1. Introduction

The origin story of the outbreak of COVID-19 is well-known worldwide, but to date, there has been no clear evidence that reveals the reasons for it [

1]. Nevertheless, the pandemic has had consequences beyond the spread of the disease itself, as it constitutes an unprecedented challenge with very severe socio-economic consequences [

2,

3]. Furthermore, the impact of this crisis and a country’s ability to cope with it vary significantly depending on the country and its level of development and wellbeing [

4,

5]. While some countries are better prepared to deal with the pandemic and its impacts, others are still struggling. The world has been hard-hit by COVID-19, and consequently, the side effects of the pandemic have greatly affected society [

6,

7].

The pandemic has had enormous global effects that have left no individual, institution or economy untouched. This unexpected circumstance has changed our lives in many ways, including the way we work. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic has given us massive insights on how technology can play a vital role in organizations, our work–life balance and the future of flexible working [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The literature shows how the workplace has changed during the COVID-19 crisis. However, it is also worth noting that this sudden shift comes with the risk of a new kind of burnout. In this direction, there are already some studies in the literature that encourage employers to study wellness (mental health) in the workplace during the COVID-19 pandemic [

12,

13,

14].

In 1976, Dr. Bill Hettler, co-founder of the National Wellness Institute in the US, defined wellness as the pursuit of continued growth and balance in six dimensions. These dimensions encompass one’s social/emotional, spiritual, environmental, occupational, intellectual, and physical wellbeing [

15]. The concepts of wellness and well-being have been evolving in the last decades. Amartya Sen deepens the concept of well-being and human development in his “human development theory from a capability approach”. He considers well-being to be the process of widening capacities, liberties, and opportunities of individuals to live a life that is worth living [

16]. In addition, he introduces the concept of functionings as “the various things a person may value doing or being” [

17]. In this context, it has to be noted that attention must be given to a variety of dimensions included in the definition of well-being. Some of them, such as education, health, and income, have been widely accepted in the literature even from different perspectives [

18,

19,

20]. The neglect of any of these dimensions over time will adversely affect others and ultimately harm one’s well-being and quality of life. Specifically, this paper describes an example of how to elicit personal perceptions about weaknesses and limitations that could be challenges and obstacles in one’s life and consequently hinder one’s wellbeing. Ultimately, one needs the ability to put functionings into action to achieve a more tolerable life and well-being [

16].

Turning to the issue of health as a basic component of well-being, several researchers have shown that health issues (or poor health) and their impact on various fields of study have been a hot topic during the COVID-19 pandemic [

21,

22,

23]. For instance, in the field of healthcare services, the literature shows that working in areas with a high incidence of infection was significantly associated with higher stress and psychological disturbances [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Furthermore, the pandemic has hit the agriculture and food sector with joblessness, which is not only affecting people economically but also causing other social and psychological stress [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Finally, in the educational sector, instructors from elementary school to higher education levels have had to adapt to the world of distance education, as all learners have faced educational institutions’ closures [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Most instructors and their organizations have embraced this challenge, although in many cases these professionals lack the skills and equipment to provide distance education effectively [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43], especially in developing countries [

44,

45].

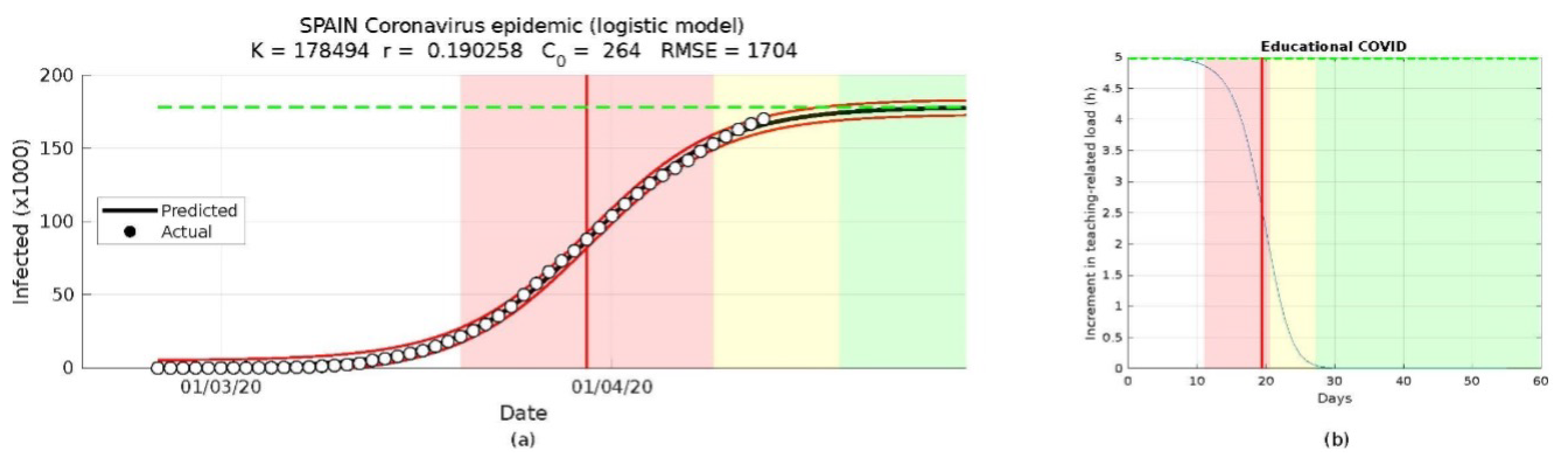

This proposal aims to shed light on how face-to-face universities have mitigated the impact of the ongoing pandemic on higher education systems. The authors of this study took inspiration from epidemiological studies where researchers graphically represent the propagation analysis of COVID-19 by showing the rate of people infected day by day [

46,

47,

48]. As an example,

Figure 1a, shows the predicted Spanish epidemiological curve of COVID-19, and for that purpose it uses a sigmoidal model (where K, r, and C

are parameters of the logistic curve and RMSE indicates the performance of this logistic model) [

49]. The data came from the Spanish Ministry of Health. Similarly, this investigation offers a hypothetical educational COVID-19 curve model under the assumption that a sudden change in the teaching scenario (from face-to-face to online) increased the teachers’ workload relative to their teaching duties during the COVID-19 lockdowns (

Figure 1b). The educational COVID-19 curve has been illustrated in a time series in which the x-axis represents the time period and the y-axis represents the additional workload hours. The main difference in modeling terms between the COVID-19 epidemic curve and the educational COVID curve lies in the logistic growth rate parameter that is associated with the logistic functions of the two phenomena. This parameter is positive in the first scenario, and it is negative in the second scenario.

The main objective of this research is to define the strengths and weaknesses of the function of teaching in higher education and face-to-face contexts. Due to the unexpected circumstances, teaching shifted from face-to-face lectures to online classes. We offer some guidelines for traditional universities so they can overcome future weaknesses and encourage their strengths when teaching in an online context (as this new environment or blended model has come to stay in a majority of higher education institutions at least in the medium term). Methodologically speaking, this analysis is carried out using a validated research questionnaire that defines the teaching duties of an online instructor in the 21st century [

50]. The purpose is to assess the teachers’ skills in conventional settings when teaching in scenarios for which they have not been trained (online environments). Additionally, this research work analyzes the type of support (either internal or external to their corresponding universities) these facilitators received during their teacher professional development amid this unpredictable event.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the baseline questionnaire adopted as the theoretical framework of the study (consequently, the research variables analyzed in the study).

Section 3 details the methodological approach adopted in the manuscript, including the data acquisition procedure, a description of the participants involved in the study, and the statistical analysis that was performed. The empirical (statistical) results we obtained are reported in

Section 4. Furthermore, the discussion section provides a theoretical analysis of the empirical results (with a connection to the existing literature) and a complete description of the implications of the empirical results for the educational community (

Section 5). Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the main findings of this study.

2. Theoretical Framework

This study borrows, as its theoretical framework, a recently published educational model [

50,

51] that defines the roles of instructors in higher education online learning environments in the 21st century. The baseline educational model defines those roles using a sequential methodological approach with the following three steps: (i) a systematic literature review in the field, (ii) in-depth interviews with 6 experts on the topic (teaching tasks and roles in online environments), and (iii) a pilot study that analyses students’ viewpoints. Additionally, the model was also validated quantitatively through a sample of 925 online students.

The selected educational approach perfectly fits into this research for different reasons [

50,

52]. First, the present study mainly focuses on the teaching duty of instructors in higher online educational environments. Indeed, the adopted study recognizes that a college instructor has three main professional functions (teaching, management/service and research), and it centers its attention exclusively on the teaching function of the instructors. Second, our target group consists of instructors from in-person learning environments who suddenly switched to virtual instruction. As claimed in [

50,

51], the functions of teachers in virtual and face-to-face learning environments are different. As a result, the search criteria for selecting a framework that defines the instructors’ roles were limited to research works belonging to the field of eLearning environments. Below, a brief description of the components (instructors’ roles) in the adopted framework is presented.

The pedagogical role (PR). First, the authors of the study include the pedagogical attributes of an instructor as an essential part of his or her teaching tasks. They clarified that this main construct includes the following sub-roles: (i) professionals, (ii) content experts, and (iii) resource material creators and study guide producers. That is, instructors should shift their roles from lecturers to facilitators who provide resources, monitor progress and encourage students to develop a problem-solving-oriented mindset. In addition, instructors should be content facilitators with both an excellent mastery of their subject matter and continuous concern to update their knowledge about the subject (lifelong learners). Furthermore, instructors should provide (from the beginning of the semester) adequate, useful and compressible material to enable the students to succeed, as well as the subject’s long-term goals.

The course designer role (CDR): It is commonly known that careful planning before the lessons themselves not only makes teaching easier and more enjoyable but also facilitates student learning. The authors reinforced this belief in their study (i.e., their belief that successful courses require careful planning) and stressed the idea of adding continual revisions to the course structure for flexibility and negotiation if necessary. Additionally, it is important to note that the results we are using opened the debate on why some authors include the designer role as part of the pedagogical one, whereas others divide the tasks that encompass these roles between two different roles. As shown in the original study, there are some online courses that are designed by experts (instructional designers) but taught by different people (instructors); in other online courses, the same person is in charge of both tasks.

The social role (SR): The authors highlighted the importance of promoting communication in online learning practices, especially as there is no physical classroom to promote relationships between individuals. They also pointed out the importance of the role under the umbrella of the 21st century framework of learning, where communication and teamwork skills are key competencies that need to be developed by students. This role includes live interactions supported by synchronous learning systems (SRSC) as well as interactivity with asynchronous tools (SRAC). The authors specifically underlined the importance of fostering the relationships between students and the instructor (group relationship) and each student and the instructor (individual relationship).

The life-skills promoter role (LSPR). In line with the UNESCO humanistic vision of learning and the centrality of education as a basic component of human wellbeing [

5,

19,

53], the authors suggested incorporating this new role into the 21st century framework of learning. They emphasized that all educators should focus their attention on helping their students to succeed in life beyond training students with specific knowledge. As mentioned in the original study, integrating these skills into the curriculum is a fundamental principle for reshaping education and helping students to reach their full potential, not only as academic achievers but also as human beings. This idea is in line with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4.7 of Agenda 2030, which was agreed in 2015 by the United Nations (Resolution General Assembly—

https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E; accessed on 19 May 2021). This goal states that by 2030,

all learners should have acquired the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development (Agenda 2030—SDG4:

https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4; accessed on 19 May 2021).

The technical role (TR). As pointed out by the authors, this role has been considered as a key element in the teaching function of online instructors since the very beginning of research on this topic. The authors also claimed that it was very important to have the right support and technical assistance from institutions, as there exists a continuous advancement of technology. Ultimately, the authors suggested paying attention to this role to prevent student frustration and possible dropping out due to the technical factors that exist in online learning.

The Managerial role (MR): Finally, the authors underlined the evolving nature of managerial roles in the literature. They mentioned that this role has been extensively studied in the online learning literature by different authors and from different perspectives. Regarding the nature of the role, these authors highlighted that facilitators should use management not to control students, but to help them actively participate in the learning process. In the view of the authors, this role implies ensuring that students have the right rules and information to participate fully in the courses. Thus, this role includes tasks such as setting the minimal ethical norms, procedural rules (deadlines) and decision-making norms. The authors suggested visibly incorporating these classroom management rules to help students organize their time and learning.

As stated in the previous section, the theoretical model presented in this study includes not only the above instructors’ roles but also the support that those instructors received during the transition from face-to-face to online learning. Instructional support is conceived in this study as the assistance that faculty members received to help them succeed in their teaching duties during the shifting of the educational model. Specifically, this study incorporates two types of assistance. First, formal support (FS), which refers to the help educators could receive from any official body inside the university to face the challenges of adapting to online teaching. This type of support includes but is not limited to the following individuals: the dean, head of department, ICT staff and center of innovation. Second, informal support (IS), which refers to the guidance facilitators could receive from non-formal entities or people to deal with the learning and development teaching tasks.

4. Results

This section analyzes the pedagogical online training of the instructors under study and the level of formal and informal support received during the pandemic according to their own perceptions.

Table 1 shows the mean score and standard deviation (

) along with the mean ranking (

) for the components analyzed, which were divided into the two areas of interest previously mentioned. The study has been conducted on three levels: (i) an overall analysis including all of the participants, (ii) a study in which the participants have been divided according to their gender, and (iii) a study segregated by type of discipline (STEM and SSH).

As can be seen in

Table 1, the best performing role (independently of the gender and discipline) was the technical role (with an average score of 5.5000 and a mean ranking of 2.3929 for the data sample including all of the participants). The second-best performing role for the overall study was the managerial role (with a mean score of 4.5000 and a mean ranking of 3.3929). It is worth mentioning that according to the instructors’ perceptions, the two roles that were harder to implement via online lectures were those that incorporate the social part of learning (the social role-synchronous and life skills promoter roles). Regarding the analysis of the support received by instructors, informal technical support was the element with the greatest mean score and ranking. Consistently with the previously-mentioned results, the elements related to the social part of learning are traditionally the ones that receive less support (both formal and informal). Additionally, the instructors tend to report that the informal support they received was more important in overall terms than the formal support (the scores of the elements related to informal support generally had greater values than those associated with formal support).

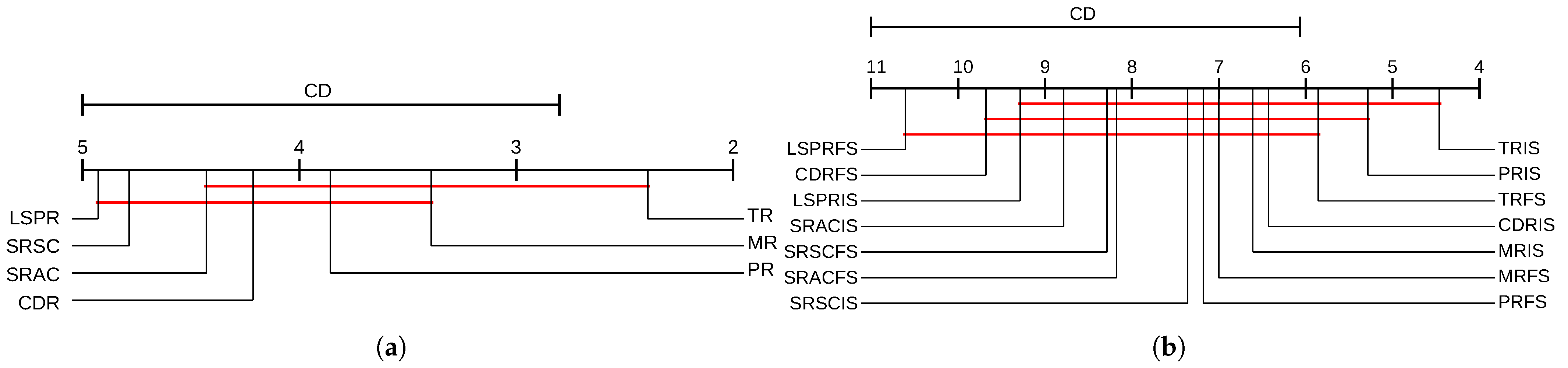

The significance of the empirical results was assessed using non-parametric statistical tests (using the data included in the overall analysis) since a previous evaluation of the average scores obtained in the instructors’ roles and instructors’ support resulted in rejections of the normality and equality of various hypotheses. As previously pointed out, we implemented the Friedman and Nemenyi statistical tests. The Friedman test checked if there were significant differences in the groups of results, while the Nemenyi test was used to detect which of all of the comparable pairs have significant differences. The pre-hoc Friedman test was performed twice with the average ranking obtained in each role and the mean ranking for the instructor’s support. The test showed that there were statistical differences between the scores obtained in the different roles and elements of instructors’ support at a significance level of 5%, as the confidence intervals are and and the F-distribution statistical values are and , respectively. Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected. The null hypothesis stated that all of the roles and elements of instructors’ support performed equally in the mean ranking.

Based on the two previous rejection results, the Nemenyi post-hoc test was used to compare all of the roles and elements of instructors’ support with each other. The Nemenyi test analyzes the performances of different roles or instructors’ support, and it considers a role or element of the instructors’ support to be significantly different if its mean rank differs by at least the critical difference (CD). The results of the two Nemenyi tests for

can be seen in

Figure 3, where the CD is also shown, and the mean ranking of each role or instructor’s support is represented on the scale for each plot. Whenever the mean rankings of the two algorithms differ by more than the CD, significant differences can be assessed.

The results of the Nemenyi tests for show that instructors’ roles were statistically organized (according to their mean rankings) into two groups: (I) the first group encompasses the TR, MR, PR, CDR, and SRAC roles, and (ii) the second group includes the MR, PR, CDR, SRAC, SRSC, and LSPR roles. Regarding the instructors’ support, the elements were statistically clustered in three clusters: the first cluster contains the TRIS, PRIS, TRFS, CDRIS, MRIS, MRFS, PRFS, SRSCIS, SRACFS, SRSCFS, SRACIS, and LSPRIS roles, the second one contains the PRIS, TRFS, CDRIS, MRIS, MRFS, PRFS, SRSCIS, SRACFS, SRSCFS, SRACIS, LSPRIS, and CDRFS roles and the last one has the TRFS, CDRIS, MRIS, MRFS, PRFS, SRSCIS, SRACFS, SRSCFS, SRACIS, LSPRIS, CDRFS, and LSPRFS roles.

6. Conclusions

This research work is in line with studies from the literature that evaluate education in the era of COVID-19. Specifically, this study sheds light on how face-to-face educators have mitigated the impact of the ongoing pandemic on higher education systems. This paper has evaluated the variables these instructors had to deal with to carry out online teaching during coronavirus lockdowns. To this end, a theoretical framework recently published in the field of eLearning contexts has been adapted ad hoc for this study [

50,

51]. Specifically, the performance of the instructors in the following roles has been analyzed in this paper: pedagogical roles, course designer roles, social roles, life-skills promoter roles, technical roles and managerial roles. In addition to these roles, this research also takes into account the support that instructors could receive during the transition from face-to-face instruction to online instruction. For the purposes of this research, the concept of support refers to the assistance that faculty members receive to succeed in their teaching duties during the shifting of the educational model. In particular, this study incorporates two types of assistance: formal support and informal support. While formal support refers to the help educators could receive from any official body inside their university to face the challenges of adapting to online teaching, informal support refers to the guidance facilitators could receive from non-formal entities or people inside and outside of their university to deal with learning and developmental teaching tasks. Methodologically, one-on-one sessions were conducted on a sample of 18 facilitators to analyze the different perceptions of the participants regarding their initial training levels in the different instructors’ roles and the level of support provided formally and informally during the lockdown semester. Results from the Q-sort methodology determined that an instructor’s adaptability to technology is not a major issue, whereas there is a general need for teacher training on embedding life skills into teaching.

The findings from this study have important implications for traditional higher education institutions. Due to unexpected circumstances, these institutions may be forced to shift from face-to-face to online classes or to apply a blended education model in the near future. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a starting point of a huge debate that has highlighted the possibility of future pandemics and global health emergencies. In addition, online and blended pedagogical models are an opportunity in contexts where the traditional physical presence is difficult to achieve for students in distant territories or in economic trouble. International organizations are warning nations to have the right political and financial investments to advance health security, prevent and mitigate future pandemics, and protect our future and the future of generations to come. For this reason, this study focuses on understanding how face-to-face universities have completed their academic courses despite the pandemic and lockdown. This research showed that numerous studies have emerged in the field of online education since March 2020 regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. However, cautious attention should be paid when generalizing the findings from one study to another. It is worth noting that because the nature of both online education and face-to-face contexts is different, each scenario requires specific guidelines and indications for teaching and learning purposes. Therefore, it would not be suitable to replicate online educational practices in this new mode of learning (traditional universities that have been forced to switch to remote learning). The evidence that confirms the particularities of each environment includes the following. A majority of educators from traditional universities do not have specialized training in the area of online or distance education. Thus, the ideal is to avoid situations like those experienced recently in which traditional classroom teaching methods have been integrated into online deliveries. Regarding the instructor profile, it is worth paying attention to the instructors’ adaptability not only because of uncertainty about new possible infectious diseases in the future but also for the evolution of instructors’ competencies in the era of online teaching and learning. In addition, there is a need to consider whether online programs have also undergone a change with regard to the students’ profiles. As demonstrated in the literature, a small percentage of students in online contexts are learners with no family or work commitments, whereas a majority of students need to balance their studies with other responsibilities [

50]. However, after the COVID-19 pandemic’s staggering impact on global higher education, attention should be paid to the potential of remote modes and digital scenarios, especially among young students. In this vein, rethinking the integration of life skills education from the early stages of higher education should be a necessity to prepare both young and adult students for this rapidly changing world. These are some of the reasons why, in this study, we support the idea of increasing research in the field of traditional education, especially in the era after COVID-19.