Yes (0.000) |

| SC → REP (H6) | 0.296 | 0.119 | 0.474 | Yes (0.001) |

| TRU → REP (H7) | 0.414 | 0.236 | 0.593 | Yes (0.000) |

| REP → ADV (H9) | 0.714 | 0.619 | 0.810 | Yes (0.000) |

| Effects on Endogenous Variables 1 | Path Coeff. | Confidence Intervals (97.5%) | Significance of Effect (p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5%CIlo | 97.5%CIhi | |||

| CPV → TRU → REP (H8, Full mediation) | 0.173 | 0.095 | 0.250 | Yes (0.000) |

| CPV → TRU → REP → ADV (H10, Partial mediation) | 0.123 | 0.064 | 0.182 | Yes (0.000) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Correa, C.; Alarcón, D.; Cepeda, I. “I am Delighted!”: The Effect of Perceived Customer Value on Repurchase and Advocacy Intention in B2B Express Delivery Services. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116013

Correa C, Alarcón D, Cepeda I. “I am Delighted!”: The Effect of Perceived Customer Value on Repurchase and Advocacy Intention in B2B Express Delivery Services. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116013

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorrea, Carlos, David Alarcón, and Ignacio Cepeda. 2021. "“I am Delighted!”: The Effect of Perceived Customer Value on Repurchase and Advocacy Intention in B2B Express Delivery Services" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116013

APA StyleCorrea, C., Alarcón, D., & Cepeda, I. (2021). “I am Delighted!”: The Effect of Perceived Customer Value on Repurchase and Advocacy Intention in B2B Express Delivery Services. Sustainability, 13(11), 6013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116013